Abstract

Background

The internal medicine milestones were developed to advance outcomes-based residency training and will play an important role in the next accreditation system.

Innovation

As an element of our program's participation in the internal medicine educational innovations project, we implemented a milestones-based evaluation process in our general medicine and pulmonary-critical care rotations on July 1, 2010.

Measures

Outcomes assessed included survey-rated acceptability to participating faculty, residents, and clinical competency committee members.

Results

Faculty and residents agreed that the milestones promoted a common understanding of what knowledge, skills, and attitudes should be displayed at particular points in residents' professional development and enhanced evaluators' ability to provide specific performance feedback. Most residents and faculty members agreed that the milestones promoted fairness and uniformity in the evaluation process. Clinical competency committee members agreed the milestones improved the quality of information available for deliberations and resulted in more uniform promotion standards. Faculty rated the use of too many milestones per form/tool at a mean of 7.3 (where 1 was minimally problematic, and 10 was maximally problematic) and the potential for evaluator fatigue (mean, 8.2) as the most significant challenges to the use of milestones. Eight of 12 faculty members would recommend milestones in other programs; 4 were uncertain.

Conclusions

Despite logistical challenges, educators and trainees found that milestones promoted a common understanding of what knowledge, skills and attitudes should be displayed at particular stages of training; permitted greater specificity in performance feedback; and enhanced uniformity and fairness in promotion decisions.

Editor's note: The online version of this article includes additional materials such as data tables, survey or interview forms, or assessment tools (412.1KB, zip) .

What was known

The educational milestones are an important part of the next accreditation system but their use in resident assessment is largely untested to date.

What is new

Implementation of the internal medicine milestones as part of an educational innovations project showed the acceptance of the milestones by faculty and residents.

Limitations

Single program study, and logistical challenges in milestone implementation particularly “evaluator fatigue.”

Bottom Line

Use of the internal medicine milestones for teaching and assessment promoted a common understanding of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes residents should acquire during their professional development and enhanced evaluators' ability to provide specific performance feedback.

Introduction

Internal medicine milestones were developed to advance outcomes-based residency training. Collectively, the milestones describe through observable behaviors the expected developmental trajectory of the competent internist. Shortly after a review of the draft set of milestones in 2009,1 our residency program sought to capitalize on the milestones' potential benefits. Prior to our annual program review, we had identified targets that appeared suitable for improvement through use of milestones. We hypothesized that their implementation would facilitate the identification and correction of curricular weaknesses, help to establish clear performance expectations, promote specific performance feedback, and enhance consistency in promotions decisions. As the next accreditation system (NAS)2 will rely upon “measurement and reporting of outcomes” via milestones, our experience in implementing a large-scale milestones-based evaluation process may be of interest to other programs and is described in this report.

Methods

Setting and Participants

This project took place within the internal medicine residency of New York Medical College at Westchester Medical Center, as an educational innovations project (EIP) initiative.3 Participants included 26 residents, 12 full-time key clinical faculty, 5 program leaders, and 10 clinical competency committee members.

Intervention

At our 2009 to 2010 annual program review, residency leaders outlined a plan for a new and comprehensive milestones-based training process. This was well received and led to five development sessions (2 hours each) that were attended by all 12 full-time faculty members, 5 program leaders, and 3 chief residents. A steering group was selected at the first session to guide further developmental efforts. From the 142 published milestones,1 the group produced mock evaluation forms for major rotations. These forms facilitated faculty voting that determined the contents of new evaluation tools as well as the scope and manner of milestones' use within the program. Approximately 10% to 20% of milestones were eliminated on grounds of lack of applicability or redundancy; no milestones were added to the mocked up forms. Separate small group discussions identified curricular weaknesses that were addressed through the creation of a number of new educational processes that relied upon direct observation of resident performance during key activities (entrustable professional activities [EPAs])4 such as managing care transitions, patient safety, and patient care in the clinic. The steering group integrated the milestones into pre-existing forms and the program's goals and objectives and designed a framework that included 11 landmark and 3 clinical competency committee evaluations. The landmark evaluations represented important developmental stages at which milestones-based data were used to make advancement decisions. From proposal to implementation, this project required 200 hours for the creation of evaluation tools and modification of program curricula, 120 hours for faculty development, 50 hours for leadership core faculty planning sessions, and 4 afternoon conferences to educate residents (see online box and Appendix for additional details regarding planning and implementation). No additional personnel were required to carry out the initiative; we were able to generate new, directly observed performance ratings by modifying existing activities so that no significant changes in resident or faculty work hours were necessary. A $10 000 grant from the Foundation for Innovations in Medical Education supported expenses related to development and dissemination of milestones-related educational materials. The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of New York Medical College and the Office of Clinical Trials and Westchester Medical Center; the new evaluation system went into use on July 1, 2010.

