Abstract

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recommends that residents gain broad procedural competence in pediatrics training. There is little recent information regarding practice patterns after graduation.

Objective

We analyzed reported procedures performed in actual practice by graduates of a general pediatrics residency program.

Methods

We conducted an online survey from April 2007 to April 2011 of graduates of a single pediatrics program from a large children's hospital. Eligible participants completed general pediatrics residency training between 1992 and 2006. Graduates were asked about the adequacy of their training for each procedure, as well as the frequency of commonly performed procedures in their practice. As the primary analysis, procedures were divided into emergent and urgent procedures.

Results

Our response rate was 54% (209 of 387). General pediatricians rarely performed emergent procedures, such as endotracheal intubation, intraosseous line placement, thoracostomy, and thoracentesis. Instead, they more commonly performed urgent procedures, such as laceration repair, fracture or dislocation care, bladder catheterization, foreign body removal, and incision and drainage of simple abscesses. Statistically significant differences existed between emergent and urgent procedures (P < .001).

Conclusions

In a single, large, urban, pediatrics residency, 15 years of graduates who practiced general pediatrics after graduation reported they rarely performed emergent procedures, such as endotracheal intubation, but more often performed urgent procedures, such as laceration repair. These results may have implications for ACGME recommendations regarding the amount and type of procedural training required for general pediatrics residents.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument (707.2KB, pdf) used in this study.

What was known

Pediatrics residents must acquire broad procedural competence during their training. Little recent information is available regarding practice patterns after graduation to advise programs on the scope of that training.

What is new

A survey of 15 years of pediatrics graduates from a single program collected self-reported data on adequacy of procedural training and frequency of performance in practice.

Limitations

Survey data were subjective recollections of physicians' practice; the survey instrument was not validated, and the response rate was low.

Bottom line

Pediatrics residency graduates rarely performed emergent procedures, such as endotracheal intubation, but more often performed urgent procedures, such as repairs of lacerations. The results have implications for the amount and type of procedural training for general pediatrics residents.

Introduction

In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) began requiring competency-based assessment by training programs, including broad procedural competence for pediatrics residents.1 For the urban general pediatrician, access to multiple specialties and subspecialties may obviate the need for broad procedural training. Changes in insurance reimbursement may also change the practice of medicine because there may be an incentive to redirect procedures to other providers.

More recently, the approach to competency for complex procedures has been reconsidered, with recognition that uncommonly performed procedures necessitate frequent practice.2–4 Few studies have investigated postgraduation competency, and a recent report by Wood et al5 suggested that current training in newborn resuscitation, for example, may not provide sufficient preparation for those who plan to attend deliveries after graduation.

We sought to determine whether practicing general pediatricians regularly perform procedures common to the emergent and urgent care of children. Incorporating such information into the pediatrics curriculum may improve the preparation of current and future trainees for practice after residency.

