Abstract

Objectives

To assess how much the association between migraine and depression may be explained by various measures of stress.

Design

National Population Health Survey is a prospective cohort study representative of the Canadian population. Eight years of follow-up time were used in the present analyses.

Setting

Canadian adult population ages 18–64.

Participants

9288 participants.

Outcome

Incident migraine and major depression.

Results

Adjusting for sex and age, depression was predictive of incident migraine (HR: 1.62; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.53) and migraine was predictive of incident depression (HR: 1.55; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.08). However, adjusting for each assessed stressor (childhood trauma, recent marital problems, recent unemployment, recent household financial problems, work stress, chronic stress and change in social support) decreased this association, with chronic stress being a particularly strong predictor of outcomes. When adjusting for all stressors simultaneously, both associations were largely attenuated (depression–migraine HR: 1.30; 95% CI 0.80 to 2.10; migraine–depression HR: 1.19; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.66).

Conclusions

Much of the apparent association between migraine and depression may be explained by stress.

Keywords: Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

To understand how much and what kind of stressors play a role in explaining the comorbidity seen between migraine and major depression.

Key messages

Migraine headache and major depression each predict the other prospectively.

Stress, particularly chronic stress, appears to explain much of the association seen between migraine and major depression.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Large, representative, prospective cohort study.

Migraine was self-reported with a single question at each assessment.

Introduction

Several studies support that migraine and psychopathologies, in particular major depression, often co-occur.1–15 In a recent review of such comorbidities, Antonaci et al16 reported a meta-analysis of 12 studies, concluding that the OR may be near 2.2 for major depression and migraine. A limited number of prospective studies have examined the temporality of this association, largely concluding the predictive relationship is bidirectional (ie, migraine status predicts depression onset and vice versa).1 2 10 While the correlation has been well established, the mechanisms for this co-occurrence are less clear; causal paths may exist from one disorder to the other, and/or some shared common risk factor(s) (ie, confounders) may cause both depression and migraine.

Migraine and depression indeed share several risk factors, and thus any perceived correlation between the two could potentially be due to this confounding. Prior research assessing their association has adjusted primarily for demographic variables; some studies have separately studied other risk factors of a genetic and neurobiological nature. Few studies, however, have focused on stress, a known risk factor for both migraine and depression. In Modgill et al's10 analyses of the National Population Health Survey (NPHS), a representative longitudinal study of the Canadian population, childhood trauma attenuated the association between the two disorders, particularly for the direction of depression predicting migraine onset. However, their analyses only looked at a limited number of stressors and did not attempt to address specifically how much different types of stressors may contribute to this association. A variety of stressors may confound the migraine–depression association, as many types have been found to be risk factors for both disorders: for example, childhood trauma,10 17 unemployment,18 19 chronic/repeated stress,20 21 etc.

In the current study, we extend Modgill et al's findings in the NPHS to assess how much the association between migraine and depression may be explained by various measures of stress, including a wide variety of prior and current stressors. We assess this association longitudinally and bidirectionally.

Methods

Sample

The NPHS is a prospective, nationally representative study conducted by Statistics Canada that has followed a Canadian cohort since 1994/1995. At study inception, individuals were randomly selected using a stratified two-stage sample design (n=17 276). The sample has been contacted every 2 years, with the most recent data collection in 2008/2009.

