Abstract

Objectives

To investigate general practitioners’ (GPs) experiences in managing patients with intellectual disabilities (ID) and mental and behavioural problems (MBP).

Design

Qualitative study using in-depth interviews.

Setting

General practice in Hedmark county, Norway.

Participants

10 GPs were qualitatively interviewed about their professional experience regarding patients with ID and MBP. Data were analysed by all authors using systematic text condensation.

Results

The participants’ knowledge was primarily experience-based and collaboration with specialists seemed to be individual rather than systemic. The GPs provided divergent attitudes to referral, treatment, collaboration, regular health checks and home visits.

Conclusions

GPs are in a position to provide evidence-based and individual treatment for both psychological and somatic problems among patients with ID. However, they do not appear to be making use of evidence-based treatment decisions. The GPs feel that they are left alone in decision-making, and find it difficult to find trustworthy collaborative partners. The findings in this study provide useful information for further research in the field.

Keywords: Intellectual disability, General practice, Mental Health, Challenging behaviour, Qualitative Research

Article summary.

Article focus

The aim of this study was to investigate the general practitioners’ (GPs) experiences in managing people with intellectual disabilities and mental and behavioural problems (MBP) in order to identify factors related to high-quality services, important areas for improvement and suggest fields for further exploration.

Key messages

This study shows that GPs have different opinions on central subjects in providing high-quality services to people with ID and MBP.

Even GPs with an assumed high competence and engagement in this patient group lack evidence-based knowledge and base their actions on experience-based practice.

GPs are concerned about the competence in specialist departments when it comes to treatment of MBP in people with ID.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Participants were of both genders, from several localities and had a broad range of patients with ID and MBP.

As far as we know, this is the only study that has addressed GPs’ experiences with people with ID and MBP.

Although data across participants were found to be sufficient, a small group of participants were interviewed.

Introduction

People with intellectual disabilities (ID) are particularly vulnerable to health problems and experience difficulties in meeting their healthcare needs.1–7 Two recent attempts provide a focus to this challenge: a consensus manifesto by the European Association of Intellectual Disability Medicine8 and an independent inquiry on a request from the British Secretary of State for Health.9 These reports share the goal of improving healthcare services for people with ID, but the extent to which their recommendations have been implemented remains dubious. Similarly, guidelines have been developed in other countries.10–12 Courses are also available: for instance, in Norway, an internet course from the Norwegian Medical Association,13 and internationally, a course from the International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.14 It is, however, not clear how widely such training programmes for GPs are used.

A recent meta-analysis has shown that the prevalence of ID is approximately 1%.15 The prevalence of mental health problems among people with ID varies in different studies from 14% to 60% and can be difficult to identify and diagnose.16 There is considerable overlap between mental health problems and challenging behaviour17 18; these two complications are often inseparable, suggesting that there is little to gain from distinguishing between them when trying to identify implications for health workers. To detect and treat people with ID and mental and behavioural problems (MBP) is a test of the competence of the general practitioner (GP). Doctors specialising in general practice acquire knowledge about the early and general presentation of diseases, and the early treatment and follow-up of chronic disease. GPs play a central role because of their familiarity with other primary healthcare services, as gatekeepers to specialist healthcare and in evaluating treatment and cooperating with the patient, family and other service providers.19–22

Each Norwegian GP has 5–10 patients with ID on their list. Some of these patients will have MBP, which potentially influence their physical health, including poor diet; erratic compliance with medication and behaviour that can affect physical health, creating the need for close care and structure in health services.23 A qualitative study has identified areas of discomfort when it comes to proper educational training for GPs, to meet the health needs of people with ID.24 Results from another qualitative study with participants with ID showed that the participants wanted GPs with ability to listen with interest, take the patient seriously and take the time to explain and demonstrate medical investigations.7 GPs’ attitudes towards people with ID were investigated in a study. Although GPs held positive attitudes to managing ID patients, they were not so willing to give more time in consultation.25

The importance of closely monitored care and high-quality health services to meet the challenge of inequality in health services for people with ID has provided the focus for several papers.1 3 5 6 26 There are, however, few studies that have looked at the way GPs are working with patients with ID and MBP. The aim of our research was to explore the experiences, attitudes and perceived role and competence of GPs providing health services to patients with ID, with a special focus on patients with ID and MBP.

