Abstract

Purpose

The Head and Neck Intergroup conducted a Phase III randomized trial to determine whether the addition weekly cisplatin to daily radiation therapy (RT) would improve survival in patients with unresectable squamous cell head-and-neck carcinoma.

Methods and Materials

Eligible patients were randomized to RT (70 Gy at 1.8–2 Gy/day) or to the identical RT with weekly cisplatin dosed at 20 mg/m2. Failure-free survival (FFS) and overall survival (OS) curves were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log rank test.

Results

Between 1982 and 1987, 371 patients were accrued, and 308 patients were found eligible for analysis. Median follow-up was 62 months. The median FFS was 6.5 and 7.2 months for the RT and RT + cisplatin groups, respectively (p = 0.30). The p value for the treatment difference was p = 0.096 in multivariate modeling of FFS (compared to a p = 0.30 in univariate analysis). Expected acute toxicities were significantly increased with the addition of cisplatin except for in-field RT toxicities. Late toxicities were not significantly different except for significantly more esophageal (9% vs. 3%, p = 0.03) and laryngeal (11% vs. 4%, p = 0.05) late toxicities in the RT + cisplatin group.

Conclusion

The addition of concurrent weekly cisplatin at 20 mg/m2 to daily radiation did not improve survival, although there was evidence of activity. Low-dose weekly cisplatin seems to have modest tumor radiosensitization but can increase the risk of late swallowing complications.

Keywords: Randomized, Cisplatin, Unresectable, Weekly cisplatin, Late complications

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 20 years, multiple randomized trials (1–4) and meta-analyses (5, 6) have supported the conclusion that radiotherapy (RT) intensification improves local-regional disease control and survival in the management of locally advanced head-and-neck squamous cell carcinomas. This may be achieved with altered fractionated RT (2) or with the addition of concurrent chemotherapy (1, 3). Not only is the spectrum and magnitude of acute toxicities increased, but it is now clear that treatment intensification increases late swallowing complications (7–9). No randomized trials have defined the optimal treatment intensive regimen, although meta-analysis and consensus expert opinion have favored platinum chemoradiation, typically with cisplatin dosed at 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks (10).

Now that the improved prognosis of human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal carcinomas has become accepted (11, 12), attention has focused on developing risk-adapted deintensified therapies in the hope of reducing the long-term toxicities of concurrent chemoradiation strategies in this patient population. This issue is also relevant in patients of advanced age. Meta-analysis has demonstrated that the survival gains achieved with treatment intensification (5, 6) are attenuated with advancing age, which is also an independent risk factor for late swallowing toxicity when these patients are treated with chemoradiation (7, 8).

These considerations have placed a greater emphasis on the potential activity of alternative platinum chemoradiation approaches in the hope of establishing regimens with improved toxicity and tolerability profiles. Weekly cisplatin schedules have been proposed not only for improved tolerability but to reduce both acute and late toxicities. This practice has been based on little evidence guiding the appropriate weekly dose of cisplatin that should be used. We report the results of a previously completed and unreported randomized trial conducted through the Head and Neck Intergroup, asking whether or not weekly cisplatin at a dose of 20 mg/m2/week was effective.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

Study eligibility included patients with biopsy-proven head-and-neck squamous cell or undifferentiated carcinoma, technically unresectable American Joint Committee on Cancer 1980 clinical Stage III or IV with no distant metastasis. This trial, to our knowledge, represented the first clinical trial that established a systematic criterion for unresectability to ensure a homogeneous study population. The criteria for unresectability were identical to E1392 (13). All anatomic sites of the head and neck were included. This included nasopharyngeal carcinomas but restricted to T3/4 or N2/3 disease only. At the initiation of the trial, from November 1982 to August 1983, patients with an incomplete resection and gross residual tumor were permitted to enroll in the absence of documented distant disease. After August 1983, these patients were excluded.

Eligibility also required an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0–3 and adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. Exclusion criteria included existing cardiac conditions, pregnancy or lactation in women, prior treatment with RT or chemotherapy, and any prior or synchronous malignancy.

This study was conducted under the auspices of ECOG, Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG), and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and was approved by the individual institutional review boards of all participating institutions.

