Abstract

Objective

The slow adoption of electronic health record (EHR) systems has been linked to physician resistance to change and the expense of EHR adoption. This qualitative study was conducted to evaluate benefits, and clarify limitations of two mature, robust, comprehensive EHR Systems by tech-savvy physicians where resistance and expense are not at issue.

Methods

Two EHR systems were examined – the paperless VistA / Computerized Patient Record System used at the Veterans’ Administration, and the General Electric Centricity Enterprise system used at an academic medical center. A series of interviews was conducted with 20 EHR-savvy multiinstitutional internal medicine (IM) faculty and house staff. Grounded theory was used to analyze the transcribed data and build themes. The relevance and importance of themes were constructed by examining their frequency, convergence, and intensity.

Results

Despite eliminating resistance to both adoption and technology as drivers of acceptance, these two robust EHR’s are still viewed as having an adverse impact on two aspects of patient care, physician workflow and team communication. Both EHR’s had perceived strengths but also significant limitations and neither were able to satisfactorily address all of the physicians’ needs.

Conclusion

Difficulties related to physician acceptance reflect real concerns about EHR impact on patient care. Physicians are optimistic about the future benefits of EHR systems, but are frustrated with the non-intuitive interfaces and cumbersome data searches of existing EHRs.

Keywords: Adoption, electronic health record

Introduction

President Obama and former President Bush have called for the complete implementation of electronic health record systems across the United States by 2020 [1, 2]. National organizations including the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Hospital Organizations and the Leapfrog Group, along with federal agencies such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, have advocated for the early adoption of health information technology as a way to improve patient care. The EHR is viewed as the solution to many challenges that exist in our health care system. It is promoted for its promise to improve health care quality, prevent unnecessary variations in care, and reduce medical errors [3–7].

Despite this, adoption of health information technology has moved slowly since the introduction of technology to the international healthcare industry in the 1980’s. In the United States, adoption rates range from 12–24%, dependent on size of practice [8, 9]. Physician resistance to technology is often cited as a cause [8, 10–12]. Reasons for this resistance include lack of time for documentation, lack of knowledge about the system, privacy concerns, lack of standardization between systems, and the costs to deploy a technology solution [13–15].

In our previous study of academic and private physicians, we learned that resistance from both physician groups was related to the perceived impact of technology on communication, workflow, and patient care [16]. The selection of a broad sample of physician leaders and decision makers included a segment of older and less technically savvy users, who may not represent the segment of physicians most likely to adopt, use and improve EHR systems.

The objective of this research is to explore the perceptions of technically-savvy physicians of the impact of an EHR on patient care, where knowledge and adoption were not barriers to EHR use. More specifically, the aims are

-

1.

to document EHR interactions that impact acceptance,

-

2.

to describe functionality areas that affect patient care, and

-

3.

to compare the characteristics of the two EHR systems studied.

The physicians in the study practice at two institutions with long-standing comprehensive EHR’s, the Veteran’s Administration Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System (VAHC), and The Nebraska Medical Center (TNMC).

In this qualitative study, we examine whether a gap exists between physician super-users who are well versed in EHR use and health information technology, and our original study sample. Super-users are technically adept users who are trained to provide support to other users and serve as product champions, leading the way in their organization for technology change [17]. Super-users may play a significant role in successful technology adoption by providing insight into daily tasks and workflow, and providing support to other users during system implementation [18–20]. We explore the perceptions and insights from physician super-users who practice at TNMC as well as the VAHC in Omaha. This research extends the previous study by seeking to eliminate a potential bias against EHR use by practitioners who are technology neophytes and are resistant to change. Our sample includes recognized super-users of the EHR who have practiced only in facilities with an established comprehensive EHR.

Methods

The research objective was to understand the use of health information technology by technically adept physicians, and to compare their experiences with two well-known and comprehensive EHR systems. A qualitative design was chosen to allow meaningful insight into the potential variables and social interactions that impact the acceptance of EHR systems. Grounded theory guides both the collection and analysis of data to identify underlying concepts which describe the experience of a social group and the meanings associated with a phenomenon of study [21–23]. The qualitative method used in this study facilitates an understanding of physicians’ adoption of technology by exploring their perceptions of EHR system interaction. This approach allows for collection of a rich contextual narrative to provide meaningful insight into the user’s experiences, beliefs and values, and how these factors influence adoption.

