Abstract

Healthcare systems worldwide face a wide range of challenges, including demographic change, rising drug and medical technology costs, and persistent and widening health inequalities both within and between countries. Simultaneously, issues such as professional silos, static medical curricula, and perceptions of “information overload” have made it difficult for medical training and continued professional development (CPD) to adapt to the changing needs of healthcare professionals in increasingly patient-centered, collaborative, and/or remote delivery contexts. In response to these challenges, increasing numbers of medical education and CPD programs have adopted e-learning approaches, which have been shown to provide flexible, low-cost, user-centered, and easily updated learning. The effectiveness of e-learning varies from context to context, however, and has also been shown to make considerable demands on users' motivation and “digital literacy” and on providing institutions. Consequently, there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness of e-learning in healthcare as part of ongoing quality improvement efforts. This article outlines the key issues for developing successful models for analyzing e-health learning.

Key words: e-health, distance learning, information management

Introduction

Healthcare systems worldwide face a range of challenges in the 21st Century:

• Global health trends reveal substantial progress in terms of indicators such as life expectancy over the past 50 years, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, yet studies also attest to persistent inequalities in life expectancy within and between countries,1 while aging and increasingly obese populations present new challenges to healthcare systems in developed and developing countries.2,3

• Significant improvements in tackling infectious diseases have been made, with mortality rates for all main infectious diseases expected to decline between now and 2030, yet chronic noncommunicable diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, and mental illness are becoming increasingly significant in the global health context, with higher mortality rates expected as populations age.3

• In 2008 it was estimated that none of the health-related Millennium Development Goals would be met by 2015 in sub-Saharan Africa, and with variable success elsewhere.1

• Healthcare delivery costs have risen steeply in recent years, driven by rises in the costs of medical technology, education, and drugs and by the demands of aging populations, yet the World Health Organization recently estimated that between 20% and 40% of all health spending is wasted through inefficiency and pointed out that countries with similar levels of health spending achieve strikingly different health outcomes.4

In response to the challenges of aging populations and changing disease burdens, many healthcare systems across the world have initiated policy reforms aimed at reducing inefficiencies and health inequalities. Healthcare policy scholars have increasingly recognized the significance of non-state actors such as international and non-governmental organizations in generating global networks that facilitate coordinated policymaking in line with international objectives (such as the aforementioned United Nations Millennium Development Goals).5 Partly facilitated by such networks, many health system reforms since the 1980s have adopted neoliberal new public management (NPM) approaches, characterized by attempts to increase service efficiency and accountability through heightened managerial oversight.6 More recently, “post-NPM” approaches have introduced notions of quality, effectiveness, patient-centered care, interprofessional collaboration, and clinician-directed budgeting alongside NPM doctrines of efficiency and accountability, although critics suggest that these policy programs remain underfunded and are undermined by continuing NPM efficiency and control imperatives.6,7

The range and severity of global healthcare challenges combined with the scope and breadth of healthcare reforms generate considerable difficulties for medical education and continued professional development (CPD). A recent study outlines these difficulties:

In many countries, professionals are encountering more socially diverse patients with chronic conditions, who are more proactive in their health-seeking behaviour. Patient management requires coordinated care across time and space, demanding unprecedented teamwork. Professionals have to integrate the explosive growth of knowledge and technologies while grappling with expanding functions—super-specialisation, prevention, and complex care management in many sites, including different types of facilities alongside home-based and community-based care.7(p.1926)

The same study identified eight key deficiencies: fragmented and outdated curricula; mismatch of competencies to patient and population needs; poor teamwork; persistent gender stratification of professional status; narrow technical focus without broader contextual understanding; episodic encounters rather than continuous care; predominant hospital orientation at the expense of primary care; quantitative and qualitative imbalances in the professional labor market; and weak leadership to improve health system performance.7 These difficulties arise against a changing educational background in which the emphasis has shifted from expert-led “teaching” to user-led “learning” and from process-focused curricula to competency-based learning,8 and within a clinical environment characterized by high levels of “information overload.”9 Attempts to address educational challenges have encountered obstacles including underfunding, the necessary complexity of educational reforms, and professional “tribalism” or “the tendency of the various professions to act in isolation from or even in competition with each other.”7(p.1923) These challenges have been particularly severe in developing world contexts owing to severe resource scarcity, the proliferation of unqualified health workers and providers without credentials, and short-term healthcare policy driven by external aid donor targets. Consequently, renewed efforts to reform medical education and CPD continue to be necessary in a wide range of contexts and for a wide range of workforce sectors.

e-Learning in Health

E-learning has potential to address this need through the dissemination of flexible and adaptable medical educational packages. Defined as the delivery of training or CPD material via electronic media (including Internet, CD-ROM, DVD, smartphones, and other media),10 e-learning has become an increasingly significant aspect of healthcare education programs since the 1990s,11,12 in line with the growth of “e-health” more generally.13 For the purposes of this work e-learning includes any form of training for lay persons, trainees, or health professionals.

