Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association between self-reported dysmenorrhoea and patterns of female initiation rites at menarche among Amazonian indigenous peoples of Vaupés in Colombia.

Design

A cross-sectional study of all women in seven indigenous communities. Questionnaire administered in local language documented female initiation rites and experience of dysmenorrhoea. Analysis examined 10 initiation components separately, then together, comparing women who underwent all rites, some rites and no rites.

Settings

Seven indigenous communities belonging to the Tukano language group in the Great Eastern Reservation of Vaupés (Colombia) in 2008.

Participants

All women over the age of 13 years living in the seven communities in Vaupés, who had experienced at least two menstruations (n=185), aged 13–88 years (mean 32.5; SD 15.6).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The analysis rested on pelvic pain to define dysmenorrhoea as the main outcome. Women were also asked about other disorders present during menstruation or the precedent days, and about the interval between two menstruations and duration of each one.

Results

Only 17.3% (32/185) completed all initiation rites and 52.4% (97/185) reported dysmenorrhoea. Women not completing the rites were more likely to report dysmenorrhoea than those who did so (p=0.01 Fisher exact), taking into account age, education, community, parity and use of family planning. Women who completed less than the full complement of rites had higher risk than those who completed all rites. Those who did not complete all rites reported increased severity of dysmenorrhoea (p=0.00014).

Conclusions

Our results are compatible with an association between traditional practices and women's health. We could exclude indirect associations with age, education, parity and use of family planning as explanations for the association. The study indicates feasibility, possible utility and limits of intercultural epidemiology in small groups.

Keywords: Intercultural , Dysmenorrhoea, Tradicional medicine, Initiation rites

Article summary.

Article focus

Female initiation rites and dysmenorrhoea.

Epidemiology and cultural safety.

Key messages

There is an association between what women say about abandoning initiation rites and dysmenorrhoea.

The study suggests an association between traditional practices and women's health.

The study proposes the feasibility and usefulness of intercultural epidemiology.

Strengths and limitations of this study

There are no epidemiological studies of indigenous initiation and dysmenorrhoea.

The small numbers’ problem is recognised, even with all eligible women participating.

Introduction

The Tatuyo, Bará, Carapana, Tuyuca and Tukano ethnicities in Tukano language group live between the Papurí and Yapú rivers in the Great Eastern Reservation of Vaupés.1 2 In collective reservations, the seven communities with very similar customs in a subsistence economy. They share traditional rituals around childbirth, management of the umbilicus, rites of sexual début, marriage, pregnancy, menopause and death but, like many traditional cultures, they have abandoned much of this with urbanisation and globalisation of culture.3

Initiation rites at the onset of menarche last 3–5 days, involving a number of discrete activities: each initiate has a Godmother (madrina) and a mentor; she spends 3–5 days in isolation on a strict diet; she receives a blessing or prayer from the traditional healer; she applies powdered carayurú, a vegetable stain (Arrhabidea chica), on her skin; her hair is cut and her body painted with we, another vegetable stain (Bignoniaceae sp); she inhales ají, a hot spice mix (Capsicum spp); and undergoes water-precipitated or plant-precipitated emesis.

According to traditional wisdom, young women will be healthy if they complete initiation rites and follow traditional practices during menstruation. Young women in the region go to residential schools outside their communities. The school year follows a national standard, making it difficult for schoolgirls to participate in traditional rites.4 This loss of culture is a concern for Amazon indigenous communities, where every year people have less to do with traditional medical practices.5 We were unable to confirm a decline or otherwise of initiation rituals from published sources in Colombia. Our research began with the express concern of community elders who, in the course of a decade long partnership with the traditional health systems group at Universidad del Rosario in Colombia, asked if loss of their cultural practices could affect women’s reproductive health, particularly dysmenorrhoea.

Cultural adaptation is less common in epidemiology than it is in some qualitative approaches,6 yet intercultural epidemiology can be useful in identifying potential health benefits of traditional health practices, many of which are being lost as globalisation erodes indigenous cultures.

