Abstract

Objective

To characterise pregnancies where the fetus or neonate was diagnosed with fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT) and suffered from intracranial haemorrhage (ICH), with special focus on time of bleeding onset.

Design

Observational cohort study of all recorded cases of ICH caused by FNAIT from the international No IntraCranial Haemorrhage (NOICH) registry during the period 2001–2010.

Setting

13 tertiary referral centres from nine countries across the world.

Participants

37 mothers and 43 children of FNAIT pregnancies complicated by fetal or neonatal ICH identified from the NOICH registry was included if FNAIT diagnosis and ICH was confirmed.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Gestational age at onset of ICH, type of ICH and clinical outcome of ICH were the primary outcome measures. General maternal and neonatal characteristics of pregnancies complicated by fetal/neonatal ICH were secondary outcome measures.

Results

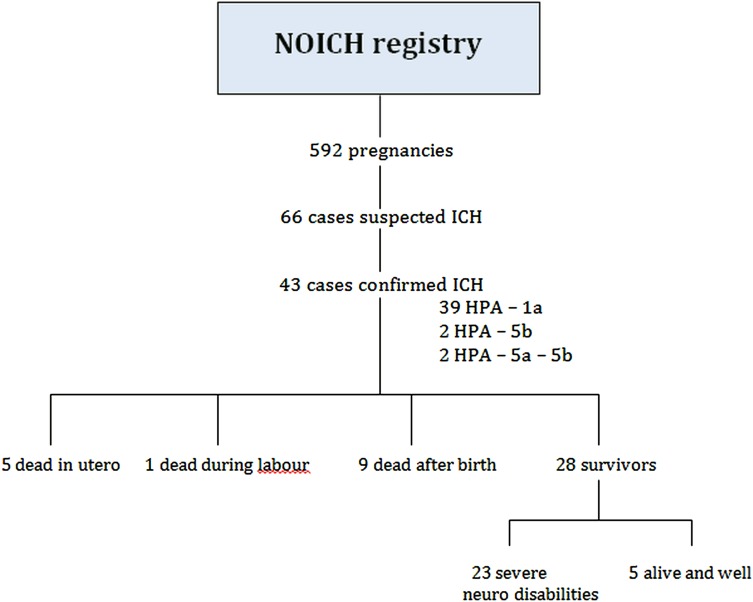

From a total of 592 FNAIT cases in the registry, 43 confirmed cases of ICH due to FNAIT were included in the study. The majority of bleedings (23/43, 54%) occurred before 28 gestational weeks and often affected the first born child (27/43, 63%). One-third (35%) of the children died within 4 days after delivery. 23 (53%) children survived with severe neurological disabilities and only 5 (12%) were alive and well at time of discharge. Antenatal treatment was not given in most (91%) cases of fetal/neonatal ICH.

Conclusions

ICH caused by FNAIT often occurs during second trimester and the clinical outcome is poor. In order to prevent ICH caused by FNAIT, at-risk pregnancies must be identified and prevention and/or interventions should start early in the second trimester.

Article summary.

Article focus

Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT) is the most common cause of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) in relation to thrombocytopenia in term-born infants. Gestational age at time of bleeding onset is important when antenatal treatment options are discussed. No study has specifically addressed this before.

From an international registry of almost 600 FNAIT cases, all recorded cases of ICH were studied in detail. The aim of the study was to characterise pregnancies where the fetus or neonate suffered from ICH caused by FNAIT, with special focus on gestational age at time of bleeding onset.

Key messages

The majority of ICH bleedings occurred by the end of the second trimester and clinical outcome was devastating for most cases. Possible interventions to reduce risk of ICH therefore need to be introduced before the 20th week of gestation.

The majority ICH cases occurred in the first-born child. Most ICH cases will therefore not be recognised in time for treatment if we do not identify pregnancies at risk before the first child is born.

IVIG treatment during the subsequent pregnancy seemed to be protective with regard to ICH in most cases, reducing the ICH recurrence risk from 79% as previously reported, to 11%.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the largest study to date on ICH due to FNAIT. For the first time, gestational age at bleeding onset was assessed in depth. Limitations of this study include that it is a retrospective study, being subject to confounding and information bias.