The Veterans Administration has been a leader in the development and adoption of a robust EHR, and has received attention for its well-developed and comprehensive EHR system beginning with the development of VistA in the mid 1980’s [24, 25]. The system was later enhanced with the introduction of a user interface, the Computerized Patient Records System (CPRS). This comprehensive EHR contains components that include inpatient and outpatient documentation, Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE), alerts, medications, problem lists, image storage and retrieval, communications/routing, e-signature, progress note storage and templated notes.

TNMC is a not for profit hospital system that includes both academic and private physicians. TNMC has used GE Centricity Enterprise and its predecessors (IDX and Phamis), a commercially available comprehensive EHR, for inpatient and outpatient care for over 20 years [26]. As implemented, it has limited CPOE functionality and note templates, utilizes interfaces for external image storage and retrieval, and contains progress notes in both electronic and PDF formats.

Participants

The Chair of the Department of Medicine and Chief of General Medicine, who has published extensively on the subject of the EHR, identified a convenience sample of super-users from a comprehensive list of faculty, residents and fellows who practice at both institutions. Small group sessions were performed with a total of 20 participants, including 9 residents and 11 faculty members who accepted our invitation. The initial analysis of the first 18 participants did not yield saturation, and sessions were conducted with two additional faculty members chosen from the convenience sample. As a group the participants were sophisticated users of the EHR. They were familiar and comfortable with each medical record system, and in some cases, worked with information technology members to develop templates and forms used by the systems, advised EHR vendors on functionality, and published articles on health information technology. Additionally, several of the faculty members were experienced with other EHR systems, including Epic and Cerner.

Data Collection

Focus groups were conducted with physicians who practice at both institutions. Participants were asked open-ended questions about their interaction with EHR systems and the systems perceived benefits and limitations. The EHR systems selected for the study have been maintained and used consistently, for over 20 years at their respective institutions. Focus group sessions and analysis took place from November 2008 through December 2009. An average of 5 participants attended sessions for approximately one hour. Proceedings were digitally recorded and then transcribed. Theoretical sampling was used to identify users for additional focus group sessions as part of the concurrent data analysis until no new concepts were discovered, and saturation was achieved [21]. The resulting transcripts were reviewed for completeness and clarity prior to data analysis.

Data Analysis

Using the data analysis method of constant comparison, the two investigators independently reviewed the transcripts [23]. Concepts were found using an iterative process of reviewing transcripts following each session, identifying patterns within the participants’ responses, and annotating the transcripts. NVivo v8.0 software was used to formalize the concepts and facilitate the bottom-up formulation of themes. The relevance and importance of themes was assessed using a schema of frequency, convergence and intensity. Frequency represents the number of times that the topic appears in the users’ discussion, and was documented using NVivo’s frequency reporting feature. Convergence, the relative occurrence of the topic across both EHR systems, was assessed by each reviewer as high, medium, or low. Intensity was defined as the emotion and importance of the topic to the speaker, using a scale of high, medium or low based on a subjective analysis of the digital recording for vocal tone, pace and volume. An example of a high intensity statement by a participant is “you actually have more interaction with the damn computer than the patient.” The reviewers also noted whether the participants’ perceptions were positive or negative toward the respective EHR system. The emergent themes and the rating schema were examined in an open dialogue among investigators until consensus was achieved.

Trustworthiness and credibility of the study findings were demonstrated with the following methods [27]. The investigators (an informatics researcher/practicing physician at a teaching hospital, and a researcher experienced in information technology design) independently reviewed the transcripts, and then met periodically to review their emerging themes. A third investigator (a public health researcher with qualitative study expertise) audited the identification of concepts and the formulation of themes process to ensure consistency during the collection and analysis of the data. Through an iterative process of comparative analysis [28], reviewers achieved consensus on important themes, and potential biases in interpretation were reconciled.

Results

Patient care was at the center of many of the discussions, and serves as a framework for the successes and weaknesses of the EHR. ►Table 1 describes the resulting themes and their relative importance to the participants, and summarizes the benefits and limitations of each EHR. Two themes emerged to describe EHR interactions that relate to patient-specific data at the point-of-care; the relationship of the EHR to physician workflow and the EHR’s association with communication issues. Two additional themes described EHR interactions that were associated with aggregated EHR patient data-education, and outcomes/research. These are described in more detail below.

Table 1.