Methods

A qualitative method

We opted for a qualitative approach, in order to obtain more detailed descriptions of the GPs’ experiences serving patients with ID and MBP. In-depth interviews are suitable in inquiring about the GPs’ experiences, facilitating a deeper understanding of their opinions and attitudes.27 28 We preferred open interviews to focus on each participant's descriptions and experiences, and to bring narratives into the method, by giving participants the opportunity to provide meaning to their responses.

Participants

Data were drawn from a total of 10 interviews with 10 participating GPs aged 41–64 (table 1). Participants were chosen following recommendations from an acknowledged senior psychiatrist with more than 30 years of experience with ID patients in collaboration with GPs in Hedmark county. There are 173 GPs in Hedmark, and the senior psychiatrist considered 25 of them to have more than the usual level of experience with ID patients and a relatively large number of ID patients on their list. A letter was sent to 15 of these GPs, purposefully selected with regard to geographical location and gender. Ten GPs were able to participate, three GPs refused to participate and two GPs did not respond. Participation in this study was voluntary, and each participant signed an informed consent form, and was informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time, without further explanation.

Table 1.

Participant number, age, gender, location, total number of patients, approximate number of ID patients and reported number of ID patients with psychiatric/behavioural challenge

| Participant number | Age | Gender | Location | Total number of patients | Approximate number of ID patients | Reported number of ID patients with psychiatric/behavioural challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | F | Rural | 950 | 6 | 2 |

| 2 | 61 | M | City | 1200 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 60 | M | Rural | 800 | 14 | 4 |

| 4 | 64 | M | City | 2500 | 20 | 10 |

| 5 | 60 | M | Rural | 750 | 15 | 6 |

| 6 | 61 | M | City | 1000 | 5 | ? |

| 7 | 60 | M | City | 1100 | 30 | 20 |

| 8 | 42 | F | Rural | 850 | 7 | 3 |

| 9 | 59 | M | Rural | 1000 | 12 | 6 |

| 10 | 41 | F | Rural | 1300 | 10 | 5 |

Participants’ number, age, gender, location, total number of patients, approximate number of patients with ID and reported number of ID patients with mental or behavioural problems.

F, female; ID, intellectual disabilities; M, male.

Setting

All 10 interviews were conducted in the GPs’ offices, located in Hedmark county, an agricultural county with small towns and a total population of approximately 1 90 000. The interviews lasted 41–81 min, with a mean of 57 min. Interviews were conducted from October to November 2011 and were audio recorded. All but one interview was conducted by two of the authors (TF and KK), and there was no former relationship between the participants and the interviewers. The interviews were planned, and the participants were prepared on the topic and had allocated time for the interview. The interview consisted of open-ended questions based on an interview guide with two main questions:

What are your experiences with ID patients who have additional mental health problems and/or a challenging behaviour?

What do you think is the GP's role for these patients?

The additional checklist was used to gather information that was otherwise missing or to provide greater depth or breadth to incomplete information. Follow-up questions were taken from a list of keywords: number of patients with ID on the GP's patient list, collaborative partners, regular health checks, specific training on the topic, perceived knowledge, knowledge of evidence-based literature on the topic and attitude towards psychotropic treatment of people with ID.

Analysis

The interviewers made field notes with the participants’ frequently used words, phrases and other statements requiring follow-up. Pauses, engagement, laughter and gestures were also noted, and the field notes were used in addition to the total transcripts. The 10 interviews generated approximately 119 pages of single-spaced text. Analysis of transcripts was conducted using systematic text condensation.27 29 30 TF read the transcripts several times to obtain a sense of the whole. The other authors independently read the transcripts and identified meaningful units, themes and subthemes, trying to capture the ‘essential expression’. These findings were discussed among the authors.

Results

During the interview, GPs described their experiences, consultations and collaboration with a variety of relatives and professionals. Case presentations included descriptions of ID patients with complex medical, psychiatric and behavioural challenges. GPs shared examples of the kind of challenges they were facing in managing these patients. It could be a patient with Down syndrome, psychiatric illness and difficult to control diabetes. Other patients could be aggressive both verbally and physically and not willing to participate in tests in a typical consultation at the doctor's office. Some of the patients lived alone with little community services, and were having a lifestyle with several potential harmful traits, like smoking, drinking alcohol or eating disorders, and limited cognitive resources to understand the consequences of their actions.

