Abstract

Objective

To determine clinical characteristics, demographics, and short-term outcomes of neonates diagnosed with fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH).

Design

We analyzed the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 1993-2008. Singleton births diagnosed with FMH were identified by ICD-9 code 762.3. Descriptive, univariate, and multivariable regression analyses were performed to determine the national annual incidence of FMH over time as well as demographics and clinical characteristics of neonates with FMH.

Results

Fetomaternal hemorrhage was identified in 12,116 singleton births. Newborns with FMH required high intensity of care: 26.3% received mechanical ventilation, 22.4% received blood product transfusion, and 27.8% underwent central line placement. Preterm birth (OR 3.7), placental abruption (OR 9.8) and umbilical cord anomaly (OR 11.4) were risk factors for FMH. Higher patient income was associated with increased likelihood of FMH diagnosis (OR 1.2), and whites were more likely to be diagnosed than ethnic minorities (OR 1.9). There was reduced frequency of diagnosis in the Southern United States (OR 0.8 versus the Northeastern United States).

Conclusions

Diagnosis of FMH is associated with significant morbidity as well as regional, socioeconomic, and racial disparity. Further study is needed to distinguish between diagnostic coding bias and true epidemiology of the disease. This is the first report of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in FMH, which may represent disparities in detection that require national attention.

Keywords: fetomaternal hemorrhage, neonatology, perinatal epidemiology, health care disparities, neonatal anemia

INTRODUCTION

Fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH) occurs when the normal flow of blood within the placenta is disrupted and fetal blood crosses into the maternal circulation. It is common for the placental filter to “leak” during normal pregnancies, resulting in transfer of small volumes of fetal whole blood into the maternal bloodstream. Volumes of fetal blood under 1 mL can be detected in up to 75% of pregnancies.(1) Large volume “severe” FMH causing adverse perinatal outcome is less common.(2) Estimates based on screening for RhD alloimmunization in RhD negative women suggest that severe FMH occurs in 1-3 in 1000 live births(3, 4) and accounts for almost 14% of otherwise unexplained fetal deaths.(5) Estimates of the incidence of severe FMH vary, primarily because no comprehensive epidemiologic studies of the condition have been conducted. Although established severe fetal anemia can be diagnosed in some cases by fetal heart rate monitoring or antenatal sonogram, the diagnosis of FMH is most commonly made after an adverse fetal or neonatal outcome has occurred, indicating the need for testing.(6) This raises the possibility of significant under-diagnosis of mild to moderate cases of the disease. Placental abruption, maternal hypertension, substance abuse, and maternal trauma have been suggested as clinical predictors of FMH, but have not been confirmed in comprehensive retrospective study of the disease in the general (RhD positive and negative) pregnant population.(7) Prospective evaluation of demographic or early clinical predictors of FMH has not been published. Estimates of the incidence of FMH significant to the fetus are drawn from small single-center or regional studies conducted twenty or more years ago, based on screening for Rh-immunization in pregnant RhD-negative woman.(1, 8) No recent evaluations of the incidence of FMH in the general pregnant population exist. Although a 1997 review article on FMH stated that the incidence of the condition was likely increasing,(6, 9) no published studies address trends in the incidence of FMH diagnosis over time. No published studies address racial and/or socioeconomic predisposition for the disease.

This study used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,(10) a database of nationally representative hospital discharge information, to trend the incidence of FMH diagnosis between 1993 and 2008. Additionally, we used discharge diagnosis codes to identify basic demographic characteristics as well as to determine associated diagnoses and health care resource utilization of neonates diagnosed with FMH during that period. We hypothesized that the incidence of FMH has increased in the United States over the past twenty years and that the incidence of FMH does not vary with socioeconomic class or race.

METHODS

We analyzed a multiyear data file concatenated from the 1993-2008 NIS. This database uses discharge data from 1054 hospitals in 42 states to present a statistically balanced representation of all hospitalizations in the United States in a given year based on 20% stratified sampling.

