Abstract

Objective

To determine whether elevated blood cobalt (Co) concentrations are associated with early failure of metal-on-metal (MoM) hip resurfacings secondary to adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD).

Design

Cohort study.

Setting

Single centre orthopaedic unit.

Participants

Following the identification of complications potentially related to metal wear debris, a blood metal ion screening programme was instigated at our unit in 2007 for all patients with Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) and Birmingham MoM hip resurfacings. Patients were followed annually unless symptoms presented earlier. Symptomatic patients were investigated with ultrasound scan and joint aspiration. The clinical course of all 278 patients with ‘no pain’ or ‘slight/occasional’ pain and a Harris Hip Score greater than or equal to 95 at the time of venesection were documented. A retrospective analysis was subsequently conducted using mixed effect modelling to investigate the temporal pattern of blood Co levels in the patients and survival analysis to investigate the potential role of case demographics and blood Co levels as risk factors for subsequent failure secondary to ARMD.

Results

Blood Co concentration was a positive and significant risk factor (z=8.44, p=2×10–16) for joint failure, as was the device, where the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing posed a significantly reduced risk for revision by 89% (z=−3.445, p=0.00005 (95% CI on risk 62 to 97)). Analysis using Cox-proportional hazards models indicated that men had a 66% lower risk of joint failure than women (z=−2.29419, p=0.0218, (95% CI on risk reduction 23 to 89)).

Conclusions

The results suggest that elevated blood metal ion concentrations are associated with early failure of MoM devices secondary to adverse reactions to metal debris. Co concentrations greater than 20 µg/l are frequently associated with metal staining of tissues and the development of osteolysis. Development of soft tissue damage appears to be more complex with females and patients with ASR devices seemingly more at risk when exposed to equivalent doses of metal debris.

Keywords: Orthopaedic & Trauma Surgery

Article summary.

Article focus

Current Food and Drug Administration guidance for the management of patients with MoM hips states that ‘the utility of routine screening of asymptomatic patients using blood metal ion testing has not been established.’

This study sought to document the clinical course of asymptomatic patients with elevated blood cobalt (Co) concentrations.

Key messages

Elevated blood Co concentrations were associated with an increased probability of early joint failure secondary to the development of an adverse local tissue response.

Male patients with low Co concentrations had a very low incidence of adverse tissue reactions and rationalisation of resources with regard to follow-up and repeat blood samples in this group may be considered.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study is the first to describe the clinical course of patients following their initial blood metal ion results. It includes three times the number of subjects as the research on which the current Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidance is based.

The time at which blood samples were taken postoperatively was not standardised.

Background

Modern metal-on-metal (MoM) hip resurfacing was developed in order to address the relatively poor survival of conventional prostheses in young, active male patients.1 Several clinical studies have now shown extremely encouraging survivorship, negligible dislocation rates and excellent functional outcome scores in this patient group.2 3 All materials used in hip arthroplasty, however, have their disadvantages. With MoM prostheses, it is the release of cobalt (Co) and chromium (Cr) metal debris from the components.4 Adverse reactions to metal debris (ARMD) have captured a lot of media attention recently but fluid collections and soft tissue damage were noted in the presence of increased hip joint fluid Co concentrations as early as 1975.5 These complications were documented in a report involving patients who had received one of the so-called ‘first generation’ MoM hips, the Mckee. Thirty-five years on, we showed a significant increase in the wear rates of explanted fourth generation MoM hip components which had failed secondary to ARMD compared with control specimens.6 These findings were substantiated by Glyn-Jones et al7 in their studies on pseudotumour development.

Blood and serum Cr and Co concentrations are reliable indicators of wear rates in hip resurfacing arthroplasty.8 9 The relationship between metal ion concentrations and the development of soft tissue necrosis and osteolysis is not straightforward, however. We have previously examined the extent of local tissue damage in relation to blood and hip joint fluid ion concentrations and compared them with the wear rates of the corresponding retrieved components.10 While no patient was found to have developed a significant soft tissue reaction with a well-functioning bearing surface, in patients who did experience ARMD-related failure, the extent of soft tissue damage did not appear to be dose related to metal debris exposure. The overall results suggested that the observed soft tissue necrosis was the result of the development of a negative immune cascade which varied between patients.10

It is quite likely that patients exposed to increased metal debris may show temporary ‘tolerance’ to the stimulus and a certain time period must elapse or a threshold exposure be reached before an immune response is established and symptoms develop. Several publications include descriptions of patients who were initially pain-free but went on to develop pain a number of years later.6 11 Furthermore, the increased metal ion levels in asymptomatic patients may be associated with underlying pathology, including osteolysis.10 12 It is well recognised that osteolysis can be silent, often only manifesting in the form of radiographic changes or pain secondary to a loosening of components.

