Summary

The uppermost thin layer on the surface of the skin, called the epidermis, is responsible for the barrier function of the skin. The epidermis has a multilayered structure in which each layer consists of keratinocytes (KCs) of different differentiation status. The integrity of KC differentiation is crucial for the function of skin and its loss causes or is accompanied by skin diseases. Intracellular and extracellular Ca2+ is known to play important roles in KC differentiation. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying Ca2+ regulation of KC differentiation are still largely unknown. Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is a major Ca2+ influx pathway in most non-excitable cells. SOCE is evoked in response to a fall in Ca2+ concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum. Two proteins have been identified as essential components of SOCE: STIM1, a Ca2+ sensor in the ER, and Orai1, a subunit of Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane. In this study, we analyzed the contribution of SOCE to KC growth and differentiation using RNAi knockdown of STIM1 and Orai1 in the human keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT. KC differentiation was induced by a switch in extracellular Ca2+ concentration from low (0.03 mM; undifferentiated KCs) to high (1.8 mM; differentiated KCs). This Ca2+ switch triggers phospholipase-C-mediated intracellular Ca2+ signals (Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ response), which would probably involve the activation of SOCE. Knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai1 strongly suppressed SOCE and almost completely abolished the Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses, resulting in impaired expression of keratin1, an early KC differentiation marker. Furthermore, loss of either STIM1 or Orai1 suppressed normal growth of HaCaT cells in low Ca2+ and inhibited the growth arrest in response to a Ca2+ switch. These results demonstrate that SOCE plays multiple crucial roles in KC differentiation and function.

Key words: Store-operated calcium entry, Calcium channels, Orai channels, Epidermal keratinocyte

Introduction

The skin functions as physical protection for the body from harmful pathogens, hazardous chemicals or dehydration. This barrier function of the skin is carried out by the outermost thin layer called epidermis. The epidermis is a multilayered structure composed primarily of cells termed keratinocytes. Each layer of the epidermis consists of keratinocytes in different differentiation status. While undifferentiated keratinocytes in the basal layer are highly proliferative, they exit the cell cycle and undergo differentiation upon migrating to upper layers. Therefore, the integrity of differentiation process of keratinocytes is critical for skin barrier function. Defects in this barrier function are known to cause many skin diseases (Proksch et al., 2008).

Many factors interact to induce KC differentiation including calcium (Ca2+), vitamin D, and cell to cell contact (Bikle, 2010; Dotto, 1999; Yuspa et al., 1988). It has been reported that there is a gradient of extracellular Ca2+ concentration in the epidermis from low in the basal layer to high in the stratum granulosum, the uppermost layer of epidermis (Pillai et al., 1993). Indeed, increases of extracellular Ca2+ concentration (Ca2+ switch) can induce KCs to exit the cell cycle and express several differentiation markers in isolated primary KCs in vitro (Pillai et al., 1990). Furthermore, low extracellular Ca2+ concentration is critical to maintain the highly proliferative nature of undifferentiated KCs. It has previously been shown that the Ca2+ switch is sensed by a Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaR) in the plasma membrane of KCs (Tu et al., 2004). CaR is a G-protein-coupled receptor coupled to Gq type alpha subunits, and thus activation of CaR leads to activation of the phospholipase C pathway (Hofer and Brown, 2003). CaR-mediated PLC signaling is initially mediated by PLCβ and subsequently by PLCγ (Xie and Bikle, 1999). Suppression of the intracellular Ca2+ increase with chelators, or suppression of PLCγ activity attenuate KC differentiation, suggesting that Ca2+ signaling is a key signaling pathway for Ca2+-switch-induced KC differentiation (Li et al., 1995). However, the exact molecular mechanism underlying Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ mobilization is largely unknown. Several Ca2+-permeable channels are suggested to be involved in Ca2+ signaling in Ca2+-switch-induced KC differentiation including transient receptor potential family channels (Beck et al., 2008; Cai et al., 2006; Müller et al., 2008).

Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is a major Ca2+ influx pathway in most non-excitable cells (Parekh and Putney, 2005). As its name suggests, SOCE is activated by depletion of Ca2+ stores in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). SOCE is known to be involved in cell proliferation and differentiation processes (Darbellay et al., 2009; Hwang and Putney, 2012; Johnstone et al., 2010). SOCE is mediated essentially by two classes of proteins, the STIM and Orai proteins (Feske et al., 2006; Liou et al., 2005; Roos et al., 2005; Vig et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006). STIM proteins (STIM1 and STIM2) are single transmembrane proteins expressed in ER membrane with an EF-hand motif in the N-terminus facing the ER lumen. This EF-hand motif functions as a sensor for stored Ca2+ content (Liou et al., 2005). Reduction of ER luminal Ca2+ induces STIM1 to oligomerize and translocate to ER–plasma membrane junction termed puncta in which Orai1, a pore-forming subunit of SOC channels, is activated apparently by direct interaction with STIM1 (Liou et al., 2007; Park et al., 2009). Although translocation and puncta formation of ectopically expressed STIM1 has been demonstrated in the HaCaT keratinocyte cell line (Ross et al., 2007), the role of endogenous STIM1 and Orai1 proteins in SOCE in KCs has not yet been investigated.

In this study, we analyzed the involvement of STIM1 and Orai1 in SOCE in HaCaT KCs and their importance for Ca2+-switch-induced KC differentiation. siRNA-mediated knockdown of STIM1 and Orai1 strongly suppressed SOCE in HaCaT cells. Interestingly, the suppression of SOCE impaired Ca2+ storage in undifferentiated cells. Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses were also abolished by the defect of SOCE, leading to a failure in the induced expression of keratin 1 mRNA, an early differentiation marker gene. Furthermore, STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown suppressed steady state proliferation of undifferentiated KCs and also inhibited Ca2+-switch-induced cell growth arrest. These results establish an important contribution of STIM1- and Orai1-mediated SOCE to Ca2+ homeostasis and commitment of KC differentiation.

