Abstract

Objectives

Cardioankle vascular index (CAVI) is a new index of arterial stiffness independent of immediate blood pressure. Homocysteine (Hcy) is an independent risk factor for vascular diseases. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between Hcy and CAVI in the vascular-related diseases.

Design

Descriptive research.

Participants

88 patients (M/F 46/42) with or without hypertension, coronary artery disease or arteriosclerosis obliterans were enrolled to our study. They were divided into two groups according to the level of Hcy.

Methods

CAVI, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (CF-PWV) and carotid-radial pulse wave velocity (CR-PWV) were measured by VS-1000 and Complior apparatus.

Results

There was significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV, CR-PWV, CAVI in the entire group (r=0.33, p=0.002; r=0.51, p<0.001; r=0.42, p<0.001, respectively). And there was significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV, CR-PWV, CAVI in the vascular-related disease group (r=0.23, p=0.048; r=0.51, p<0.001; r=0.392, p=0.001, respectively). The level of Hcy was significantly higher in patients with one or more vascular diseases than in patients without vascular diseases. The levels of CF-PWV, CR-PWV and CAVI were significantly higher in Hcy ≥15 μmol/l group than in Hcy <5 μmol/l group (13.7±3.0 vs 10.8±2.5, p < 0.001; 10.6±2.1 vs 9.2±1.6, p=0.001; 9.30±2.1 vs 7.79±2.1, p=0.001, respectively). Multiple linear regression showed that Hcy, body mass index (BMI) and age were independent associating factors of CAVI in the entire study group (β=0.421, p=0.001; β=−0.309, p=0.006; β=0.297, p=0.012, respectively). And Hcy, BMI and age were independent influencing factors of CAVI in the vascular-related disease group (β=0.434, p=0.001; β=−0.331, p=0.009; β=0.288, p=0.022, respectively).

Conclusions

CAVI was positively correlated with Hcy in the vascular-related diseases.

Keywords: Vascular medicine

Article summary.

Article focus

To investigate the relationship between homocysteine (Hcy) and cardioankle vascular index (CAVI) in the vascular-related diseases.

Key message

Hcy was positively correlated with CAVI in the vascular-related diseases.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The present study first showed the relationship between Hcy and CAVI in the vascular-related diseases.

The small sample size, cases and controls were not perfectly matched.

Introduction

Arterial stiffness is a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. And it is one of the earliest detectable manifestations of adverse structural and functional changes within the vessel wall.1 Arterial stiffness can be measured by pulse wave velocity (PWV), which is considered as the gold standard method suggested by European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines.2 And our previous studies also showed that PWV was positively correlated with pulse pressure and it was increased in hypertension patients with left ventricular hypertrophy.3 4 However, PWV itself is essentially dependent on blood pressure especially immediate blood pressure. Cardioankle vascular index (CAVI), a new index of arterial stiffness independent of blood pressure, is recently developed by measuring of PWV and blood pressure.5 Recent studies have showed that CAVI was a reliable index of arterial stiffness in many vascular-related diseases.6 7

Homocysteine (Hcy) has been considered as an independent risk factor for atherosclseosis.8 The possible mechanism of this process includes endothelial cell damage, vascular endothelial dysfunction and enhanced oxidative stress. Recent studies showed that Hcy caused endothelial dysfunction through inhibiting the reactions between endothelial nitric oxide synthase and tetrahydrobiopterin.9 10 Our previous study showed that chronic hyperhomocysteinaemia (HHcy) contributed to coronary artery disease (CAD) by inhibiting dysfunction of the coronary artery endothelium.11 Increased arterial stiffness resulted from many factors such as endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cells proliferation, thickening of vascular wall. Kadota et al12 had showed positive correlation between Hcy and CAVI in general population. However, the relationship between CAVI and Hcy in the vascular-related diseases such as hypertension, CAD and arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO) was still unknown, especially in patients with one more kinds of vascular-related diseases. In the present study, we investigated the possible link between CAVI and Hcy in the vascular-related diseases such as hypertension, CAD and ASO.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Eight-eight patients (M/F: 46/42) with or without hypertension, CAD or ASO from vascular medicine department of Peking University Shougang Hospital from February 2012 to April 2012 were enrolled into our study. There were 57 patients with hypertension, 43 with CAD and 25 patients with ASO in the whole study group. And there were 12 patients without hypertension, CAD and ASO but suffering one of these two diseases, acute upper respiratory tract infection or acute gastritis.