Impact of TNMC and VAHC electronic health record systems

| Theme | TNMC | VAHC |

|---|---|---|

|

Workflow (Frequency = 55%, Convergence – High, Intensity – High) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Communication (Frequency = 15%, Convergence – High, Intensity – High) |

|

|

| + Supports interaction with nursing | – Difficult searches for specific patient data | |

|

Outcomes / Research (Frequency = 11%, Convergence – Low, Intensity – Low) |

|

|

|

Education (Frequency = 4%, Convergence – Low Intensity – Low) |

|

|

Physician Workflow – Direct Influence on Patient Care

Physician workflow, as defined by the participants, is the complex physical interaction of the physician with information and with patients, which includes the amount of time needed to capture, retrieve and process information using the EHR. This theme was frequently noted for both EHR systems. Physicians spoke about the benefits of workflow, and strongly valued the accessibility of patient data when it was needed at the point-of-care, which was present in both TNMC and VAHC EHR systems. Participants also spoke strongly about the negative impact of both EHRs on physician workflow, and reinforced their concerns about the expanded overhead for documentation. A common perception was that the high cost of input and retrieval of an individual patient’s information significantly reduced time available for direct patient care.

Differences were noted between the two EHR systems on issues of usability. The TNMC system was better organized but less comprehensive, with the need to access scanned documents. Participants using the TNMC EHR system spoke about the difficulties of completing documentation during a patient visit:

“So, we don’t type in our clinic notes at this point. But we spend a lot of time outside of clinic documenting.”

“I just finished clinic and I now have 12 charts to dictate sometime today.”

VAHC users found the system was more comprehensive but very difficult to search. Use of templated notes at the VAHC saved documentation time and improved documentation compliance but at the expense of readability and comprehension. Participants echoed concern about documentation, and spoke directly about an interface that supported both data entry and retrieval:

“Follow up involving order entry takes at least 5–10 minutes per patient, so if you add that on to the end of your day – it is at least an extra hour, because nothing goes on paper, and it’s not convenient to enter info until you’re finished with seeing all patients.”

“I want it to be intuitive ... I don’t want to have to ask somebody to make it for me.”

“You have chaplain notes, you have PT notes, you have everything and literally you’re looking at a list that for one patient’s hospitalization may be a list of 300 notes.”

Communication – Direct Influence on Patient Care

Communication is the interaction between physician and patient, as well as communication within the healthcare team. Like workflow, the theme of communication was common across EHR systems, and evoked intense responses from participants. Physicians recognized benefits that included improved communication, the availability of patient data asynchronously, and the ability to share patient-centric information with other physicians, and with patients. However, direct communication between health care providers was a frequent complaint, distancing consultants from primary care providers and physicians from nurses in the inpatient environment. This was perceived as a substantially greater problem at the VAHC than TNMC. In the outpatient environment the availability of reports from other providers was viewed as a positive, however, searching through the records was still perceived as more difficult at the VA.

“[at TNMC there is] lots of interaction with nurses, they get to know who you are and often provide additional information about your patient – that happens just because of physical presence – it provides another opportunity to share relevant information that doesn’t happen at the VA because there is less interaction. This collaboration also provides more reliability that orders are followed.”

“I don’t think that you can rely on the medical record system to provide you all the communication that you need because any electronic system still needs to be overridden by human initiation in terms of a phone call or a page.”

Outcomes/Research and Education – Indirect Influence on Patient Care

Outcomes/research is a theme that describes the use of data in a structured and summarized way to satisfy research, outcomes and billing, and includes the capture of data in the appropriate formats. Education describes the use of technology to support the physician’s medical education, as well as any learning that is required to effectively use the EHR system.

Although less common, physicians perceived potential EHR benefits to improve patient outcomes and support research for populations. Yet, at the individual patient level, both systems were viewed as cumbersome and “not very helpful”. In addition, the responses related to education were also mixed, but tended to be more positive. Both faculty and residents were positive about the impact of web-based educational content such as UpToDate and Google scholar. Both groups also expressed concern about the difficulty in learning how to use EHR systems.

“The longer you are at the VA, the more tricks you learn about using it and it becomes more and more powerful but sometimes that learning curve is very steep.”

Summary of Themes

The comprehensive EHR systems studied had perceived strengths but also important limitations. Both TNMC’s GE Centricity Enterprise System and the VAHC’s CPRS system were praised for presenting patient data when it was needed at the point-of-care, addressing workflow issues of integrated access to patient data, clinical guidelines, and evidence-based domain knowledge within the space of a patient visit. The systems also were acknowledged for the potential to improve communication through the sharing of patient data among the diverse members of the healthcare team through direct access or a reporting interface. Physicians using both systems concurred on the unrealized potential for the EHR to positively impact on population health as well as to contribute to ongoing physician education through the potential delivery of evidence-based knowledge at the bedside.

