Summary

Solutions to the major riddles in movement disorders are appearing at a breathtaking pace: 1) loss-of-function mutations in PRRT2, which encodes a cell surface protein expressed in neurons, have been found in many patients with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias; 2) mutations in CIZ1, which encodes a protein involved in cell-cycle control at the G1-S checkpoint, have been identified in a small percentage of patients with cervical dystonia; and 3) finally, after many years of genetics and identification of more than 25 disease-associated genes, cellular studies related to the pathobiology of hereditary spastic paraplegia are converging on defects in modeling the endoplasmic reticulum and membrane trafficking. On the treatment front, the distinctive syndromes of faciobrachial dystonic seizures with anti-LRI1 antibodies and anti-N-methyl-d-aspartic acid encephalitis with orobuccolingual dyskinesias are becoming increasingly recognized by clinicians as imminently treatable conditions. Also on the treatment front, the first phase I trial of MRI-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound for essential tremor has been completed and intraoperative MRI is currently being used to place electrodes in the brains of patients with medically intractable dystonia. Definitive etiologies and efficacious treatments for non–Parkinson disease movement disorders are no longer wishful thinking.

Historically, neurologists have been fascinated by the phenomenology and pathogenesis of non–Parkinson disease (PD) movement disorders such as the dystonias, paroxysmal dyskinesias, and hereditary spastic paraplegias. Technology drives change. With recent advances in “new-generation” massively parallel sequencing of DNA, molecular neuroimmunology, and cell biology, the mysteries of non-PD movement disorders are falling like a deck of cards. On the therapeutic front, intraoperative MRI is being used to guide targeted ultrasound for noninvasive creation of lesions and facilitate placement of deep brain stimulation electrodes in patients who may be poorly suited for microelectrode recordings. Improved understanding of disrupted cellular pathways facilitates identification of therapeutic targets for preventative and disease-modifying treatments. Definitive molecular diagnoses enhance clinical confidence and direct neurologists to the appropriate form of therapy. Noninvasive and minimally invasive neurosurgical techniques offer the hope of reduced costs and access for a larger spectrum of patients. Clearly, the future is bright for patients with non-PD movement disorders and their treating neurologists.

Paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia

The paroxysmal dyskinesias may be primary or secondary to a wide variety of neural insults, and are divided into 4 major categories based on precipitating factors: paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia (PKD), paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia (PNKD), paroxysmal exertion-induced dyskinesia (PED), and paroxysmal hypnogenic dyskinesia (PHD). PKD attacks are brief and precipitated by movement. In contrast, attacks in PNKD are much longer and typically occasioned by factors such as caffeine, anxiety, or temperature extremes.

PKD has been known by several names, including episodic kinesigenic dyskinesia and paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis. PKD is relatively rare but important to recognize. Primary PKD is an autosomal dominant neurologic disorder of incomplete penetrance. In patients with PKD, recurrent, brief attacks of involuntary movement are usually triggered by sudden voluntary movement. These attacks usually begin in childhood or early adulthood and may include various combinations of dystonia, chorea, and athetosis affecting the face, trunk, arms, and legs. In the majority of patients, paroxysmal dystonia is the sole or predominant clinical manifestation. PKD often improves with age and the vast majority of patients show a favorable response to relatively low dosages of anticonvulsant medications, particularly carbamazepine and phenytoin. Due to the seemingly bizarre phenomenology of PKD and dramatic response to treatment, some patients are dismissed as psychogenic.

PKD, infantile convulsions and choreoathetosis (ICCA), and benign infantile epilepsy (BFIE) had been linked to the pericentromeric region of chromosome 16 for over 10 years. Just recently, massively parallel exome sequencing was combined with linkage analysis and confirmatory Sanger sequencing to identify several distinct loss-of-function frameshift mutations leading to protein truncation or nonsense-mediated decay of proline-rich transmembrane protein 2 (PRRT2) in familial and sporadic PKD.1,2 A much smaller percentage of cases were caused by missense mutations. A hotspot mutation in PRRT2 was found in Chinese, Caucasian, and Japanese patients. The clinical spectrum of PRRT2 mutations includes cases of ICCA, BFIE, some “PNKD-like” syndromes, and PED.1–3 Not all patients with classic carbamazepine-responsive PKD harbor mutations in coding regions of PRRT2. Genetic testing for PRRT2 mutations should be considered in patients with clinical features of PKD, ICCA, and BFIE in order to establish a definitive etiology and avert unnecessary searches for secondary causes.