These observations challenge recent Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) guidance, which does not recommend that patients with MoM hip resurfacing arthroplasties should undergo routine blood metal ion testing in the absence of symptoms ‘unless the patient cohort is of concern’. It states that a Cr or Co level greater than 7 µg/l ‘indicates the potential for soft tissue reaction.’13 But this guidance was primarily based on a cross-sectional study which compared patients with failed MoM hips to control patients with ‘well-functioning’ MoM hips.14 This study included asymptomatic patients with elevated blood metal ion levels in the ‘well-functioning’ control group. In fact, several patients assigned to the ‘well-functioning’ hip group had blood Co concentrations in excess of 5 µg/l and one was in excess of 50 µg/l. These patients then acted as the control group to determine whether blood metal ion testing was legitimate to identify problems in clinical practice. The postoperative time at which samples were taken was not controlled for, and nor was an attempt made to compensate for time as a confounding factor. Blood metal ion testing provides the surgeon with a clinical assessment of the performance of the prosthetic joint.8 9 We believe that the performance of the joint in a tribological sense should be included in the consideration of ‘well-functioning controls’ and some consideration should be given to the effect of exposure to high concentrations of metal debris over time.

To date, no studies thus far have documented the clinical course of asymptomatic patients with elevated blood metal ion concentrations. The aim of this piece of work was to address this deficiency.

Patients and methods

The senior author (AVFN) is a lower limb arthroplasty surgeon with extensive experience in MoM hip resurfacing arthroplasty. AVFN originally used the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing ((BHR), Smith and Nephew, Warwick, UK) from 2002, but in April 2004 he began to use the Articular Surface Replacement (ASR, Depuy, Leeds, UK) exclusively. Our previously published work has described in detail the clinical and radiological outcomes of these ASR and BHR patient cohorts as well as identifying the variables leading to excessive metal ion release into the blood.6 In 2007, after we had observed a number of unusual tissue reactions in patients implanted with the ASR device at our centre, a clinical review and blood metal ion screening programme was started for all patients with MoM resurfacing hips under AVFN's care. During these review appointments, Harris Hip and UCLA activity scores are documented. Patients are currently reviewed at a maximum of 12 months between appointments and blood tests are repeated.

This paper documents the clinical course of all patients who gave a blood sample between 2007 and 2010 who had no or ‘slight’ pain, no radiological abnormalities and a Harris Hip Score15 greater than or equal to 95 at the time of venesection. All patients therefore underwent a clinical review at a minimum of 2-year postvenesection. As blood metal ion testing and close follow-up of MoM hip patients have been routine at our centre since 2007, no ethical approval was required for this retrospective audit.

Revision surgery for ARMD

We have described ARMD in detail in our previous work.10 16 The diagnosis is made on the combination of clinical history, findings at revision and histological analysis of tissue retrieved at revision surgery. Reactions to metal debris are typically characterised by a combination of revision findings which include: soft tissue lesions, which can be catastrophic and involve local neurovascular structures; the presence of abnormal (sterile) fluid, which can be copious and pus-like in nature; acetabular and/or femoral osteolysis associated with macroscopic deposition of metal (metallosis). At revision surgery the macroscopic appearance of the tissues was scored by the attending surgeon using a simple grading system10: 0, no soft tissue necrosis; 1, small, localised areas of (mild) tissue necrosis; 2, widespread (moderate) tissue necrosis, stability of the implant not obviously compromised and 3, widespread (severe) tissue necrosis with compromised stability of the implant. The tissues retrieved at revision also underwent a semiquantitative analysis by one consultant histopathologist with extensive experience in this area. For this paper, the cellular response was categorised as ‘histiocytic’, ‘lymphocytic/aseptic lymphocyte dominated vasculitis associated lesion (ALVAL)’ dominant or ‘mixed’ as described in our previous work.10 In order to categorise patients and provide context to the findings at revision, we divided the patients into subgroups according to the results of our work examining the relationship between wear rates of explanted prostheses and pre-revision blood metal ion analysis.8 These subdivisions are described in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| <1 (low wear) | 1–2 (low/expected wear) | 2–5 (equivocal) | 5–10 (increased wear) | >10 (excessive wear) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 57 | 95 | 76 | 25 | 46 |

| Number of BHR hips | 4 | 29 | 12 | 2 | 6 |

| Time from op to venesection | 49 (44–52) | 52 (44–68) | 52 (42–68) | 55 (52–58) | 54 (42–68) |

| Number of ASR hips | 53 | 66 | 64 | 23 | 39 |

| Time from op to venesection | 30 (4–67) | 28 (7–62) | 33 (12–73) | 30 (12–67) | 34 (12–70) |

| Mean age at primary (range) | 55 (28–78) | 55 (28–73) | 57 (39–78) | 59 (45–69) | 54 (35–68) |

| Number of female hips (%) | 15 (26.3) | 29 (30.5) | 26 (33.8) | 15 (62.5) | 18 (43.9) |

| Number (%) of hips revised for ARMD within 9 years of surgery | 0 | 1 (1.1) | 4 (5.3) | 5 (20.0) | 30 (65.2) |

The patients have been subdivided according to the classifications described in table 2.

ARMD, adverse reaction to metal debris; ASR, Articular Surface Replacement; BHR, Birmingham Hip Resurfacing.

