Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association between self-rated health and risk of type 2 diabetes and whether the strength of this association is consistent across five European centres.

Design

Population-based prospective case-cohort study.

Setting

Enrolment took place between 1992 and 2000 in five European centres (Bilthoven, Cambridge, Heidelberg, Potsdam and Umeå).

Participants

Self-rated health was assessed by a baseline questionnaire in 3399 incident type 2 diabetic case participants and a centre-stratified subcohort of 4619 individuals from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-InterAct study which was drawn from a total cohort of 340 234 participants in the EPIC.

Primary outcome measure

Prentice-weighted Cox regression was used to estimate centre-specific HRs and 95% CIs for incident type 2 diabetes controlling for age, sex, centre, education, body mass index (BMI), smoking, alcohol consumption, energy intake, physical activity and hypertension. The centre-specific HRs were pooled across centres by random effects meta-analysis.

Results

Low self-rated health was associated with a higher hazard of type 2 diabetes after adjusting for age and sex (pooled HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.48 to 1.88). After additional adjustment for health-related variables including BMI, the association was attenuated but remained statistically significant (pooled HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.53). I2 index for heterogeneity across centres was 13.3% (p=0.33).

Conclusions

Low self-rated health was associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes. The association could be only partly explained by other health-related variables, of which obesity was the strongest. We found no indication of heterogeneity in the association between self-rated health and type 2 diabetes mellitus across the European centres.

Keywords: Diabetes & Endocrinology, Preventive Medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

Self-rated health (SRH) has been widely used as a global health measure. Several cross-sectional studies have suggested an association between low SRH and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

We aimed to prospectively investigate the association between SRH and risk of T2DM and whether the strength of this association is consistent across five European centres. A population-based case-cohort study design was used in the study.

Key messages

Results from this study provide some evidence that low SRH is associated with a higher risk of T2DM. The association could be only partly explained by other health-related variables, of which obesity was the strongest.

We found no indication of heterogeneity in the association between SRH and T2DM across centres.

Strength and limitations of this study

The study used a thorough ascertainment and verification of T2DM cases and included populations from four different European countries.

The assessment of SRH differed somewhat between centres regarding the construct (formulation, response alternatives and time frames) of the SRH question.

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) worldwide has more than doubled since 1980.1 In 2010, it was estimated that over 250 million people suffered from T2DM.2 Several risk factors have been identified (eg, age, body mass index (BMI), family history and physical inactivity), but the aetiology of T2DM is complex and still largely unknown. Self-rated health (SRH) is a subjective measure of health usually defined by responses to a single question such as ‘How do you rate your health?’ SRH is suggested to capture physical, psychological and social aspects that may be difficult to assess by objective health measurements.3 Furthermore, SRH has been associated with ‘bodily sensations and symptoms that can reflect disease in clinical or pre-clinical stages’.4 5 Individuals with poor SRH tend to have higher mortality,3 6 poorer physical activity (PA)7 and higher healthcare utilisation8 than individuals rating their health as excellent or good. It is likely that individuals with poor SRH face larger or different barriers to adopt a healthy lifestyle, which may be of relevance to how prevention efforts should be targeted. Several cross-sectional studies in different populations have reported associations between poor SRH and prevalent diabetes9–11 or glucometabolic disturbance.12 The primary aim of this study was to investigate the association between SRH and the risk of T2DM. As a secondary aim, we investigated whether the strength of this association was consistent across five European centres. A few previous prospective studies have evaluated the association between SRH and the incidence of T2DM. A study by Tapp et al13 showed that poorer SRH is associated with newly diagnosed T2DM after a 5-year follow-up, but the study was limited by high loss to follow-up. In a recent study, Latham and Peek14 found that SRH was a significant predictor for six major chronic diseases, including diabetes, among late midlife US adults. However, the outcome assessment in the study was based on self-reports, which makes the measurement susceptible to misclassification. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-InterAct Study is a large case-cohort study with thorough ascertainment and verification of T2DM that provides an ideal setting to investigate the association between SRH and T2DM across several European countries.