While participants would not return to paper-based systems, the positive benefits of the EHR were offset by its limitations. These concerns included disruptions to patient management workflow needed to complete required documentation, elimination of face-to-face communication and feedback, as well as the potential for cumbersome data gathering for research and the potentially high learning curves for increasingly sophisticated EHR systems. Individually, the TNMC system was noted for its logical organization, but it was limited by difficult searches for patient information due to the inclusion of structured and non-structured documents. The VAHC system was applauded for its comprehensive nature, but it was considered non-intuitive and labor intensive. Neither system adequately addressed physician needs related to workflow, communication, outcomes/research, and education.

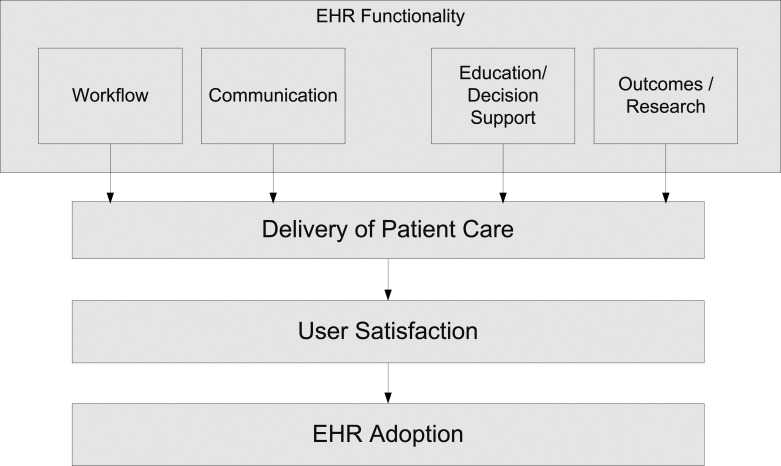

The adoption of EHR systems is influenced by how well system functionality supports the relationship between the physician and patient. The model described in ►Figure 1 is grounded in the findings from the study, and depicts a patient-centric rather than top-down approach to EHR adoption and usage, and defines relationships that can serve as a framework for future study. The model provides a structure to describe the relationship between desired EHR features and the satisfaction of the physician with EHR system use, which is moderated by physician commitment to the stability and improvement of patient care. The resulting framework provides an opportunity to explore each feature category. For instance, an improved workflow design, accomplished through addressing the issues of ease of documentation and the ability to share real-time patient information may improve the physicians’ perception of delivery of care. The resulting user satisfaction can then be examined for its relationship to EHR adoption.

Fig. 1.

Drivers for EHR system adoption and usage

Discussion

Our study documents the gap that is present between leaders who call for the rapid implementation of health information technology and physicians (even the tech savvy) who are practicing in the trenches. Present solutions for EHR adoption emphasize financial incentives, rather than address functionality areas such as physician workflow and communication, which can improve patient care [29]. The physicians interviewed were committed to the potential of the EHR and were positive about its potential usefulness. However, their acceptance was tempered by their frustration with ease of use – particularly the impact of trade-offs between patient care and the significant time required to search for information and input data.

Our previous study, as part of an Integrated Advanced Information Management Systems (IAIMS) project, explored issues related to the broad acceptance of EHRs by health care professionals and administrators. Although the physicians in the study believed that the EHR is inevitable, surprising to us was the strong concordance of concerns raised by both private and academic practitioners about the perceived negative impact of the institution’s EHR on patient care. In contrast, administrators believe that creation of administrative data is the primary job of the EHR, and eagerly anticipate the availability of the data for quality and outcome measurements. A concern of the study was that it did not include a sufficient number of young physicians in the sample, and that it examined a single EHR.

Both studies reflect similar perceptions from the participating physicians – whether they were general EHR users, or EHR super-users, particularly regarding workflow. Physicians felt that EHR applications were not designed to support their workflow, and often interrupted their interaction with patients. Although not part of our study, additional information surfaced to support the assertion that EHR use impacts negatively on direct patient care. We learned that VAHC internal medicine clinics have reduced the number of available time slots from 8 patients to 6 patients in a 4 hour clinic to compensate for the additional time spent at the computer. In addition, an internal study of workflow at TNMC indicated that house staff spent an average of 24 minutes for each inpatient. This included 20 minutes for preparation and follow-up, and only 4 minutes of direct patient care [30].