Randomization

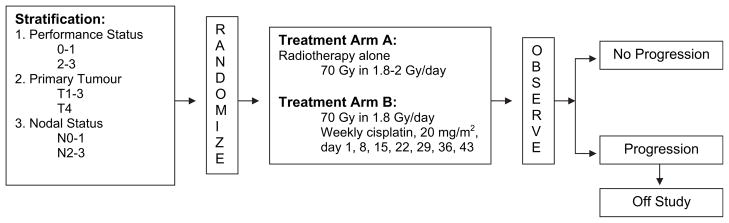

On study entry, eligible patients were stratified by PS (0–1 vs. 2–3), primary tumor stage (T1–3 vs. T4) and nodal stage (N0–1 vs. N2–3). Patients were randomized (ECOG central randomization desk) using permuted blocks within strata using dynamic institutional balancing (14). Patients were assigned to once daily RT or to RT plus concomitant cisplatin dosed at 20 mg/m2 per week (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study schema.

Radiation

Treatment was delivered with either cobalt teletherapy or a linear accelerator (up to 6 MV) with a standard three-field bilateral neck beam arrangement. The primary lesion was treated with a generous margin, typically 2–3 cm. Each field was treated daily, 5 days a week. Off spinal cord field reductions were used with additional field reductions left to the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. The prescribed dose to the primary lesion and involved nodal disease was 68–76 Gy. Uninvolved areas were electively treated to 50–55 Gy. The low anterior cervical neck was prescribed 50 Gy (at Dmax) unless gross disease was initially present, and the dose was then boosted to 70 Gy. The daily fraction was 1.8–2 Gy and 1.8 Gy in the RT and RT + cisplatin arms, respectively.

Chemotherapy

In the RT + cisplatin arm, concurrent single-agent cisplatin, 20 mg/m2 intravenously, was administered on Days 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 36, and 43 of the radiation schedule. Cisplatin was administered within 2 hours after the scheduled RT. Aggressive hydration and antiemetic therapy was used with the cisplatin administration. Cisplatin dose modifications were defined for nadir or treatment-day leukopenia or thrombocytopenia and for any nephrotoxicity. Dose modification for mucositis or any local-regional complications was left to the discretion of the treating physician.

Endpoint definition

At the time of the study, complete response (CR)was defined as complete disappearance of all detectable tumor lasting for at least 4 weeks. Partial response (PR) was defined as a reduction of at least 50% of the product of the longest perpendicular diameters of the tumor with no new area of malignant disease appearing for at least 4 weeks. Stable disease was defined as less than 25% increase in measurable disease with no significant deterioration in PS by greater than one level caused by disease progression. Disease progression was defined as an increase in a measurable lesion by greater than 25% or the appearance of new areas of malignancy or deterioration in PS resulting from to malignancy. Disease response was assessed weekly during radiation, then monthly during the first year of follow-up, and then every 3 months thereafter.

The major endpoint of the study was failure-free survival (FFS) measured from the date of randomization to the first evidence of progression, relapse, or death. Additional endpoints included the overall survival (OS) measured from the date of the randomization to the date of death or the last date the patient was known to be alive. Secondary endpoints for analysis included tumor response, acute toxicities, and late toxicities as measured on the Radiotherapy Long Term Follow-up Form. Two additional acute effects, laryngeal edema and nutritional toxicity, were also evaluated using the Head and Neck Radiation Therapy Form.

Statistical analysis

The accrual goal for this study was 300 patients (150 patients in each arm), which was needed to detect an increase of 50% in median survival between the two arms with an 80% power using a one-sided log-rank test with an overall Type I error of 0.05. This was based on an expected median survival of 13 months in the control arm. An accrual rate of 75 patients/year was projected. The FFS and OS curves were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log rank test. The proportional hazards model was used to adjust for variables simultaneously when assessing FFS or OS. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare a dichotomous endpoint. For ordered contingency tables (i.e., toxicity grade by treatment), the two-sample Wilcoxan midrank test was used. The logistic model was used to adjust for one or more explanatory variables simultaneously when assessing response. For both the logistic and the proportional hazards model, a stepwise regression approach was used. The original analysis design was performed on an as-treated basis.

RESULTS

From November 23, 1982, to June 12, 1987, a total of 371 patients were accrued to the study. The number of patients accrued from ECOG, RTOG, and SWOG was 173, 114, and 84 patients, respectively. The study was administered and analyzed by ECOG. Of the 371 patients randomized, 63 (17%) were excluded from the primary analyses. Eighteen patients did not receive protocol therapy, and an additional 45 patients were found to be ineligible. Reasons included findings of inadequate hematologic and renal function, resectable disease, nonsquamous histology, and a second primary malignancy with or without metastases. A total of 308 (83% of the total randomized) was eligible for analysis. Table 1 summarizes the number of eligible and analyzable patients. Median follow-up for these patients was 62 months.

