Abstract

STUDY DESIGN

Randomized clinical trial.

OBJECTIVES

Determine effective interventions for improving readiness to return to sports post-operatively in patients with complete, unilateral, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture who do not compensate well after the injury (noncopers). Specifically, we compared the effects of 2 preoperative interventions on quadriceps strength and functional outcomes.

BACKGROUND

The percentage of athletes who return to sports after ACL reconstruction varies considerably, possibly due to differential responses after acute ACL rupture and different management. Prognostic data for noncopers following ACL reconstruction is absent in the literature.

METHODS

Forty noncopers were randomly assigned to receive either progressive quadriceps strength-training exercises (STR group) or perturbation training in conjunction with strength-training exercises (PERT group) for 10 preoperative rehabilitation sessions. Postoperative rehabilitation was similar between groups. Data on quadriceps strength indices [(involved limb/uninvolved limb force) ×100], 4 hop score indices, and 2 self-report questionnaires were collected preoperatively and 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare functional differences between the groups. Chi-square tests were used to compare frequencies of passing functional criteria and reasons for differences in performance between groups postoperatively.

RESULTS

Functional outcomes were not different between groups, except a greater number of patients in the PERT group achieved global rating scores (current knee function expressed as a percentage of overall knee function prior to injury) necessary to pass return-to-sports criteria 6 and 12 months after surgery. Mean scores for each functional outcome met return-to-sports criteria 6 and 12 months postoperatively. Frequency counts of individual data, however, indicated that 5% of noncopers passed RTS criteria at 3, 48% at 6, and 78% at 12 months after surgery.

CONCLUSION

Functional outcomes suggest that a subgroup of noncopers require additional supervised rehabilitation to pass stringent criteria to return to sports.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Therapy, level 2b.

Keywords: ACL, knee, outcomes measures, rehabilitation

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is frequently injured and is the most prevalent structure reconstructed in an athlete’s knee.34 After an acute ACL rupture, a portion of athletes learn to successfully stabilize the ACL-deficient knee and return to sports without surgery; conversely, others present with dynamic knee instability during activities as simple as gait.10,13,16,49 In the United States, athletes with an acutely unstable knee are typically counseled to undergo surgical reconstruction with hopes of protecting the knee joint from further damage and increasing the likelihood of returning to preinjury activity levels.4,38,44 However, surgery does not guarantee protection against further joint degradation,32,67 nor does it assure a return to preinjury activity levels. Therefore, investigating whether alternative therapeutic interventions allow for improved knee function following ACL reconstruction is warranted.

Validated decision-making criteria are used to prospectively classify athletes as surgical candidates (noncopers) or potential nonsurgical candidates (potential copers) after acute ACL rupture, based on knee function.16,23 Noncopers comprise the majority of athletes with ACL deficiency.23 Noncopers demonstrate abnormal walking, jogging, and stepping patterns during motion analysis testing, have poorer functional outcomes, and complain of knee instability with basic activities such as walking compared to those classified as potential copers.23,56,57 Potential copers typically have symmetrical quadriceps femoris muscle strength and can learn to successfully stabilize their knee after ACL rupture.9,17,23

Rehabilitation specialists recommend that noncopers who are level I (jumping, cutting, pivoting) and II (lateral movements, less pivoting) International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) athletes10 undergo ACL reconstruction prior to resuming their preinjury cutting and pivoting sports participation. ACL reconstruction followed by a rehabilitation protocol, however, does not provide restoration of dynamic knee stability for all individuals, as the ability to return to sports after reconstruction ranges from 43% to 92%.25,30,40,44,45,48,61 Rehabilitation experts are still challenged by those athletes who struggle to perform at the same preinjury level even after surgery and rehabilitation protocols.

Assessing return-to-sports pass rates after participating in specific rehabilitation protocols and reporting on the prognostication of athletes passing specific return-to-sports criteria after ACL rupture and reconstruction will help determine the effectiveness of the interventions. In addition, determining factors that impede passing clearly defined criteria needed to return to sports will highlight where rehabilitation specialists need to improve clinical management. Rehabilitation protocols often include quadriceps strengthening, as quadriceps strength has been shown to influence functional outcomes after ACL injury.28 However, strong evidence indicates that quadriceps strength deficits11,14,27,66 and altered movement patterns6,20,21,31 persist after ACL reconstruction. Furthermore, preoperative quadriceps weakness is predictive of postoperative function.11,14 Evidence suggests that traditional preoperative and postoperative quadriceps strength training does not assure postoperative quadriceps strength gains for all patients.26,28,31 Noncopers who receive progressive quadriceps strengthening preoperatively and postoperatively demonstrate improved quadriceps strength indices 6 months after ACL reconstruction.21 It is unknown whether clinically meaningful strength gains occurred preoperatively, whether these noncopers were able to return to preinjury sports participation postoperatively and, if they did not pass return-to-sports criteria, why they failed. Clinically meaningful strength gains are operationally defined as 3 unitless measures of change of a patient’s normalized quadriceps strength in Newtons normalized to body mass index (BMI).

A neuromuscular intervention, called perturbation training, was designed to increase neuromuscular awareness and dynamic stability in the lower extremity. 18 Benefits of perturbation training have been demonstrated in the ACL-deficient limb of potential copers who were treated nonoperatively and noncopers who received preoperative perturbation training and were tested postoperatively. 9,17,21 Potential copers moved their ACL-deficient limb more like healthy controls and were almost 5 times more likely to successfully return to sports after completing a nonoperative intervention that included perturbation training compared to those who received standard preoperative management.9,17 Noncopers who received preoperative perturbation training had an improved gait pattern when tested 6 months after ACL reconstruction; whereas those who did not receive this intervention continued to use an asymmetrical gait pattern.21 However, whether noncopers who receive perturbation training and strength training preoperatively demonstrate superior functional outcomes postoperatively is unknown. Randomized clinical trials of preoperative physical therapy interventions after ACL rupture in the noncoper cohort are sparse.21

The purpose of this randomized clinical trial was to determine effective interventions to improve readiness to return to sports postoperatively in the noncoper cohort. Specifically, we compared the effects of 2 preoperative interventions on quadriceps strength and functional outcomes. We hypothesized that a greater number of noncopers who received preoperative perturbation and strength training (PERT group) would demonstrate meaningful quadriceps strength gains after the preoperative intervention compared to the group who received strength training only (STR group); that the PERT group would demonstrate superior 3- and 6-month postoperative outcomes compared to the STR group; and that no functional differences would exist between the groups 12 months postoperatively.

METHODS

Patients

Patients with ACL deficiency between the ages of 13 and 55 years, whose ACL rupture occurred less than 10 months prior, were recruited from the University of Delaware Physical Therapy Clinic. One surgeon (M.J.A.) diagnosed all ACL ruptures or graft ruptures via clinical examinations, which were confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. Patients were eligible for the study if they were regular participants in IKDC level I or II activities10,22 for at least 50 hours per year prior to the injury22 and presented with differences in sagittal plane tibiofemoral displacement of 3 mm or greater between the 2 knees, when tested with the KT-1000 using maximal force (Med-Metric, San Diego, CA).10 Patients were excluded if a full-thickness chondral defect of 1 cm2 or greater or concomitant grade III rupture to other knee ligaments existed. This study was approved by the University of Delaware Human Subjects Review Board and each patient provided informed consent.