E-health (as distinct from e-learning) refers to any Web-based program with a visible relationship to health. This could be symptom recognition tools for public use (e.g., WebMD, NHSDirect), electronic database management for national health systems, public health data for general use, online records or documents (e.g., e-prescriptions), learning programs, therapeutic programs (e.g., computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy), or research tools. E-learning provides an opportunity to develop and learn from major e-health initiatives and promote innovation in knowledge and practice to a global audience.

E-learning programs can be classified along several different axes (as seen in Table 1). These characteristics yield differing advantages and disadvantages. For example, asynchronous learning is more flexible than synchronous learning but typically allows for less interactivity and engagement between fellow learners. Similar issues apply to geographically co-located versus remote learning and individual versus collaborative learning. Electronic-only learning, likewise, is easier to carry out for individual learners, but blended learning is widely considered to provide a more positive and interactive learning experience because it retains the benefits of traditional face-to-face instruction and engagement while capturing some of the benefits of electronic-only learning (i.e., in the electronic components of the blended course).10

Table 1.

Dimensions of e-Learning Programs

| DIMENSION, ATTRIBUTE | MEANING | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronicity | ||

| Asynchronous | Content delivery occurs at different time than receipt by student. | Lectured module delivered via e-mail link or similar |

| Synchronous | Content delivery occurs at the same time as receipt by student. | Lecture delivery via Webcast |

| Location | ||

| Same place | Students use an application at the same physical location as other students and/or the instructor. | Using a group support system to solve a problem in a classroom |

| Distributed | Students use an application at various physical locations, separate from other students and the instructor. | Using group support system to solve a problem from distributed locations |

| Independence | ||

| Individual | Students work independently from one another to complete learning tasks. | Students complete e-learning modules autonomously. |

| Collaborative | Students work collaboratively with one another to complete learning tasks. | Students participate in discussion forums to share ideas. |

| Mode | ||

| Electronic-only | All content is delivered via technology. There is no face-to-face component. | An electronically enabled e-learning course |

| Blended | E-learning is used to supplement traditional classroom learning (and vice versa). | In-class lectures are enhanced with hands-on computer exercises and/or pre-class exercises. |

Adapted from Omar et al.14

Proponents8,10,14–16 of e-learning have advanced several ostensible benefits deriving from both electronic-only and blended forms of e-learning, including the following:

1. Time and location flexibility and accessibility

2. Lower training costs and time commitment

3. Self-directed and self-paced learning by enabling learner-centered activities

4. Collaborative learning environment

5. Builds universal communities

6. Standardized course delivery

7. Allows unlimited access to e-learning materials

8. Private access to learning

9. Just-in-time learning

10. Workforce training monitoring

11. Allows knowledge to be updated and maintained in a more timely and efficient manner

The Evidence

Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the claims for e-learning in various contexts, including healthcare education and CPD. Findings have generated mixed results but often lead to the conclusion that most e-learning programs are far more effective than no training intervention and are as effective as traditional teaching methods, although positive comparative effects are heterogeneous and frequently small.8,12,17 (The results from the meta-analysis of Cook et al.12 of Internet-based learning in the health professions were as follows: pooled effect size in comparison with no intervention favored Internet-based interventions and was 1.00 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.90–1.10; p<0.001; n=126 studies] for knowledge outcomes, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.49–1.20; p<0.001; n=16] for skills, and 0.82 [95% CI, 0.63–1.02; p<0.001; n=32] for learner behaviors and patient effects. Compared with non-Internet formats, the pooled effect sizes [positive numbers favoring Internet] were 0.10 [95% CI, −0.12 to 0.32; p=0.37; n=43] for satisfaction, 0.12 [95% CI, 0.003–0.24; p=0.045; n=63] for knowledge, 0.09 [95% CI, −0.26 to 0.44; p=0.61; n=12] for skills, and 0.51 [95% CI, −0.24 to 1.25; p=0.18; n=6] for behaviors or patient effect.) Positive aspects of user experience included perceptions of increased convenience, user-tailored learning, and faster skill development8,16 and highlighted the fit between e-learning (especially in blended formats) and the broad shift toward competency-based medical curricula.18 Studies in nonmedical contexts have also shown that e-learning can result in cost savings of up to 50% over traditional training, owing to reduced instructor training time, travel and labor costs, and institutional infrastructure and the possibility of expanding programs with new technologies.8

In contrast to these (tentatively) positive conclusions, there are a small number of studies suggesting that some pure e-learning programs (i.e., non-blended approaches) have worse outcomes than traditional learning because of factors such as lack of face-to-face interaction, high dropout rates, lack of accountability of learners or instructors, and lack of hands-on activities.10 Non–user-friendly interfaces, accessibility problems, and lack of “digital literacy” are challenges to user satisfaction.19 Many blended programs also fail to achieve desired outcomes owing to factors such as inappropriate technology, mismatched instructor characteristics, and a lack of cultural, organizational, and information technology support.10 Furthermore, some critics have suggested that e-learning programs struggle to convey “tacit,” or experiential, knowledge traditionally considered essential to medical apprentice-style learning, as opposed to “explicit” knowledge, or easily codifiable information, which is more easily conveyed using electronic means.9 (It should be noted, however, that some scholars believe e-learning to be capable of delivering tacit knowledge when a blended and interactive approach is adopted, and especially when “Web 2.0” features, such as interactive user groups, blogs, “folksonomies,” and “mashups,” are deployed as part of the e-learning experience [see Boulos and Wheelert.20]).