Introduction

Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT) is the most common cause of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) in relation to thrombocytopenia in term-born infants.1 FNAIT is caused by maternal alloantibodies directed against fetal platelets due to incompatibility in human platelet antigens (HPAs). ICH due to FNAIT is reported to occur in 1:12 500–25 000 births.2 3 The clinical outcome is often more severe than for neonatal ICH from other causes.1 4 The ICH recurrence rate in subsequent pregnancies is reported to be 79%.5 Therapies have been developed that can reduce the incidence of ICH, such as weekly high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).6–8 It is therefore considered important to identify ICH caused by FNAIT in order to treat the mother in subsequent pregnancies. Gestational age at time of bleeding onset is a key factor when antenatal treatment options are discussed since treatment to prevent ICH needs to be started before ICH is likely to occur. No study has specifically addressed this. Identifying common denominators of human HPA-alloimmunised pregnancies complicated by ICH may serve as a future tool to help identify pregnancies at high risk.

The No IntraCranial Haemorrhage (NOICH) registry is a multinational registry including 592 pregnancies complicated by FNAIT from 13 tertiary referral centres across the world. This study presents the results of an in-depth evaluation of all recorded cases of ICH caused by FNAIT from this registry. The aim of the study was to characterise pregnancies where the fetus or neonate suffered from ICH with special focus on clinical and laboratory characteristics and time of bleeding onset.

Materials and methods

Study design and inclusion criteria

All centres that had registered FNAIT cases in the NOICH registry from 2001 to 2010 were invited to participate in this observational cohort study. Pregnancies recorded in the NOICH registry as complicated by fetal or neonatal ICH were identified, and included if both the diagnosis of FNAIT and ICH were confirmed. STROBE guidelines were followed as appropriate.

A case was defined as FNAIT if (1) incompatibility between maternal and paternal/fetal HPA type was confirmed and maternal anti-HPA antibodies were detected, (2) HPA-incompatibility between the mother and father was confirmed and the fetus/neonate suffered ICH and (3) anti-HPA antibodies were detected in the mother but data on fetal/paternal HPA genotype was missing.

Neuroradiological images were recovered and reviewed as electronic copies in a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) using standard display programmes. One Norwegian participant and two of the Dutch participants had MR studies performed in utero. All available neuroradiological images were re-evaluated for this study by an experienced independent paediatric neuroradiologist (OF). The focus of the neuroradiological evaluation was primarily to confirm the ICH diagnosis, second to use imaging to assist in assessing time of bleeding onset and finally to classify the type of bleeding. When images were not available, written reports of the imaging evaluations for the patient files by others were used to evaluate if the ICH diagnosis was correct. Cases where an ICH could not be confirmed were not included in the study.

In cases where information from normal imaging preceding abnormal imaging results was available we were certain of a window in time during which the haemorrhage did occur. In most participants we did not have the benefit of initial normal imaging. Here we used instead well-recognised imaging principles9 in judging the age of haemorrhage from its appearance on CT or MRI and estimated time of onset of bleed from this assessment. According to the classification commonly used in the study of causes of cerebral palsy we classified the haemorrhages as either intraventricular (IVH) and/or periventricular (PVH) or as parenchymal, in brain parenchyma not associated with the central ventricular system.10 The neuroradiological information of likely time of onset was matched to all other clinical information available.

In cases where the fetus or neonate died, autopsy reports were retrieved and studied to evaluate whether ICH diagnosis was certain or unlikely. All reports from post-mortem examinations were evaluated by an experienced perinatal pathologist (NP). Only cases evaluated to be certain ICH were included.

Laboratory data

All laboratory data except maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels were collected from the NOICH registry database (http://www.NOICH.org).

Maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels, except for the Finnish cases (four pregnancies), were measured at the National reference laboratory of clinical platelet immunology in Tromsø, Norway, by quantitative MAIPA.11 Reproducibility between Norwegian and Finnish quantitation was secured by double analysis of some sera samples in both Norway and Finland. In cases where several anti-HPA-1a antibody level measurements were available, the highest maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody level measured during pregnancy or postpartum was included in the study.

The lowest platelet count recorded in the fetus or new-born before any platelet transfusions were given, was included.