Sample size estimations were performed a priori using the DSS research calculator (http://www.dssresearch.com/toolkit/sscalc/size_a2.asp). Means and standard deviations from preliminary data were entered for quadriceps maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) force normalized to BMI, quadriceps strength indices, and functional hop scores, also represented as indices. Quadriceps strength and hop indices scores were calculated using the raw force and hop values, respectively, from the involved limb/uninvolved limb expressed as a percentage. Clinically meaningful differences of 3 normalized units of quadriceps force and differences of 5% on quadriceps indices and hop score indices were used. Based on statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences, 16 noncopers were needed per group to compare functional differences over time.

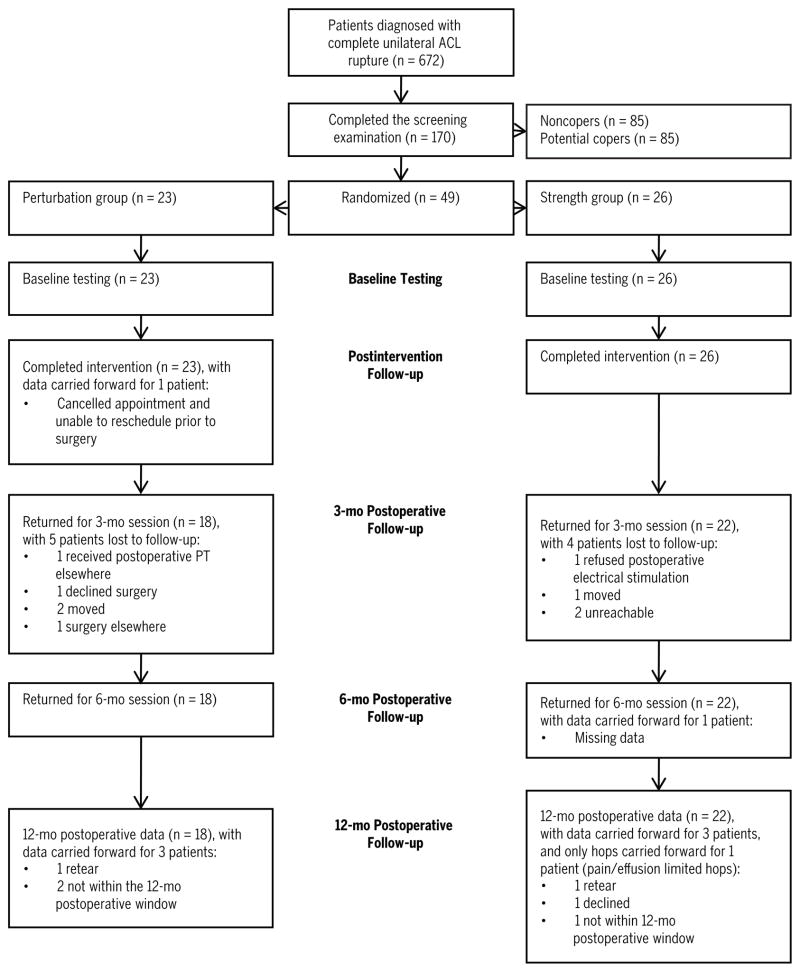

Forty-nine patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups using a randomization calculator. No blocking or group force techniques were used. The flow diagram (FIGURE 1) describes how patients were tracked throughout the study. Nine patients completed the preoperative intervention and were not followed postoperatively. Therefore, 40 patients, classified as noncopers, with an average age of 28.4 years (29 males, 11 females) were randomly assigned to a PERT group (n = 18; 12 males, 6 females) or a STR group (n = 22; 17 males, 5 females) and followed for 1 year after ACL reconstruction. All patients were screened and classified as noncopers according to the University of Delaware’s protocol,16 an average ± SD of 8.8 ± 8.3 weeks after their injury. The testing sessions and preoperative and postoperative interventions were conducted at the University of Delaware’s Physical Therapy Clinic. Licensed physical therapists were trained to systematically obtain data on variables of interest and on proper administration of the intervention protocols. Physical therapists were tested in competency prior to administering services to our patients and performing data collections. Procedural reliability was assessed for each therapist after the completion of the preoperative rehabilitation using a procedural reliability check list. Patient charts were reviewed to assure that each strengthening exercise and perturbation exercise (if applicable) was documented as performed for a randomly chosen preoperative rehabilitation session. Reliability of 85% was required for inclusion; none had procedural reliability below 85%.

FIGURE 1.

Cohort flow chart. Abbreviations: ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; PT, physical therapy. *Retear indicates patients who reruptured their graft after recruitment into the study.

Preoperative Intervention

Each patient received 10 preoperative physical therapy sessions administered between 2 and 5 times per week at the University of Delaware Physical Therapy clinic. Frequency of the preoperative intervention was based on scheduling availability, training response, and time line prior to surgery. During the intervention phase, additional sessions were provided for 3 patients to treat impairments (eg, effusion, pain) but were not counted as 1 of the mandatory 10 exercise sessions, as neither strength nor perturbation training were performed. No patients performed exercises for their lower extremities outside of physical therapy, and there was no home exercise component during the preoperative intervention phase of the study. Patients in both the STR group and the PERT group participated in the same strength training, while the PERT group also received a specialized form of neuromuscular training called perturbation training.

Strength Training

The quadriceps strength-training protocol was based on the American College of Sports Medicine guidelines,29 and only the involved limb was exercised. Patients performed high-intensity, low-repetition, non–weight-bearing and weight-bearing exercises, step-downs for neuromuscular control, and concentric/eccentric phases of the quadriceps muscle contractions using an isokinetic spectrum protocol. If the quadriceps index was less than 80%, neuromuscular electrical stimulation complemented the strengthening protocol.35 The intensive strength-training protocol was designed to encourage quadriceps muscle soreness in response to the exercise routine and to promote quadriceps strength gains.

Exercise intensity was based on achieving a percentage of the 1-repetition maximum (1RM). Patients’ involved limb MVIC force output from the Kin-Com dynamometer (Chattanooga Corp, Chattanooga, TN) was used to estimate starting weight for the single-limb 1RM testing. Patients’ self-reported estimates of maximal effort and trial and error were used to determine a true 1RM. A successful 1RM test was achieved when the patient was able to demonstrate control of the velocity of the weight for a 4-second count during the concentric and eccentric phases of the lift (equal to approximately 60°/s). 1RM testing was conducted on alternating sessions and was used to progress the weight program. Patients performed 3 sets of 6 repetitions of single-limb leg press (FIGURE 2) and knee extension (FIGURE 3) machines at 75% of their 1RM. All repetitions on the leg press and knee extension machines were performed using an 8-second count through 0° to 100° of knee range of motion, with cues from the physical therapist to assure maintenance of proper control and form. A 30- to 60-second rest between sets and 1 to 3 minutes of rest between exercises were provided to minimize the effects of fatigue on task performance.

FIGURE 2.

All leg press 1-repetition maximum testing and exercise were performed through an arc of motion of 0° to 100°.

FIGURE 3.

All knee extension 1-repetition-maximum testing and exercise were performed through an arc of motion of 0° to 100°.

Starting step height for the step-downs was determined by the greatest height at which the patient could demonstrate proper technique, as determined by the treating therapist. Maintenance of a level pelvis with the knee aligned correctly over the foot, a cadence of 4 seconds to ascend and 4 seconds to descend, and controlled heel contact with the floor were considered proper technique. Patients were progressively challenged during step-downs by increasing the step height, controlling only their body weight with no external weights used. Lateral and forward step-downs were performed. Step height was increased by 5.1 cm, as tolerated, with a maximum height of 35.6 cm. Initially, patients performed 3 sets of 10 repetitions of lateral step-downs only. Forward step-downs, using the same progression, were introduced when adequate performance of the lateral step-down task on a 15.2-cm step was achieved. Lateral step-downs were discontinued when the patient could perform 10 repetitions 3 times on the 20.3-cm step, at which time patients continued with forward step-downs only. Step-downs were performed using an 8-second count through the range of motion, with cues from the physical therapist to assure maintenance of proper control and form.