It should not be assumed that everyone benefits from e-learning. Recent work on learning theory and student preferences demonstrates very real limits. A major report from Canada21 outlines critical issues faced by online components of university education, as many students reported negative opinions of e-learning resources. Although this is in the context of full-time undergraduate study and does not singularly address actual online teaching, it still highlights likely resistance from those less comfortable with the online approach. Whether reluctance to participate in such programs should be addressed or conceded is a matter for another debate.

Current

In two systematic reviews, Cook et al.12,22 identified a large number of studies investigating e-learning programs in health. These reviewed the impact and benefits of e-learning versus traditional classroom teaching or similar comparisons, including areas such as convenience, accessibility, and time. Ruiz et al.8 outlined the impact that e-learning can potentially have within medical education. Although their study focused largely on training within medical schools and less on continuing education or general levels of health education, the possibilities are extensive. The article even goes as far as encouraging career advancement at the academic levels for those who make best use of e-learning.

Costs

It is surprising that although online education methods may have a benefit in relation to time or potential audience, cost-effectiveness has gone essentially unreported, with the limited exception of private business.23 More information is needed to develop a robust understanding of potential gains. Also, the introduction of e-learning can represent an intrusion into the personal time and resources of a trainee in addition to institutional costs.

Security and Reliability

The nature of the Internet provides no global safeguards for reliability of material or the protection of data against misuse. Countless controls may exist for protection against a variety of dangers, but these are largely symptom-based and cannot always be applied in all situations. For example, an online store for health supplies may be able to sell pharmaceuticals to a region where it has been outlawed if its physical base is outside local jurisdiction. Many public information outlets are without review, meaning accuracy should never be assumed from unknown sources. Although these are but two of many possible issues, there are opportunities to establish online locations for secure, trustworthy health information. These issues served as a major point in the prospective review of e-health by Wyatt and Franklin.24 Although there are many reasons why e-health generally should grow, it is not without consequence, and safety and financial benefit should not be assumed.

Critical Success Factors for e-Learning

On the basis of the evidence, scholars have identified several critical success factors (CSFs) for e-learning programs. These include:

• Institutional characteristics: organizational support (e.g., time allocated for training/CPD and incentives for learning); cultural support (i.e., a supportive learning environment); and information technology support (including both technical infrastructure and learner information technology assistance); also organizational readiness for e-learning10,25

• Instructor characteristics: motivation; positive attitudes toward e-learning and blended approaches; positive attitude toward learners; high levels of technical and educational competency

• Learner characteristics: motivation; positive attitudes toward e-learning; digital literacy

• E-learning program characteristics: blended programs, incorporating a mix of synchronous and asynchronous and co-located and remote learning, are most likely to balance face-to-face learning benefits with e-learning flexibility and user-centered learning.10,15,26–28

A healthcare context requires additional CSFs for e-learning. These include constant updating of course content to keep clinicians informed about latest research and practice findings, monitoring of workforce learning and CPD levels to ensure workforce awareness of the latest clinical guidance, and continual development of e-learning and the adoption of new (Web 2.0-based) technologies in order to ensure the greatest possible alignment of training with competency-based, user-focused, and tacit knowledge-oriented delivery models.20

Standardized Frameworks

Surviving Reform

E-learning is particularly relevant at present because of major health service reforms. It is evident in the OECD Observer's 2010 special issue on global health costs that many countries, particularly in North America and across Europe, face imminent changes to their medical systems.29 Regardless of location or approach to health system changes, a shift is expected in how care programs are managed, with doctors being increasingly responsible for medical administration. This presumably requires increased training around innovation and redesign, for which effective dissemination of information is key. Furthermore, it is necessary for health systems to report on the impact of changes and resulting benefits at many levels because the global health community needs consolidated information about new knowledge and best practice.30

There is a need for each new level of e-health to have standardized frameworks to ensure safeguarding and healthy competition. In Australia, the National e-Health Transition Authority has led on moves to assess tools for e-health to establish standards. Although the Authority recognizes the vast potential for advancing knowledge in health globally and it may be a leader in undertaking such a major initiative, the focus of its work is on integrating national data. Regardless, it serves as a promising sign for effective and reliable health innovation.

