Summary

We assess current practice patterns of US neurologists in patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), and radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) using case-based surveys. For CIS, 87% recommended initiation of disease-modifying therapy (DMT) with MRI brain lesions. An injectable DMT was recommended by 90%–98% for treatment-naive, mild RRMS patients. There was 97% consensus to treat highly active RRMS, but no consensus on therapy choice. With RIS, there was consensus not to initiate treatment with brain but no spinal MRI lesions. Current US treatment patterns emphasize MRI in MS diagnosis and subsequent treatment decisions, treatment of early disease, aggressive initial treatment of highly active MS, and close patient monitoring.

Approved multiple sclerosis (MS) therapies and medications undergoing clinical evaluation can reduce patient relapses and slow MS progression,1 but definitions and documentation of clinical progression are variable and there is currently insufficient class I evidence for a detailed MS treatment algorithm. The current weight of evidence does not favor a particular MS treatment option among interferon-β (IFNβ) preparations and glatiramer acetate (GA), which have modest clinical efficacy and require frequent self-injection, but are generally well tolerated.2,3 The lack of definitive clinical evidence to guide MS treatment decisions has become increasingly important with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the additional therapies natalizumab, an anti-α4-integrin monoclonal antibody for once monthly infusion, and fingolimod, the first oral disease-modifying therapy (DMT). Both drugs are effective in treating relapsing MS, but carry risks not seen with injectable DMTs.3,4 Appropriate therapy selection to maximize patient benefit will be increasingly complex as additional MS therapeutics receive regulatory approval.5

Although consensus opinions of MS experts cannot replace evidence-based guidance, in the absence of sufficient trial data, they can help guide clinical decision-making. This study used a survey of US MS expert opinion to document current approaches to MS treatment and management based on individual experience with FDA-approved MS therapies.

METHODS

Survey participants were MS experts identified from the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) list of 207 MS treatment centers in the United States. Participants were self-selected based on willingness to complete the surveys. All survey responses were deidentified prior to data analyses, and no individual responses were known to the Steering Committee (O.K., A.E.M., C.T., and J.T.P.).