Methods

Study population

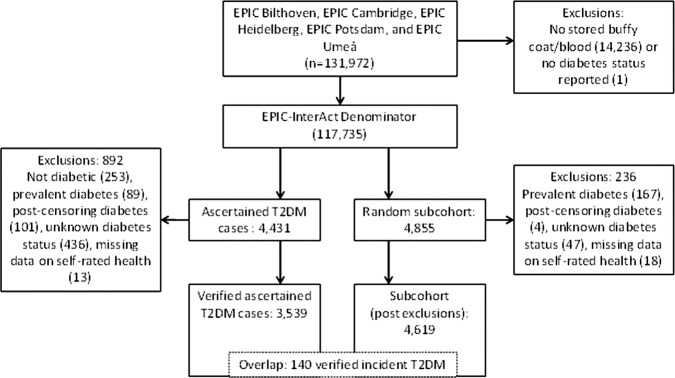

The InterAct Project was initiated to investigate how genetic and lifestyle behavioural factors, particularly diet and PA, interact on the risk of developing diabetes and how knowledge about such interactions may be translated into preventive action. The EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study was nested in the EPIC, which in total consists of 519 978 men and women across Europe.15 Out of these, 340 234 participants were eligible for the EPIC-InterAct study, which includes centres from eight different European countries (Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK). A detailed description of the study design and methods can be found elsewhere.16 In the present analysis, we only included centres that had baseline data available on SRH (Germany: Heidelberg and Potsdam; the UK: Cambridge; the Netherlands: Bilthoven; Sweden: Umeå). Participants were enrolled between 1992 and 2000. An overview of the five centres is presented in table 1. Among the participants from the five centres included in this study, 3 399 incident T2DM cases and a subcohort of 4 619 individuals remained after exclusions (figure 1). Owing to the random nature of the case-cohort design applied in the present study, the subcohort also included 140 individuals who developed T2DM during follow-up. All participants gave written consent and the study was approved by the ethical review board of the International Agency for Research on Cancer and by the local review boards of the participating centres.

Table 1.

Overview of the five centres included in the study from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-InterAct study

| Centre | Description of source population | Baseline collection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Women (%) | 5th and 95th age percentiles | ||

| Bilthoven | Participants were invited as an age-stratified and sex-stratified random sample of the general population | 22715 | 55 | 23–58 |

| Cambridge | Volunteers were invited as a random sample of the population listed at general practitioners | 30441 | 55 | 45–74 |

| Heidelberg | Volunteers were invited from the general population | 25540 | 53 | 37–63 |

| Potsdam | Volunteers were invited from the general population | 27548 | 60 | 36–64 |

| Umeå | Participants were invited as a random sample of the population | 25728 | 52 | 30–60 |

Figure 1.

Overview of the five centres included in the study from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-InterAct study.

Ascertainment of T2DM cases

Incident cases of T2DM until 31 December 2007 were ascertained and verified at each EPIC centre participating in the Epic-InterAct project using follow-up questionnaires (T2DM diagnosed by a medical doctor or antidiabetic drug use), linkage to primary and secondary care registers, medication use (prescription registers), hospital admission and mortality data and individual medical-record review at some centres. To increase the specificity of the case definition and to avoid inclusion in the study based on self-report of T2DM alone, further evidence was sought for all incident cases of T2DM. T2DM cases were included in the study only if confirmation of the diagnosis was secured from no less than two independent sources. Cases in Umeå were not ascertained by self-report, but identified via local and national diabetes and pharmaceutical registers, and hence all ascertained cases were considered to be verified.16

Assessment of SRH

SRH was assessed at baseline using self-administered questionnaires in the native language. The questionnaires were somewhat differently formulated at each centre and were therefore standardised (described in the appendix). Given the low frequency of responses in the extreme categories (n=305 in the lowest category), we dichotomised the SRH variable in the analysis by combining the two highest categories (high SRH) and the two lowest categories (low SRH) in order to increase statistical power. This is also in conformity with previous research.17–19

Assessment of covariates

Weight and height were measured with participants not wearing shoes. Each participant's body weight was corrected for clothing worn during measurement in order to reduce heterogeneity due to protocol differences among centres.20 BMI was calculated as weight (kilograms) divided by height (metres) squared. Hypertension was defined as self-reported medical history of hypertension or hypertension (based on measurements or drug use) at baseline. Further health-related variables were collected using questionnaires including questions on educational level, smoking status (current smoker vs non-smoker or exsmoker), diet, PA level, alcohol consumption and previous myocardial infarction. PA was assessed using the Cambridge index, a Validated rdered Categorical Global Index of activity derived from simple questions assessing recreational and occupational activity.21

Statistical analysis

The association between SRH and various baseline characteristics within the subcohort was tested using a χ2 test (for categorical variables) and a Kruskal-Wallis test (for continuous variables). Cox proportional hazards regression, modified for the case-cohort design according to the Prentice method,22 was used to estimate centre-specific HRs and 95% CI for the association between SRH and T2DM.

