Abstract

Objective

To assess the preparedness status of a hospital in Beijing, China for implementation of an e-Health system in the context of a pandemic response.

Design

This research project used qualitative methods and involved two phases: (1) group interviews were conducted with key stakeholders to examine how the surveillance system worked with information and communication technology (ICT) support in Beijing, the results of which provided background information for a case study at the second phase and (2) individual interviews were conducted in order to gather a rich data set in relation to e-Health preparedness at the selected hospital.

Setting

In phase 1, group interviews were conducted at Centres for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) in Beijing. In phase 2, individual interviews were performed at a secondary hospital selected for the case study.

Participants

In phase 1, three group interviews were undertaken with 12 key stakeholders (public health/medical practitioners from the Beijing city CDC, two district CDCs and a tertiary hospital) who were involved in the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic response in Beijing. In phase 2, individual interviews were conducted with 23 participants (including physicians across medical departments, an IT manager and a general administrative officer).

Primary and secondary measures

For the case study, five areas were examined to assess the hospital's preparedness for implementation of an e-Health system in the context of a pandemic response: (1) motivational forces for change; (2) healthcare providers’ exposure to e-Health; (3) technological preparedness; (4) organisational non-technical ability to support a clinical ICT innovation and (5) sociocultural issues at the organisation in association with e-Health implementation and a pandemic response.

Results

This article reports a small subset of the case study results from which major issues were identified under three main themes in relation to the hospital's preparedness. These issues include a poor sharing of patient health records, prescription errors, unavailability of software tools to assist physicians in answering patient questions, physicians’ concerns about the reliability of ICT and the high monetary cost of e-health implementation and uncertainty over return on investment, and their dissatisfaction with the software in use.

Conclusions

Prior to the implementation of e-Health, planning must be undertaken to ensure the smooth introduction of the system. The assessment of organisational preparedness is an important step in this planning process. On the basis of a case study, deficient areas of organisational preparedness were identified for the prospective implementation of electronic health records. Accordingly, we suggested possible solutions for the areas in need of improvement to facilitate e-Health implementation's success.

Keywords: HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Article summary.

Article focus

How to assess organisational preparedness for the implementation of an e-Health system in the context of a pandemic response?

What is the preparedness status at a hospital in Beijing for the implementation of an e-health records system?

How did the surveillance system work with information and communication technology support in the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic response in Beijing?

Key messages

The occurrence of a pandemic can place an immense burden upon healthcare services, and e-Health systems may facilitate the functioning of healthcare facilities. The implementation of any information system in an organisational context requires proper planning and management for change. Prior to the implementation of e-Health systems, the assessment of organisational preparedness is an essential requirement.

There has been no work reported on the assessment of e-Health preparedness at healthcare facilities.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A part of our findings shows how IT applications were used in the functioning public health surveillance system in Beijing. This may provide decision makers at other settings with valuable insights to prepare themselves for a next pandemic from the surveillance perspective.

Our case study at a hospital in Beijing demonstrates how organisational preparedness can be assessed for the implementation of e-Health systems. Similar studies can be conducted in the future at various healthcare settings in countries to manage and plan the implementation of varied and specific e-Health systems.

Reported results from the case study may assist decision makers in the hospital to take action to address deficient areas in their preparedness and, as a result, facilitate the e-Health implementation's success.

The study results may be limited due to the participants’ over-reporting or their recall bias.

Another limitation is on the study design. This single-case study demonstrates the applicability of an integrated preparedness assessment framework that was developed and published recently. We understand that the evidence from multiple cases is often considered more compelling, and the overall study is therefore regarded as being more robust. However, the conduct of a multiple-case study requires extensive resources and time. For this project, we received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors; therefore, we selected a representative and typical case to achieve the study objectives.