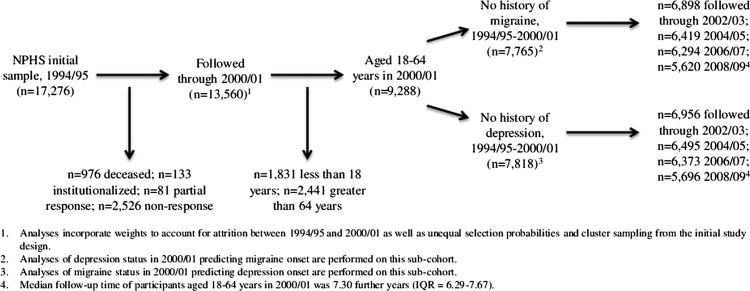

For the purposes of this study, we restricted our sample to individuals aged 18–64 years in Cycle 4 (2000/2001), with this assessment treated as ‘baseline’ in the presented analyses. This serves two purposes: (1) as both migraine and depression assessments reflect current states rather than diagnostic histories, this allows us to use the first three assessments to construct a several-year history of each disorder prior to baseline and (2) as some of the stressors were not assessed until this time (eg, work stress, chronic stress) or could not be constructed without at least two assessments (eg, change in social support, marital status or employment), this allows a more complete analysis of the role of stressors in the migraine–depression comorbidity. Further information on our analytic sample is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of sample inclusion and exclusion during study period.

Depression

Major depressive episodes are assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form for Major Depression (CIDI-SFMD) at all eight cycles. The CIDI-SFMD inquires about symptoms of major depression, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV, during the preceding 12 months. Kessler et al22 showed that the CIDI-SF has 93% classification accuracy for major depressive episode when compared with the full-length CIDI. Individuals who endorse five or more symptoms during a single 2-week period are considered to have a 90% probability of having major depression;22 for the purposes of this study, such individuals will be considered as having major depression during that year.

Migraine

Migraine is assessed in a single diagnostic question at each assessment. In the first three assessments (1994/1995; 1996/1997; 1998/1999), subjects were asked whether they currently were having migraine headaches that had been diagnosed by a health professional. In the subsequent five assessments (2000/2001; 2002/2003; 2004/2005; 2006/2007; 2008/2009), subjects were asked whether they currently have migraine headaches. In these last five assessments, subjects were further asked about the timing of onset of the diagnosis.

Stressors

Using similar definitions as previous studies using NPHS data,17 we defined several types of stressors: childhood trauma, recent marital problems, recent unemployment, recent household financial problems, work stress, chronic stress and change in social support. Childhood trauma was assessed in Cycle 1 (1994/1995) for those 18 or older at that time, and in Cycle 4 (2000/2001) for the rest of our cohort. Subjects were asked about seven items of childhood trauma occurring prior to the individual turning 18: parental divorce, a lengthy hospital stay, prolonged parental unemployment, frequent parental alcohol or drug use and physical abuse. Childhood trauma was categorised as none, one event and two or more events. Three recent stressful life changes were defined: marital problems, recent unemployment and household financial problems. Marital problems were defined by a change from reporting single, married or partnered in Cycle 3 (1998/1999) to divorced, widowed or separated in Cycle 4 (2000/2001). Recent unemployment was defined as being employed in Cycle 3 (1998/1999) but reporting unemployment or not being in the labour force in Cycle 4 (2000/2001). Household financial problems were defined as having a score above Statistic Canada's low-income cut-off (LICO) in Cycle 3 (1998/1999) followed by a score below the cut-off in Cycle 4 (2000/2001). The LICO score takes into account the individual's income relative to the community in which an individual lives and the size of their household.23 24 Work stress was measured in Cycle 4 (2000/2001) by 13 questions that assessed job security, autonomy, conflict and satisfaction;24 the score was categorised by quartiles. Chronic stress was measured in Cycle 4 (2000/2001) by 18 questions that assessed stress in one's personal life, focusing primarily on relationships and family strife;24 this score was also broken into quartiles. Social support was measured by a four-question scale in Cycles 3 and 4 (1998/1999; 2000/2001);24 this score was dichotomised at the median, and change in social support was conceptualised as a change from high to low social support.

Statistical analyses

We performed two sets of analyses. First, among those with no history of major depression (unweighted n=7818), we assessed the onset of incident major depression comparing those with and without migraine at baseline; second, among those with no history of migraine (unweighted n=7765), we assessed the onset of incident migraine comparing those with and without major depression at baseline. Cox Proportional Hazards Models were fit, and HR and their 95% CI are presented. Models are presented as unadjusted; adjusting for sex and age; adjusting for sex, age and each stress exposure individually; and adjusting for sex, age and all stress exposures. Data analyses were completed using SAS 9.2 and SUDAAN 10.0.1. All estimates were weighted to adjust for unequal selection probabilities and cluster sampling; weights further adjust for attrition between the first and fourth cycles. SEs were calculated using the bootstrap method.