Age was used as the primary time variable, with entry time defined as the participant's age in years at recruitment and exit time as the participant's age in years at date of diagnosis, death or censoring. The centre-specific HRs were then pooled across centres by random effects meta-analysis.

It is not clear whether SRH mechanistically operates as an indicator of some unmeasured process or as a summary of a large number of other measures.3 23 Therefore, a large set of covariates were considered as potential confounders and included in models to determine pooled HRs at different levels of adjustment. All models were adjusted for age and sex. Each model was then further adjusted for the other health-related variables, one at a time, and finally, all potential confounders in the same model. Education level, smoking status, PA and hypertension were included as categorical variables, whereas BMI, alcohol consumption and energy intake were included as continuous variables. I2—the percentage of variation between centres due to heterogeneity—was calculated. A possible interaction between SRH and sex on T2DM incidence was tested by introducing an interaction term in the regression analysis. We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding participants who were diagnosed with T2DM within 2 years of follow-up. In a second sensitivity analysis, we excluded all participants with a history of myocardial infarction at baseline. To investigate the impact of excluding 323 T2DM cases and 405 members of the subcohort with missing data on covariates, a third sensitivity analysis was conducted by multiple imputation of missing data considered missing at random (based on 5, 10 and 50 imputations) in cases and non-cases. For each variable with missing data, a predictive model was created among participants with no missing data; that model was then used to predict values for participants who were missing those data.24 All analyses were performed using Stata V.11.2, except for the random effects meta-analysis, which was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V.2.

Results

The mean follow-up time was 9.1 years (±3.8). SRH by centre in incident cases of T2DM and subcohort individuals is presented in table 2. Table 3 shows the baseline characteristics of individuals in the subcohort by categories of SRH. Participants with low SRH were younger, had a lower educational level and a higher BMI than participants with high SRH. Moreover, participants with low SRH were more often smokers, less physically active, had lower alcohol consumption and estimated reported energy intake, and more frequently had hypertension and a history of myocardial infarction than persons with high SRH.

Table 2.

Self-rated health by centre in 3399 incident cases of type 2 diabetes mellitus and 4619 participants in the subcohort in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-InterAct study

| Centre | Self-rated health |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High |

Low |

|||

| Excellent | Good | Moderate | Poor | |

| Bilthoven | ||||

| Cases | 13 (4.3) | 184 (61.5) | 73 (24.4) | 29 (9.7) |

| Subcohort | 52 (9.0) | 403 (70.0) | 101 (17.5) | 21 (3.6) |

| Cambridge | ||||

| Cases | 92 (12.3) | 428 (57.1) | 206 (27.5) | 24 (3.2) |

| Subcohort | 159 (16.2) | 624 (63.4) | 170 (17.4) | 23 (2.3) |

| Heidelberg | ||||

| Cases | 173 (23.1) | 395 (52.8) | 156 (20.9) | 24 (3.2) |

| Subcohort | 286 (32.9) | 448 (51.5) | 125 (14.4) | 11 (1.3) |

| Potsdam | ||||

| Cases | 118 (15.2) | 460 (59.4) | 171 (22.1) | 26 (3.4) |

| Subcohort | 274 (23.1) | 721 (60.9) | 164 (13.9) | 25 (2.1) |

| Umeå | ||||

| Cases | 155 (18.7) | 369 (44.6) | 236 (28.5) | 67 (8.1) |

| Subcohort | 265 (26.2) | 477 (47.1) | 215 (21.2) | 55 (5.4) |

Data shown are numbers of individuals (percentage).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of subcohort individuals in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-InterAct study by categories of self-rated health

| Self-rated health |

p Value for overall difference* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High |