Clinical data

Clinical data were mainly collected from the NOICH registry database (http://www.NOICH.org). Additional clinical information was retrieved from the original medical records by each country coordinator.

The pregnancy where ICH was detected for the first time was referred to as the index case. A subsequent ICH event was defined if ICH was recorded in any subsequent pregnancies after the index ICH case.

Statistics

All data were analysed using SPSS software (V.18.0 SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The p<0.05 was considered significant. Means with 95% CIs or median with range were calculated for all continuous variables. Independent sample t test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used as appropriate. One-way analysis of variance test was used to test clinical outcome in relation to time of bleeding onset.

Results

From the NOICH registry recording 592 FNAIT cases, 66 pregnancies from 57 women were initially identified with suspected ICH. In 23 cases, ICH or FNAIT diagnosis could not be confirmed. In total, 43 confirmed cases of ICH due to FNAIT were recorded from 37 mothers. The 43 cases studied were included from the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Norway and the UK (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study population.

Laboratory characteristics of ICH cases

HPA-1a alloimmunisation was found to be the cause in 39 of 43 ICH cases (91%). Anti-HPA-5b antibodies were found in two further cases. In one woman with records of two ICH cases, incompatibility in the gpIa/IIa system was confirmed and in one of her ICH pregnancies anti-HPA-5 antibodies were detected.

Data on maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels during pregnancy or after delivery were available for 15 (35%) of the FNAIT pregnancies complicated by ICH. The median (range) highest anti-HPA-1a antibody level was 105 IU/ml (39–264 IU/ml). In two pregnancies we have serial anti-HPA-1a antibody level measurements starting in the first trimester, and in both these pregnancies the anti-HPA-1a antibody levels fell from the first to the third trimester. The ICH occurred between 28 and 34 weeks in these pregnancies. The median anti-HPA-1a antibody levels measured during the first, second, third trimesters and postpartum did not differ significantly from each other or from the overall median highest antibody level (data not shown).

The median (range) lowest fetal/neonatal platelet count for ICH cases was 8×109/l (1–27). In comparison, median (range) neonatal platelet count for previous or subsequent pregnancies where no ICH was detected, was 17×109/l (1–199) and significantly higher when compared with ICH cases (Kruskal-Wallis test, p=0.004).

Clinical characteristics of ICH pregnancies

Maternal characteristics for all ICH cases are shown in table 1. In the group of the 37 index cases, 26 (70%) cases were first born children. However, most mothers had been pregnant before they had their first child: Eight women had one or more first trimester miscarriages and six women had one or more second trimester losses. For two women, we lack data on gravida status. The mothers were primigravidae in only 10/37 (27%) index cases. In total, 10 mothers (23%) experienced one or more second trimester miscarriages (altogether 20) before or after the ICH case.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of ICH-affected pregnancies

| Maternal characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Maternal age in years, mean (95% CI) | 29.3 (27.6 to 31.0) |

| Obstetrical history | |

| Primigravida, n (%) | 10 (23) |

| First-born child, n (%) | 27 (63) |

| Second trimester miscarriage, n (%) | 10 (23) |

| Pre-eclampsia in this pregnancy, n (%) | 3 (7) |

| Vaginal delivery of ICH neonate, n (%) | 22* (51) |

| Caesarean section of ICH neonate, n (%) | 20* (47) |

| Fetal/maternal treatment | |

| IVIG, n (%) | 4 (9) |

| Steroids, n (%) | 1 (2) |

| Intrauterine platelet transfusion, n (%) | 3 (7) |

| No treatment | 36 (84) |

*Mode of delivery was not known for one ICH pregnancy.

ICH, intracranial haemorrhage; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

Antenatal treatment was given in 4/43 (9%) of the pregnancies complicated by fetal/neonatal ICH. In three cases IVIG was given, two of these fetuses received additional intrauterine platelet transfusions. One mother received corticosteroids as single treatment from 6 weeks gestation onwards, due to two previous second trimester miscarriages (not identified as FNAIT related). For the 37 index cases, only one mother received antenatal treatment. In this case, IVIG treatment was started from week 7 due to autoimmune thrombocytopenia in the mother.

Twenty of 43 mothers with pregnancies complicated by fetal/neonatal ICH were delivered by caesarean section (CS); CS was performed in nine cases with abnormal fetal cerebral ultrasound (US) as main indication.