Outcomes

The impact of the new training curriculum was evaluated primarily through anonymous surveys sent to all participants after milestones had been in use for 7 months. To help establish content validity, surveys were patterned after questionnaires that had been developed within the EIP collaborative and were reviewed by a New York Medical College dean for medical education. Prior to distribution, surveys were tested for clarity and content by 2 faculty members and 3 residents who had participated in an earlier EIP milestones initiative. Focus sections included (1) demographics; (2) satisfaction with the milestones' ability to provide performance benchmarks and to enhance feedback (retrospective premilestone/postmilestone, on a 10-point ordinal scale where 10 was maximally satisfied); (3) impact on curricular development, fairness, and promotion standards (using a 5-point, Likert-scale, Agree Strongly, Somewhat, Neutral, Disagree Somewhat, Strongly); (4) advantages of milestones (using a 10-point ordinal-scale where 10 was maximally and 1 was minimally); and (5) disadvantages of milestones (using a 10-point ordinal-scale where 10 was maximally problematic and 1 was minimally problematic). Faculty and residents were asked to provide comments and to state whether they would recommend milestones to other programs. All residents and faculty surveyed had used conventional core competency-based evaluations during the preceding academic year and were therefore able to provide a comparative perspective of the 2 evaluation systems. Five program leaders were surveyed using a program leadership survey, 2 of whom also completed faculty and clinical competency committee surveys. Their responses are reported in the corresponding data sets. There was no other overlap among surveyed participants. We also reported the mean number of directly observed performance ratings completed for second- and third-year residents, pre and postmilestone implementation for academic years 2009 to 2010 and 2010 to 2011.

Analysis

Survey and resident evaluation data were analyzed using the two-tailed t test with independent variables and the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Statistical significance levels were Bonferroni corrected and set at P < .006 for faculty and P < .01 for resident survey results.