Problems related to women's reproductive cycle are increasing worldwide.7–9 Western medicine has few satisfactory solutions to offer women with dysmenorrhoea, offering an interesting case in point as the WHO calls to explore possible contributions of traditional medicine.10 11 A sparse epidemiological literature addresses the links with dysmenorrhoea and cultural influences,12 13 ethnicity and religiosity.14 15 Better documented risk factors are diet, exercise, psychological or emotional episodes, and use of alcohol and tobacco.16–20 We found no epidemiological studies of indigenous initiation rites and dysmenorrhoea. A retrospective survey using a questionnaire evaluated this possible association.

Methods

Study population

All women over the age of 13 years living in the seven communities in Vaupés, who had experienced at least two menstruations (n=185), aged 13–88 years (mean 32.5; SD 15.6).

Outcome

Interviewers asked if, during menstruation, women suffered pelvic pain, dizziness, headache, bodily pains and problems in the days prior to menstruation. They did not specify a period of recall or a frequency of problems. They also asked about the interval between two menstruations and duration of menstruation. The analysis rested on pelvic pain to define dysmenorrhoea.21–23 The interviewer asked directly about pain and its severity, without asking about the duration of pain, proportion of menstruations affected or activities that could not be completed owing to the pain. Because pain perception is subjective, we used a well-established graphic approach showing faces with different grades of discomfort (figure 1).24 Respondents simply pointed to the face that reflected their experience during menstruation.

Figure 1.

Wong-Baker faces pain rating scale.

Exposure

Initiation rites at the onset of menarche, lasting 3–5 days, during which time the young women reported one, several or all component rites: emesis, care during the ceremony, carayurú powder, isolation, prescribed diet, body paint with we, Godmother, cut hair, inhaled ají and blessed by traditional healer. The questionnaire documented exposure to each component rite (yes/no) separately. Without understanding the exact workings of the initiation rites, we followed the WHO guideline to handle component activities as a ‘black box’:25 we do not always have to understand exactly how a traditional therapy works to measure its effect. We thus documented each of the individual rites.

Instrument

A month of consultation with local healers (payés) clarified the main research question and a list of culturally appropriate questions. After approval of the questionnaire for semantic and cultural equivalence with the payés, the researchers piloted the questionnaire and pain images with 14 women of the same ethnic group living in Mitu (not part of the study), they reported pain using the graphic approach showing faces with different grades of discomfort. The authorities in each community invited all women—by cultural definition, the first menstruation identifies the woman as an adult—to the communal hall (maloka) where the researchers explained the instrument, issues of confidentiality and the right to decline to participate or to leave out any question. No eligible woman declined to participate. Interviewers administered a 37-question instrument through a translator during December 2008.

Analysis

Epi-data 3.1 served for manual data capture analysis relied on CIETmap 2.0 β 8 (Centro de Investigación de Enfermedades Tropicales, Mexico), public domain software that provides a Windows-like interface with R. Bivariate analysis with each of the 10 component activities examined the relationship of each component rite on its own with dysmenorrhoea. We also analysed complete and incomplete initiation using sequential stratification by age of the woman, community of origin (some had more access to Western ways), education, parity, family planning and menopause. We analysed trend using the Mantel extension of the Mantel-Haenszel test.26 We report results as adjusted OR (aOR) with 95% CIs. The two-tailed Fisher's exact test served for estimation of confidence with the resulting sparse numbers comparisons.

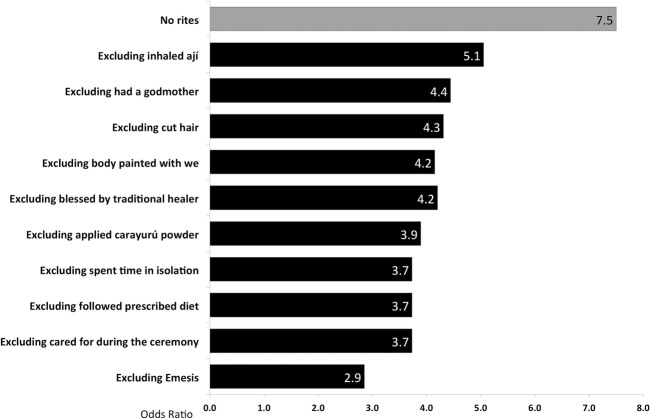

Without any prior basis for weighting importance of different activities in the initiation, we calculated the average effect across the 10 components as though each was a separate exposure; this relied on Meta, an R program. A Forest plot summarises this (figure 2). Compared with occurrence among women who completed all 10 rites of initiation, a sensitivity analysis dropped each initiation rite in turn to test relevance of each in initiation.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of individual initiation rites and risk of dysmenorrhoea.