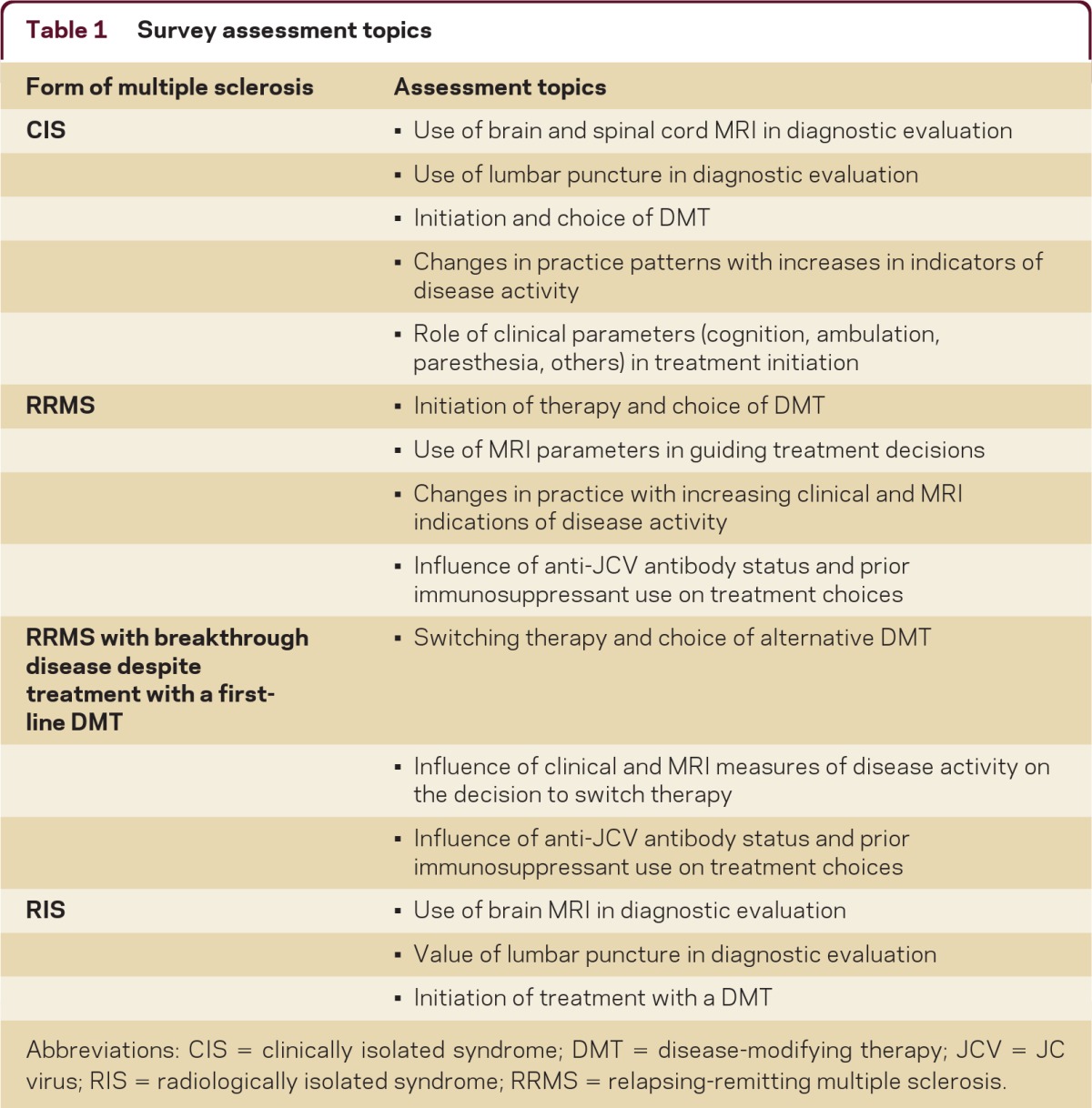

A modified Delphi process was used to assess current MS practice patterns. The 2 serial, case-based surveys contained questions designed by the Steering Committee to determine the influence and use of various diagnostic and clinical parameters in clinical decisions pertaining to DMT initiation, switching, and choice (table 1). Both surveys were Web-based. Survey results for CIS, RRMS, and radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) are presented below, while data for SPMS and PPMS are presented in a separate article on pages 58–66 of this issue. These surveys were developed independent of any CMSC input, and they were distributed 4 months after FDA approval of fingolimod for US marketing and prior to publication of the 2010 revised MS diagnostic criteria.6

Table 1.

Survey assessment topics

Abbreviations: CIS = clinically isolated syndrome; DMT = disease-modifying therapy; JCV = JC virus; RIS = radiologically isolated syndrome; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

Treatment initiation persisted with progressively worse cases, but therapy choice became more divergent, with increased use of therapies with greater efficacy, in particular, natalizumab.

Consensus opinion was defined a priori by the Steering Committee as at least 75% agreement. The Steering Committee also differentiated among consensus (≥75%), unanimous (100%), and majority (≥50%) opinion. Summary statistics were generated using Microsoft Excel with no formal statistical analyses.

Detailed methods are provided in appendix e-1 at neurology.org/cp.

RESULTS

Respondents came from both academic (42%) and community (58%) MS treatment centers and represented a diverse range of US geographic regions and communities (figure e-1). Seventy-five individuals completed the first survey, and 71 of those also completed the second survey.

Practice patterns for CIS

Survey 1 case: A previously healthy 24-year-old woman presents with visual acuity loss in her right eye. Optic neuritis was confirmed, and results from a neurologic examination were normal.

There was consensus (99%) that optic neuritis without MRI data was not sufficient evidence for treatment initiation. With no brain MRI lesions, a majority of respondents (69%) would perform a spinal MRI. Establishing a patient baseline and clinical due diligence were the most frequent reasons for the scan. Conversely, only 20% of respondents would recommend a lumbar puncture (LP) to evaluate a patient with optic neuritis. This percentage decreased to 16% with definitive brain MRI lesions.

When this case was modified to include 5 brain MRI T2 lesions consistent with inflammatory demyelination without concurrent enhancement, there was consensus (87%) to initiate therapy, although 92% would also test for other causes of MRI changes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Lyme disease. If the case included a brain MRI showing 1 gadolinium-enhancing (Gd+) corpus callosum lesion, 3 periventricular lesions, and 1 cerebellar lesion on initial scan, there was consensus (97%) to initiate therapy, with 99% treating with a either an IFNβ or GA. Clinical parameters supporting therapy initiation included cognitive or motor deficits, excessive fatigue, heat sensitivity, and changes in bladder function. Performing a follow-up MRI was regarded as important; 75% of respondents selected a time frame of 3–6 months from a range of options, in part for confirmation of treatment effect.

Practice patterns for RRMS

Survey 1 case: A 25-year-old man with RRMS and 2 attacks in the last 4 years is treatment naive and presents with a normal neurologic examination. A recent MRI reveals 5 nonenhancing T2 lesions in the brain.