Defects at the G1-S cell-cycle checkpoint cause cervical dystonia

Primary dystonia is usually of adult onset, can be familial, and frequently involves the cervical musculature. Genetic etiologies for cervical dystonia have been lacking despite the fact that approximately 10% of patients have one or more first- or second-degree relatives with dystonia. Although rare, large multiplex pedigrees provide an opportunity to identify genes that may be associated with sporadic cases of cervical dystonia. To achieve this goal, linkage and haplotype analyses were combined with solution-based whole-exome capture and massively parallel sequencing in a large Caucasian pedigree with adult-onset, primary cervical dystonia. A missense mutation in CIZ1, which encodes CIZ1, Cip1-interacting zinc finger protein 1, was identified in affected family members.4 High-resolution melting and Sanger sequencing were used to identify additional mutations in patients with familial or sporadic adult-onset cervical dystonia. Clinical genetic testing of patients with sporadic cervical dystonia cannot be recommended since currently available data suggest that only 1% of patients with cervical dystonia harbor mutations in CIZ1.4

CIZ1 is only the third gene to be associated with primary dystonia, the first being TOR1A. DYT1 dystonia is typically associated with a ΔGAG mutation in exon 5 of TOR1A and mean age at onset is approximately 10 years. TOR1A encodes the AAA+ protein torsinA. Clinical signs usually appear unilaterally in a leg. THAP1 and CIZ1 are the first genes to be causally associated with cases of late-onset sporadic dystonia.4,5 In contrast to CIZ1, THAP1 mutations tend to manifest earlier in life (mean age at onset = 16.8 years) and may be associated with more extensive anatomical involvement.5