Background

Influenza pandemics can occur with the appearance of a new strain of an influenza A virus against which none of the population has any immunity.1 A severe pandemic has the potential to increase morbidity and mortality levels, and consequently to cause economic losses worldwide.2 e-Health is an application of information and communication technology (ICT) across the whole range of functions that affect health. It may mitigate the impact of a pandemic by enhancing surveillance and control (eg, rapid case reporting), and improving the performance of clinical practice (eg, efficient documentation).3 4

The implementation of e-Health systems represents a disruptive change in the healthcare workplace and requires proper planning and management.5 The change occurs not only due to the introduction of ICT infrastructure but also because the job design of interconnected health professionals should be re-engineered to effectively and efficiently accommodate the technology.6 Resistance to change can occur at the individual level as well as at the organisational level.7 e-Health preparedness assessment becomes an essential requirement prior to the implementation of e-Health.8 9 The assessment is to identify problems with the present clinical practice processes and activities, healthcare providers’ exposure to e-Health (eg, perceived e-Health benefits), and available resources and socioculture of organisations to support the clinical ICT innovation for a pandemic. Action taken subsequently that addresses deficient areas of preparedness would hopefully facilitate changes resulting from e-Health systems’ implementation.

Although there have been some preliminary attempts to develop a framework for e-Health preparedness assessment, there has been no work reported on a systematic study on the evaluation of e-Health preparedness for public health services. Recently, an integrated e-Health preparedness framework10 was developed from the perspectives of the healthcare organisation and providers. Then the authors validated it by contextual interviews with 20 domain experts: 10 with e-Health implementation practitioners and the rest with medical/public health practitioners, and no modifications have been made on the constructs. However, this framework has not yet been applied in real healthcare settings. As a research strategy, the case study is used in many situations to contribute to our knowledge of individual, group, organisational, social, political and related phenomena—it allows investigators to retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events.11 In light of the integrated framework, we conducted a case study at a healthcare organisation in Beijing, which aimed to test its applicability and assess the preparedness status for the implementation of an e-Health system in the context of a pandemic response.

Methods

This study used a qualitative research approach and involved two phases: (1) group interviews were conducted with key stakeholders involved in the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic response in Beijing to examine how the surveillance system worked with ICT support, which provided background information for the case study and (2) individual interviews at a selected hospital to gather a rich data set in relation to e-Health preparedness assessment. The Medical and Community Health Research Ethics Advisory Panel, the University of New South Wales and the Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) approved the study protocol.

Interview guide

Phase 1

It was found that there was limited information in the literature on interactions of stakeholders involved in public health surveillance activities and ICT applications for the purpose of surveillance in China. An interview guide was developed to examine areas such as (1) key stakeholders’ interaction during the 2009 pandemic response; (2) surveillance data collection and use and (3) dissemination of information from public health authorities and feedback mechanisms.

Phase 2

On the basis of an integrated e-Health preparedness framework presented in ref. 10 an interview guide was developed to examine the following areas: (1) motivational forces for change that reflect the evaluator's realisation of problems and healthcare providers’ dissatisfaction with present practices or circumstances for pandemic responses. Pandemic responses at the healthcare organisation require its participation in pandemic diseases surveillance and control (such as case reporting to the state or local public health unit) as well as in the performance of medical practices (such as diagnoses and prescriptions); (2) healthcare providers’ exposure to potential e-Health applications (engagement preparedness) including their perceived e-Health benefits for a pandemic response, fears and concerns over using prospective e-Health systems, and their willingness to make the initial investment of extra time for e-Health training; (3) technological preparedness that reflects the capacity of the available hardware, software, computer networks and internal IT support particularly for troubleshooting at the healthcare organisation, as well as the sufficiency of healthcare providers’ previous IT experience to support an ICT innovation for medical practices; (4) resource preparedness, that is, organisational non-technical ability to support a clinical ICT innovation, including the decision makers’ specific knowledge of the ICT implementation, supportive policies at the organisational level and sufficient funding to support the whole innovation process and (5) societal preparedness that deals with sociocultural issues at the organisation in association with e-Health implementation and a pandemic response. Communication links and partnerships need to be available within and across the organisation. Questions from the interview guide were generated to evaluate preparedness measures at the bottom level of the hierarchical framework.10 Here is an illustrative question: were there any problems with the performance of medical practices during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic? For example, were there errors in prescriptions at the hospital?

Sample and site selection

Phase 1

Purposive sampling was used to recruit individuals to participate in the group interviews. Stakeholders nominated by the Beijing city CDC were provided with an overview of the study and were invited to participate. Consent was implied, if the participant agreed to undertake the interview. No identifiable information was collected in the interview.