Low |

||||||||

| Excellent |

Good |

Moderate |

Poor |

||||||

| Mean/% | SD/N | Mean/% | SD/N | Mean/% | SD/N | Mean/% | SD/N | ||

| Age (years) | 48.8 | 10.3 | 50.5 | 11.1 | 51.7 | 10.9 | 50.3 | 10.2 | <0.001 |

| Sex (% men) | 42.8 | 443 | 45.2 | 1208 | 44.8 | 347 | 37.8 | 51 | 0.24 |

| Educational level (%) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Primary school or none | 19.2 | 194 | 24.4 | 635 | 37.9 | 287 | 30.8 | 40 | |

| Technical/professional school | 34.6 | 351 | 35.0 | 910 | 29.6 | 224 | 32.3 | 42 | |

| Secondary school | 14.9 | 151 | 14.2 | 369 | 14.4 | 109 | 18.5 | 24 | |

| Higher (incl. university degree) | 31.3 | 317 | 26.4 | 688 | 18.1 | 137 | 18.5 | 24 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 | 3.4 | 25.5 | 4.0 | 26.2 | 4.5 | 25.6 | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (%) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Never | 52.1 | 540 | 46.6 | 1246 | 41.7 | 323 | 40.7 | 55 | |

| Former | 27.5 | 285 | 30.1 | 804 | 30.1 | 233 | 23.7 | 32 | |

| Current | 18.8 | 195 | 21.0 | 561 | 26.1 | 202 | 32.6 | 44 | |

| Unknown | 1.5 | 16 | 2.3 | 62 | 2.2 | 17 | 3.0 | 4 | |

| Physical activity (%) | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Inactive | 15.9 | 160 | 21.3 | 548 | 31.1 | 231 | 43.3 | 52 | |

| Moderately inactive | 33.2 | 335 | 31.7 | 818 | 28.8 | 214 | 29.2 | 35 | |

| Moderately active | 25.5 | 257 | 26.8 | 689 | 21.8 | 162 | 15.0 | 18 | |

| Active | 25.5 | 257 | 20.2 | 521 | 18.2 | 135 | 12.5 | 15 | |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | 11.5 | 16.2 | 10.8 | 15.2 | 9.2 | 15.4 | 5.6 | 9.8 | <0.001 |

| Total energy intake (kcal) | 2016.6 | 649.7 | 2056.7 | 618.3 | 2009.4 | 617.3 | 1928.3 | 617.9 | 0.007 |

| Hypertension (%) | 16.0 | 165 | 22.8 | 600 | 32.7 | 245 | 33.3 | 44 | <0.001 |

| History of myocardial infarction (%) | 0.4 | 4 | 1.5 | 40 | 3.6 | 28 | 3.7 | 5 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean and SD for continuous variables and percentages and frequencies for categorical variables.

*Comparing excellent, good, moderate and poor self-rated health.

BMI, body mass index.

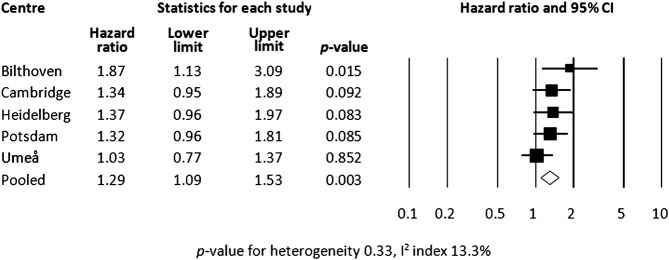

In a model with adjustment for age and centre, low SRH was associated with a higher hazard of T2DM (HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.48 to 1.88; table 4). We found no significant interaction between SRH and sex on T2DM incidence (p=0.54) and the analyses were therefore not stratified by sex. The strength of the association between SRH and T2DM was mainly unaffected by adjustment for smoking, alcohol consumption and estimated reported energy intake. Adjustment for other health-related variables, BMI in particular, led to attenuation of the association (adding BMI to the model attenuated the pooled HR to 1.38, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.60). In a final model with adjustment for age, sex, education, BMI, smoking, PA, alcohol consumption, estimated reported energy intake and hypertension, the association was attenuated but remained significant (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.53). The centre-specific HRs and the pooled HR, based on the final model, are presented in figure 2. We found no indication of heterogeneity in the association between SRH and T2DM across centres (I2 index 13.3%, p=0.33).

Table 4.

