Abstract

Objectives

Till date, mutations in the genes PAX3 and MITF have been described in Waardenburg syndrome (WS), which is clinically characterised by congenital hearing loss and pigmentation anomalies. Our study intended to determine the frequency of mutations and deletions in these genes, to assess the clinical phenotype in detail and to identify rational priorities for molecular genetic diagnostics procedures.

Design

Prospective analysis.

Patients

19 Caucasian patients with typical features of WS underwent stepwise investigation of PAX3 and MITF. When point mutations and small insertions/deletions were excluded by direct sequencing, copy number analysis by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification was performed to detect larger deletions and duplications. Clinical data and photographs were collected to facilitate genotype–phenotype analyses.

Setting

All analyses were performed in a large German laboratory specialised in genetic diagnostics.

Results

15 novel and 4 previously published heterozygous mutations in PAX3 and MITF were identified. Of these, six were large deletions or duplications that were only detectable by copy number analysis. All patients with PAX3 mutations had typical phenotype of WS with dystopia canthorum (WS1), whereas patients with MITF gene mutations presented without dystopia canthorum (WS2). In addition, one patient with bilateral hearing loss and blue eyes with iris stroma dysplasia had a de novo missense mutation (p.Arg217Ile) in MITF. MITF 3-bp deletions at amino acid position 217 have previously been described in patients with Tietz syndrome (TS), a clinical entity with hearing loss and generalised hypopigmentation.

Conclusions

On the basis of these findings, we conclude that sequencing and copy number analysis of both PAX3 and MITF have to be recommended in the routine molecular diagnostic setting for patients, WS1 and WS2. Furthermore, our genotype–phenotype analyses indicate that WS2 and TS correspond to a clinical spectrum that is influenced by MITF mutation type and position.

Article summary.

Article focus

The focus of the study was the analysis of variations not described previously, located in the PAX3 and MITF gene concerning their association with the clinical phenotype of Waardenburg syndrome (WS) types 1 and 2.

Key messages

The results of our study indicate that sequencing and copy number analysis of the two genes PAX3 and MITF should be considered in the setting of molecular routine diagnostics for patients with WS and without the symptom dystopia canthorum.

We could demonstrate that one previously described position of the MITF- gene which was shown to be mutated in a patient with Tietz syndrome can be also affected in patients with WS. Therefore, both WS2 and Tietz syndrome most probably correspond to a common clinical spectrum that is influenced by mutation type and position.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Findings of this study are based on the detailed clinical investigation of a mutation positive cohort.

Drawing further qualitative or quantitative conclusions by a comparison between the cohort of mutation positive and the cohort of mutation negative was not done, since clinical data of satisfying quality for all tested negative cases could not be obtained in this setting. Thus conclusions concerning the accuracy of the clinical criteria of inclusion were not drawn.

Introduction

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) is an auditory-pigmentary syndrome that occurs with a frequency of 1 in 40 000.1 WS has been classified into four main phenotypes: type 1 (WS1) is characterised by congenital sensorineural hearing loss, heterochromia iridis, partial hypopigmentation of the hair including premature greying and lateral displacement of the inner ocular canthi (dystopia canthorum). Type 2 (WS2) is distinguished from WS1 by the absence of dystopia canthorum. WS3 or Klein-Waardenburg syndrome is similar to WS1, but includes upper limb abnormalities. WS4 or Waardenburg-Shah syndrome has features of Hirschsprung disease in addition to WS2.

WS is genetically heterogeneous. Point mutations in the PAX3 gene are described to be the most frequent cause of WS1 and WS3.2–4 PAX3 is a member of the mammalian PAX gene family and encodes a DNA-binding transcription factor expressed in neural crest cells.5 It plays an important role for the migration and differentiation of melanocytes, which originate from the embryonic neural crest. The PAX3 gene is structurally defined by the presence of a highly conserved 128 amino acid DNA-binding domain, known as the paired domain, and a second DNA-binding domain, the homeodomain.5 6 PAX3 mutations associated with WS1 include substitutions of conserved amino acids in the paired domain or the homeodomain of the protein, splice site mutations, non-sense mutations and insertions or deletions leading to frame shifts.7 8 All previously published PAX3 mutations in WS1 are heterozygous, whereas both heterozygous and homozygous PAX3 mutations have been described in the allelic disease WS3.1 8–12