Hospital discharge diagnoses and procedures coded in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) were identified. Hospitalizations of interest were narrowed to the neonatal and peripartum hospitalizations using the HCUP codebook variable NEOMAT. Initial evaluation demonstrated virtually no maternal diagnosis coding for FMH (using the ICD-9 code 656.0). Due to this absence of maternal FMH diagnosis and the absence of any link between neonatal and maternal data in the NIS, maternal records were not included in analysis. Among the neonatal hospitalizations further analyzed in this study, patients diagnosed with FMH were identified via the ICD-9 code 762.3 (placental transfusion syndromes). ICD-9 codes have previously been validated for use in the neonatal population.(11-14) Multiple births were excluded from analysis based on the presence of any diagnosis code indicating twin or higher order multiple gestation (V310.0-1 V-, V312.0-1, V320.0-1, V321.0-1, V322.0-1, V330.0-1, V331.0-1, V332.0-1, V340.0-1, V341.0-1, V342.0-1, V350.0-1, V351.0-1, V352.0-1, V360.0-1, V361.0-1, V362.0-1, V370.0-1, V371.0-1, V372.0-1, V390.0-1, V391.0-1, V392.0-1, 651.0-9, 662.3, 761.5). This was necessary as diagnosis code 762.3 does not distinguish between FMH and twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Additional descriptive data, including patient characteristics (birth weight, race, gender, median income quartile for patient zip code, primary payer), hospital characteristics (region of country, rural versus urban location, teaching status; all as predefined in the NIS), as well as frequency of associated procedural and diagnostic codes were identified using the appropriate HCUP codebook variables. Specific diagnoses and procedures of interest were chosen based on investigator clinical experience. Procedure variables considered were mechanical ventilation, red blood cell transfusion (ICD-9 codes 967.1-2 and 990.4), central line placement (389.1 and 389.2), use of respiratory support (939.0, and 967.1), blood product transfusion (990.1, 990.4, and 990.5), and treatment for hyperbilirubinemia (990.1and 998.3). Diagnosis variables considered were neonatal seizure (779.0), hypotension (458.9), large for gestational age (766.1), hypovolemic shock (785.59), placental abruption (762.1), umbilical cord anomaly (762.6), birth asphyxia (768.5), disseminated intravascular coagulation (776.2), respiratory distress (769, 770.6, 770.7, 770.8, and 770.89), prematurity (762.3, 765.02, 765.03, 765.14, 765.15, 765.16, 765.17; 765.27, and 765.28), neonatal jaundice (774.2 and 774.6), neonatal anemia (776.5 and 776.6), abnormality of serum electrolytes (775.4, 775.5, 775.6, and 775.7), sepsis evaluation (V29.0, 771.8, and 771.81), and isoimmunization (773.1 and 773.2). As prematurity could conceivably either cause or result from FMH (due to early delivery for fetal distress), this variable was analyzed separately both as a predictor of FMH and as a clinical outcome of the disease.

National incidence of FMH was calculated annually using sample weights provided with the NIS. Weighting allows statistically appropriate extrapolation of raw percentages to national weights, based on the weighted sampling strategy of the NIS. To assess change in incidence of FMH over time, we performed univariate regression analysis with weighted frequency of FMH diagnosis as the dependent variable and calendar year as the independent variable. Additional univariate regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of FMH or outcomes of FMH respectively with 1) diagnosis of FMH as the dependent variable and diagnosis and procedure variables as the independent variable or 2) diagnosis or procedure variables as the dependent variable and diagnosis of FMH as the independent variable. Each diagnostic and procedure variable was evaluated for correlation with all others. Only significantly predictive, non-correlated variables (p<0.01, R<0.3) were included in multivariable analysis. To identify predictors of FMH, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed with FMH as the dependent variable and eligible procedure and diagnosis variable as independent variables. To identify outcomes of FMH, eligible procedure and diagnosis variables were serially introduced as dependent variables while including FMH and other non-correlated procedure and diagnosis variables as independent variables. In each of the regression models, patient demographic characteristics and hospital characteristics, were included as independent variables. Results of logistic regression models are reported as odds ratio (OR); 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 and SUDAAN 10.0.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., and Research Triangle Institute, both Cary, NC).

Because data were collected and de-identified before this study, the Program for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine deemed this project exempt from review.