A high proportion of the pregnancies complicated by ICH were ended preterm: 29 of 43 children (67%) were born before 37 weeks and 4 children were born before 28 weeks. Abnormal US scan with detection of ICH was the main reason for premature delivery (table 2).

Table 2.

Preterm birth

| Reason for preterm delivery | Number of pregnancies (percentage of total) |

|---|---|

| Abnormal ultrasound scan (ICH detected) | 15* (52) |

| Intrauterine fetal demise | 5* (17) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction/pre-eclampsia | 3 (10) |

| Spontaneous preterm birth | 4 (14) |

| Not known | 2 (7) |

| Total | 29† (100) |

*One case was a complication during cordocentesis.

†Including one twin pregnancy.

ICH, intracranial haemorrhage.

Five (12%) of the infants died in utero and one (2%) died during labour. Neonatal characteristics of the live-born children are shown in table 3. Nine children died within the first 4 days after delivery. Most of the survivors developed neurological sequelae: 8 infants were diagnosed with cerebral palsy, 10 were reported to be moderate/severely mentally retarded or severely disabled, 7 neonates were reported to have epilepsy and 4 were blind or with severely reduced vision. In addition, one case of autism and one case of impaired hearing were reported. More than one neurological complication was reported in several cases. Five (14%) of surviving neonates with ICH were reported to be alive and well at time of discharge after delivery, but data on long-term clinical outcome is missing (figure 1).

Table 3.

Clinical outcome characteristics of ICH cases

| Characteristic | Result |

| All ICH cases | |

| Gestational age at delivery, median (range) in weeks | 35 (23–42) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD) in grams | 2274 (832) |

| Sex, female/male | 14/28 |

| Stillborn | 6 (14) |

| Live-born children | 37 (86) |

| APGAR score <7 after 5 min, n (%) | 8 (23) |

| Lowest platelet count (range)×109/l* | 8.9 (1–27) |

| Neonatal death, n (%) | 9 (21) |

| Alive and well at discharge, n (%) | 5 (12) |

| Alive with neurological sequelae, n (%) | 23 (53) |

*Data available for 32 pregnancies.

ICH, intracranial haemorrhage.

The fetuses/neonates were male in the majority (65%) of ICH cases. There was no significant difference in maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels, birth weight, APGAR scores or platelet counts when comparing boys and girls (independent sample t test, p>0.05).

Ten (23%) ICH neonates were below the 10th percentile for birth weight and defined as small for gestational age (SGA) according to standard growth curves. All SGA cases except one were boys.

Bleeding characteristics

Neuroradiological studies were used to review and confirm 19 ICH cases. The remaining 24 ICH cases were confirmed using descriptions of radiographic material by local radiologists.