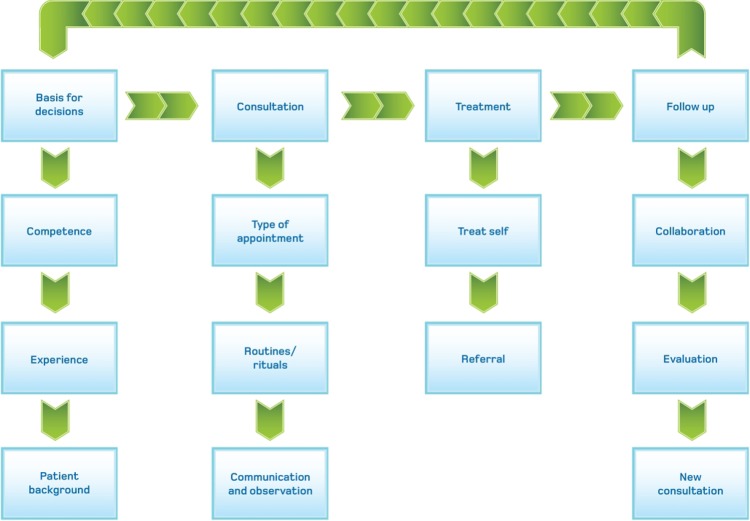

As a model of analysis, the process of a consultation emerged from the material as the best description of the GPs’ experiences with this group of patients (figure 1). This model illustrates a GP's pathway through a consultation with four main categories: basis for decisions, consultation, treatment and follow-up.

Figure 1.

Model with themes and subthemes.

Basis for decisions

The main category, basis for decisions, epitomises the GP's knowledge and experience in the context of the patient group and describes their medical education, experiences, courses and relevant postgraduate education on this topic. The GPs described limited training in patients with ID from their medical school or postgraduate courses. On direct question, none of the GPs had knowledge of The Medical Association’s internet-based course on the topic.

The Norwegian Medical Association arranges a lot of courses, but I have until today's date never seen a course on this topic. (GP #6)

When the GPs were directly asked on what basis they treated these patients, there was no mention of articles, books or peer-reviewed journals on the topic:

I think…those medications that I am used to prescribing, and that I know are effective in any or another way, I will use them as a common guideline. (GP #1)

I have common knowledge about patients and psychiatry. I have a large number of patients and I have years of experience. (GP #4)

It might be revealing, but I use common sense and my own experiences. (GP #9)

I haven't read any literature on this theme, but I have learned some in collaborating with Habilitation services. (GP #6)

Knowledge of the patients’ background and continuity in the relationship between patient and physician were seen as key issues in providing the best service. Furthermore, these GPs saw the advantage of being a family doctor, improving the relationship to the patients and allowing the GP to make a better job of evaluating the biological, psychological and social strengths of the patients. As one participant said:

The family will be a support system for the patient anyway, so l see this as a great advantage. (GP #6)

A patient of me, his sister and sister's child are my patients. His sister has been here, lying on the bench pregnant. He knows this, and we talk a little about it. It seems to make him more comfortable and familiar with the situation when he knows I am helping more of his family as well. I can measure his blood pressure and do blood samples, some thing he was not able to do at his former GP. (GP #1)

A key finding in this category is that most of the treatment is founded on experience-based knowledge. The material was rich in descriptions of patient histories, organisational system changes and historical events in the ID healthcare service, together with private memories from childhood or random meetings with people with ID. Because the experiences are individual, there were many different stories, opinions and points of view.

Already in primary school I went to a school where people with ID were integrated. Having contact with people with ID has never been strange or unfamiliar for me. (GP #8)

Consultation

The second main category, consultation, covers the type of consultation, communication and individual routines or rituals by either the GP or the patient. First, there are descriptions of various types of consultations which can occur in either the office or the patient's home: acute consultation, planned evaluations of treatment and prescriptions and health checks. The GPs varied in their opinions about the benefits and possibilities of seeing the patient at home, as quotes from these two doctors illustrate:

Home visits are soon to become a closed chapter in general practice, but with these patients I find it necessary to do home visits. Then I can see with my own eyes how things appear at home. (GP #5)

They need to be observed and… it is not always easy for a GP to be able to observe. A GP should stay in the office and be available for patients. (GP #4)

Furthermore, the GPs have different opinions about the benefits and possibilities of regular health checks for this patient group. Lack of standard guidelines opens the door for individual solutions and a variety of explanations. One participant highlighted this patient group as bad requesters of healthcare, requiring closer follow-up:

We may not be optimally good at this, but we try to do it once a year, and that is about were it ends. Some have a health problem that leads to more frequent consultations; in those cases a yearly health control is less important. But in general these are patients who don't tend to promote themselves. (GP #9)