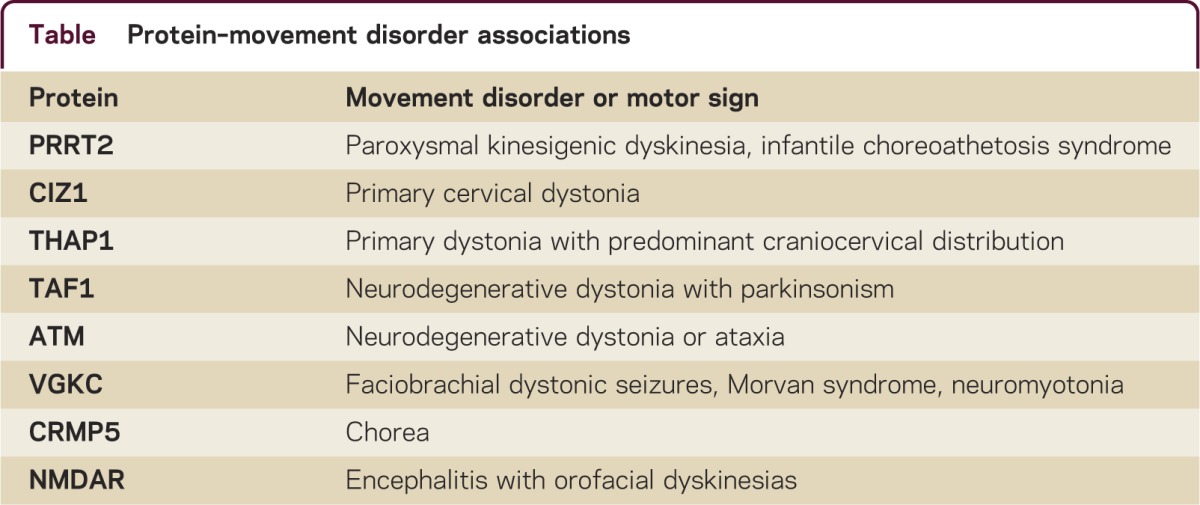

CIZ1 is a p21Cip1/Waf1-interacting zinc finger protein expressed in brain and involved in DNA synthesis and cell-cycle control. Mutations in CIZ1 may cause adult-onset, primary cervical dystonia by disrupting G1-S cell-cycle control during development or in the mature CNS. The eukaryotic cell cycle consists of 4 distinct phases: gap 1 (G1) phase, synthesis (S), gap 2 (G2), and mitosis (M). The G1 phase is also known as the growth phase during which cells prepare for the DNA synthesis of the S phase. During the S phase DNA is synthesized and all chromosomes are replicated. The G1-S cell-cycle checkpoint is a pathway that controls commitment of cells in their transition from the end of G1 to S. In brief, the G1-S cell-cycle checkpoint ensures that the cell is fully prepared for DNA synthesis. The G1-S checkpoint appears to be a pathway of cellular pathology in dystonia. Two proteins associated with primary dystonia, CIZ1 and THAP1, and 2 associated with neurodegenerative dystonia, TAF1 and ATM, are directly involved in the G1-S checkpoint pathway (table). Lubag or DYT3 may be due to deficiency of a neuronal isoform of TAF1.6 Variant ataxia-telangiectasia is due to recessive mutations in ATM and may present as primary-appearing dystonia.7 ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) is a serine/threonine kinase activated by DNA double-strand breaks and contributes to maintenance of cell-cycle arrest. In ataxia-telangiectasia, at least, defects in cell-cycle arrest lead to cell-cycle reentry in terminally differentiated Purkinje cells and apoptotic cell loss.8 Whether or not similar cellular events occur in primary dystonia remain to be established and will require analysis of human postmortem tissue and genetically engineered animal models. In any case, the veil has been lifted and therapeutic targets are in sight.

Table.

Protein–movement disorder associations

Distinctive paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic autoimmune movement disorders

Autoimmune movement disorders such as Sydenham chorea and the chorea associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome are well known to most neurologists. Similarly, paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration secondary to anti-Yo antibodies would be routinely included among the differential diagnoses of ataxia in a woman with ovarian cancer. On the other hand, the spectrum of distinctive paraneoplastic and nonparaneoplastic immune-mediated movement disorders is expanding, and prompt recognition may permit the diagnosis of an occult malignancy or resolution with immunotherapy.9 In this brief review, we focus on movement disorders associated with antibodies to the voltage-gated potassium channel (VGKC) complex, collapsing response mediator protein 5 (CRMP5), and the NR1 subunit of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors (NMDAR).

The VGKC complex includes leucine-rich glioma-activated 1 (LGI1), contactin-associated protein 2 (CASPR2), and contactin-2. Four relatively distinct but interrelated clinical syndromes are associated with VGKC antibodies: 1) faciobrachial dystonic seizures (FBDS), 2) limbic encephalitis, 3) Morvan syndrome, and 4) neuromyotonia. These syndromes show similarities in their time course and response to immunotherapy. Although there is some overlap in antibodies, neuromyotonia is typically associated with antibodies to CASPR2, and FBDS with antibodies to LGI1. Morvan syndrome is a complex syndrome with protean manifestations that may include neuromyotonia, dysautonomia with hyperhidrosis, insomnia, hallucinations, delusional thinking, and occasional seizures.10

The syndrome of FBDS is quite unique, and, in many patients, more closely resembles a paroxysmal movement disorder rather than limbic encephalitis with seizures.11 Affected individuals exhibit brief (<3 seconds), frequent (50/day), stereotyped paroxysmal dystonia, which characteristically affects one arm and the ipsilateral face. These events often precede limbic encephalitis with a median interval of 5 weeks. The mean age at onset for FBDS is over 50 years. Men are affected more frequently than women. Additional diagnostic clues include hyponatremia, which is present in over half of the affected individuals, and MRI high signal abnormalities in the hippocampus. Most commonly, there are no cells or oligoclonal bands on analysis of CSF. Patients typically respond to immunotherapy with steroids or IV immunoglobulin. A very small percentage of patients with FBDS will harbor an occult malignancy, most commonly small-cell carcinoma of the lung or a thymoma.