Results

Demographic information is presented in table 1. At baseline, 4.13%, 9.13% and 1.33% of the sample reported current depression only, migraine only and comorbid depression and migraine, respectively.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics ages 18–64, % (SE)

| Variable | Unweighted N | % (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 9342 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4986 | 50.31 (0.17) |

| Female | 4356 | 49.69 (0.17) |

| Age, mean (range) | 40.77 (18–64) | |

| Baseline migraine/depression comorbidity | ||

| None | 7619 | 85.41 (0.49) |

| Depression only | 404 | 4.13 (0.29) |

| Migraine only | 839 | 9.13 (0.40) |

| Depression and migraine | 124 | 1.33 (0.17) |

| Childhood trauma | ||

| 0 | 4194 | 49.61 (0.74) |

| 1 | 2265 | 25.82 (0.64) |

| 2+ | 2274 | 24.57 (0.65) |

| Recent marital change to divorced, separated or widowed | ||

| Yes | 214 | 2.47 (0.23) |

| No | 8781 | 97.53 (0.23) |

| Recent unemployment | ||

| Yes | 394 | 4.34 (0.32) |

| No | 8670 | 95.66 (0.32) |

| Recent change in social support | ||

| Yes | 1359 | 16.76 (0.60) |

| No | 6961 | 83.24 (0.60) |

| Years of follow-up | ||

| Median | 7.30 | |

| IQR | 6.29–7.67 |

Models for depression status predicting incident migraine are presented in table 2. Among non-migraineurs in Cycle 4 (2000/2001), 5.52% developed migraine during the 8-year follow-up. The sex- and age-adjusted model suggested that depression was predictive of incident migraine (HR: 1.62; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.53). When adjusting further for stressors in separate models, estimates were further attenuated; adjusting for chronic stress attenuated the estimate the most (HR: 1.34; 95% CI 0.84 to 2.13). When adjusting for all forms of stressors simultaneously, the depression–migraine estimate was attenuated to an HR of 1.30 (95% CI 0.80 to 2.10).

Table 2.

Adjusted HRs for depression predicting migraine, adjusting for various stressors, age and sex

| Model 1 (n=7076) | Model 2 (n=7076) | Model 3 (n=6678) | Model 4 (n=6868) | Model 5 (n=6953) | Model 6 (n=7064) | Model 7 (n=7044) | Model 8 (n=7076) | Model 9 (n=6339) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.85 (1.20–2.85) | 1.62 (1.03–2.53) | 1.59 (1.03–2.46) | 1.56 (0.98–2.47) | 1.61 (1.02–2.53) | 1.52 (0.97–2.38) | 1.34 (0.84–2.13) | 1.61 (1.02–2.54) | 1.30 (0.80–2.10) |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Childhood trauma | |||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 1 | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | 0.90 (0.60–1.33) | |||||||

| 2+ | 1.34 (1.00–1.79) | 1.09 (0.79–1.51) | |||||||

| Recent marital status change | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.54 (0.82–2.90) | 1.28 (0.59–2.75) | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Recent unemployment | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.00 (0.44–2.30) | 0.72 (0.29–1.78) | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Work stress | |||||||||

| 1st Quartile | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 2nd Quartile | 0.63 (0.42–0.95) | 0.61 (0.39–0.95) | |||||||

| 3rd Quartile | 0.66 (0.45–0.96) | 0.63 (0.41–0.96) | |||||||

| 4th Quartile | 0.89 (0.61–1.31) | 0.81 (0.52–1.27) | |||||||

| Chronic stress | |||||||||

| 1st Quartile | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 2nd Quartile | 0.91 (0.59–1.40) | 0.99 (0.63–1.56) | |||||||