Responses were unanimous to initiate treatment and all respondents selected treatment with a self-injectable DMT, but not a specific drug. Addition of 2 clinical attacks within 6 months leaving residual disability also generated unanimous agreement on initiation of therapy, with 32% selecting natalizumab for initial therapy and 1% selecting fingolimod, but there was no consensus DMT choice. With MRI evidence of brain hypointense T1 lesions (“black holes”) and atrophy, 39% recommended natalizumab, 4% recommended fingolimod, and 3% recommended either natalizumab or fingolimod. It is notable that a majority of respondents would treat patients with first-line therapies (IFNβ or GA) even if the patient experienced 2 relapses within the past 6 months and had evidence of more severe lesion activity as measured by MRI.

There was consensus (97%) to perform a follow-up MRI, but there was no consensus on when it should be performed, although 93% selected a time frame of 12 months or less.

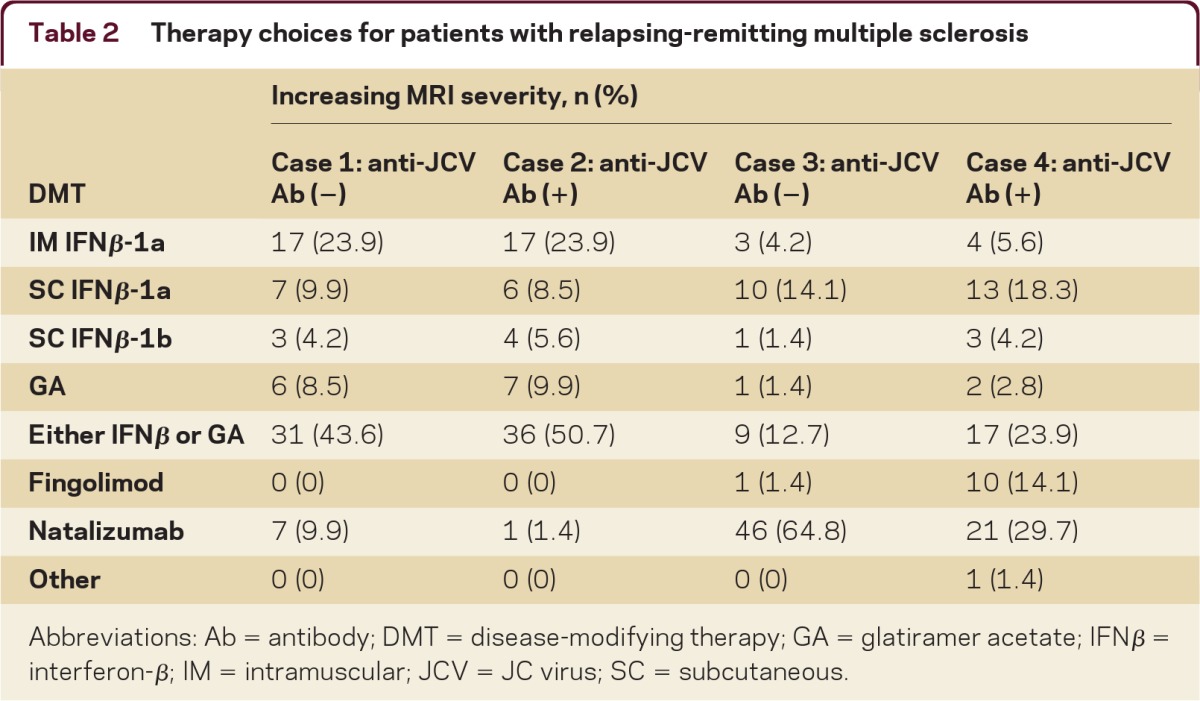

Survey 2 case: A 25-year-old man with RRMS and 2 attacks in the last 4 years is treatment naive and presents with a normal neurologic examination. A recent MRI reveals 5 nonenhancing T2 lesions in the brain. He is anti-JCV antibody (Ab) negative and has no prior history of immunosuppressant (mitoxantrone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, cladribine, rituximab, or chemotherapy) treatment.

Responses were unanimous to treat this patient, but there was no consensus therapy selection (table 2). The 10% of respondents recommending natalizumab decreased to 1% when the case was modified to a patient seropositive for anti-JCV Ab, a risk factor for developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Respondents unanimously recommended treatment initiation when the case included 2 attacks within the last 6 months resulting in residual disability, as well as an MRI scan showing more than 10 nonenhancing T2 lesions in the brain, brainstem, and spinal cord. There was no consensus on therapy choice, but for a treatment-naive, anti-JCV Ab negative patient, the majority (65%) would treat with natalizumab; this decreased to 30% for an anti-JCV Ab positive patient. Patient history of immunosuppressant use did not influence treatment choice for the majority of respondents (69%) if the patient was anti-JCV Ab positive. There was consensus that a follow-up MRI should be performed, with the majority (64%) of respondents selecting 3–6 months after treatment initiation and 89% selecting a time of 12 months or less.