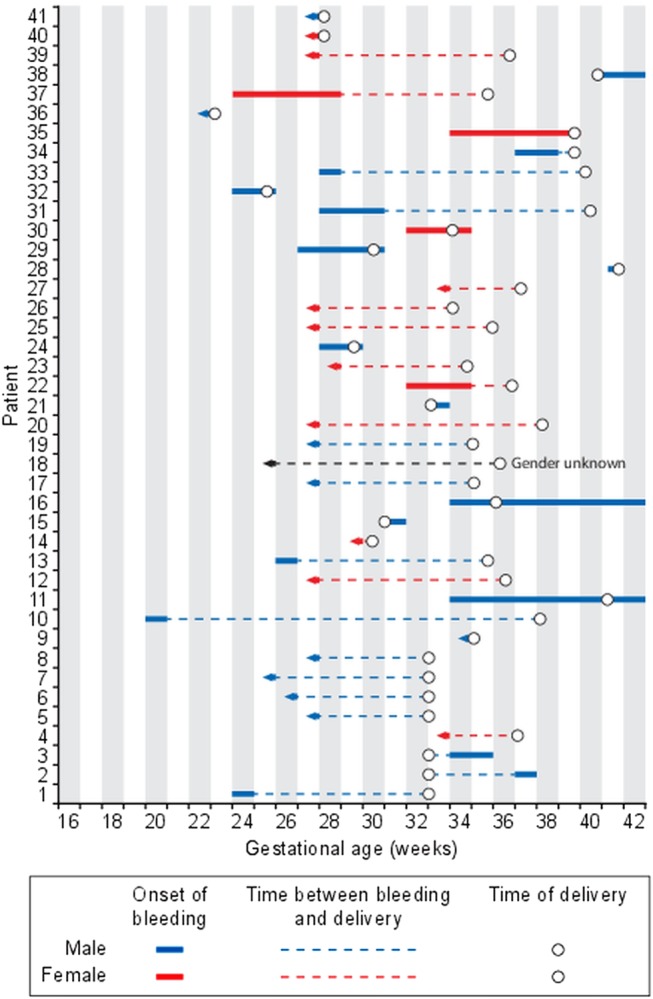

The estimated time of bleeding onset for each ICH case is shown in figure 2. The figure demonstrates that many bleedings started early, and that in most cases several weeks passed between bleeding onset and delivery. More than half (23/43, 54%) of the bleedings happened around gestational week 28 or earlier. In 16 (70%) of the 23 cases with bleeding onset before the third trimester we do not know the exact time of bleeding onset, only that the bleeding started no later than 28 weeks (figure 2). Twenty-nine of 43 bleedings (67%) started before 34 gestational weeks. No cases of intrapartum ICH bleedings were confirmed. The time of bleeding onset in the 10 primigravid cases were not different from the multigravid ICH cases.

Figure 2.

Estimated time period for the onset of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) is shown for 41 cases of ICH caused by fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. An arrowhead to the left indicates that the earliest time of onset cannot be estimated, only that the bleeding occurred before the gestational age indicated on the x-axis.

There was no difference in clinical outcome in relation to time of bleeding onset (data not shown). However, it is noteworthy that perinatal death occurred in two girls (14%) where the bleedings were found to have happened before 30 weeks. In boys, perinatal death occurred in 13 (46%) cases with bleedings happening also at a later gestational age.

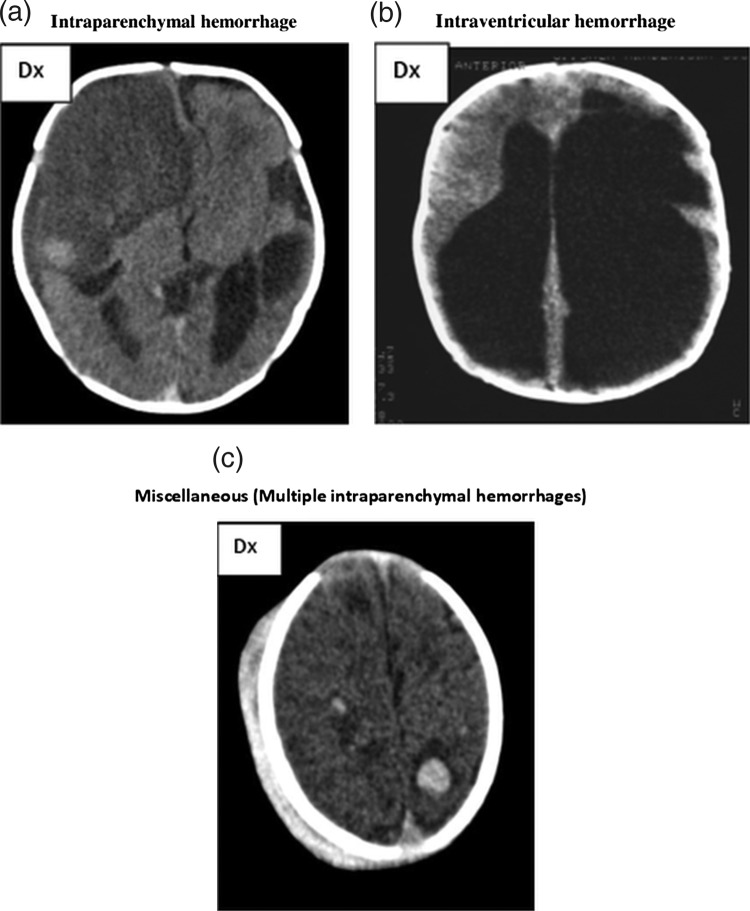

Intraparenchymal haemorrhages were found in 11 of 13 cases where the bleeding occurred during the third trimester or after delivery. Figure 3A illustrates intraparenchymal haemorrhage.

