Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify differences in patterns of developmental abnormalities between the brains of individuals with autism of unknown etiology and those of individuals with duplications of chromosome 15q11.2-q13 [dup(15)] and autism, and to identify alterations that may contribute to seizures and sudden death in the latter. Brains of 9 subjects with dup(15), 10 with idiopathic autism, and 7 controls were examined. In the dup(15) cohort, 7 subjects (78%) had autism, 7 (78%) had seizures, and 6 (67%) had experienced sudden unexplained death. Subjects with dup(15) autism were microcephalic, with mean brain weights 300 g less (1,177 g) than those of subjects with idiopathic autism (1,477 g; p < 0.001). Heterotopias in the alveus, CA4, and dentate gyrus and dysplasia in the dentate gyrus were detected in 89% of dup(15) autism cases but in only 10% idiopathic autism cases (p < 0.001). By contrast, cerebral cortex dysplasia was detected in 50% of subjects with idiopathic autism and in no dup(15) autism cases (p < 0.04). The different spectrum and higher prevalence of developmental neuropathological findings in the dup(15) cohort than in cases with idiopathic autism may contribute to the high risk of early onset of seizures and sudden death.

Keywords: Autism, Chromosome 15q11.2-q13 duplication, Developmental brain alterations, Seizures, Sudden unexpected death

INTRODUCTION

Autism is the most severe form of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is characterized by qualitative impairments in reciprocal social interactions, qualitative impairments in verbal and nonverbal communication, restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests and activities, and onset prior to the age of 3 years (1). Autism is heterogeneous, both phenotypically and etiologically. In 44.6% of affected children, autism is associated with cognitive impairment as defined by intelligence quotient scores of less than 70 (2). Epilepsy is a co-morbid complication diagnosed in up to 30% of individuals with autism (3). In 90% to 95% of cases the etiology of autism is not known (idiopathic or non-syndromic autism) (4, 5). Twin and family studies have indicated both a strong and a moderate heritability for ASD (6-8).

Approximately 5% to 10% of individuals with an ASD have an identifiable genetic etiology corresponding to a known single gene disorder, for example, fragile X syndrome or chromosomal rearrangements, including maternal duplication of 15q11-q13. Supernumerary isodicentric chromosome 15 [idic(15)] (formerly designated as inverted duplication 15) is a relatively common genetic anomaly that most often leads to tetrasomy or mixed trisomy/tetrasomy of the involved segments and arises from a U-type crossover between a series of low copy repeats (LCRs) located on the proximal long arm. Small heterochromatic idic(15) chromosomes, which do not include the 15q11-q13 region, are often familial and are not associated with a clinical abnormality (9, 10). The symptoms in people with idic(15) markers correlate with the extent of duplication of the Prader-Willi syndrome/Angelman syndrome critical region (PWS/ASCR) (15q11-q13) (10, 11). Larger supernumerary idic(15) chromosomes, which include the imprinted chromosome 15q11-q13 region, are associated with a cluster of clinical features that include intellectual deficits (IDs), seizures, autistic behavior, hypotonia, hyperactivity, and irritability (12). Duplications of chromosome 15q11-q13 account for approximately 0.5% to 3% of ASD and may be the most prevalent cytogenetic aberration associated with autism in most studies. These duplications range from 4 Mb to 12 Mb and may occur either through generation of supernumerary idic(15) chromosomes, or as interstitial duplications and triplications. For interstitial duplications, maternal origin confers a higher risk for an abnormal phenotype (13, 14) and the vast majority of reported chromosome 15 duplications [dup(15)] are maternally derived. A small number of subjects with duplications of paternal origin have been variously reported as being unaffected (13, 15-17), affected but without ASD (16, 18), or affected with ASD (19). Interstitial triplications [int trp(15)] are relatively rare but have invariably been associated with a severe phenotype, including ID, ASD, or autistic features, and frequently with seizures. The parent-of-origin effect is not evident in the reported cases of int trp(15), with both maternal and paternal triplications associated with poor outcome.

Clinical studies indicate that the majority of individuals diagnosed with dup(15) of maternal origin fulfill the criteria for the diagnosis of autism. In the first clinical reports, 24 individuals with idic(15) and autism were identified using standardized criteria of the DSM III-R (13, 15, 20-24). In several other studies of subjects with idic(15) chromosomes, autism was clinically diagnosed, although without the application of standardized measures of autism (25-27). Application of the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) (28) to another idic(15) cohort confirmed a high prevalence of autism; 20 of 29 children and young adults with idic(15) (69%) had an ASD (29).

The link between the extent of genetic duplication and clinical phenotype has not yet been determined, but genomic and functional profiling provides insights into the direct and indirect effects of the copy number gains associated with chromosome 15 duplications. The γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor subunit genes (α5, β3, and γ3) that have been implicated in the etiology of autism (30) are located in the susceptibility segment of duplicated chromosome 15 (31-34). A map of parent of origin-specific epigenetic modifications suggests that this imprinted locus may have links not only with autism but also with other psychiatric phenotypes (35). Differential methylations in the 15q11-q13 region, including the GABAA gene (30, 36-38), may contribute to epigenetic modifications and a broader clinical phenotypes in dup(15)/autism. Several other genes located in or near the 15q11-q13 region may contribute to a variable phenotype of autism, including a gene for juvenile epilepsy located near D15S165 (39) and a locus for agenesis of the corpus callosum (40).

We hypothesized that the neuropathology of autism with dup(15) differs from that of idiopathic autism and that it would provide an explanation for the high prevalence of seizures and associated sudden death in the dup(15) cohort. The aim of this comparative postmortem study of the brains of individuals diagnosed with idic(15) or int trp(15) [collectively referred to as dup(15)] and of individuals with idiopathic autism was to identify common neuropathological developmental defects for both cohorts and the patterns of changes distinguishing dup(15) from idiopathic autism. The dup(15) cohort examined exhibited a strikingly high prevalence of epilepsy, including intractable epilepsy, and a high rate of sudden unexpected death in childhood and early adulthood. Therefore, the second aim of the study was to identify patterns of neuropathological changes that may contribute to epilepsy and sudden death in the dup(15) cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The cohort of subjects diagnosed with dup(15) consisted of 9 subjects (9 to 39 years of age), including 5 males (55%) and 4 females (45%). The autistic cohort consisted of 10 subjects (2 to 52 years of age), including 9 males (90%) and 1 female (10%). The control cohort consisted of 7 subjects from 8 to 47 years of age, including 4 males (43%) and 3 females (57%). The brain of 1 subject diagnosed with dup(15) was excluded because of very severe autolytic changes, and the brain of 1 control subject was excluded because of lack of information about cause of death. The mean postmortem interval varied from 23.9 hours in the dup(15) cohort, to 19.6 hours in the idiopathic autism cohort, and 13.4 hours in the control group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Material Examined

| Group | Case # | Sex | Age, (y) | Cause of death | PMI (h) | Hem | Brain Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dup(15) autism | 1 | M | 9 | SUDEP | 13.6 | R | 1,130 |

| 2 | M | 10 | SUDEP | 17.7 | R | 1,070 | |

| 3 | M | 11 | SUDEP | 10.5 | R | 1,540 | |

| 4 | F | 15 | SUDEP (suspected) | 24.0 | LR | 1,141 | |

| 5 | F | 15 | Pneumonia | — | LR | 1,125 | |

| 6 | M | 20 | Cardiopulmonary arrest (choking on food) | 28.1 | L | 1,190 | |

| 7 | M | 24 | Pneumonia | 36.3 | L | 1,200 | |

| 8 | F | 26 | SUDEP (suspected) | 28.6 | R | 1,310 | |

| 9 | F | 39 | SUDEP | 32.8 | R | 890 | |

| Mean (SD) | 23.9 (9.2) | 1,177 (177) | |||||

| Idiopathic autism | 1 | M | 2 | Asphyxia (drowning) | 4.0 | R | 1,328 |

| 2 | F | 5 | Asphyxia (drowning) | 33.0 | R | 1,360 | |

| 3 | M | 5 | Asphyxia (drowning) | 25.5 | R | 1,560 | |

| 4 | M | 8 | Asthma attack | 13.8 | R | 1,740 | |

| 5 | M | 9 | SUDC | 3.7 | R | 1,690 | |

| 6 | M | 11 | Asphyxia (drowning) | — | R | 1,400 | |

| 7 | M | 28 | Seizure-related | 43.0 | R | 1,580 | |

| 8 | M | 32 | Brain tumor (glioblastoma multiforme) | — | L | 1,260 | |

| 9 | M | 51 | Heart failure | 22.2 | R | 1,530 | |

| 10 | M | 52 | Heart failure | 11.5 | L | 1,324 | |

| Mean (SD) | 19.6 (14.0) | 1,477 (166) | |||||

| Control | 1 | F | 8 | Rejection of cardiac transplant | 20.0 | R | 1,340 |

| 2 | M | 14 | Asphyxia (hanging) | 5.0 | R | 1,420 | |

| 3 | M | 14 | Multiple traumatic injuries | 16.0 | R | 1,340 | |

| 4 | M | 32 | Heart failure | 14.0 | R | 1,401 | |

| 5 | F | 33 | Bronchopneumonia | 6.0 | L | 1,260 | |

| 6 | F | 43 | Sepsis | 10.1 | L | 1,350 | |

| 7 | M | 47 | Myocardial infarct | 23.0 | L | 1,450 | |

| Mean (SD) | 13.4 (6.8) | 1,366 (63) |

PMI, postmortem interval; Hem, hemisphere; R, right; L, left; SUDEP, sudden unexpected death of subject with known epilepsy: SUDC, sudden unexpected death in childhood.