Table 2.

Therapy choices for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

Abbreviations: Ab = antibody; DMT = disease-modifying therapy; GA = glatiramer acetate; IFNβ = interferon-β; IM = intramuscular; JCV = JC virus; SC = subcutaneous.

Practice patterns for RRMS and breakthrough disease

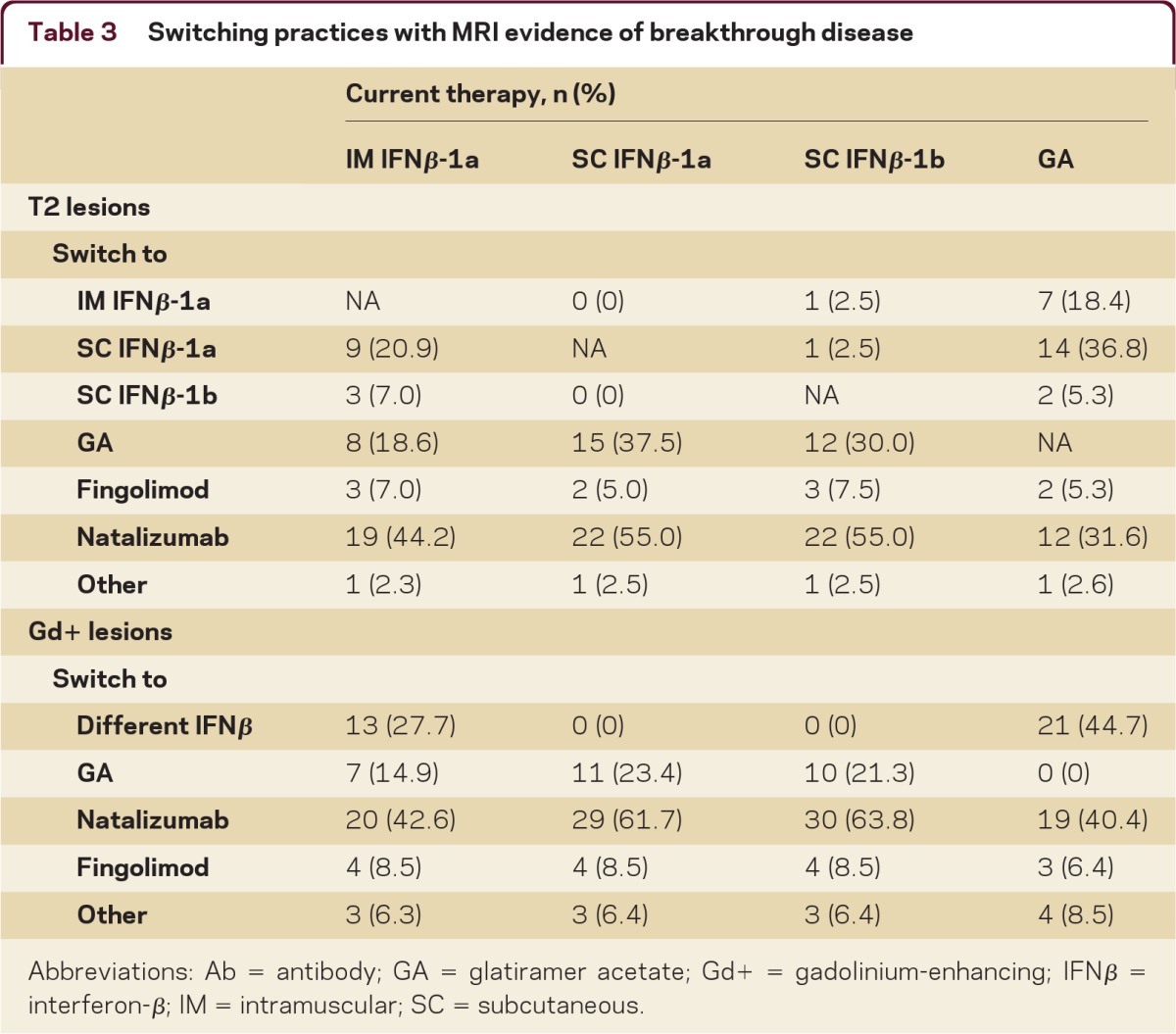

Survey 1 case: A 28-year-old woman with RRMS on glatiramer acetate for 2 years has 2 new, nonenhancing T2 lesions in the brain compared with an MRI performed 12 months earlier. The patient is clinically stable with no new symptoms.