Table 2.

Subdivisions according to cobalt (Co) concentrations

| Cobalt range (µg/l) | |

|---|---|

| <1 | Optimally functioning joints. Co concentrations in the range of normal physiological values |

| 1–2 | ‘Normal/expected wear’ and the majority of published studies involving well-functioning hip resurfacing devices report median Co levels in this range31 32 |

| 2–5 | ‘Equivocal wear’. The significance of Co concentrations in this range are not currently well understood |

| 5–10 | ‘Increased wear’. A Co concentration ≥5 µg/l is highly sensitive and specific for increased wear of explanted components8 |

| >10 | ‘Excessive wear’. In a healthy individual, Co concentrations >10 µg/l signify unequivocally high rates of wear8 |

Data analysis

Event analysis of hip failure

A statistical model was created to examine the relationship between a patient's initial recorded blood Co concentration and the risk of the development of joint failure secondary to an adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD). For the purposes of the prosthetic survival analysis, the endpoints were: the last documented clinical review; the patient undergoing revision surgery prior to March 2012 for any reason other than ARMD; or patient death. Individuals were censored if they had undergone revision surgery for ARMD. Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for the two parts of the study

| Patient inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Event analysis of hip failure | |

| ASR or BHR implanted by AVFN | No other MoM hip replacements |

| Blood Co concentration recorded post hip resurfacing | (no patients were excluded for renal function abnormalities) |

| Clinical review at a minimum of 2-year postblood test | |

| Normal basic renal function test at the time of Co blood test (urea and creatinine) | |

| Harris hip score ≥95 | |

| Mixed effects modelling of trends in blood Co | |

| All patients in the study who had given repeat blood samples from 2007–2012 with MoM hip resurfacings remaining in situ | Patients found to have developed abnormal renal function tests |

ASR, Articular Surface Replacement; BHR, Birmingham Hip Resurfacing; Co, cobalt; MoM, metal-on-metal.

We used Cox-proportional hazards models to investigate risk factors for failure secondary to ARMD following the hip resurfacing procedure. The Cox model assumes that there is an underlying unspecified baseline hazard that stays constant through time, that is, influenced by covariates that mitigate or enhance the risk of an event. Our hypothesis was that the size17 and type of the device,18 patient age,19 sex19 and blood Co levels were associated with an enhanced risk of hip failure. The Cox model assumes that the hazard of the event remains fixed through time, that is, the effect of the individual covariates remains the same and proportional. We investigated non-proportionality in our models by plotting the Schoenfeld residuals and by correlating the residuals for each model with time for each covariate with a two-sided χ2 test. All models were fitted following the methodolody of Therneau and Grambsch.20 We then used the best-fitting model to predict the most likely individual survival curves of MoM devices for men and women at three levels of blood Co (2, 5 and 10 μg/l), to illustrate the association between revision and blood Co.

Mixed effects modelling of trends in blood Co

In order to examine the legitimacy of using the single initial blood Co result in the survival analysis, all available repeated Co results from single patients were collected (table 3). As blood samples were taken at different times postoperatively as repeated measures, a generalised linear mixed effect model (GLMM) was used to investigate the extent to which blood Co levels changed in relation to the time since the original hip replacement operation, with patient age and sex, the device used and bearing diameter of the implant as explanatory variables. Our hypothesis was that blood Co levels would increase with time since the operation, would differ between males and females and be independent of patient age. We hypothesised that the size of the implant would also impact on the levels of Co because smaller implants are known to wear (and hence release Co) more readily than larger ones.17 We adopted a progressive model building strategy following Pinheiro and Bates,21 first assessing the impact of all variables without the inclusion of random effects and then extending to include random effects and an autoregressive correlation structures as appropriate to allow for any autocorrelation in the response.

Results

There were a total of 299 resurfacings in 278 patients. Of these, there were 246 ASRs and 53 BHR prostheses. Patient demographics can be seen in table 1. The mean (range) postoperative follow-up of the patients was 70 months (12–118). The mean (range) follow-up postvenesection was 36 months (2–63). Two patients died in the study period of unrelated causes.