Lastly, patients performed isokinetic exercises. During the isokinetic spectrum protocol, speed was controlled by the constant concentric and eccentric effort of the patients’ knee extensors to move through knee extension and flexion, respectively. The isokinetic training spectrum programmed into the KinCom started with a set at 60°/s, increasing each subsequent set by 30°/s speed increments up to 180°/s, after which, sets were performed at progressively lower speeds by decrements of 30°/s, ending at 60°/s. Patients were instructed to extend the knee as forcefully as possible throughout each set of the isokinetic spectrum (10 repetitions at each speed). Each set was followed by a 30-second rest and followed by the next set at a different isokinetic speed. Real-time visual representation of the force output was used to encourage maximal volitional effort.

Perturbation Training

We followed the University of Delaware guidelines for perturbation training.18 The PERT group performed perturbation exercises17 prior to the strengthening exercises. Patients maintained balance on the support surface, while an experienced clinician administered purposeful manipulations of the support surfaces. The order of each condition was randomized prior to each session. Patients completed 3 sets of approximately 1-minute sessions on each of the 3 conditions shown in FIGURE 4 (ONLINE VIDEOS). Speed, amplitude, and direction of the applied force were progressed based on the patient’s ability to demonstrate proper muscular responses to assure motor learning during each task.16 Progression included anticipated to unanticipated movements, increasing speed and amplitude of movement, switching from feed-forward to feed-back verbal and tactile cues, and performing sport-specific activity while perturbations were applied.17 Detailed guidelines for the progression of the perturbation training are described elsewhere.18

FIGURE 4.

Platforms used for the perturbation training. Rocker board (A), roller board with caster wheels under each corner (B), and a stable platform aside the roller board to keep the patient’s feet at equal height (C). The order of the use of the platforms was randomized prior to each session. During the first session, patients began on both limbs and progressed to single-limb activities for the first 2 platforms (A and B) (ONLINE VIDEOS).

The goal of perturbation training was to educate the patient to elicit selective muscle reactions of supporting knee musculature in response to the force administered to the platform. The treating therapist would perturb the platforms, while using verbal and tactile cues to guide patient positioning and response to the movements of support surfaces. The patient was encouraged to respond to the direction and force of the perturbation with purposeful muscle responses that would prevent large excursions of the support surface. Gross muscular co-contraction and preparatory stiffening of the joint were discouraged and addressed with additional cues from the therapist.

Surgery and Postoperative Intervention

After completion of the 10 preoperative physical therapy sessions, all patients underwent arthroscopically assisted ACL reconstruction by a single orthopaedic surgeon (M.J.A.), using a double-loop semitendinosus gracilis (4-bundle) autograft or a tibialis anterior muscle or Achilles tendon allograft. Similar graft placement was used for all surgeries. All patients received the same postoperative rehabilitation program35 at the University of Delaware Physical Therapy Clinic, regardless of preoperative group assignment. Patients did not receive a standardized dose of postoperative physical therapy. The duration of each session, frequency of visits, and length in terms of weeks were based on the patient’s needs and the ability to meet clinical milestones established by the University of Delaware Physical Therapy clinic. Our criterion-based postoperative rehabilitation protocol included impairment resolution, progressive quadriceps strengthening, including high-intensity neuromuscular electrical stimulation until a quadriceps index of 80% was achieved, and neuromuscular training to achieve progression through a walk/jog program and agility protocol.35 Perturbation training was not administered postoperatively. Quadriceps strength indices, knee effusion grades, and soreness rules were used as guidelines to assure that patients were progressively challenged in a safe manner.35 Few patients were formally discharged after 2 months of postoperative physical therapy. The majority of patients continued to receive physical therapy to advance their home exercise program and progress toward achieving clinical milestones needed to pass return-to-sports criteria until the 6-month postoperative time frame. Some patients continued to attend physical therapy appointments every 2 to 4 weeks until the 12-month postoperative follow-up session, as they had not passed criteria necessary to return to sports participation. If the patient’s healthcare provider denied physical therapy payment that the supervising physical therapist deemed necessary, then funding for physical therapy services were covered by the principal investigator’s grant (L.S.M.).

Return to Sports

Readiness to return to sports was determined using strict clinical milestones established by the University of Delaware.16 Athletes were eligible to test for return-to-sports readiness as early as 12 weeks after ACL reconstruction if impairments had resolved and they met the criteria required to complete hop tests (TABLE 1). The exception being patients with a prior ACL reconstruction were not allowed to perform hop testing until 16 weeks after their ACL revision surgery per the University of Delaware’s clinical guidelines. 35,39 Functional testing to determine return-to-sports readiness included assessing quadriceps strength, unilateral hop scores, and self-reported knee function. Based upon the work of Fitzgerald and colleagues,18 we defined passing return-to-sports criteria as achieving 90% or greater on all functional assessments, which were the quadriceps strength index, all 4 hop indices (the single hop, crossover hop, triple hop, and 6-meter timed hop), the Knee Outcome Survey activities of daily living scale (KOS-ADLS), and a global rating scale of overall knee function.

TABLE 1.

Criteria to Perform Hop Testing After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

| ≥12 wk postoperative | Full knee range of motion |

| ≤1+ knee effusion | Pain-free hopping |

| ≥80% quadriceps strength index | Normal gait |

Quadriceps strength was measured using a burst superimposition technique to assure maximum volitional force output. 62 Quadriceps index was calculated as the maximum force output of the involved limb divided by the uninvolved limb, expressed as a percentage.62 Hop testing, first described by Noyes and colleagues, 46 consisted of the single hop, crossover hop, and triple hop tests for distance, and the 6-meter timed hop test for speed. Hop scores were expressed as a measurement of limb symmetry and have been shown to be reliable and valid measurements in a population of those who have had ACL reconstruction.5,52

Self-reports of knee function and symptoms were determined using a global rating scale and KOS-ADLS questionnaire. The global rating scale and KOS-ADLS questionnaires were administered after the completion of the hop testing to allow patients to better perceive their functional status. The global rating scale is a single question that rates the perceived level of knee function based on a scale from 0% to 100%, with lower numbers representing poorer function and 100 being the ability to perform all preinjury activities, including sports, without limitation.24 The KOS-ADLS is a 14-item questionnaire inquiring about symptoms and functional tasks and how well one is able to perform the activity, with lower scores representing greater functional limitations. 24 The KOS-ADLS has been shown to be reliable in a population of athletes with knee injury. 37 Furthermore, the KOS-ADLS is a reliable, valid, and responsive measure for assessing functional limitations of the knee, with high internal consistency and test-retest reliability.24 Once patients achieved at least 90% on the quadriceps index, all 4 hop indices, and the 2 ques tionnaires, they were cleared to begin reintegration into their respective level I or II sports.10 The University of Delaware’s Physical Therapy clinic recommends that on passing return-to-sports criteria the athlete move toward full sports participation in a progressive fashion that may take days to months.35 If our patients failed any of the 7 return-to-sports criteria, a home exercise program was established to address the problem and they were retested no sooner than 24 hours later, until they achieved a passing score on all return-to-sports criteria.

Data Management and Analysis

Variables of interest were quadriceps strength (involved limb force and quadriceps indices), hop scores (represented as indices), KOS-ADLS, global rating scale of knee function, factors limiting patients’ ability to hop, and criterion limiting patients’ ability to pass return-to-sports criteria. Means were determined for the quadriceps index, the single hop, crossover hop, triple hop, and 6-meter timed hop indices, the KOS-ADLS, and the global rating scale at baseline (screening examination) and 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Quadriceps strength in the involved limb was normalized to BMI and reported at baseline, following the preoperative intervention, and at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Quadriceps strength differences were calculated from baseline to each follow-up testing session to provide evidence on clinically meaningful strength gains (defined a priori) over time.