Table 1.

Study population

| Eligibility | Radiation | Radiation + cisplatin (20 mg/m2/wk) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized | 185 | 186 | 371 |

| Excluded | 8* | 10† | 18 |

| Ineligible | 18 | 27 | 45 |

| Eligible for analysis | 159 | 149 | 308 |

Patient refusal (n = 5), died before treatment (n = 1), received nonprotocol treatment (n = 1), could not be positioned for radiation therapy (n = 1).

Patient refusal (n = 4), died before treatment (n = 3), elected non-protocol treatment (n = 1), decreased serum creatinine and creatinine clearance (n = 1).

The clinical characteristics of the 308 analyzable patients are presented in Table 2. There were some imbalances with the RT + cisplatin group: a higher number of patients with age >65, weight loss ≥10% in the previous 6 months, >40 pack-years exposure to smoking, well or moderate cell differentiation, and nonnasopharyngeal primary tumors. These imbalances contributed to a bias against the RT + cisplatin treatment group with the as-treated analysis.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Radiation (n = 159) | Radiation + cisplatin (20 mg/m2/wk) (n = 149) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| <65 | 114 (72%) | 99 (64%) |

| ≥65 | 45 (28%) | 54 (36%) |

| Median | 60 | 61 |

| Range | (19–85) | (20–81) |

| Sex | ||

| M | 133 (84%) | 117 (79%) |

| F | 26 (16%) | 32 (21%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 122 (77%) | 115 (77%) |