There were descriptions of patients who went through special routines and rituals in their GP's office. It seemed to be important for the relationship between the GP and the patient that these routines be followed; the patient tended to be calmer, allowing the doctor to undertake the necessary investigations. As one participant said:

He is sitting here, takes a glass of water, sits down again and drinks some water. Sometimes I am able to check his blood pressure and do blood tests. He was not able to do that with his previous GP. (GP #1)

Communication and observation constitute another cluster of experiences in this category. Some of these patients are obviously anxious about a consultation, and all GPs said that their focus was on the patient, communicating directly with the ID patients, even though they were accompanied by others. If something could not be done because of unwillingness or restlessness, they did not push the patient, but booked another appointment in the near future.

Our participants argued that their patients should be accompanied by someone who knows the patient, their medical history and the reason for the consultation. Yet patients with communication problems were sometimes accompanied to the doctor's office by health workers with limited knowledge of the patient. Because GPs must rely on information from accompanying persons, they would sometimes send the patient home with a new appointment. As one participant said:

It is essential that we have confidence in the information we are given. And that it is not exaggerated, hyped or trivialized, but is a sober description that it is possible for me as a GP to navigate towards. (GP #7)

Some participants were more likely to use systematic consultations and follow-up, especially if the patient had chronic somatic problems. Nevertheless, the somatic problem, rather than the ID and MBP, constituted the main reason for systematic and frequent consultations.

Treatment

This third main category covers the choice the GP must make in trying to solve the patient's medical or mental health problem: to treat the patient or refer to a specialist. The participants expressed insecurity about how to treat and what to do with these patients. They described types and possibilities when they wanted to treat the patient themselves following these justifications: (1) lack of confidence that a specialist would do the best job with these patients or (2) they believed the referral would be refused by the specialists’ health services. This participant illustrates the lack of confidence in specialist services, and trust in own competence:

I have to call a random chief doctor at the local psychiatric institution, because that is what the habilitation services relies on… then I think I will do this better by myself. (GP #5)

There were descriptions of all types of treatment, including checks for somatic reasons for restlessness, behaviour modification, environmental actions and medical treatment. When the participants referred these patients to specialist health services for their MBP, it was mainly for diagnostic work or medication queries. It was more common for the GPs to mention the name of a specialist rather than a specialist department.

If I wanted to refer a patient with these problems, NN was the person. (GP #3)

NN2, a psychiatrist with long experience, is easy to turn to, because he provides good answers to my questions. (GP #8)

Some of the GPs interviewed had created a private system to ensure systematic follow-up: prescribing medication over the short term and developing exclusive lists with patient data and consultation frequency.

Evaluation and continuing treatment

This fourth main category constitutes a cluster of descriptions covering collaboration, evaluation of treatment effects and routines for follow-up consultations. The participants reported their experiences with collaborative partners—particularly how they evaluated the effects of psychotropic medication.

A patient with ID and MBP nearly always involves one or more collaborative partners. Interdisciplinary meetings were described as useful if the GPs had the opportunity to participate. The GPs were not sure if they were invited to all meetings, but had the impression that their attendance and competence were wanted. There were descriptions of meetings with parents, community mental health workers, psychiatrists, psychologists and nursing home employees, but they differed in type, in the frequency of the GPs’ attendance and in the priority they placed on them.

I try to attend every primary meeting with collaborative partners. (GP #9)

I am not often called in to primary meetings. I am, in a few cases, where medical issues are central. (GP #7)

The GPs that attended usually found meetings with collaborators useful, despite the fact that most of these meetings dealt with issues far from the GPs’ areas of expertise. Some described meetings in which specific parts were structured towards their attendance, and this was considered to lower the barriers of GP attendance. Even though the GPs met a group of several collaborators facing the challenges of a patient, they felt alone in issues regarding medical questions for patients with ID and MBP. The feeling of being left alone was mentioned by several participants, but one participant was particularly clear about it:

I feel really alone on this topic with these patients. I don't really know what to do. (GP #10)

The participants admitted facing challenges in evaluating the effects of psychotropic medication. Some argued for a systematic evaluation of and specific feedback on their patients’ behaviour by parents or healthcare workers, in order to assess the effect of medication:

I need observations and detailed feedback. There's no point in continuing a treatment if it isn't effective. Systematic feedback is the required way of working. (GP #7)

Others wanted a standard feedback sheet:

Then you can have a summary over a longer time perspective, rather than some random reports. But I don't know where to get these schemes. (GP #10)