Quadriceps strength gains in the involved limb were documented as an increase, no change, or a decrease in strength. A clinically meaningful decrease in quadriceps strength was defined as a force reduction of greater than 3 normalized units of quadriceps strength (force [N]/BMI [kg/m2]) over time. No meaningful change in strength occurred when values remained between ±3 normalized units of force. A clinically meaningful increase in strength was defined as an increase of greater than 3 normalized units of force.

Dichotomous variables of pass (>90%) and fail (<90%) were determined for each return-to-sports criterion (quadriceps index, each hop index, and each self-reported questionnaire score) at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. If a patient was not cleared to perform hop testing (per criteria in TABLE 1), reasons for not hopping were recorded and counted. Pass and fail was documented and counted for each return-to-sports criterion and for achieving a total pass or fail for all return-to-sports criteria at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery.

The functional data were not normally distributed; therefore, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to determine if there were differences in the means between the groups at each postoperative time frame. Chi-square tests were used to compare the frequency counts between groups of those who (1) achieved clinically meaningful strength gains, (2) were and were not cleared to hop, (3) pass/fail each return-to-sports criterion, and (4) pass/fail all return-to-sports criteria. Comparisons were also made between groups to determine if the reasons limiting hop testing and return-to-sports readiness were different between groups at each postoperative time frame. A Fisher exact test was used instead of the chi-square if the number of patients was less than 5.

RESULTS

Gender, age, BMI, quadriceps strength indices, time from ACL injury to the screening examination, and the time to complete the preoperative intervention were not statistically different between the groups (TABLE 2). FIGURE 1 illustrates when patients were unable to attend testing sessions and how data were accounted for during the analyses. Two patients, who were injured prior to the 12-month follow-up session (1 from each group), had passed all return-to-sports criteria prior to the injury and tore their graft during a contact injury while playing their respective sports (rugby and flag football) (FIGURE 1).

TABLE 2.

Patients’ Demographics for the Perturbation (PERT) and Strength (STR) Groups*

| PERT | STR | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 27.1 ± 10.2 (15–48) | 29.5 ± 10.8 (14–46) | .459 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.6 ± 6.4 (22.4–44.8) | 28.4 ± 3.8 (21.5–35.3) | .957 |

| Quadriceps index (%) | 88.6 ± 9.9 (78.9–114.0) | 87.9 ± 15.5 (62.0–130.9) | .396 |

| Injury to screen (wk) | 6.5 ± 6.1 (1.0–28.0) | 10.6 ± 9.4 (1.5–37.0) | .058 |

| Completed preoperative treatment (wk) | 3.1 ± 0.9 (2.0–4.5) | 4.0 ± 1.9 (2.0–10.0) | .092 |

| Gender | 12 males; 6 females | 17 males; 5 females | .347 |

Values are mean ± SD (range) unless otherwise indicated.

Clinically Meaningful Quadriceps Strength Changes

The number of patients who obtained clinically meaningful quadriceps strength gains were not different between the groups after the preoperative intervention, or at 3, 6, and 12 months after ACL reconstruction (TABLE 3). Of the 40 patients, 1 in the PERT group and 6 in the STR group received preoperative neuromuscular electrical stimulation. This was not statistically different between the groups (P = .081). All patients received postoperative electrical stimulation until their quadriceps index was at least 80%.

TABLE 3.

Comparisons Between Groups for the Number of Subjects With a Clinically Meaningful Change in the Involved Limb’s Quadriceps Strength From Baseline to Each Follow-up Testing Session

| PERT | STR | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline to postintervention | .583 | ||

| Decrease* | 3 | 5 | |

| No change | 5 | 9 | |

| Increase | 9 | 8 | |

| Baseline to 3 mo postoperative | .311 | ||

| Decrease | 6 | 4 | |

| No change | 3 | 8 | |

| Increase | 8 | 9 | |

| Baseline to 6 mo postoperative | .323 | ||

| Decrease | 3 | 1 | |

| No change | 7 | 7 | |

| Increase | 8 | 14 | |

| Baseline to 12 mo postoperative | .295 | ||

| Decrease | 1 | 2 | |

| No change | 5 | 2 | |

| Increase | 12 | 18 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PERT, perturbation group; STR, strength group.

Decrease indicates a decrease in quadriceps strength of more than 3 normalized units of quadriceps strength [force (Newtons)/BMI (kg/m2)]. No change indicates those patients whose strength remained between ±3 normalized units. Increase indicates those with an increase in strength of at least 3 normalized units of force.

Group Comparisons for Mean Differences in Functional Outcomes

Mean values are presented for each group at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery in TABLE 4. There were no significant differences in mean values for any of the functional outcome measures between groups 3 months after ACL reconstruction. Three months after surgery, the mean values did not approach 90% for the hop tests scored for distance and the global rating scale of knee function, whereas the quadriceps index, timed hop index, and KOS-ADLS scores were close to or surpassed the 90% value needed to pass return-to-sports criteria. Six months after surgery, the means of all functional outcomes were at least 90% for all return-to-sports criteria though the ranges of scores continued to be large for both groups. The KOS-ADLS and global rating scores were significantly greater in the PERT group 6 months postoperatively. Twelve months after surgery, the timed hop scores were significantly greater in the STR group. The range of scores for the timed hop test were considered to be symmetrical values for the STR group, as the involved limbs had scores of at least 90% of those of the uninvolved limbs; whereas the ranges of scores for those in the PERT group included values below 90%. The mean values continued to remain above 90% for all return-to-sports criteria 12 months after surgery.

TABLE 4.

The 7 Return-to-Sports Criteria Comparing the PERT and STR Groups at Each Follow-up Testing Session*

| PERT | STR | P Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mo postoperative | |||

| Quadriceps strength index | 88.7 (64.9–118.9) | 92.7 (62.1–128.3) | .607 |

| Single hop | 83.7 (57.3–107.0) | 83.1 (75.2–95.6) | .569 |

| Crossover hop | 81.7 (65.9–103.6) | 85.6 (64.0–100.0) | .518 |

| Triple hop | 82.4 (63.6–99.5) | 86.4 (77.0–91.3) | .362 |

| 6-meter timed hop | 89.2 (66.2–110.6) | 89.8 (71.0–106.3) | .790 |

| KOS-ADLS | 91.7 (71.4–98.6) | 90.9 (71.4–98.6) | .507 |

| Global rating scale | 86.4 (69.0–99.0) | 82.1 (50.0–95.0) | .342 |

| 6 mo postoperative | |||

| Quadriceps strength index | 95.7 (70.3–117.6) | 93.0 (66.7–112.6) | .626 |

| Single hop | 92.6 (81.2–100.0) | 92.9 (73.0–108.1) | .443 |

| Crossover hop | 93.1 (79.4–108.0) | 95.2 (76.8–112.3) | .435 |

| Triple hop | 93.5 (81.1–103.4) | 95.0 (81.4–101.2) | .265 |

| 6-meter timed hop | 95.2 (84.9–106.3) | 98.2 (86.2–108.5) | .226 |

| KOS-ADLS | 97.9 (90.0–100.0) | 95.9 (87.1–100.0) | .029† |

| Global rating scale | 94.3 (80.0–100.0) | 90.0 (70.0–100.0) | .047† |

| 12 mo postoperative | |||

| Quadriceps strength index | 98.7 (84.4–124.7) | 98.1 (78.7–128.0) | .885 |

| Single hop | 94.9 (74.2–107.6) | 98.0 (85.1–107.8) | .259 |

| Crossover hop | 96.3 (76.0–116.0) | 97.7 (73.0–111.0) | .412 |

| Triple hop | 95.4 (82.5–101.0) | 97.6 (89.0–107.0) | .278 |

| 6-meter timed hop | 95.2 (86.6–105.0) | 100.3 (91.0–111.2) | .013† |

| KOS-ADLS | 97.1 (82.9–100.0) | 97.5 (81.4–100.0) | .997 |

| Global rating scale | 96.2 (90.0–100.0) | 92.9 (70.0–100.0) | .218 |

Abbreviations: KOS-ADLS, Knee Outcome Survey activities of daily living scale; PERT, perturbation group; STR, strength group.