Chorea secondary to CRMP5 antibodies is usually paraneoplastic and most commonly associated with small-cell carcinoma of the lung or thymoma.9 Additional clinical features include limbic encephalitis, ataxia, neuropathy, uveitis, optic neuritis, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities on MRI. Treatment must be focused on identifying the underlying malignancy. Control of the chorea and other neurologic manifestations requires immunotherapy targeting T-cell–mediated mechanisms with cyclophosphamide.

The NMDAR functions as a heterotetramer with 2 NR1 and 2 NR2 subunits. In contrast to FBDS, patients with NMDAR antibodies develop a characteristic movement disorder 1 to 3 weeks after a psychiatric phase with delusions, hallucinations, mood changes, and disorientation.12,13 Patients then develop seizures and autonomic instability, which often precipitates admission to the intensive care unit. It is in the intensive care unit that the characteristic movement disorder with orofacial dyskinesias and choreoathetoid limb movements first appears. In some patients, however, particularly children, the movement disorder may be the initial manifestation. The orofacial dyskinesias may be rhythmic or semirhythmic.

The neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with NMDAR antibodies is much more common in females than males and usually appears before 50 years of age. Over half of adult women with NMDAR encephalitis harbor an ovarian teratoma—this percentage is lower in teenage girls. Young girls and men are usually not found to have a tumor. Although an early lymphocytic pleocytosis and oligoclonal bands are common, MRI is often normal. First-line therapy is tumor identification and removal. Immunotherapy begins with corticosteroids but may require IV immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, cyclophosphamide, or rituximab.

The complex genetics of hereditary spastic paraplegia points to common pathways of cellular dysfunction

Hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) is characterized by progressive lower extremity spasticity and weakness with significantly less upper extremity involvement. HSP can be divided into uncomplicated and complicated forms. Uncomplicated HSP is manifest as spasticity without other clinically important neural or non-neural features. In contrast, complicated forms of HSP may include one or more additional manifestations such as dementia or mental retardation, dystonia, neuropathy, amyotrophy, epilepsy, or thinning of the corpus callosum. The genetics of HSP includes dominant, recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial inheritance. The most common HSP is SPG4 due to mutations in SPAST which encodes the AAA+ protein spastin. To date, over 50 distinct genomic loci have been linked to HSP in one or more families and causal mutations have been identified for over 25 types of HSP. The almost bewildering collection of HSP-associated proteins (e.g., atlastin, spastin, NIPA1, reticulon 2, paraplegin, spatacsin, alsin, REEP1, spastizin, maspardin, erlin2, seipin, spartin) has been both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, this wealth of starting material offers endless opportunities for hypothesis-driven experiments and increases the probability of detecting functional interactions. On the other hand, it has been difficult to generate entirely unified theories of HSP pathogenesis.

HSP-related proteins can be grouped into partially overlapping functional classes: membrane trafficking and organelle shaping, mitochondrial regulation, lipid metabolism, and axon path finding.14,15 Although, at some level, all intracellular processes are interrelated, the relationships among a significant subset of HSP-related proteins are of unquestionable pathophysiologic significance. In particular, 3 of the most common autosomal dominant HSPs, including SGP4, are due to mutations of proteins involved in shaping the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Motility of the ER is dependent on microtubules and spastin is known to function as an ATP-dependent enzyme that severs microtubules. At the neuropathologic level, spastin deficiency is known to produce focal axonal swellings and impaired axonal transport. Recently, proof of mechanism studies have shown that microtubule-targeting drugs rescue the abnormal SPG4 pathologic phenotype in mouse models.16 Hopefully, humans are next. Patients should be reassured that scientists are in active pursuit of disease-modifying treatments for HSP.