When asked whether or not they would change this patient's treatment exclusive of IV steroids, a majority (51%) of respondents said that they would switch (table 3). Among those who would not switch, the majority (57%) would switch with 3–5 new asymptomatic T2 lesions; an additional 27% would switch with 6–10 new lesions. The remainder would not switch the patient's DMT regardless of the number of new T2 lesions due to the absence of symptoms.

Table 3.

Switching practices with MRI evidence of breakthrough disease

Abbreviations: Ab = antibody; GA = glatiramer acetate; Gd+ = gadolinium-enhancing; IFNβ = interferon-β; IM = intramuscular; SC = subcutaneous.

Survey respondents were also asked about switching between specific DMTs (table 3). As T2 lesion load increased, the majority of respondents would switch the patient from an IFNβ to natalizumab. Similarly, when the case scenario included increased Gd+ lesion load, 67% of respondents would switch the patient's DMT. However, there was no consensus DMT choice when switching with either T2 or Gd+ evidence of breakthrough disease.

Survey 2 case: A 28-year-old woman with RRMS on subcutaneous interferon β-1a for 2 years has 6 new T2 lesions without concurrent enhancement in the brain compared with an MRI performed 12 months earlier. The patient is clinically stable, is anti-JCV Ab negative, and has no prior history of immunosuppressant (mitoxantrone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, cladribine, rituximab, or chemotherapy) treatment, no interferon-neutralizing antibodies, and no new symptoms.

For this case, there was consensus (90%) to switch the patient's DMT, with clinically stable disease or no Gd+ lesions stated as reasons for not switching. Among respondents recommending switching, there was consensus (84%) to switch to natalizumab, with the others switching to GA (9%), fingolimod (5%), or other (unspecified) (2%). If the patient was anti-JCV Ab positive, there was still consensus to switch, but there was no consensus on DMT choice, with selections split among fingolimod (42%), natalizumab (36%), GA (20%), and other (unspecified) (2%). Although there was no consensus, the majority (70%) believed that 3 new, nonenhancing T2 lesions over a 12-month period supported switching therapies.

There was consensus to switch therapies with 2 motor/sensory attacks over 6 months (99%) or 12 months (89%). For patients on an IFNβ experiencing motor/sensory attacks, there was no consensus on therapy choice, with respondents selecting switching to natalizumab (range, 42%–57%) or GA (range, 18%–33%). For patients on GA, the majority of respondents would switch DMTs, with choices split between an IFNβ (46%) and natalizumab (42%).

Evolving MRI technologies have facilitated improved MS diagnosis and estimation of disease course. However, radiologic and clinical correlations remain imperfect.

The majority of respondents (62%) agreed that the length of time on a DMT influenced switching recommendations, but there was no consensus on time on therapy before considering switching (table e-1). The majority of respondents would recommend 6–12 months as the minimum treatment duration before switching to another DMT for reasons of insufficient efficacy.

Practice patterns for RIS

Case: A 31-year-old woman underwent brain MRI for evaluation of migraines. MRI revealed incidental white matter pathology in the CNS (4 nonenhancing, perpendicularly oriented, periventricular T2 lesions) highly suggestive of inflammatory demyelinating pathology. Results from a neurologic examination were normal; past medical history and family medical history were unremarkable.

The widespread use of MRI has resulted in increased detection of white matter pathology of unknown etiology or prognostic significance. The majority of respondents (63%) would not perform a LP on this patient, but there was consensus (88%) to perform a spinal MRI and consensus (89%) not to initiate treatment if the spinal MRI results were normal. There was also consensus (88%) to perform a follow-up MRI, with 91% of respondents selecting a time frame within 12 months.

DISCUSSION

Treatment initiation for CIS

Assessment of current practice patterns in CIS diagnosis and treatment initiation showed that only 1% of respondents would treat a patient with optic neuritis and no brain MRI activity. However, 87% would initiate treatment for optic neuritis plus 5 nonenhancing T2 lesions. An estimated 50%–80% of CIS patients also have MRI lesions suggestive of MS, and most but not all evidence from trials and observational studies suggests that early treatment initiation for CIS delays the onset of clinically definite MS.7 Consensus on performing a follow-up MRI within 3–6 months of treatment initiation was another interesting finding; published data indicate that MRIs may be conducted in this time frame to confirm disease diagnosis or to assess treatment responses.8,9 It will be important to evaluate these possibilities in future research studies. Also, the common use of spinal cord MRI in CIS represents a shift in practice from the recommendations in the previous McDonald MS diagnostic criteria,10 but responses are aligned with current recommendations.6 However, prerequisites for MS diagnosis include not only dissemination in time and space by MRI, but also exclusion of alternative causes11 using paraclinical tests including CSF analysis.12,13 Although the survey results showed a strong trend for limited LP use, LP results can be critical for certain differential diagnoses.