Clinical and Genetic Characteristics

Psychological, behavioral, neurological, and psychiatric evaluation reports and reports by medical examiners and pathologists were the source of the medical records of the examined postmortem subjects. Medical records were obtained following consent for release of information from the subjects’ parents. In the majority of subjects diagnosed as being affected by dup(15) and idiopathic autism, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) was administered to the donor family after the subject’s death as a standardized assessment tool to confirm an autism diagnosis (41). In addition, 6 of the subjects with dup(15) chromosomes were enrolled in a study of molecular contributors to the phenotype. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Nemours Biomedical Research. Prior to their deaths, 6 subjects (cases 1–4, 7, 8) had undergone behavioral and cognitive testing using the ADI-R, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale - Generic (ADOS-G) (42), and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (43,44) or the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales (45). Age of evaluation ranged from 45 to 251 months.

Molecular genetic evaluation using antemortem peripheral blood samples and lymphoblast cell lines for 8 of the dup(15) cases included genotyping with 19 to 33 short tandem repeat polymorphisms from chromosome 15, Southern blot analysis of dosage with 5 to 12 probes, and measurement of the methylation state at SNRPN exon α, as described (46). In addition, array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) was performed, using a custom bacterial artificial chromosome array (BAC) (47). Morphology of the duplication was confirmed by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) using 5 to 8 probes that detect sequences on chromosome 15q11q14 (46).

Tissue Preservation for Neuropathological Study

One brain hemisphere from each subject was fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, infiltrated with polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400 (Merck #807 485) and embedded in fresh PEG 1000 (48) and stored at 4°C. Tissue blocks were then cut at a temperature of 18°C into 50-μm-thick serial sections identified with a number and stored in 70% ethyl alcohol at room temperature. Free-floating hemispheric sections were stained with cresyl violet (CV) and mounted with Acrytol. To increase the probability of detection of small focal developmental defects, on average, 140 hemispheric CV-stained sections at a distance of 1.2 mm were examined per case.

Tissue acquisition for this project was based on individual tissue transfer agreements between the project’s principal investigator and several tissue banks, including i) the NICHD Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD; ii) the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA; and iii) the Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disabilities and Aging of the New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities (IBR). The Institutional Review Board of the IBR approved the methods applied in this study.

Statistical Analysis

Differences among groups in the presence or absence of heterotopias and dysplasias were examined using the Fisher exact test. Differences in the numbers of abnormalities were examined using the Mann-Whitney U (Wilcoxon signed ranks) test, or (for comparisons of all 3 groups) the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA (an extension of the U test), with exact probabilities computed using version 12 of the SPSS statistical package (SPSS, Inc. 2003, SPSS for Windows, Release 12.0). Brain weights were compared in one-way ANOVAs controlled for age.

RESULTS

Genetic Characteristics

For 8 subjects (cases 1–5, 7–9) in the dup(15) cohort, duplication chromosomes was characterized using a combination of genotyping, FISH, Southern blot, and array CGH with lymphoblasts generated from ante mortem blood samples (Table 2). All were maternally derived; 7 of these subjects were tetrasomic for the imprinted region between BP2 and BP3, although the BP involved were variable. The idic(15) present in cells from case 1 was generated by an exchange between copies of LCR3, causing tetrasomy that extended only to BP3. Four subjects (cases 2, 4, 5, 8) had the most common form of idic(15) chromosomes arising by NAHR between BP4 and BP5, leading to tetrasomy of the region between the p-arm and BP4, with trisomy for the interval between BP4 and BP5. Another subject (case 7) had a similar idic(15) chromosome but also carried a deletion between BP1 and BP2 on 1 homologue of chromosome 15 (Subject 00-03; 47). Case 3 had a complex tricentric supernumerary chromosome arising from NAHR between multiple copies of BP3, rendering him hexasomic for the region between the centromere and BP3 (46). One subject (case 9) had an int trp(15) chromosome that led to tetrasomy between BP1 and BP4 and trisomy for the interval between the fourth and fifth LCR, similar to the dosage seen in the BP4:BP5 idic(15) chromosomes.

Table 2.

Chromosome 15 Abnormalities in the dup(15) Cohort

| Case # | Chromosomal Alterations | Prader-Willi Syndrome/Angelman Syndrome Critical Region (PWS/ASCR) | Parental Origin of Abnormality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47, XY,+Idic(15)(q13;q13); Idic(15) arising from BP3:BP3 exchange.Subject 02-18, Wang et al (47) | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

| 2 | 47, XY,+idic(15)(q13;q13); Idic(15) arising from BP4:BP5 exchange.Subject 01-22, Wang et al (47) | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

| 3 | 47, XY,+der(15)(pter>q13∷q13>cen>q13∷q13>pter). Tricentric chromosome 15 arising from BP3:BP3 exchanges. Case 2, Mann et al (46); subject 00-29, Wang et al (47) | Hexasomy | Maternal |

| 4 | 47, XX,+idic(15)(q13;q13); Idic(15) arising from BP4:BP5 exchange.Subject 99-93, Wang et al (47) | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

| 5 | 47, XX,+der(15)(q13;q13); Idic(15) arising from BP4:BP5 exchange | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

| 6 | IDIC15 (2 extra copies of region from beginning of array to BP4) | Tetrasomy | Not determined |

| 7 | 47,XY,del(15)(q11.2)+idic(15)(q13;q13); Idic(15) arising from BP4:BP5 exchange; deletion of BP1:BP2 on one homologue of chromosome 15. Subject 00-03, Wang et al (47) | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

| 8 | 47,XX,+idic(15)(q13;q13); Idic(15) arising from BP4:BP5 exchange.Subject 99-27, Wang et al (47). | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

| 9 | 46,XX,trp(15)(q11.2q13).Subject 02-9, Wang et al (47) | Tetrasomy | Maternal |

The study of 5 subjects with idiopathic autism (cases 1–4, 9) revealed the absence of the relevant 15q11-q13 deletion or duplication between BP2 and BP3. In CAL105 normal karyotype was found. For 4 subjects (cases 5, 7, 8, 10), frozen tissue and genetic data were not available.

Clinical Characteristics

Seven of the 9 subjects with dup(15) (78%) were diagnosed with autism (Table 3). In 6 cases, autism was diagnosed clinically and was confirmed with postmortem ADI-R. In a 9-year-old male (case 1), autism was diagnosed with ADOS-G (Table 3). This case was reported as case 2 in Mann et al (46). An 11-year-old male (case 3) revealed impairments consistent with the diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS).

Table 3.

Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised–Based Diagnosis of Autism

| Group | Case # | Reciprocal Social Interactions (10) | Communication | Restricted, Repetitive, and Stereotyped Behavior (3) | Alterations Evident Before 36 mos (1) | Diagnosis (Test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal (8) | Non-verbal (7) | ||||||

| dup(15) autism | 1 | 7 | NA | 0 | 0 | 5 | Autism (ADOS-G) |

| 2 | 24 | NA | 11 | 5 | 3 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 3 | 18 | NA | 2 | 2 | 5 | PDD-NOS | |

| 4 | 26 | 22 | NA | 12 | 5 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | - | Autism (ADI-R) (score not available) | |

| 6 | 27 | 18 | NA | 4 | 5 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 7 | 23 | 22 | NA | 9 | 3 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 8 | 28 | 16 | NA | 9 | 5 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 9 | Unknown | ||||||

| Idiopathic autism | 1 | 14 | NA | 9 | 6 | 5 | Autism (ADI-R) |

| 2 | Autism (ADOS) | ||||||

| 3 | 22 | NA | 14 | 6 | 5 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 4 | 11 | NA | 8 | 2 | 4 | Atypical autism –ASD (ADI-R) | |

| 5 | 26 | NA | 12 | 5 | 4 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 6 | 25 | 20 | NA | 4 | 4 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 7 | 22 | 16 | NA | 5 | 3 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 8 | - | - | - | - | - | Autism (ADI-R) (score not available) | |

| 9 | 27 | 19 | 9 | 6 | 5 | Autism (ADI-R) | |

| 10 | - | - | - | - | - | Atypical autism – ASD (ADI-R score not available). | |

ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised; (cut-off scores); ADOS-G, Autism Diagnostic Observation Scale - Generic (42); NA, not applicable; PDD-NOS, Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified

In the idiopathic autism group, all 10 subjects were diagnosed clinically as having an autism spectrum disorder. Postmortem ADI-R confirmed a classification of autistic disorder in 6 cases. Two subjects, an 8-year-old male (case 4) and a 52-year-old male (case 10), were diagnosed with atypical autism or high-functioning autism. In a 5-year-old female (case 2), autism was diagnosed with ADOS-G. A 32-year-old male (case 8) and a 52-year-old male (case 10) were clinically diagnosed as autistic, but the ADI-R could not be conducted postmortem due to the unavailability of a caregiver who could report on behavior as a child.

Among the 9 examined subjects with dup(15) chromosomes, 7 individuals were diagnosed with seizures (78%) (Table 4). In 6 cases, death was sudden and unexplained in patients with epilepsy ([SUDEP], 6/9; 67%). In the autistic group of 10 subjects, epilepsy was diagnosed in 3 cases (30%); death was seizure-related in 1 case (1/10; 10%; Table 1). In a previously described cohort of 13 autistic subjects who were subject to postmortem examination (49), seizures were reported in 6 autistic subjects (46%); death was seizure-related in 4 cases (31%).

Table 4.

Behavioral, Neurological, and Other Clinical Observations

| Group | Case # | Psychiatric Disorders and Neurological Symptoms | Cognitive Assessment | Seizures (Age of Onset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dup(15) autism | 1 | Severe hypotonia. Regression in infancy. Abnormal response to pain and heat. | Profound ID (DQ < 20) | Infantile spasms. Intractable epilepsy (10 mos) |

| 2 | Hypotonia. Severe regression at age of 15 mos. Head banging. | Profound ID (DQ = 22) | Intractable epilepsy (8 mos) | |

| 3 | Regression with infantile spasms. Severe hypotonia. | Profound ID (DQ < 20) | Infantile spasms. Intractable epilepsy (10 mos). Vagus nerve stimulator. | |

| 4 | Delay of motor skills. Mild to moderate spastic quadriparesis. Abnormal response to pain, cold. | Severe ID (DQ = 31) | Seizures (11 y) | |

| 5 | Hyperactive, verbal | (—) | No record | |

| 6 | Sleep disorder. Abnormal response to pain, heat and cold. | (—) | No record | |

| 7 | Abnormal gait | Profound ID (DQ < 20) | Intractable epilepsy. (7 y). Vagus nerve stimulator. Callosotomy. | |

| 8 | Obsessive compulsive symptoms | Moderate ID (IQ = 36) | Epilepsy (16 y) | |

| 9 | Cerebral palsy. Microcephaly. Aggressive behavior. Trichotillomania. | Severe ID. (—) | Intractable epilepsy (9 y). Vagus nerve stimulator. | |

| Idiopathic autism | 1 | Self-stimulatory behavior | (—) | No record |

| 2 | Hyperactivity, attention deficit.Sleep disorder. Enhanced sensitivity to light and sound. | Cognitive delay (IQ = 65) | No record | |

| 3 | Sleep disorder | (—) | No record | |

| 4 | Self-stimulatory behavior | (—) | Epilepsy (8 y) | |

| 5 | Hypotonia | Moderate ID | No record | |

| 6 | No record | Moderate ID | Epilepsy | |

| 7 | Bipolar disorder | (—) | Epilepsy | |

| 8 | No record | (—) | No record | |

| 9 | Enhanced sensitivity to sound, heat and cold. Low pain threshold. | (—) | One grand mal seizure | |

| 10 | Bipolar disorder, social anxiety | (—) | No record |

DQ, Developmental Quotients; ID, intellectual deficit; — = No formal assessment of ID available

Brain Weight

The mean brain weight in dup(15) autism was 1,177 g, 300 g less than in idiopathic autism, and 189 g less than in the control group (Table 1). Age-adjusted means for these 3 groups were 1,171 g, 1474 g, and 1378 g, respectively (F [2 df] = 9.79, p <.001). Post-hoc tests showed the difference between the idiopathic and dup(15) autistic groups to be significant (Scheffé-corrected p = .001). The difference between the dup(15) and control groups was not significant, although suggestive (p = 0.06). The difference between the idiopathic and control groups was not significant.

Developmental Abnormalities in Autism Associated with dup(15) and Idiopathic Autism

Three major types of developmental changes, including i) heterotopias, ii) dysplastic changes, and iii) defects of proliferation resulting in subependymal nodular dysplasia, were detected in both the dup(15) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A323) and idiopathic autism (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324) cohorts. In the control group, 1 subject had small cerebellar subependymal heterotopias; 2 cases had dysplastic changes in the cerebellar flocculus and nodulus (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A325). Although all 9 dup(15) subjects and all 10 autistic subjects had developmental abnormalities, there were significant differences between the dup(15) autism and idiopathic autism cohorts in the number of developmental defects and their distribution (Table 5).

Table 5.

Topography and Type of Major Developmental Alterations

| Group | Case # | Hippocampus | Cerebral cortex Dysplasia | Cerebellum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heterotopia (Alveus, CA4, DG) | Dysplasia (DG) | WM Heterotopia | Flocculus Dysplasia | |||

| dup(15) autism | 1 | + | ++ | + | ||

| 2 | + | ++ | + | |||

| 3 | + | ++ | + | + | ||

| 4 | + | + | ||||

| 5 | + | +++ | ++ | |||

| 6 | + | ++ | + | |||

| 7 | + | +++++ | ++ | + | ||

| 8 | +++ | + | + | |||

| 9 | ++ | +++ | --- | |||

| 8 (89%) | 8 (89%) | 0 | 5 (56%) | 6/8 (75%) | ||

| Idiopathic autism | 1 | + | + | + | + | |

| 2 | + | + | ||||

| 3 | + | + | ||||

| 4 | + | + | + | + | ||

| 5 | + | |||||

| 6 | + | --- | ||||

| 7 | + | + | ||||

| 8 | + | |||||

| 9 | --- | |||||

| 10 | ||||||

| 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 5 (50%) | 6 (60%) | 4/8 (50%) | ||

| Control | 1 | |||||

| 2 | ||||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| 5 | ||||||

| 6 | ||||||

| 7 | + | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (14%) | ||

| p-values: dup(15) vs. idiopathic autism; | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.03 | ns | ns | |

| dup(15) vs. control; | 0.001 | 0.001 | ns | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

| autism vs. control. | ns | ns | 0.04 | 0.03 | ns | |

+ = The number of types of developmental alterations; percentages of subjects with developmental defects are in parentheses; ns, not significant; --- = Missing structure; DG = dentate gyrus; Statistical analyses: Fisher Exact Test, Mann-Whitney U Test.

Heterotopias

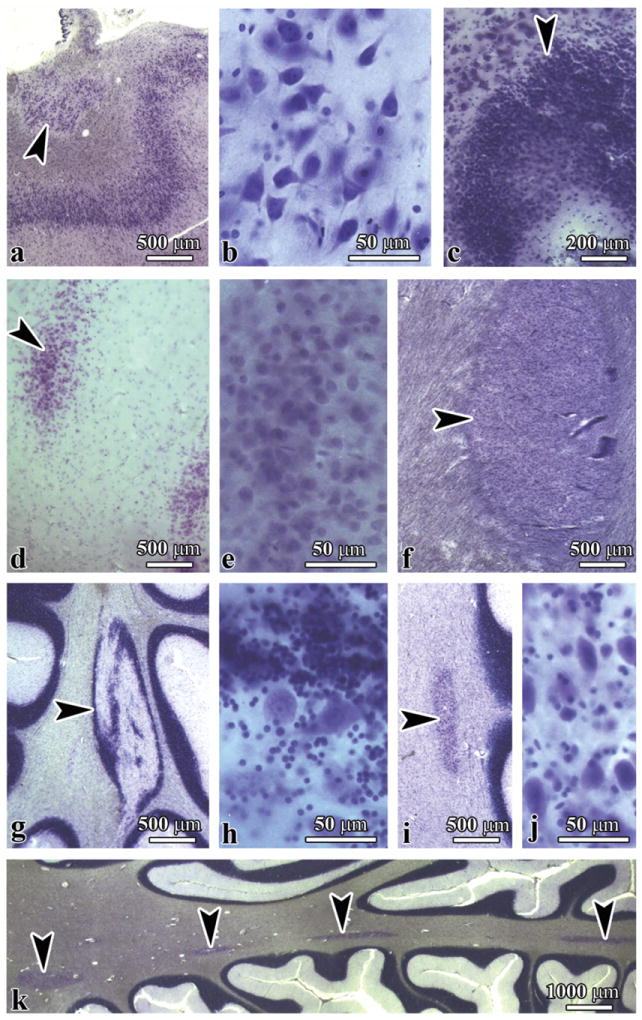

Migration developmental abnormalities were detected as heterotopias in the hippocampal alveus, the CA4 sector, the dentate gyrus (DG) molecular layer, and the cerebral and cerebellar white matter (Fig. 1). A description of each is given below.