Phase 2

To select a hospital for the case study, the Beijing city CDC initially recommended a small list of hospitals as possible candidates. There were a number of criteria which the hospital had to meet in order to be eligible. These included the following: (1) the hospital must have been involved in the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic response and (2) the hospital must be planning to implement a new e-Health system that can facilitate future pandemic response. Then two investigators made face-to-face explanations to the administrative officers and IT personnel at these hospitals on the objective of the research project. One hospital located in Beijing was finally selected, as the hospital met the case selection criteria and the management also showed their willingness to participate and offer a context for the study.

Purposive sampling was employed since the interviews required the participants’ knowledge of the status quo at the hospital to reveal its motivational, engagement, technological, resource and societal preparedness for the prospective e-Health system implementation. Owing to the nature of the data collected, three groups of participants were involved, specifically: (1) clinicians who had experience in diagnosing and reporting cases of influenza A (H1N1) and who would be end-users of the e-Health system; (2) an IT manager who provided IT support services (eg, troubleshooting) during the H1N1 pandemic and who was familiar with the ICT infrastructure (eg, what were the information systems in use?) at the hospital and (3) the Chief Information Officer/person who was in charge of the planning and implementation of the e-Health system. We also set the following inclusion criteria: participants must have worked at the hospital for a minimum of 2 years, and were full-time or part-time staff (contract workers were not included).

At the selected site, three interviews were piloted with a representative of the members of the study population of interest. The purpose was to evaluate the interview guide, for example, its readability, relevance and difficulty in interpreting and answering the questions asked. The instrument was modified accordingly.

Data collection

The recruitment process ended once enough detailed insights were provided to reach a point of saturation with respect to the surveillance system in Beijing during the 2009 pandemic outbreak and the preparedness areas at the selected hospital.

Phase 1

In February 2010, three group interviews were conducted in Chinese by one investigator. The first interview involved two public health practitioners from the Beijing city CDC. The second and third interviews involved 10 public health/medical practitioners from the city CDC, two district CDCs and a tertiary hospital (eg, the director of a district CDC and a medical doctor from the hospital).

Phase 2

A total of 23 in-depth interviews were conducted in Chinese by three investigators at the selected hospital between October and December 2010, respectively, with the general administrative officer, an IT manager, five physicians from the Respiratory Medicine Department, the director and six physicians from the Paediatrics Clinic Department, the director and four physicians from the Internal Medicine Emergency Department, the director and two physicians from the Infectious Diseases Department and a health worker from the Public Health Department. The interview with the health worker aimed to better understand the hospital's public health responsibilities and professional relationships with the district and city CDCs.

Analysis

With the participants’ permission, all the interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim. The process for coding the data was conducted manually and consisted of a number of steps. One-quarter of the transcripts were randomly selected and coded independently by three investigators who are bilingual and fluent in both English and Chinese. Each idea was given a code in Chinese that represented the meaning of the text segment. As a part of this step, respondents’ own words were used whenever possible. Through discussions between the three investigators, a list of themes was developed inductively. An agreed framework was then applied by one of the three investigators to code the remnant of the transcripts and the themes were modified. On the basis of the themes finally identified, the results of the analysis were written in English and then discussed with the other two investigators to ensure the accuracy and lexical equivalence. Lastly, the manuscript was modified according to the other authors’ further comments and feedback.