Heterozygous mutations in the MITF gene are one category of molecular causes of WS 2.13 14 The MITF gene encodes a transcription factor with a basic helix–loop–helix leucine zipper motif. Proteins with this kind of motif form homodimers or heterodimers by their HLH-zip regions and bind DNA with their basic domain. Another gene that is in the case of mutations associated with WS2 is SOX10.15 In addition, mutations in SOX10, EDN3 and EDNRB were found in WS4.16

The exact description of the mutations responsible for the WS type is of significant importance in genetic counselling of WS patients and their families. Whole gene sequencing enables the discovery of point mutations and small alterations in the gene, but cannot reliably detect whole exon or whole gene copy number changes, which have been reported for many genes resulting in a specific genetic disorder. In recent years, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) has become a widespread method in molecular genetic diagnostics to detect or exclude copy number changes in targeted genes.

We applied both whole gene sequencing and MLPA analysis for the detection of point mutations and copy number variations in the genes PAX3 and MITF, and describe 19 mutations, of which 15 have not been previously reported for patients with features of WS.

Materials and methods

Patients

For 119 patients molecular genetic analyses were requested owing to the clinical suspicion of WS. From this cohort, for 15 Caucasian patients we have identified mutations in PAX3 or MITF that have not been described previously. Furthermore for four Caucasian patients already published alterations were found in one of these genes. Subsequently, more detailed clinical data were collected from these individuals as well as from their clinically affected family members.

Molecular genetic analysis

All 19 patients were analysed for point mutations and copy number changes in the genes PAX3 and MITF. Clinical information and specimens were obtained with informed consent in accordance with German law for genetic diagnostics. Genomic DNA was prepared from white blood cells using a standard procedure. All 10 exons of PAX3 and all 9 exons of MITF were PCR-amplified and directly sequenced. Sequence variant numbering was based on the transcript ENST00000392069 for PAX3 and ENST00000314557 for MITF. Nucleotide numbering used the A of the ATG translation initiation site as nucleotide +1. The nomenclature of the alterations was adopted according to the guidelines of the human variation society (http://www.hgvs.org/). MLPA analysis was carried out to detect or exclude deletions and duplications of the genes PAX3 and MITF. For this purpose MRC-Holland SALSA MLPA P186 was used. The mix of probes was hybridised to template DNA. The probes, which contained a common sequence tail, were ligated, and subsequently amplified by PCR. Products were separated electrophoretically and the signals captured by a CCD camera. To evaluate quantity and size of the fragments the software Sequence Pilot (JSI Medical Systems, Kippenheim, Germany) was used.

Results

Molecular genetic analysis of the genes PAX3 and MITF for 19 unrelated index patients with the clinical phenotype of WS revealed 15 novel and 4 previously published heterozygous mutations (Otable 1). Fourteen mutations occurred in the PAX3 gene: one small insertion, two missense mutations, four non-sense mutations, two small deletions, one splice site mutation and four large deletions comprising at least one exon. Five mutations were detected in the MITF gene: one missense mutation, one non-sense mutation, one large deletion and one large duplication. In addition, the combination of an MITF missense mutation with a small deletion was found in family 11 (table 1). Both mutations were proven to be located on the same chromosome by segregation analysis. The paternal grandfather, a brother, two sisters, a niece and a nephew with WS were all proven to be carriers of these two mutations.

Table 1.

Genotype and phenotype of all Waardenburg syndrome index patients

| Index patient | Mutation description |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | Gene | Gene structure affected | Nucleotide level | Protein level | Type | Transmission mode | Dystopia canthorum | Heterochromia iridis | Hearing loss | Other clinical symptoms | Notes | |

| 1 | 6.5 years | m | PAX3 | Exon 2 | c.111dupC | p.Val38Argfs*76 | Insertion | n.a. | + | + | (+) | Synophrys, low frontal and nuchal hairline, skin hyperpigmentation anomalies | – |

| 2 | 7 years | f | PAX3 | Exon 2 | c.143G>A | p.Gly48Asp | Missense | Maternal | + | − | + | High nasal bridge, synophrys, eyebrow flaring, skin depigmentation; affected family members with premature greying and dystopia canthorum | Different amino acid change at same position described in ref. 22 |