Hypertension was defined as blood pressure measurement ≥140/90 mm Hg in three occasions at rest or participants with known cases of diagnosed hypertension before and taking antihypertensive drugs at present. CAD or ASO was defined as the narrowing or blockage of coronary artery or lower extremity artery diagnosed by angiography. HHcy was defined as the level of plasma Hcy ≥15 μmol/l.11

Enrolled patients were divided into four groups according to numbers of suffering vascular-related diseases. Also they were divided into two groups according to level of Hcy (Hcy <15 μmol/l group, N=43 and Hcy ≥15 μmol/l group, N=45). All participants gave their written informed consent. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Health Science Center, Peking University.

PWV measurement

Arterial stiffness was evaluated by measuring automatic PWV using the Complior apparatus. The basic principle of PWV assessment is that pressure pulse generated by ventricular ejection is propagated along the arterial system at a speed determined by elasticity of the arterial wall. Knowing the distance and pulse transit time, the velocity can be calculated. Patients were placed in recumbent position and, after a 10 min rest, underwent PWV measurement and carotid-femoral PWV (CF-PWV) and carotid-radial PWV (CR-PWV) was obtained automatically. CF-PWV and CR-PWV are both reliable index for arterial stiffness of vascular diseases.2 13 And we chose the right PWV for analysis.

Assessment of CAVI

CAVI was recorded using a VaseraVS-1000 vascular screening system (Fukuda Denshi, Tokyo, Japan) with the participant resting in a supine position. ECG electrodes were placed on both wrists, a microphone for detecting heart sounds was placed on the sternum, and cuffs were wrapped around both the arms and ankles. After automatic measurements, obtained data were analysed by software, and the value of CAVI was obtained automatically.14 And we chose the right CAVI for analysis.

Laboratory measurements

Blood samples were drawn from an antecubital vein in the morning after overnight fasting and collected into vacuum tubes containing EDTA for the measurement of plasma lipid and lipoprotein levels. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels were analysed by colorimetric enzymatic assays with the use of an autoanalyzer (HITACHI-7170, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were calculated. Fasting plasma glucose, Hcy and hs-C reactive protein were also determined by colorimetric methods of related metabolic products using the same autoanalyser at the central chemistry laboratory of the Peking University Shougang Hospital.

Statistical analysis

SPSS V.13.0 was used as statistical software in the present study. The differences between groups were analysed by Student t test and one-way analysis of variance. Proportions were analysed by χ2 test. Correlation coefficient was done to find linear relation between different variables using Spearman correlation coefficient. Multiple linear regressions were used to estimate the coefficients of the linear equation, involving independent variables that affected the value of the dependent variables. Values were shown as mean±SD unless stand otherwise and p<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study participants

The clinical characteristics of study participants are shown in table 1. Among these participants, 33 patients had only one of these three vascular-related diseases, 34 patients had two of these three vascular-related diseases, 9 patients had all of these three diseases and 12 participants with none of the vascular-related diseases. Our results showed that with the increasing numbers of suffered vascular-related diseases, the level of Hcy was increasing. Similar results were also found in the parameters of CF-PWV and CAVI. However, we found there was significant difference about age between these four groups.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in different groups according to the numbers of vascular-related diseases

| Characteristics | Group 0 N=12 |

Group 1 N=33 |

Group 2 N=34 |

Group 3 N=9 |

p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.4±9.5 | 63.5±13.1 | 73.2±10.0 | 76.1±10.3 | <0.01 |