Pooled HRs of incident T2DM comparing low (moderate or poor) versus high (excellent or good) self-related health

| High self-rated health | Low self-rated health | |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled HR (95% CI) | Pooled HR (95% CI)* | |

| Model 1: Adjusted for age and sex | 1.00 (referent) | 1.67 (1.48 to 1.88) |

| Model 1+education | 1.00 (referent) | 1.60 (1.42 to 1.81) |

| Model 1+BMI | 1.00 (referent) | 1.38 (1.19 to 1.60) |

| Model 1+smoking | 1.00 (referent) | 1.67 (1.48 to 1.89) |

| Model 1+physical activity | 1.00 (referent) | 1.59 (1.41 to 1.80) |

| Model 1+alcohol consumption | 1.00 (referent) | 1.67 (1.48 to 1.89) |

| Model 1+energy intake | 1.00 (referent) | 1.67 (1.48 to 1.88) |

| Model 1+hypertension | 1.00 (referent) | 1.48 (1.31 to 1.69) |

| Model 1+all covariates above | 1.00 (referent) | 1.29 (1.09 to 1.53) |

*Pooled HRs calculated using a centre-stratified approach in combination with a random-effect meta-analysis.

BMI, body mass index; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

Centre-specific and pooled HRs of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus adjusted for the variables in the final model (age, sex, education, body mass index, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, energy intake and hypertension).

In a first sensitivity analysis, we excluded participants who were diagnosed with T2DM within 2 years of follow-up (n=398). These exclusions had only a minor effect on the pooled HR (1.29, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.55, adjusted for the variables in the final model). The number of participants with a history of myocardial infarction was low (n=202) and the multivariate model did not fit when this covariate was included. Thus, in the second sensitivity analysis, we excluded all participants with a history of myocardial infarction at baseline. This did not change the conclusions (pooled HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.50, adjusted for the variables in the final model). Owing to missing data on covariates, 323 T2DM cases and 405 members of the subcohort were excluded from the analyses. As a third sensitivity analysis, multiple imputations of these data, assuming missingness at random, were conducted. No significant differences in results were found in datasets based on 5, 10 or 50 imputations, compared with the original dataset. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the results are biased due to missing data.

Discussion

In this prospective case-cohort study, we found that low SRH was associated with a higher risk of T2DM. The association was partly explained by other health-related variables, particularly BMI. A somewhat unexpected finding was that the association between SRH and T2DM was mainly unaffected by adjustment for smoking, alcohol consumption and estimated reported energy intake. We found no indication of heterogeneity in the association between SRH and T2DM across the European centres.

SRH has been widely used as a global health measure. Previous studies on general populations have shown that there is a strong relationship between SRH and mortality, even after controlling for sociodemographic factors, objective measures of health status and health behaviours.6 25 A few studies have investigated the association between SRH and mortality in populations of diabetes patients with results similar to those of general populations.18 26 27 SRH and prevalent diabetes have been associated in several cross-sectional studies.9–12 28 However, cross-sectional studies are limited by their inability to study the temporal sequence of exposure and disease. Furthermore, these studies have not separated types 2 and 1 diabetes.

Any causality cannot be established by an observational study, but the findings in this prospective study imply that there is a dominant direction of this association from low SRH to T2DM (ie, a temporal relationship). We have found only two previous prospective studies showing the association between SRH and T2DM in large general populations. In the Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle study, Tapp et al13 found that participants with newly diagnosed diabetes had reported impaired general health before the onset of T2DM. The study was limited by a shorter follow-up (5 years) and did not present any sensitivity analysis excluding participants, who were diagnosed with T2DM shortly after baseline, which makes a bidirectional association more likely. In our study, with a mean follow-up of over 9 years, the association between SRH and T2DM remained when we excluded participants who were diagnosed with T2DM within 2 years of follow-up. Recently, Latham and Peek14 published a report from the Health and Retirement Study, a longitudinal survey of a US midlife cohort. They found that SRH predicted diabetes as well as coronary heart disease, stroke, lung disease and arthritis but not cancer. A weakness in the study was that the outcome measurement was based on self-reports. Our study supports this previous prospective research by also showing an association between SRH and T2DM when a strict verification procedure for outcome measurement is applied.