Results

Surveys: General Impressions

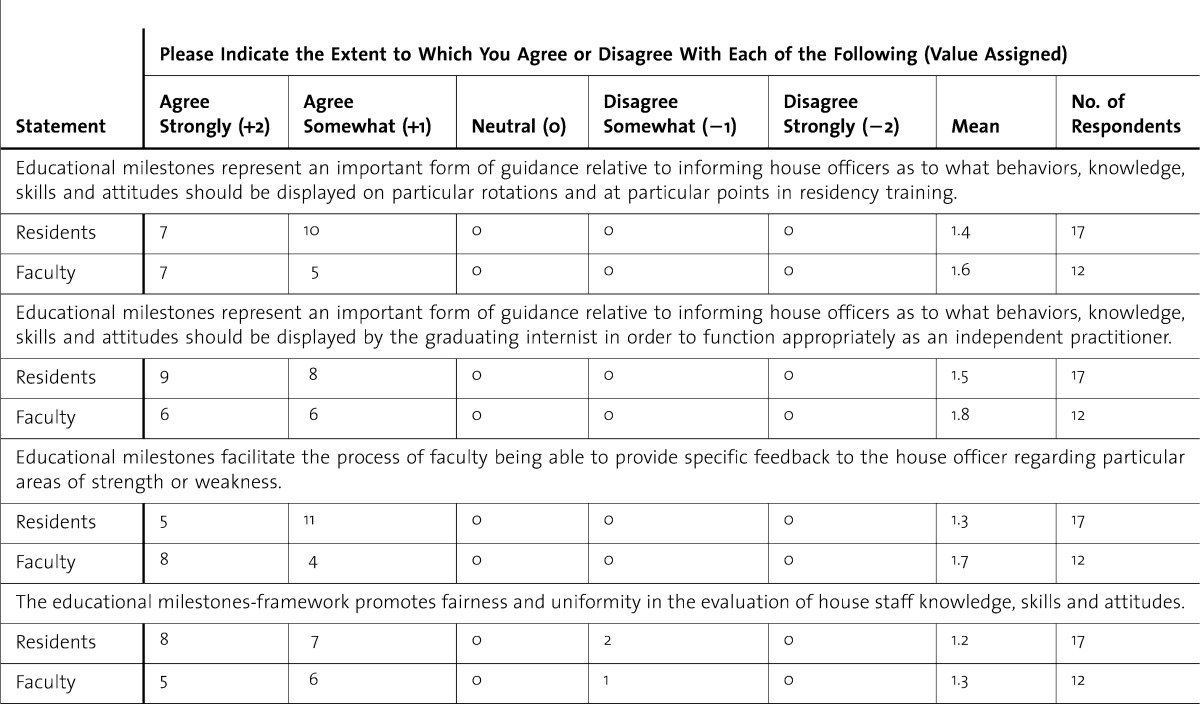

All faculty (12 of 12, 100%) and program leaders (5 of 5, 100%), 17of 26 (65%) residents, and 7 of 10 (70%) clinical competency members responded to the surveys. All responding key faculty (n = 12) and residents (postgraduate year [PGY]-2 and PGY-3 classes, n = 17) agreed either somewhat or strongly that milestones promoted a common understanding of what behaviors, knowledge, skills, and attitudes should be displayed at particular points in training and that milestones facilitated the evaluator's ability to provide specific feedback regarding strengths and weaknesses. Fifteen of 17 residents (88%) agreed somewhat or strongly that milestones promoted fairness and uniformity, while 10 of 12 faculty members rated milestones' ability to promote fairness at 8 or higher on a 10-point scale (table 1). Eight of 12 faculty members would “recommend to other institutions that their residency program adopt a milestones-based evaluations system,” while 4 were uncertain.

table 1.