| Sex (male/female) | 4/8 | 20/13 | 16/18 | 6/3 | 0.283 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.4±3.3 | 23.9±3.9 | 23.3±4.4 | 25.7±2.6 | 0.32 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 1.82±0.4 | 1.83±0.6 | 1.71±0.4 | 1.84±0.2 | 0.759 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.90±2.9 | 0.95±0.2 | 1.01±0.3 | 1.00±0.25 | 0.078 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/l) | 4.73±10.8 | 8.14±15.3 | 10.79±15.3 | 17.2±35.8 | 0.496 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.78±0.3 | 5.92±0.5 | 5.86±0.3 | 5.98±1.7 | 0.917 |

| Hcy (μmol/l) | 11.0±2.8 | 19.0±9.1 | 16.7±6.4 | 21.1±8.5 | 0.006 |

| Urinary microalbumin | 3.66±4.4 | 16.69±39.0 | 7.50±10.9 | 13.90±22.4 | 0.522 |

| Heart rate | 75.5±9.6 | 72.4±13.3 | 74.7±13.4 | 69.4±8.5 | 0.621 |

| ABI | 1.10±0.13 | 1.10±0.09 | 1.06±0.14 | 1.02±0.21 | 0.284 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 126.0±13.8 | 138.6±19.8 | 145.3±23.1 | 154.3±23.4 | 0.012 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 79.5±7.2 | 81.7±9.5 | 82.7±9.7 | 86.1±9.9 | 0.479 |

| CF-PWV | 9.17±2.6 | 12.33±3.0 | 13.03±2.8 | 13.85±1.86 | <0.001 |

| CR-PWV | 9.34±0.92 | 10.12±1.98 | 9.8±2.21 | 10.29±2.96 | 0.648 |

| CAVI | 7.51±0.9 | 8.23±2.4 | 9.09±2.3 | 9.34±2.0 | 0.08 |

The differences between groups were analysed by one-way analysis of variance; proportions were analysed by χ2 test.

Group 0, without diseases of hypertension, CAD, ASO; Group 1, with one of diseases of hypertension, CAD, ASO; Group 2, with two of diseases of hypertension, CAD, ASO; Group 3, with all diseases of hypertension, CAD, ASO.

ABI, ankle-brachial index; ASO, arteriosclerosis obliterans; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAVI, cardioankle vascular index; CF-PWV, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CR-PWV, carotid-radial pulse wave velocity; CRP, C reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; Hcy, homocysteine; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Next, we divided participants into two groups according to the level of Hcy. As shown in table 2, the level of CAVI was significant higher in patients with Hcy ≥15 μmol/l than in group with Hcy <15 μmol/l. The similar result was also found in another evaluation index of arterial stiffness-PWV. However, there was significant difference about age and sex between these two groups.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics in patients with Hcy <15 μmol/and Hcy ≥15 μmol

| Characteristics | Hcy <15 μmol/l (n=43) | Hcy ≥15 μmol/l (n=45) | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.9±13.0 | 71.9±11.5 | <0.01 |

| Sex (male/female) | 14/29 | 32/13 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9±4.2 | 23.3±3.8 | 0.48 |

| Hypertension (n (%)) | 26 (60.5) | 31 (68.9) | 0.41 |

| CAD (n (%)) | 18 (41.2) | 25 (55.6) | 0.2 |

| ASO (n (%)) | 8 (18.6) | 17 (37.8) | 0.03 |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 1.72±0.4 | 1.84±0.6 | 0.31 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.19±1.5 | 1.04±0.3 | 0.53 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/l) | 7.70±0.17 | 11.34±19.5 | 0.36 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.80±0.3 | 5.96±0.8 | 0.34 |

| Hcy (μmol/l) | 11.89±2.0 | 22.19±8.0 | <0.001 |

| Urinary microalbumin | 4.35±4.3 | 17.58±35.0 | 0.057 |

| Heart rate | 72.0±9.7 | 74.9±14.5 | 0.28 |

| ABI | 1.09±0.12 | 1.06±0.13 | 0.23 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 134.1±18.2 | 147.0±23.2 | 0.005 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 81.2±8.4 | 83.1±10.0 | 0.36 |

| CF-PWV | 10.8±2.5 | 13.7±3.0 | <0.001 |

| CR-PWV | 9.2±1.6 | 10.6±2.1 | 0.001 |

| CAVI | 7.79±2.1 | 9.30±2.1 | 0.001 |

Results were shown as mean±SD unless stand otherwise.