| Nonwhite | 37 (23%) | 34 (23%) |

| Weight loss (previous 6 mo) | ||

| 0% | 46 (29%) | 46 (31%) |

| 1–9% | 38 (24%) | 26 (17%) |

| ≥10% | 63 (40%) | 70 (47%) |

| Unknown | 12 (8%) | 7 (5%) |

| Smoking history | ||

| Never | 16 (10%) | 6 (4%) |

| Pipe or cigar only | 7 (4%) | 11 (7%) |

| Cigarette: <20 pack/y | 7 (4%) | 9 (6%) |

| Cigarette: 20–40 pack/y | 47 (30%) | 38 (26%) |

| Cigarette: >40 pack/y | 78 (49%) | 80 (54%) |

| Unknown | 4 (3%) | 5 (3%) |

| Performance status | ||

| 0 | 42 (26%) | 33 (22%) |

| 1 | 81 (51%) | 87 (58%) |

| 2 | 29 (18%) | 23 (15%) |

| 3 | 7 (4%) | 6 (4%) |

| Cell differentiation | ||

| Well | 16 (10%) | 28 (19%) |

| Moderate | 79 (50%) | 80 (54%) |

| Poor/undifferentiated | 48 (30%) | 32 (21%) |

| Unknown | 16 (10%) | 9 (6%) |

| T stage | ||

| 0 | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1 | 5 (3%) | 3 (2%) |

| 2 | 14 (9%) | 12 (8%) |

| 3 | 49 (31%) | 45 (30%) |

| 4 | 89 (56%) | 89 (60%) |

| N stage | ||

| 0 | 39 (25%) | 32 (22%) |

| 1 | 17 (11%) | 24 (16%) |

| 2 | 32 (20%) | 27 (18%) |

| 3 | 71 (45%) | 66 (44%) |

| Stage | ||

| III | 23 (14%) | 21 (14%) |

| IV excluding T4 N3 | 97 (61%) | 89 (60%) |

| T4 N3 | 39 (25%) | 39 (26%) |

| Prior surgery | ||

| No | 121 (76%) | 108 (72%) |

| Yes | 38 (24%) | 41 (28%) |

| Primary site | ||

| Nasopharynx | 25 (16%) | 16 (11%) |

| Oral cavity | 43 (27%) | 51 (34%) |

| Oropharynx | 48 (30%) | 37 (25%) |

| Larynx | 7 (4%) | 14 (9%) |

| Hypopharynx | 30 (19%) | 27 (18%) |

| Other | 6 (4%) | 4 (3%) |

Overall, the addition of weekly cisplatin did not significantly increase both FFS and OS. The Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of being failure free (FFS) and remaining alive (OS) are presented in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The median FFS was 6.5 and 7.2 months for the RT and RT + cisplatin groups, respectively (p = 0.30). An intent-to-treat analysis demonstrated no difference (data not shown). Univariate analysis demonstrated that a poorer FFS was associated with several factors: more smoking exposure (p = 0.002), greater alcohol consumption (p = .003), ECOG PS 2–4 (p < 0.001), better cell differentiation (p = 0.007), higher stage (p = 0.003), and nonnasopharynx primary site (p = 0.002). The final multivariate analysis is summarized in Table 3. The p value for the treatment difference was p = 0.096 in this model (compared to p = 0.30 in the univariate analysis).

Fig. 2.

Failure-free survival by treatment.

Fig. 3.

Overall survival by treatment.

Table 3.

Multivariate proportional hazards model for failure-free survival (FFS) and overall survival (OS)

| Covariate | Unfavorable category | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Proportional hazards model for FFS | ||

| Treatment | Radiation | 0.096 |

| Performance status | 2, 3 | 0.0002 |

| Alcohol | Yes | 0.02 |

| Site | Non-nasopharynx | 0.003 |

| Stage | T4 N3 | 0.009 |

| Proportional hazards model for OS | ||

| Treatment | Radiation + cisplatin (20 mg/m2/wk) | 0.60 |

| Performance status | 2, 3 | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | Yes | <0.001 |

| Sex | Male | 0.002 |

| Age (y) | ≥65 | 0.005 |

The median survival was 13.3 and 11.8 months for the RT and RT + cisplatin groups, respectively (p = 0.81), also not significantly different with an intent-to-treat analysis (data not shown). Univariate analysis demonstrated that a poorer OS was associated with several factors: white race (p = 0.04), greater smoking exposure (p = 0.002), greater alcohol consumption (p < 0.001), ECOG PS 2–4 (p < 0.003), better cell differentiation (p = 0.034), higher stage (p = 0.021), and nonnasopharynx primary site (p = 0.001). Multivariate analysis demonstrated no significant treatment effect (p = 0.60) (Table 3).

Tumor response reported by treatment group is summarized in Table 4. Overall, 39% of patients had a CR, and 34% achieved a PR, for a total response rate of 73%. There was no difference in the CR rate by treatment group (p = 0.64). There was a significant difference in the overall response rate by treatment group in favor of the RT + cisplatin group (79% vs. 67%, p = 0.03). Factors associated with a poorer overall response rate (CR + PR) by univariate analysis included worse PS (i.e., ECOG PS 1–3, p = 0.02) and no prior surgery (p = 0.03). Multivariate modeling demonstrated that treatment (RT + cisplatin, p = 0.03), better PS (i.e., ECOG PS 0, p = 0.04), and prior surgery (p = 0.03) were all independently associated with a higher probability of achieving a response.

Table 4.

Best tumor response by treatment group

| Response rate | Radiation | Radiation + cisplatin (20 mg/m2/wk) | Total | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 59 (37%) | 60 (40%) | 119 (39%) | 0.64 |

| PR | 48 (30%) | 57 (39%) | 105 (34%) | |

| CR + PR | 67% | 79% | 0.03 | |

| No change | 12 (8%) | 11 (7%) | 23 (7%) | |

| Progressive disease | 33 (21%) | 14 (9%) | 47 (15%) | |

| Unevaluable | 7 (4%) | 7 (5%) | 14 (5%) | |

| Total | 159 (100%) | 149 (100%) | 308 (100%) |

Abbreviations: CR = complete response; PR = partial response.

Table 5 summarizes the acute toxicities observed. The addition of weekly cisplatin significantly increased the frequency and severity of nausea/vomiting (p < 0.001) and of neurologic (p = 0.002), renal (p < 0.001), and hematologic toxicities (p < 0.001). Respiratory acute toxicities were increased in the RT + cisplatin group. The increased frequency of toxicities was primarily mild to moderate in severity. Toxicities within the radiation fields did not seem to be increased. Additional evaluation for laryngeal edema and nutritional toxicity was also evaluated with different grading schemas (Table 5). The addition of weekly cisplatin also did not significantly increase the spectrum and the severity of any of these toxicities. When each patient was classified by the worst grade of any type of toxicity, the treatment groups were comparable (p = 0.21).