Aside from education, other elements of health systems have already made strides toward Internet-based operations. For example, e-prescriptions are already being subjected to frameworks developed and reviewed by the American Medical Association. This work is currently up for judicial review by the American government, further demonstrating the imminent use of online care. Various Canadian offices (e.g., Health Canada, Office for Health and Safety) have also taken steps to oversee and join national training programs (although it should be noted that there have been negative reports on the acceptability of e-learning among Canadian students [see Istepanian and Zhang31]). Unfortunately, the United Kingdom's attempt to consolidate information via the National Health Service's Connecting for Health, an online database collaboration, failed to be realized.

Such advances offer the opportunity to explore use and standardization in many areas of health and care. The innovative steps taken by the Australian, Canadian, and American programs exemplify how progress should look: programs should be developed with global potential but begin within the jurisdiction (whether locally or nationally mandated) of a given health and care context. In other words, e-health frameworks should be applicable universally but adaptable to local laws. To better aid this process, relevant international organizations should produce qualified models to evaluate the efficacy and safety of innovative health programs.

Much like the lack information on cost-effectiveness, the evaluation of training programs for health professions raises concern. This is particularly noted in light of recent expansions to make use of mobile technologies in training.32 Although there are a considerable number of elements (e.g. services, applications, access) to m-health,31 perhaps the most critical in establishing the efficacy of such developments relates to health-related learning at a population level, which was indicated in a recent WHO report.33

The Need for Robust Evaluation

E-learning programs in healthcare, as in other contexts, exhibit a variety of design characteristics, target workforces, levels of support, and levels of success in meeting learning and CPD outcomes; also, the changing global healthcare context provides its own challenges, which means any innovations in training have potential to integrate with new educational paradigms. The benefits of medical e-learning cannot be taken for granted, and programs must be evaluated within their specific contexts.

A key barrier to our understanding of the impact of Internet-based training for health professionals is the limited scope of existing evaluations. It is a concern that in current e-learning for health the scope of evaluation is typically limited to user enjoyment and satisfaction. Whether or not students enjoyed or felt they learned from such programs is not a sufficient basis on which to recommend adoption at even a local level, and certainly not in resource-limited regions. Programs need to be evaluated at a range of levels from efficacy through to implementation and dissemination.

Turner et al.34 implied and Ruiz et al.8 stated outright that the evaluation of educational programs in many ways requires more investment than development of the content. This is especially relevant during the piloting phase, when process factors as well as outcomes need to be evaluated in order to plan for future implementation. A range of factors may be considered. For instance, Morey et al.35 demonstrated that effective evaluation must involve evaluation at a variety of levels, including multiple stakeholders and learning outcomes; Turner et al.34 demonstrated the impact on stakeholders and also reviewed obstacles to program implementation. Measuring efficacy of a clinical program for medical trainees centers primarily on whether students have understood the skill and made use of it and on how the process compares with traditional learning.

Health education almost always has a social element, and it is important to evaluate more than just learning and skills to fully understand the benefits of a program. For example, Morey et al.35 implemented a training program to improve emergency room teamwork. As well as evaluating knowledge acquisition, they sought feedback from team members about their colleagues to determine how teamwork had improved. Recognizing the value of patient input, they assessed measures of patient satisfaction, thus incorporating elements of co-creating health and patient-centered medicine.

Although a program may be effective at supporting trainees to develop the necessary skills and attitudes, it is also vital that trainees are able to apply these in their day-to-day work, and so potential and known barriers to implementation must be included in the evaluation.34 Barriers can then be addressed before participation in the program. For example, Turner et al.34 found that although care home staff were satisfied with new approaches to palliative care, they saw no reason to change their practice because district nurses typically disregarded their input. In such a situation, it should not be left to the participants to put demands on their bosses, but to those sponsoring the training to make sure effective training may be put to use.

With improved evaluation and more input from stakeholders, particularly in health programs, e-learning will develop more effectively.

Model for Evaluating Learning in e-Health

Theoretical models of e-learning are still very much in the early stages.36 This is of critical importance in developing tools as not enough is fully understood about how people learn through online study. In order to promote better use and understanding of e-learning in health, an informed and widely agreed model for evaluation must be in place.

The latter part of this report sets out an evaluation model that can be applied in a variety of contexts worldwide. It is not necessarily the case that evaluations of e-learning programs should incorporate all of the elements proposed in this model to be considered robust, particularly if the program has an already established outcome, but we recommend that the full range of elements be considered.

The model is proposed as a minimum standard for evaluation, with some additional levels not necessarily always for analysis. There are factors that may be relevant for some but not all evaluations, for instance, traditional testing methods, staffing for information and communication technology elements, or unique audit types. Where this information is available, inclusion is encouraged.

The model proposed here is not entirely novel and is based on existing evaluation models in education.37 It bears similarities to published evaluation guides but is adapted to encompass the impact on stakeholders beyond the trainees and their self-reported course impressions. Additionally, it extends to decision-making criteria for parties not involved in the initial development as well as external considerations (namely, obstacles) relating to practical implementation.