| 3rd Quartile | 1.58 (1.11–2.25) | 1.64 (1.12–2.41) | |||||||

| 4th Quartile | 1.76 (1.22–2.53) | 1.68 (1.08–2.61) | |||||||

| Change in social support | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.77 (0.54–1.11) | 0.84 (0.58–1.21) | |||||||

| No | Reference | Refererence | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Female | 2.39 (1.83–3.12) | 2.34 (1.79–3.08) | 2.49 (1.90–3.26) | 2.44 (1.86–3.20) | 2.28 (1.73–2.99) | 2.39 (1.83–3.12) | 2.48 (1.89–3.25) | 2.32 (1.73–3.11) | |

| Age (continuous) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

Models for migraine status predicting incident depression are presented in table 3. Among subjects who had not had a depression up through Cycle 4 (2000/2001), 8.72% developed incident depression. Migraine status was predictive of incident depression in the age- and sex-adjusted model (HR: 1.55; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.08). Adjusting for stressors in separate models attenuated this relationship, with adjustment for chronic stress affecting the estimate the most (HR: 1.33; 95% CI 0.98 to 1.79). The fully adjusted model estimate for the migraine–depression HR was attenuated to 1.19 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.66).

Table 3.

Adjusted HRs for migraine predicting depression, adjusting for various stressors, age and sex

| Model 1 (n=7339) | Model 2 (n=7339) | Model 3 (n=6840) | Model 4 (n=7121) | Model 5 (n=7176) | Model 6 (n=7144) | Model 7 (n=7127) | Model 8 (n=7339) | Model 9 (n=6387) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migraine | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.84 (1.38–2.45) | 1.55 (1.15–2.08) | 1.43 (1.06–1.92) | 1.46 (1.08–1.98) | 1.54 (1.14–2.08) | 1.51 (1.11–2.05) | 1.33 (0.98–1.79) | 1.46 (1.07–1.99) | 1.19 (0.86–1.66) |

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Childhood trauma | |||||||||

| None | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 1 | 1.23 (0.92–1.64) | 1.14 (0.84–1.55) | |||||||

| 2+ | 2.36 (1.79–3.12) | 1.89 (1.38–2.59) | |||||||

| Recent marital status change | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.91 (0.40–2.06) | 0.78 (0.33–1.84) | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Recent Unemployed | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.52 (0.93–2.49) | 1.16 (0.68–1.99) | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Work stress | |||||||||

| 1st Quartile | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 2nd Quartile | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | 0.70 (0.52–0.95) | |||||||

| 3rd Quartile | 0.69 (0.50–0.94) | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | |||||||

| 4th Quartile | 1.12 (0.84–1.51) | 1.06 (0.77–1.48) | |||||||

| Chronic stress | |||||||||

| 1st Quartile | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| 2nd Quartile | 1.45 (1.06–2.00) | 1.47 (1.03–2.08) | |||||||

| 3rd Quartile | 2.02 (1.50–2.73) | 1.89 (1.37–2.62) | |||||||

| 4th Quartile | 2.93 (2.20–3.88) | 2.49 (1.80–3.44) | |||||||

| Change in social support | |||||||||

| Yes | 0.91 (0.69–1.20) | 0.94 (0.71–1.23) | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Female | 1.91 (1.52–2.39) | 1.86 (1.49–2.34) | 1.94 (1.55–2.44) | 1.92 (1.53–2.41) | 1.80 (1.43–2.27) | 1.89 (1.50–2.37) | 1.89 (1.50–2.39) | 1.83 (1.43–2.34) | |

| Age (continuous) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

Discussion

Without considering common causes or other explanations, these results align with earlier findings supporting a bidirectionality to a migraine–depression association: in crude analyses, migraine status predicted incident depression, and depression status predicted incident migraine. However, both directions of this relationship are largely explained by stressors that likely increase risk for both migraine and depression: adjusting for all measured forms of stress in these surveys attenuated each estimate considerably (estimates decreased from 1.62 to 1.30 and 1.55 to 1.19) and the associations were no longer significant after adjustment. Implications for research as well as clinical and public-health practices are discussed.