Table 5.

Acute adverse effects

| Toxicity | Treatment | Grade

|

p value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Mod | Sev | LT | Lethal | |||||||

| Nausea/vomiting | RT | 84% | 7% | 8% | 1% | <0.001 | ||||||

| RT + P | 40% | 24% | 34% | 3% | ||||||||

| Diarrhea | RT | 94% | 3% | 3% | 0.45 | |||||||

| RT + P | 91% | 7% | 2% | |||||||||

| Infection | RT | 85% | 6% | 9% | 1% | 0.11 | ||||||

| RT + P | 79% | 5% | 13% | 3% | 1% | |||||||

| Hemorrhage | RT | 97% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0.80 | ||||||

| RT + P | 97% | 3% | ||||||||||

| Skin/mucosa | RT | 11% | 23% | 46% | 20% | 1% | 0.22 | |||||

| RT + P | 15% | 25% | 41% | 18% | 1% | |||||||

| Neurologic | RT | 94% | 3% | 4% | 0.002 | |||||||

| RT + P | 82% | 11% | 7% | 1% | ||||||||

| Respiratory | RT | 97% | 3% | 0.01 | ||||||||

| RT + P | 90% | 7% | 2% | 1% | ||||||||

| Genitourinary | RT | 87% | 11% | 1% | 1% | <0.001 | ||||||

| RT + P | 70% | 28% | 2% | 1% | ||||||||

| Hematologic | RT | 58% | 30% | 9% | 4% | <0.001 | ||||||

| RT + P | 29% | 37% | 23% | 10% | 1% | |||||||

| Renal | RT | 91% | 6% | 3% | 0.27 | |||||||

| RT + P | 87% | 9% | 3% | 1% | ||||||||

| Other | RT | 48% | 20% | 24% | 6% | 1% | 1% | 0.92 | ||||

| RT + P | 48% | 22% | 21% | 7% | 1% | |||||||

| Worst | RT | 4% | 10% | 53% | 31% | 1% | 1% | 0.21 | ||||

| RT + P | 2% | 11% | 47% | 36% | 3% | 1% | ||||||

| Laryngeal edema* | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||||

| RT | 65% | 18% | 14% | 3% | 0.72 | |||||||

| RT + P | 66% | 19% | 10% | 4% | 1% | |||||||

| Nutritional† | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| RT | 38% | 8% | 24% | 14% | 3% | 8% | 1% | 4% | 1% | 0.29 | ||

| RT + P | 34% | 7% | 21% | 21% | 1% | 8% | 2% | 3% | ||||

Abbreviations: Mod = moderate; Sev = severe; LT = lethal; RT = control arm treated with radiotherapy (RT); RT + P = experimental arm treated with radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin (P).

Laryngeal edema grading: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = moderate to severe with deterioration of voice, 4 = requires tracheostomy.

Nutritional acute toxicity grading: 0 = none, 1 = regular diet, 2 = soft diet, 3 = liquid diet, 4 = intravenous fluids, 5 = nasogastric tube, 6 = hyperalimentation, 7 = gastrostomy, 8 = hospitalization required.

Compliance was not measured other than a global evaluation for compliance to the treatment protocol on the Case Evaluation Form. The noncompliance was 16% (25/159) in the RT group compared to 32% (47/149) in the RT + cisplatin group. The number of cycles of cisplatin administered was not available.

Table 6 summarizes the late toxicities observed. Late toxicities were recorded on the Radiotherapy Long Term Follow-up Form. None of the late toxicities evaluated were significantly different except for two toxicities (p = 0.57). Both esophageal (9% vs. 3%, p = 0.03) and laryngeal (11% vs. 4%, p = 0.05) late toxicities were more prevalent in the RT + cisplatin group.

Table 6.

Late adverse effects

| Late effect | Radiation | Radiation + cisplatin (20 mg/m2/wk) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | 21% | 15% | 0.18 |

| Mucous membrane | 28% | 22% | 0.29 |

| Subcutaneous tissue | 11% | 13% | 0.60 |

| Esophagus | 3% | 9% | 0.03 |

| Larynx | 4% | 11% | 0.05 |

| Other | 13% | 16% | 0.52 |

DISCUSSION

The optimal dose for cisplatin radiosensitization is unclear, though a target cumulative dose of at least 200 mg/m2 is commonly advocated but is without much supportive evidence (15). Studies using the 100 mg/m2 × 3 regimen consistently show that about 70% of patients receive all three doses. Several reports have therefore questioned whether this high-dose bolus schedule is optimal (1, 13, 16). Hence, a fundamental but unanswered question is whether or not comparable cisplatin radiosensitization may be achieved with alternative schedules, such as weekly cisplatin, which may be better tolerated, improving compliance and achieving cumulative doses that approach 300 mg/m2 (15, 17–20).