Context

Surveillance system in Beijing

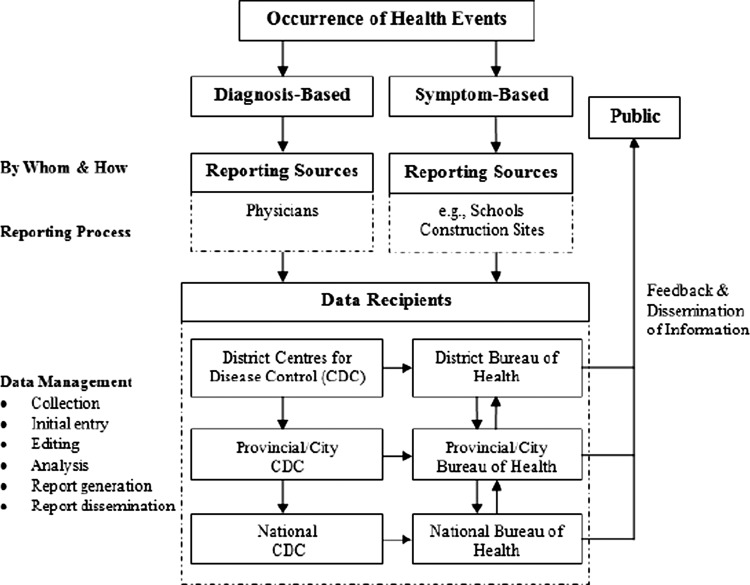

This section reports the key findings from the group interviews. When asked how the public health surveillance system worked during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic outbreak, all participants noted that various stakeholders participated in the surveillance activities in Beijing (including personnel from the national, provincial/city and district bureaus of health, CDCs at all levels, hospitals and schools) and ICT took an important role in facilitating the stakeholders’ interaction and communication. Figure 1 shows the stakeholders and their interactions for public health surveillance as part of the 2009 pandemic response.

Figure 1.

The major steps in the public health surveillance system in China.

When asked to explain in detail how notifiable diseases were normally reported, the participants indicated that it was initially performed by physicians either by filling out a paper-based form or through the electronic interface of an intranet website. A health worker from the hospital's public health department was usually designated to collect these forms in person once or twice a day or to retrieve that information in real time through the intranet website. The health worker was then required to check the completeness and legitimacy of the information reported by the physicians. Lastly, the health worker was responsible for importing the updated information into the CDC website. One participant believed that the completeness check improved the quality of case reporting and, as a result, benefited the prospective use and analysis of the surveillance data. During the pandemic, any data collected on the case reports were available in real time to the district CDCs through the CDC website.

After cases were reported to our district CDC, we were able to immediately capture the information using the website.

If a patient saw a doctor in District A but resided in District B, after the case was reported, both district CDCs could see the information in real time through the website.

As highlighted by some participants, these data could be shared by CDCs at all levels and health workers at the public health department of hospitals via the CDC website; nevertheless, they were not given the same level of accessibility.

Every district CDC could see the number of cases in the district but not that in other districts.

Chinese National CDC is able to see reports from all the cities/provinces whereas the reports seen by a district CDC are only a small subset.

Aside from the healthcare facility-based reporting, schoolteachers and construction site managers also share the responsibility of reporting cases on the basis of the person's symptoms (fever, diarrhoea, rash, jaundice or red conjunctiva). Many felt that the system of symptom-based reporting allowed control measures to be undertaken before the disease started to spread.

According to the participants, the surveillance data were analysed with ICT applications (eg, early aberration reporting system12) at all CDC levels; the analysis results were reported to the bureau of health at the same level. A public health practitioner explained that the analysis was undertaken to identify trends and affected populations, so that appropriate target groups were identified and control activities were implemented.

Hospital case study background

ICT has been applied at the hospital since 1999. At the initial stage, the application aimed to meet the hospital's financial needs. The manager of the IT department pointed out that in 2003 the hospital realised that the application should not merely focus on finance but should benefit clinical practices as well as decision-making processes at the management level. In the context of the 2009 pandemic outbreak, some interviewed physicians commented that they could proactively retrieve laboratory testing results through a laboratory information system once the results became available; they could also gain access to an intranet website and capture health alerts (eg, updated case definition) issued by public health authorities.

Since 2003, the hospital information system (HIS) for clinical practices has been replaced twice because neither of the first two suppliers was capable of upgrading their systems to meet the increasing clinical needs. The third HIS system had been implemented for both outpatient and inpatient services. The IT manager indicated that the second system for inpatient services was still in use and explained that it had kept all the information for inpatients who were already hospitalised before the implementation of the third system. The new system for outpatient services included a range of functions and mainly focused on the entry of medicine prescriptions and connections to the billing system. The general administrative officer pointed out that there was still a big gap regarding the retrieval of complete patient medical records for clinical decision making. Therefore, as the officer reported, the hospital had been planning to implement an electronic health records (EHR) system.