Control of biases

Involvement of healers and elders in the design guaranteed cultural fit. The questionnaire inquired for current family planning, and if so, which is the method used (plants, pill, injection, condom, pessary, surgery or partner-managed contraception), and duration of use of each method, as this could affect dysmenorrhoea; hormonal pills can diminish pain and intrauterine devices (IUDs) can increase pain. Use of Western contraceptive methods also coincides with Western acculturation. We stratified by contraceptive use to differentiate between the effect of the contraceptive and the initiation rites. To avoid an acculturation bias from interviewing only women who did not go to nearby towns for work, we conducted the study in December when most return to their homes. We took age, menopause and education into account by stratification to limit the differential influence of these on responses.

Ethical aspects

The CIET ethical review committee at the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero and Research Fund at the Universidad del Rosario in Colombia both approved the proposal. The leadership of each community signed formal agreements for data management and sharing with all participants present, after the researchers had explained to all the nature of the study, how data would be used, confidentiality and rights to decline participation.27

Results

A total of 185 women participated, representing 70.6% of the 262 women over the age of 12 years identified in the 2006 census. The 77 women excluded had either migrated from the area or they had not completed two menstruations. Of 158 women who knew their age in years, the average was 32.5 years (mode 19 years, SD 15.6). Respondents reported low levels of education, 28.3% (52/184) with no schooling and only 17.4% (32/184 women interviewed) with secondary education. Few used family planning (11.1% based on 15/135 women of reproductive age) with an average of 4.9 children each (SD 2.7) (table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the women included in the sample

| Variable | Yes |

No |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed ethnicity | 0 | 0% | 185 | 100% | 185 |

| Born in this community | 94 | 51.4% | 89 | 48.6% | 183 |

| Knew her age | 158 | 85.4% | 27 | 14.6% | 185 |

| Menopausal | 50 | 27.0% | 135 | 73.0% | 185 |

| Had had children | 139 | 75.1% | 46 | 24.9% | 185 |

| Using contraceptive methods | 15 | 11.1% | 120 | 88.9% | 135 |

| Using contraceptive pills | 0 | 0% | – | – | – |

| Using IUDs | 2 | 13.3% | – | – | – |

| Using plants | 1 | 6.7% | – | – | – |

| Tubal ligation | 4 | 26.7% | – | – | – |

| Using other methods | 8 | 53.3% | – | – | – |

| Any education level | 133 | 71.9% | 52 | 28.1% | 185 |

| Lives in a community with airstrip | 118 | 65.2% | 63 | 34.8% | 181 |

| Reported dysmenorrhoea | 97 | 52.4% | 88 | 47.6% | 185 |

| Rites completion | |||||

| All rites completed | 32 | 17.3% | 153 | 82.7% | 185 |

| No rites at all | 14 | 7.6% | 171 | 92.4% | 185 |

| Incomplete rite | 139 | 75.1% | 46 | 24.9% | 185 |

IUDs, intrauterine devices

The average age of menarche was 13.8 years (SD 1.16). Some 52% (97/185) reported dysmenorrhoea and 88.6% (164/185) reported undergoing at least some rite of initiation during menarche. Table 2 shows the proportion involved in each of 10 activities identified by traditional healers as the initiation rites. Considering each rite separately, only emesis retained a significant association on its own with dysmenorrhoea, after taking into account the age of the woman, community of origin (some had more access to Western ways), parity, family planning by sequential stratification and adjusting for menopause and education. The Forest plot (figure 2) shows dysmenorrhoea associated with each component rite compared with women who performed no rites. The average effect size was OR 1.66 (95% CI 1.35 to 2.04).

Table 2 .