RESULTS

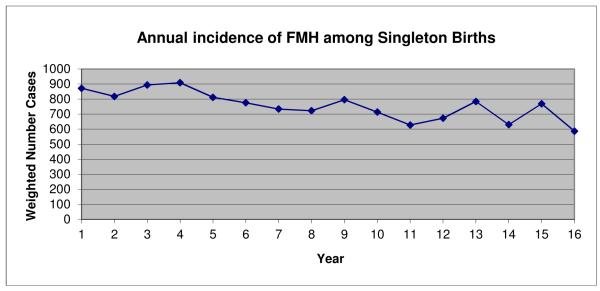

A weighted cohort of 65,516,569 singleton neonatal hospitalizations over 16 years was analyzed in this study. A diagnosis of FMH was identified in a weighted sample of 12,116 patients. The incidence of FMH diagnosis in the NIS fell 4.2% annually from a weighted incidence of 872 cases in 1993 to a weighted incidence of 587 cases in 2008 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence of FMH diagnosis over time among singleton births in the United States

In simple frequency analysis, there was no significant gender predilection for FMH. Significant predisposing factors for diagnosis of FMH included white race, preterm birth, placental abruption, and umbilical cord anomaly (Table 1A). Fetomaternal hemorrhage was more commonly diagnosed in patients with private insurance in higher income quartiles. Patients diagnosed with FMH were likely to be treated at urban teaching hospitals outside the Southern part of the United States (Table 1B). Patients with FMH required high intensity of care with 26.3% receiving mechanical ventilation, 22.4% receiving blood product transfusion, and 27.8% undergoing central line placement by frequency analysis (Table 1C).

Table 1.

A) Demographic and clinical predictors

| Diagnosis of FMH (n=12,116) | No diagnosis of FMH (n=65,437,646) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | Percent | Number of cases | Percent | ||

| Gender | Male | 6,166 ± 126 | 50.9 | 33,687,092 ± 9,305 | 51.5 |

| Female | 5,950 ± 125 | 49.1 | 31,750,554 ± 9,287 | 48.5 | |

| Race | White | 5,939 ± 119 | 56.0 | 27,198,560 ± 8,702 | 47.0 |

| Black | 1,020 ± 68 | 9.6 | 6,860,213 ± 5,703 | 11.9 | |

| Hispanic | 1,206 ± 72 | 11.4 | 10,032,815 ± 6,510 | 17.3 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 326 ± 39 | 3.1 | 2,004,453 ± 3,106 | 3.5 | |

| Native American | 115 ± 26 | 1.1 | 345,150 ± 1,331 | 0.6 | |

| Other | 381 ± 43 | 3.6 | 2,177,540 ± 3,246 | 3.8 | |

| Missing | 1,617 ± 82 | 15.2 | 9,234,754 ± 6,198 | 16.0 | |

|

Maturity

and Size |

Preterm birth | 3,681 ± 113 | 30.4 | 2,541,466 ± 3,496 | 3.9 |

| Large for gestational age | 416 ± 45 | 3.4 | 3,286,934 ± 3,999 | 5.0 | |

|

Uterine

Blood Flow |

Placental Abruption | 402 ± 44 | 3.3 | 54,872 ± 533 | 0.1 |

| Abnormal cord insertion | 386 ± 43 | 3.2 | 256,681 ± 1,142 | 0.4 | |

Table 1.

B) geographic an socioeconomic predictors

| Diagnosis of FMH (n=12,116) | No diagnosis of FMH (n=65,437,646) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | Percent | Number of cases | Percent | ||