e-Health preparedness assessment results

On the basis of our discussions with 23 participants at the selected hospital and analysis of their responses, we assessed the hospital's preparedness for implementation of an EHR system in the context of a pandemic response. The preparedness issues were discussed within the five areas: (1) motivational forces for change; (2) healthcare providers’ exposure to e-Health; (3) technological preparedness; (4) organisational non-technical ability to support a clinical ICT innovation and (5) sociocultural issues at the organisation in association with EHR implementation and a pandemic response. Owing to the words limit, this section reports a small subset of the case study results from which major issues were identified in relation to the hospital's preparedness. These issues needed to be addressed prior to the implementation of EHR.

Explored area: motivational preparedness

Poor sharing of patient health records

Patient information required for clinical decision making was deemed by more than half of the interviewed physicians to be incomplete and inaccurate. Most physicians indicated that information could be partially obtained from the internal HIS, or from the paper-based patient medical history generated at the hospital or other healthcare facilities or, alternatively, by asking patients face-to-face during the physician–patient encounter. These physicians argued that patient information in the HIS mainly included past diagnoses and prescriptions at the hospital, whereas other information (eg, allergic history), which was also important for clinical decision making, was not saved. Furthermore, if those patients who had lost their medical card applied for a new card instead of renewing it, all information generated in the past would be no longer available. Although the paper-based patient medical history could provide extra evidence for clinical decision making, the utilisation of the information enclosed was another matter of concern. The director of the Infectious Disease Department provided an example of a patient with a medicine allergy: the diagnosing physician knew about it but still wrote down ‘no medicine allergy history’ in the medical history.

When I look at patient medical history generated by others, I cannot entirely trust it. (a senior physician, Department of Infectious Disease)

Inappropriate prescriptions

Physicians had utilised the HIS for prescriptions. A majority of physicians indicated that inappropriate prescriptions were caused by operational errors. A paediatrician provided an example in which, while she used an electronic interface to prescribe medicines for a patient, another patient whom she had already seen walked in with a laboratory test report; she switched over but used the interface to prescribe medicines for the wrong patient. A few commented that these mistakes sometimes happened especially when there were a large number of patients; nevertheless, they could be corrected in most cases when the patient went to the pharmacy with a different name on their prescriptions. Some physicians pointed out that inappropriate prescriptions could also be made in terms of medicine usage (eg, intravenous drip, injection or push) and dosage. Another physician added that due to the lack of updated information (eg, pregnancy) in relation to patients, medicines might have been prescribed to them despite there being contraindications.

Lack of assistance to answering patients’ questions

The majority of interviewed physicians indicated that they did not have access to the internet and nor were software tools available, at least as far as they knew, to search for information in relation to patients’ questions during their visits. Others argued that there was indeed an electronic pharmacopoeia and an intranet library to assist with answering some of the patients’ questions. One other physician commented that through the library they were able to find a small number of published papers or reports, but the quality of these was uncertain.

Explored area: engagement preparedness

Physicians’ concern about IT reliability

Most physicians believed that information technology was always reliable. Nevertheless, the majority of the physicians, including many of those who held a positive point of view, also clearly pointed out that information technology could be unreliable from time to time. They commented that: (1) there were pointless reminders when they prescribed medicines; (2) the HIS crashed sometimes and had to be rebooted, and as a result all work not yet saved needed to be redone; (3) the reliability of information stored in IT systems was another matter of concern. They argued that patient personal details (eg, residential address and contact number) might not be up to date; first-hand medical information collected from patients (eg, allergic history) might not be accurate or complete; the information in relation to past diagnoses and prescriptions saved in the HIS might not be correct and could be inappropriate in the first place; the information on medicinal drugs in the electronic pharmacopoeia might be out of date and (4) technical glitches in the HIS negatively impacted on physicians’ work efficiency.

Sometimes, after physicians generated and saved patient health records with the HIS for inpatient services, nothing was there. (a physician, Department of Internal Medicine Emergency)

Physicians’ concern about high investment and low reimbursement

For more than half of the interviewed physicians, high investment and/or low reimbursement were not their concern with using prospective e-Health systems. They argued that monetary investment was beyond their professional knowledge and there was nothing they could do about it. Some explained that decisions on the implementation of a new system were always made at the management level and that they had never been involved in that process at all. Regardless of the involvement in decision making, physicians’ medical practices (eg, work efficiency) would benefit in the long run, as a few noted.