The results reported here constitute part of the early efforts to determine whether cisplatin was an effective radiosensitizer and whether survival could be improved in a homogeneously defined unresectable study population with a poor prognosis. Comparable eligibility criteria were used to define the subsequent Intergroup Phase III trial E1392 (excluding nasopharyngeal carcinoma), which demonstrated superior disease-free survival and OS with the concurrent administration of 100 mg/m2 scheduled bolus cisplatin (13). Not only did E2382 permit nasopharyngeal carcinomas, but ECOG PS 2 and 3 patients compared to the now favored PS 0–1 for many clinical trials. These inclusion criteria account for the statistical significance of cell differentiation and PS seen in the univariate and multivariate analyses. Despite this, comparable results in the RT control arm in E1392 (13) and E2382 were observed (median survival: 12.6 months and 13.3 months, respectively) confirming the homogeneity and poor prognosis of the unresectable cohort.

Though they must be interpreted with caution, the superior survival results seen with concurrent cisplatin at 100 mg/m2 for three cycles in contrast to the marginal activity with 20 mg/m2 for seven weekly cycles (p = 0.09) are consistent with the notion that cisplatin radiosensitization may be more dependent on the total dose delivered than on the schedule. Effective tumor radiosensitization with weekly doses of cisplatin may likely necessitate doses greater than 20 mg/m2.

The evidence to support the use of higher weekly cisplatin doses is largely inferred. For definitive nonnasopharyngeal head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma, several small retrospective reports have described the results with weekly cisplatin at 30 mg/m2 (19) and 40 mg/m2 (15, 18, 20), suggesting that weekly cisplatin is active. Comparisons to every-3-week high-dose cisplatin have been reported because of changes in institutional practices, with comparable local-regional disease control rates observed at weekly doses of 33–40 mg/m2 (17) or 40 mg/m2 (18). Lower rates of nausea and vomiting and nephrotoxicity (18) and significantly higher cumulative doses were achieved with weekly cisplatin dosing, resulting in 65% of patients receiving ≥200 mg/m2 (18). However, lower cumulative doses with cisplatin dosed at 40 mg/m2/week have been reported (15). The use of weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2 as an effective radiosensitizer is also supported by level 1 evidence from clinical trials of endemic nasopharyngeal carcinoma (21, 22) and cervical carcinoma (23). Improved tolerance with higher rates of completed cycles and less dose reduction have been observed at weekly doses of 40 mg/m2 for nasopharyngeal (22) and cervical (23) carcinomas, with no evidence of increased late effects (23).

Although more effective tumor radiosensization likely requires weekly doses greater than 20 mg/m2, this dose was sufficient to significantly increase the risk of late laryngeal (11% vs. 4%) and esophageal (9% vs. 3%) toxicities. The low survival rates observed in this study may contribute to an underreporting of these late toxicities and suggest that this risk may be even higher. In as much as the current paradigm associates chronic oxidative stress with the development of radiation-induced fibroproliferative normal tissue injury (24), these observations suggest that even low weekly doses of cisplatin may be detrimentally contributing to non-selective oxidative injury of the normal tissues. Cisplatin not only induces DNA crosslink damage but can induce 8-OHdG moieties, reflecting its ability to increase oxidative stress to the cell with its cytotoxicity reduced by antioxidant therapy (25). Cancer cells have also been shown to have a greater antioxidant capacity in adaptation to the intrinsic oxidative stress of cancer progression (26).