| 3 | 3 years | f | PAX3 | Exon 2 | c.186G>A | p.Met62Ile | Missense | Paternal | + | + | ++ | – | Different amino acid change at same position: described in ref. 23 |

| 4 | 34 years | m | PAX3 | Exon 3 | c.400C>T | p.Arg134X | Non-sense | n.a. | + | + | − | – | – |

| 5 | 6 months | m | PAX3 | Exon 5 | c.589delT | p.Ser197Leufs*19 | Deletion | Paternal | + | − | + | White forelock | – |

| 6 | 3 months | m | PAX3 | Exon 5 | c.655C>T | p.Gln219X | Non-sense | Paternal | + | + | − | High nasal bridge | – |

| 7 | 17 months | m | PAX3 | Exon 5 | c.784C>T | p.Arg262X | Non-sense | Maternal | + | + | + | White forelock, synophrys, high nasal bridge, prognathia, hypopigmentation anomalies | Described in ref. 24 |

| 8 | 1 week | m | PAX3 | Intron 5 | c.793-1G>T | – | Splice site | De novo | + | − | − | White forelock, craniofacial dysmorphism | – |

| 9 | 17 months | m | PAX3 | Exon 6 | c.946_956del | p.Ile317Cysfs*89 | Deletion | n.a. | + | − | + | Unilateral hearing loss | – |

| 10 | 2,5 years | m | PAX3 | Exon 6 | c.955C>T | p.Gln319X | Non-sense | n.a. | + | + | ++ | High nasal bridge, mild skin depigmentation | – |

| 11 | n.a. | m | MITF | Exon 1 | [c.28T>A;c.33+6del7] | p.Tyr10Asn | Missense/deletion | Paternal | − | + | + | – | – |

| 12 | 16 years | m | MITF | Exon 3 | c.328C>T | p.Arg110X | Non-sense | n.a. | − | + | + | – | – |

| 13 | 7 months | m | MITF | Exon 7 | c.650G>T | p.Arg217Ile | Missense | De novo | − | − | + | Blue eyes with hypoplasia of iris stroma, white forelock | Described in ref. 25 |

| 14 | 23 years | m | PAX3 | Entire gene | c.(?_-61)_(1452-33_?) | – | Deletion entire gene | Paternal | + | − | + | Pigmentation anomalies, unilateral hearing loss | Described in ref. 26 |

| 15 | 42 years | m | PAX3 | Exon 7 | c.958+?_1174-?del | – | Deletion exon 7 | n.a. | + | − | + | Pigmentation anomalies | – |

| 16 | 6 years | f | PAX3 | Exons 8–9 | c.1173+?_(1452-33_?)del | – | Deletion exons 8–9 | n.a. | + | − | + | Blue eyes, synophrys, medial eyebrow flaring | – |

| 17 | 5 months | f | PAX3 | Entire gene | c.(?_-61)_(1452-33_?) | – | Deletion entire gene | n.a. | + | + | + | Unilateral hearing loss | Described in ref. 26 |

| 18 | 7 years | m | MITF | 5′-UTR region | c.?_1-70453dup | – | Duplication | n.a. | − | − | (+) | – | – |

| 19 | 3 years | m | MITF | Exons 1–9 | c.1-70433_?_(988_?)del | – | Deletion exons 1–9 | De novo | − | + | + | Bilateral hearing loss | – |

‘De novo’, under consideration of provided information concerning kinship, no paternity testing was performed.

f, female; m, male; (+), mild; +, moderate; ++, severe; n.a., not available.

