Abstract

Purpose

Enzyme replacement therapy in infants with Pompe disease prolongs survival, decreases cardiomegaly, and improves muscle function. Because ectopy has been previously described in these patients, we sought to determine the prevalence and types of arrhythmias.

Methods

Thirty-eight children with infantile Pompe disease received enzyme replacement therapy in two open-label, multicenter, international, clinical trials. Data were reviewed on a retrospective basis. The corrected QT interval, ejection fraction, and indexed left ventricular mass were measured on a scheduled basis from electrocardiograms and echocardiograms. Arrhythmias were identified and characterized from electrocardiograms, ambulatory electrocardiograms, and point-of-care monitoring. Electrocardiogram and echocardiogram measurements were compared in children with and without arrhythmias.

Results

Seven children (18%) experienced arrhythmias. The QT interval, ejection fraction, indexed left ventricular mass, and rate of reduction of indexed left ventricular mass were not statistically different in those seven versus the other 31 children. Two children with life-threatening arrhythmias had among the highest combined baseline maximum indexed left ventricular mass and QT interval. Their arrhythmias occurred during severe metabolic stress from noncardiac illness.

Conclusions

There was a high incidence of arrhythmias in our cohort. The relationship of arrhythmias with enzyme replacement therapy, myocardial fibrosis, or simply longer survival is unknown. Therefore, further characterization of specific arrhythmia risk factors and continued vigilance regarding screening for arrhythmias in children receiving enzyme replacement therapy is warranted.

Keywords: Pompe disease, glycogen storage disease type II, arrhythmias, enzyme replacement therapy, cardiomyopathy

Pompe disease or glycogen storage disease type II is an autosomal recessive disorder due to lysosomal deficiency of acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA). Deficiency of this enzyme results in the excessive accumulation of glycogen within the lysosomes of many tissues including cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle cells. Infantile Pompe disease has the most severe presentation with minimal or no residual enzyme activity.1, 2 Infantile Pompe disease is uniformly fatal, usually by 1 year of age, if untreated.3, 4

In this disease, the specialized cardiac conduction tissue is also affected by glycogen accumulation, resulting in the characteristic electrocardiographic finding of a shortened PR interval. 5 Occasionally, the shortened PR interval may be due to the presence of a true atrioventricular (AV) accessory pathway, demonstrating the Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern; these children may be at an increased risk for supraventricular tachyarrhythmias.6–8 In addition, the ubiquitous electrocardiographic findings of extreme left ventricular hypertrophy and increased QT dispersion in these children may represent risk factors for sudden arrhythmic death from ventricular tachyarrhythmias.9

Clinical trials of enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) using recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase (rhGAA) have demonstrated prolonged overall survival in infants and children with Pompe disease. A reversal of cardiomyopathy has been noted in the majority of patients, and a subset of patients have achieved motor milestones such as the ability to sit, walk, and run.10–15 Alglucosidase alfa (Myozyme), rhGAA manufactured and distributed by Genzyme Corporation for ERT, has been approved for use as a treatment for Pompe disease in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and in Europe by the European Medicines Agency.16, 17

Children who receive ERT for infantile Pompe disease manifest electrocardiographic changes, including an increase in the PR interval and a decrease in both the QT dispersion and left ventricular voltage.9 Despite these improvements, increased ventricular ectopy has been observed in some treated infants,18 and cardiopulmonary arrest soon after the induction of general anesthesia has been observed in others.19, 20 With this background, we sought to determine the prevalence and types of arrhythmias and their associations to electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings in children with infantile Pompe disease undergoing treatment with ERT.

METHODS

A total of 39 children with infantile Pompe disease were enrolled in two open-label, multicenter, international, clinical trials (numbered NCT00059280 and NCT00053573) exploring the safety and efficacy of ERT from 2001 to 2005. All children had a confirmed diagnosis of infantile Pompe disease with skin fibroblast GAA activity <1% of normal, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (left ventricular mass index ≥65 g/m2 by echocardiogram) and onset of symptoms in the first year of life. Alglucosidase alfa containing rhGAA produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells was supplied by Genzyme Corporation (Cambridge, MA). All participating centers obtained institutional review board approval at their respective institutions and informed consent was obtained from each patient's parent/guardian.