Hence, weekly cisplatin at 20 mg/m2 may not offer the selective radiosensitization that was initially hoped for. It is unclear whether modern conformal radiation techniques, capable of limiting the radiation dose to threshold levels associated with injury to normal swallowing organs (27–29), may allow for more effective combination with higher weekly doses of cisplatin.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this Intergroup trial demonstrated that concurrent weekly cisplatin at a dose of 20 mg/m2 did not significantly improve upon the results seen with daily RT to 70 Gy. Although acute toxicities within the radiation field are not significantly increased, the risk of late swallowing toxicities is increased. Higher and potentially more effective weekly doses of cisplatin may pose similar risks and should be considered in future designs of clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (Robert L. Comis, M.D., Chair) and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA23318, CA66636, CA21115, CA32102, CA21661, CA37422, CA16116 and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

The authors thank George Adams, M.D., who served as the study Co-Chair, and John C. Marsh, M.D. who served as the Head and Neck Committee Chair during E2382.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- 1.Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri PG, et al. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: Phase III randomized Intergroup study 0099. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1310–1317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu KK, Pajak TF, Trotti A, et al. A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: First report of RTOG 9003. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pignon JP, le Maitre A, Maillard E, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): An update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourhis J, Overgaard J, Audry H, et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:843–854. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A, et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: An RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3582–3589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caudell JJ, Schaner PE, Meredith RF, et al. Factors associated with long-term dysphagia after definitive radiotherapy for locally advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langendijk JA, Doornaert P, Rietveld DH, et al. A predictive model for swallowing dysfunction after curative radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;90:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen LN, Ang KK. Radiotherapy for cancer of the head and neck: Altered fractionation regimens. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:693–701. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00906-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassen P, Eriksen JG, Hamilton-Dutoit S, et al. HPV-associated p16-expression and response to hypoxic modification of radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;94:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:92–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zelen M. The randomization and stratification of patients to clinical trials. J Chronic Dis. 1974;27:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinmann D, Cerny B, Karstens JH, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m(2) in 103 head-and-neck cancer patients: A cumulative dose-effect analysis. Strahlenther Onkol. 2009;185:682–688. doi: 10.1007/s00066-009-1989-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahl M, Siu LL, Pond GR, et al. Tolerability of the Intergroup 0099 (INT 0099) regimen in locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer with a focus on patients’ nutritional status. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:1127–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho KF, Swindell R, Brammer CV. Dose intensity comparison between weekly and 3-weekly Cisplatin delivered concurrently with radical radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: A retrospective comparison from New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton, UK. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:1513–1518. doi: 10.1080/02841860701846160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uygun K, Bilici A, Karagol H, et al. The comparison of weekly and three-weekly cisplatin chemotherapy concurrent with radiotherapy in patients with previously untreated inoperable non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:601–605. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traynor AM, Richards GM, Hartig GK, et al. Comprehensive IMRT plus weekly cisplatin for advanced head and neck cancer: The University of Wisconsin experience. Head Neck. 2010;32:599–606. doi: 10.1002/hed.21224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beckmann GK, Hoppe F, Pfreundner L, et al. Hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy in combination with weekly cisplatin for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2005;27:36–43. doi: 10.1002/hed.20111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan AT, Leung SF, Ngan RK, et al. Overall survival after concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:536–539. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Liu MZ, Liang SB, et al. Preliminary results of a prospective randomized trial comparing concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma in endemic regions of China. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1356–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stehman FB, Ali S, Keys HM, et al. Radiation therapy with or without weekly cisplatin for bulky stage 1B cervical carcinoma: Follow-up of a Gynecologic Oncology Group trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(503):e501–e506. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins ME, Zhao W. Chronic oxidative stress and radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: A review. Int J Radiat Biol. 2004;80:251–259. doi: 10.1080/09553000410001692726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston TJ, Henderson JT, McCallum GP, et al. Base excision repair of reactive oxygen species-initiated 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine inhibits the cytotoxicity of platinum anti-cancer drugs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2015–2026. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballatori N, Krance SM, Notenboom S, et al. Glutathione dys-regulation and the etiology and progression of human diseases. Biol Chem. 2009;390:191–214. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy of head and neck cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: Early dose-effect relationships for the swallowing structures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:1289–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levendag PC, Teguh DN, Voet P, et al. Dysphagia disorders in patients with cancer of the oropharynx are significantly affected by the radiation therapy dose to the superior and middle constrictor muscle: A dose-effect relationship. Radiother Oncol. 2007;85:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen K, Lambertsen K, Grau C. Late swallowing dysfunction and dysphagia after radiotherapy for pharynx cancer: Frequency, intensity and correlation with dose and volume parameters. Radiother Oncol. 2007;85:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]