Exposure to different aspects of initiation rite and risk of dysmenorrhoea (OR)

| Initiation rite | % of all women receiving this rite* | Risk of dysmenorrhoea in each subgroup |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving rite | Not receiving rite | aOR† | 95% CI |

|||

| Emesis | 38.4% | 27/71 | 70/114 | 0.39† | 0.21 | 0.7 |

| Cared for during the ceremony | 76.8% | 69/142 | 28/43 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 1.02 |

| Applied carayurú powder | 84.3% | 78/156 | 19/29 | 0.53 | 0.23 | 1.19 |

| Spent time in isolation | 71.9% | 64/133 | 33/52 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 1.03 |

| Followed prescribed diet | 71.9% | 64/133 | 33/52 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 1.03 |

| Body painted with we | 50.8% | 44/94 | 53/91 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 1.12 |

| Had a Godmother | 50.8% | 45/94 | 50/88 | 0.7 | 0.39 | 1.25 |

| Cut hair | 68.6% | 64/127 | 33/58 | 0.77 | 0.41 | 1.45 |

| Inhaled ají | 49.2% | 45/91 | 52/94 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 1.41 |

| Blessed by traditional healer | 88.6% | 85/164 | 12/21 | 0.81 | 0.32 | 2.04 |

*Total 185 women; no missing data.

† Adjusted for age and level of education in a stratified analysis.

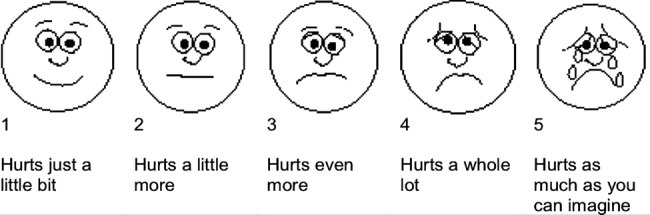

To test the role of each rite in relation to dysmenorrhoea, a sensitivity analysis compared dysmenorrhoea rates among women who performed all 10 rites (n=32) with women who participated in less than 10, dropping each rite in turn. Figure 3 shows the unadjusted odds of dysmenorrhoea for all rites compared with failing to perform specific rites, and those who did not. Those who completed the 10 rites (8/32) contrasted sharply with those who completed some or no rites (89/153) (p Fisher 0.001) (table 3).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis compared dysmenorrhoea risk among women who completed all 10 rites (n=32) compared with women who did not complete at least one rite, and those who completed no rite (listing shows excluded rites).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses of initiation rites and dysmenorrhoea contrasting women who completed all rites with those who completed only one component rite.

| Frequencies |

Risk of dysmenorrhoea |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | No |

Yes |

p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Fisher | |||

| None | 46 | 14 | 30.4 | 32 | 69.6 | 0.001 | 7.5 | 1.95 to 28.7 | 0.001 |

| Emesis | 71 | 39 | 54.9 | 32 | 45.1 | 0.001 | 2.85 | 1.04 to 7.82 | 0.050 |

| Cared for during the ceremony | 142 | 110 | 77.5 | 32 | 22.5 | 0.001 | 3.73 | 1.59 to 8.78 | 0.001 |

| Followed prescribed diet | 133 | 101 | 75.9 | 32 | 24.1 | 0.001 | 3.73 | 1.58 to 8.85 | 0.001 |

| Spent time in isolation | 133 | 101 | 75.9 | 32 | 24.1 | 0.001 | 3.73 | 1.58 to 8.85 | 0.001 |

| Applied carayurú powder | 156 | 124 | 79.5 | 32 | 20.5 | 0.001 | 3.89 | 1.68 to 9.02 | 0.001 |

| Blessed by traditional healer | 164 | 132 | 80.5 | 32 | 19.5 | 0.001 | 4.20 | 1.83 to 9.66 | 0.001 |

| Body painted with we | 94 | 62 | 66.0 | 32 | 34.0 | 0.001 | 4.15 | 1.65 to 10.4 | 0.001 |

| Cut hair | 127 | 95 | 74.8 | 32 | 25.8 | 0.001 | 4.31 | 1.81 to 10.2 | 0.001 |

| Had a Godmother | 94 | 62 | 66.0 | 32 | 34.0 | 0.001 | 4.44 | 1.77 to 11.1 | 0.001 |

| Inhaled ají | 91 | 59 | 64.8 | 32 | 35.2 | 0.001 | 5.05 | 1.99 to 12.77 | 0.001 |

Most respondents with dysmenorrhoea (92/97) reported severity using the Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale. Table 4 shows a statistically significant increase across five levels of severity for those who completed all the rites compared with those who completed any of them or no rites (p=0.0014). It also contrasts with those who did complete no rites with those who completed all rites (p=0.0039).