Overcoming adoption barriers requires strategies which span organizational and domain boundaries and identify categories of issues which include design, management, organization, and assessment. Successful adoption requires an understanding of EHR users and their work setting [31–34]. Clinical workflows are often complex, and effort is underway to better understand users and their tasks within the context of the clinical setting [35]. Many clinical systems have been commercially developed, yet research confirms issues with communication and workflow [36–39]. A critical piece often missing from EHR implementations is the input of the doctors, nurses and pharmacists who can identify what is needed to improve their jobs [40]. This lack of participation leads to challenges that are often found in EHR implementations in the US, and reinforces the need to enlist physicians in usability analysis and system design.

The experienced EHR users in this study call into question assumptions and strategies currently touted by US government leaders who call for the rapid implementation of technology [41]. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology propose that aggressive healthcare quality and efficiency improvements be driven top-down by national initiatives. Financial incentives to encourage EHR use beginning in 2010 have been prescribed, while at the same time, policies and standards for EHR design are being formulated [42, 43].

Limitations

Our findings, define relationships between themes, but do not verify causality. The rich description expands what is known about physician needs, and creates opportunity for ongoing research on antecedents for EHR usage.

Both faculty and residents were consistent in their perceptions of EHR impact on workflow, communication, and outcomes/research, therefore we did not separate the participants into groups based on years of experience. The groups differed slightly on the minor theme of education. Faculty expressed some concern about dilution of the medical education experience, yet both groups agreed on the potential benefits of the use of the EHR during medical training.

Recommendations

This study suggests EHR adoption will be stimulated by an approach which addresses user satisfaction by focusing on a patient-centric, rather than transactional, view of patient data. This includes the involvement of users in the identification of requirements that improve the effectiveness of workflow and communication, testing the usefulness and usability of interfaces, as well as the pursuit of collaborative design methodologies that combine the expertise of computer scientists, informaticists and clinicians. Current top-down efforts to spur EHR adoption, such as the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH), focus on financial compensation for clinicians and hospitals. This approach overlooks both documented issues with system usability and the needs of its most sophisticated users, which may limit its success in improving EHR adoption.

Conclusion

Contrary to many observers outside the practicing community, the issues related to physician acceptance of an EHR system are not due to reluctance to adopt new technology but on real concerns about the adverse impact of EHRs on the delivery of patient care. Physicians are optimistic about EHR potential for systematic collection of data to improve patient care, but are frustrated with the cumbersome interfaces and processes of existing EHR systems.

A significantly greater effort in EHR development needs to be made to meet the needs of end-users. EHR vendors (including the VAHC) need to work with health care providers to facilitate workflow and health care team communications, and to better understand the impact of technology on patient care. The potential for EHRs to positively transform healthcare is real but not yet fully realized in current systems. Effective use of an EHR system will require more than top-down policies and incentives. It will require the input of physicians who best understand the impact of technology on patient care. Much work is yet to be done.

“...on the whole, both systems are better than the paper systems we had years ago.”

Clinical Relevance Statement

Our study suggests that low EHR acceptance by tech-savvy physicians is related to insufficient functionality and its potential negative impact on patient care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in the research.

Human Subjects Protections

The study was performed in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, and was reviewed by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained in all cases.