| Payer | Medicare | 16 ± 9 | 0.1 | 110,057 ± 755 | 0.2 |

| Medicaid | 3,975 ± 118 | 32.9 | 25,036,105 ± 9,055 | 38.4 | |

| Private | 7,107 ± 122 | 58.9 | 34,811,761 ± 9,205 | 53.3 | |

| Self-pay | 573 ± 55 | 4.7 | 3,458,160 ± 4,118 | 5.3 | |

| No charge | 14 ± 8 | 0.1 | 107,855 ± 728 | 0.2 | |

| Other | 385 ± 43 | 3.2 | 1,755,764 ± 2,971 | 2.7 | |

|

Zip Code Income

Quartile |

0-25th percentile | 2,225 ± 97 | 20.0 | 13,918,713 ± 7,673 | 23.0 |

| 26th-50th percentile | 2,388 ± 98 | 21.4 | 13,916,051 ± 7,407 | 22.9 | |

| 51st to 75th percentile | 2,393 ± 98 | 21.5 | 13,344,827 ± 7,229 | 22.0 | |

| 76th to 100th percentile | 4,031 ± 114 | 36.2 | 19,004,110 ± 8,135 | 31.3 | |

| Other/Missing | 111 ± 23 | 1.0 | 456,525 ± 1,491 | 0.8 | |

|

Hospital

Location |

Rural | 1,733 ± 90 | 15.1 | 11,001,349 ± 7,145 | 68.7 |

| Urban | 9,773 ± 90 | 84.9 | 5,012,587 ± 7,002 | 31.3 | |

|

Teaching

Hospital |

Nonteaching | 5,098 ± 118 | 47.5 | 32,596,327 ± 8,701 | 56.9 |

| Teaching | 5,632 ± 120 | 52.5 | 24,735,488 ± 8,595 | 43.1 | |

|

Hospital

Region (U.S.) |

Northeast | 2,150 ± 96 | 20.0 | 9,955,799 ± 6,561 | 17.3 |

| Midwest | 2,621 ± 103 | 24.4 | 12,974,564 ± 7,277 | 22.6 | |

| South | 3,187 ± 105 | 29.6 | 20,357,175 ± 8,246 | 35.4 | |

| West | 2,795 ± 103 | 26.0 | 14,141,862 ± 7,402 | 24.6 | |

Table 1.

C) neonatal clinical outcomes associated with a diagnosis of FMH on univariate modeling

| Diagnosis of FMH (n=12,116) | No diagnosis of FMH (n=65,437,646) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | Percent | Number of cases | Percent | ||

| Cadiovascular | Hypotension | 555 ± 51 | 4.6 | 120,605 ± 773 | 0.2 |

| Shock | 365 ± 44 | 3.0 | 15,050 ± 278 | 0.0 | |

| Central line | 3,367 ± 112 | 27.8 | 1,082,743 ± 2,324 | 1.7 | |

| Pulmonary | Respiratory distress | 5,929 ± 125 | 48.9 | 5,336,305 ± 5,016 | 8.2 |

| Respiratory support | 3,142 ± 108 | 25.9 | 1,870,171 ± 3,030 | 2.9 | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3,184 ± 110 | 26.3 | 1,304,045 ± 2,544 | 2.0 | |

| Hematologic | Anemia | 3,708 ± 115 | 30.6 | 543,504 ± 1,647 | 0.8 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

254 ± 36 | 2.1 | 25,245 ± 358 | 0.0 | |

| Red blood cell transfusion | 2,502 ± 99 | 20.7 | 60,514 ± 29,4975 | 0.1 | |

| Any transfusion | 2,711 ± 102 | 22.4 | 339,057 ± 1,295 | 0.5 | |

| Jaundice | 3,816 ± 116 | 31.5 | 9,690,030 ± 6,472 | 14.8 | |

|

Treatment for

hyperbilirubinemia |

1,925 ± 90 | 15.9 | 2,368,013 ± 3,389 | 3.6 | |

| Any isoimmunization | 673 ± 56 | 5.6 | 1,245,712 ± 2,509 | 1.9 | |

| Neurologic | Asphyxia | 386 ± 43 | 3.2 | 256,681 ± 1,142 | 0.4 |

| Seizure | 633 ± 56 | 5.2 | 167,589 ± 923 | 0.3 | |

| FEN/GI | Electrolyte abnormality | 2,809 ± 104 | 23.2 | 1,793,289 ± 2,984 | 2.7 |

| ID | Evaluation for sepsis | 3,203 ± 109 | 26.4 | 5,155,607 ± 4,889 | 7.9 |

In multivariable logistic regression analysis the odds of FMH diagnosis was higher for Whites than Blacks (OR 1.89; CI 1.54, 2.27) or Hispanics (OR 1.85; CI 1.54, 2.22) (Table 2A). There was significantly decreased odds of FMH diagnosis with lower patient income (OR 0.85; CI) 0.74, 0.99) and location of birth in the Southern United States (OR 0.78; CI 0.62, 0.97) (Table 2B).