Faculty and House Staff Survey Summary

Faculty

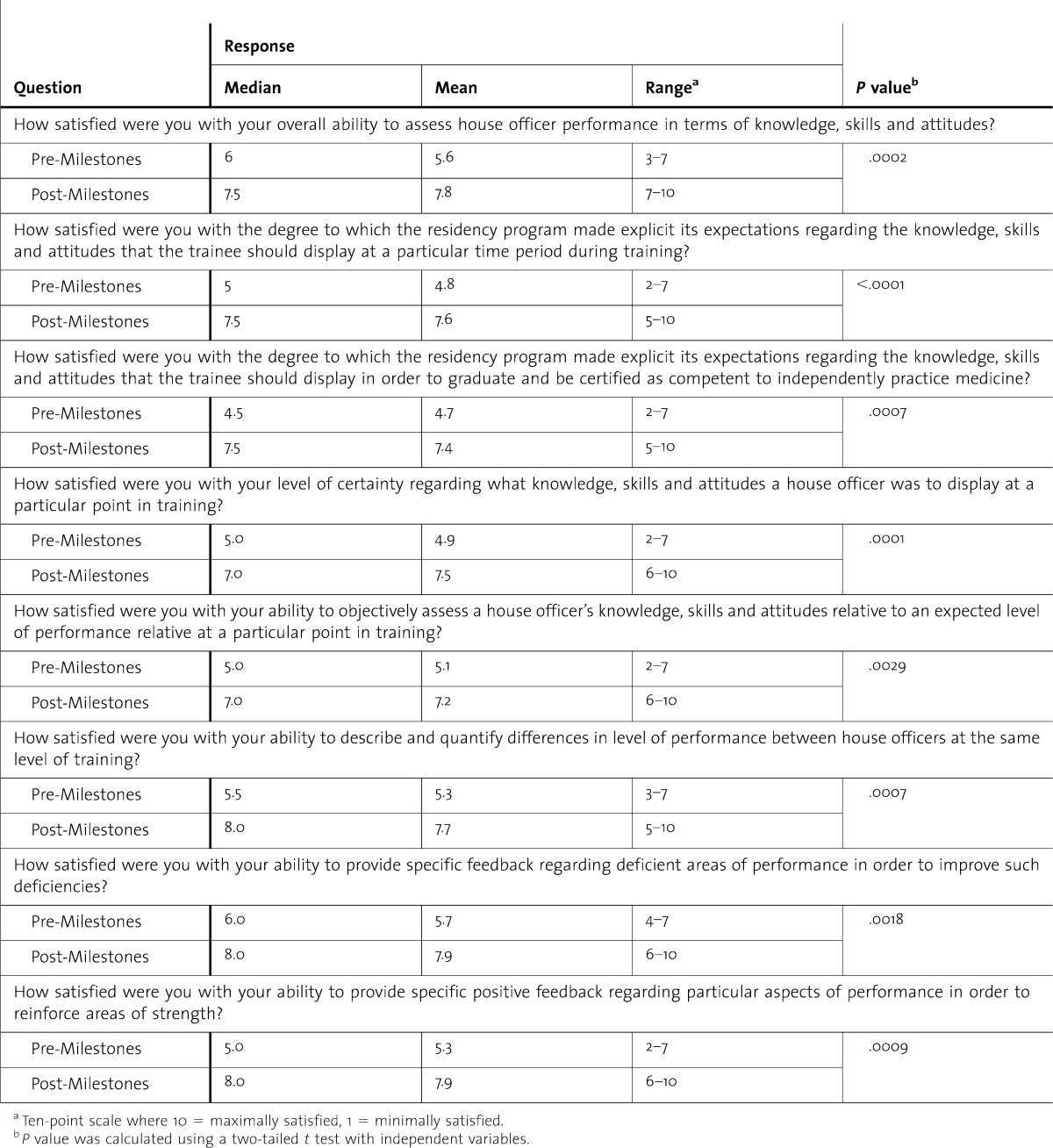

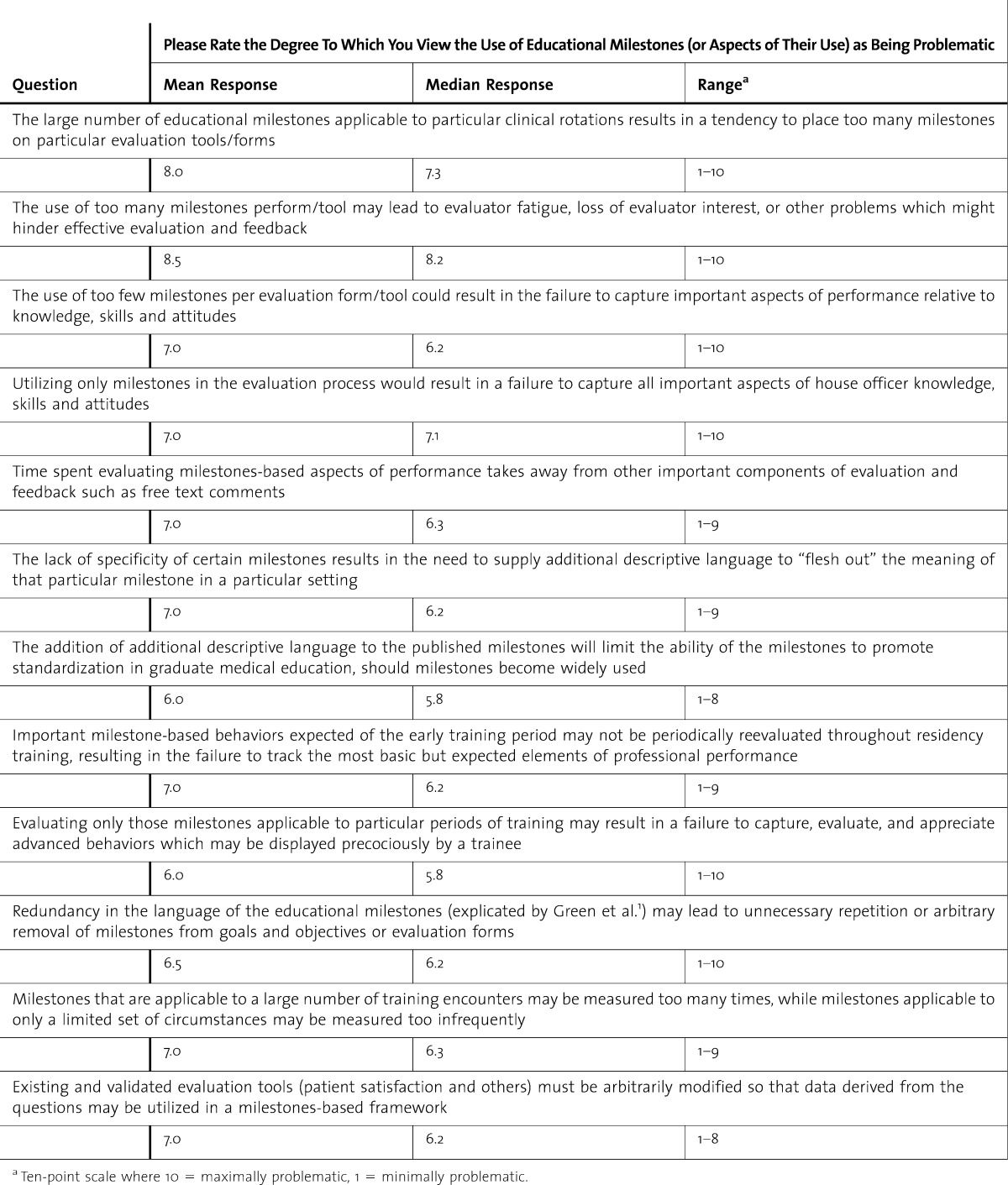

Full-time faculty indicated that milestones significantly improved the evaluation process. When asked, “how satisfied were you with your overall ability to assess house officer performance in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes?” mean satisfaction scores were 5.6 and 7.8 pre-/post-implementation (P = .0002). Faculty rated their ability to “provide specific feedback regarding deficient areas of performance…” at 5.7 and 7.9 pre-/post-implementation, respectively (P = .0018). The faculty's “level of certainty regarding what knowledge, skills and attitudes a house officer was to display at a particular point in training” improved from 4.9 to 7.5 with milestones (P = .0001), and the degree to which the residency program “made explicit its expectations regarding the knowledge and skills that the trainee should display in order to be certified as competent to independently practice medicine” improved from 4.7 to 7.4. (P = .0007) (table 2). While appreciating various benefits of milestones, our faculty nevertheless found certain aspects of the system to be problematic. Using a 10-point rating scale (where 10 was maximally problematic), faculty believed that “the large number of educational milestones applicable to particular clinical rotations results in a tendency to place too many milestones on particular evaluation forms” (mean, 7.5) and that the “the use of too many milestones per form may lead to evaluator fatigue, loss of evaluator interest or other problems which might hinder effective evaluation and feedback” (mean, 8.2). However, they cautioned that the use of too few milestones per evaluation form could result in “the failure to capture important aspects of performance…” (mean, 6.2) (table 3). The use of too many milestones per evaluation form/tool may lead to evaluator fatigue, loss of evaluator interest, or other problems which might hinder effective evaluation and feedback.

table 2.

Faculty Perceptions of Milestones' Effectiveness (n = 12)

table 3.