The difference between groups were analysed by Student's t test. Proportions were analysed by χ2 test.

ABI, ankle-brachial index; ASO, arteriosclerosis obliterans; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CAVI, cardioankle vascular index; CF-PWV, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CR-PWV, carotid-radial pulse wave velocity; CRP, C reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; Hcy, homocysteine; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Pearson correlations between PWV, CAVI and Hcy

PWV is a golden evaluation of arterial stiffness of vascular diseases. There are some kinds of PWV according to different arteries, such as CF-PWV and CR-PWV. CF-PWV and CR-PWV are both reliable index for arterial stiffness of vascular diseases.2 13 In the present study, patients with ASO had bilateral vascular lesions. And there was no significant difference between right side ankle-brachial index (ABI) and left side ABI in the entire study group (1.08±0.13 vs 1.07±0.15, p=0.612). In addition, there was no significant difference between right side ABI and left side ABI in participants with ASO (1.01±0.18 vs 1.05±0.14, p=0.376). And we chose the right PWV and CAVI for analysis.

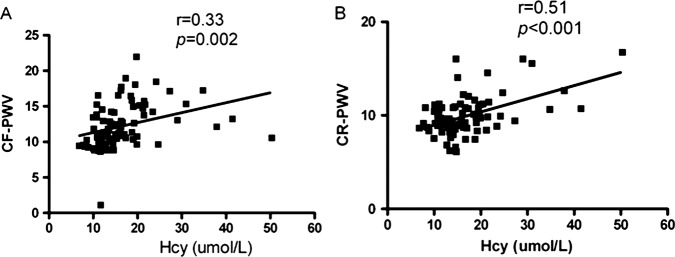

As shown in figure 1, CF-PWV was positively correlated with Hcy in entire group (r=0.33, p=0.002, figure 1A). There was also significant positive correlation between CR-PWV and Hcy in all patients (r=0.51, p<0.001, figure 1B). In addition, our results showed that there was significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV, CR-PWV in the vascular-related disease group (r=0.23, p=0.048; r=0.51, p<0.001, respectively).

Figure 1.

Relationship between CF-PWV and Hcy (A), CR-PWV and Hcy (B) in the entire study group. CF-PWV, carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity; CR-PWV, carotid-radial pulse wave velocity; Hcy, homocysteine.

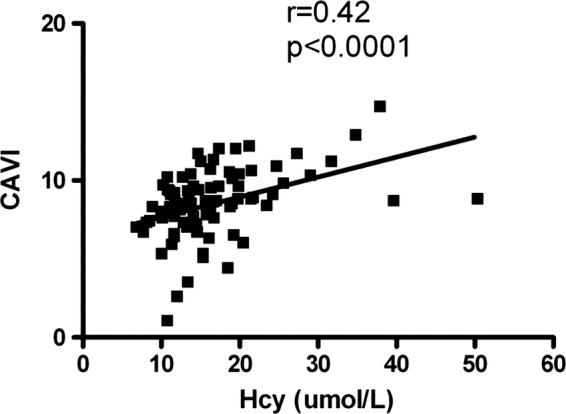

CAVI, a new index of arterial stiffness independent of blood pressure, was recently developed by measuring of PWV and blood pressure. And CAVI was not affected by immediate blood pressure. As shown in figure 2, there was significant positive correlation between CAVI and Hcy in all patients (r=0.42, p<0.0001). Also we found there was significant correlation between Hcy and CAVI in the vascular-related disease group (r=0.392, p=0.001). However, there was no significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV, CR-PWV, CAVI in patients without vascular-related diseases in the present study (r=0.14, p=0.661; r=152, p=0.620; r=0.056, p=0.855, respectively).

Figure 2.

Relationship between CAVI and Hcy in the entire study group. CAVI, cardioankle vascular index; Hcy, homocysteine.