As schemes or more objective feedback forms were not often provided, the participants were forced to rely upon normative assessments provided by accompanying health workers or parents.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The results in this study highlight the complexity of providing GP services to people with ID and MBP. The GPs interviewed in this study were strategically selected and were expected to have above-average engagement and competence with this patient group. Evidence-based medicine requires a combination of clinical expertise, best available external evidence and individual patient needs and choices.31 The competence of the participants in this study is generally experience-based on this topic and therefore characterised by individual opinions and ways of working. The participants described limited education on ID issues, and none could refer to any scientific article, book or report on this topic. Even though there has been a course directed to GPs on ID patients, with a subcategory on MBP, none of the participants had attended it. This study implies that GPs with more than the usual level of experience, and interest in patients with ID and MBP, rely on experience-based knowledge, and have limited knowledge of articles, guidelines, reports or books on this topic. The fact that the management of patients with ID and MBP is rarely taught in medical school and the only course available is an internet course may contribute to the understanding of limited evidence-based knowledge among the participants. In addition, our results imply that this topic is rarely mentioned in scientific papers or on conferences and courses with GP participation.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The participants in this study were strategically selected, thereby representing a relatively homogeneous group. This situation creates an obvious threat to external validity, and may limit the generalisation of our results. Nevertheless, the interviewees revealed diverse opinions and descriptions of their managing of ID patients with MBP, thereby strengthening our impression that this is an important research topic, albeit rarely investigated or highlighted in national or international settings. Everyone in our research group has read and analysed the transcripts and independently noted meaningful units. The group comprises researchers and clinicians from several areas, thereby limiting the threat of a subjective finding with idiosyncratic perspectives and limited objective value. Our findings can be transferred to clinical situations and can provide a good starting point for further research in the field.

Comparison with the existing literature

There is no hard evidence for the necessity and efficacy of using psychotropic medication for treating MBP in people with ID.11 32–34 The fact that none of the GPs interviewed could mention any scientific paper that addresses this problem supports the finding that this is an experience-based field, in which doctors rely on general competence valid for people without ID. This is a noteworthy result, especially given the assumption that 70% of psychotropic medication to this patient group is prescribed by the GP alone, without collaboration with a psychiatrist.35 36 Furthermore, the results are in line with findings from another qualitative study that addressed the educational needs of family physicians of people with ID, pointing out a need for modifications of their education.24 The GPs interviewed focused on communicating with the person with ID, giving them time to do their rituals, and the importance of building relations with the patients. People with ID have provided useful information in a qualitative study, focusing on the importance of practical issues like patience, demonstrations of medical investigations and communication with the patient, not the support person.7 These attributes of a good patient–doctor relation are also mentioned by patients with chronic problems without ID.37

Implications for future research and clinical practice

The results demonstrate a major challenge to the treatment of MBP in people with ID: none of the participants were sure how to treat these patients themselves, yet they were unsure where to refer their patients if they found the situation too complicated for primary healthcare treatment alone. They tended to distrust specialist health services. In some areas of the county, the GPs mentioned a local hospital psychiatrist, and other participants mentioned specific persons with whom they could collaborate. All in all, these statements serve to underline the importance of knowledge and information exchange between potential collaborative partners.

Our study shows that GPs’ management of patients with ID and MBP is primarily based upon experience-based knowledge—as told explicitly and as demonstrated through individual descriptions of management and treatment. The GPs’ opinions about working with ID patients is based on their own experience with this patient group, and with their general competence related to patients without ID. Attention should be focused on the ways in which medical training and postgraduate education can fill the competence gap, to ensure that this field becomes evidence-based rather than merely experience-based. Guidelines for GP management of people with ID, with a subcategory focusing on MBP, should be developed and disseminated in Norway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the GPs for their participation.

Footnotes

Contributors: TF contributed to the acquisition of data, transcription, analysis of data, drafting and critical revision of the article and approval of the final version. ORH, LJD and LL contributed to the design of the study, analysis of data, critical revision of the article and approval of the final version. KK participated in the interviews, analysis of data, critical revision of the article and approval of the final version.