Results

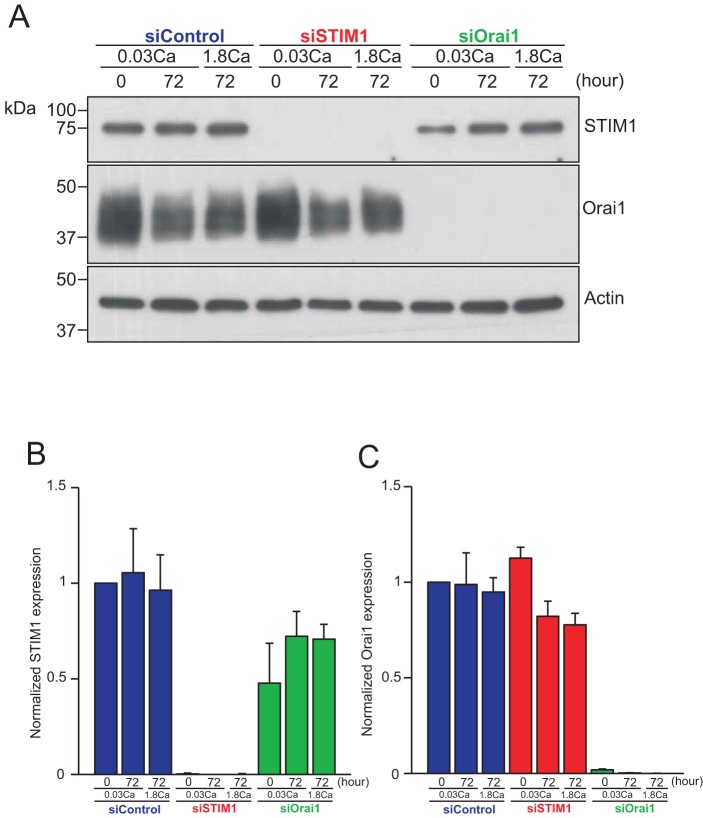

Induction of keratinocyte differentiation changes neither expression levels nor post-translational modification of STIM and Orai proteins

To analyze the involvement of SOCE in KC differentiation, we transfected HaCaT cells with siRNAs against either STIM1 or Orai1. KC differentiation was induced by Ca2+ switch. Cells were cultured routinely in 0.03 mM Ca2+-containing keratinocyte growth medium (KGM) to maintain undifferentiated status. Then the Ca2+ concentration was increased to 1.8 mM (Ca2+ switch) and cells were cultured up to 72 hours. Western blotting of both proteins was carried out to verify the efficiency of siRNA-mediated knockdown of STIM1 and Orai1 and to analyze whether their expression levels or posttranslational modification are changed during KC differentiation (Fig. 1). Both proteins were substantially reduced by siRNA, although some small amounts remained that could be seen on longer exposures of the gels (not shown). The mean level of STIM1 increased somewhat after 72 hours in culture. However, neither STIM1 nor Orai1 showed any difference in terms of their expression level and posttranslational modification during KC differentiation, that is when the 72 hour levels in 0.03 mM Ca2+ are compared to those in 1.8 mM Ca2+.

Fig. 1.

STIM1 and Orai1 protein expression during keratinocyte differentiation. (A) Western blotting showing STIM1 and Orai1 protein expression in siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells before and after Ca2+ switch. Note the broadening of the Orai1 band due to glycosylation, as shown by Fukushima et al. (Fukushima et al., 2012). The full lane westerns for both STIM1 and Orai1 are shown in supplementary material Fig. S1. (B,C) Densitometric analysis of STIM1 (B) or Orai1 (C) expression. Intensities of bands of STIM1 or Orai1 were normalized by those of actin. Relative expression to the sample at time 0 from siControl-transfected cells are shown. Data are means ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments.

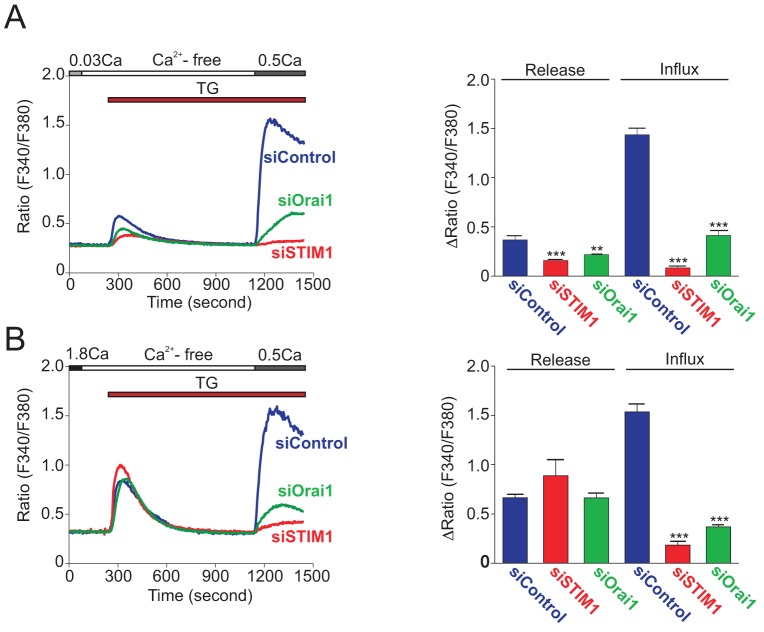

Knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai1 suppressed SOCE and Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current in HaCaT cells

Next, we analyzed the functional suppression of STIM1 and Orai1 by siRNAs using Ca2+ imaging (Fig. 2). After the depletion of intracellular ER stores by thapsigargin (TG), restoration of extracellular Ca2+ evoked large store-operated Ca2+ entry in HaCaT cells. To avoid saturation of the ratiometric fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-5F, we utilized 0.5 mM Ca2+-containing HBSS instead of 1.8 mM. Both STIM1 and Orai1 siRNAs strongly diminished TG-induced SOCE. STIM1 siRNA almost completely suppressed SOCE, while there was residual SOCE in Orai1 siRNA-transfected cells. The residual influx seen in the Orai1-knockdown cells likely results from the small remaining amount of Orai1. This influx was completely blocked by 2-aminoethyl borate (2APB) and by Synta 66 (supplementary material Fig. S2). Synta 66 has high specificity for Orai channels (Beech, 2012), and 2APB, at the concentration used here, does not block Orai2 or Orai3 (DeHaven et al., 2008). These results indicate that STIM1 and Orai1 constitute the major Ca2+ sensor and SOC channel in HaCaT cells.

Fig. 2.