Data were reviewed on a retrospective basis. Electrocardiograms (ECG) and echocardiograms were obtained on each child at baseline and at 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 52, 64, and 78 weeks of ERT and interpreted at a central laboratory. Measured data included corrected QT interval (QTc), ejection fraction (EF), and indexed left ventricular mass (LVMi). Arrhythmias were documented from ECGs, ambulatory ECGs, and point-of-care monitoring through review of FDA Form 3500A (Medwatch) reports, a safety information and adverse event reporting system of the US FDA. Arrhythmias were defined as being possibly clinically important (nonsustained supraventriculartachycardia (SVT), atrial, or ventricular premature beats), definitely clinically important (sustained SVT), and life-threatening (ventricular tachycardia [VT] or fibrillation [VF]). For purposes of this study, nonsustained SVT was defined as occurring for <5 seconds in duration. This is based on the apriori belief that these infants would be unusually vulnerable to the effects of severe abbreviation of ventricular diastole, as would result from longer episodes of SVT. VT was defined as three or more repetitive ventricular events at >10% faster than the current sinus rate and not due to a supraventricular focus or circuit. Other arrhythmias were defined according to standard definitions. Electrocardiographic and echocardiographic measurements from children with an arrhythmia occurrence were compared with children who had not experienced an arrhythmia. Ambulatory ECGs were not performed on a routine basis in this cohort but were performed when clinically indicated.

Reported P values are two-tailed and nonparametric methods were used, e.g., Wilcoxon rank sum test. Analyses were conducted using STATA 10.0 (College Station, TX). P _ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 38 children received ERT. Their demographics including gender, ethnicity, age at entry into the study, and duration of ERT are presented in Table 1. One patient was enrolled but died from a cardiac arrhythmia associated with anesthesia induction before the initiation of therapy. A total of seven children (18%) receiving treatment with ERT experienced arrhythmias. The type of arrhythmia, age at ERT initiation, age at arrhythmia onset, duration of ERT at time of arrhythmia, and results of cardiac tests from these seven children are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive demographic features and comparison of cardiac measurements from patients with and without arrhythmias

| Arrhythmia (n = 7) | No arrhythmia (n = 31) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3 | 17 | |

| Female | 4 | 14 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 2 | 20 | |

| Black | 0 | 6 | |

| Asian | 4 | 1 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 0 | 3 | |

| Age ERT initiateda | 7 (6–13) | 8 (1–43) | |

| Duration of ERT at last follow-upa | 19.5 (12–23) | 12 (1–26) |

| P | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum QTc (ms) | 444 (439, 476) | 444 (437, 450) | 0.20 |

| Maximum LVMi (g/m2) | 180 (163, 269) | 206 (111, 241) | 0.69 |

| Minimum EF (%) | 33 (21, 45) | 42 (30, 54) | 0.20 |

| Maximum decrease in LVMi (g/m2/wk) | 3.3 (0.7, 6.6) | 5.2 (2.5, 7.1) | 0.25 |

Measurements displayed as median (25%, 75%).

Age and duration is in months displayed as median (range).

Table 2.

Description of patients with arrhythmias

| Patient | Arrhythmia | Category | Age ERT onset (mos) | Age arrhythmia onset (mos) | Duration of ERT at arrhythmia onset (mos) | Minimum EF% | Maximum QTc (ms) | Maximum LVMi (g/m2) | Maximum rate of decrease in LVMi (g/m2/wk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SVT, nonsustained | PCI | 6 | 17 | 11 | 45 | 439 | 180 | 13.1 |