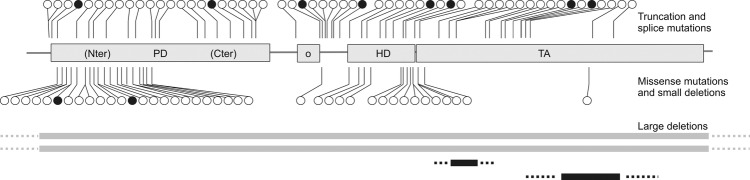

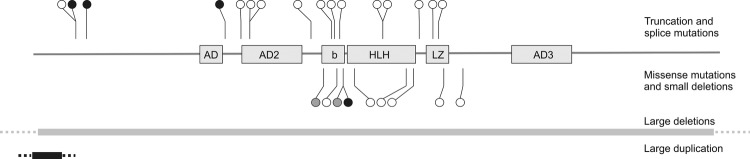

Of specific interest, 6 of the 19 mutations (32%) were not detectable by direct sequencing. There were five large deletions and one duplication that could only be detected by MLPA analysis. In 10 of 19 index patients, parents were available for genetic analysis. Seven mutations were familial (ie, shown to be inherited from 1 parent that presented signs and symptoms of WS), whereas three mutations (1 mutation in PAX3 and 2 in MITF) occurred de novo. However, 15 of 19 mutations detected in PAX3 and MITF represented novel mutations. The positions of these mutations and all previously published mutations are summarised in figure 1 (PAX3 gene) and figure 2 (MITF gene).

Figure 1.

Survey of PAX3 mutations detected in patients with Waardenburg syndrome. Black circles, mutations detected in this study; black bars, copy number variations detected in this study; white circles and grey bars, previously published mutations and deletions. PD, paired domain; o, octapeptide; HD, homeodomain; TA, transactivation domain.

Figure 2.

Survey of MITF mutations detected in patients with Waardenburg and Tietz syndrome. Black circles and bars, mutations and copy number variations detected in this study; white circles and grey bars, previously published mutations and deletions; grey circles, MITF mutations associated with Tietz syndrome. AD1–3, (trans)activation domains; b, basic domain; HLH, helix–loop–helix domain; LZ, leucine zipper domain.

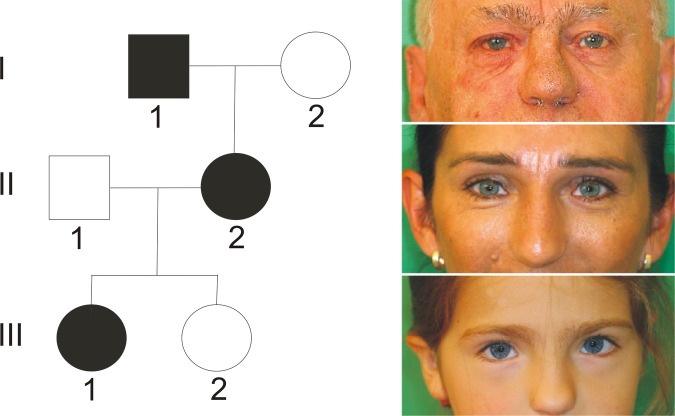

All index patients with PAX3 mutations had the typical phenotype of WS type 1 including dystopia canthorum and at least one of the following criteria: heterochromia iridis, hearing loss and additional features such as white forelock, craniofacial dysmorphism including high nasal bridge, synophrys, eyebrow flaring or anomalies of skin pigmentation (table 1 and figure 3). Detailed clinical information was available from 13 of 14 patients with PAX3 mutations and 11 of these presented hearing loss. No differences in phenotype were noted between patients with PAX3 point mutations and PAX3 deletions.

Figure 3.

Pedigree of index patient 2 with PAX3 mutation. The girl presented with clinical features of Waardenburg syndrome type 1 (see table 1): dystopia canthorum, high nasal bridge, synophrys, eyebrow flaring, skin depigmentation and bilateral hearing loss. Her mother and maternal grandfather had only premature greying.

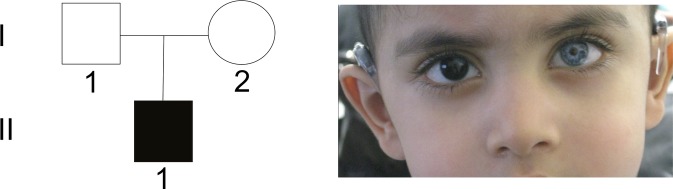

Patients with MITF mutations had the clinical phenotype of WS type 2, that is, heterochromia iridis and/or hearing loss without dystopia canthorum (figure 4). Patient 13, who was found to carry a de novo missense mutation in MITF, did not present with heterochromia iridis, but with blue eyes and hypoplasia of iris stroma.