New techniques for MRI-guided surgical treatment of essential tremor and dystonia

In recent years, deep brain stimulation has become increasingly employed in carefully selected patients with medically intractable essential tremor and dystonia. Many patients are poor surgical candidates or averse to an invasive procedure or chronically implanted device. Moreover, fully awake microelectrode recordings can be difficult to virtually impossible in some subjects with severe generalized dystonia. Therefore, new tools and approaches are needed in neurologists' and neurosurgeons' armamentaria.

Gamma knife radiosurgery has been used to treat essential tremor for over 15 years. However, gamma knife radiosurgery has Level U recommendation from the American Academy of Neurology for essential tremor due to lack of randomized multicenter trials with long-term follow-up. The effects of gamma knife radiosurgery are often modest,17 and, even in experienced hands, can be associated with temporary or permanent neurologic side effects in over 5% of patients.18 Alternatives to gamma knife radiosurgery and deep brain stimulation for essential tremor such as magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) are in development. In comparison to gamma knife radiosurgery, ultrasound may create more discrete lesions and may be associated with a significantly lower risk of delayed sequelae.19

Enrollment in the first MRgFUS essential tremor feasibility trial using the InSightec ExAblate Neuro system was completed in January 2012 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01304758). In brief, 15 patients underwent noninvasive ExAblate treatment to evaluate the safety and initial effectiveness of this investigational device. The ExAblate Neuro MRgFUS system (InSightec Ltd., Tirat Carmel, Israel) integrates MRI and high-intensity focused ultrasound for noninvasive, image-guided transcranial applications. The system enables intraprocedural MRI for therapy planning and real-time magnetic resonance thermal imaging feedback to monitor safety and efficacy. MRI facilitates real-time monitoring of tissue heating, and assessment of therapeutic outcome during and after therapy. Ultrasound lesioning is performed through an intact skull with no incisions or ionizing radiation. The system is integrated with a standard General Electric MRI system using a detachable table. In the scanner room, the patient lies on the table with the head immobilized in a stereotactic frame, and the helmet-like transducer is positioned around the head. A sealed water system with an active cooling and degassing capacity maintains the skull and skin surface at a comfortably low temperature. The neurologic community awaits data on long-term results, comparative efficacy, and the frequency of neurologic side effects.

Neuromodulation with implanted electrodes has shown efficacy in essential tremor, dystonia, and Parkinson disease. However, some patients are poorly suited for awake microelectrode recordings and structural mapping. One possible alternative is intraoperative MRI-guided implantation of electrodes using an MRI-compatible system (ClearPoint®, MRI Interventions, Inc.; Memphis, TN). The ClearPoint system has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use with both 1.5 T and 3.0 T MRI scanners. Current research is aimed at determining the comparative safety and effectiveness of this procedure in patients with dystonia and Parkinson disease (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00792532). Phantom and cadaver tests have shown that the ClearPoint system provides submillimeter accuracy for intraoperative MRI electrode placement.20

Non-Parkinson movement disorders: Five new things.

Mutations in PRRT2 cause paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia and infantile convulsions and choreoathetosis.

Some cases of adult-onset primary dystonia are due to mutations in genes (THAP1 and CIZ1) important at the G1-S cell-cycle checkpoint.

Faciobrachial dystonic seizures and anti-NMDAR encephalitis are associated with characteristic involuntary movements that enable rapid diagnoses and definitive treatments.

Interactions between microtubules and the endoplasmic reticulum are central to the pathophysiology of hereditary spastic paraplegia and may be amenable to small molecule therapeutics.

Intraoperative MRI permits noninvasive high-intensity focused ultrasound VIM thalamotomy for essential tremor and implantation of chronic electrodes for treatment of dystonia.

APPENDIX

Exome

The part of the genome formed by the coding portions of genes. In humans, the exome comprises approximately 1% of the genome.

Nonsense-mediated decay

A surveillance pathway that degrades mutant messenger RNA molecules that encode truncated proteins.

Missense mutation

Single nucleotide changes that result in substitution of one amino acid for another.