Values are mean (range).

P<.05.

Group Comparisons for Frequency Counts of Functional Outcomes

Frequency counts are displayed for each group at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery in TABLE 5. There were no significant differences in frequency counts between groups except for the global rating scale values at 6 and 12 months after surgery. A greater percentage of patients in the PERT group passed the global rating scale criterion: 89% (16/18) passed in the PERT group compared to 59% (13/22) in the STR group at 6 months (P = .025) after surgery, and 100% (18/18) passed in the PERT group compared to 77% (17/22) in the STR group (P = .04) 12 months after surgery (TABLE 5). Patients who passed return-to-sports criteria were tested again at each postoperative follow-up session to assess whether functional outcomes were maintained over time. Three athletes demonstrated a decline in functional status at the testing session 12 months postsurgery: 2 in the STR and 1 in the PERT group. Quadriceps indices were not calculated for 3 patients 6 months after surgery and 4 patients 12 months after surgery, as the force output of each limb exceeded the capacity of the KinCom. The number of patients who passed all return-to-sports criteria was not different between the groups at any postoperative follow-up session. Only 2 patients (5%) passed all return-to-sports criteria (1 from each group) at 3 months, 19 patients (48%) at 6 months, and 31 patients (78%) at 12 months after surgery.

TABLE 5.

Results for the Group Comparisons of Those Who Pass and Fail Each Criterion Necessary to Be Cleared to Return to Sports

| PERT

|

STR

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pass | Fail | No Data | Pass | Fail | No Data | P Values | |

| 3 mo postoperative | |||||||

| Quadriceps strength index | 11 | 6 | 1 | 11 | 10 | 1 | .739 |

| Single hop | 4 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 13 | .192 |

| Crossover hop | 2 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 13 | .198 |

| Triple hop | 2 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 13 | .435 |

| 6-meter timed hop | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 13 | .180 |

| KOS-ADLS | 11 | 6 | 1 | 17 | 4 | 1 | .522 |

| Global rating scale | 8 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 14 | 1 | .683 |

| Return to sports† | 1 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 1 | .978 |

| 6 mo postoperative | |||||||

| Quadriceps strength index | 12 | 5 | 1 | 14 | 6 | 2 | .914 |

| Single hop | 13 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 7 | 1 | .452 |

| Crossover hop | 13 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 5 | 2 | .885 |

| Triple hop | 13 | 3 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 2 | .736 |

| 6-meter timed hop | 12 | 4 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 2 | .477 |

| KOS-ADLS | 17 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 1 | .653 |

| Global rating scale | 16 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 9 | 0 | .025* |

| Return to sports† | 9 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 12 | 0 | .480 |

| 12 mo postoperative | |||||||

| Quadriceps strength index | 13 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 5 | 1 | .330 |

| Single hop | 15 | 3 | 0 | 19 | 2 | 1 | .526 |

| Crossover hop | 15 | 3 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | .311 |

| Triple hop | 16 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | .499 |

| 6-meter timed hop | 17 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 1 | .360 |

| KOS-ADLS | 17 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | .653 |

| Global rating scale | 18 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 5 | 0 | .040* |

| Return to sports† | 14 | 4 | 0 | 17 | 5 | 0 | .636 |

Abbreviations: KOS-ADLS, Knee Outcome Survey activities of daily living scale; PERT, perturbation group; STR, strength group.

P<.05.

Only 1 patient in each group passed all return-to-sports criteria at 3 months, 19 in total at 6 months, and 31 in total at 12 months postoperatively.

Who Were Not Able to Hop and Why

There were no significant differences between groups in the number of patients who were not allowed to hop at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery. Impairments restricting patients from hopping are listed in TABLE 6. Three months after surgery, 19 patients did not perform hop testing. One patient presented with effusion and a quadriceps strength index of less than 80%, with all other patients limited by only 1 impairment. Six months after surgery, 3 patients were not cleared to perform hop testing. One patient was cleared to hop at 6 months and did not pass return-to-sports criteria. This patient was not cleared to hop at 12 months due to a knee effusion grade of greater than 1+, likely due to noncompliance with his effusion management secondary to work commitments (manual laborer) and family responsibilities.

TABLE 6.

Number of Patients Who Were Not Allowed to Hop and Reasons for Not Being Cleared to Hop*

| 3 mo Postoperative

|

6 mo Postoperative

|

12 mo Postoperative

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERT (n = 7) | STR (n = 12) | PERT (n = 1) | STR (n = 2) | PERT (n = 1) | STR (n = 0) |

| 1 effusion and low QI | 6 effusion | 1 low QI | 1 pain | 1 effusion | 0 effusion |

| 3 low QI (4 total) | 1 low QI 0 | refused | 1 refused | ||

| 0 pain | 2 pain | ||||

| 1 meniscal repair | 1 meniscal repair | ||||

| 2 retear† | 2 retear† | ||||

Abbreviations: PERT, perturbation group; QI, Quadriceps strength index; STR, strength group.

No difference between groups.

Retear indicates patients who sustained a rupture of the graft and underwent a second anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Reasons Noncopers Did Not Return to Sports

TABLE 7 indicates the number of patients who failed to pass all 7 return-to-sports criteria at each postoperative time frame and the reasons for failing. Three months after surgery, patients achieved less than 90% on quadriceps strength indices scores, hop testing, the KOS-ADLS, and the global rating scale of knee function. There were no differences in the reasons limiting performance between groups at this time. Six months after surgery, scores less than 90% on the quadriceps strength indices, hop indices, and global rating scale values again restricted patients from passing return-to-sports criteria, with only 1 patient not achieving the KOS-ADLS criterion. There were a significantly greater number of patients who rated their global knee function less than 90% in the STR group compared to the PERT group 6 months after ACL reconstruction. Twelve months after surgery, patients failed to pass return-to-sports criteria due to a number of reasons. However, out of the 8 patients who failed, 6 demonstrated quadriceps strength indices of less than 90%. There were no differences between groups in the reasons patients did not pass return-to-sports criteria at 12 months, nor were there any group differences in the total number of patients who failed to pass return-to-sports criteria at any postoperative time frames (TABLE 7).

TABLE 7.

Reasons for Failing Return-to-Sports Criteria Between Groups*

| PERT | STR | P Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mo postoperative | |||

| Total failed RTS criteria (n)† | 9 | 8 | .292 |

| Quadriceps strength index | 6 | 7 | .410 |

| Hops | 7 | 6 | .680 |

| KOS-ADLS | 5 | 3 | .519 |

| Global rating | 8 | 8 | .427 |

| 6 mo postoperative | |||

| Total failed RTS criteria (n)† | 7 | 10 | .275 |

| Quadriceps strength index | 5 | 4 | .761 |

| Hops | 5 | 6 | .941 |

| KOS-ADLS | 0 | 1 | .595 |

| Global rating | 1 | 7 | .032‡ |

| 12 mo postoperative | |||

| Total failed RTS criteria (n)† | 3 | 5 | .472 |

| Quadriceps strength index | 3 | 3 | .418 |

| Hops | 2 | 1 | .391 |

| KOS-ADLS | 0 | 1 | .645 |

| Global rating | 0 | 4 | .092 |

Abbreviations: KOS-ADLS, Knee Outcome Survey activities of daily living scale; PERT, perturbation group; RTS, return to sports; STR, strength group.

