Abstract

Loss of the lariat debranching enzyme Dbr1 is found to repress TDP-43 toxicity. The accumulated intronic lariat RNAs, which are normally degraded after splicing, likely act as decoys to sequester TDP-43 away from binding to and disrupting function of other RNAs.

A paradigm shift is underway in understanding mechanisms of several neurodegenerative diseases, with an increasing focus on errors of RNA metabolism and processing as a central underlying component. The discovery initiating this shift was that 43 kD TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) is a major component of ubiquitinated protein aggregates found in sporadic ALS and the most common form of frontotemporal dementia (disease with ubiquitinated inclusions or FTLD-U)1,2. Subsequently, mutations in TDP-43, and a related RNA binding protein FUS/TLS, have been found to be causative of both diseases. Moreover, TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions have been reported in both neurons and glial cells, not just in inherited and sporadic ALS and FTLD-U, but also in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's diseases3. The typical pathology of TDP-43 in patients includes nuclear clearance and cytoplasmic inclusions4. The disease mechanism(s) is still not clear, but probably involves both loss of normal function in the nucleus and/or gain of toxic properties from the cytosol aggregates.

Intense interest, therefore, has been brought to bear on the mechanism of TDP-43-induced pathogenesis as understanding it could potentially provide therapeutic opportunities for broad disease treatment. In this issue, by exploiting genome-wide loss-of-function screens in yeast to identify genes whose loss exacerbates toxicity, Armakola et al5 do just this, reporting discovery of an unexpected, potentially druggable modifier of TDP-43 cytotoxicity.

Screening modifiers of TDP-43 toxicity

While previously an overexpression screen to identify modifiers of TDP-43 aggregation and toxicity in yeast cells has been reported6, Armakola et al5 have now applied two genome-wide loss-of-function screens to identify new candidate genes that modify toxicity from high level expression of TDP-43 in yeast. They identify 6 enhancers and 8 suppressors in the first screen and an amazingly large number of potential enhancers and suppressors (2581 and 2056, respectively) in the second screen. They focus on one of the most effective deletion suppressors of TDP-43 toxicity – appearing in both screens - which is loss of the lariat debranching enzyme Dbr1, which cleaves the 2′-5′ phosphodiester linkage at the branch point of the circular lariats formed from processing introns out of a pre-mRNA. Action of Dbr1 converts lariats into linear RNAs that are subsequently degraded7,8 and this function is conserved from yeast to human. The outcome of the initial screen is extended with point mutants defective in debranching activity to show that it is Dbr1 activity that is required to suppress TDP-43 toxicity.

Recognizing the artificiality of an assay for toxicity of a high level of human TDP-43 in yeast, Armakola et al5 next test whether reduction in Dbr1 activity can mitigate TDP-43-dependent toxicity in two mammalian cell contexts. Initially, siRNA is used to transiently lower Dbr1 in a mitotically cycling, undifferentiated human neuroblastoma cell line in which doxycycline treatment induces accumulation of an ALS causing mutant TDP-43Q331K to a level comparable to what would be expected for a dominantly inherited mutant. By the end of the assay, mutant TDP-43 produced toxicity to a minority (20%) of cells (the effects of wild type TDP43 were not reported) and this toxicity was mostly alleviated by siRNA-mediated reduction in Dbr1. A more relevant test was then undertaken with primary cortical neurons transiently transfected to express TDP-43-EGFP and siRNA to Dbr1 or a control siRNA. Expression of wild type TDP-43 provoked toxicity over an 8 day period (the level of accumulated TDP-43 was not determined). Suppression of Dbr1 provided what the authors argue is a level of protection, albeit it must be acknowledged that many readers will probably find the protection too modest (50% versus 57% survivors in the presence or absence of Dbr1, respectively) to be fully persuasive.

Useful RNA “junk”

How can accumulation of intron-derived lariats be protective from TDP-43 toxicity? Broad effects of TDP-43 on mRNA levels and alternative splicing have been established following depletion of TDP-43 with both high-throughput sequencing and splicing-sensitive microarrays9,10. Many of the target genes encode proteins related to neuronal functions and/or implicated in neurological diseases. Genome-wide RNAs bound by TDP-43 in several cell or tissue systems have been identified9-12 and a consensus binding GU-rich binding motif has been identified9-13, with most of the TDP-43 binding sites lying deep within introns9-12. This makes it reasonable to hypothesize that lariat intron, the “junk” RNA normally degraded in wild-type cells but accumulated in dbr1Δ cells, serves as a decoy to sequester TDP-43 away from binding to and inhibiting function of normal RNAs that are trapped in the TDP-43 aggregates.