High-resolution melting

A fast and cost-effective method of mutation detection based on analyzing the temperature-dependent denaturation of double-stranded DNA.

AAA+ protein

The commonly used abbreviation for a large family of ATPases associated with diverse cellular activities. These proteins couple ATP hydrolysis with various activities such as protein folding or microtubule severing.

STUDY FUNDING

M. LeDoux is supported by the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, Tyler's Hope for a Dystonia Cure, Prana, CHDI, Merz, and NIH grants R01NS048458, R01NS060887, R01NS057722, R01NS058850, 5U01NS052592, 5U01AT000613, and U54NS065701.

DISCLOSURES

M. LeDoux serves on the speakers' bureaus for Lundbeck and Teva Neuroscience; serves on the Xenazine Advisory Board for Lundbeck and Azilect Advisory Board for Teva; and receives research support from the NIH, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, Tyler's Hope for a Dystonia Cure, Prana, CHDI, and Merz. Go to Neurology.org/cp for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen WJ, Lin Y, Xiong ZQ, et al. Exome sequencing identifies truncating mutations in PRRT2 that cause paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Nat Genet 2011;43:1252–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang JL, Cao L, Li XH, et al. Identification of PRRT2 as the causative gene of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias. Brain 2011;134:3493–3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heron SE, Grinton BE, Kivity S, et al. PRRT2 mutations cause benign familial infantile epilepsy and infantile convulsions with choreoathetosis syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2012;90:152–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao J, Uitti RJ, Zhao Y, et al. Mutations in CIZ1 cause adult onset primary cervical dystonia. Ann Neurol 2012;71:458–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeDoux MS, Xiao J, Rudzińska M, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in THAP1 dystonia: molecular foundations and description of new cases. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:414–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makino S, Kaji R, Ando S, et al. Reduced neuron-specific expression of the TAF1 gene is associated with X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism. Am J Hum Genet 2007;80:393–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders-Pullman R, Raymond D, Stoessl AJ, et al. Variant ataxia-telangiectasia presenting as primary-appearing dystonia in Canadian Mennonites. Neurology 2012;78:649–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Chen J, Vinters HV, et al. Stable brain ATM message and residual kinase-active ATM protein in ataxia-telangiectasia. J Neurosci 2011;31:7568–7577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panzer J, Dalmau J. Movement disorders in paraneoplastic and autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:346–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irani SR, Pettingill P, Kleopa KA, et al. Morvan syndrome: clinical and serological observations in 29 cases. Ann Neurol 2012;72:241–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irani SR, Michell AW, Lang B, et al. Faciobrachial dystonic seizures precede Lgi1 antibody limbic encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2011;69:892–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irani SR, Vincent A. The expanding spectrum of clinically-distinctive, immunotherapy-responsive autoimmune encephalopathies. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2012;70:300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, et al. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:63–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Matteis MA, Luini A. Mendelian disorders of membrane trafficking. N Engl J Med 2011;365:927–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackstone C. Cellular pathways of hereditary spastic paraplegia. Annu Rev Neurosci 2012;35:25–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fassier C, Tarrade A, Peris L, et al. Microtubule-targeting drugs rescue axonal swellings in cortical neurons from spastin knock-out mice. Dis Model Mech Epub 2012 Jul 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Lim SY, Hodaie M, Fallis M, et al. Gamma knife thalamotomy for disabling tremor: a blinded evaluation. Arch Neurol 2010;67:584–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young RF, Li F, Vermeulen S, Meier R. Gamma Knife thalamotomy for treatment of essential tremor: long-term results. J Neurosurg 2010;112:1311–1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medel R, Monteith SJ, Elias WJ, et al. Magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound surgery: part 2: a review of current and future applications. Neurosurgery Epub 2012 Jul 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Larson PS, Starr PA, Bates G, et al. An optimized system for interventional magnetic resonance imaging-guided stereotactic surgery: preliminary evaluation of targeting accuracy. Neurosurgery 2012;70(1 suppl operative):95–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]