No difference between groups.

A patient may have failed more than 1 criterion at any given time point.

P>.05.

DISCUSSION

Outcome measures in how the knee responds vary considerably in noncopers preoperatively and at 3, 6, and 12 months after ACL reconstruction. Our hypothesis that 10 sessions of perturbation training prior to surgery would produce superior functional outcomes was not fully supported by this work. The group means and individual findings are important, as they impact our clinical decision making in recommending when athletes can safely return to sports postoperatively.

We evaluated a cohort with the worst functional status after acute ACL rupture56 and suspected that few noncopers would pass clinical milestones required to return to sports at 3 months postoperatively. In fact, only 2 patients passed all 7 return-to-sports criteria at this time. The University of Delaware follows clinical milestones, dependent on quadriceps strength, soreness, and effusion rules, which indicate that a walk/jog program can begin 2 months after ACL reconstruction.35 Agility training can be introduced 3 months after surgery if the athlete tolerates jogging without an increase in signs or symptoms in the knee.35 Athletes were recently cleared to hop 3 months after surgery, which may account for our low hop indices.

More promising was that 55% of our patients demonstrated symmetrical quadriceps strength 3 months after surgery. Furthermore, 43% of noncopers demonstrated clinically meaningful quadriceps strength gains preoperatively without an intact ACL. Noncopers have been traditionally weaker preoperatively13,55 and have difficulty gaining quadriceps strength postoperatively.31 Our favorable strength outcomes may be due to the inclusion of our intensive, progressive preoperative and postoperative quadriceps strengthening protocol. For example, the high-intensity neuromuscular electrical stimulation protocol used on the involved limbs in our patients in this study has been shown to more effectively increase quadriceps strength, compared to volitional exercises alone.12,63–65 Patients who were not cleared to return to sports activities due to weakness or additional impairments were instructed on how to address the factors limiting their ability to pass return-to-sports criteria with a comprehensive home exercise program. An independent home program is paramount to address these persistent impairments, as patients are often discharged from formal physical therapy around this 3-month postoperative time frame.

Six months after surgery, our quadriceps strength mean values were greater than 90%, and only 10% presented with a meaningful quadriceps strength decline compared to baseline. Others who compared preoperative quadriceps strength to postoperative values reported (1) a 12% quadriceps strength deficit 6 months postoperatively,27 (2) that the greatest quadriceps strength deficits occurred 6 months after surgery,11 and (3) that a significant decline existed in quadriceps strength from preoperative values to 6 months postoperatively.53 Furthermore, Carter and colleagues7 reported that the majority of their patients continued to present with quadriceps strength asymmetry 6 months after ACL reconstruction, whereas only 35% of our noncopers presented with asymmetrical quadriceps indices. Again, our quadriceps strength achievements at 6 months may be attributed to our intensive preoperative and postoperative quadriceps strength-training protocol.

Our mean scores on all 4 hop indices were greater than 90% 6 months after ACL reconstruction. Our results are superior to the triple (the strength and neuromuscular groups, 83.1% and 88.5%, respectively) and single (strength and neuromuscular groups, 81.0% and 84.9%, respectively) hop scores reported 6 months postoperatively by Risberg and colleagues.53 The postoperative protocol of the Risberg et al53 study was similar to that administered to our noncoper cohort. Therefore, our superior quadriceps strength and hop test results compared to the results of Risberg and colleagues53 support the use of our preoperative intervention in conjunction with postoperative rehabilitation after ACL rupture.

Though our mean quadriceps strength symmetry values surpass 6-month postoperative values reported in the literature, 11,27,66 more than half of our noncopers did not pass our return-to-sports criteria 6 months after ACL reconstruction. Our high mean scores for each return-to-sports criterion contrast those of the 52% of patients who were unable to pass all return-to-sports criteria. Our 6-month data highlight the importance of testing athletes on an individual basis and not using time-based criteria as guidelines for readiness to return to sports. Perhaps our rates of passing return-to-sports criteria reflect our very strict criteria. Our standardized return-to-sports criteria of collectively passing all 7 functional measures were more rigorous than criteria used by others.43,60,70 There are no universally accepted functional guidelines for objectively determining when an athlete is ready to safely return to sports participation following an ACL reconstruction.8,35,43,44 Criterion values to define limb symmetry are also debatable, ranging from 70% to 90%.2,19,35,42,43,46,59,68,69 Our stringent criteria to return to sports were set at the high end of the normative values to assure that our athletes moved symmetrically and did not favor the involved limb. Furthermore, achieving a quadriceps index of at least 90% after ACL reconstruction has resulted in athletes walking and jogging similarly to healthy controls.31 We advocate using strict return-to-sports criteria and testing athletes on an individual basis prior to clearing athletes to return to level I and II sports.

Twelve months after surgery, 22% of our noncoper cohort was still not cleared to return to sports. Our 12-month postoperative return-to-sports rate of 78% is similar to the 81% return-to-sports rate reported by Smith and colleagues.61 However, of the 81% who returned to sports in the Smith and colleagues study,61 21% of athletes reported competing despite major functional impairments in the involved knee 12 months after ACL reconstruction. Nakayama and colleagues45 indicated a 92% success rate for return to sports at 12 months, but only 80% scored their knee as normal or nearly normal on the IKDC survey. Furthermore, Lee and colleagues30 reported that complaints of an unstable knee and pain restricted sports participation in nearly 20% of patients 5 years after ACL reconstruction.

Low quadriceps strength indices continued to restrict patients’ ability to pass return-to-sports criteria 12 months after surgery. Unexpectedly, 6 of 8 patients who failed return-to-sports criteria at this time, demonstrated quadriceps strength deficits. All of our patients followed a high-intensity, low-repetition strengthening program that focused on increasing the involved limb quadriceps force production, yet certain patients did not achieve quadriceps strength symmetry between limbs. Our patients were instructed to perform non–weight-bearing and weight-bearing exercises on the involved limb, to focus on symmetrical effort on the involved limb during bilateral weight-bearing exercises, and to avoid favoring of the involved limb during transitions (eg, sit to stand, stand to sit, getting in and out of cars, ascending and descending stairs, and during jogging and agilities). Conceivably, certain patients may lack the ability to demonstrate quadriceps strength symmetry after input from the native ACL is compromised during rupture. Others have also reported quadriceps weakness in the involved limb at this postoperative time frame.11 Quadriceps strength deficits of nearly 20% have been reported 1 year after ACL reconstruction,11 with quadriceps strength deficits of 10% continuing up to 2 to 4 years after surgery.33 Quadriceps strength deficits that continue despite progressive strength training remain an enigma.

Clearly, quadriceps strength plays a role in returning to preinjury status. Though quadriceps strength correlates with functional stability,28 research indicates that strength is not the only determinant in dynamic knee stability.54 Demonstrating at least 90% quadriceps strength indices, no pain with hopping, and an effusion grade of less than 1+ did not assure that the patient passed all return-to-sports criteria. Functional hop scores and self-reported scores of knee function also restricted a patient’s ability to pass our strict return-to-sports criteria. Though the group that received preoperative perturbation training did not demonstrate improved return-to-sports outcomes, global ratings of knee function were superior compared to the strengthening group at 6 and 12 months after surgery. Risberg et al53 also reported higher scores of global knee function after neuromuscular training compared to a traditional strengthening protocol.