Treatment of RRMS and switching therapies

MS specialists probably have the most experience managing RRMS since this is the most common clinical form. Respondents were unanimous in electing to initiate treatment even for a patient with a mild presentation. Although the specific DMT choice was not unanimous, all respondents selected either IFNβ or GA for initial therapy. Treatment initiation persisted with progressively worse cases, but therapy choice became more divergent, with increased use of therapies with greater efficacy, in particular, natalizumab.

Providing information on prior immunosuppressant use and anti-JCV Ab status into the case scenarios influenced responses, including the finding that 30%–36% of respondents would select natalizumab for an anti-JCV antibody positive patient. In January 2012, one year after the surveys were completed, the US FDA authorized the STRATIFY JCV™ antibody test (Quest Diagnostics) as the first blood test for qualitative detection of anti-JCV antibodies for stratifying PML risk, and the US label for natalizumab was updated to identify the presence of anti-JCV antibodies as a risk factor for developing PML.4 Currently, 180,600 patient-years of natalizumab exposure have shown an overall PML incidence of 2.02 per 1,000 patients (Biogen Idec, data on file, December 2011 update). Also, the surveys were administered 2 months after FDA approval of fingolimod and before publication of recent trial data.14 Greater experience with fingolimod will likely influence therapy choices.

The high initial use of natalizumab in patients with aggressive disease and negative anti-JCV Ab status independent of Gd+ brain lesions or brain atrophy may reflect increasing confidence in using natalizumab in patients with a known antibody status. There was consensus on performing a follow-up MRI, but, as noted above, the trend toward earlier MRI following treatment initiation may reflect the desire for an earlier assessment of treatment response.

A majority (51%), but not a consensus, of respondents would switch therapies with MRI evidence alone. Currently no robust evidence supports superior efficacy for any 1 IFNβ therapy over another or indicates a therapeutic benefit to switching between IFNβ and GA. Nevertheless, these data reflect a trend for increasing integration of MRI into MS treatment decisions.6,9,10 Switching therapies may become more common with greater clinical experience using newer DMTs, potentially increasing physician confidence using more complex agents and treatment regimens. Treatment efficacy must be carefully and methodically considered together with the potential patient risks associated with switching.

Treatment initiation for RIS

The term RIS describes patients with an initial brain MRI suggestive of MS but no signs or symptoms of the illness.15 In RIS, asymptomatic spinal cord lesions are a significant positive predictor of increased risk for acute or progressive events, independent of brain MRI lesions.16 Increasing recognition of RIS in parallel with widespread use of MRI has prompted debate on how best to manage this group of patients. Survey results suggest that MS specialists consider RIS as possibly indicative of clinically definite MS risk and placed importance on MRI and clinical follow-up, but initiating treatment for RIS was unlikely.

Although some patients with RIS meet the majority of diagnostic criteria,17 other conditions exhibit similar presentations. The lack of clinical MS activity or of evidence of a decline in neurologic function can make definitive diagnosis challenging and discourage treatment initiation. Patients with brain evidence for RIS are reported to be at increased risk for progression to CIS or definite MS after a median of 5.4 years,15 with asymptomatic spinal cord lesions predicting RIS patient progression to CIS or PPMS.16 Evolving MRI technologies have facilitated improved MS diagnosis and estimation of disease course. However, radiologic and clinical correlations remain imperfect; standardization of scan acquisition and image analysis is required; and patients must have symptoms to receive a diagnosis of MS.18–20