Both STIM1 and Orai1 are indispensable for TG-induced SOCE in HaCaT cells. (A,B) Average time courses of TG-induced Ca2+ responses in siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells cultured in KGM-2 containing 0.03 mM Ca2+ (A) or 1.8 mM Ca2+ (B). Right panels showed peak [Ca2+] rises attributable to Ca2+ release and influx evoked by TG. Data are means ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

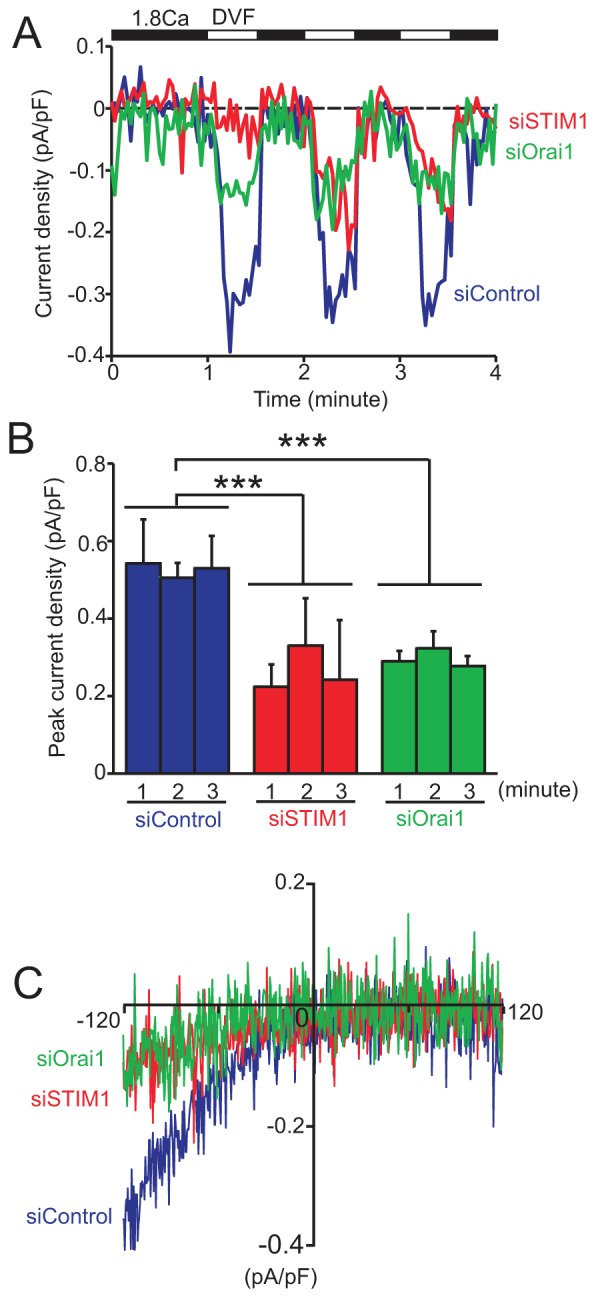

STIM1 and Orai1 constitute the prototypical SOC channel that gives rise to a Ca2+-selective Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current (ICRAC). We next analyzed the effect of STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown on ICRAC in HaCaT cells. Cells were dialyzed with 10 mM BAPTA and 20 µM inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate [Ins(1,4,5)P3] through the patch pipette to induce ICRAC. As observed in other many other cell types, endogenous ICRAC was too small to detect when using 1.8 mM Ca2+-containing extracellular solution (Fig. 3A). Therefore, we used a technique whereby a rapid change to a divalent-cation-free (DVF) extracellular solution transiently increases the size of an inward sodium ICRAC, due to removal of Ca2+ block (DeHaven et al., 2007). With this technique, we could readily record inwardly rectifying currents in siControl-transfected cells (Fig. 3A,C). Both STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown significantly reduced ICRAC in HaCaT KCs (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that STIM1 and Orai1 are the major constituents of endogenous CRAC channels which underlie the SOCE pathway in HaCaT KCs.

Fig. 3.

Both STIM1 and Orai1 are important for ICRAC in HaCaT. (A) Average time courses of ICRAC induced by intracellular dialysis of 20 µM Ins(1,4,5)P3 and 10 mM BAPTA. Switches of extracellular solution are indicated in the horizontal bar above the traces. (B) Peak inward current recorded at the holding of −120 mV. Data are means ± s.e.m.; siControl, n = 4; siSTIM1 and siOrai1, n = 3. ***P<0.001 (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test). (C) Representative current–voltage relationship of ICRAC in divalent-cation-free solution.

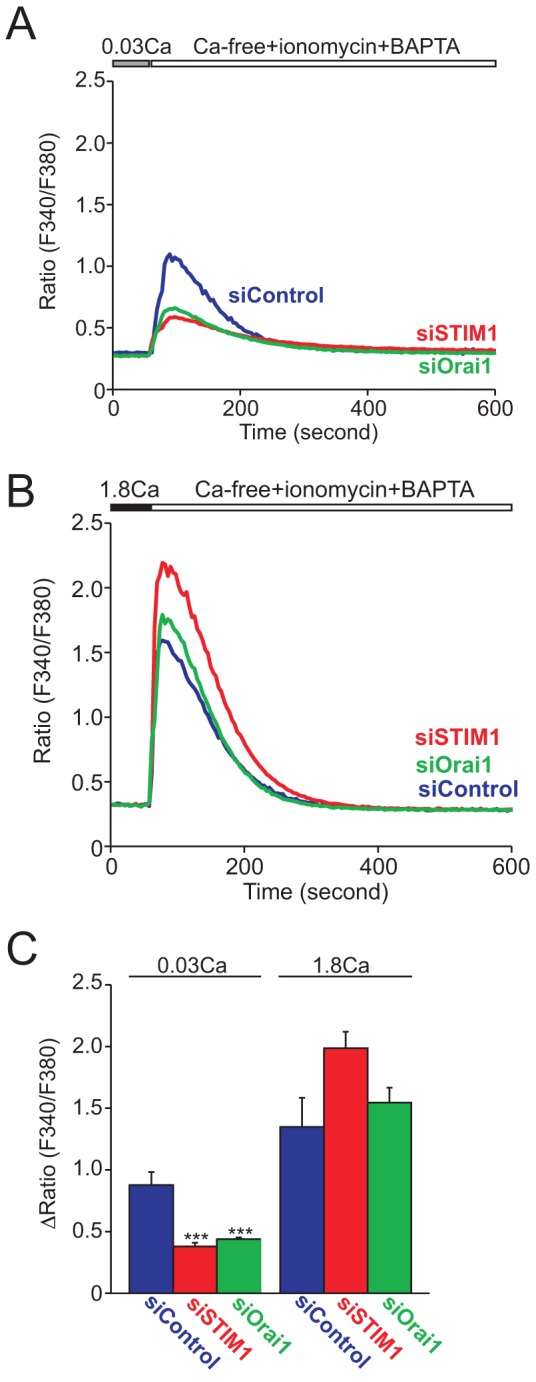

Knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai1 reduces intracellular Ca2+ store content in HaCaT cells cultured in low Ca2+ medium