The lack of support for our hypothesized group differences and the variability reported in quadriceps strength and return-to-sports results may be multifactorial. Firstly, gains from preoperative perturbation training may not have carried over postoperatively due to the impact of surgery. Secondly, noncopers may respond differently to perturbation training than potential copers. Thirdly, we may not be triggering the neurological adaptation for all noncopers to develop a stable knee and symmetrical quadriceps force production in the absence of feedback from their native ACL. Lastly, large variability in preoperative strength gains and postoperative outcomes suggests individualized results in an athlete’s knee responsiveness to therapeutic interventions. The large range of functional outcome measurements demonstrated by this cohort throughout the postoperative testing sessions supports the notion of subgroups within the noncoper cohort.

Limitations in this study were the inability to conclude whether noncopers would respond differently after preoperative perturbation training compared to potential copers, as our noncopers went on to have ACL reconstructions after completing the 10 preoperative perturbation sessions. Future work following a group of noncopers who receive perturbation training in addition to progressive strength training and opt for nonsurgical management is warranted to eliminate the confounding effects of surgery on treatment response. Augmenting the postoperative rehabilitation protocol and following noncopers’ response to treatment would help to determine whether superior functional outcomes are attainable or if certain knees are untreatable. Perhaps, when agility training is tolerated, postoperative perturbation training or more aggressive neuromuscular interventions may be needed to address the impaired functional status in the portion of patients who were unable to return to preinjury sports participation with our current interventions. Future studies are also required to investigate why outcomes are so variable in noncopers, whether subgroups exist in knee responsiveness postsurgery, and which factors influence functional outcomes in a cohort of noncopers.

Surgeons strive to ensure that surgical grafts are of good quality, tunnels are well placed, fixation is adequate, and postoperative extension is achieved, while rehabilitation specialists strive for timely impairment resolution and full knee extension preoperatively and postoperatively. Yet overwhelming evidence indicates that certain athletes are unable to return to sports even years after ACL reconstruction,25,30,41,44 supporting the use of functional criteria versus time-based guidelines to return athletes to sports. Despite our inclusion of a specific cohort, similar surgical procedures, and comparable postoperative care, there was large variability throughout all follow-up testing sessions. The current push toward returning athletes to sports quickly, with a staggering number of healthcare professionals recommending return to sports at 6 months after ACL reconstruction, 1–3,8,15,36,42,47,50,51,58,68,69 is of concern.

CONCLUSION

When mean scores were analyzed, noncopers demonstrated symmetrical quadriceps strength at 3 months and the ability to return to sports 6 months after ACL reconstruction; however, individual functional scores demonstrated large variability in the ability to pass return-to-sports criteria. The comparison between groups that completed 10 sessions of strength training, with perturbation training versus just strength training prior to ACL reconstruction, resulted in no significant differences in functional outcomes postoperatively, with the exception that those in the strength group hopped faster at 12 months and those in the perturbation group rated their knee function more favorably 6 and 12 months after ACL reconstruction. Noncopers may require additional time and longer supervised rehabilitation to return to preinjury function postoperatively. Certain noncopers may be unable to develop appropriate quadriceps strength symmetry after the native ACL is ruptured. A portion of the patients continued to demonstrate clinically concerning quadriceps strength deficits postoperatively, suggesting that resuming high-level sport participation may not be safe for all individuals. We recommend that clinicians evaluate athletes on an individual basis rather than use time-based criteria, as mean scores and time frames were not representative of the functional ability of this cohort’s readiness to safely return to sports per our strict criteria.

KEY POINTS.

FINDINGS

Patients underwent intensive preoperative and postoperative physical therapy, with promising functional outcomes for few athletes 3 months after surgery. However, not all high-level athletes were able to pass rigorous criteria deemed necessary to return safely to cutting and pivoting sports 1 year after surgery.

IMPLICATIONS

Rehabilitation specialists should determine whether an athlete is safe to return to sports based on functional abilities and not solely on time since injury or surgery.

CAUTION

The results from this manuscript were obtained from athletes classified as noncopers after acute injury, who were regular participants in level I and II sports.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank Dr Wendy J. Hurd for establishing the preoperative quadriceps strengthening protocol used in this study, the University of Delaware Physical Therapy Clinic for providing the physical therapy services for our patients, and our funding sources (The National Institutes of Health, Foundation for Physical Therapy, and the University of Delaware fellowship scholarship) for making this research possible.

This study was financed by grants from the NIH (R01AR048212 and S10RR022396), Foundation for Physical Therapy (PODS I and II), and University of Delaware Dissertation Fellowship. The protocol of this study was approved by the University of Delaware Human Subjects Review Board.