Faculty Perceptions of Milestones' Challenges (n = 12)

Residents

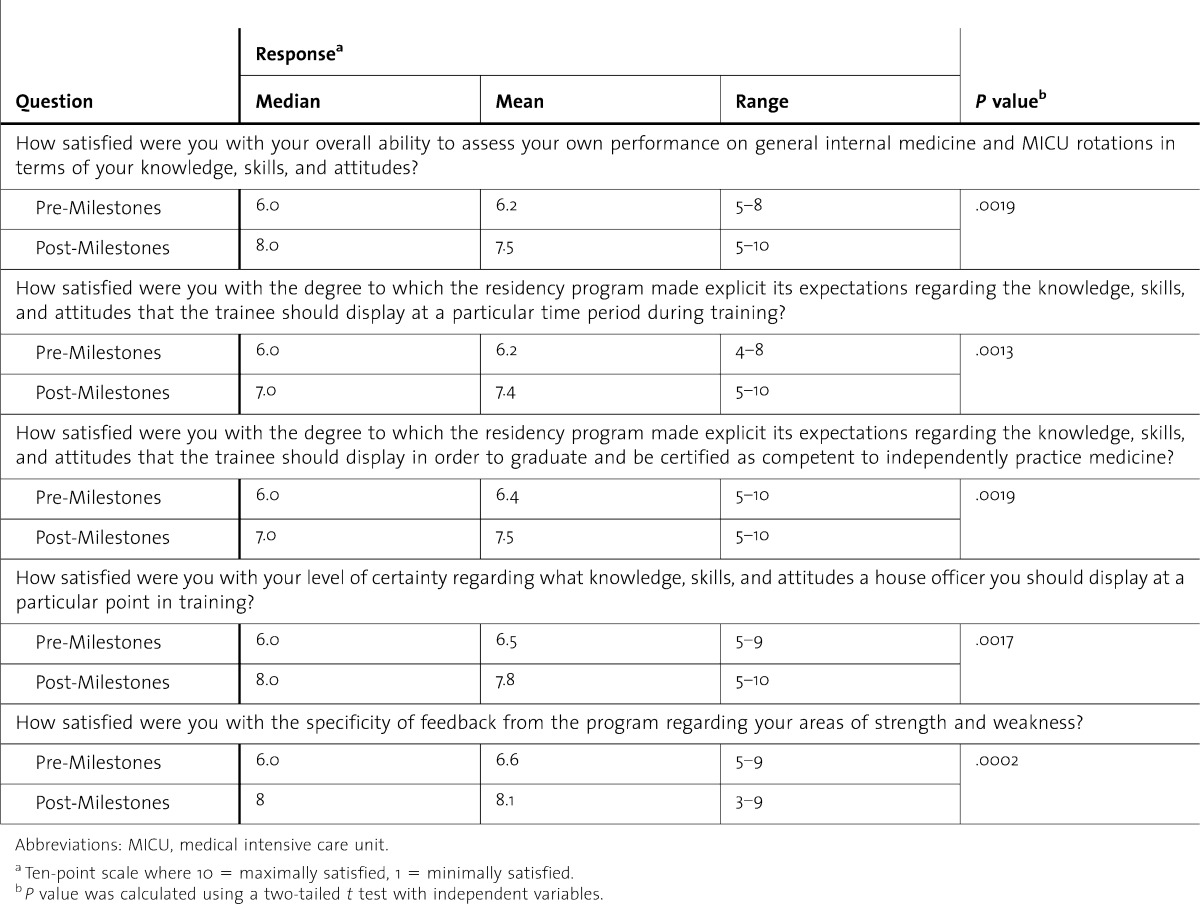

Second- and third-year residents (17 of 26) reported significant pre-/postintervention improvements in the degree to which the program made explicit its performance expectations (P = .0013) in the individual resident's level of certainty regarding what knowledge and skills should be displayed at particular points in training (P = .0017) and in their ability to self-assess on internal medicine rotations (P = .0019). Residents also believed the introduction of milestones led to their receipt of more specific performance feedback (P = .0002) (table 4).

table 4.