Strikingly, in STIM1 siRNA-transfected cells the passive Ca2+ leak when TG was first added was significantly suppressed (Fig. 2A). This reduction of Ca2+ release from TG-sensitive stores was completely restored by an additional 24-hour culture in 1.8 mM Ca2+-containing medium (Fig. 2B). Note in Fig. 2B the similar kinetics of release and decline in the [Ca2+]i signal upon thapsigargin addition. This indicates that the knockdown of STIM1 and Orai1 did not affect other aspects of cellular Ca2+ metabolism such as mechanisms of intracellular buffering or plasma membrane extrusion. Ca2+ release by TG was slightly lower in cells cultured with 0.03 mM Ca2+ than that in cells cultured with 1.8 mM Ca2+, suggesting that stores are partially depleted in the low extracellular Ca2+ concentration of 0.03 mM. A more reliable method to assess intracellular Ca2+ store content involves the use of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin together with the fast Ca2+ chelator BAPTA, thereby reducing the likelihood that the peak release of Ca2+ will be blunted by uptake into other intracellular organelles (e.g. mitochondria) (Bird et al., 2008). Consistent with the data of TG-induced Ca2+ leak (Fig. 2), siRNAs against STIM1 and Orai1 similarly suppressed the ionomycin peaks (Fig. 4). The reduction in response to ionomycin was clearly due to differences in ER Ca2+ stores because when ER stores were depleted by thapsigargin prior to ionomycin addition, there was no difference in the remaining release due to ionomycin (supplementary material Fig. S3). Increasing extracellular Ca2+ to 1.8 mM again restored the Ca2+ contents to levels comparable to those in control siRNA transfected cells. These results suggest that STIM1 and Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry is constitutively active in KCs and plays an important role in maintaining intracellular Ca2+ stores when cells are exposed to low Ca2+ environments.

Fig. 4.

Both STIM1 and Orai1 are important for maintenance of intracellular stored Ca2+ in HaCaT cells cultured in low Ca2+ medium. Average time courses of Ca2+ release from whole intracellular Ca2+ stores by ionomycin in siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells cultured in low (A) or high (B) Ca2+ medium. (C) Peak [Ca2+] rises after whole intracellular store depletion by 20 µM ionomycin. Data are means ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. ***P<0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses were abolished by knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai1 in HaCaT cells

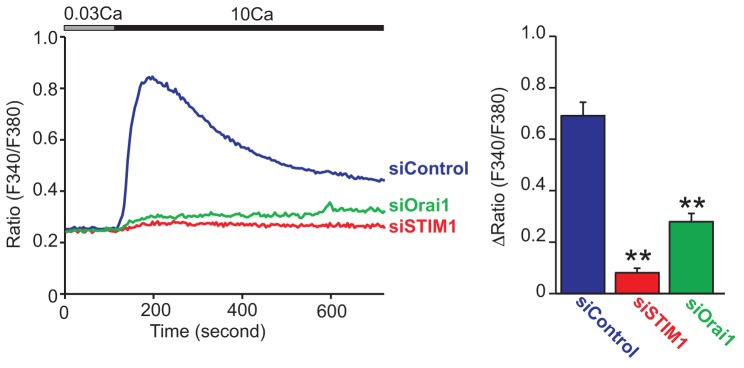

KCs are thought to sense an increase in extracellular Ca2+ concentration through Ca2+-sensing receptors (CaRs) on their cell surface and respond by undergoing differentiation (Tu et al., 2004). CaR is a G-protein-coupled receptor known to be coupled to Gαq protein which leads to induction of PLC-mediated Ca2+ responses (Hofer and Brown, 2003). Therefore, we next investigated how suppression of SOCE affects Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses. Cells were initially kept in 0.03 mM Ca2+-containing HBSS. In this cell line, raising extracellular Ca2+ to 1.8 mM Ca2+ only evoked minor Ca2+ responses in siControl-transfected cells possibly due to efficient global buffering of the Ca2+ influx within the cytoplasm (data not shown). However, increasing extracellular Ca2+ to 10 mM in control siRNA-transfected cells evoked an initial large Ca2+ increase followed by a lower but sustained increase (Fig. 5). These Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses were substantially reduced in either STIM1 or Orai1 siRNA-transfected cells. Similar to the responses to thapsigargin, the residual response in the Orai-knockdown cells was further reduced by either 2APB or Synta 66 (supplementary material Fig. S2).

Fig. 5.

Both STIM1 and Orai1 are required for Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses in HaCaT cells. Average time courses of 10 mM extracellular Ca2+-induced Ca2+ responses in siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells (left). Peak [Ca2+] rises of Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses (right). Data are means ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. **P<0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

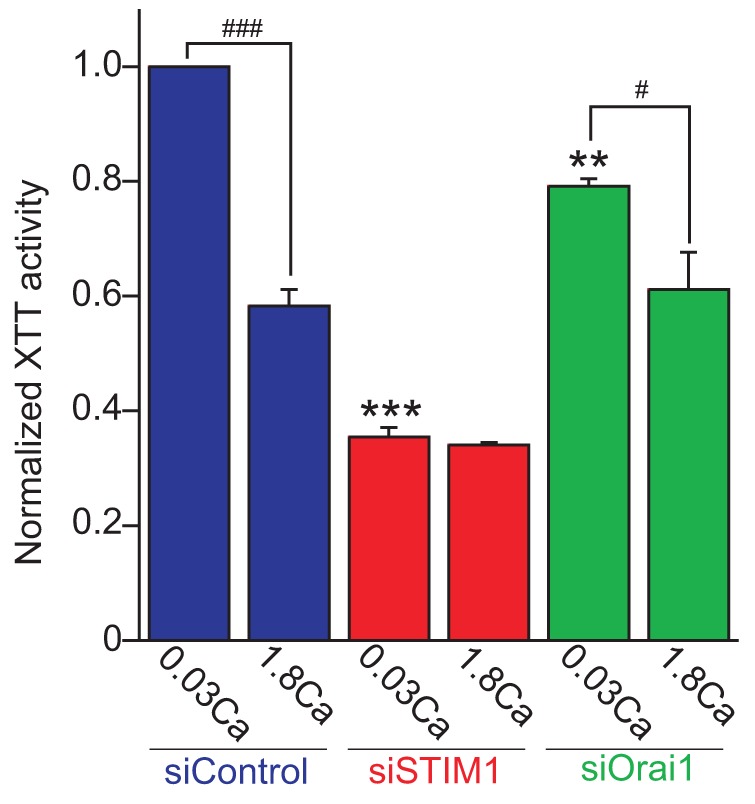

STIM1 and Orai1 are required for either normal proliferation or extracellular Ca2+-dependent proliferation arrest