Figure 1.

Topography and morphology of heterotopias in the brains of individuals with duplications of chromosome 15q11.2-q13 (subjects with dup[15] and autism). (A, B) Heterotopia (A, arrowhead) in the alveus composed of bipolar, multipolar, and pyramidal-like neurons shown at higher magnification in B. (C-E) Heterotopias composed of cells with the morphology of granule neurons in the CA4 sector (C, arrowhead) and in the molecular layer (arrowhead) of the dentate gyrus (D); higher magnification is shown in E. (F) Heterotopia (arrowhead) in the cerebral white matter. (G-J) Heterotopias in the cerebellum consist of mixed components of the cerebellar cortex (G, arrowhead), including granule and Purkinje cells (H); one is composed of one type of neuron (I, arrowhead), with the morphology of cells of cerebellar deep nuclei (J). (K) Multifocal heterotopias of both types in cerebellar white matter (arrowheads). (A, B, C, F) dup(15), Case 2; (D, E) dup(15), Case 6; (G-J) dup(15), Case 5; (K) idiopathic autism, Case 5.

Heterotopias in the Hippocampus

A relatively large proportion of heterotopic cells in the alveus had the morphology of pyramidal neurons, although they were much smaller than neurons in the cornu Ammonis and were spatially disoriented. Heterotopias composed of neurons with the morphology of granule neurons of the DG were detected in the CA4 sector and in the molecular layer of the DG. Heterotopias in the alveus, CA4, and DG were found in 8 dup(15) subjects (89%), 1 subject with idiopathic autism (10%), and no control subjects. This difference between dup(15) autism and idiopathic autism cohorts (p < 0.001) and dup(15) and control subjects was highly significant (p < 0.001), (Table 5). The difference between the idiopathic autism and control groups was not significant.

Heterotopias in Cerebellar White Matter

The morphology of the cerebellar heterotopias reflected 2 types of migration defects. The presence of a mixture of granule and Purkinje cells suggests that clusters of cerebellar cortical neurons do not reach their destination site (type 1). The second type of cerebellar heterotopia (type 2) is composed of one type of cells with the morphology of cerebellar deep nuclei neurons. Both types of heterotopias were composed of neuronal nuclear marker-positive cells mixed with glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive astrocytes (not shown). In some cases, multiple type 1 and 2 heterotopias were detected in the cerebellar white matter. In contrast to the significant difference in the prevalence of hippocampal heterotopias there was no significant difference in the prevalence of heterotopias in the cerebellar white matter between the dup(15) (56%) and idiopathic autism (60%) groups (Table 5). However, the differences between the dup(15) autism and control groups (p < 0.04) and between the idiopathic autism and control groups (p < 0.04) were significant. Heterotopias in cerebral white matter were rare in both the dup(15) (1/9; 11%) and idiopathic autism (1/10; 10%) group (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A323 and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324).

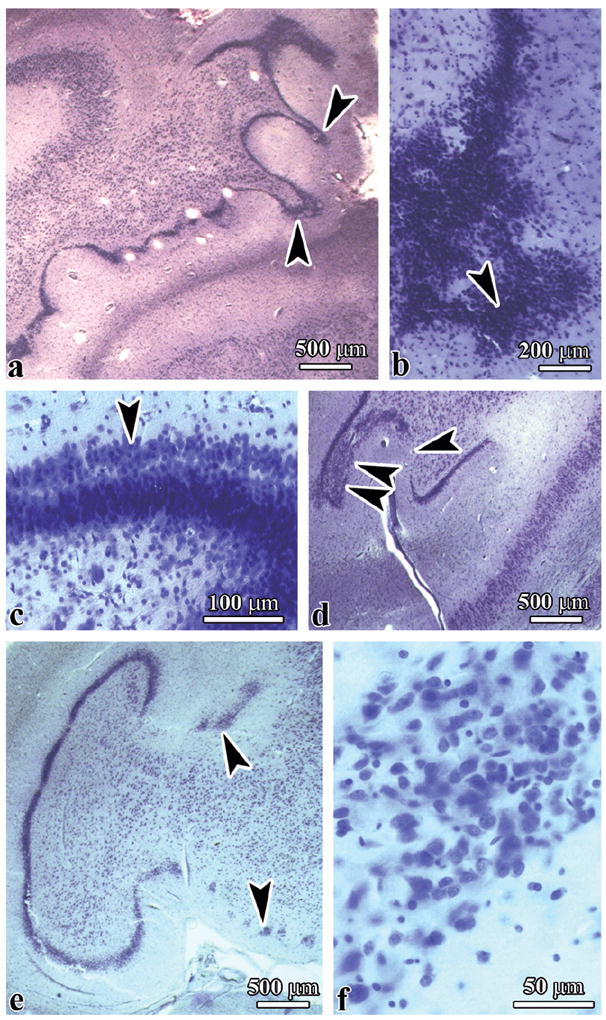

Dysplasias

Dysplastic changes reflect focal microdysgenesis in the hippocampal DG and cornu Ammonis, the amygdala, and in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex. Several types of dysplasia were detected in the DG, including hyperconvolution of the DG, duplication of the granular layer distorting the architecture of the molecular layer of the DG, irregular protrusions of the granular layer into the molecular layer, focal thinning and/or thickening of the granular layer, and fragmentation of the granular layer with the formation of isolated nests of granule cells (Fig. 2). The susceptibility of the DG to developmental abnormalities was several times more apparent in dup(15) syndrome than in idiopathic autism cases. They were detected in 8/9 (89%) subjects in the dup(15) group, and in only 1 autistic subject (1/10; 10%) (Table 5) (p < 0.001). The number of different types of developmental abnormalities in the dup(15) group ranged from 2 per case in 4 subjects, to 3 per case in 3 subjects, and 5 types in 1 case. The total number of different types of dysplasia was 22 times greater in the dup(15) than in idiopathic autism cohorts (p < 0.001). The difference between idiopathic autism (1 positive case) and the control group (no dysplastic changes in the DG) was not significant.

Figure 2.

Six types of dysplastic changes in the dentate gyrus of subjects diagnosed with duplications of chromosome 15q11.2-q13 (dup(15]) syndrome. (A-F) Hyperconvolution of the dentate gyrus within the hippocampal body (A), irregular large protrusions of the granular layer (B), duplication of the granular layer (C), focal thinning and discontinuity of granular layer (arrowhead), and thickening of the granular layer confirmed by examination of serial sections (D, 2 arrowheads), hippocampal malrotation and granular layer fragmentation into small clusters of cells of irregular shape and variable size (E, F). (A) dup(15), Case 8; (B) dup(15), Case 7; (C, E, F) dup(15), Case 3.