Table 4.

Completion of initiation rites and reported intensity of dysmenorrhoea

| No dysmenorrhoea | Intensity of dysmenorrhoea |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 and 5 | |

| Incomplete or no rites | 64 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 27 |

| All rites completed | 24 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 88 | 20 | 24 | 20 | 28 |

| OR | 3.94 | 3.49 | 6.76 | 6.92 | |

| 95% CI | 1.72 to 9.00 | 1.41 to 8.64 | 1.84 to 24.93 | 1.17 to 40.88 | |

| Mantel-Haenszel χ2 for trend=10.16 p=0.0014 | |||||

| No rites at all | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| All rites completed | 24 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 28 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| OR | 6.75 | 6.93 | 9.38 | 5.64 | |

| 95% CI | 1.72 to 26.42 | 1.77 to 27.17 | 1.82 to 48.41 | 0.57 to 55.87 | |

| p Fisher | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.2 | |

| Mantel-Haenszel χ2 for trend=8.33; p=0.0039 | |||||

Discussion

Our results show that women who reported having no initiation rite were more likely to report dysmenorrhoea than women who said they underwent such a rite. Emesis was the single strongest protective rite on its own, but sensitivity analysis showed a consistent effect of the other rites for those who did not abandon the initiation practices. The apparent lack of specific effects of each component rite supports the idea that synergy between all components completes the protective effect.

The average age of menarche of our sample was higher than that typically reported in the literature,28–33 possibly indicating a relatively low level of secular change.34 35 That one-half of the women reported dysmenorrhoea (97/185) is lower than that reported in international studies.36–40 Although the local definition (facial expressions) was useful for internal comparisons, it is of limited value in international comparisons.

This study faced several common challenges in intercultural epidemiology. Even with all eligible women participating, the small numbers’ problem is well recognised and has no easy solution.41 42 As anticipated, we found it difficult to untangle issues like use of contraceptives and reporting of age, given the effect of acculturation on these. Despite this interdependence of exposures, we believe we were able to show an independent effect of initiation rites.

Cultural issues probably reduced the effectiveness of the study and reduced the numbers further. The 14.6% (27/185) of women who could not give their age in calendar years is testimony to their distance from Western culture. Analysing only those who mention an age included a cultural filter, limiting our conclusions to those with some measure of Western acculturation. Recall bias might have affected the results as some women had to remember rites that took place decades earlier; a social desirability bias (not wanting to be culturally different, wanting to avoid disapproval) might also have influenced the results. We have no additional information to clarify the directions of these biases.

Within these constraints and the stringent limits imposed by our population size, we tried to take account of other acculturation issues, beyond initiation rites, by stratifying for education, age, parity, community of residence (some had greater access to modern towns) and use of family planning method. The lower risk associated with initiation rites might still be owing to unmeasured lifestyle issues associated with maintaining initiation rites. Solving this issue may require a randomised controlled trial where the differential support for the fulfilment of the rite among communities be contrasted with the occurrence of dysmenorrhoea. One problem with prospective studies in this setting is that it would take many years to accumulate the numbers necessary to make the case.

Since the 1950s, public health programmes have contemplated primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. More recently, primordial prevention identified social, economic and cultural patterns that affect risks.43 Within its limitations, our study is compatible with the idea that primary or primordial prevention of dysmenorrhoea might be possible for indigenous women who are increasingly in contact with Western ways.

Conclusions

Without adding insight into exact mechanisms, this cross-sectional study shows an association between abandoning initiation rites and dysmenorrhoea. None of the rites on its own explains this association.

Intercultural approaches have received little attention in the epidemiological literature, and these need further investment. In this study, the indigenous leaders of the seven communities requested the study and set the research question; they specified the cultural exposures of interest; they participated in the design and testing of instruments; they led interpretation of results; and they are the primary research users, sharing the results with their communities in support of traditional health practices.