Figure 3.

(A) CT scan shows a very large intraparenchymal haemorrhage with mass effect and occupying most of the right frontal lobe in a term baby. Note a second but smaller haemorrhage on the left side adjacent to the ventricle but separate from this. The attenuation of both haemorrhages indicates that the haemorrhage is several weeks old at the time of imaging. We estimated the right haemorrhage to be 4–6 weeks old and the left still a couple of weeks older. The pregnancy was considered normal, and no intravenous immunoglobulin treatment was given. A live boy was born vaginally at 40 gestational weeks with petecchiae. The platelet count was 6×109/l. (B) This CT shows marked ventriculomegaly, partly due to hydrocephalus, partly due to loss of brain tissue in the left hemisphere. Note the very large ventricle on the left side occupying most of the left hemicranium. The shape of the left lateral ventricle is irregular and that of residual from a previous intraventricular haemorrhage with a paraventricular atrophic defect caused by an old periventricular haemorrhagic infarction. This pattern is pathognomonic for this condition even though no actual blood can be detected. The interpretation of this image is that of an intraventricular haemorrhage associated with a periventricular haemorrhagic infarction timed at 28–30 gestational weeks or earlier. Hydrocephalus was diagnosed intrapartum because of breech presentation. A live boy was born at term with a platelet count of 4×109/l. The child had severe cerebral palsy and a hydrocephalus shunt. (C) The CT scan shows multiple focal intraparenchymal haemorrhages throughout both cerebral hemispheres. Most haemorrhages are quite small. Note also the extensive extracranial subgaleal haemorrhage overlying the right hemicranium. All bleedings are of same age and maximum 7 days old. It was noted that the fetus was small on ultrasound scan at 25 weeks, but otherwise the pregnancy was considered normal. At 42 weeks a live boy was born vaginally, with multiple petecchiaes and multiple retinal bleedings. The platelet count at delivery was 14×109/l, with nadir value 8×109/l. He received platelet transfusions. At time of discharge the boy was described as alive and well, but we do not have data on long-term clinical outcome.

In five cases, multiple bleeding episodes were found. All second bleedings occurred after 33 weeks (range 33–37 weeks). These five cases were all due to HPA-1a alloimmunisation.

Fifteen ICH cases were classified as intraparenchymal and 13 cases as IVH/PVH (figure 3B). Five cases were classified as miscellaneous (figure 3C), whereas 10 cases could not be classified. Among cases where ICH was found to occur before 28 weeks, all but one case was found to be IVH/PVH.

Treatment and clinical outcome in subsequent pregnancies

ICH was detected in six (23%) subsequent pregnancies. One woman had records of ICH in two subsequent pregnancies after the index ICH case. In most subsequent pregnancies (20/26, 77%), no ICH was found.

In 19/26 (73%) of subsequent pregnancies, the mothers received antenatal treatment (IVIG). The IVIG schedules varied greatly, with a median starting time at 18 weeks (range 16–35 weeks). In the six cases where ICH was detected in subsequent pregnancies, three received IVIG treatment. However, in one of these cases IVIG treatment was started after ICH was detected. Therefore, IVIG treatment failed to prevent ICH in 2 (11%) of 19 cases. These two treatment failures were from the same woman. It should be commented that the obstetrical history of this woman is particularly severe with regards to FNAIT complications. The ICH recurrence rate was therefore 11% in IVIG treated pregnancies. Compared with historical data reporting 79% risk of ICH recurrence in FNAIT,5 our data indicate that IVIG was effective in preventing ICH.

In seven cases, no IVIG treatment was given during a subsequent pregnancy after ICH was detected in a previous pregnancy. Five of these untreated pregnancies come from Norway, where IVIG is not routinely given as treatment during HPA alloimmunised pregnancies. ICH occurred in three of these seven cases.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that the majority of ICH bleedings occurred by the end of the second trimester and that clinical outcome was devastating for most cases. The high frequency of bleedings occurring before 28 weeks indicates that the fetus may be severely affected already in the second trimester.