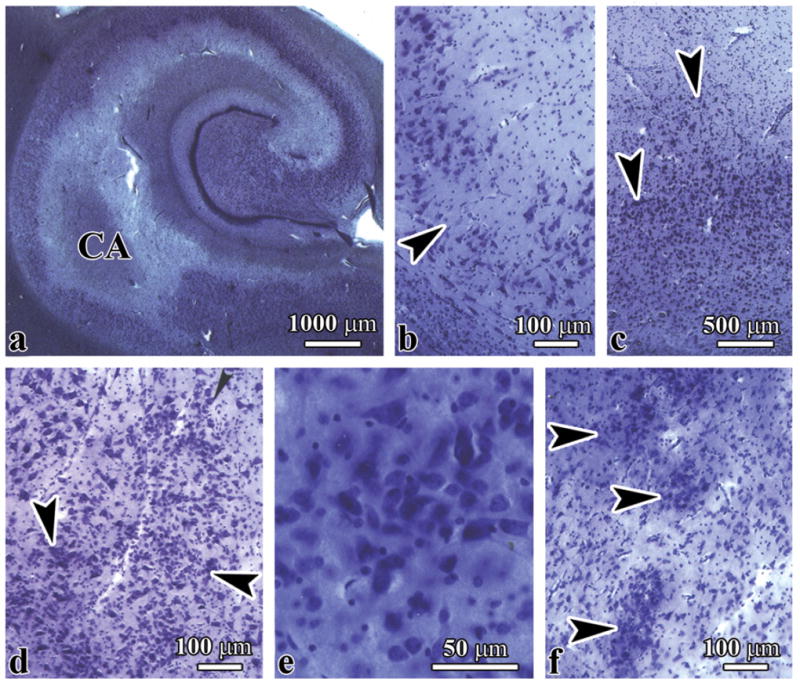

The spectrum of dysplastic changes in the cornu Ammonis comprised abnormal convolution of the CA1 sector, focal deficits of pyramidal neurons, and distortion of the shape, size, and spatial orientation of pyramidal neurons, clustering of dysplastic neurons in the CA1 sector, and many foci of severe microdysgenesis in the CA4 sector, with clustering of immature neurons (Fig. 3a-e). Dysplastic changes in the amygdala resulted in multiple irregular nests of 20 to 40 cells composed of relatively few small immature neurons and numerous oval or bipolar hyperchromatic neurons that were larger than normal amygdala neurons (Fig. 3f). Dysplastic changes in the cornu Ammonis were detected in 2 subjects with dup(15) syndrome and in 2 brains of autistic subjects (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A323 and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324).

Figure 3.

Multiple dysplastic changes in the cornu Ammonis (CA) and amygdala in an 11-year-old boy with hexasomy of chromosome 15q11.2q13 (Case 3). (A-C) There is abnormal convolution of the CA1 sector (A) with focal microdysgenesis of the pyramidal layer (B, arrowhead) and clustering of disoriented polymorphic neurons (C, arrowheads). (D, E) Marked multifocal microdysgenesis in the CA4 sector (D, arrowheads), with clustering of a mixture of small and large polymorphic neurons (E). (F) Multifocal microdysgenesis (arrowheads) in the amygdala is composed of small immature neurons and neurons that are larger than normal amygdala neurons.

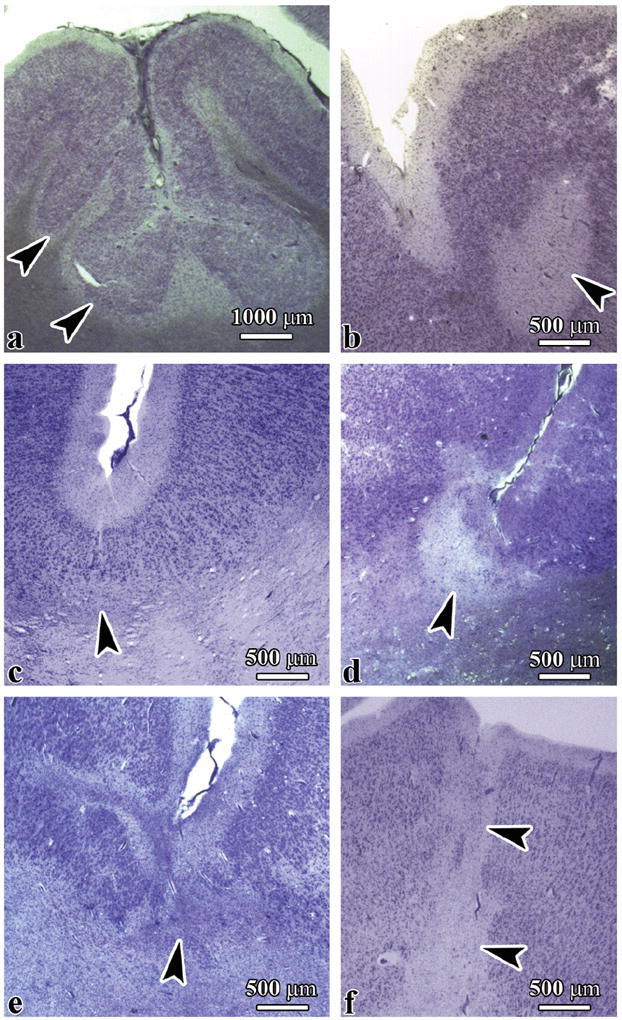

The presence of dysplastic changes in the cerebral cortex of 5 of the 10 subjects with idiopathic autism (50%) was in striking contrast to the absence of these changes in the dup(15) (p < 0.03) and control subjects (p < 0.04) (Table 5). Three types of cerebral cortex dysplasia were found in the idiopathic autism group: focal polymicrogyria, multifocal cortical dysplasia, and bottom-of-a-sulcus dysplasia (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324). Focal polymicrogyria, which reflects a gyrification defect, was found in the frontal lobe in an 8-year-old autistic male diagnosed with ASD (case 4), which resulted in local abnormal folding of the cortex with formation of numerous small and irregular microgyri and distortion of the cortical thickness and vertical/horizontal cytoarchitecture (Fig. 4a). The most common developmental abnormality was cortical dysplasia with focal hypo- or acellularity and loss of cortical vertical and horizontal cytoarchitecture (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

Cerebral cortex dysplasia autism spectrum disorder (ASD). (A, B) Polymicrogyria (A, arrowheads), focal hypocellularity or acellularity with lack of vertical and horizontal cortical organization (B, arrowhead) in an 8-year-old boy with ASD. (C-F) Bottom-of-a-sulcus dysplasia in a 5-year-old girl with idiopathic autism (Case 2). Focal dysplasia was limited to deep cortical layers (C), affected all layers except the molecular layer (D), and caused cortex fragmentation (E) or disruption of cortical ribbon continuity (F, arrowheads).

Another observed gyrification defect was multifocal bottom-of a-sulcus dysplasia with selective changes in the deepest layer, expansion of dysplastic changes to 2 to 3 deep layers of the cortex, or affecting the entire thickness of the cortex. This developmental abnormality was most often seen in the superior frontal and temporal gyrus, the Heschl gyrus, the middle temporal gyrus, the insula, and the parahippocampal gyrus in a 5-year-old female diagnosed with idiopathic autism (case 2) (Fig. 4c-f).

Three types of dysplastic changes were found in the cerebellum of the dup(15) subjects and the subjects with autism. These included dysplasia in parts of the nodulus and flocculus, vermis dysplasia, and focal polymicrogyria (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A323 and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324). In the nodulus and flocculus, dysplasia resulted in total spatial disorganization of the granular, molecular, and Purkinje cell layer; only a few small abnormally branched Purkinje cells were found to be dispersed among the granule cells in the affected areas. There were many inter-individual differences observed in the nodulus or flocculus volume affected by dysplastic changes. Cerebellar dysplasia was common observed in both cohorts. Nodulus dysplasia was present in 7 of 8 dup(15) subjects (87%) and in 6 of 8 autistic subjects (75%) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A323 and Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324). Flocculus dysplasia was detected in 6 of 8 dup(15) subjects (75%), 4 of 8 autistic subjects (50%), and 1 of 7 control subjects (Table 5). The difference between the autistic groups was not significant, but the difference between the dup(15) autism and control group was significant (p < 0.05).

Subependymal Nodular Dysplasia

Nodular dysplasia was found in the brain of a 15-year-old female diagnosed with dup(15) (case 5). This consisted of a single large nodule in the wall of the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle and numerous nodules in the wall of the lateral ventricle in the occipital lobe. Subependymal nodular dysplasia was also detected in the brain of a 39-year-old female diagnosed with dup(15) (case 9) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A323). There were numerous subependymal nodules less than 1 to 3 mm in diameter in the wall of the occipital horn of the lateral ventricle in a 32-year-old subject with idiopathic autism (case 8) (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/NEN/A324). These were composed of dysplastic neurons with a partially modified morphology of pyramidal, multi-, or bipolar neurons and oval medium and small cells. In all 3 cases, the nodules were free of oval or polygonal giant cells or ballooned glial cells. Examination of the thalamus, caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens, and globus pallidus did not reveal developmental qualitative abnormalities in these cohorts.

Differences Between the Global Pattern of Developmental Abnormalities in dup(15) and Autism

Although all dup(15) and autistic subjects had developmental abnormalities, the number of different types of developmental alterations detected in the brains of the dup(15) group was on average 2.3 times greater (6.9 per case; n = 9) than in the autistic subjects (3 per case; n = 10). Analysis of developmental alterations in 13 autistic subjects previously reported (49) revealed developmental abnormalities in the brains of all autistic subjects and a similar prevalence of alterations.