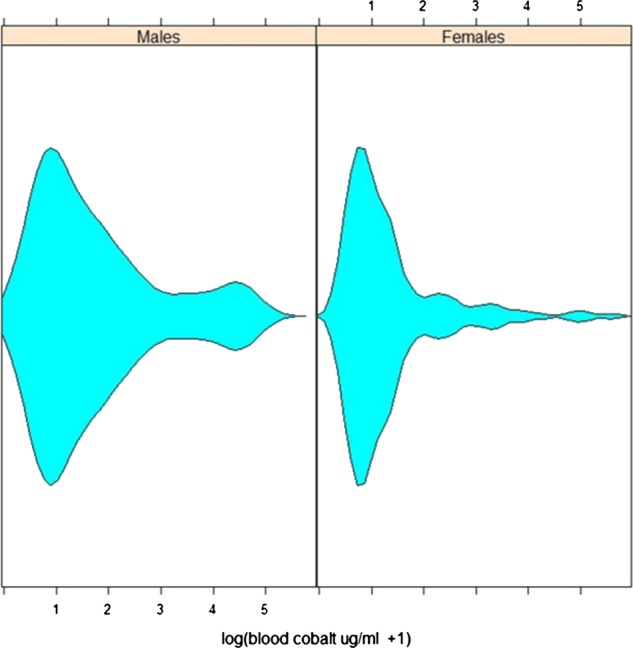

Mixed effect modelling of trends in blood Co

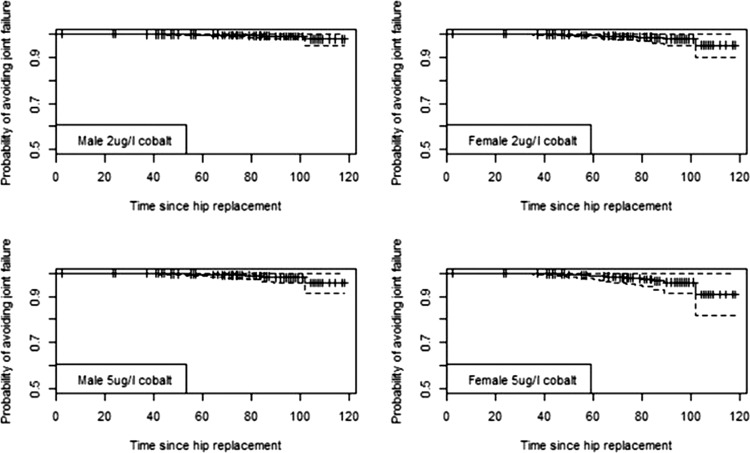

In total, 205 patients gave repeat samples at a mean (range) of 27.3 months (6–52) following the initial test. Fifty-seven of these patients gave a third sample at a mean (range) of 10.6 months (6–21) following the second test. Blood Co concentrations were skewed to the right with a few patients having very high blood levels at all sampling points. The distribution appeared to be multimodal in both sexes (figure 1). Log transformed levels of blood Co in patients were not related to time since surgery (t=0.3291 p=0.7423); the type of device used (t=−1.225, p=0.2220), patient age (t=−0.1351, p=0.8926) or the size of the device used (t=−0.3084, p=0.7480) in the full model analysing trends through time. There was a suggestion that male sex was associated with reduced Co concentrations; patient sex (−1.967, p=0.0502). Simplification to a model with sex as the only explanatory variable suggested that there was some evidence that men had lower blood Co level than women (t=−2.240, p=0.0259) of analysis of log-transformed blood Co levels. The SD of the random effect for patient factors was 73% of the unexplained variation in the model, indicating that there was a large component of unmeasured variation attributable to the patient. Inclusion of an autoregressive correlation structure in the model gave a marginally better model than one in which it was not included (L.ratio=3.737, p=0.0532).

Figure 1.

Violin plot showing distribution blood cobalt concentrations in men and women.

As the measured Co concentration was not significantly related to time from surgery to blood, it was assumed to be legitimate to conduct survival analysis using the first sample for the patients with time from surgery to most recent follow-up/death/revision used in the analysis.

Revision cases

At the time of the writing, 41 joints had been revised (36 ASRs and 5 BHRs). All but one of these prostheses (an ASR revised secondary to avascular necrosis in a male patient) were revised secondary to ARMD. Only 25 of the ARMD prostheses were revised in female patients and 15 in male patients. Table 4 includes the modes of presentation of these patients.

Table 4.

Details of the revision cases in the study

| Signs and symptoms | Male:female | Moderate/severe soft tissue destruction (%) | Osteolysis (%) | Percentage of ALVAL or mixed response (percentage of lymphoid neogenesis) | Median (range) (blood Co) (µg/l) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n=21) | |||||

| Increasing pain and moderate large fluid effusion | 5:16 | 47 | 81 | 71 (43) | 17.8 (4.60–109.7) |

| Group 2 (n=11) | |||||

| Pain with small fluid effusion | 5:6 | 18 | 55 | 18 (0) | 23.3 (1.37–147) |

| Group 3 (n=4) | |||||

| Acute pain with femoral collapse | 3:1 | 0 | 100 | 25 (0) | 49.8 (12.0–271.0) |

| Group 4 (n=4) | |||||

| Minor discomfort and grossly elevated ions with mass (n=1) grinding sensation (n=1), gross femoral neck thinning (n=1), squeaking (n=1) | 3:1 | 50 | 75 | 50 (50) | 81.8 (11.6–164) |

| Avascular necrosis (non ARMD) (n=1) | 1:0 | 0 | 0 | Histiocytic | 1.90 |

ARMD, adverse reaction to metal debris; ALVAL, aseptic lymphocyte dominated vasculitis associated lesion; Co, cobalt.