References

- 1.Alvarez JJR, Lopez-Silvarrey FJ, Martinez JCS, Melen HM, Arce JCL. Patient rehabilitation with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injurie of the knee. Review. Revista Internacional De Medicina Y Ciencias De La Actividad Fisica Y Del Deporte. 2008;8:62–92. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aune AK, Holm I, Risberg MA, Jensen HK, Steen H. Four-strand hamstring tendon autograft compared with patellar tendon-bone autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A randomized study with two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:722–728. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290060901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett GR, Noojin FK, Hartzog CW, Nash CR. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in females: A comparison of hamstring versus patellar tendon autograft. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:46–54. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.25974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, Fleming BC, Nichols CE. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part I. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1579–1602. doi: 10.1177/0363546505279913. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0363546505279913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolgla LA, Keskula DR. Reliability of lower extremity functional performance tests. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26:138–142. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1997.26.3.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulgheroni P, Bulgheroni MV, Andrini L, Guffanti P, Giughello A. Gait patterns after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:14–21. doi: 10.1007/s001670050018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter TR, Edinger S. Isokinetic evaluation of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: hamstring versus patellar tendon. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:169–172. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.0150161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/ar.1999.v15.0150161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cascio BM, Culp L, Cosgarea AJ. Return to play after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23:395–408. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.03.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chmielewski TL, Hurd WJ, Rudolph KS, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Perturbation training improves knee kinematics and reduces muscle co-contraction after complete unilateral anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Phys Ther. 2005;85:740–749. discussion 750–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632–644. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jong SN, van Caspel DR, van Haeff MJ, Saris DB. Functional assessment and muscle strength before and after reconstruction of chronic anterior cruciate ligament lesions. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:21–28. 28 e21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delitto A, Rose SJ, McKowen JM, Lehman RC, Thomas JA, Shively RA. Electrical stimulation versus voluntary exercise in strengthening thigh musculature after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Phys Ther. 1988;68:660–663. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eastlack ME, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Laxity, instability, and functional outcome after ACL injury: copers versus noncopers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:210–215. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199902000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eitzen I, Holm I, Risberg MA. Preoperative quadriceps strength is a significant predictor of knee function two years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:371–376. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.057059. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.057059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ejerhed L, Kartus J, Sernert N, Kohler K, Karlsson J. Patellar tendon or semitendinosus tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A prospective randomized study with a two-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:19–25. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310011401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A decision-making scheme for returning patients to high-level activity with nonoperative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:76–82. doi: 10.1007/s001670050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. The efficacy of perturbation training in nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation programs for physical active individuals. Phys Ther. 2000;80:128–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Proposed practice guidelines for nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation of physically active individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:194–203. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.4.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gobbi A, Diara A, Mahajan S, Zanazzo M, Tuy B. Patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with conical press-fit femoral fixation: 5-year results in athletes population. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s00167-001-0265-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00167-001-0265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gokeler A, Schmalz T, Knopf E, Freiwald J, Blumentritt S. The relationship between isokinetic quadriceps strength and laxity on gait analysis parameters in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:372–378. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0432-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00167-003-0432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartigan E, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Perturbation training prior to ACL reconstruction improves gait asymmetries in non-copers. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:724–729. doi: 10.1002/jor.20754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jor.20754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hefti F, Muller W, Jakob RP, Staubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1:226–234. doi: 10.1007/BF01560215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:40–47. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308190. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0363546507308190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irrgang JJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Wainner RS, Fu FH, Harner CD. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1132–1145. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvinen M, Natri A, Lehto M, Kannus P. Reconstruction of chronic anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency in athletes using a bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft. A two-year follow up study. Int Orthop. 1995;19:1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00184906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keays SL, Bullock-Saxton J, Keays AC. Strength and function before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:174–183. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200004000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keays SL, Bullock-Saxton J, Keays AC, Newcombe P. Muscle strength and function before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using semitendonosus and gracilis. Knee. 2001;8:229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(01)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keays SL, Bullock-Saxton JE, Newcombe P, Keays AC. The relationship between knee strength and functional stability before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:231–237. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00160-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:364–380. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee DY, Karim SA, Chang HC. Return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction - a review of patients with minimum 5-year follow-up. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewek M, Rudolph K, Axe M, Snyder-Mackler L. The effect of insufficient quadriceps strength on gait after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2002;17:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(01)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, Roos H. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3145–3152. doi: 10.1002/art.20589. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maeda A, Shino K, Horibe S, Nakata K, Buccafusca G. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with multistranded autogenous semitendinosus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:504–509. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majewski M, Susanne H, Klaus S. Epidemiology of athletic knee injuries: A 10-year study. Knee. 2006;13:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manal TJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation: a criterion-based rehabilitation progression. Oper Tech Orthop. 1996;6:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcacci M, Zaffagnini S, Iacono F, et al. Intra-and extra-articular anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction utilizing autogeneous semitendinosus and gracilis tendons: 5-year clinical results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:2–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-002-0323-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00167-002-0323-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marx RG, Jones EC, Allen AA, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of four knee outcome scales for athletic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1459–1469. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marx RG, Jones EC, Angel M, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Beliefs and attitudes of members of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons regarding the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:762–770. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meszler D, Manal TJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Rehabilitation after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Practice guidelines and procedure-modified, criterion-based progression. Oper Tech Orthop. 2005;6:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moksnes H, Risberg MA. Performance-based functional evaluation of non-operative and operative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00816.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. Individuals with an anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee classified as noncopers may be candidates for nonsurgical rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38:586–595. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2008.2750. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2008.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moller E, Forssblad M, Hansson L, Wange P, Weidenhielm L. Bracing versus nonbracing in rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:102–108. doi: 10.1007/s001670000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myer GD, Paterno MV, Ford KR, Quatman CE, Hewett TE. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: criteria-based progression through the return-to-sport phase. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:385–402. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2222. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2006.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myklebust G, Bahr R. Return to play guidelines after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:127–131. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.010900. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2004.010900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakayama Y, Shirai Y, Narita T, Mori A, Kobayashi K. Knee functions and a return to sports activity in competitive athletes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Nippon Med Sch. 2000;67:172–176. doi: 10.1272/jnms.67.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noyes FR, Barber SD, Mangine RE. Abnormal lower limb symmetry determined by function hop tests after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:513–518. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noyes FR, Berrios-Torres S, Barber-Westin SD, Heckmann TP. Prevention of permanent arthrofibrosis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction alone or combined with associated procedures: a prospective study in 443 knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:196–206. doi: 10.1007/s001670000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noyes FR, Matthews DS, Mooar PA, Grood ES. The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee. Part II: the results of rehabilitation, activity modification, and counseling on functional disability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:163–174. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198365020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noyes FR, Mooar PA, Matthews DS, Butler DL. The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee. Part I: the long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:154–162. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198365020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson RK, Shelton WR, Bomboy AL. Allograft versus autograft patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:9–13. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.19965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pinczewski LA, Deehan DJ, Salmon LJ, Russell VJ, Clingeleffer A. A five-year comparison of patellar tendon versus four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:523–536. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300041201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reid A, Birmingham TB, Stratford PW, Alcock GK, Giffin JR. Hop testing provides a reliable and valid outcome measure during rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther. 2007;87:337–349. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060143. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Risberg MA, Holm I, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L. Neuromuscular training versus strength training during first 6 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87:737–750. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060041. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20060041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudolph KS, Axe MJ, Buchanan TS, Scholz JP, Snyder-Mackler L. Dynamic stability in the anterior cruciate ligament deficient knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:62–71. doi: 10.1007/s001670000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rudolph KS, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Dynamic stability after ACL injury: who can hop? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:262–269. doi: 10.1007/s001670000130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rudolph KS, Eastlack ME, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. 1998 Basmajian Student Award Paper: Movement patterns after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a comparison of patients who compensate well for the injury and those who require operative stabilization. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 1998;8:349–362. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(97)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudolph KS, Snyder-Mackler L. Effect of dynamic stability on a step task in ACL deficient individuals. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2004;14:565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2004.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scranton PE, Jr, Bagenstose JE, Lantz BA, Friedman MJ, Khalfayan EE, Auld MK. Quadruple hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a multicenter study. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:715–724. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.35262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shelbourne KD, Klotz C. What I have learned about the ACL: utilizing a progressive rehabilitation scheme to achieve total knee symmetry after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sci. 2006;11:318–325. doi: 10.1007/s00776-006-1007-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00776-006-1007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shelbourne KD, Nitz P. Accelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1992;15:256–264. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1992.15.6.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith FW, Rosenlund EA, Aune AK, MacLean JA, Hillis SW. Subjective functional assessments and the return to competitive sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:279–284. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2002.001982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snyder-Mackler L, De Luca PF, Williams PR, Eastlack ME, Bartolozzi AR., 3rd Reflex inhibition of the quadriceps femoris muscle after injury or reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:555–560. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199404000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Snyder-Mackler L, Delitto A, Bailey SL, Stralka SW. Strength of the quadriceps femoris muscle and functional recovery after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of electrical stimulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1166–1173. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snyder-Mackler L, Delitto A, Stralka SW, Bailey SL. Use of electrical stimulation to enhance recovery of quadriceps femoris muscle force production in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther. 1994;74:901–907. doi: 10.1093/ptj/74.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Snyder-Mackler L, Ladin Z, Schepsis AA, Young JC. Electrical stimulation of the thigh muscles after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Effects of electrically elicited contraction of the quadriceps femoris and hamstring muscles on gait and on strength of the thigh muscles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1025–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soon M, Neo CP, Mitra AK, Tay BK. Morbidity following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using hamstring autograft. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Porat A, Roos EM, Roos H. High prevalence of osteoarthritis 14 years after an anterior cruciate ligament tear in male soccer players: a study of radiographic and patient relevant outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:269–273. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.008136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner M, Kaab MJ, Schallock J, Haas NP, Weiler A. Hamstring tendon versus patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using biodegradable interference fit fixation: a prospective matched-group analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1327–1336. doi: 10.1177/0363546504273488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0363546504273488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Webster KE, Feller JA, Hameister KA. Bone tunnel enlargement following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a randomised comparison of hamstring and patellar tendon grafts with 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:86–91. doi: 10.1007/s001670100191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilk KE, Arrigo C, Andrews JR, Clancy WG. Rehabilitation After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in the Female Athlete. J Athl Train. 1999;34:177–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]