Other Neuropathological Changes

Selective and marked neuronal loss without gliosis was found in the pyramidal layer in the CA1 sector in the brain of a 10-year-old male with epilepsy [dup(15); case 2]. Pathological alterations extended from the head to the tail of the hippocampal formation, with loss of neurons in the range of 80% in the head and 50% in the body and tail. These findings might be the result of severe and frequent seizures.

An area of marked subpial gliosis was found within a sulcus between the inferior frontal and the orbital gyri in the brain of a dup(15) female with epilepsy and seizure-related asphyxia at the age of 26 years (case 8). Almost complete focal loss of the granular layer was associated with gliosis, thickening of the affected molecular layer, degeneration of astrocytes, and deposition of many corpora amylacea. These findings most likely represent Chaslin’s gliosis, indicative of epilepsy-related brain damage. This pathology coexisted with hyperconvolution of the DG, focal thinning, and duplication of the granular cell layer, considered developmental abnormalities contributing to abnormal electrical activity and seizures.

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of the clinical phenotype and genetic factors in autism is based on examination of thousands of individuals with idiopathic autism; however, between 1980 and 2003, only 58 brains of individuals with idiopathic autism were examined postmortem (50). Knowledge of the clinical and genetic characteristics of the dup(15) syndrome is based on examination between 1994 and 2006 of approximately160 cases (47, 51-54), but the neuropathology of dup(15) with and without autism has not been studied. Results of the application of an extended neuropathological protocol were previously reported for 13 brains of subjects with idiopathic autism (49). The current study characterizes qualitative neuropathological changes in the brains of 9 individuals with dup(15), including 7 diagnosed as having an ASD (78%). This autism prevalence is in the highest range reported in clinical studies. The association with autism in some of the earlier individual reports (i.e. 4 of 12 [33%] [55], or 6 of 17 [36%]) was not based on use of standardized screening (56). A standardized assessment of autistic manifestations in 29 children and adults with a supernumerary idic(15) detected 20 individuals (69%) with a high probability of ASD (29). All studies reported a significant variability in the autistic phenotype, severity of autistic features, delayed development and/or ID, and seizures among subjects with dup(15) (15).

Major Neuropathological Differences between dup(15) Autism and Idiopathic Autism

Numerous studies indicate that autism is associated with a short period of increased brain size (57-59) and an increased number of neurons (60). Macrocephaly was detected in 37% of autistic children younger than 4 years of age (61) and in 42% of the 19 twins diagnosed with idiopathic autism younger than 16 years of age (6). Postmortem studies (62, 63) and imaging studies (64) also provided converging evidence of increased brain volume in autism. Microcephaly has been observed in only 15.1% of 126 autistic children ages 2 to 16 years (65), and is usually associated with severe pathology (66, 67), ID, and other medical disorders (65).

This study revealed a high prevalence of microcephaly in the dup(15) autism cohort examined postmortem, i.e. the mean weight of the brains of subjects with dup(15) autism was 300 g less than that of subjects with idiopathic autism, and 189 g less than in the controls (p < 0.001 for both). The characteristics of head circumference and brain volume in dup(15) cohorts have been studied less comprehensively than in idiopathic autism, but published reports also show a strong prevalence of microcephaly. A summary of records from 107 supernumerary inv dup(15) cases revealed that only 3 subjects had macrocephaly (2.8%), but 6 times more cases (18; 16.8%) had microcephaly (15). Battaglia detected microcephaly in radiological evaluations of 1 in 4 cases with dup(15) who ranged in age from 4 to 8 years (68). These data suggest the failure of mechanisms controlling brain growth in autism, resulting in the prevalence of macrocephaly in idiopathic autism and of microcephaly in dup(15) autism.

Our extended neuropathological protocol revealed several striking differences between the pattern of developmental alterations in dup(15) autism and idiopathic autism. Neuronal migration defects in the hippocampus resulting in heterotopias in the alveus, CA4, and DG were 8 times more common in dup(15) autism (89% of subjects) than in idiopathic autism (10%) (p < 0.001). The second developmental abnormality distinguishing dup(15) autism from idiopathic autism was the dysplasia that occurred 8 times more often in the dentate gyrus of subjects with dup(15) and the different types of developmental abnormalities that occurred 22 times more often in the dentate gyrus of subjects with dup(15) (p < 0.001). The third factor differentiating these 2 cohorts was the absence of cerebral cortex dysplasia in dup(15) autism and the presence of this pathology in 50% of subjects with idiopathic autism (p < 0.03). The increased number of developmental alterations and the topographic differences suggest significant differences between mechanisms contributing to abnormal neuronal migration and altered cytoarchitecture in these 2 cohorts.

Linkage and gene-mapping analysis, molecular reports, and clinical studies revealed the link between de novo, maternally derived proximal 15q chromosome alterations, and autism (13, 15, 27, 33, 56, 69-72). This postmortem study suggests that neuropathological profile with microcephaly and multiple focal developmental defects is another marker of maternally derived proximal 15q chromosome alterations contributing to autistic phenotype.

Although ASD and epilepsy are heterogeneous disorders, they often occur together. This may indicate that these disorders share some underlying mechanisms, and that epileptogenesis affects brain structure and function, which modify the clinical manifestations of autism. Approximately 30% of children with autism are diagnosed with epilepsy and 30% of children with epilepsy are diagnosed with autism (73). Significant cognitive impairment is present in approximately 50% of all individuals who have autism (74). Early onset of seizures contributes to clinical regression, enhanced severity of autistic phenotype, and enhanced mortality. The rate of death among autistic subjects is 5.6 times higher than expected (75), and epilepsy- and cognitive impairment–related accidents account for most of the deaths (75-78). The diagnosis of epilepsy in 78% (7/9) of postmortem-examined individuals with dup(15) indicates that epilepsy is an important component of the clinical phenotype in the majority of individuals diagnosed with dup(15).

Microcephaly might be one of several indications of brain immaturity that increases the risk of epilepsy. The immature brain exhibits increased excitation, diminished inhibition, and increased propensity for seizures in infancy and early childhood (79). The reduced volume of neurons in the majority of subcortical structures and some cortical regions in the brains of 4- to 8-year-old autistic children appears to reflect brain immaturity in early childhood (80). In the normally developing brain, maturation of the frontal and temporal cortex is associated with differential expression of 174 genes; however, none of these genes is differentially expressed in ASD (81). Altered development of neurons resulting in brain immaturity may contribute to an increased tendency for the seizures and epileptogenesis observed in the examined cohort. Very early onset of intractable epilepsy (at 10, 8, and 10 months, respectively) was reported in all 3 of the youngest individuals diagnosed with dup(15), who died as a result of SUDEP at 9, 10, and 11 years of age. These findings suggest that very early onset of seizures and very severe seizures may increase the risk of SUDEP in this cohort. Severe ID in all 3 of these individuals indicates that brain immaturity and a profound ID are another SUDEP risk factor in the examined cohort of subjects with dup(15). The combination of all these factors may contribute to death at a very early age (~10 years).

Sudden unexpected death in childhood (SUDC) is the sudden death of a child older than 1 year of age that, in spite of a review of the clinical history, circumstances of death, and complete autopsy with appropriate ancillary testing, remains unexplained. SUDC occurs throughout childhood (<18 years), but occurs most commonly between the ages of 1 and 4 years (82, 83). SUDEP is an unexpected and unexplained death that occurs in patients with known epilepsy, including children, and is typically associated with sleep (84, 85). Kinney et al reported several types of hippocampal anomalies in SUDC cases, including hyperconvolution of the DG, focal duplication of the DG, granular nodular heterotopia, abnormal folding of the subiculum, and focal clustering of pyramidal neurons in the cornu Ammonis (86). These developmental anomalies are considered a cause of seizure-related autonomic and/or respiratory dysfunction and sudden death (87-89). Kinney et al proposed that these anomalies represent an epileptogenetic focus that, when triggered by fever, trivial infection or minor head trauma at a susceptible age, may result in unwitnessed seizure, cardiopulmonary arrest, and sudden death (86). The presence of these developmental anomalies in the examined brains of individuals with dup(15) may explain SUDEP in 5 cases and SUDC in 2 other cases. The presence of these changes in the hippocampus of subjects with dup(15) who died from causes other than SUDEP or SUDC suggests that they also were at higher risk for sudden unexpected death. Collectively, these data indicate that the risk of SUDC is much higher in the dup(15) cohort than in the general population with SUDC in which there is an overall rate of 57 of 100,000 deaths per year (90).