Methods

Survey Design

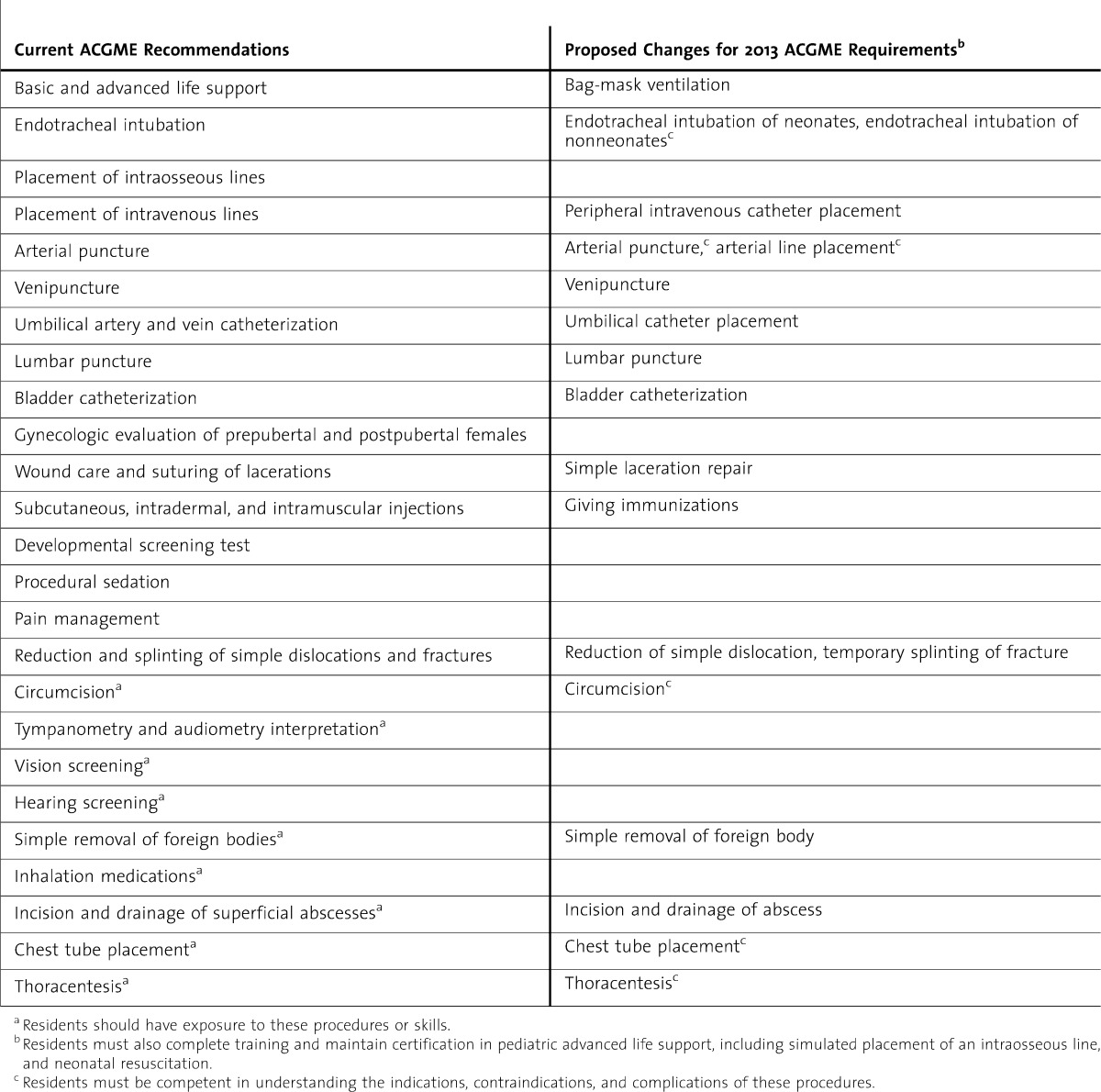

We surveyed graduates to assess their familiarity with procedures required in the ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics (table 1).1 Questions focused on 2 basic concepts: (1) were residents adequately trained in the procedure during residency; and (2) how frequently did they perform the procedure in their current practice.

TABLE 1.

Setting and Participants

We conducted the survey at a single, large, primary and tertiary care, teaching hospital. Pediatrics residents at this hospital have diverse primary care experience, as well as required rotations in critical care subspecialties. Eligible participants included pediatrics graduates who graduated between 1992 and 2006 and were actively practicing ambulatory pediatrics. Graduates practicing in other subspecialties, those practicing transport or hospitalist medicine or those no longer practicing general pediatrics, were excluded from this analysis. A request to complete an online survey (provided as online supplemental material) was mailed to all graduates.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the performance of 4 emergent and 4 urgent procedures as groups. We categorized procedures as emergent if performing them immediately could prevent life-threatening adverse events (endotracheal intubation, intraosseous line placement, thoracostomy, and thoracentesis) and as urgent if the procedure required immediate management (laceration repair with sutures, laceration repair with tissue adhesive, reduction/splinting of simple dislocations and fractures, incision and drainage of superficial abscesses). The individual procedure data were combined into an emergent group and an urgent group. Each group represents the cumulative responses for the combined procedures. Therefore, each respondent may have up to 4 responses per group. If no response was given for individual questions, the remainder of the responses was still included in data analysis. If different responses were made to the same question, the responses to this question were removed.

The Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was conducted to examine whether there was a statistically significant difference in ordinal frequency between emergent and urgent groups. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 15 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the hospital.

Results

Our response rate was 54% (209 of 387). According to our exclusion criteria, we excluded 84 respondents from the analysis (73 graduates practicing subspecialty pediatrics, 8 who were hospitalists, and 3 who practiced transport medicine). Of the 125 general pediatrician respondents, 109 (87%) provided procedural data to analyze. We excluded 16 respondents (13%) for not completing the procedural section of the survey (n = 13) and who were not practicing clinical medicine (n = 3).