Table 2.

A) Demographic and clinical predictors

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Race (White referent) | 0.53 | 0.44-0.65 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic Race (White referent) | 0.54 | 0.45-0.65 | <0.0001 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander (White referent) |

0.70 | 0.53-0.94 | 0.0177 |

| Preterm birth | 3.67 | 2.90-4.64 | <0.0001 |

| Placental abruption | 9.77 | 7.18-13.31 | <0.0001 |

| Umbilical cord anomaly | 11.44 | 8.51-15.38 | <0.0001 |

Table 2.

B) geographic an socioeconomic predictors

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private Health Insurance | 1.29 | 1.14-1.47 | 0.0001 |

| 26th-50th percentile income quartile (76th-100th referent) |

0.85 | 0.74-0.99 | 0.0397 |

| Hospital located in the Southern U.S. (NE referent) |

0.78 | 0.62-0.97 | 0.0236 |

Prematurity (OR 3.67; CI 2.90, 4.64), placental abruption (OR 9.77; CI 7.18, 13.31) and umbilical cord anomaly (OR 11.44; CI 8.51, 15.38) were the strongest clinical predictors of FMH (Table 2A). Fetomaternal hemorrhage was a significant predictor of diagnosis of neonatal shock (OR 9.17; CI 5.89, 14.30), birth asphyxia (OR 8.76; CI 6.58, 11.67), disseminated intravascular coagulation (OR 2.41; CI 1.43, 4.08), abnormality of serum electrolytes (OR 2.79; CI 2.30, 3.38), neonatal seizure (OR 2.64; CI 1.98, 3.52), hypotension (OR 2.31; CI 1.68, 3.19), and prematurity (OR 3.22; CI 2.58, 4.02). It was also a significant predictor of procedures including central line placement (OR 3.94; CI 3.10, 5.02), use of respiratory support (OR 2.07; CI 1.66, 2.58), and blood product transfusion (OR 15.5; CI 12.41, 19.38) (Table 2C).

Table 2.

C) neonatal clinical outcomes associated with a diagnosis of FMH on multivariable modeling

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shock | 9.17 | 5.89-14.30 | <0.0001 |

| Asphyxia | 8.76 | 6.58-11.67 | <0.0001 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 2.41 | 1.43-4.08 | 0.001 |

| Abnormal electrolytes | 2.79 | 2.30-3.38 | <0.0001 |

| Seizure | 2.64 | 1.98-3.52 | <0.0001 |

| Hypotension | 2.31 | 1.68-3.19 | <0.0001 |

| Preterm birth | 3.22 | 2.58-4.02 | <0.0001 |

| Central line | 3.94 | 3.10-5.02 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory support | 2.07 | 1.66-2.58 | <0.0001 |

| Transfusion | 15.50 | 12.41-19.38 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment for hyperbilirubinemia | 0.89 | 0.71-1.11 | 0.3116 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study of incidence, predictors, and consequences of FMH in the general neonatal population in the United States. The major findings of this study are: 1) the incidence of FMH diagnosis among singleton live births has fallen significantly since 1993; 2) neonates diagnosed with FMH have significant associated morbidity; 3) neonates diagnosed with FMH have significant procedure-use; and 4) diagnosis of FMH is more common among Whites and those of higher socioeconomic status.

Fetomaternal hemorrhage is an understudied disease entity with significant associated morbidity. There are usually no outward signs of FMH-related severe anemia before stillbirth, fetal distress at delivery, or neonatal critical illness. Neonates that survive severe FMH have high rates of persistence of the fetal circulation, hypovolemic shock, and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy(6, 9) ultimately leading to mental retardation, cerebral palsy, neurologic devastation, and death.(15) Although FMH can be detected at the time of delivery by abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, demographic or early clinical predictors of severe FMH that could identify disease before adverse outcome occurs are unknown and no cause of hemorrhage can be identified in over 80% of cases.(9) Maternal or pregnancy risk factors appropriate for early screening or diagnosis of severe FMH in the general pregnant population have not been elucidated.(7, 16) If identified prior to delivery, fetal anemia from FMH may be successfully managed by intrauterine fetal transfusion and labor-free delivery.(17-19) Thus, identification of empirical predictors of FMH would offer immediate promise for improving clinical outcomes.