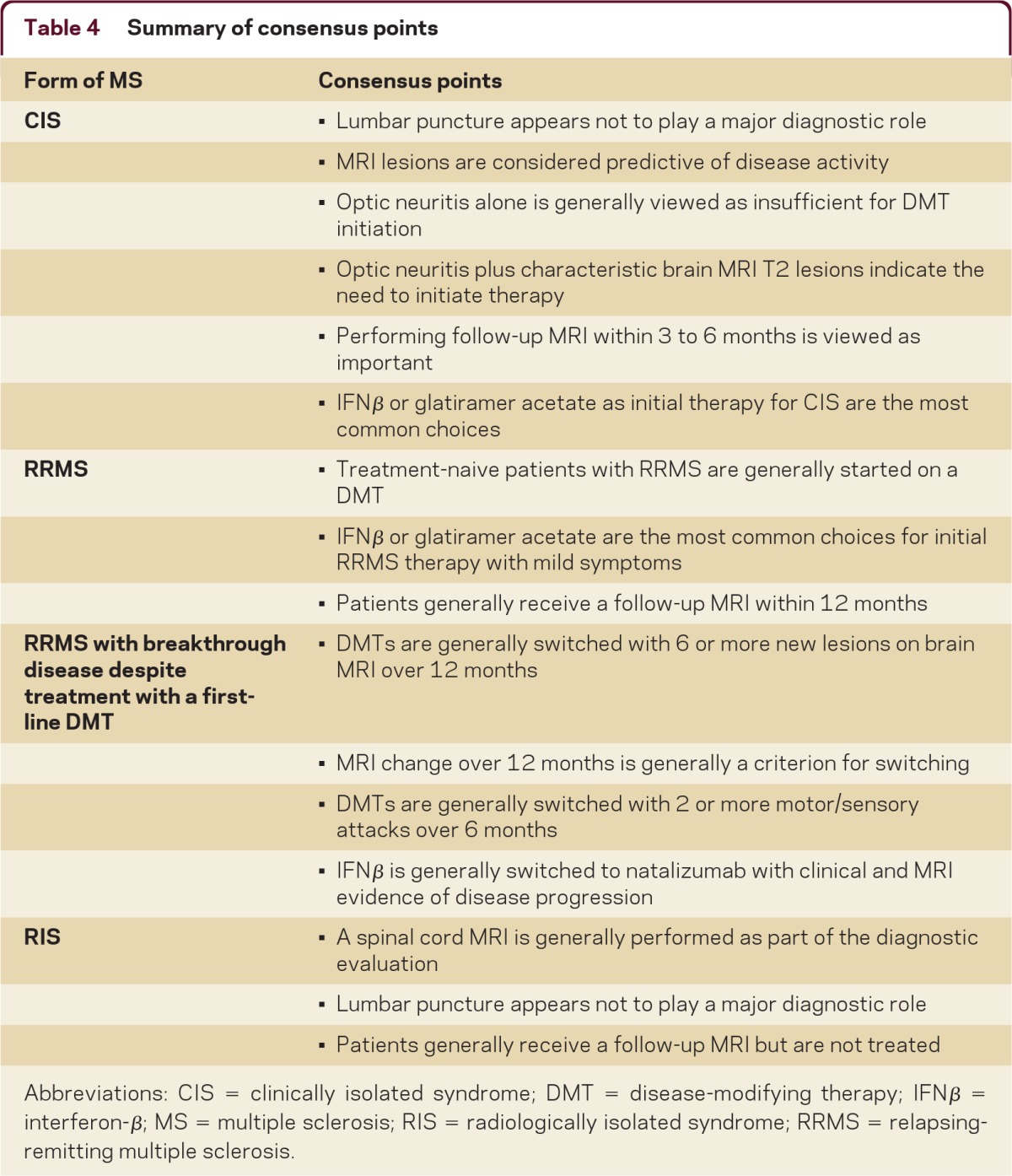

The current research effort was conducted with the goal of gaining an understanding of the current diagnostic and treatment practices of MS specialists at US MS treatment centers and providing prescribing neurologists with information to optimize the care of patients with MS seen in everyday practice. The survey results reflect current MS practice patterns for CIS, RRMS, and RIS according to US-based survey responders. It was not intended to and does not assess individual patient understanding of the benefit–risk profiles of current therapy options. These findings may not be applicable in other countries on the basis of potential treatment access limitations such as limitations due to reimbursement restrictions in public payor programs. Also, these results cannot replace evidence-based guidance and professional society guidelines, as are being developed in other therapeutic areas with rapidly evolving treatment options.e1–e3 Table 4 summarizes the points of clear consensus from the present surveys. With the evolving MS treatment landscape and the rapid development of new diagnostic and prognostic indicators for MS, there may be utility in developing targeted educational programs to improve patient care and periodically reassessing real-world clinical practice.

Table 4.

Summary of consensus points

Abbreviations: CIS = clinically isolated syndrome; DMT = disease-modifying therapy; IFNβ = interferon-β; MS = multiple sclerosis; RIS = radiologically isolated syndrome; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the individuals who took time to participate in this survey; Rohit Baskhi, MD, and Mariko Kita, MD, for their contributions to and support of this study; and Joshua Safran and Jacqueline Cannon with Infusion Communications for copyediting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental data www.neurology.org/cp