Microdysgenesis is not specific for dup(15), epilepsy, or autism; it has been reported in ID (91), psychosis (92), and dyslexia (93), as well as in some control subjects. None of these developmental alterations can be considered pathognomonic of an “epileptic” brain (83), but changes in the cohort affected by dup(15) or idiopathic autism reveal significant differences. This indicates that not a single lesion but, instead, a complex pattern of developmental defects distinguishes these subjects. A 2.3-fold higher prevalence of these developmental abnormalities, 2.3 times higher prevalence of epilepsy, and 6 times higher prevalence of epilepsy-related death in the dup(15) cohort compared to the idiopathic autism group suggest that the mechanisms leading to developmental structural alteration in the hippocampal formation are a major contributor to epilepsy and SUDEP/SUDC in dup(15). These appear to be a much weaker contributor to epilepsy and SUDEP in idiopathic autism. The results presented in this report reinforce the hypothesis that additional copies of the critical 15q11-q13 region are causally related to the autism phenotype and developmental abnormalities contributing to epilepsy and to an increased risk of SUDEP and SUDC. Future studies of the expression and distribution of proteins encoded by GABAA receptor subunit genes (α5, β3, and γ3) and the gene for juvenile epilepsy located near D14S165 on chromosome 15 may explain the role of duplication or triplication of these genes in autism and the enhanced susceptibility to seizures in dup(15) syndrome.

In conclusion, despite the common clinical diagnosis of autism in the dup(15) and idiopathic cohorts, significant differences in brain growth and focal developmental defects of neuronal migration and cytoarchitecture indicate that the dup(15) autistic phenotype is a product of unique genetic, molecular, and neuropathological alterations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by funds from the New York State Office for People With Developmental Disabilities, a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense Autism Spectrum Disorders Research Program (AS073234, Program Project; J.W., T.W., A.C.), a grant from Autism Speaks (Princeton, New Jersey; J.W.), and an Autism Center of Excellence (NIH P50 HD055751; EHC). Clinical and molecular investigations of the subjects with chromosome 15 duplications were supported by the Collaborative Programs for Excellence in Autism Research (NIH U19 HD35470; N.C.S.) and Nemours Biomedical Research, duPont Hospital for Children.