The novel proposition made here is that such an evaluation model needs to be adopted and promoted by major health organizations as a standard for acceptability of Web-based programs they accredit or implement. We propose the model as a step toward a global standard for e-learning in health that is applicable to all levels and types of organization. There is an urgent need to identify which programs are effective and reliable and what factors lead to positive and negative outcomes. Without a clear assessment of benefits and the capacity for systematic review, the field will continue to yield incomparable, anecdotal, and/or otherwise insufficient evidence of potentially innovative training.

Applicability

The model can be applied to any program in e-learning in health for lay people, patients, or professionals. It is important to note that e-learning is not only meant for those employed in health. Even in the early days of health information and communication technology, online resources enjoy widespread use; thus evaluation must go beyond classroom-style assessment and be applicable for lay people.

Measures

For the measures in the model being proposed, complex elements must be considered. Individuals vary in their openness to e-learning, meaning a combination of evaluation methods is required. Although previous e-learning programs have sometimes relied solely on simple measures (i.e., how enjoyable was the course, or how much did you learn from it), self-report must be incorporated to relate to objective outcomes. Without this level of data, it will be difficult to assess whether learning or application from the program has been determined by participants' general experience or perceived need to provide particular feedback. Self-report measures must have demonstrated validity and reliability in addressing what factors influenced the experience, for both description and adaptation. Collectively, this should assist in developing e-learning theory by acknowledging that not everyone is comfortable with it at a level that may be addressed. Although it does not replace other measures in the first instance, nor should it be overemphasized as the primary element in whether to implement a new program, it must be included.

Comparing e-Learning with Other Methods

Comparison with other methods will establish the relative value of e-learning compared to existing methods. If e-learning is intended to aid, subsidize, or replace an existing program, then a comparative evaluation must be made between the standard training and the e-learning program. There must be a comparison of impacts and outcomes at all levels, and evaluation measures should not be limited solely to participant assessment. This also applies to more complex settings, for instance, determining access to health promotion through e-learning where the same information could also be provided through clinics, schools, or other routes.

Standards

Standards are critical to global health and are necessary in developing programs for potentially universal use; they allow for collaborative, centralized storage and global accessibility of e-learning programs. In this way, pedagogically sound programs can be made readily available. This ambition is a large step from the current situation, but should at least be considered by those developing such programs. Much like the World Health Organization's call for better evidence on screening in the European Union,38 empirical evidence of the impact of e-learning programs is needed before policy-level decisions should be made on how or where they may be used. It is important that comprehensive evaluation is supported by major health organizations that promote the use of Web-based training materials.

Proposed Model

It is important to re-emphasize the value of investing in evaluation during the development and piloting of a program. This is particularly the case where the value of the program content is already established, and the key need is to assess how the content can be relayed via e-learning. There is an obligation for those developing or recommending a particular program to provide robust, empirical evidence on the outcomes of their approach. Once established, further assessment is left to those who adopt or otherwise make use of the information.

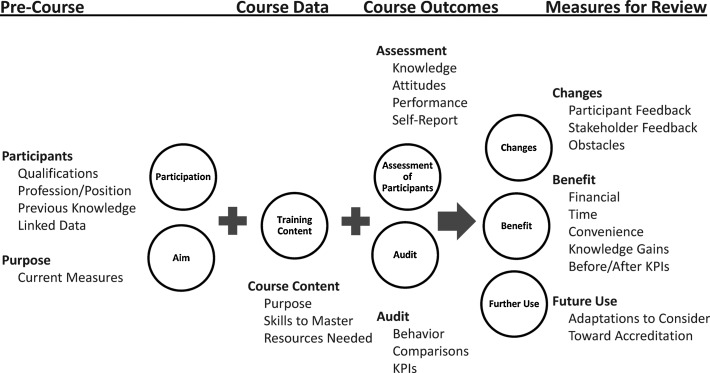

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the model.

Fig. 1.

A model for evaluation of e-learning programs in health and care. KPIs, key performance indicators.

The vignette in Sidebar 1 illustrates how effective evaluation is important even for training in a simple procedure. In this instance, the emphasis is on quantitative measures, as this will provide far better data for models and comparisons in future use. Some qualitative methods are included to provide context-specific information.

Sidebar 1. Example of a Program on Clinical Record Forms and Evaluation.

1. Purpose. A local health authority has developed a better document for patient records that provides extensive and rapidly input data for wider use. The form has been introduced because local offices need better individual information for various research, budgeting, and public health programs, but the initial training day was poorly attended and received.

2. Intake/participants. The online training will target any clinical staff potentially responsible for recordkeeping, particularly doctors, nurses, and administrative staff.

3. Purpose. They will be trained on how to complete the forms, because previous attempts to integrate them have resulted in incomplete or otherwise insufficient use.

4. Knowledge. Trainees will be expected to learn principles from public health and epidemiology on why seemingly irrelevant or excessive questioning is needed at all opportunities.