This is the largest study to date on fetal/neonatal ICH caused by FNAIT. For the first time, time of bleeding onset was assessed using clinical information together with radiographic imaging and autopsy reports. The in-depth study of both laboratory and clinical information was carried out in close collaboration between obstetricians, immunologists, perinatal pathologists and specialists in neuroradiology. Limitations of this study include that it is a retrospective cohort study, being subject to confounding and information bias. A bias towards inclusion of the more severe ICH phenotype may be considered. The ICH cases in this study were collected from five different countries and therefore reflect several institutions’ clinical experiences. There is obvious heterogeneity in antenatal treatment for FNAIT between these countries. However, since most of the patients affected by fetal ICH did not receive antenatal treatment, we consider the study population uniform and representative of a larger population.

Some earlier studies have suggested the onset of bleedings to be in the third rather than the second trimester,3 12 and are in variance with this study. The judgement of the onset of cerebral bleeding in this study was cautious, and the onset was probably in many cases even earlier than we report. However, previous studies included too few cases to address this question in an adequate manner. Also, and more importantly, other studies report the gestational age when the ICH was diagnosed, and did not assess when the bleeding may have occurred. In a recent study by Bussel et al,13 antenatal management to prevent recurrence of ICH caused by FNAIT was studied. Gestational age at the time of ICH is reported in this study, but without any data with regard to how the timing of ICH was assessed. These data are therefore difficult to assess, but in support of our data they report that as many as 8/37 (22%) of ICH cases in their study population occurred before 28 gestational weeks. Most of the ICH cases occurred in boys, and the bleedings were more often lethal when the fetus was male. The finding that 80% of the SGA neonates in our population were boys supports the recently published observation that birth weight in boys, but not in girls, was associated with maternal anti-HPA-1a antibodies.14 Data on maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels in FNAIT pregnancies complicated by fetal/neonatal ICH have not been published before.

Fetal ICH due to FNAIT often occurred in the first child. Most ICH cases will therefore not be recognised in time for treatment or prophylactic measures if we do not identify pregnancies at risk before the onset of the bleeding. The high number of first-born children in the study population may not necessarily mean that the risk of ICH caused by FNAIT is genuinely higher in the first-born child. The distribution could be skewed towards nulliparous women since these women may choose not to have more children due to high recurrence risk. Further, most of these women received antenatal treatment during the subsequent pregnancy thereby reducing the incidence of ICH in the younger siblings. Nevertheless, this finding challenges the current management strategy where antenatal treatment is given in subsequent pregnancies after FNAIT has been diagnosed in the first child. A majority of these children will suffer from bleeding already in the second trimester or in the early part of the third trimester. Possible interventions to reduce risk of ICH need to be introduced before the 20th week of gestation. In most children the ICH was either fatal or induced severe disabilities. Our findings therefore support the idea of identifying HPA-1bb mothers with anti-HPA-1a antibodies in all pregnancies3 15 and working towards a prophylactic approach to prevent the immune response against HPA-1a.16 17 The rate of prematurity and CS was high in our study. Many of these patients required delivery before term due to problems related to the fetal ICH such as fetal distress, lack of fetal movements, abnormal US scan, etc. Thus, the present study does not indicate that FNAIT per se is associated with an increased risk for prematurity.

There were no confirmed cases of ICH occurring intrapartum in this study, and only two bleedings occurred after delivery. This could suggest that mode of delivery may not be so important in the prevention of ICH. However, the high CS rate in this study population may have contributed to the low number of intrapartum bleedings. Whether or not delivery by CS prevents ICH needs to be further addressed.3 18 The present study suggests that IVIG treatment during pregnancy is protective in regard to ICH in most cases, which is in accordance with previous studies.13 However, it is an open question whether IVIG would have protected the first born child from ICH, or whether there is a genuine increased risk of ICH in the first born child. Further, it remains to be established if there is also a milder phenotype of ICH with discrete symptoms and better outcome. This question can only be addressed in prospective studies including general screening and repeated fetal US examinations. The maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels were extremely high among ICH cases in this study. Maternal anti-HPA-1a antibody levels may therefore be useful to identify pregnancies at risk for fetal ICH, but these findings need to be evaluated in larger prospective studies. Finally, why boys seem to be more susceptible to maternal anti-HPA-1a antibodies is currently not known and needs further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Eline S Van den Akker, MD, PhD, Amsterdam, the Netherlands for her initial work setting up the NOICH database and registry. No compensation was received for this contribution.