This study identified a significantly lower incidence of FMH among live births than was reported in previous, smaller studies of selected clinical populations.(2, 16) The only published incidence of FMH in the general pregnant population reports an incidence of FMH of 4.4% in miscarriages and stillbirths.(7) The incidence of FMH in the live born general population is unknown. No improvements in diagnosis of or care for FMH have come into widespread use since the introduction of pharmaceutical human RhD immune globulin in the 1960’s. For this reason, the discrepancy between the incidence of FMH seen in our study and those reported in older patient-oriented studies likely represents under-diagnosis of FMH. In fact, the incidence of FMH seen in the earlier years of patient cohort mimics the incidence of FMH found in a large population-based study of RhD incompatible pregnancies also reliant on clinical suspicion published in 1994.(2) We believe our analysis predominantly includes cases of severe FMH that prompt definitive testing, as supported by the high associated procedure use and morbidity of our patient cohort. Unfortunately, our data source does not define the method of diagnosis for FMH, so it is unknown whether cases of FMH identified in this study were diagnosed on clinical grounds or based on results of Kleihauer-Betke or flow cytometry testing.

This study also identifies a falling incidence of FMH over the years examined. Although there has been no significant advance in clinical testing for FMH over the years included in our study, significant advances in fetal evaluation have been made. Improvements in the quality and availability of fetal sonogram and antepartum testing may lead to delivery of fetuses in distress before the cause of that distress – sometimes FMH – becomes apparent. It may be that FMH as an entity is no less common today that it was twenty years ago, but that the adverse outcomes that lead to diagnosis of the disease are more commonly averted.

The demographic predictors of FMH diagnosis identified in this study may be important to clinical care. The significant socioeconomic, racial, and regional disparity in FMH diagnosis seen in our study are novel findings. Fetomaternal hemorrhage cannot be diagnosed without specific blood testing, commonly the Kleihauer-Betke acid elution test, that will not be performed without physician recognition of the possibility of FMH. We believe the significantly lower incidence of diagnosis in minority patients from lower socioeconomic quartiles represents under-diagnosis of FMH rather than a true lower incidence of disease in this population. This hypothesis should be evaluated in patient-oriented study with more detailed data source. If born out, this hypothesis indicates a significant need for obstetric and neonatal care provider education and a strong recommendation for FMH testing in all cases of congenital anemia.

A major strength of the approach taken in this study is the use of a nationally representative sample to examine ongoing questions about the changing incidence and general epidemiology of FMH diagnosis. No other published study examines a patient population with FMH as large as identified in the NIS. However, there are important limitations due to the quality of available data and the vagaries of diagnosis and medical practice. Discharge diagnosis codes are sometimes incomplete or inaccurate. Because of its exceedingly large size, the NIS should provide a statistically representative picture of health care use of neonates diagnosed with FMH on aggregate. Despite obvious limitations, discharge diagnosis codes have been previously validated for study of NICU outcomes and health care use.(11-14)

Additional limitations stem from the nature of the NIS. Maternal and neonatal data are not linked in the NIS, limiting validation of obstetric diagnoses such as abruption or umbilical cord abnormality. Additionally, the unit of record in the NIS is the hospitalization of interest, so it is not possible to correlate childhood diagnoses (such as cerebral palsy or mental retardation) with a neonatal diagnosis of FMH. We do not believe that these limitations affect our reported results, although they do prevent a more extensive analysis.

Finally, we are unable to ascertain whether regional discrepancies in diagnosis represent regional differences in disease incidence, recognition of the disease, or simply differences in regional coding practices.