Induction of KC differentiation is associated with proliferation arrest (Fuchs, 1993; Micallef et al., 2009). We and others have reported that STIM1 and Orai1 have critical roles in proliferation and cell cycle regulation (Abdullaev et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2011; Smyth et al., 2009). Therefore, next we tested the effect of STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown on proliferation of HaCaT cells by using an XTT cell proliferation assay (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 6, STIM1 knockdown strongly, and Orai1 knockdown to a lesser extent, diminished proliferation in 0.03 mM Ca2+-containing medium. These data suggest that STIM1 and Orai1 are important for growth of KCs in the undifferentiated condition. Strikingly, Ca2+ switch suppressed the proliferation of control cells by about half of that in 0.03 mM Ca2+ medium. However, Ca2+-switch-induced suppression of cell growth was not seen or reduced in STIM1- or Orai1-knockdown cells, respectively. These results suggest that STIM1 and Orai1-dependent signaling is important in maintaining proliferation of undifferentiated KCs and that Ca2+ switch triggers cell growth arrest by a STIM1- and Orai1-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 6.

STIM1 and Orai1 are important for normal cell growth and Ca2+-switch-induced growth arrest. Cells were cultured for 72 hours in 0.03 mM or 1.8 mM Ca2+-containing KGM-2. Cell growth was analyzed by the XTT cell proliferation assay. XTT activity in siSTIM1- and siOrai1-transfected cells is shown relative to that in siControl-transfected HaCaT cells in control low Ca2+ medium for 72 hours. Data are means ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01 versus siControl-transfected cells cultured in 0.03 mM Ca-KGM-2 for 72 hours. ###P<0.001, #P<0.05 comparison between low and high Ca2+ condition in same siRNA-transfected cells (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

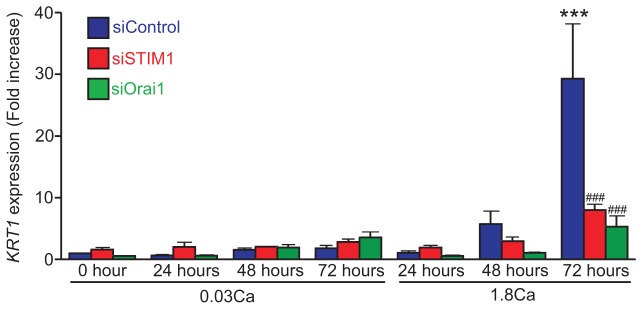

Ca2+-switch-induced expression of an early differentiation marker gene keratin 1 is diminished by either STIM1 or Orai1 knockdown

Intracellular Ca2+ increases upon Ca2+ switch are critical for the induction of keratinocyte differentiation (Li et al., 1995). To analyze the physiological effect of the defect of SOCE, we evaluated the expression of keratin 1 (KRT1) mRNA using qRT-PCR (Fig. 7). KRT1 is known to be an early differentiation marker of keratinocytes. KRT1 expression can be observed in the suprabasal layer of epidermis (Yuspa et al., 1988). In 0.03 mM Ca2+-containing medium, KRT1 expression remained almost unchanged over 72 hours in all siRNA-transfected cells. In contrast, following Ca2+ switch, an increase in KRT1 expression was first detected at 48 hours, and to a larger and statistically significant level at 72 hours in siControl-transfected cells. Strikingly, either STIM1- or Orai1-knockdown cells showed significant reduction of KRT1 mRNA expression, indicating that both proteins are important for the induction of KRT1 expression upon Ca2+ switch in HaCaT cells. These results indicate that Ca2+-switch-induced KC differentiation requires STIM1- and Orai1-mediated SOCE.

Fig. 7.

Both STIM1 and Orai1 are required for Ca2+-switch-induced differentiation marker expression in HaCaT cells. Ca2+-switch-induced expression of an early differentiation marker gene KRT1 in siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells. Fold increases of KRT1 expression relative to the sample at time 0 from siControl-transfected cell are shown. Data are means ± s.e.m. from four independent experiments. ***P<0.001 versus siControl-transfected cells time 0; ###P<0.001 versus siControl-transfected cells cultured in high Ca2+ medium for 72 hours (one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

Discussion

SOCE is the major Ca2+ influx pathway in most non-excitable cells and plays a critical role in cell fate decision (Parekh and Putney, 2005). Although the presence of SOCE has been reported in KCs (Korkiamäki et al., 2003; Tu et al., 2005), its importance in KC differentiation has not been assessed likely because the molecular players underlying SOCE, STIM1 and Orai1, have only recently been identified. In this study, we have discovered a number of important functions of both proteins with regard to Ca2+ in KCs, and in the physiologically important process of terminal differentiation. First, we demonstrated that STIM1 and Orai1 are responsible for SOCE in KCs. Second, we show that STIM1 and Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry is also important for maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ stores when KCs are exposed to a low Ca2+ environment. Third, we have shown that the Ca2+ response underlying induction of differentiation by Ca2+ switch is also completely lost following knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai1. Fourth, STIM1 and Orai1 are required for normal KC proliferation in low Ca2+ culture condition. Finally, we have demonstrated that STIM1 and Orai1 deficiencies lead to suppression of growth arrest and the expression of the early differentiation marker KRT1. These results strongly suggest STIM1 and Orai1-mediated SOCE plays a critical role in cell fate decision of KCs.

STIM and Orai proteins have 2 (STIM1 and 2) and 3 (Orai1, 2 and 3) homologues in mammals, respectively. Since STIM2 has higher affinity compared to STIM1, STIM2 has been suggested to function to maintain resting levels of ER Ca2+ in non-stimulated cells (Brandman et al., 2007). In contrast, STIM1 functions as an ER Ca2+ sensor to more drastic reduction upon the stimulation of Ca2+ release and activates Orai channels in the plasma membrane. In this study, siRNA-mediated STIM1 knockdown almost completely suppressed TG-induced Ca2+ entry as well as ICRAC, demonstrating that STIM1 is the major Ca2+ sensor to signal to Orai channels in response to store depletion in HaCaT KCs (Fig. 2). Unexpectedly, we found that the knockdown of STIM1 also attenuated TG-induced passive Ca2+ release from TG-sensitive Ca2+ stores in cells cultured in low Ca2+ medium, suggesting that STIM1 also functions to maintain basal ER Ca2+ levels in HaCaT cells cultured in low Ca2+ medium. Orai1 knockdown also caused strong suppression of TG-induced SOCE and diminished ER Ca2+ levels in cells cultured in low Ca2+ medium. However, in 1.8 mM Ca2+-containing medium, there was no difference in the store Ca2+ contents in cells lacking either STIM1 or Orai1. Thus, STIM1 and Orai1, and by inference SOCE, appear to be required to maintain Ca2+ stores in undifferentiated KCs, either because of their constitutive activity or because of signaling from external humoral factors.