Footnotes

Contributors: MW, AH and HT designed the study. HT, AH and MW carried out the data analyses. HT drafted the manuscript. All authors commented on the drafts of the manuscript and contributed to the final version. AH and MW are guarantors of the study. All authors, external and internal, had full access to all the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: ALD had support from UCLH/UCL by funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme for the submitted work (grant number: xz-482). The funder had no part in the design or execution of the study or the analysis and interpretation of the results.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that (1) no support from any organisation for the submitted work; (2) AH has stocks in Prophylix Pharma AS trying to develop a prophylaxis against HPA-1a immunisation that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; (3) their spouses, partners, or children have no financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work and (4) none of the authors have non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethics approval: All ethics approvals were obtained on a National level, based on local regulations: Sweden, ‘Regionala etikprövningsnämnden’, approval number 2005/2:1. Norway, the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics, North Norway, approval number 2006/1585. UK: The study was done as part of institutional performance, and it received institutional review board exemption. The Netherlands: Ethics approval was waived by the IRB of the LUMC. Finland: The study was based on the NAIT registry kept by the Finnish Red Cross Blood Service according to the Finnish law.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statements: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mao C, Guo J, Chituwo BM. Intraventricular haemorrhage and its prognosis, prevention and treatment in term infants. J Trop Pediatr 1999;45:237–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williamson LM, Hackett G, Rennie J, et al. The natural history of fetomaternal alloimmunization to the platelet-specific antigen HPA-1a (PlA1, Zwa) as determined by antenatal screening. Blood 1998;92:2280–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamphuis MM, Paridaans N, Porcelijn L, et al. Screening in pregnancy for fetal or neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: systematic review. BJOG 2010;117:1335–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jocelyn LJ, Casiro OG. Neurodevelopmental outcome of term infants with intraventricular hemorrhage. Am J Dis Child 1992;146:194–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radder CM, Brand A, Kanhai HH. Will it ever be possible to balance the risk of intracranial haemorrhage in fetal or neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia against the risk of treatment strategies to prevent it? Vox Sang 2003;84:318–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamphuis MM, Oepkes D. Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: prenatal interventions. Prenat Diagn 2011;31:712–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanhai HH, Porcelijn L, Engelfriet CP, et al. Management of alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Vox Sang 2007;93:370–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacheco LD, Berkowitz RL, Moise KJ, et al. Fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. A management algorithm based on risk stratification. Obstet Gynecol 2012;118:1157–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osborn AG. Imaging of intracranial hemorrhage. Diagnostic neuroradiology. St Louis: Mosby, 1994:158–73 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bax M, Tydeman C, Flodmark O. Clinical and MRI correlates of cerebral palsy. JAMA 2012;296:1602–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiefel V, Santoso S, Weisheit M, et al. Monoclonal antibody—specific immobilization of platelet antigens (MAIPA): a new tool for the identification of platelet-reactive antibodies. Blood 1987;70:1722–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer JA, Burrows RF. Feto-maternal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: a literature review and statistical analysis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;41:45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bussel JB, Berkowitz RL, Hung C, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in alloimmune thrombocytopenia: stratified management to prevent recurrence in the subsequent affected fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:135–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiller H, Killie MK, Skogen B, et al. Platelet antibodies and fetal growth: maternal antibodies against fetal platelet antigen 1a are strongly associated with reduced birthweight in boys. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;91:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Killie MK, Tomter G, et al. A screening and intervention program aimed to reduce mortality and serious morbidity associated with severe neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2007;110:833–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjeldsen-Kragh J, Ni H, Skogen B. Towards a prophylactic treatment of HPA-related foetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Curr Opin Hematol 2012;19:469–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiller H, Killie MK, Chen P, et al. Toward a prophylaxis against fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: induction of antibody-mediated immune suppression and prevention of severe clinical complications in a murine model. Transfusion 2012;52:1446–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den AE, Oepkes D, Brand A, et al. Vaginal delivery for fetuses at risk of alloimmune thrombocytopenia? BJOG 2006;113:781–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.