5. Resources. As clinics have already been provided the documents, they simply need one at hand when completing the program.

6. Attitude. Participants should learn the basis of the form for personal benefit and explaining to potentially unwilling patients, and they will be gauged on these when beginning the training session.

7. Behavior/attitude. They should be willing to comprehensively complete them for all patient visits—no matter the frequency—as changes can occur at any time and are highly relevant.

8. Knowledge/performance. Potentially subjective or alternate responses should be clearly described using provided terminology (e.g., unknown histories or treatments/illnesses not included in the form), in which trainees must demonstrate satisfactory performance.

9. Time. Clinic managers will require staff to complete the 1-h training at their leisure within working hours but within a 3-week frame before they will be held out from work until done.

10. Assessment. Some immediate measures will be taken from participants, including basic multiple choice items about the instrument, opinions toward using the form, and attitude toward the program. Using a timed system, participants will receive an automated e-mail exactly 2 weeks after clicking the “complete” button. This e-mail will include yes/no items on their opinion of the document, questions about the reasons for its use, and self-report measures about the course and if they have made use of the form. Participants will have 1 week to open the assessment, which must be completed in a single sitting within 12 min of being accessed. The measurement will allow trainees to say if they now value the form, accept its purpose, have obstacles (such as time with patients or excessive paperwork), or prefer changes in the course, among other topics.

11. Audit. The local authority will review hospital records of the form's use up to the day before the date of the first online completion. Three months after the final examination, an equivalent review will be performed. Course facilitators will then be responsible for a review of information and communication technology (and other) costs, particularly in comparison with what other options would have cost and those of the original/failed training.

12. Benefit. They will report the findings of the self-report, performance, and attitude items concurrently with the audited behavior results. Additionally, they will query patients about their feelings of the extensive questioning as well as administrative staff responsible for managing data not trained. This will be viewed in direct reference to the intended outputs of the program.

13. Changes. Some qualitative feedback will be solicited in free-text portions of the assessment, which will be included where appropriate.

14. Future use. Ultimately, the facilitators will recommend whether or not the training is requisite for all staff and how to improve future training, should it qualify for further use. Once established, the training program may be recommended to larger clinical audiences, with broader offices determining if they should implement identical programs into their mandatory training.

Benefits

Outcomes measured should enable evaluators to identify benefits of the program and any amendments necessary to the program and allow the development of models for replication and roll out.

The benefits assessed should reflect the aims of the program. These commonly include financial savings, time/location convenience, or ability to reach a wider audience, among other indicators. For example, financial benefits may save a training program vulnerable to budget cuts; individual convenience means a program is more practical, which may therefore lead to more training opportunities for staff.

Intake

A shortcoming of many evaluations of e-learning is the absence of baseline data and a reliance on self-report of before/after perceptions of knowledge. Baseline recording of qualification, occupation (or area of study), and experience are critical. If the program is intended for a professional audience, then details of their expertise (e.g., wards, previous training) at baseline are essential for understanding the impact of the program and any resulting behavior changes.

Content

It is often assumed that the content of the training is already established and that key indicators exist for the knowledge or ability contained in the program—e-learning is not an acceptable medium for trialing new procedures or skillsets. Content may relate to procedure change, new tools (written or technical), regular staff development training, or a variety of other possible concepts.

Costs

The level of resources needed to realize the entire program should be evaluated to provide values for non–information and communication technology costs. This could include cost of trainee time or savings through avoidance of print materials but should present a comparator from a previous delivery method.

Assessment

The development of e-learning programs relies on good quality outcome assessment following a clear statement of the intended gains in competence.

Outcome measures should include knowledge, attitudes, and behavior to ascertain what students have learned. Individual programs should operationalize these in their particular context. For example, programs that focus on raising awareness will differ from those teaching new techniques to clinical staff. Objective measures should be included.

If performance measurement is necessary, then objective measures are recommended to enable replication, although it is conceivable some subjective (e.g., satisfaction with course) items may be included. Performance measures are important where e-learning may be used to replace or compare to another medium—comparing performance between two programs will identify if there is a difference in competence acquisition. It is possible that performance and knowledge measures will overlap as they are comparable concepts.

Objective self-report measures can provide information about improvements needed to the program or obstacles to implementation, for instance, perceptions of the format, content, or resources. Measurements should allow for replication (e.g., a Likert-type scale ranging from highly positive to highly negative scores). Other qualitative measures may serve in support, but such information may be context-specific and useful only for the original developers.

Audit

Trainees may have acquired the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but this does not guarantee that they will implement them following the program. Audit is a means of reviewing relevant outputs to establish if implementation has been effective. Audit results are necessary to justify spread and further uptake of the program.

In most cases, existing key performance indicators will determine the measurements to be audited. These could range from counts of information within hospital data to seeking feedback from stakeholders impacted by the program. It will be important to ascertain if stakeholder impact is the same when students learn online as opposed to in-person. Auditing is usually the most involved level of evaluation as it requires gathering of data beyond just course participants. Programs must demonstrate comprehensive evaluation. This should also extend to future improvements in the program based on participant feedback.