Figure 4.

Sporadic case (patient 19 in table 1) of Waardenburg syndrome type 2 with MITF mutation. The boy presented with heterochromia iridis and bilateral hearing loss, but did not show dystopia canthorum.

Discussion

Molecular genetic analyses of the PAX3 and MITF gene revealed 15 novel and 4 previously known mutations in patients with the clinical phenotype of WS. Of these, 14 mutations occurred in PAX3 and 5 mutations were found in MITF. The spectrum of mutations includes nonsense, missense and splice site mutations, insertions as well as deletions and duplications.

Most of the novel mutations in PAX3 are localised in exons 2–6 and hence influence functionally relevant domains (table 1 and figure 1). This predominant localisation in exons 2–6 has previously been described.17 Twelve of the 14 PAX3 mutations are truncating mutations including large deletions. Deletions comprised two whole gene deletions and two intragenic deletions of exon 7 and exons 8 and 9, respectively. The two missense mutations are localised in the N-terminal part of the paired domain, which mediates intensive DNA contact. There is no correlation between the mutation type (missense, nonsense and deletion) and the severity of the phenotype. Therefore, loss of protein function leading to haploinsufficiency seems to be the disease-causing mechanism for WS1. All patients with PAX3 mutations had phenotypes of WS1 (table 1 and figure 3).

Five patients had mutations in the MITF gene (table 1 and figure 2). Four of these represented novel mutations. Detailed clinical information was available for all five patients. Four patients had features corresponding to the WS2 phenotype (figure 4). Interestingly, one of these (patient 11) was the first patient with WS2 who was found to carry two MITF mutations (missense mutation and small deletion) within the same gene copy. Since both mutations are novel, it remains to be clarified whether one or the combination of both mutations leads to the WS2 phenotype.

One patient with a de novo missense mutation c.650G>T (p.Arg217Ile) in the MITF gene did not present with heterochromia iridis, but with bilateral blue iridis and hypoplasia of iris stroma (patient 13 in table 1). Interestingly, MITF mutations affecting amino acid position 217, which is located in the basic domain of MITF, were also described in patients with Tietz syndrome (TS, MIM #103500). Compared to WS2, Tietz syndrome is characterised by a more severe phenotype with generalised hypopigmentation and complete hearing loss.18 Instead of heterochromia iridis, which is typical for WS types 1 and 2, patients with Tietz syndrome present with bilateral blue iridis. Till date, only three patients with Tietz syndrome and mutation in the MITF gene have been described.19–21 Two of these with typical Tietz syndrome had a mutation altering amino acid position 217 (3 bp in-frame deletion Arg217). Compared with these patients, our patient with a de novo missense mutation at the same amino acid position has a less severe phenotype with bilateral hearing loss, a white forelock and blue iridis with hypoplasia of iris stroma. These clinical features are part of WS2, while blue eyes with hypoplastic iris stroma may correspond to Tietz syndrome. Apparently, a missense mutation at amino acid position 217 leads to milder or intermediate phenotype than a 3 bp in-frame deletion at the same position. Therefore, both WS2 and Tietz syndrome most probably correspond to a common clinical spectrum that is influenced by mutation type and position.