Residents' Perceptions of Milestones' Effectiveness (n = 17)

Clinical Competency Committee

Process and Deliberations

Prior to the first clinical competency committee deliberations that followed project implementation in 2010-2011, we held 2 faculty development sessions to explain the new milestones-based evaluation framework. Data were presented at the meetings by having committee members review and discuss resident folder contents in the usual fashion. On overhead monitors, we also displayed relevant milestones-based data that were organized according to the 6 core competency domains, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency domains such as clinical reasoning, and by individual milestones, as needed. This permitted consideration of aspects of individual resident's performance along more general (core competency) or more specific (milestones-based) lines (shown in table 5, online). In this example, the resident was rated more highly on the ACGME clinical reasoning competency and corresponding patient care (PC) milestones (PC-C1 to PC-C4 mean 6.73, n = 31) but was rated lower (P = .008) on the ACGME competency demonstrate compassion and respect to patients (mean 5.68, n = 26) and the related professionalism (P) milestones (P-1 to P-4), particularly P-B3 mean 4.33 (n = 3).

Clinical Competency Committee Survey

Responding clinical competency committee members (7 of 10) agreed somewhat (3 of 7; 43%) or strongly (4 of 7; 57%) that milestones improved the quality of information available for deliberations and agreed somewhat (4 of 7; 57%) or strongly (3 of 7; 43%) that milestones resulted in more uniform promotion standards. Four of 7 respondents (57%) agreed strongly (2 of 7), agreed somewhat (29%), and 1 of 7 disagreed somewhat (14%) that milestones enhanced the ability of the promotions committee to discriminate between specific strengths and weaknesses of individual residents (see table 6, online).

Program Leaders

Surveys

After the introduction of milestones, program leaders believed strongly (2 of 5; 40%) or somewhat (3 of 5; 60%) that the “quality of information useful to program leadership for house staff evaluations had improved”; believed strongly (3 of 4; 75%) or somewhat (1 of 4; 25%) that quality of information necessary to “certify each graduate as capable of independent medical practice had improved; believed strongly (2 of 4; 50%) or somewhat (2 of 4; 50%) that the ability of leaders to specifically identify residents' strengths had improved; and believed strongly (2 of 4; 50%) or somewhat (2 of 4; 50%) that the quality of information necessary to make curricular changes had improved. Comments offered by leaders pointed out that (1) automated milestones-linked low score notices had revealed performance deficits relative to making “appropriate clinical decisions based on the results of common diagnostic testing,” which led to additional teaching sessions on ECG interpretation, as well as one-on-one sessions for select trainees; and (2) that milestones-based mock code performance ratings had led to specific remediation plans for several residents who were soon to lead the code/rapid response team.

Direct Faculty Observation of Performance

A review of the 26 PGY-2 and PGY-3 resident files during the year preceding milestones implementation and during the first 6 months after implementation of milestones indicated that the mean number of faculty direct observation ratings had increased from 3.5 to 12.1 per resident per year (P = .0038).

Discussion

In this study, we successfully implemented milestones on a large scale across multiple settings and rotations, achieving a greater emphasis on direct observation of performance. Faculty and residents perceived that milestones established clear performance expectations, permitted specific performance feedback, and promoted the application of more uniform and fair evaluation standards. Program leaders were able to identify milestones-linked performance deficits on individual and programmatic levels, permitting targeted remediation plans and curricular adjustments. Clinical competency committee members believed that milestones improved the quality of information available for promotions decisions.

Despite legitimate concerns within the educational community5 regarding the ability of evaluators to “measure the [general] competencies” satisfactorily and independent of one another, our initial experience suggests that milestones represent a positive step in this direction. This is consistent with the work by Noel et al.6 that found the use of a more detailed form for the clinical evaluation exercise helped faculty to detect more clinical deficiencies and errors. Huddle et al.5 have pointed out that “assessment of pieces of performance in the fragmentary fashion” cannot necessarily be presumed to add up to the kind of clinical competence desired by the medical community, and the parceling of competencies into more discrete milestones to enhance “measurability” runs this risk. Our experience suggests, however, that this is not an either/or situation, where competencies are too vague and milestones too narrow, but are, if done well, an effective and synergistic “both.”