Where an audit is assessing behavior, then pre- and post-training behavior should be compared. If possible, objective measures of behavior should be included because self-reports of behavior may be unreliable. If it is not possible to measure actual behavior, then a measurable proxy should be identified.

Improvement

Amendments to the program are inevitable. Most e-learning studies will include or be entirely composed of a piloted course, and so recommendations for improvement are expected. Data may take the form of participant or stakeholder feedback, information technology reports, or undesirable results of the assessment/audit and contribute to understanding how the positive or negative results were achieved. Feedback should be sought from stakeholders other than participants, as they may have more insight into outcomes that were not effectively addressed in the training.

Barriers

External barriers (i.e., factors outside the program) to implementing learning must be evaluated. Students may acquire the intended knowledge, skills, and attitudes but face a variety of barriers—financial, social, bureaucratic, practical, even unintentional—which make application impossible. Evaluation of these barriers is the shared responsibility of e-learning facilitators and educators as a whole because impracticable skill training is a poor use of resources. Barriers must be included in a program review, particularly if future attempts to address the problem are to demonstrate objective improvement. Audiences reviewing this work must be aware of such issues.

Accreditation

If e-health programs continue to grow, it is a responsibility of those organizations supporting or implementing them to assess their efficacy and promote them globally. Whether or not this includes an official standard for accreditation is for future debate, but developing guidelines is important. Although it is not suggested that programs will meet a specified level of accreditation simply by fulfilling the criteria in this model, the model does provide a minimum standard and a starting point for discussion and dialogue.

Responsibility for e-Health

Progress

As e-health programs become more common, program coordinators will rely on key partners in health, ranging from clinical staff to community care. Among the key players are the research wings of healthcare. In the United Kingdom, for example, public health observatories have previously provided extensive health data for public and academic use. However, they currently face budget reductions, leading to fewer staff and diminished capacity. The major audit element described in this model relies on the ability to access data, particularly if a program has a social focus (for intervention effect in a population) or a specific/clinical scope (requires special clearance to protected information). A local public health observatory would have the potential capacity to support efficient and safely guarded analysis at this level so that e-health coordinators would not need to spend excessive time collecting data. The application of health information through any e-program is a direct example of public health in the information age; thus the support for necessary information must not be reduced. Public health observatories, along with strategic health organizations in research and training, are key sources of data for implementation into health policy and education.

As has been demonstrated with the discontinuation of Google Health and limited return from other corporate attempts, privatized public health data have not been effective at producing sustainable consolidation of e-health data. Unless there are better standards and safeguards on the provision of data and a reputable, centralized information bank in e-health, the same fate is likely for e-learning.

Limitations of the Model

This evaluation model does not acknowledge the language barrier likely to be faced by a locally developed course with aspirations for global use. For example, if the World Health Organization were to continue the push toward e-health programs and attempt to consolidate them via widely available sources, the presumption is that these would be available in the working languages of the United Nations. A better and more thorough approach to translation for use is needed.

An accreditation standard for online training is a desirable next step in e-health. This will require considerable peer review to ensure pedagogically viable courses.

The model does not describe how to structure the content or facilitation of e-learning, nor does it address methods of presenting information within the program. These are steps for future, more advanced models, which should draw on educational theory and research. Other areas that should eventually become part of the model include more specific direction on advanced assessment models or alternates to the measures suggested. Innovation may be useful in finding more subjective measures than suggested, although the objectivity has been dominant here for the point of direct comparison.

As was stated, the model perhaps explicitly applies to a direct training program but could easily be adapted to experiments in new Web sites providing public health information (presumably a trial of knowledge gains using the site versus common knowledge or alternative promotion).