As shown in tables 1 and 2, there was significant difference about age or sex between groups. So next, we investigated the possible relationship between CAVI, PWV and Hcy after adjusting the variable of age or sex. Our results showed that there was still significant correlation between CAVI and Hcy after adjustment for age in the entire study group(r=0.293, p=0.008). Also a positive correlation between PWV and Hcy was found after age adjusted in the entire study group (CF-PWV vs Hcy, r=0.282, p=0.010; CR-PWV vs Hcy, r=0.462, p<0.001; respectively). In addition, there was significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV, CR-PWV, CAVI after age and sex adjusted in the entire study group (r=0.26, p=0.022; r=0.38, p=0.001; r=0.27, p=0.014, respectively).

There were 12 patients without vascular-related diseases in the entire study group, so in next step, we analysed relationship between PWV, CAVI and Hcy in patients with vascular-related diseases. Our results showed that there was significant correlation between Hcy and CR-PWV, CAVI after adjustment for age in the vascular-related disease group (r=0.48, p<0.001; r=0.321, p=0.007, respectively), without significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV (r=0.21, p=0.079). After adjustment for age and sex, significant correlation between Hcy and CR-PWV, CAVI was found in the vascular-related disease group (r=0.40, p=0.001; r=0.298, p=0.013, respectively). However, there was no significant correlation between Hcy and CF-PWV after age and sex adjusted (r=0.193, p=0.115).

Multiple linear regression analysis

Multiple linear regressions were used to estimate the coefficients of the linear equation, involving independent variables that affected the value of CAVI. Our results showed that Hcy, body mass index (BMI) and age were independent influencing factors of CAVI in the entire study group (β=0.421, p=0.001; β=−0.309, p=0.006; β=0.297, p=0.012, respectively). And Hcy, BMI and age were independent influencing factors of CAVI in the vascular-related disease group (β=0.434, p=0.001; β=−0.331, p=0.009; β=0.288, p=0.022, respectively).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that there was positive correlation between Hcy and CAVI in the vascular-related diseases. CAVI and PWV were higher in patients with Hcy ≥15 μmol/l and Hcy was an independent influencing factor of CAVI in the vascular-related diseases.

An increase in arterial stiffness is not only a pathological status of hypertension, diabetes and CAD but also a strong predictor for the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality caused by these diseases. With the increasing of arterial stiffness, the incidence of hypertension, coronary heart disease increases. And arterial stiffness can be measured by PWV suggested by European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines. A lot of studies have showed the effect of PWV in the evaluation of arterial stiffness of vascular diseases. Aortic PWV was increasing in patients with diabetes mellitus or end-stage renal disease, indicating a higher arterial stiffness compared with healthy persons.15 A research of 710 hypertension patients revealed that aortic PWV is a useful marker and predictor of cardiovascular risk in these participants.16 Recently, in a prospective study of general Danish population, the investigator found that aortic PWV was a useful predictor for cardiovascular outcomes above and beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as 24 h mean blood pressure.17 Recent study showed that CR-PWV was a discriminator of intrinsic wall alterations during evaluation of endothelial function by flow-mediated dilatation and CR-PWV may predict the severity of the CAD.18 13 Our present study showed that CF-PWV and CR-PWV were higher in patients with vascular-related diseases than in participants without vascular-related diseases (12.80±2.9 vs 9.17±2.6, p<0.001; 10.00±2.2 vs 9.34±0.92, p=0.08, respectively). However, PWV itself is essentially dependent on blood pressure, especially immediate blood pressure. CAVI, a new index of arterial stiffness, is derived from stiffness parameter β, which is detected by carotid ultrasonic measurement.14