In the present study, low SRH was associated with a higher BMI, which is in line with previous research. In a study investigating the relationship between SRH and obesity, Prosper et al found that obese individuals had threefold greater odds of reporting reduced health compared with individuals with normal weight or overweight. As obesity is also considered to be a major risk factor for diabetes,29 it is likely to explain a substantial part of the association between low SRH and T2DM. Thus, it is not surprising that BMI may act as an important confounder in the association between SRH and T2DM in this study—or as a mediator since SRH and obesity might be on the same causal pathway. More surprising was the fact that participants with low SRH had lower alcohol consumption and estimated reported energy intake. These findings are not easily explained and raise questions regarding the criteria for self-assessment. Previous research on occupational cohorts has suggested that SRH principally reflects physical and mental health problems and, to a lesser extent, age, early life factors, family history, sociodemographic variables, psychosocial factors and health behaviours.23 One study that used in-depth interviews found that the same frame of reference is not used by all respondents in answering this question.30 Some study participants think about specific health problems when asked to rate their health, whereas others think in terms of either general physical functioning or health behaviours. In our study, the question for SRH referred to different time frames (eg, satisfaction with health today in Germany and perception of health over the last year in Sweden). SRH has been shown to be stable over time in population-based studies, suggesting that a considerable component of SRH reflects an aspect of one's enduring self-concept and, to a lesser extent, a spontaneous assessment of one's health status.31 Thus, the impact of different time frames on SRH assessment is likely to be small.

Compared with studies of SRH with mortality outcomes in individuals with diabetes,18 26 27 the strength of the SRH association (with T2DM incidence) found in the present study was weak. There may be several explanations for this. It has been shown that diabetes patients have higher death rates from several causes,32 including cancer.33 It is likely that the comparatively strong association between SRH and mortality is due to the higher ability of SRH to summarise global health risk among diabetes patients than specifically metabolic risk in a general population. It is also possible that SRH is more susceptible to ‘reporting behaviour’ (ie, how optimistic or pessimistic people are about their health)34 in a generally healthier population compared with subjective health ratings later on in the disease process.

Previous findings suggest that there may be sex differences in the SRH-mortality association,35 but we found no sex difference in the association between SRH and T2DM. SRH may also vary across countries.36 In the present study, it is likely that the differences in SRH across centres can, to some extent, be explained by different sampling strategies and age distributions at different centres. We did not find support for heterogeneity in the association between SRH and T2DM across centres in this study. However, the study was restricted to countries in northern Europe. It is, therefore, not clear how these findings are generalisable to other populations. Moreover, in Heidelberg and Potsdam, the SRH question was assessed in terms of satisfaction with health and in the other centres in terms of perception of health, which may have had an influence on the distribution of responses. There were also some differences in response alternatives between centres. To some extent, these differences were handled by standardisation, but the differences in the construct of the SRH question between centres are limitations to this study, particularly to the analysis of heterogeneity.

The strengths of the present study include the thorough ascertainment and verification of T2DM cases. Moreover, cultural differences may also have an impact on SRH, even within Europe, and we included populations from four different European countries.37 Several limitations of the study have already been listed, such as different constructs of the SRH question and the restriction to countries in northern Europe. We would also like to point out that it is possible that participants reporting low SRH at baseline were more likely to seek medical advice during follow-up and hence were more likely to be tested for diabetes (detection bias). If this was the case, the study may have overestimated the risk of T2DM associated with low SRH.

In our study, part of the SRH-T2DM association seemed to be explained by medical history as well as lifestyle variables. SRH may therefore be considered as a summary health measure—also for metabolic health. If there is access to several of the established risk factors for diabetes, SRH is not likely to add more than marginally to risk prediction on top of the conventional risk factors. However, whether SRH adds predictive value over and above established risk factors needs to be further analysed using adequate methods.38

In conclusion, results from this prospective case-cohort study provide some evidence that low SRH is associated with a higher risk of T2DM. The association could be only partly explained by other health-related variables, of which obesity was the strongest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all EPIC participants and staff for their contribution to the study. We also thank Nicola Kerrison (MRC Epidemiology Unit, Cambridge) for managing the data for the InterAct Project.