STUDY FUNDING

Biogen Idec convened a Steering Committee to develop the content of this article and paid committee members for their participation. In addition, Biogen Idec paid honoraria for survey participation and provided funding for study logistics and editorial support. Biogen Idec reviewed drafts and had input into the development of the surveys, reviewed the manuscript, and provided feedback on the manuscript to the authors. The authors had full editorial control of the surveys and manuscript and provided their final approval of all content.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Tornatore serves on speakers' bureaus for Biogen Idec and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; serves on scientific advisory boards for Biogen Idec and Novartis; and receives research support from Biogen Idec. Dr. Phillips serves as a consultant and on scientific advisory boards for and has received speaker honoraria from Acorda Therapeutics Inc., Biogen Idec, Genzyme Corporation, Novartis, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. Dr. Khan has received funding for travel or speaker honoraria from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Novartis, and Biogen Idec; serves as a consultant for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Novartis, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Roche, and Genzyme Corporation; serves on speakers' bureaus for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Novartis, Genzyme Corporation, and Biogen Idec; and receives research support from Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Novartis, Biogen Idec, Genzyme Corporation, Roche, the NIH, and the National MS Society. Dr. Miller serves on scientific advisory boards for sanofi-aventis, Biogen Idec, GlaxoSmithKline, EMD Serono, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo, Merck Serono, Novartic, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Acorda Therapeutics; serves as a consultant for Acorda Therapeutics, Biogen Idec, CVS Caremark, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis; serves on the editorial board of Continuum; has received speaker honoraria from Merck Serono and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd.; receives/has received research support from Acorda Therapeutics, Novartis, Genzyme Corporation, sanofi-aventis, and Biogen Idec; and has reviewed medico-legal cases as a defense expert. Dr. Barnes is an employee of Infusion Communications, which received funding from Biogen Idec.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smith B, Carson S, Fu R, et al. Drug class review: disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis: final update 1 report [Internet]. In: Drug Class Reviews. Portland, OR: Oregon Health & Science University; 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clegg A, Bryant J. Immunomodulatory drugs for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of clinical and cost effectiveness. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2001;2:623–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aktas O, Küry P, Kieseier B, Hartung HP. Fingolimod is a potential novel therapy for multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2010;6:373–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. TYSABRI (natalizumab) prescribing information (2012). http://www.tysabri.com/en_US/tysb/site/pdfs/TYSABRI-pi.pdf Accessed February 4, 2011

- 5. Gold R. Oral therapies for multiple sclerosis: a review of agents in phase III development or recently approved. CNS Drugs 2011;25:37–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bates D. Treatment effects of immunomodulatory therapies at different stages of multiple sclerosis in short-term trials. Neurology 2011;76(suppl 1):S14–S25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swanton JK, Rovira A, Tintore M, et al. MRI criteria for multiple sclerosis in patients presenting with clinically isolated syndromes: a multicentre retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:677–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

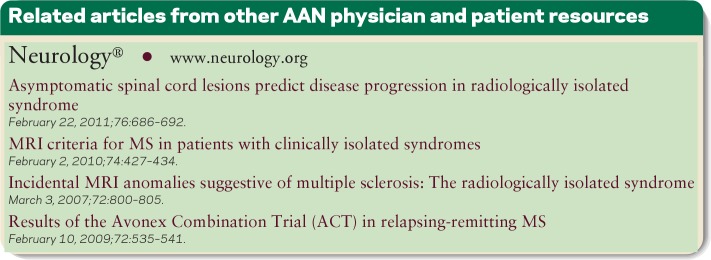

- 9. Montalban X, Tintoré M, Swanton J, et al. MRI criteria for MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology 2010;74:427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2001;50:121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller DH, Weinshenker BG, Filippi M, et al. Differential diagnosis of suspected multiple sclerosis: a consensus approach. Mult Scler 2008;14:1157–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tumani H, Deisenhammer F, Giovannoni G, et al. Revised McDonald criteria: the persisting importance of cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Ann Neurol 2011;70:520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Freedman MS, Thompson EJ, Deisenhammer F, et al. Recommended standard of cerebrospinal fluid analysis in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a consensus statement. Arch Neurol 2005;62:865–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khatri B, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Comparison of fingolimod with interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised extension of the TRANSFORMS study. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okuda DT, Mowry EM, Beheshtian A, et al. Incidental MRI anomalies suggestive of multiple sclerosis: the radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2009;72:800–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okuda DT, Mowry EM, Cree BA, et al. Asymptomatic spinal cord lesions predict disease progression in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2011;76:686–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, et al. Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain 1997;120:2059–2069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barkhof F, Simon JH, Fazekas F, et al. MRI monitoring of immunomodulation in relapse-onset multiple sclerosis trials. Nat Rev Neurol 2011;8:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Filippi M, Rocca MA. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the study of multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, prognosis and understanding disease pathophysiology. Acta Neurol Belg 2011;111:89–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poser CM, Brinar VV. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2001;103:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.