CAVI is a new evaluation index of arterial stiffness independent of immediate blood pressure. Recent studies have showed the role of CAVI in the prediction of vascular events in the vascular-related diseases such as metabolic syndrome (MS), diabetes, CAD, etc. In MS patients, there was significant positive correlation between CAVI and waist circumference, and CAVI increased significantly with the number of MS components.19 In another MS study, they found that CAVI was significantly decreased after 3-month period weight-reduction therapy through diet and exercise, so the determination of arterial stiffness by CAVI may be useful for evaluating and managing the cardiovascular diseases risks of MS patients.20 In a comparative study, researchers showed that the diagnostic accuracy of CAD was significantly higher in the CAVI than in the brachial ankle PWV, which suggested that CAVI had increased performance over brachial ankle PWV in predicting the CAD.21 22 Namekata showed that the CAVI method was a useful tool to screen persons with moderate to advanced levels of arteriosclerosis. CAD is one of the fatal and disabling diseases, some researchers fond that CAVI was significantly correlated with percentage plaque area in coronary arterial disease.23 A lot of studies have showed that CAVI was a reliable evaluation index of vascular-related diseases. Our present study showed that with the increasing numbers of vascular-related diseases suffering, the level of CAVI was increasing (table 1). CAVI was significantly higher in patients with vascular-related diseases than in control participants (8.73±2.3 vs 7.51±0.9, p=0.002). And we also found significant correlation between PWV and CAVI in the entire group (CAVI and CF-PWV: r=0.382, p<0.001; CAVI and CR-PWV: r=0.225, p=0.039, respectively).

Hcy is an independent risk factor of cardiovascular diseases. HHcy has been found in more than one half of patients with hypertension. The possible mechanism of this process includes endothelial cell damage, vascular endothelial dysfunction and enhanced oxidative stress.9 10 Our previous study showed that chronic HHcy contributed to CAD by inhibiting dysfunction of the coronary artery endothelium.11 So Hcy might damage the endothelium through complex mechanisms resulting endothelial dysfunction. Also Hcy could promote the proliferation of smooth muscle cells through inflammation and so on. Endothelial dysfunction and proliferation of smooth muscle cells of arterial medium could lead to the increasing of arterial stiffness. Previous study had showed positive correlation between Hcy and CAVI in general population.12 However, there was little research about the relationship between Hcy and CAVI in patients with one more kind of vascular-related diseases. In the present study, we found that CAVI was positively correlated with Hcy even after adjustment of other parameters, such as age and sex. The similar result was also found between PWV and Hcy. Hcy increases not only in hypertension patients but also in other vascular diseases. Hcy participates in the pathophysiological process of these diseases. HHcy was defined as the level of Hcy ≥15 μmol/l. Next, we compared the arterial stiffness between HHcy group and patients with Hcy <15 μmol/l. As shown in table 2, the levels of PWV and CAVI were significantly higher in group with Hcy ≥15 μmol/l than in group with Hcy <15 μmol/l. Finally, our research showed that Hcy was an independent influencing factor of CAVI in the vascular-related diseases. Folate administration has been consistently shown to reduce plasma Hcy even in healthy individuals without elevated Hcy levels.24 Lange et al25 found that folic acid treatment could reduce frequency of restenosis after angioplasty in patients with markedly elevated Hcy levels. Another study showed that low-dose folic acid treatment improves vascular function in CAD patients.26 Our study suggested that CAVI was higher in HHcy patients, so treatment should be made to lower Hcy in HHcy patients in order to reduce arterial stiffness. And thorough clinical research should be investigated in future.

However, there were some limitations in the study: the small sample size, cases and controls were not perfectly matched. Also some patients with hypertension and (or) CAD had oral medication such as amlodipine before coming to the hospital, this might affect our results to a certain extent. So a thorough research should be investigated in future. However, our study suggested that CAVI was a useful evaluation index for arterial stiffness, and there was positively correlation between CAVI and Hcy.