| 2 | VPB | PCI | 7 | 10 | 3 | 33 | 444 | 163 | 6.6 |

| 3 | Atrial bigeminy | PCI | 6 | 7 | 1 | 21 | 438 | 221 | 0.7 |

| 4 | SVT, VT | DCI | 6 | 14 | 8 | 57 | 444 | 163 | 1.3 |

| 5 | AVRT | DCI | 6 | 18 | 12 | 27 | 476 | 179 | 4.7 |

| 6 | VF | LT | 6 | 19 | 13 | 36 | 500 | 302 | 3.3 |

| 7 | VF | LT | 12 | 17 | 5 | 21 | 470 | 269 | 3.5 |

AVRT, atrioventricular reciprocating tachycardia; DCI, definitely clinically important; EF, ejection fraction; LT, life threatening; LVMi, indexed left ventricular mass; PCI, possibly clinically important; QTc, correctedQTinterval; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VPB, ventricular premature beats; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Patient 1 experienced multiple episodes of brief, nonsustained SVT, atrial bigeminy and trigeminy which were demonstrated on ambulatory ECG monitoring. These episodes decreased significantly with the administration of propanolol. Occasional ventricular premature beats were initially noted in Patient 2 preoperatively and subsequently during surgery for a muscle biopsy and gastrostomy tube placement at Week 12 of the study. The frequency of the ventricular premature beats increased postoperatively, prompting treatment with an intravenous lidocaine infusion. This was eventually transitioned to enteral mexiletine. The frequency of ventricular premature beats remained decreased on enteral therapy by ambulatory ECG. Patient 3 received digoxin for episodes of intermittent atrial bigeminy. At the initiation of a bronchoscopy under general anesthesia, Patient 4 developed SVT followed by VT and bradycardia. The infant was successfully resuscitated with epinephrine, atropine, and approximately 1 minute of chest compressions. In this patient, anesthesia had been started with ketamine, followed by sevoflurane and succinylcholine before bronchoscopy. The infant recovered without sequelae. Patient 5 experienced multiple episodes of the AV reciprocating tachycardia form of SVT. The initial episode occurred at Week 52 of treatment with a heart rate of 280 beats per minute and associated symptoms of irritability and decreased appetite. SVT recurrence ultimately required high dose propanolol for clinical control. Follow-up ambulatory ECG in this patient demonstrated no SVT recurrence on high dose propanolol. Patient 6 had frequent episodes of pneumonia requiring multiple prolonged intubations. At approximately Week 55 of ERT, shortly after extubation during one of these pneumonias, the patient experienced increased sputum production and desaturation. Patient was reintubated, but developed sinus bradycardia and then VF in the presence of severe metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia. Resuscitation was unsuccessful. Patient 7 had recently completed antibiotic therapy for Klebsiella septicemia when she was readmitted for lethargy, hyperthermia, dehydration, and mild renal insufficiency. Two days later, and without clinical improvement, she experienced the sudden onset of VF, followed by progressive bradycardia and death. Resuscitation was not attempted. Blood and urine cultures remained negative. It should be noted, in this patient ventricular hypokinesia and severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy had remained unchanged from the onset of ERT until death.

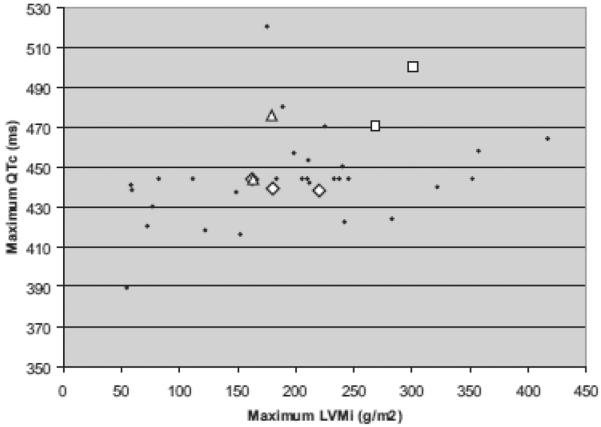

Because associations of cardiac tachyarrhythmias or sudden death with certain ECG and echocardiographic measurements have been established in other diseases, (including maximum QTc,21–23 maximum LVMi,24, 25 and minimum left ventricular minimum left ventricular EF26–28) we evaluated these parameters in our cohort, comparing those with and without arrhythmias (Table 1). The differences between the two groups were not statistically significant. A trend toward a lower minimum EF was observed in the arrhythmia group. The two children (Patients 6 and 7) with fatal arrhythmias seemed to have higher baseline combined maximum LVMi and maximum QTc, two known risk factors for sudden death, when compared with the other children (Fig. 1). However, the LVMi that was measured months before death in Patient 6 had decreased to 119 g/m2, and the QTc that was measured 1 month before death in Patient 7 was normal at 388 milliseconds.

Figure 1.

Combined maximum QTc and maximum LVMi for each patient by arrhythmia category. Circle, no arrhythmia; diamond, possibly clinically important; triangle, definitely clinically important; square, life-threatening.