A combination of immunoprecipitation and electrophoretic mobility shift assays were used to provide evidence that TDP-43 directly binds onto lariat RNAs. To determine how and where the benefit of lariat accumulation occurs, lariats were visualized in living yeast using an RNA-binding MS2 coat protein tethering technique, coupled with immunocytochemistry. Lariat RNAs were found to co-localize with TDP-43 in bright foci in the cytoplasm of dbr1Δ yeast cells, a structure distinct from P-bodies or stress granules. This quite surprising result provokes many interesting questions: How does the lariat RNA get out of the nucleus to the cytoplasm? Is it the same in mammalian cells, especially in non-mitotically cycling differentiated neurons? Why could the relocalization of TDP-43 from one cytosol location (aggregates) to another (lariat foci) reduce its toxicity? Is the lariat structure or the sequence typically bound by TDP-43 within the intron (a GU domain) essential for the binding?

Furthermore, by comparing the dbr1Δ strain with three other yeast deletion strains that have defects in the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway, thereby resulting in aberrant accumulation of these non-functional RNAs that are normally targeted for rapid destruction, Armakola et al5 propose that rescue of TDP-43 toxicity is specific to intronic lariat RNA accumulation. However, it is also possible that the amount of RNA accumulated in these NMD mutant strains is not as high as after loss of Dbr1, and therefore toxicity is not alleviated because TDP-43 is not successfully competed off of normal cellular RNAs.

Clarification of the sequestration mechanism in mammalian cells is now essential for approaches based on diminishing Dbr1 activity to be developed into therapeutic strategies, for example, using drug inhibitors of its debranching activity. As an initial step, it will be important to establish if any other RNA binding proteins are sequestered onto lariat introns and away from their normal interaction partners, as this – obviously - could be harmful to the cells. This concern is especially important since splicing is rare for pre-mRNAs in budding yeast, while it is prominent in most mammalian pre-mRNAs. Additionally, it must now be determined whether TDP-43 sequestration to lariat decoys within the cytoplasm still promotes loss of its crucial nuclear function in nervous system9-12?

Whatever the case, Armakola et al's work5 contributes another piece to the puzzle of how dysfunction of RNA metabolism is involved in ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases. Future work to clarify the underlying pathogenic mechanisms will be characterization of additional candidate genes – beyond Dbr1 – that were identified in the genetic screens and whose loss of function either alleviates or exacerbates toxicity.

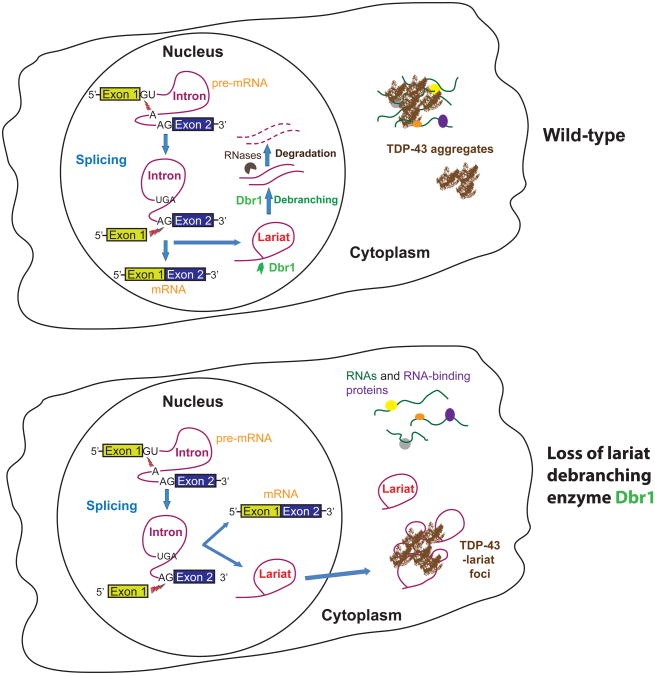

Figure 1.

Model for suppressing TDP-43 toxicity by loss of Dbr1. (a) Dbr1 normally converts intronic lariats into linear RNAs that are subsequently degraded by exonucleases. Cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregates sequester normal RNAs/RNA-binding proteins, thereby reducing their function. (b) Without Dbr1, lariats accumulate cytoplasmically, sequestering TDP-43 and diminishing its interference with normal RNAs.

References

- 1.Arai T, et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:602–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann M, et al. Science. 2006;314:130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagier-Tourenne C, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R46–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie IR, Rademakers R, Neumann M. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:995–1007. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armakola M, et al. Nature Genetics. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elden AC, et al. Nature. 2010;466:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature09320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arenas J, Hurwitz J. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4274–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman KB, Boeke JD. Cell. 1991;65:483–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90466-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polymenidou M, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:459–68. doi: 10.1038/nn.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tollervey JR, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:452–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sephton CF, et al. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1204–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao S, et al. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;47:167–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buratti E, Brindisi A, Pagani F, Baralle FE. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1322–5. doi: 10.1086/420978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]