In conclusion, our study showed that CAVI and Hcy are closely associated among vascular-related diseases. More studies should be made to investigate the role of Hcy in the development of arterial stiffness.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HW and JL conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. JL, QW and HS were responsible for undertaking for the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. JL and HZ provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by HW and JL and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. JL was responsible for the acquisition of the data and XY and XF contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from The Capital Health Research and Development of Special to HY Wang (No. 2011-4026-02), and the hospital fund of Peking University Shougang Hospital to Hongyu Wang (No. 2010-Y002) and Jinbo Liu (No. 2012Y04).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: From the ethics committee of the Health Science Center, Peking University, China.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cavalcante JL, Lima JAC, Redheuil A, et al. Aortic stiffness. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1511–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007;25:1105–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni Y, Wang H, Hu D, et al. The relationship between pulse wave velocity and pulse pressure in Chinese patients with essential hypertension. Hypertens Res 2003;26:871–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Zhang W, Gong L, et al. Study of relationship between large artery distensibility and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with essential hypertension. Chin J Cardiol 2000;28:177–80 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirai K, Utino J, Otsuka K, et al. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter: cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI). J Atheroscler Thromb 2006;13:101–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KJ, Lee BW, Kim HM, et al. Associations between cardio-ankle vascular index and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. J Atheroscler Thromb 2011;18:328–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Namekata T, Suzuki K, Ishizuka N, et al. Establishing baseline criteria of cardio-ankle vascular index as a new indicator of arteriosclerosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011;11:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antoniades C, Antonopoulos AS, Tousoulis D, et al. Homocysteine and coronary atherosclerosis: from folate fortification to the recent clinical trials. Eur Heart J 2009;30:6–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topal G, Brunet A, Millanvoye E, et al. Homocysteine induces oxidative stress by uncoupling of NO synthase activity through reduction of tetrahydrobiopterin. Free Radic Biol Med 2004;36:1532–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meye C, Schumann J, Wagner A, et al. Effects of homocysteine on the levels of caveolin-1 and eNOS in caveolae of human coronary artery endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2007; 190:256–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He L, Zeng H, Li F, et al. Homocysteine impairs coronary artery endothelial function by inhibiting tetrahydrobiopterin in patients with hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010;299:E1061–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadota K, Takamura N, Aoyagi K, et al. Availability of cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) as a screening tool for atherosclerosis. Cir J 2008;72:304–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee YS, Kim KS, Nam CW, et al. Clinical implication of carotid-radial pulse wave velocity for patients with coronary artery disease. Korean Circ J 2006;36:565–72 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takaki A, Ogawa H, Wakeyama T, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index is a new non-invasive parameter of arterial stiffness. Circ J 2007;71:1710–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aoun S, Blacher J, Safar ME, et al. Diabetes mellitus and renal failure: effects on large artery stiffness. J Hum Hypertens 2001;15:693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blacher J, Asmar R, Djane S, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity as a marker of cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients. Hypertension 1999;33:1111–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen TW, Staessen JA, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation 2006;113:664–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torrado J, Bia D, Zócalo Y, et al. Carotid-radial pulse wave velocity as a discriminator of intrinsic wall alterations during evaluation of endothelial function by flow-mediated dilatation. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011;2011:6458–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Zhang X, Feng X, et al. Effects of metabolic syndrome on cardio-ankle vascular index in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2011;9:105–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satoh N, Shimatsu A, Kato Y, et al. Evaluation of the cardio-ankle vascular index, a new indicator of arterial stiffness independent of blood pressure, in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Hypertens Res 2008;31:1921–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horinaka S, Yabe A, Yagi H, et al. Comparison of atherosclerotic indicators between cardio ankle vascular index and brachial ankle pulse wave velocity. Angiology 2009;60:468–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takaki A, Ogawa H, Wakeyama T, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index is superior to brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity as an index of arterial stiffness. Hypertens Res 2008;31:1347–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horinaka S, Yabe A, Yagi H, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index could reflect plaque burden in the coronary artery. Angiology 2011;62:401–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward M, McNulty H, McPartlin J, et al. Plasma homocysteine, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, is lowered by physiological doses of folic acid. QJM 1997;90:519–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lange H, Suryapranata H, De Luca G, et al. Folate therapy and in-stent restenosis after coronary stenting. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2673–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirodaria C, Antoniades C, Lee J, et al. Global improvement of vascular function and redox state with low-dose folic acid: implications for folate therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 2007;115:2262–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.