KC differentiation by Ca2+ switch is thought to result from activation of the G-protein- and PLC-coupled CaR expressed in the plasma membrane (Tu et al., 2004). CaR is one of the class of receptors preferentially coupled with Gq and Gi proteins (Hofer and Brown, 2003). In this study, we demonstrated that increasing extracellular Ca2+ induced large and sustained Ca2+ increases in control cells, which were almost completely abolished in either STIM1- or Orai1-knockdown cells. This is consistent with previous finding that Ca2+-switch-induced Ca2+ responses were completely blocked by the treatment of 2-APB, a relatively specific inhibitor of STIM–Orai-mediated SOCE, in normal human keratinocytes (Tu et al., 2008). We did not observe any Ins(1,4,5)P3-receptor-mediated Ca2+ release from ER in STIM1- or Orai1-knockdown cells. It is possible that STIM1- and Orai1-knockdown cells do not maintain sufficient ER Ca2+ content to give a measurable release as suggested by the data in Fig. 3. Alternatively, CaR-mediated Ca2+ release might be too small to be detected by our methods. Ca2+ switch with 1.8 mM Ca2+ which is sufficient to induce differentiation in HaCaT cells, could not evoke visible Ca2+ responses possibly because the responses are subtle and are sufficiently buffered to prevent large changes in global Ca2+ concentration. We considered the possibility that knockdown of STIM1 or Orai1 might affect the expression of CaR; we obtained a weak signal for CaR by qRT-PCR, although there was no visible change with knockdown of STIM1 or Orai1. We have not been able to successfully detect CaR by western blotting with the currently available antibodies.

KC differentiation is associated with cell cycle arrest at G0 (Fuchs, 1993). In our study, Ca2+ switch reduced cell proliferation by nearly half in control cells (Fig. 6). However, this Ca2+-switch-induced suppression of proliferation was absent or reduced in STIM1- or Orai1-knockdown cells, respectively. Furthermore, proliferation of undifferentiated cells was diminished by either STIM1 or Orai1 knockdown. Thus, STIM1 and Orai1 are required for both steady state proliferation as well as Ca2+-switch-induced suppression of proliferation, suggesting that SOCE may have at least two important roles in KC physiology. How STIM1 and Orai1 might contribute to a steady state proliferation in low Ca2+ medium is unclear. However, STIM1- and Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry is apparently constitutively active in cells cultured in low Ca2+ medium, probably due to constitutive reduction of stored Ca2+ (Figs 2, 4), suggesting that this constitutive SOCE may be required for normal growth of KCs. With regard to cell growth arrest, it has been reported that the calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway, which is known to require STIM1- and Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry for its activation, regulates Ca2+-switch-induced cell cycle arrest via expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27 (Santini et al., 2001). Therefore, it is likely that STIM1 and Orai1-mediated Ca2+ entry plays an important role in KC growth arrest by activating NFAT signaling pathway.

The sequential expression of differentiation marker genes is one of the features of epidermal development (Yuspa et al., 1988). Since Ca2+ signaling is an early event after the stimulation of cells, we analyzed the contribution of STIM1 and Orai1 to the expression of an early differentiation marker of KRT1 (Fig. 7). Expression of KRT1 occurs mainly in the suprabasal layer and stratum spinosum in human epidermis (Yuspa et al., 1988). It has been reported that HaCaT cells differentiate in response to elevated Ca2+ in a manner similar to normal epidermal keratinocytes, but HaCaT cells require somewhat higher extracellular Ca2+ concentration and a longer time to launch the differentiation process (Micallef et al., 2009; Sakaguchi et al., 2003). As shown in Fig. 7, KRT1 expression appeared 72 hours after Ca2+ switch in our HaCaT cells. We attempted to analyze KRT1 protein expression in the same time course, but the expression was not sufficient to reliably detect the protein by western blot. We could not extend the incubation times because the increasing cell density caused an increase in KRT1 expression, independently of Ca2+. It is noteworthy that STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown did not affect the Ca2+-independent, cell density-dependent KRT1 expression (data not shown). This is consistent with the previous report that once keratinocyte cultures reach confluence, they start to express KRT1 genes and are no longer affected by the extracellular Ca2+ concentration (Poumay and Pittelkow, 1995). In this study, the signaling mechanisms linking STIM1- and Orai1-mediated SOCE and KRT1 expression remain elusive. Previous studies identified a regulatory element for Ca2+-dependent KRT1 expression in its 3′-flanking DNA sequence which is predicted to contain an activating protein (AP)-1 binding site (Huff et al., 1993; Rothnagel et al., 1993). It has been reported that c-Fos, one of the AP-1 transcription factors, expression is dependent on SOC channel activity in rat mast cells (Chang et al., 2006). Therefore, it is possible that STIM1 and Orai1 are required for the activation of AP-1 transcription factors in HaCaT cells. Alternatively, NFAT which is activated downstream of STIM1- and Orai1-mediated SOCE may regulate KRT1 expression in an indirect manner, since an NFAT inhibitor cyclosporin A suppresses KRT1 expression in murine KCs (Santini et al., 2001) and HaCaT cells (data not shown). It has been demonstrated that the expression of p21 depends on NFAT activity although the promoter of p21 has a DNA binding sequence for specificity protein (SP) 1/SP2 transcription factors but not that for NFAT. In fact, NFAT transactivates p21 gene promoter in synergism with Sp1/Sp2 (Santini et al., 2001). Therefore, it is possible that KRT1 expression is regulated by similar cooperative mechanism between NFAT and AP-1.