However, the others indicated that the monetary investment on e-Health technologies had to be a matter of concern—physicians would pay for what they had been given (eg, from their bonus). They also commented that returns on the investment were dependent on the degree to which the technologies would be utilised to improve medical practices and patient care outcomes. When a large number of daily patient visits were taken into account, time which could be spent with every single patient was significantly limited and even less for the utilisation of technologies, and therefore returns on the investment could be unpredictable and appeared to be another matter of concern, as one physician emphasised.

Explored area: technological preparedness

The IT manager reported that all available ICT systems (eg, clinical and non-clinical software) at the hospital had formed a technical base for the implementation of any e-Health systems in the future. Many of the interviewed physicians were not only satisfied with the current software in use, but they also highlighted that the HIS needed to be upgraded in order to improve its performance (including technical errors and bugs, user-unfriendly interfaces, irrational operations and unmet requirements). One provided an example, explaining that as the buttons in the HIS used icons instead of captions (ie, text) to indicate what they do, it could take a while for end-users to remember them and become familiar with the operations.

The general administrative officer indicated that problems with the HIS encountered by physicians were being collated by the IT department, but that addressing these problems required a thorough analysis to check whether they could cause misalignments with the workflow defined at the hospital management level or with the requirements specified by the national Ministry of Health (eg, medical insurance policies).

Discussion

e-Health preparedness assessment helps the decision maker to be well-informed of deficient areas in preparedness, and therefore serves as a guide for preventive action to combat the failure to innovate.8 9 There is no study internationally on the evaluation of e-Health preparedness in an organisational context. In light of an integrated five-dimensional framework presented in ref. 10 a case study was conducted at a hospital in Beijing to assess organisational preparedness for the prospective implementation of an EHR system. This study has demonstrated its applicability in a real healthcare setting in China. Only major issues identified within three preparedness dimensions were reported in the previous section. Table 1 summarises these deficient areas of preparedness with possible solutions.

Table 1.

Deficient areas of preparedness at the hospital

| Areas of deficiency | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Sharing of patient health records | (a) Defining what information needs to be shared with whom and in which way |

| (b) With a prospective EHR system, ensuring that a variety of clinicians can not only access patient health information efficiently when required, but also ensuring that the information can be secured with patient privacy protected | |

| Appropriateness of prescriptions | Exploring options to decrease prescription errors such as automatic check of contraindication when electronic patient information is updated and complete |

| Availability of software tools to assist physicians in answering patient questions | Using a reference portal (eg, a clinical information website with a search engine) to create a filtered and customised set of contents |

| Clinicians’ concern about IT reliability and high investment and low reimbursement of the system implementation | (a) Making and executing education and awareness plans prior to the EHR implementation |

| (b) Improving clinicians’ understanding of how the EHR can benefit their performance in a pandemic situation and achieve better patient care outcomes | |

| Clinicians’ dissatisfaction with the software in use | Exploring ways to improve the human–computer interactional design to suit end-users such as involvement of clinical champions at the design phase |

EHR, electronic health records.

On the basis of assessment of motivational preparedness, identification of issues and challenges within present practices indicates the need for change.10 This information assists the hospital in defining its problems in relation to pandemic responses and in understanding how those problems can possibly be solved with innovations (eg, shared EHR systems).7 Unless motivation is ‘activated’, individuals within the organisation are unlikely to initiate change behaviours; perceived needs by healthcare providers impact on their behavioural intention to adopt and use an e-Health system (eg, refs. 13 and 14). Pandemic responses at the healthcare organisation require its participation in disease surveillance and control activities as well as in the performance of medical practices.10 In this study, possible issues particularly in relation to disease surveillance and control activities during the 2009 pandemic were not fully identified. The reason behind this could be that a wide range of e-Health applications were already set in place for the pandemic response. The case reporting process, for example, had been streamlined from diagnostic physicians to the internal public health department, and subsequently to the district CDC.