Without underestimating the remaining intercultural challenges, the difficulties of research in small populations and the limits of observational studies, we feel this study achieves a first step in culturally safe descriptive epidemiology of traditional medicine: a longer-term dialogue led to the research question and design; the indigenous leaders defined the exposure of interest; the ethical review process fitted with indigenous ethical concepts; it showed an association between self-reported participation in initiation rites and dysmenorrhoea.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Benedicto Mejía and Efraín Mejía, along with other payés (wise men, healers) from the seven communities, participated in formulation of research questions, design and application of the instrument and interpretation of results. Alicia Jaramillo and Guillermina Ferrer translated the questions during the application of the instrument. Carolina Amaya and Natalia Reinoso carried out the pilot study and the research instrument application in the seven communities. Iván Sarmiento helped with data analysis, tables and figures elaboration and revision of citations and bibliographic references. Andrés Cañón and Sebastián Luna collaborated with the systematic review of cultural risk factors for dysmenorrhoea.

Footnotes

Contributors: GZ and NA designed the study, conducted the analysis and wrote the article manuscript. GZ undertook the previous fieldwork for intercultural dialogue with traditional healers, qualitative research and the establishment of the ethical principles ruling this work. NA proposed the formal agreement with communities for data management and sharing. GZ provided oversight and training for fieldwork, and was responsible for the acquisition of the data. NA critically revised successive drafts of the manuscript and the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: Fieldwork was financed by The Research Fund of Universidad del Rosario. GZ carried out the research project as part fulfilment of the requirements of MSc (Epidemiology) at the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Comite de Etica de CIET Universidad Autonoma de Guerrero.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Asatrizy, Gests and Cemi signed a data sharing agreement in 18 May, 2008. Also, there are research authorisation statements from traditional leaders and informed agreements with the participants. This information, including the complete MSc degree thesis, is available in Cemi's document bank (cemi@cemi.org.co).

References

- 1.Dirección de Etnias del Ministerio del Interior y de Justicia Resolución no. 0006 de 26 de enero de 2005, por medio de la cual se inscribe en el registro de asociaciones de autoridades tradicionales y/o cabildos la constitución de la asociación de autoridades tradicionales indígenas de la zona de Yapú—ASATRIZY. Min. Int. Just, Bogotá (CO), 2005

- 2.Sarmiento I, Amaya C. Plan de vida: unidos con un solo pensamiento para vivir bien. Asociación de Autoridades Tradicionales Indígenas de la Zona de Yapú. Bogota, Colombia, 2008

- 3.Reinoso N. Asociación de Autoridades Tradicionales Indígenas de la Zona de Yapú. Historia y origen del proceso de un Nuevo despertar. Bogotá, Colombia, 2008