Importantly, all stressors studied here did attenuate the results, suggesting that any form of stress may be an important common cause to consider when studying migraine and depression. This finding follows from prior research that supports both acute and chronic forms of stress as being confounders, since these have been shown to predict depression and migraine.10 17–21 The present study suggests that these stressors collectively explain much of the perceived migraine–depression association; research that does not account for these common causes when studying depression and migraine may be presenting misleading estimates. The perceived migraine–depression associations presented in many prior studies may be largely explained by unmeasured confounding by such types of stressors. The magnitude of confounding due to each specific stressor is dependent on several factors, including the strength of the covariate–exposure association, the strength of the covariate–outcome association and the prevalence of the covariate. Our measure of chronic stress was strongly predictive of both migraine and depression onsets, as well as associated with these disorders at baseline, and thus was the strongest risk factor considered in the present analyses. On the other hand, recent changes in employment and marital status were relatively rare life events, and were not strongly predictive of these disorders, so the magnitude of attenuation when considering each of these variables was minor. Optimally, future studies of migraine and depression would assess all potential confounders; as this is not always feasible, investigators may consider prioritising assessing chronic stress over some of these other stressors, and accompany results with sensitivity or bias analyses for any stressors that remained unmeasured.

Our finding that chronic stress was the strongest stress-related risk factor fits into the broader context of research, suggesting that chronic stress may be causative of various types of chronic pain and major depression. In disentangling the relationship between depression, chronic stress and chronic pain such as fibromyalgia, it has been proposed that chronic stress may lead to dysfunction in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which in turn could lead to both depression and some forms of chronic pain.25 Research specific to stress and migraine supports this biological theory.26 Notably, childhood trauma was a strong risk factor in migraine predicting depression; as many of the types of trauma assessed were chronic in nature, this aligns with the finding that perhaps chronic forms of stress are especially potent common causes of migraine and depression.

Although certainly some of the crude association between depression and migraine may still be explained by genetics, other common causes and/or biological pathways between the two disorders, the current findings suggest interesting considerations when developing future intervention strategies. Given the possibility of a biological mechanism between these two disorders, much research attention has been focused on the efficacy of antidepressant medications on preventing and managing migraine, with mixed success.27–29 However, the current study suggests that perhaps a primary strategy could target reducing stress, particularly chronic stress, as this may both reduce the burden of the index disorder as well as potentially prevent the second condition from occurring. Indeed, there have been studies showing that various behavioural or stress management therapies (eg, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy) are effective treatments for migraine, supporting one aspect of this hypothesis.30–32 Given how much chronic stress and other stressors seem to explain the comorbidity, such a strategy may have the potential for reducing this comorbidity burden on a larger scale than some of these other postulated pharmacological strategies, although further research actually comparing such treatment strategies would be needed. Utilising a stress-reducing strategy to address this comorbidity assumes that stress is (directly or indirectly) causative of both disorders, while it is possible that stress is a risk factor through associations with a common cause.

The study has numerous strengths. This is one of only a few studies to prospectively assess the migraine–depression comorbidity bidirectionally,1 2 10 and extends these previous findings by examining whether a rich assortment of widely used stress measures explained the associations found. The nationally representative nature of the study aids the generalisability of these findings, and the sample size and length of follow-up are exceptional.