Event analysis of hip replacement failure

As only two patients died during the course of the study, the impacts of competing risks were assumed to be negligible. Analysis of hip resurfacing failure using Cox-proportional hazards models indicated that men had a 66% lower risk of joint failure than women (z=−2.29419, p=0.0218, (95% CI on risk reduction 23 to 89)). Inclusion of time since blood sample as a variable showed that it was not an important risk factor for failure (t=−1.454, p=0.1459). The level of blood Co (as a log transformed variable) was a positive and significant risk factor (z=8.44, p=2 × 10−16), as was the device, where the BHR posed a significantly reduced risk for revision by 89% (z=−3.445, p=0.00005, (95% CI on risk 62 to 97)). An analysis of the Schoenfeld residuals for the model with only the significant variables model showed that the assumption of proportionality of hazard for this model were met (log(Co+1), χ2=8.72, p=0.350; sex, χ2=3.139, p=0.077 and device, χ2=1.591, p=0.207). Risk of failure was highest for females fitted with ASR and a high blood Co level, with the risk of avoiding failure dropping to zero after 10 years, suggesting that hip failure would be inevitable for a person with this set of characteristics. In contrast, failure was least likely for males fitted with the BHR device with low levels of blood Co for which the risk of failure was of the order of 5% over 10 years.

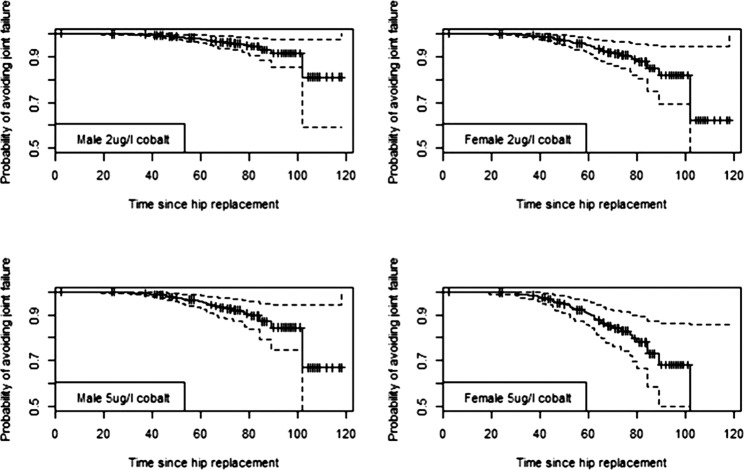

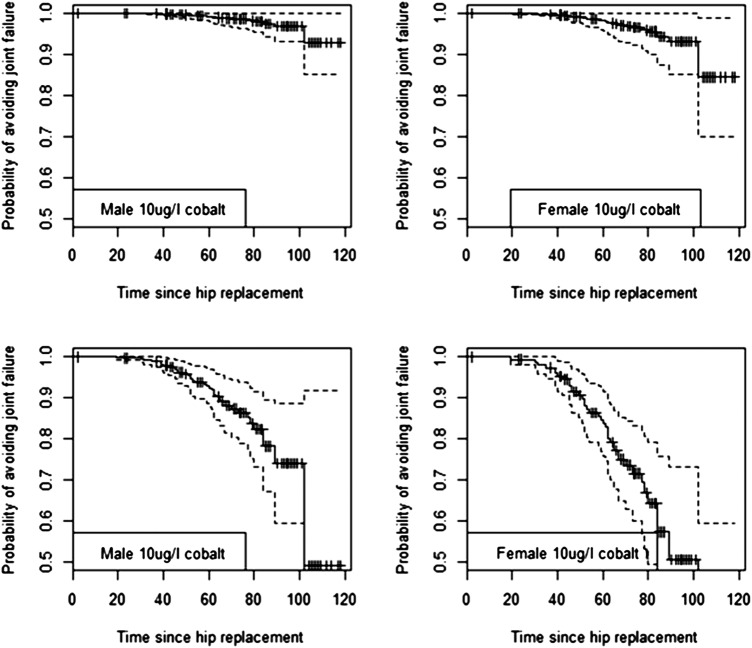

Predicted survival

We used the outputs from the best-fit Cox models identified in the event analysis to generate predicted survival curves for individual patients with certain characteristics. We then used the curves to predict the probability of avoiding revision at 5 and 7 years with associated CIs generated from the regression equations. Predicted survival curves of the replacement for men and women with blood Co concentrations of 2, 5 and 10 μg/l (figures 2–4 and table 5) illustrate the increased risk if the case was a woman, fitted with an ASR device and had elevated blood concentrations of Co. As an example, a woman with an ASR and 10 μg/l of Co in her blood has a 57.3% chance of avoiding revision by 7 year post primary replacement, while a man has a risk of 78.2%. Equivalent probabilities for BHR women and men with the same Co levels at 7 years are 94.2% and 97.4%, respectively. These indicate the increased risk of revision with ASR and high levels of Co.

Figure 2.

Predicted survival curves for hip replacements for two male and two female hypothetical individuals with different levels of blood cobalt at 2 and 5 µg/l. Device is the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing. Time period is in months. Survival curves shown with 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Predicted survival curves for hip replacements for two male and two female hypothetical individuals with different levels of blood cobalt of 2 and 5 µg/l. Device is the Articular Surface Replacement. Time period is in months. Survival curves shown with 95% CI.