In conclusion, we have shown that STIM1 and Orai1 constitute a major Ca2+ influx pathway in KCs. This Ca2+ entry is required for the maintenance of stored Ca2+ levels in intracellular organelles in the undifferentiated condition and for Ca2+ signaling in the induction of KC differentiation. Through these Ca2+-influx-dependent processes, STIM1 and Orai1 play dual roles in KC physiology in both steady state proliferation and in signaling the onset of differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and siRNA transfection

HaCaT cells were cultured in KGM-2 (Lonza) supplemented with 0.03 mM CaCl2 and maintained at 37°C in a humidifier incubator set at 5% CO2. Culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days. To knockdown endogenous STIM1 and Orai1, cells were transfected with siRNAs by using Hiperfect (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, 5 nM-siRNA–Hiperfect complex was added onto 1×106 cells in 100-mm tissue culture dish. The culture medium was exchanged 6 hours after transfection. Cells were incubated for 2–3 days and replated to 6-well plates at a cell density of 0.5–1.5×105 cells per well and transfected with siRNAs again. Cells were stimulated with 1.8 mM Ca2+-containing KGM-2 2 days after the second siRNA transfection and used for experiments as indicated. Target sequences of siRNA against human STIM1 and Orai1 were as described previously (Mercer et al., 2006).

Cell lysis and western blotting

HaCaT cells were lysed in RIPA buffer [137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM sodium orthovanadate and protease inhibitor cocktail (Rosch)]. Cell lysates were resolved by a 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-human STIM1 (Prosci; 1∶3000), anti-human Orai1 (Sigma; 1∶5000), anti-actin (Sigma; 1∶3000). The bands were scanned and the density of each band was determined using ImageJ software.

Ca2+ imaging

Measurement of changes in [Ca2+]i was carried out as previously described (DeHaven et al., 2008). Cells were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-5F. The fluorescence ratio images were recorded from cells incubated in HBSS (in mM): 145 NaCl, 3 KCl, 0.3 or 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH). CaCl2 was omitted in Ca2+-free solution.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell currents were measured as described previously (DeHaven et al., 2007; DeHaven et al., 2008). The standard extracellular HBSS contained (in mM): 145 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 CsCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose and 10 HEPES (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). The standard divalent free solution (DVF) was prepared by removing the CaCl2 and MgCl2 from HBSS and adding 0.1 mM EGTA. The intracellular pipette solution contained: 145 mM cesium methanesulfonate, 10 mM BAPTA, 10 mM HEPES and 8 mM MgCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH) together with 20 µM Ins(1,4,5)P3 (hexasodium salt). Currents were acquired with pCLAMP-10 (Axon Instruments) and analyzed with Clampfit (Axon Instruments).

We noted that knockdown of STIM1 caused morphological changes in the majority of cells, such that they were much more flattened and virtually impossible to patch. Thus, patch-clamp experiments were carried out on the minority of cells showing minimal morphological changes. It is possible that these cells had somewhat higher levels of residual STIM1, and this may explain why partial, albeit diminished Icrac was seen in these cells.

XTT cell proliferation assay

An XTT assay was carried out by following the manufacturer’s instruction (ATCC). Briefly, siRNA-transfected HaCaT cells were seeded onto 96-well plates at a cell density of 3×103 cells/well. Cells were cultured in 0.03 mM or 1.8 mM Ca2+-containing KGM-2 for 72 hours. After addition of XTT reagent, 96-well plates were incubated for 6 hours until an orange color developed. Absorbance values at the wavelength of 475 nm and 660 nm were measured using a microtiter plate reader. Average of blank-subtracted absorbance was calculated from triplicate readings and normalized to that of siControl-transfected cells cultured 72 hours in 0.03 mM Ca2+-containing KGM-2.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For quantitative RT-PCR, total RNAs were extracted from HaCaT cells with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). cDNA synthesis was performed with Omniscript (Qiagen), using 0.5 µg total RNA, and quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with the ABI Prism 7000 Instrument (Applied Biosystems), using specific oligonucleotides [human KRT1, forward 5′-ATTTCTGAGCTGAATCGTGTGATC-3′, reverse 5′-CTTGGCATCCTTGAGGGCATT-3′ (Micallef et al., 2009); GAPDH, forward 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′, reverse 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′].

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding

This research was supported by the intramural program, National Institutes of Health [Project #01 ES090087]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.115980/-/DC1