In summary, the molecular genetic analyses of the PAX3 and MITF genes are important diagnostic steps to explain the molecular cause of clinical features of WS and facilitate genetic counselling of affected patients and their families. For 6 of 19 patients with suspected WS and previously genetically unconfirmed diagnosis, we found either large deletions (4 patients with deletions in PAX3 and 1 patient with deletion in MITF) or duplications (one patient, MITF gene). This indicates that deletion/duplication screening is indispensable for a successful molecular genetic diagnostics of WS. As a genetic diagnostic strategy it is thus recommended to perform both sequence analysis and copy number analysis of the PAX3 and MITF genes in all patients with clinical features of WS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GW and DS were responsible for study concept and design and acquisition of genetic data and interpretation. BZ, LMGN, JW, MS, AB, ABo, CK, SV, GSW, MG and OB collected the clinical data. GW, BZ and DS wrote the manuscript. All authors have critically revised the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Read AP, Newton VE. Waardenburg syndrome. J Med Genet 1997;34:656–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoth CF, Milunsky A, Lipsky N, et al. Mutations in the paired domain of the human PAX3 gene cause Klein-Waardenburg syndrome (WS-III) as well as Waardenburg syndrome type I (WS-I). Am J Hum Genet 1993;52:455–62 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeStafano CT, Cupples LA, Arnos KS, et al. Correlation between Waardenburg syndrome phenotype and genotype in a population of individuals with identified PAX3 mutations. Hum Genet 1998;102:449–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milunsky JM. Waardenburg syndrome type 1. In: GeneReviews at GeneTests: medical genetics information resource [database online], Seattle: University of Washington, 1997–2006. PMID: 20301703 (accessed15 Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart ET, Kioussi C, Gruss P. Mammalian Pax genes. Annu Rev Genet 1994;28:219–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noll M. Evolution and role of Pax genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1993;3:595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin CT, Hoth CF, Macina RA, et al. Mutations in PAX3 that cause Waardenburg syndrome type I: ten new mutations and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet 1995;58:115–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tassabehji M, Newton VE, Liu XZ, et al. The mutational spectrum in Waardenburg syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1995;4:2131–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Saxe M, Kromberg JG, Jenkins T. Waardenburg syndrome in South Africa. S Afr Med J 1984;66:256–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheffer R, Zlotogora J. Autosomal dominant inheritance of Klein–Waardenburg syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1992;42:320–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zlotogora J, Lerer I, Bar-David S, et al. Homozygosity for Waardenburg syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 1995;56:1173–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tekin M, Bodurtha J, Nance W, et al. Waardenburg syndrome type 3 (Klein–Waardenburg syndrome) segregating with a heterozygous deletion in the paired box domain of PAX3: a simple variant or a true syndrome? Clin Genet 2001;60:301–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu XZ, Newton VE, Read AP. Waardenburg syndrome type II: phenotypic findings and diagnostic criteria. Am J Hum Genet 1995;55:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nobukuni Y, Watanabe A, Takeda K, et al. Analyses of loss-of-function mutations of the MITF gene suggest that haplosufficiency is a cause of Waardenburg syndrome type 2A. Am J Hum Genet 1996;59:76–83 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bondurand N, Dastot-Le Moal F, Stanchina L, et al. Deletions at the SOX10 gene locus cause Waardenburg syndrome types 2 and 4. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:1169–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edery P, Attie T, Amiel J, et al. Mutations of the endothelin-3 gene in the Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease (Shah-Waardenburg syndrome). Nature Genet 1996;21:442–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pingault V, Ente D, Dastot-Le Moal F, et al. Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum Mutat 2010;31:391–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tietz W. A syndrome of deaf-mutism associated with albinism showing dominant autosomal inheritance. Am J Hum Genet 1963;15:259–64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izumi K, Kohta T, Kimura Y, et al. Tietz syndrome: unique phenotype specific to mutations of MITF nuclear localization signal. Clin Genet 2008;74:93–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amiel J, Watkin PM, Tassabehji M, et al. Mutation of the MITF gene in albinism-deafness syndrome (Tietz syndrome). Clin Dysmorphol 1998;7:17–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith SD, Kelley PM, Kenyon JB, et al. Tietz syndrome (hypopigmentation/deafness) caused by mutation of MITF. J Med Genet 2003;37:446–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandya A, Xia XJ, Landa BL, et al. Phenotypic variation in Waardenburg syndrome: mutational heterogeneity, modifier genes or polygenic background? Hum Mol Genet 1996;5:497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierpont JW, Doolan LD, Amann K, et al. A single base pair substitution within the paired box of PAX3 in an individual with Waardenburg syndrome type 1 (WS1). Hum Mutat 1994;4:227–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markova TG, Megrelishvilli SM, Shevtsov SP, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic investigation of Waardenburg syndrome type 1. Vestn Otorinolaringol 2003;1:17–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Jiang L, Xie Z, et al. Novel mutations of PAX3, MITF, and SOX10 genes in Chinese patients with type I or type II Waardenburg syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;397:70–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tassabehji M, Newton VE, Leverton K, et al. PAX3 gene structure and mutations: close analogies between Waardenburg syndrome and the Splotch mouse. Hum Mol Genet 1994;3:1069–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.