References

- 1.The White House – Press Office – Remarks of President Barack Obama – Address to Joint Session of Congress [Internet]. Washington: The White House; [updated 2009 Feb 24; cited 2011 Jul 11]. Available fromhttp://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-of-President-Barack-Obama-Address-to-Joint-Session-of-Congress/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Executive Order 13410: Promoting Quality and Efficient Health Care in Federal Government Administered or Sponsored Health Care Programs [Internet]. Washington: Federal Register; [updated 2006 Aug 26; cited 2011 Jul 11]. Available fromhttp://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2006/pdf/06–7220.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koshy R.Navigating the information technology highway: computer solutions to reduce errors and enhance patient safety. Transfusion 2005; 45(4 Suppl): 189S-205S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safety,Committee on Data Standards for Patient Patient Safety: Achieving a new standard for care. 1st ed.: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academy of Sciences Key capabilities of an electronic health record. 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates DW, Cohen M, Leape LL, Overhage JM, Shabot MM, Sheridan T.Reducing the frequency of errors in medicine using information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2001; 8(4): 299–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America To err is human: Building a safer health system. 1st ed.: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford EW, Menachemi N, Peterson LT, Huerta TR. Resistance is futile: but it is slowing the pace of EHR adoption nonetheless. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009; 16(3): 274–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdolrasulnia M, Menachemi N, Shewchuk RM, Ginter PM, Duncan WJ, Brooks RG. Market effects on electronic health record adoption by physicians. Health Care Manage Rev 2008; 33(3): 243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balfour DC, 3rd, Evans S, Januska J, Lee HY, Lewis SJ, Nolan SR, et al. Health information technology – results from a roundtable discussion. J Manag Care Pharm 2009; 15(1 Suppl A): 10–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford EW, Menachemi N, Phillips MT. Predicting the adoption of electronic health records by physicians: when will health care be paperless? J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006; 13(1): 106–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geibert RC. Using diffusion of innovation concepts to enhance implementation of an electronic health record to support evidence-based practice. Nurs Adm Q 2006; 30(3): 203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poissant L, Pereira J, Tamblyn R, Kawasumi Y.The impact of electronic health records on time efficiency of physicians and nurses: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2005; 12(5): 505–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates DW. Physicians and ambulatory electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005; 24(5): 1180–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menachemi N, Ford EW, Beitsch LM, Brooks RG. Incomplete EHR adoption: late uptake of patient safety and cost control functions. Am J Med Qual 2007; 22(5): 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabenbauer L, Fraser RS, McClay JC, Woelfl N, Thompson CB, Campbell J, et al. Adoption of electronic health records: A qualitative study of academic and private physicians and health administrators. Appl Clin Inf 2011; 2: 165–176 http://dx.doi.org/10.4338/ACI-2011–01-RA-0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitten J, Bentley L.Systems Analysis and Design Methods 7th ed: McGraw-Hill/Irwin <SKU>; 913464-A10–0073052337; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenzi NM, Kouroubali A, Detmer DE, Bloomrosen M.How to successfully select and implement electronic health records (EHR) in small ambulatory practice settings. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 200923; 9: 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halbesleben JR, Wakefield DS, Ward MM, Brokel J, Crandall D.The relationship between super users' attitudes and employee experiences with clinical information systems. Med Care Res Rev 2009; 66(1): 82–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbin J, Strauss A.Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed.: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research :grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. editors. The discovery of grounded theory : strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co.; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scalzi T.The VA leads the way in electronic innovations. Nursing 2007; 37(9): 26–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovis C, Payne TH. Extending the VA CPRS electronic patient record order entry system using natural language processing techniques. Proc AMIA Symp 2000: 517–521 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centricity Enterprise – Healthcare IT Solutions General Electric Healthcare; [updated 2011 Jul 11; cited 2011 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www2.gehealthcare.com/portal/site/usen/menuitem.e8b305b80b84c1b4d6354a1074c84130/?vgnex-toid=5b83e73922f30210VgnVCM10000024dd1403RCRD&vgnextfmt=default&productid=4b83e73922f30210VgnVCM10000024dd1403____

- 27.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1st ed.: Sage Publications, Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miles MB, Huberman M.Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook 2nd ed.: Sage Publications, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumenthal D.Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med 2009; 360(15): 1477–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UNMC Internal Documentation Physician Workflow. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorenzi NM, Novak LL, Weiss JB, Gadd CS, Unertl KM. Crossing the implementation chasm: a proposal for bold action. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2008; 15(3): 290–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorenzi NM. Strategies for creating successful local health information infrastructure Initiatives. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorenzi NM, Riley RT. Managing change: an overview. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2000; 7(2): 116–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorenzi NM, Riley RT. Organizational issues = change. Int J Med Inform 2003; 69(2–3): 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malhotra S, Jordan D, Shortliffe E, Patel VL. Workflow modeling in critical care: piecing together your own puzzle. J Biomed Inform 2007; 40(2): 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGrath JM, Arar NH, Pugh JA. The influence of electronic medical record usage on nonverbal communication in the medical interview. Health Informatics J 2007; 13(2): 105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra RH. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007; 14(4): 415–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, Frankel RM. Lost in translation: challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med 2005; 80(12): 1094–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weir CR, Nebeker JR. Critical issues in an electronic documentation system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2007: 786–790 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Javitt JC. How to succeed in health information technology. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004; SupplWeb Exclusives:W4–321–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.State of the Union [Internet] Washington: The White House; [updated 2010 Jan 27; cited 2011 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-state-union-address [Google Scholar]

- 42.Report to the President Realizing the Full Potential of Health Information Technology to Improve Healthcare for Americans : The Path Forward [Internet]. Washington: President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology; [updated 2010 Dec 8; cited 2011 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/pcast-health-it-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blumenthal D, Tavenner M.The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(6): 501–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]