- 4.Rembeck GI, Gunnarsson RK. Improving pre- and postmenarcheal 12-year-old girls’ attitudes toward menstruation. Health Care Women Int 2004;25:680–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piñeros-Petersen M, Ruiz-Salguero M. Aspectos demográficos en comunidades indígenas de tres regiones de Colombia. Salud Pública Mex 1998;40:324–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron M, Andersson N, Ledogar RJ. Culturally safe epidemiology: oxymoron or scientific imperative. Pimatisiwin: J Aboriginal Indigenous Community Health 2010;8:89–116 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Engaging for health. 11th General Program of Work 2006–2015, a global health agenda, WHO, Geneva (CH), 2006. Working paper GPW/2006-2015. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/GPW_eng.pdf (accessed 15 Oct 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodríguez J. Descripción de la mortalidad por departamentos: Colombia año 2000. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cendex, Bogotá (CO) Working Paper ASS/DT 016-05. http://www.cendex.org.co/pdf/DT016-05.pdf (accessed 15 Jan 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Pérez H, Harlow SD, Erdmann CA, et al. Pelvic pain and associated characteristics among women in northern Mexico. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2010;36:90–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Traditional medicine and health coverage. WHO, Geneva, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization WHO Traditional medicine strategy: 2002–2005. WHO, Geneva, CH, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg S, Sharma N, Sahay R. Socio-cultural aspects of menstruation in an urban slum in Delhi, India. Reprod Health Matters 2001;9:16–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avasarala AK, Panchangam S. Dysmenorrhoea in different settings: are the rural and urban adolescent girls perceiving and managing the dysmenorrhoea problem differently? Indian J Community Med 2008;33:246–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein-Ferber S, Granot M. The association between somatization and perceived ability: roles in dysmenorrhea among Israeli Arab adolescents. Psychosom Med 2006;68:136–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marván ML, Vacio A, García-Yañez G, et al. Attitudes toward menarche among Mexican pre-adolescents. Women Health 2007;46:7–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, et al. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:749–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, Tanksale V, Sahasrabhojanee M, et al. The burden and determinants of dysmenorrhoea: a population-based survey of 2262 women in Goa, India. BJOG 2006;113:453–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balbi C, Musone R, Menditto A, et al. Influence of menstrual factors and dietary habits on menstrual pain in adolescence age. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2000;91:143–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Proctor ML, Murphy PA. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(3):CD002124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parazzini F, Tozzi L, Mezzopane R, et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, and risk of primary dysmenorrhea. Epidemiology 1994;5:469–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazza D. Women's Health in General Practice. Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deb Sh, Raine-Fenning N. Dysmenorrhoea. Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med 2008;18:294–9 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhoea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:428–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong D, Whaley L. Clinical handbook of pediatric nursing. 2nd edn Mosby Company, Saint Louis (MO), 1986. Quoted by: National Institutes of Health, NIH Pain Consortium. Pain intensity scales—Wong-Baker faces pain rating scale [NIH Pain Consortium Web site]. July 17, 2007. http://painconsortium.nih.gov/pain_scales/Wong-Baker_Faces.pdf (accessed 24 Apr 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization General guidelines for methodologies on research and evaluation of traditional medicine. WHO, Geneva(CH), 2000. Working paper WHO/EDM/TRM/2000.1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leuraud K, Benichou J. Tests for monotonic trend from case control data: Cochran-Armitage-Mantel trend test, isotonic regression and single and multiple contrast tests. Biom J 2004;46:731–49 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grupo de Estudios en Sistemas Tradicionales de Salud. Principios éticos para estudios médicos aplicados a los sistemas tradicionales de salud 2008. http://www.cemi.org.co/images/PRINCIPIOS_ETICOS_GESTS_CEMI.pdf (accessed 14 Jun 2010)

- 28.Vera Y, Hidalgo G, Gollo O, et al. Edad de la menarquia y su relación con el estrato social en cinco estados venezolanos. Acta Cient Estud 2009;7:130–5 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulate G. Edad de la menarquia en el Valle Central de Costa Rica y factores asociados a su aparición. Rev Costarric Cien Med 1995;16:37–41 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonseca J, Aguilar O. Edad de la menarquia en San Pedro Sula. Rev Med Hondur 1991;59:4–7 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernández I, Unanue N, Gaete X, et al. Edad de la menarquia y su relación con el nivel socioeconómico e índice de masa corporal. Rev Med Chil 2007;135:1429–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma N, Vaid S, Manhas A. Age at menarche in two caste groups (Brahmins and Rajputs) from rural areas of Jammu. Anthropologist 2006;8:55–7 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romans SE, Martin JM, Gendall K, et al. Age of menarche: the role of some psychosocial factors. Psychol Med 2003;33:933–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padez C. Social background and age at menarche in Portuguese University students: a note on the secular changes in Portugal. Am J Hum Biol 2003;15:415–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanner JM. Growth at adolescence. 2nd edn Blackwell, Oxford, 1962. Quoted by: Korah L. Knowledge and perceptions regarding menstruation among adolescent girls: a research study. Nurs J India 1991;82:205–9 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods NF, Most A, Dery GK. Prevalence of perimenstrual symptoms. Am J Public Health 1982;72:1257–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klein JR, Litt IF. Epidemiology of adolescent dysmenorrhea. Pediatrics 1981;68:661–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson CA, Keye WRJ. A survey of adolescent dysmenorrhea and premenstrual symptom frequency, a model program for prevention, detection, and treatment. J Adolesc Health Care. 1989; 10:317–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamieson D, Steege J. Prevalence of dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:55–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health 2006;6:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andresen EM, Diehr PH, Luke DA. Public health surveillance of low-frequency populations. Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:25–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monasta L, Andersson N, Ledogar RJ, et al. Minority health and small numbers epidemiology: a case study of living conditions and health of children in five foreign Roma camps in Italy. Am J Public Health 2008;98:2035–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonita R, Beaglehole R, Kjellström T. Basic epidemiology. 2nd edn World Health Organization, Geneva, 2006:103 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.