More serious issues were identified in medical practices including poor sharing of patient health records, prescription errors and unavailability of software tools to assist physicians in answering patient questions. Although the new HIS provides physicians with a function for prescription entry, inappropriate prescriptions can still be made due to system operation errors or the absence of updated patient information which is required for the consideration of contraindications. Therefore, some broad requirements for the EHR system that should be incorporated are to: (1) explore options to decrease prescription errors (eg, automatic check of contraindication when patient information is updated and complete); (2) ensure that a variety of clinicians can not only access patient health information efficiently when required, but also ensure that the information can be secured with patient privacy protected (further exploration is required for defining what information needs to be shared with whom and in which way) and (3) explore options to assist physicians in answering the patient's questions or seeking required clinical information (eg, a reference portal to create a filtered and customised set of contents15).

As part of the engagement preparedness assessment, interviewed physicians raised a couple of major concerns about using a potential EHR system. As healthcare providers are the key driving force in pushing e-Health initiatives, their concerns would impede further development of overall preparedness.10 First, their concern about the reliability of ICT was partially caused by their distrust in the information stored in IT systems. Their distrust may evoke anxious reactions when it comes to adopting new e-Health systems (eg, refs. 16 and 17). Second, interviewed physicians perceived a high monetary cost of e-Health implementation and uncertainty over return on monetary investment. This perception can inhibit their use of or intention to use e-Health (eg, refs. 18 and 19). If the increase in expenses outpaced that of compensation for the organisation, they would find it particularly hard to justify the risk in making any investment, especially in a new technology perceived as risky with uncertain returns (eg, the EHR).20 Healthcare providers’ perception of e-Health benefits determines the level of their fears and concerns.21 Therefore, to overcome these concerns, education and awareness plans need to be made and executed prior to the EHR implementation. These education programmes can improve the healthcare providers’ understanding of how the EHR can benefit their performance in a pandemic situation and achieve better patient care outcomes.

Under the technological preparedness dimension, physicians expressed their dissatisfaction with the software in use (particularly the newly implemented HIS) at the hospital, such as the user-unfriendly interfaces and irrational operations. Negative IT experience can cause them technology phobia and thus inhibit their adoption intention of a new e-Health system.22 23 With respect to the EHR system being planned, there is a need to explore ways to improve the human–computer interactional design to suit end-users (eg, involvement of clinical champions at the design phase).

The study results may be limited due to the participants’ over-reporting or their recall bias. In the case study, for example, the three groups of participants may have over-reported their preparedness in order to avoid embarrassment or judgement. We attempted to minimise bias in the interpretation of the interview data by having it reviewed by three investigators. It would be useful to have an independent bilingual person to ensure the accuracy and lexical equivalence of the data analysis results. As this study was undertaken as part of a PhD project, there was no funding available for this process. Furthermore, some questions in the interview guide required the participants to recall their past experiences; therefore, there may be some recall bias.

Conclusions

Pandemic preparedness planning is necessitated during the interpandemic period to enable countries to be prepared to recognise and manage an influenza pandemic.24 The first phase of this project contributes to a sharing of the surveillance experience in Beijing, especially with the other regions of China or countries where the public health surveillance system has been dysfunctional or not yet set up in place; some information drawn from this experience may help their preparation for a next pandemic from the surveillance perspective.

The project's second phase demonstrates the applicability of the integrated e-Health preparedness framework10 in a real healthcare setting. It also provides the medical informatics audience with an example of how e-Health preparedness assessment can be conducted in an organisational context. The case study results may assist decision makers at the hospital to take action to address deficient areas in their preparedness and, as a result, facilitate the EHR implementation success.