Figure 4.

Predicted survival curves for hip replacements for two male and two female hypothetical individuals with blood cobalt concentrations of 10 µg/l. Device is the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (top two plots) and Articular Surface Replacement (bottom two plots). Time period is in months. Survival curves shown with 95% CI.

Table 5.

Predicted probabilities of risk of avoiding revision for patients with different blood Co concentrations 5 and 7 years after initial intervention

| Cobalt (µg/l) | Males |

Females |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability | Lower CI | Upper CI | Probability | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

| Probability of avoiding ARMD at 5 years | ||||||

| BHR | ||||||

| 2 | 99.7 | 99.3 | 100 | 99.4 | 98.6 | 100 |

| 5 | 99.5 | 98.8 | 100 | 98.9 | 97.5 | 100 |

| 10 | 99.1 | 97.9 | 100 | 98.1 | 95.7 | 100 |

| ASR | ||||||

| 2 | 99.7 | 99.3 | 100 | 99.4 | 98.6 | 100 |

| 5 | 99.5 | 98.4 | 100 | 99.0 | 97.6 | 100 |

| 10 | 87.8 | 92.4 | 97 | 83.7 | 75.8 | 91.6 |

| Probability of avoiding ARMD at 7 years | ||||||

| BHR | ||||||

| 2 | 99.2 | 98.1 | 100 | 98.2 | 96 | 100 |

| 5 | 98.4 | 96.5 | 100 | 96.7 | 92.6 | 100 |

| 10 | 97.4 | 94.1 | 100 | 94.2 | 87.5 | 100 |

| ASR | ||||||

| 2 | 99.2 | 98.1 | 100 | 98.2 | 96.0 | 100 |

| 5 | 98.4 | 96.5 | 100 | 96.7 | 92.6 | 100 |

| 10 | 78.2 | 67.0 | 91.5 | 57.3 | 38.8 | 75.8 |

ARMD, adverse reaction to metal debris; ASR, Articular Surface Replacement; BHR, Birmingham Hip Resurfacing.

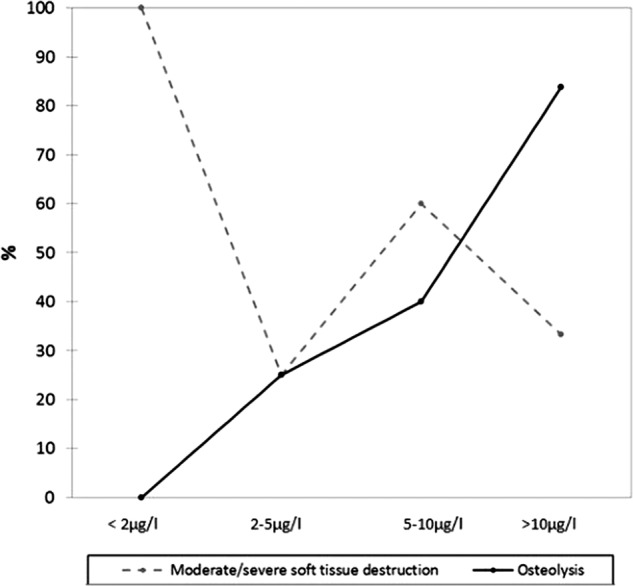

Figure 5.

The incidence of osteolysis and/or moderate/severe soft tissue destruction at revision surgery. Patients have been grouped according to their preoperative blood result.

Discussion

This paper examines the association between elevated blood metal ion concentrations and early failure of hip resurfacing devices due to local ARMD in asymptomatic patients. It provides the first evidence that blood metal ion tests can be used as a clinical indicator of the risk of early joint failure in asymptomatic patients.

The main weakness of the paper was the lack of standardisation of the time at which blood samples were taken postoperatively. This was because the work was carried out not as a piece of research but rather one of clinical need as more and more problems began to emerge with the ASR device. To analyse the effect of this variation in time from primary surgery to sampling, a GLMM was constructed. We were able to do this because a large number of patients had undergone repeat sampling at a mean of 2 years. No significant temporal variation was seen, with the implication being that, on average, very low levels tended to stay low and elevated levels remained high.

No preoperative blood samples were taken, although we do not accept that this was a significant limitation. A recent unpublished study involving 3042 healthy volunteers at the nearby regional blood transfusion centre showed that the median (first and third quartiles) blood concentration of Co was 0.5 µg/l (0.4 to 0.6). Only 0.46% of the concentrations were found to be above 1.5 µg/l and in only one sample (0.03%) was the Co concentration above 2 µg/l.