Discussion

Infantile Pompe disease, if untreated, is rapidly fatal. Affected infants present in the first months of life with hypotonia, generalized weakness, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with progression to death secondary to respiratory muscle failure.

ERT with recombinant human GAA in infantile Pompe disease has resulted in a dramatic change in the clinical course in affected children with prolonged survival, restoration and stability of motor function, and improvement of cardiomyopathy.10–15 In addition, there are substantial improvements in the ECG including a decrease in left ventricular voltage, an increased PR interval, and a shortening of QT dispersion.9 It has been postulated that the reduction of glycogen within the conduction system and myocardium results in these changes. Despite significant improvements in cardiomyopathy and the conduction system in infants receiving ERT, there was an unexpectedly high incidence of arrhythmias (18%) in our cohort. To understand the etiology of arrhythmogeneisis in individuals with Pompe disease, other types of glycogen or lysosomal storage disorders with cardiomyopathy may be considered. Severe cardiac hypertrophy and conduction system disease are common features of Danon disease caused by mutations of the lysosome associated membrane protein 2 gene. Mutations in the gene for AMP-activated protein kinase γ2 variably results in Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern, progressive conduction system disease, and ventricular hypertrophy. Both of these diseases result in accumulation of lysosomal or cytosolic glycogen leading to left ventricular hypertrophy.29–31 Studies involving the transgenic mouse model of AMP-activated protein kinase γ2 have provided an anatomic explanation for the cause of Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome in glycogen storage cardiomyopathy.30, 32, 33 Cardiac histopathology in this model demonstrated disruption of the annulus fibrosis, the structure which normally insulates the ventricles from inappropriate conduction from the atria, by glycogen engorged myocytes.30 Electrophysiological testing has demonstrated alternative AV conduction pathways consistent with Wolff-Parkinson-White.

Cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmias are also found in Fabry disease, a lysosomal storage disorder resulting in the intracellular accumulation of sphingolipid. In this disorder, histologic findings of myocardial fibrosis have been correlated with findings of late gadolinium enhancement by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.34 Patients with findings of late enhancement also have significantly higher left ventricular masses than those who do not. However, ERT in these patients does not significantly reduce ventricular mass and late enhancement on follow-up imaging actually increases.35

Postmortem analyses of infants with Pompe disease before the advent of ERT revealed excessive amounts of connective tissue at the approaches to theAVnode, theAVnode itself, and the penetrating AV bundle. These findings would be expected to potentiate pathologic radyarrhythmias. Surprisingly, bradycardias were not noted in our children as primary events. In addition, focal necrosis, hemorrhage and fibrosis have been seen in the peripheral Purkinje cells in these postmortem studies. 5 It is possible that excessive connective tissue develops during glycogen accumulation early in the disease process which persists despite clearance of glycogen stores with ERT. This scarring could lead to myocardial perfusion abnormalities or represent a direct substrate for ventricular arrhythmias, similar to the pathophysiology seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.36 Myocardial fibrosis, which is characteristic of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, has also been implicated in causing spatial dispersion of the cardiac impulse supporting reentrant arrhythmias, although the exact mechanism is unknown.36–38 Further study of the cardiac histopathology in Pompe disease after long-term ERT is needed.

Risk factors for sudden death in children having any of a variety of structural heart diseases include left ventricular hypertrophy,24, 25 prolonged QTc interval,21–23 reduced EF,26–28 increased QT dispersion,39, 40 and reduced measures of heart rate variability.41, 42 Among those measurements available in our cohort of children studied, no values were observed which were statistically more exceptional in those children having arrhythmias than in those who did not. Increased ventricular ectopy has been previously reported in children receiving ERT for infantile Pompe disease during times of rapid decreases in left ventricular mass; hence, the maximum rate of decrease of left ventricular mass was also considered.18 Interestingly, a lower rate of mass reduction was associated with a modest trend toward arrhythmogeneisis (Table 1). The observed trend of lower EF in the arrhythmia group (Table 2) requires substantiation by a larger patient population.