However, certain limitations warrant consideration. Migraine was assessed as only a single, self-reported question at each cycle. Self-reported symptom-based assessments do generally report a higher prevalence than doctor diagnoses;33 the assessment in the NPHS inquires about diagnosis by a health professional which may offset some of this over-reporting, but certainly misclassification may still be an issue. Specifically, self-report may be further inflated in depressed individuals, which may actually contribute to some overestimation in our associations. While the measure of major depression (CIDI-SFMD) has demonstrated psychometric properties,22 34 35 the 12-month diagnosis (which thus does not cover the 2 years between each study assessment) hinders inference about the history of major depression, possible episodes unmeasured in the gap years of the study and actual timing of onset of the disorder; subjects who have less frequent depressive episodes or episodes that are shorter in duration would be less likely to be measured accurately. However, by using an interim cycle as ‘baseline’, we were able to construct over a half-decade profile of subjects’ ‘history’ of major depression to diminish the issue regarding assessing history. Finally, we did not have complete follow-up for all subjects. Weighting was used to correct for attrition between Cycles 1 and 4. From Cycle 4 through 8 the majority of subjects were assessed 8 years later (see figure 1), and follow-up duration was not associated with migraine or depression status at baseline. Follow-up duration, however, was associated with age and a few stressors (greater chronic stress, recent unemployment and recent divorce were associated with shorter follow-up; p's<0.05); however, as stress likely predicts higher levels of the outcome disorders, it is likely this implies that some subjects were censored prior to the onset of the outcome, meaning that stress would explain even more of the association measured had complete follow-up occurred.

These analyses highlight considerations for future research. These analyses represent a rich assortment of stressors, but several other stressors may also merit examination, for example, childhood sexual abuse, acute recent traumas such as injury or illness, etc. Further, as some of the stressors were only assessed in one or two cycles, we were not able to fully address the time-varying nature of the relationships between stress and these episodic conditions. Given that we found recent and prior stress to be relevant in this comorbidity, future research may wish to more closely examine the time-varying relationship between stress and these two conditions individually and comorbidly. Specifically, while stress is a risk factor for both disorders, it may also be caused by each disorder, and thus assessing temporal relationships using models that account for time-varying confounding appropriately (eg, marginal structural models) may highlight the relationship between these variables further.

Understanding the causal mechanisms underlying the migraine–depression comorbidity may have a major public health impact. Major depression is a chief cause of disability worldwide,36 estimated by the WHO to become the second leading cause of disease burden by the year 2020.37 Meanwhile, migraine affects 11% of the adult population, and when combined with other headache disorders also makes it into the top 10 causes of disability by WHO estimates.38 Moreover, studies suggest that the disability and burden of these disorders may be compounded when present together;5 disease severity appears greater when these disorders are comorbid, for example, frequency and duration of migraine attacks have a significant association with psychiatric comorbidity.39 Migraine patients with a psychiatric disorder report generally a lower quality of life than other migraine patients;8 in parallel, depression patients who report migraine also report poorer quality of life compared with other depression patients.40 As such, implementation of effective stress-management strategies for migraineurs and those suffering from depression (as well as similar strategies to prevent the index disorder onset) may have major implications for prevention and intervention strategies that may lower the societal costs and burdens of both disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Irene Wong of Statistics Canada for her assistance with data access and use. The research and analysis are based on data from Statistics Canada and the opinions expressed do not represent the views of Statistics Canada.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS and IC conceived and designed the study and interpreted the results. SS, YZ and MW performed the data analysis. SS wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs programme for Dr Colman. Funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: A statement like this might be appropriate: “Data for this study are from the National Population Health Survey, a longitudinal cohort study directed by Statistics Canada. Data are accessible through Statistics Canada’s Research Data Centre programme (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/rdc-cdr/index-eng.htm).