The results of the current study suggest that elevated blood Co levels are a matter of concern, even in asymptomatic patients. Female patients appear to be at greater risk of joint failure than male patients with equivalent Co concentrations, particularly at lower levels. This might indicate an increased propensity of female patients to mount an adverse immune response. The pathological spectrum of ARMD has been described in detail in our previous work.16 One of the histological hallmarks of this response is ALVAL.22 In this condition, lymphocytes form thick cuffs around blood vessels. In its most advanced stage, lymphoid neogenesis is observed, and blood vessels can become hyalinised and obliterated.16 Tissue specimens from joint capsules affected by rheumatoid arthritis share some histological similarities with ALVAL tissue retrieved from patients with failed MoM joints.23 It is accepted that the incidence of a number of immune conditions such as rheumatoid disease is higher in women.24 It does not seem unreasonable, therefore, to suggest that women are predisposed to the development of ALVAL especially when one considers that, invariably, reports of local pathologies associated with MoM prostheses include a disproportionate number of female patients.6 11 19 We have previously, perhaps erroneously, attributed this observation entirely to the fact that smaller diameter resurfacings (used more in females) generally wear at a greater rate than equivalent larger joints.11 17

There also appears to be a difference in the failure rates of the ASR and BHR joints at equivalent blood Co concentrations. An explanation for this unexpected finding may be that wear debris released from the ASR bearing surface can more readily stimulate an immune cascade. It is well documented that wear volume and particle morphology can determine the resulting periprosthetic immune response.25–27 Indeed, it was for this very reason that MoM joints were introduced. It was thought that the overall reduction in volumetric wear rate and the smaller size of particles liberated from MoM prostheses would avoid the initiation of macrophage (histiocyte)-driven osteolysis caused by polyethylene debris.28 Leslie et al29 presented evidence that there is a significant difference in the morphology of ASR and BHR particles, with the median size of ASR particles being approximately half the size of BHR particles. If this is true, it would mean that ASR joints wearing at the same volumetric rate as a BHR joint expose the patient to a far greater number of particles.

When patients are exposed to very high levels of Co (>10 µg/l), the risk of development of osteolysis greatly increases in both ASR and BHR patients. The periprosthetic tissues of patients with Co concentrations in this category were riddled with macroscopically visible metal wear particles.16 Histological analysis, without exception, showed heavy infiltration of macrophages (histiocytes).16 This macrophage dominated response (similar to the response to polyethylene wear particles) is consistent with hip simulator data which have shown that particles released under harsh wear testing are much larger than those released under ideal wear conditions.30 Unfortunately, in this series of patients, only in those with advanced bony defects which required grafting were there any obvious changes on plain radiographs. This is quite likely due to the fact that opaque metal-laden debris is often deposited in the bony defects. We are now performing CT in patients with extremely elevated blood metal ion concentrations in order to better assess bony integrity and aid prerevision planning.

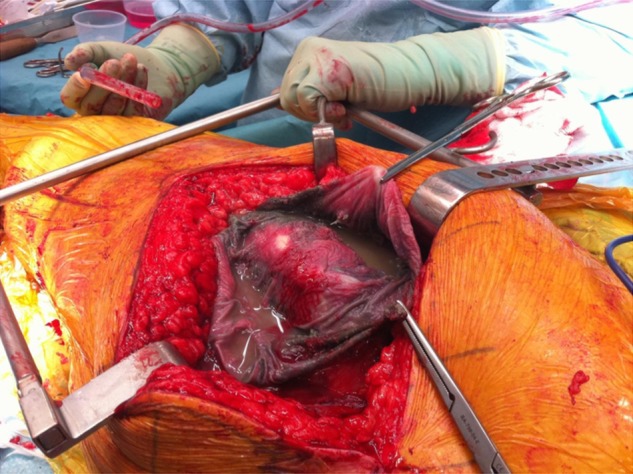

In summary, blood metal ion concentrations are a useful clinical tool, particularly in asymptomatic patients. They can be used as an indicator of the risk of the development of ARMD. Ion concentrations, if low, can be reassuring to both patients and surgeons and can also allow rationalisation of resources. Grossly elevated ion concentrations indicate the risk of early prosthetic failure and can be used to direct further investigations or implement closer follow-up. At our unit, which acts as a referral centre for the treatment of failed MoM joints, in total 40 patients with blood Co concentrations greater than 20 µg/l have undergone revision of their hip resurfacing so far. All were found to have macroscopic metal staining of the local tissues and 35 were found to have some degree of bone loss. In light of these findings, at our unit patients with grossly elevated metal ion concentrations are now offered revision surgery in the absence of symptoms. Figures 6 and 7 show two such examples. Figure 6 shows the intraoperative finding of a 50-year-old patient with an ASR with ‘slight’ pain only who had been reassured by his primary surgeon and sought a second opinion. Figure 7 shows the retrieved femoral neck of a patient with a BHR who also had minimal symptoms but elected for revision on account of elevated blood metal ion concentrations.

Figure 6.

Operative findings of a 55-year-old patient from another country. He had minimal discomfort but was not satisfied with his surgeon's opinion that ‘there was nothing to be concerned about’. His preoperative blood cobalt concentration was 217 µg/l. Note the gross metal staining of the tissues (metallosis) and abnormal fluid. There was extensive acetabular and femoral osteolysis.

Figure 7.