Fatal events occurred during times of metabolic stress in two children (Patients 6 and 7), highlighting the importance of cardiovascular and pulmonary attention during invasive procedures and intercurrent illnesses. Anesthesia induction with its associated vasodilatation, afterload reduction and therefore potential for reduced coronary perfusion could contribute to the development of arrhythmias. This has prompted the recommendation to avoid anesthetic agents with vasodilatory effects such as propofol or high concentrations of sevoflurane but, instead, use an agent such as ketamine to better support coronary perfusion pressure.19, 20 Our study was limited by the small sample size and its retrospective design; however, 7 of 38 (18%) children treated with ERT developed arrhythmias. The relationship of arrhythmias with ERT, myocardial fibrosis, or simply longer survival could not be ascertained from this experience. We therefore believe continued routine screening for arrhythmias in patients receiving ERT is warranted. This may be especially relevant to those infants with more severe baseline cardiac phenotypes, as manifest by markedly elevated LVMi and prolonged QTc interval. It is possible that subclinical arrhythmias are more prevalent in this patient group than was realized by this experience. Periodic ambulatory rhythm monitoring may be considered for these patients to help answer this question.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Dr. Kishnani has received research/grant support from Genzyme Corporation and is a member of the Pompe Disease Advisory Board. rhGAA, in the form of Genzyme's product, Myozyme™, is now approved by the US FDA and the European Union as therapy for Pompe disease. Duke University and inventors for the method of treatment and predecessors of the cell lines used to generate the enzyme (rhGAA) used in various clinical trials receive royalty payments pursuant to the University's Policy on Inventions, Patents and Technology. Dr. Benjamin received support from NICHD 1U10-HD45962-05.

References

- 1.Kishnani PS, Howell RR. Pompe disease in infants and children. J Pediatr. 2004;144:S35–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirshhorn R. Glycogen storage disease type ii: Acid alpha-glucosidase deficiency. McGraw Hill; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishnani PS, Hwu WL, Mandel H, Nicolino M, Yong F, Corzo D. A retrospective, multinational, multicenter study on the natural history of infantile-onset pompe disease. J Pediatr. 2006;148:671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Hout HM, Hop W, van Diggelen OP, Smeitink JA, Smit GP, Poll-The BT, Bakker HD, Loonen MC, de Klerk JB, Reuser AJ, van der Ploeg AT. The natural course of infantile pompe's disease: 20 original cases compared with 133 cases from the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;112:332–340. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharati S, Serratto M, DuBrow I, Paul MH, Swiryn S, Miller RA, Rosen K, Lev M. The conduction system in pompe's disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 1982;2:25–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02265613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulkley BH, Hutchins GM. Pompe's disease presenting as hypertrophic myocardiopathy with wolff-parkinson-white syndrome. Am Heart J. 1978;96:246–252. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(78)90093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francesconi M, Auff E, Ursin C, Sluga E. wpw syndrome combined with av block 2 in an adult with glycogenosis (type ii) Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1982;94:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabarki B, Mahdhaoui A, Yacoub M, Selmi H, Mahdhaoui N, Bouraoui H, Ernez S, Jridi G, Ammar H, Essoussi AS. familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with wolff-parkinson-white syndrome revealing type ii glycogenosis. Arch Pediatr. 2002;9:697–700. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(01)00968-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansong AK, Li JS, Nozik-Grayck E. Electrocardiographic response to enzyme replacement therapy for pompe disease. Genet Med. 2006;8:297–301. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000195896.04069.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishnani PS, Corzo D, Nicolino M. Recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase: Major clinical benefits in infantile-onset pompe disease. Neurology. 2007;68:99–109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251268.41188.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amalfitano A, Bengur AR, Morse RP. Recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase enzyme therapy for infantile glycogen storage disease type ii: Results of a phase i/ii clinical trial. Genet Med. 2001;3:132–138. doi: 10.109700125817-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Hout JM, Reuser AJ, de Klerk JB. Enzyme therapy for pompe disease with recombinant human alpha-glucosidase from rabbit milk. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24:266–274. doi: 10.1023/a:1010383421286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van den Hout JM, Kamphoven JH, Winkel LP. Long-term intravenous treatment of pompe disease with recombinant human alpha-glucosidase from milk. Pediatrics. 2004;113:448–457. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinge L, Straub V, Neudorf U. Safety and efficacy of recombinant acid alpha-glucosidase (rhgaa) in patients with classical infantile pompe disease: Results of a phase ii clinical trial. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishnani PS, Nicolino M, Voit T. Chinese hamster ovary cell-derived recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase in infantile-onset pompe disease. J Pediatr. 2006;149:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fda approves first treatment for pompe's disease. 2006.