References

- 1.Breslau N, Lipton RB, Stewart WF, et al. Comorbidity of migraine and depression: investigating potential etiology and prognosis. Neurology 2003;60:1308–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breslau N, Schultz LR, Stewart WF, et al. Headache and major depression: is the association specific to migraine? Neurology 2000;54:308–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camarda C, Pipia C, Taglialavori A, et al. Comorbidity between depressive symptoms and migraine: preliminary data from the Zabut Aging Project. Neurol Sci 2008;29(Suppl 1):S149–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung CI, Liu CY, Cheng YT, et al. Migraine: a missing link between somatic symptoms and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2009;117:108–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jette N, Patten S, Williams J, et al. Comorbidity of migraine and psychiatric disorders—a national population-based study. Headache 2008;48:501–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kececi H, Dener S, Analan E. Co-morbidity of migraine and major depression in the Turkish population. Cephalalgia 2003;23:271–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanteri-Minet M, Valade D, Geraud G, et al. Migraine and probable migraine—results of FRAMIG 3, a French nationwide survey carried out according to the 2004 IHS classification. Cephalalgia 2005;25:1146–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Kolodner KB, et al. Migraine, quality of life, and depression: a population-based case-control study. Neurology 2000;55:629–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McWilliams LA, Goodwin RD, Cox BJ. Depression and anxiety associated with three pain conditions: results from a nationally representative sample. Pain 2004;111:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modgill G, Jette N, Wang JL, et al. A population-based longitudinal community study of major depression and migraine. Headache 2012;52:422–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molgat CV, Patten SB. Comorbidity of major depression and migraine—a Canadian population-based study. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:832–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratcliffe GE, Enns MW, Jacobi F, et al. The relationship between migraine and mental disorders in a population-based sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhee H. Prevalence and predictors of headaches in US adolescents. Headache 2000;40:528–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samaan Z, Farmer A, Craddock N, et al. Migraine in recurrent depression: case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:350–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang SJ, Liu HC, Fuh JL, et al. Comorbidity of headaches and depression in the elderly. Pain 1999;82:239–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antonaci F, Nappi G, Galli F, et al. Migraine and psychiatric comorbidity: a review of clinical findings. J Headache Pain 2011;12:115–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colman I, Garad Y, Zeng Y, et al. Stress and development of depression and heavy drinking in adulthood: moderating effects of childhood trauma. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:265–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le H, Tfelt-Hansen P, Skytthe A, et al. Association between migraine, lifestyle and socioeconomic factors: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Headache Pain 2011;12:157–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, et al. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:103–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maleki N, Becerra L, Borsook D. Migraine: maladaptive brain responses to stress. Headache 2012;52(Suppl 2):102–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risch N, Herrell R, Lehner T, et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;301:2462–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek DK, et al. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1998;7:171–85 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotton C. Recent developments in the low income cut offs. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Canada National Population Health Survey Cycle 1 (1994–1995). Public use microdata files documentation. Ottawa, 1995

- 25.Blackburn-Munro G. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction as a contributory factor to chronic pain and depression. Curr Pain Headache Rep [Review] 2004;8:116–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sauro KM, Becker WJ. The stress and migraine interaction. Headache 2009;49:1378–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache 2000;40:572–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheftell FD, Atlas SJ. Migraine and psychiatric comorbidity: from theory and hypotheses to clinical application. Headache 2002;42:934–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silberstein SD, Goadsby PJ. Migraine: preventive treatment. Cephalalgia 2002;22:491–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin PR, Forsyth MR, Reece J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus temporal pulse amplitude biofeedback training for recurrent headache. Behav Ther 2007;38:350–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penzien DB. Stress management for migraine: recent research and commentary. Headache 2009;49:1395–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rains JC, Penzien DB, McCrory DC, et al. Behavioral headache treatment: history, review of the empirical literature, and methodological critique. Headache 2005;45(Suppl 2):S92–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cousins G, Hijazze S, Van de Laar FA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the ID migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache 2011;51:1140–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patten SB. Performance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form for major depression in community and clinical samples. Chronic Dis Can 1997;18:109–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patten SB, Brandon-Christie J, Devji J, et al. Performance of the composite international diagnostic interview short form for major depression in a community sample. Chronic Dis Can 2000;21:68–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ustun TB, Kessler RC. Global burden of depressive disorders: the issue of duration. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:181–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon GE. Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:208–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007;27:193–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitsikostas DD, Thomas AM. Comorbidity of headache and depressive disorders. Cephalalgia 1999;19:211–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hung CI, Wang SJ, Hsu KH, et al. Risk factors associated with migraine or chronic daily headache in out-patients with major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:310–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.