Conclusions

Application of the Model

Considerable work has been done to date in e-health, and e-learning programs continue to be used. In order to extend the benefits from this work, interested organizations should work toward establishing a model such as the one proposed here as a standard for evaluating programs in a range of contexts. This includes e-health at the level of informational Web sites, specific e-learning for health professionals, or even service redesign, which has a demonstrable positive impact. Each of these is important in global health, and, given the opportunities offered by Internet as a medium for learning, such a model is valuable. The aim of the model is to provide a practical and adaptable framework to support the systematic development of high-quality evaluations to elicit valuable and important information for decision makers.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Frances Early and Prof. Robert Istepanian for invaluable input on the contents of this text. This work was supported by funds from the NIHR's Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Beaglehole R. Bonita R. Global public health: A scorecard. Lancet. 2008;372:1988–1996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James W. WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int J Obes. 2008;32:120–126. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler R. Population aging and health. BMJ. 1997;315:1082–1084. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson J. Ovseiko P. Global policy networks: The propagation of global health care financing reform since the 1980s. In: Lee K, editor; Buse K, editor; Fustukian S, editor. Health policy in a globalizing world. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 97–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diffenbach T. New public management in public sector organizations: The dark sides of managerialistic ‘enlightenment.’. Public Admin. 2009;87:892–909. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frenk J. Chen L. Bhutta Z. Cohen J. Crisp N. Evans T. Fineberg H. Garcia P. Ke Y. Kelley P. Kistnasamy B. Melies A. Naylor D. Pablos-Mendez A. Reddy S. Scrimshaw S. Sepulveda J. Serwadda D. Zurayk H. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz J. Mintzer M. Leipzig R. The impact of e-learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2006;81:207–212. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klass D. Will e-learning improve clinical judgement? BMJ. 2004;328:1147–1148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed H. Hybrid e-learning acceptance model: Learner perceptions. Decision Sci J Innov Educ. 2010;8:313–346. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Childs S. Blenkinsopp E. Hall A. Walton G. Effective e-learning for health professionals and students—Barriers and their solutions. A systematic review of the literature—Findings from the HeXL project. Health Inf Libraries J. 2005;22:20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-3327.2005.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook D. Levinson A. Garside S. Dupras D. Erwin P. Montori V. Internet-based learning in the health professions: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:1181–1196. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ball M. Lillis J. E-health: Transforming the physician/patient relationship. Int J Med Inform. 2001;61:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(00)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar A. Kalalu D. Alijani G. Management of innovative e-learning environments. Acad Educ Leadership J. 2011;15:37–64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nisar T. E-learning in public organizations. Public Personnel Manage. 2004;33:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harun MH. Integrating e-learning into the workplace. Internet Higher Educ. 2002;4:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappel J. Hayen R. Evaluating e-learning: A case study. J Comput Inf Syst. 2004;44:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell M. Learning differently: E-learning in nurse education. Nurs Manage. 2006;13:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson R. Stewart D. The influence of computer and Internet access on e-learning technology acceptance. Business Educ Digest. 2007;XVI(May):3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulos MNK. Wheelert S. The emerging Web 2.0 social software: An enabling suite of sociable technologies in health and health care education. Health Inf Libraries J. 2007;24:2–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers J. Usher A. Kaznowska E. The state of e-learning in Canadian universities, 2011: If students are digital natives, why don't they like e-learning? Toronto: Higher Education Strategy Associates; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook D. Levinson A. Garside S. Dupras D. Erwin P. Montori V. Instructional design variations in Internet-based learning for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2010;85:909–922. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d6c319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandars J. Cost-effective e-learning in medical education. In: Walsh K, editor. Cost effectiveness in medical education. Oxford, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing; 2010. pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wyatt J. Franklin C. eHealth and the future: Promise or peril? BMJ. 2005;331:1391–1393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7529.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreurs J. Gelan A. Sammourm G. E-learning readiness in organisations—Case healthcare. Int J Adv Corp Learn. 2009;2:34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Psikurich G. E-Learning: Fast, cheap, and good. Perform Improve. 2006;45:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy A. SMEs: How to make a successful transition from conventional training towards e-learning. Int J Adv Corp Learn. 2006;3:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu W. Hwang L-Y. The effectiveness of e-learning for blended courses in colleges: A multi-level empirical study. J Electron Business Manage. 2010;8:312–322. [Google Scholar]

- 29.A cure for health costs. OECD Observer. 2010(281):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dal Poz M. Modernizing health care: Reinventing professions, the state and the public. Global Public Health. 2010;5:105–107. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Istepanian RSH. Zhang YT. Guest editorial. Introduction to the special section: 4G Health—The long term evolution of m-Health. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2012;16:1–5. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2012.2183269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Istepanian RSH. Jovanov E. Zhang YT. Introduction to the special section on M-Health: Beyond seamless mobility for global wireless health-care connectivity. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2004;8:405–414. doi: 10.1109/titb.2004.840019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. mHealth: New horizon for health through mobile technologies. Global Observatory for e-Health Services. Vol. 3. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner M. Payne S. Froggatt K. All tooled up: An evaluation of end of life care tools in care homes in North Lancashire. End of Life Care. 2009;3:59. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morey J. Simon R. Jay G. Wears R. Salisbury M. Dukes K. Berns S. Error reduction and performance improvement in the Emergency Department through formal teamwork training: Evaluation results of the MedTeams Project. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1553–1581. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews R. Does e-learning require a new theory of learning? Some initial thoughts. Journal for Educational Research Online. www.j-e-r-o.com/index.php/jero/article/view/84/108. [Nov 9;2011 ]. www.j-e-r-o.com/index.php/jero/article/view/84/108

- 37.W.K. Kellogg Foundation logic model development guide. Battle Creek, MI: W.K. Kellogg Foundation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holland WW. Stewart S. Maseria C. World Health Organization. Screening in Europe. 2006. www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0007/108961/E88698.pdf. [Jun 30;2012 ]. www.euro.who.int/_data/assets/pdf_file/0007/108961/E88698.pdf