References

- Abdullaev I. F., Bisaillon J. M., Potier M., Gonzalez J. C., Motiani R. K., Trebak M. (2008). Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 103, 1289–1299 10.1161/01.RES.0000338496.95579.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B., Lehen’kyi V., Roudbaraki M., Flourakis M., Charveron M., Bordat P., Polakowska R., Prevarskaya N., Skryma R. (2008). TRPC channels determine human keratinocyte differentiation: new insight into basal cell carcinoma. Cell Calcium 43, 492–505 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech D. J. (2012). Orai1 calcium channels in the vasculature. Pflugers Arch. 463, 635–647 10.1007/s00424-012-1090-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikle D. D. (2010). Vitamin D and the skin. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 28, 117–130 10.1007/s00774-009-0153-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G. S., DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Putney J. W., Jr (2008). Methods for studying store-operated calcium entry. Methods 46, 204–212 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O., Liou J., Park W. S., Meyer T. (2007). STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell 131, 1327–1339 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S., Fatherazi S., Presland R. B., Belton C. M., Roberts F. A., Goodwin P. C., Schubert M. M., Izutsu K. T. (2006). Evidence that TRPC1 contributes to calcium-induced differentiation of human keratinocytes. Pflugers Arch. 452, 43–52 10.1007/s00424-005-0001-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. C., Nelson C., Parekh A. B. (2006). Ca2+ influx through CRAC channels activates cytosolic phospholipase A2, leukotriene C4 secretion, and expression of c-fos through ERK-dependent and -independent pathways in mast cells. FASEB J. 20, 2381–2383 10.1096/fj.06-6016fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. F., Chiu W. T., Chen Y. T., Lin P. Y., Huang H. J., Chou C. Y., Chang H. C., Tang M. J., Shen M. R. (2011). Calcium store sensor stromal-interaction molecule 1-dependent signaling plays an important role in cervical cancer growth, migration, and angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15225–15230 10.1073/pnas.1103315108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbellay B., Arnaudeau S., König S., Jousset H., Bader C., Demaurex N., Bernheim L. (2009). STIM1- and Orai1-dependent store-operated calcium entry regulates human myoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 5370–5380 10.1074/jbc.M806726200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Boyles R. R., Putney J. W., Jr (2007). Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17548–17556 10.1074/jbc.M611374200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Boyles R. R., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr (2008). Complex actions of 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate on store-operated calcium entry. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19265–19273 10.1074/jbc.M801535200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotto G. P. (1999). Signal transduction pathways controlling the switch between keratinocyte growth and differentiation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 10, 442–457 10.1177/10454411990100040201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A. (2006). A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441, 179–185 10.1038/nature04702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. (1993). Epidermal differentiation and keratin gene expression. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 17, 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima M., Tomita T., Janoshazi A., Putney J. W. (2012). Alternative translation initiation gives rise to two isoforms of Orai1 with distinct plasma membrane mobilities. J. Cell Sci. 125, 4354–4361 10.1242/jcs.104919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer A. M., Brown E. M. (2003). Extracellular calcium sensing and signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 530–538 10.1038/nrm1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff C. A., Yuspa S. H., Rosenthal D. (1993). Identification of control elements 3′ to the human keratin 1 gene that regulate cell type and differentiation-specific expression. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 377–384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. Y., Putney J. W. (2012). Orai1-mediated calcium entry plays a critical role in osteoclast differentiation and function by regulating activation of the transcription factor NFATc1. FASEB J. 26, 1484–1492 10.1096/fj.11-194399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone L. S., Graham S. J., Dziadek M. A. (2010). STIM proteins: integrators of signalling pathways in development, differentiation and disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 1890–1903 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01097.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkiamäki T., Ylä–Outinen H., Koivunen J., Peltonen J. (2003). An intact actin-containing cytoskeleton is required for capacitative calcium entry, but not for ATP-induced calcium-mediated cell signaling in cultured human keratinocytes. Med. Sci. Monit. 9, BR199–BR207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Tucker R. W., Hennings H., Yuspa S. H. (1995). Chelation of intracellular Ca2+ inhibits murine keratinocyte differentiation in vitro. J. Cell. Physiol. 163, 105–114 10.1002/jcp.1041630112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Kim M. L., Heo W. D., Jones J. T., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr, Meyer T. (2005). STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 15, 1235–1241 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Fivaz M., Inoue T., Meyer T. (2007). Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9301–9306 10.1073/pnas.0702866104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J. C., Dehaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Wedel B., Boyles R. R., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr (2006). Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24979–24990 10.1074/jbc.M604589200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micallef L., Belaubre F., Pinon A., Jayat–Vignoles C., Delage C., Charveron M., Simon A. (2009). Effects of extracellular calcium on the growth-differentiation switch in immortalized keratinocyte HaCaT cells compared with normal human keratinocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 18, 143–151 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M., Essin K., Hill K., Beschmann H., Rubant S., Schempp C. M., Gollasch M., Boehncke W. H., Harteneck C., Müller W. E.et al. (2008). Specific TRPC6 channel activation, a novel approach to stimulate keratinocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33942–33954 10.1074/jbc.M801844200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh A. B., Putney J. W., Jr (2005). Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol. Rev. 85, 757–810 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. Y., Hoover P. J., Mullins F. M., Bachhawat P., Covington E. D., Raunser S., Walz T., Garcia K. C., Dolmetsch R. E., Lewis R. S. (2009). STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell 136, 876–890 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S., Bikle D. D., Mancianti M. L., Cline P., Hincenbergs M. (1990). Calcium regulation of growth and differentiation of normal human keratinocytes: modulation of differentiation competence by stages of growth and extracellular calcium. J. Cell. Physiol. 143, 294–302 10.1002/jcp.1041430213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S., Menon G. K., Bikle D. D., Elias P. M. (1993). Localization and quantitation of calcium pools and calcium binding sites in cultured human keratinocytes. J. Cell. Physiol. 154, 101–112 10.1002/jcp.1041540113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poumay Y., Pittelkow M. R. (1995). Cell density and culture factors regulate keratinocyte commitment to differentiation and expression of suprabasal K1/K10 keratins. J. Invest. Dermatol. 104, 271–276 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12612810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proksch E., Brandner J. M., Jensen J. M. (2008). The skin: an indispensable barrier. Exp. Dermatol. 17, 1063–1072 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J., DiGregorio P. J., Yeromin A. V., Ohlsen K., Lioudyno M., Zhang S., Safrina O., Kozak J. A., Wagner S. L., Cahalan M. D.et al. (2005). STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 169, 435–445 10.1083/jcb.200502019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross K., Whitaker M., Reynolds N. J. (2007). Agonist-induced calcium entry correlates with STIM1 translocation. J. Cell. Physiol. 211, 569–576 10.1002/jcp.20993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothnagel J. A., Greenhalgh D. A., Gagne T. A., Longley M. A., Roop D. R. (1993). Identification of a calcium-inducible, epidermal-specific regulatory element in the 3′-flanking region of the human keratin 1 gene. J. Invest. Dermatol. 101, 506–513 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi M., Miyazaki M., Takaishi M., Sakaguchi Y., Makino E., Kataoka N., Yamada H., Namba M., Huh N. H. (2003). S100C/A11 is a key mediator of Ca(2+)-induced growth inhibition of human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Cell Biol. 163, 825–835 10.1083/jcb.200304017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini M. P., Talora C., Seki T., Bolgan L., Dotto G. P. (2001). Cross talk among calcineurin, Sp1/Sp3, and NFAT in control of p21(WAF1/CIP1) expression in keratinocyte differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9575–9580 10.1073/pnas.161299698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J. T., Petranka J. G., Boyles R. R., DeHaven W. I., Fukushima M., Johnson K. L., Williams J. G., Putney J. W., Jr (2009). Phosphorylation of STIM1 underlies suppression of store-operated calcium entry during mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1465–1472 10.1038/ncb1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu C. L., Oda Y., Komuves L., Bikle D. D. (2004). The role of the calcium-sensing receptor in epidermal differentiation. Cell Calcium 35, 265–273 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu C. L., Chang W., Bikle D. D. (2005). Phospholipase cgamma1 is required for activation of store-operated channels in human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124, 187–197 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23544.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu C. L., Chang W., Xie Z., Bikle D. D. (2008). Inactivation of the calcium sensing receptor inhibits E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion and calcium-induced differentiation in human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3519–3528 10.1074/jbc.M708318200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M., Peinelt C., Beck A., Koomoa D. L., Rabah D., Koblan–Huberson M., Kraft S., Turner H., Fleig A., Penner R.et al. (2006). CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312, 1220–1223 10.1126/science.1127883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Bikle D. D. (1999). Phospholipase C-γ1 is required for calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20421–20424 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuspa S. H., Hennings H., Tucker R. W., Jaken S., Kilkenny A. E., Roop D. R. (1988). Signal transduction for proliferation and differentiation in keratinocytes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 548, 191–196 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb18806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. L., Yeromin A. V., Zhang X. H., Yu Y., Safrina O., Penna A., Roos J., Stauderman K. A., Cahalan M. D. (2006). Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 9357–9362 10.1073/pnas.0603161103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.