The authors thank Maureen Marlow for editorial corrections and Jadwiga Wegiel, Cathy Wang, and En Wu Zhang for histology. Tissue and clinical records acquisition was coordinated by the Autism Tissue Program (Princeton, NJ; Directors: Jane Pickett, PhD and Daniel Lightfoot, PhD). Carolyn Komich Hare, MSc provided results of postmortem application of ADI-R. The tissue was obtained from the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, Belmont, MA, supported in part by PHS grant number R24-MH 068855; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD; and the Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disabilities and Aging of the New York State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, Staten Island, NY. We are deeply indebted to the Dup15q Alliance, and the families of the tissue donors who have made this study possible.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: JW, research design and manuscript writing; NCS, EHC, MC, WTB, genetic studies and manuscript writing; IK, TW, WTB, BL, neuropathological evaluation; ILC and EL, clinical data evaluation; KN, JW, HI, SYM, EM, AC, VC, neuropathological documentation; database management; data extraction, verification, interpretation, and formatting for statistical analysis; and manuscript writing; MF, statistical analysis.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2007 doi: 10.3109/15360288.2015.1037530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuchman RF, Rapin I. Epilepsy in autism. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:352–8. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillberg C, Coleman M. Autism and medical disorders: A review of the literature. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1996;38:191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1996.tb15081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boddaert N, Zilbovicius M, Philipe A, et al. MRI findings in 77 children with non-syndromic autistic disorder. PLOS one. 2009;4:e4415. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004415. www.plosone.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I, et al. Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: Evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med. 1995;25:63–77. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700028099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B. Genetics of autism: Complex etiology for a heterogenous disorder. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:943–55. doi: 10.1038/35103559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1095–102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckton KE, Spowart G, Newton MS, et al. Forty four probands with an additional “marker” chromosome. Hum Genet. 1985;69:353–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00291656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S, Spinner NB, Zackai EH, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular characterization of inverted duplicated chromosomes 15 from 11 patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:753–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson WP, Wagstaff J, Bernasconi F, et al. Uniparental disomy explains the occurrence of the Angelman or Prader-Willi syndrome in patients with an additional small inv dup(15) chromosome. J Med Genet. 1993b;30:756–60. doi: 10.1136/jmg.30.9.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wisniewski L, Hassold T, Heffelfinger J, Higgins JV. Cytogenetic and clinical studies in five cases of inv dup(15) Hum Genet. 1979;50:259–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00399391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook EH, Jr, Lindgren V, Leventhal BL, et al. Autism or atypical autism in maternally but not paternally derived proximal 15q duplication. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:928–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson AJ, Mogk R, Rothenmund H, et al. Paternal origin of a small, class I inv dup(15) Am J Med Genet. 2002;107:334–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroer RJ, Phelan MC, Michaelis RC, et al. Autism and maternally derived aberrations of chromosome 15q. Am J Med Genet. 1998;76:327–36. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980401)76:4<327::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohandas TK, Park JP, Spellman RA, et al. Paternally derived de novo interstitial duplication of proximal 15q in a patient with developmental delay. Am J Med Genet. 1999;82:294–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton PF, Dennis NR, Browne CE, et al. The phenotypic manifestations of interstitial duplications of proximal 15q with special reference to the autistic spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:675–85. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao R, Jalal SM, Snow K, et al. Characteristics of two cases with dup(15)(q11.2-q12): One of maternal and one of paternal origin. Genet Med. 2000;2:131–5. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolton PF, Veltman MWM, Weisblatt E, et al. Chromosome 15q11-13 abnormalities and other medical conditions in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Genet. 2004;14:131–7. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-III-R. Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillberg C, Steffenburg S, Wahlstrom J, et al. Autism associated with marker chromosome. J Am Acad Child Adol Psych. 1991;30:489–94. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghaziuddin M, Sheldon S, Venkataraman S, et al. Autism associated with tetrasomy 15: A further report. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 1993;2:226–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02098582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker P, Piven J, Schwartz S, et al. Brief report: Duplication of chromosome 15q11-13 in two individuals with autistic disorder. J Autism Develop Dis. 1994;24:529–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02172133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bundey S, Hardy C, Vickers S, et al. Duplication of the 15q11-13 region in a patient with autism, epilepsy and ataxia. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36:736–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb11916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schinzel A. Particular behavioral symptomatology in patients with rare autosomal chromosome aberrations. In: Schmidt W, Nielsen J, editors. Human Behavior and Genetics. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland; 1981. pp. 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grammatico P, Di Rosa C, Rocella M, et al. Inv dup(15): Contribution to the clinical definition of the phenotype. Clin Genet. 1994;46:233–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flejter WL, Bennett-Baker PE, Ghaziuddin M, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular analysis of inv dup(15) chromosomes observed in two patients with autistic disorder and mental retardation. Am J Med Genet. 1996;61:182–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960111)61:2<182::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilliam J. The Gilliam Autism Rating Scale. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1995. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rineer S, Finucane B, Simon EW. Autistic symptoms among children and young adults with isodicentric chromosome 15. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:428–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980907)81:5<428::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hogart A, Nagarajan RP, Patzel KA, et al. 15q11-13 GABAA receptor genes are normally biallelically expressed in brain yet are subject to epigenetic dysregulation in autism spectrum disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:691–703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buxbaum JD, Silverman JM, Smith CJ, Greenberg DA, Kilifarski M, Reichert J, Cook EH, Jr, Fang Y, Song CY, Vitale R. Association between a GABRB3 polymorphism and autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:311–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bass MP, Menold MM, Wolpert CM, et al. Genetic studies in autistic disorder and chromosome 15. Neurogenetics. 1999;2:219–26. doi: 10.1007/s100489900081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook EH, Courchesne RY, Cox NJ, et al. Linkage-disequilibrium mapping of autistic disorder, with 15q11-13 markers. Am J Hum Gen. 1998;62:1077–83. doi: 10.1086/301832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menold MM, Shao Y, Wolpert CM, et al. Association analysis of chromosome 15 GABAA receptor subunit genes in autistic disorder. J Neurogenet. 2001;15:245–59. doi: 10.3109/01677060109167380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharp AJ, Migliavacca E, Dupre Y, et al. Methylation profiling in individuals with uniparental disomy identifies novel differentially methylated regions on chromosome 15. Genome Res. 2010;20:1271–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.108597.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meguro M, Mitsuya K, Sui H, et al. Evidence for uniparental, paternal expression of the human GABAA receptor subunit genes, using microcell-mediated chromosome transfer. Hum Mol Genet. 1997:2127–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Talebizadeh Z, et al. Microarray analysis of gene/transcript expression in Angelman syndrome: Deletion versus UPD. Genomics. 2005;85:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabriel JM, Higgins MJ, Gebuhr TC, et al. A model system to study genomic imprinting of human genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14857–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williamson M, Elmslie FV, Bate L, et al. Identification and characterization of a CHRNA7-related gene adjacent to CHRNA7 on chromosome 15q14. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:A196. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casaubon LK, Melanson M, Lopes-Cendes I, et al. The gene responsible for a severe form of peripheral neuropathy and agenesis of the corpus callosum maps to chromosome 15q. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:28–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, et al. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32 Special Issue: Effectiveness of early education in autism. New York, NY: Klüver Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2006. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mullen EM. In: Mullen Scales of Early Learning. AGS, editor. Circle Pines MN: American Guidance Service Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akshoomoff N. Use of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning for the assessment of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Neuropsychol. 2006;12:269–77. doi: 10.1080/09297040500473714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roid GH. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales. Fifth Edition. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2003. Technical Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mann SM, Wang NJ, Liu DH, et al. Supernumerary tricentric derivative chromosome 15 in two boys with intractable epilepsy: Another mechanism for partial hexasomy. Hum Genet. 2004;115:104–11. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang NJ, Liu D, Parokonny AS, et al. High-resolution molecular characterization of 15q11-q13 rearrangements by array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) with detection of gene dosage. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:267–81. doi: 10.1086/422854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iqbal K, Braak H, Braak E, et al. Silver labeling of Alzheimer neurofibrillary changes and brain β-amyloid. J Histotech. 1993;16:335–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wegiel J, Kuchna I, Nowicki K, et al. The neuropathology of autism: Defects of neurogenesis and neuronal migration, and dysplastic changes. Acta Neuropath. 2010;119:755–70. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmen SJMC, van Engeland H, Hof PR, et al. Neuropathological findings in autism. Brain. 2004;127:2572–83. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webb T. Inv dup (15) supernumerary marker chromosomes. J Med Genet. 1994;31:585–94. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.8.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webb T, Hardy CA, King M, et al. A clinical, cytogenetic and molecular study of ten probands with supernumerary inv dup(15) marker chromosomes. Clin Genet. 1998;53:34–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.1998.531530107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schinzel A, Niedrist D. Chromosome imbalances associated with epilepsy. Am J Med Genet. 2001;106:119–24. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dennis NR, Veltman MVM, Thompson R, et al. Clinical findings in 33 subjects with large supernumerary marker(15) chromosomes and 3 subjects with triplication of 15q11-q13. Am J Med Genet. 2006;140A:434–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leana-Cox J, Jenkins L, Palmer CG, et al. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of inv dup(15) chromosomes, using probes specific for the Prader-Willi/Angelman syndrome region: Clinical implications. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;54:748–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crolla JA, Harvey JF, Sitch FL, et al. Supernumerary marker 15 chromosomes: A clinical, molecular and FISH approach to diagnosis and prognosis. Hum Gen. 1995;95:161–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00209395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lainhart JE, Piven J, Wzorek M, et al. Macrocephaly in children and adults with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:282–90. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199702000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N. Evidence of brain overgrowth in the first year of life in autism. JAMA. 2003;290:337–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Redcay E, Courchesne E. When is the brain enlarged in autism? A meta-analysis of all brain size-reports. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Courchesne E, Mouton PR, Calhoun ME, et al. Neuron number and size in prefrontal cortex of children with autism. JAMA. 2011;306:2001–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Courchesne E, Karns CM, Davis HR, et al. Unusual brain growth patterns in early life in patients with autistic disorder. An MRI study Neurology. 2001;57:245–54. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauman ML. Brief report: Neuroanatomic observations of the brain in pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1996;26:199–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02172012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kemper TL, Bauman ML. The contribution of neuropathologic studies to the understanding of autism. Neurol Clin. 1993;11:175–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Piven J, Nehme E, Simon J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in autism: Measurement of the cerebellum, pons, and fourth ventricle. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;31:491–504. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fombonne E, Roge B, Claverie J, et al. Microcephaly and macrocephaly in autism. J Austism Dev Disord. 1999;29:113–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1023036509476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guerin P, Lyon G, Barthelemy C, et al. Neuropathological study of a case of autistic syndrome with severe mental retardation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1996;38:203–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1996.tb15082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hof PR, Knabe R, Bovier P, et al. Neuropathological observations in a case of autism presenting with self-injury behavior. Acta Neuropath. 1991;82:321–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00308819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Battaglia A. The inv dup (15) or idic (15) syndrome (tetrasomy 15q) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weidmer-Mikhail E, Sheldon S, Ghaziuddin M. Chromosomes in autism and related pervasive developmental disorders: A cytogenetic study. J Intel Disabil Res. 1998;42:8–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolpert CM, Menold MM, Bass MP, et al. Three probands with autistic disorder and isodicentric chromosome 15. Am J Med Genet. 2000a;96:365–72. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000612)96:3<365::aid-ajmg25>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolpert C, Pericak-Vance MA, Abramson RK, et al. Autistic symptoms among children and young adults with isodicentric chromosome 15. Am J Med Genet. 2000b;96:128–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000207)96:1<128::aid-ajmg25>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang B, Crolla JA, Christian SL, et al. Refined molecular characterization of the breakpoints in small inv dup(15) chromosomes. Hum Gen. 1997;99:11–7. doi: 10.1007/s004390050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tuchman R, Moshe SL, Rapin I. Convulsing toward the pathophysiology of autism. Brain Dev. 2009;31:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children: Confirmation of high prevalence. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1133–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gillberg C, Billstedt E, Sundh V, et al. Mortality in autism: A prospective longitudinal community-based study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:352–7. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0883-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ballaban-Gil K, Rapin I, Tuchman R, et al. Longitudinal examination of the behavioral, language, and social changes in a population of adolescents and young adults with autistic disorder. Pediatric Neurol. 1996;15:217–23. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(96)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patja K, Iivanainen M, Vesala H, et al. Life expectancy of people with intellectual disability: A 35-year follow-up study. J Intell Disab Res. 2000;44:591–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shavelle RM, Strauss DJ, Pickett J. Causes of death in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:569–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1013247011483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rakhade SN, Jensen FE. Epileptogenesis in the immature brain: emerging mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:380–91. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wegiel J, Wisniewski T, Chauhan A, et al. Type, topography, and sequelae of neuropathological changes shaping clinical phenotype of autism. In: Chauhan A, Chauhan V, Brown WT, editors. Autism Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Immune Abnormalities. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Voineagu I, Wang X, Johnston P, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature. 2011;474:380–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Krous HF, Chadwick AE, Crandall L, et al. Sudden unexpected death in childhood: A report of 50 cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005;8:307–19. doi: 10.1007/s10024-005-1155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kinney HC, Armstrong DL, Chadwick AE, et al. Sudden death in toddlers associated with developmental abnormalities of the hippocampus: A report of five cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:208–23. doi: 10.2350/06-08-0144.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leestma JE, Kalelkar MB, Teas SS, et al. Sudden unexpected death associated with seizures: Analysis of 66 cases. Epilepsia. 1984;25:84–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1984.tb04159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Donner EJ, Smith CR, Snead OC. Sudden unexpected death in children with epilepsy. Neurology. 2001;57:430–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kinney HC, Chadwick AE, Crandall LA, et al. Sudden death, febrile seizures, and hippocampal and temporal lobe maldevelopment in toddlers: A new entity. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12:455–463. doi: 10.2350/08-09-0542.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Frysinger RC, Harper RM. Cardiac and respiratory correlations with unit discharge in epileptic human temporal lobe. Epilepsia. 1990;31:162–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.1990.tb06301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Blum AS, Ives JR, Goldberger AL, et al. Oxygen desaturations triggered by partial seizures: Implications for cardiopulmonary instability in epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:536–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang TF, Wong TT, Chang KP, et al. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability in children with epilepsy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17:602–6. doi: 10.1007/s003810100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Compressed Mortality File (CMF) compiled from CMF 1968-1988, Series 20, No. 2A 2000, CMF 1989-1998, Series 20, N. 2E 2003 and CMF 1999-2002, Series 20, No. 2H 2004 on CDC WONDER On-line Database ( http://wonder.cdc.gov)

- 91.Purpura DP. Pathobiology of cortical neurons in metabolic and unclassified amentias. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1979;57:43–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benes FM, Davidson J, Bird ED. Quantitative cytoarchitectural studies of the cerebral cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:31–5. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800010033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Galaburda A, Sherman G, Rosen G, et al. Developmental dyslexia: Four consecutive cases with cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:222–33. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.