Funding: This study was funded by the Norwegian Medical Association. The funding body had no involvement in the research process or in the writing of this article.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Norwegian regional committee for medical research approved this study, ethical approval number 10-2008 SI.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Balogh R, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Bourne L, et al. Organising health care services for persons with an intellectual disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(4):CD007492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter H, Lowe K, Houston H, et al. Previously unidentified morbidity in patients with intellectual disability. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:93–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felce D, Baxter H, Lowe K, et al. The impact of checking the health of adults with intellectual disabilities on primary care consultation rates, health promotion and contact with specialists. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2008;21:597–602 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwok H, Cheung PW. Co-morbidity of psychiatric disorder and medical illness in people with intellectual disabilities. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20:443–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straetmans JM, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HM, Schellevis FG, et al. Health problems of people with intellectual disabilities: the impact for general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:64–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HM, Walsh PN. Managing health problems in people with intellectual disabilities. BMJ 2008;337:a2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wullink M, Veldhuijzen W, Lantman-de Valk HM, et al. Doctor-patient communication with people with intellectual disability—a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholte FA. European manifesto: basic standards of healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities. Salud Publica Mex 2008;50(Suppl 2):s273–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michael J. Healthcare for all: report of the independent inquiry into access to healthcare for people with learning disabilities. London: Aldridge Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldor R, O'Brien JM. [Internet]. Primary care of the adult with intellectual disability (mental retardation). (cited 23 Jan 2013) http://www.uptodate.com/contents/2779 (accessed 5 Feb 2013)

- 11.Deb S, Kwok H, Bertelli M, et al. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry 2009;8:181–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan WF, Berg JM, Bradley E, et al. Primary care of adults with developmental disabilities: Canadian consensus guidelines. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:541–68 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Norwegian Medical Association [Internet] Allmennlegens møte med utviklingshemmede (In Norwegian). http://nettkurs.legeforeningen.no/course/view.php?id=47 (accessed 4 Jan 2013).

- 14.International Association for the Scientific Study of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities [Internet] https://www.iassid.org/ (accessed 5 Feb 2013).

- 15.Maulik PK, Mascarenhas MN, Mathers CD, et al. Prevalence of intellectual disability: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32:419–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerker BD, Owens PL, Zigler E, et al. Mental health disorders among individuals with mental retardation: challenges to accurate prevalence estimates. Public Health Rep 2004;119:409–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen D. The relationship between challenging behaviour and mental ill-health in people with intellectual disabilities: a review of current theories and evidence. J Intellect Disabil 2008;12:267–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden B, Gitlesen JP. The relationship between psychiatric symptomatology and motivation of challenging behaviour: a preliminary study. Res Dev Disabil 2008;29:408–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berardi D, Bortolotti B, Menchetti M, et al. Models of collaboration between general practice and mental health services in Italy. Eur J Psychiatry 2007;21:79–84 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredheim T, Danbolt LJ, Haavet OR, et al. Collaboration between general practitioners and mental health care professionals: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst 2011;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredheim T, Lien L, Danbolt LJ, et al. Experiences with general practitioners described by families of children with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younes N, Gasquet I, Gaudebout P, et al. General practitioners’ opinions on their practice in mental health and their collaboration with mental health professionals. BMC Fam Pract 2005;6:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassiotis A, Barron DA, Hall IS. Intellectual disability psychiatry: a practical handbook. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson J, Dreyfus D, Cerreto M, et al. ‘Sometimes I feel overwhelmed’: educational needs of family physicians caring for people with intellectual disability. Intellect Dev Disabil 2012;50:243–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill F, Stenfert KB, Rose J. General practitioners’ attitudes to patients who have learning disabilities. Psychol Med 2002;32:1445–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neville BG. Mental health services for people with learning disabilities. Medical needs are important too. BMJ 2001;322:302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet 2001;358:397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giorgi A. Phenomenology and psychological research: essays. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giorgi A. The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: a modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brylewski J, Duggan L. Antipsychotic medication for challenging behaviour in people with learning disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD000377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matson JL, Bamburg JW, Mayville EA, et al. Psychopharmacology and mental retardation: a 10 year review (1990–1999). Res Dev Disabil 2000;21:263–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tyrer P, Oliver-Africano PC, Ahmed Z, et al. Risperidone, haloperidol, and placebo in the treatment of aggressive challenging behaviour in patients with intellectual disability: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008;371:57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baasland G, Engedal K. Use of psychotropic medication among individuals with mental retardation. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2009;129:1751–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holden B, Gitlesen JP. Psychotropic medication in adults with mental retardation: prevalence, and prescription practices. Res Dev Disabil 2004;25:509–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell SM, Gately C, Gask L. Identifying the patient perspective of the quality of mental healthcare for common chronic problems: a qualitative study. Chronic Illn 2007;3:46–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.