- 17.European medicines agency: Committee for medicinal products for human use. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Cook AL, Kishnani PS, Carboni MP. Ambulatory electrocardiogram analysis in infants treated with recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase enzyme replacement therapy for pompe disease. Genet Med. 2006;8:313–317. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000217786.79173.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang LY, Ross AK, Li JS. Cardiac arrhythmias following anesthesia induction in infantile-onset pompe disease: A case series. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17:738–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2007.02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ing RJ, Cook DR, Bengur RA. Anaesthetic management of infants with glycogen storage disease type ii: A physiological approach. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14:514–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss AJ. Measurement of the qt interval and the risk associated with qtc interval prolongation: A review. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:23B–25B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90036-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garson A, Jr., Dick M, II, Fournier A. The long qt syndrome in children. An international study of 287 patients. Circulation. 1993;87:1866–1872. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent GM. Long qt syndrome. Cardiol Clin. 2000;18:309–325. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maki S, Ikeda H, Muro A. Predictors of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:774–778. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabo P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1778–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romeo F, Cianfrocca C, Pelliccia F, Colloridi V, Cristofani R, Reale R. Long-term prognosis in children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An analysis of 37 patients aged less than or equal to 14 years at diagnosis. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13:101–107. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960130208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimm W, Christ M, Bach J, Muller HH. Noninvasive arrhythmia risk stratification in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: Results of the marburg cardiomyopathy study. Circulation. 2003;108:2883–2891. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100721.52503.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azevedo VM, Santos MA, Albanesi Filho FM, Castier MB, Tura BR, Amino JG. Outcome factors of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in children[mdash]a long-term follow-up review. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:175–184. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arad M, Maron BJ, Gorham JM. Glycogen storage diseases presenting as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:362–372. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arad M, Moskowitz IP, Patel VV. Transgenic mice overexpressing mutant prkag2 define the cause of wolff-parkinson-white syndrome in glycogen storage cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;107:2850–2856. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000075270.13497.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charron P, Villard E, Sebillon P. Danon's disease as a cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A systematic survey. Heart. 2004;90:842–846. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.029504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel VV, Arad M, Moskowitz IP. Electrophysiologic characterization and postnatal development of ventricular pre-excitation in a mouse model of cardiac hypertrophy and wolff-parkinson-white syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:942–951. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidhu JS, Rajawat YS, Rami TG. Transgenic mouse model of ventricular preexcitation and atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia induced by an amp-activated protein kinase loss-of-function mutation responsible for wolff-parkinson-white syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:21–29. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151291.32974.D5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moon J, Sheppard M, Reed E, Lee P, Elliott PM, Pannell DJ. The histological basis of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in a patient with anderson-fabry disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8:479–482. doi: 10.1080/10976640600605002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beer M, Weidemann F, Breunig F. Impact of enzyme replacement therapy on cardiac morphology and function and late enhancement in fabry's cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1515–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shirani J, Pick R, Roberts WC, Maron BJ. Morphology and significance of the left ventricular collagen network in young patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yi G, Elliott P, McKenna WJ. Qt dispersion and risk factors for sudden cardiac death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1514–1519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00696-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dritsas A, Sbarouni E, Gilligan D, Nihoyannopoulos P, Oakley CM. Qt-interval abnormalities in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15:739–742. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960151010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun ZH, Happonen JM, Bennhagen R. Increased qt dispersion and loss of sinus rhythm as risk factors for late sudden death after mustard or senning procedures for transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Day CP, McComb JM, Campbell RW. Qt dispersion: An indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long qt intervals. Br Heart J. 1990;63:342–344. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.6.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonaduce D, Petretta M, Marciano F. Independent and incremental prognostic value of heart rate variability in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 1999;138:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brouwer J, van Veldhuisen DJ, Man in 't Veld AJ. Prognostic value of heart rate variability during long-term follow-up in patients with mild to moderate heart failure. The dutch ibopamine multicenter trial study group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]