The femoral neck and prosthesis of a male patient in this study with a Birmingham Hip Resurfacing who was found to have blood cobalt of 155 µg/l on routine screening. He had no symptoms but elected for surgery 2 years later when he developed progressive discomfort in his hip. There were no obvious changes on plain x-rays. As can be seen on the right, there was a large cavity in the femoral neck filled with metal-stained, caseous material.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DL, RS, SN AVFN and SR conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. DL, RS, TJ, SN, PB, AVFN and RJ were responsible for the acquisition of the data, and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by DJ and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision and approval.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: DL and AVFN have received one-off funding for travel/accommodation reimbursement from Zimmer, Smith and Nephew, Depuy/Finsbury to attend educational orthopaedic conferences. He also works as an unpaid consultant to Wright Medical. TJ, SN and AVFN is an expert witness in litigation proceedings with regard to failed MoM joints. AVFN worked formerly as a consultant for DePuy.

Ethics approval: This study, as stated in the manuscript, was carried out as one of clinical need rather than research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.McMinn D, Treacy R, Lin K, et al. Metal on metal surface replacement of the hip. Experience of the McMinn prothesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treacy RB, McBryde CW, Shears E, et al. Birmingham hip resurfacing: a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulter G, Young DA, Dalziel RE, et al. Birmingham hip resurfacing at a mean of ten years: results from an independent centre. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012;94:315–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delaunay C, Petit I, Learmonth ID, et al. Metal-on-metal bearings total hip arthroplasty: the cobalt and chromium ions release concern. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96:894–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones DA, Lucas HK, O'Driscoll M, et al. Cobalt toxicity after McKee hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1975; 57-B:289–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, et al. Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement: a consequence of excess wear. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92-B:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glyn-Jones S, Roques A, Taylor A, et al. The in vivo linear and volumetric wear of hip resurfacing implants revised for pseudotumor. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011;93:2180–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langton DJ, Joyce TJ, Mangat N, et al. Reducing metal ion release following hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am 2011;42:169–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Smet K, De Haan R, Calistri A, et al. Metal ion measurement as a diagnostic tool to identify problems with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008;90:202–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langton DJ, Joyce TJ, Jameson SS, et al. Adverse reaction to metal debris following hip resurfacing: the influence of component type, orientation and volumetric wear. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93:164–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, et al. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90:847–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wynn-Jones H, Macnair R, Wimhurst J, et al. Silent soft tissue pathology is common with a modern metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2011;82:301–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medical Device Alert Ref: MDA/2012/008.

- 14.Hart AJ, Sabah S, Henckel J, et al. The painful metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91:738–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty: an end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1969;51-A:737–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natu S, Sidaginamale RP, Gandhi J, et al. Adverse reactions to metal debris: histopathological features of periprosthetic soft tissue reactions seen in association with failed metal on metal hip arthroplasties. J Clin Pathol 2012;65:409–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, et al. The effect of component size and orientation on the concentration of metal ions after resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008;90-B:1143–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Joint Registry of England and Wales 8th Annual Report. 2011

- 19.Glyn-Jones S, Pandit H, Kwon YM, et al. Risk factors for inflammatory pseudotumour formation following hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91:1566–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modelling survival data, statistics for biology and heath, Springer, 2000:350 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Mixed effects models in S and S-plus, statistics and computing, Springer, 2000:528 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willert HG, Bucchorn GH, Fayyazi A, et al. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints: a clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;87-A:28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takemura S, Braun A, Crowson C, et al. Lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatoid synovitis. J Immunol 2001;167:1072e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rojas-Villarraga A, Amaya-Amaya J, Rodriguez-Rodriguez A, et al. Introducing polyautoimmunity: secondary autoimmune diseases no longer exist. Autoimmune Dis 2012;2012:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams S, Tipper JL, Ingham E, et al. In vitro analysis of the wear, wear debris and biological activity of surface-engineered coating for use in metal-on-metal total hip replacements. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 2003;217:155–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howie AW, Haynes Dr, Rogers SD, et al. The response to particulate debris. Ortho Clin North Am 1993;24:517–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown C, Fisher J, Ingham E. Biological effects of clinically relevant wear particles from metal-on-metal hip prostheses. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 2006;220:355–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper RA, McAllister CM, Borden LS, et al. Polyethylene debris-induced osteolysis and loosening in uncemented total hip arthroplasty. A cause of late failure. J Arthroplasty 1992;3:285–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leslie IJ, Williams S, Figgitt M, et al. In vitro comparison of wear and wear debris of two contemporary designs of surface replacement.

- 30.Leslie IJ, Williams S, Isaac G, et al. High cup angle and microseparation increase the wear of hip surface replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2259–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vendittoli PA, Mottard S, Roy AG, et al. Chromium and cobalt ion release following the Durom high carbon content, forged metal-on-metal surface replacement of the hip . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007;89:441–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daniel J, Ziaee H, Pradhan C, et al. Six-year results of a prospective study of metal ion levels in young patients with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91:176–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.