In summary, fetomaternal hemorrhage, as identified in this large, nationally representative dataset, causes significant morbidity. Incidence of diagnosis has fallen since 1993, and is more common in Whites and those of higher socioeconomic status. Whether this overall decrease in incidence of diagnosis represents true decrease in incidence of disease or a rise in missed diagnoses requires further study. Prospective, patient-oriented study is needed to distinguish between diagnostic coding bias and true regional, racial, and socioeconomic patterns of occurrence of the disease. This is the first report of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in FMH, which may represent disparities in detection that require national attention.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH) occurs when the placental barrier fails and fetal blood crosses into the maternal circulation.

Although lifelong disability is common among children that survive FMH, early demographic or clinical predictors of FMH are unknown.

Although the incidence of FMH is suspected to be rising, a large longitudinal study of FMH to evaluate this claim has not been published.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This is the first study to identify the national incidence of FMH, clinical and demographic predictors of

FMH, and neonatal outcomes associated with FMH diagnoses.

This is the first report to suggest a falling incidence of FMH in a large population-based cohort.

This is also the first report to suggest regional, socioeconomic and ethnic/racial disparities in the diagnosis of FMH.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosures: Dr. Stroustrup and this study are supported by NIH KL2RR029885.

Abbreviations

- FMH

fetomaternal hemorrhage

- NIS

Nationwide Inpatient Sample

- HCUP

Health Care Cost and Utilization Project

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Neither author has a conflict of interest with this research.

Contributorship statement: The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. The sponsor, the National Institutes of Health, did not play any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation. Dr. Stroustrup wrote the first draft of the manuscript and no honorarium, grant, or other form of payment was given to anyone to produce this manuscript. Each author has seen and approved this manuscript prior to submission. Each author takes full responsibility for the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowman JM, Pollock JM, Penston LE. Fetomaternal transplacental hemorrhage during pregnancy and after delivery. Vox Sang. 1986;51:117–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1986.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Almeida V, Bowman JM. Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage: Manitoba experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology ACOG practice bulletin No 4: Prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;66:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wylie BJ, D’Alton ME. Fetomaternal hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. [Review] 2010 May;115(5):1039–51. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da7929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laube DW, Schauberger CW. Fetomaternal bleeding as a cause for “unexplained” fetal death. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:649–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubod C, Deruelle P, Le Goueff F, et al. Long-term prognosis for infants after massive fetomaternal hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:256–60. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000271212.66040.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samadi R, Greenspoon JS, Gviazda I, et al. Massive fetomaternal hemorrhage and fetal death: are they predictable? J Perinatol. 1999;19:227–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sebring ES, Polesky HF. Fetomaternal hemorrhage: incidence, risk factors, time of occurrence, and clinical effects. Transfusion. 1990;30:344–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30490273444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giacoia GP. Severe fetomaternal hemorrhage: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1997;52:372–80. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199706000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 1993-2008. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beeby PJ. How well do diagnosis-related groups perform in the case of extremely low birthweight neonates? J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:602–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford JB, Roberts CL, Algert CS, et al. Using hospital discharge data for determining neonatal morbidity and mortality: a validation study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:188. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krawczyk-Wyrwicka I, Piotrowski A, Rydlewska-Liszkowska I, et al. Calculating costs of premature infants’ intensive care in the United States of America, Canada and Australia. Przegl Epidemiol. 2005;59:781–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroustrup A, Trasande L. Epidemiological characteristics and resource use in neonates with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: 1993-2006. Pediatrics. 2010;126:291–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kecskes Z. Large fetomaternal hemorrhage: clinical presentation and outcome. J Matern Fetal Neona. 2003;13:128–32. doi: 10.1080/jmf.13.2.128.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David M, Smidt J, Chen FC, et al. Risk factors for fetal-to-maternal transfusion in Rh D-negative women--results of a prospective study on 942 pregnant women. J Perinat Med. 2004;32:254–7. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2004.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennand J, Cameron A. Fetal anaemia: diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer RL, Kuhlman K, Grover J, et al. Chronic, massive fetomaternal hemorrhage treated with repeated fetal intravascular transfusions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:203–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubod C, Houfflin V, Belot F, et al. Successful in utero treatment of chronic and massive fetomaternal hemorrhage with fetal hydrops. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2006;21:410–3. doi: 10.1159/000093881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]