Footnotes

Contributors: OR and PW conceived the idea of the study. PW analysed the data and produced the tables and graphs. OR, SJS, CL, NF and NW provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by PW and OR and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. All authors contributed to either EPIC or EPIC-InterAct data collection, study management or coordination. All authors contributed to the interpretation and review of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding: Funding for the InterAct project was provided by the EU FP6 programme (grant number Integrated Project LSHM_CT_2006_037197). In addition, InterAct investigators acknowledge funding from the following agencies: DLvdA and AMWS: Dutch Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), Statistics Netherlands (The Netherlands); RK: Deutsche Krebshilfe.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the IARC Institutional Review Board and by the local review boards of the participating centres.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet 2011;378:31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:4–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benyamini Y. Why does self-rated health predict mortality? An update on current knowledge and a research agenda for psychologists. Psychol Health 2011;26:1407–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halford C, Anderzen I, Arnetz B. Endocrine measures of stress and self-rated health: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res 2003;55:317–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, et al. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mavaddat N, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, et al. What determines Self-Rated Health (SRH)? A cross-sectional study of SF-36 health domains in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:800–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSalvo KB, Jones TM, Peabody J, et al. Health care expenditure prediction with a single item, self-rated health measure. Med Care 2009;47:440–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramkumar A, Quah JL, Wong T, et al. Self-rated health, associated factors and diseases: a community-based cross-sectional study of Singaporean adults aged 40 years and above. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2009;38:606–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shadbolt B. Some correlates of self-rated health for Australian women. Am J Public Health 1997;87:951–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manor O, Matthews S, Power C. Self-rated health and limiting longstanding illness: inter-relationships with morbidity in early adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:600–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leosdottir M, Willenheimer R, Persson M, et al. The association between glucometabolic disturbances, traditional cardiovascular risk factors and self-rated health by age and gender: a cross-sectional analysis within the Malmo Preventive Project. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2011;10:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tapp RJ, O'Neil A, Shaw JE, et al. Is there a link between components of health-related functioning and incident impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes? The Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab) study. Diabetes Care 2010;33:757–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latham K, Peek CW. Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife US adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2013;68:107–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr 2002;5(6B):1113–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langenberg C, Sharp S, Forouhi NG, et al. Design and cohort description of the InterAct project: an examination of the interaction of genetic and lifestyle factors on the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the EPIC Study. Diabetologia 2011;54:2272–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker JD, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB, et al. Does self-rated health predict survival in older persons with cognitive impairment? J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1895–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEwen LN, Kim C, Haan MN, et al. Are health-related quality-of-life and self-rated health associated with mortality? Insights from Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD). Prim Care Diabetes 2009;3:37–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SJ, Moody-Ayers SY, Landefeld CS, et al. The relationship between self-rated health and mortality in older black and white Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1624–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, et al. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2105–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The InterAct Consortium. Validity of a short questionnaire to assess physical activity in 10 European countries. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:15–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, et al. Analysis of case-cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:1165–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh-Manoux A, Martikainen P, Ferrie J, et al. What does self rated health measure? Results from the British Whitehall II and French Gazel cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:364–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenward MG, Carpenter J. Multiple imputation: current perspectives. Stat Methods Med Res 2007;16:199–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamins MR, Hummer RA, Eberstein IW, et al. Self-reported health and adult mortality risk: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wennberg P, Rolandsson O, Jerden L, et al. Self-rated health and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasbach EJ, Klein R, Klein BE, et al. Self-rated health and mortality in people with diabetes. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1775–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prosper MH, Moczulski VL, Qureshi A. Obesity as a predictor of self-rated health. Am J Health Behav 2009;33:319–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haffner SM. Relationship of metabolic risk factors and development of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(Suppl 3):121S–7S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krause NM, Jay GM. What do global self-rated health items measure? Med Care 1994;32:930–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailis DS, Segall A, Chipperfield JG. Two views of self-rated general health status. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:203–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregg EW, Gu Q, Cheng YJ, et al. Mortality trends in men and women with diabetes, 1971 to 2000. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:149–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, et al. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009;16:1103–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Layes A, Asada Y, Kepart G. Whiners and deniers—what does self-rated health measure? Soc Sci Med 2012;79:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benyamini Y, Blumstein T, Lusky A, et al. Gender differences in the self-rated health-mortality association: is it poor self-rated health that predicts mortality or excellent self-rated health that predicts survival? Gerontologist 2003;43:396–405; discussion 372–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vadla D, Bozikov J, Akerstrom B, et al. Differences in healthcare service utilisation in elderly, registered in eight districts of five European countries. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:272–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jylha M, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Is self-rated health comparable across cultures and genders? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998;53:S144–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr, D'Agostino RB, et al. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72; discussion 207–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.