The integrated framework10 lays the foundation for e-Health preparedness assessment as illustrated here in the context of an influenza pandemic. However, the framework can be adapted to a range of clinical and public health environments. The applicability of the framework with these minor modifications would also require further studies. Similar case studies can be conducted at various healthcare settings (such as residential aged care facilities and primary healthcare centres) across countries to manage and plan the implementation of varied and specific e-Health systems such as EHR, e-learning, chronic illness management, telecardiology, teleradiology and teledermatology. These studies would engage staff members and seek their input to the specification of requirements for a clinical ICT innovation and also build organisational capacity for change.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JL was involved in (1) conception and design, acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting and revising the article and (3) final approval of the version to be published. HS was involved in (1) conception and design, and analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting and revising the article and (3) final approval of the version to be published. PR and RM were involved in (1) conception and design; (2) revising the article and (3) final approval of the version to be published. QW was involved in (1) acquisition of data; (2) revising the article and (3) final approval of the version to be published. PY and YZ were involved in (1) conception and design, and acquisition of data; (2) revising the article and (3) final approval of the version to be published. SL was involved in (1) acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data; (2) revising the article and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Medical and Community Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel, the University of New South Wales and Beijing Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This article reports a subset of the case study results from which major issues were identified in relation to the hospital's preparedness. Extra data are available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- 1.WHO Informal consultation on influenza pandemic preparedness in countries with limited resources. [Internet]: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/CDS_CSR_GIP_2004_1.pdf (accessed 7 May 2009)

- 2.WHO eHealth. [Internet] http://www.who.int/topics/ehealth/en/ (accessed 14 Jan 2010).

- 3.Li J, Moore N, Akter S, et al. mHealth for Influenza Pandemic Surveillance in Developing Countries. The 43 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), 5–8 January 2010, HI, USA.

- 4.Li J, Ray P. Applications of e-Health for Pandemic Management. IEEE 12th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Application & Services, 1–3 July 2010, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callioni P. Successful change management. [Internet]: www.ehealthexpo.com.au/content/view/59/45/ (accessed 15 Sep 2007).

- 6.Ford EW, Menachemi N, Phillips MT. Predicting the adoption of electronic health records by physicians: when will health care be paperless? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:106–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennett P, Yeo M, Pauls M, et al. Organizational readiness for telemedicine: implications for success and failure. J Telemed Telecare 2004;9(Suppl 2):S27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jennett P, Jackson A, Healy T, et al. A study of a rural community's readiness for telehealth. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:259–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demiris G, Oliver DRP, Porock D, et al. Home telehealth: The Missouri telehospice project: background and next steps. Home Health Care Technol Rep 2004;1:55–7 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li J, Ray P, Seale H, et al. An e-Health Readiness Assessment Framework for Public Health Services—Pandemic Perspective. The 45 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), 4–7 January 2012, HI, USA.

- 11.Yin RK. Case study research, design and methods. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centres for Disease Control (CDC) CDC Surveillance Update. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez Reynoso JM, Tulu B. Electronic medical records adoption challenges in Mexico. Chicago: AMIA Symposium Proceedings; 2007:1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiao SJ, Li YC, Chen YL, et al. Critical factors for the adoption of mobile nursing information systems in Taiwan: the nursing department administrators’ perspective. J Med Syst 2009;33:369–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ketchell DS, Anna LS, Kauff D, et al. PrimeAnswers: a practical interface for answering primary care questions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005;12:537–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennani A, Belalia M, Oumlil R. As a human factor, the attitude of healthcare practitioners is the primary step for the e-health: first outcome of an ongoing study in Morocco. Commun IBIMA 2008;3:28 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kifle M, Payton FC, Mbarika V, et al. Transfer and adoption of advanced information technology solutions in resource-poor environments: the case of telemedicine systems adoption in Ethiopia. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:327–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson JG. Social, ethical and legal barriers to e-health. Int J Med Inform 2007;76:480–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colpaert K, Van Belleghem S, Benoit D, et al. Has information technology finally been adopted in intensive care units? Intensive Care Med 2009;35:S235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bates DW. Physicians and ambulatory electronic health records. Health Aff 2005;24:1180–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boonstra A, Broekhuis M. Barriers to the acceptance of electronic medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy and interventions. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halamka J, Aranow M, Ascenzo C, et al. E-Prescribing Collaboration in Massachusetts: early experiences from regional prescribing projects. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:239–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemper AR, Uren RL, Clark SJ. Adoption of electronic health records in primary care pediatric practices. Pediatrics 2006;118:e20–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO WHO checklists for influenza pandemic preparedness planning. [Internet]. http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/influenza/FluCheck6web.pdf (accessed 3 Dec 2009)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.