Milestones selected by our faculty, and as customized to particular scenarios, were useful in guiding direct observations of emerging trainee competence. Similar results obtained in a recently concluded EIP collaborative project in which a Q-sort-selected set of 8 milestones were valuable in guiding outpatient instructors to identify aspects of trainee performance suggesting readiness for “distance supervision.” In the context of high-stakes promotions, our clinical competency committee members and program leaders who possessed a shared understanding of the milestones were able to aggregate and synthesize data gathered from multiple assessments and comments into a determination of whether a trainee had achieved a landmark, consistent with the early work on EPAs.4 Our results therefore imply that concerns relating to measurement of the competencies may be overcome through initial efforts (such as those made at our facility) to develop a shared frame of reference, involvement, and support from faculty. 6–8

Despite the positive attributes of the new system, our study has some limitations, and some challenges remain. Generating situation-specific, time-relevant milestones-based tools through faculty consensus was labor intensive. While we sought to include all potentially relevant milestones on each form, some had to be excluded for practical reasons. Striking an acceptable inclusion/exclusion balance was the most difficult aspect of our implementation. Absent strong faculty support in addressing this and other concerns which arose, our implementation would have been less practical. This may make our work more difficult to replicate in other programs. At the same time, as milestones-based tools and implementation strategies become widely available in anticipation of the NAS, it should soon be possible for programs to adapt these and contribute to learning, developing and sharing best practices.

Conclusions

Educational milestones implemented in our internal medicine program helped to establish clear performance expectations, permitted specific performance feedback and promoted the application of uniform and fair evaluation standards.

Footnotes

All authors from Drs Nabors to Frishman are at the Department of Medicine at New York Medical College at Westchester Medical Center. Christopher Nabors, MD, PhD, is Assistant Professor and Deputy Residency Program Director; Stephen J. Peterson, MD, is a Professor and Executive Vice Chair; Leanne Forman, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Associate Residency Program Director and Director of Adult Primary Care Center; Gary W. Stallings, MD, MPH, is Assistant Professor, Senior Associate Residency Program Director and Director of Third-Year Clerkship; Arif Mumtaz, MD, is Associate Professor and Hospitalist Division Chief; Sachin Sule, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine, Residency Program Director; Tushar Shah, MD, is Assistant Professor, Associate Residency Program Director and Hospitalist; Wilbert Aronow, MD, is Professor of Medicine and Director of Westchester Medical Center Cardiology Clinic; Lawrence DeLorenzo, MD, is Professor of Clinical Medicine, Medical Intensive Care Unit Director and Chairman of Clinical Competency Committee; Dipak Chandy, MD, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Neurology, Pulmonary Critical Care Fellowship Program Director; Stuart G. Lehrman, MD, is Professor of Medicine; William H. Frishman, MD, is Professor and Chairman; Eric Holmboe, MD, is Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer at the American Board of Internal Medicine and American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, Professor Adjunct of Medicine at Yale University, and Adjunct Professor at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

Funding: A grant from the Foundation for Innovations in Medical Education supported expenses related to development and dissemination of milestones-related educational materials. The authors thank the Foundation for Innovations in Medical Education for generously supporting this project. The authors also thank Educational Research Outcomes Collaborative members, particularly Kelly Caverzagie and Lauren B. Meade, who provided invaluable guidance and insights regarding use of educational milestones.

References

- 1.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, Chick DA, Holmboe E, Kane G, Smith CD, et al. Charting the road to competence: developmental milestones for IM residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):5–20. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system–rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Educational Innovation Project. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/140_EIP_PR205.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1176–1177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huddle TS, Heudebert GR. Taking apart the art: the risk of anatomizing clinical competence. Acad Med. 2007;82(6):536–541. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noel GL, Herbers JE, Jr, Caplow MP, Cooper GS, Pangaro LN, Harvey J. How well do internal medicine faculty members evaluate the clinical skills of residents. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(9):757–765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-9-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woehr DJ, Huffcutt AI. Rater training for performance appraisal: a quantitative review. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1994;67(3):189–205. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kogan JR, Conforti L, Bernabeo E, Iobst W, Holmboe E. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04025.x. Opening the black box of clinical skills assessment via observation: A conceptual model. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):1048–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04025.x; 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]