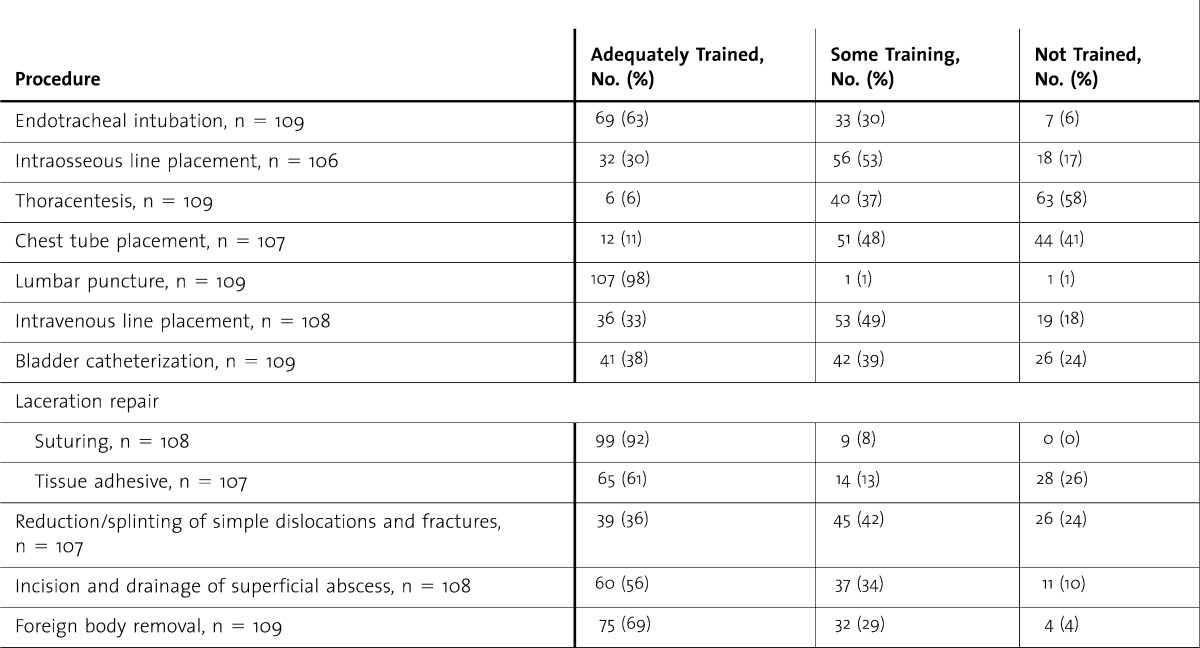

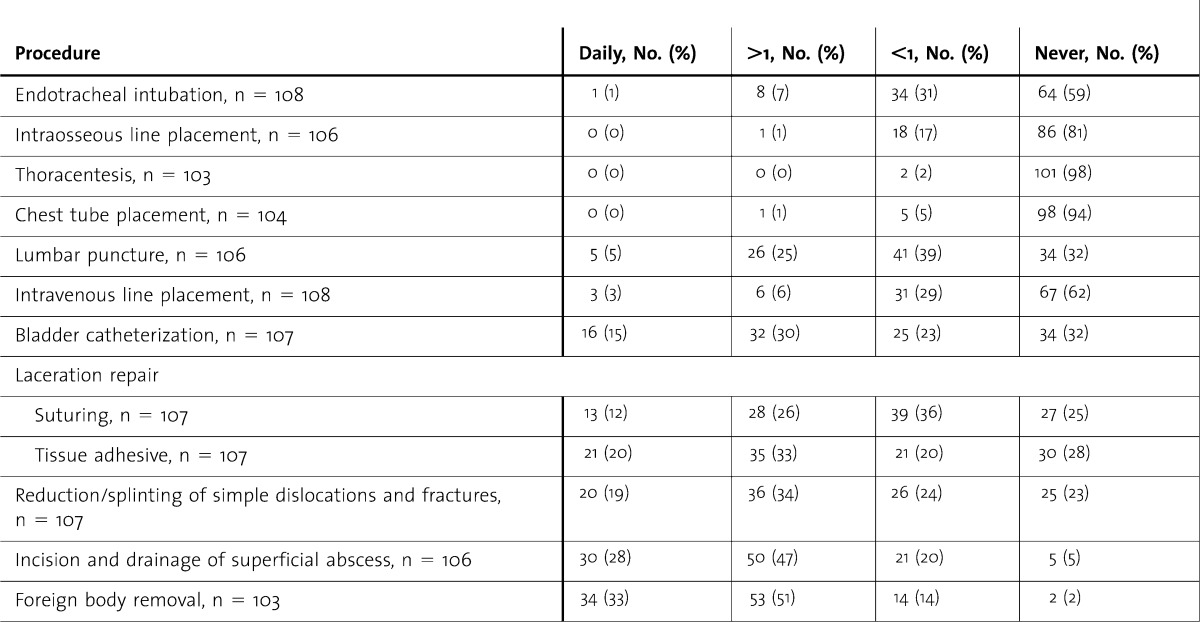

Respondents indicated that some procedures were nearly universally trained or not trained, whereas training for some procedures appeared more divergent (table 2). The 4 emergent procedures were infrequently performed, whereas general pediatricians performed the urgent procedures more frequently (table 3). For many of the procedures, frequency of procedures appeared to be related to adequacy of training (laceration repair, incision and drainage, foreign body removal). When comparing emergent versus urgent procedures combined as groups, urgent procedures were more commonly performed than were emergent procedures (P < .001).

table 2.

Adequacy of Training During Residency

table 3.

Frequency of Occurrence

For lumbar puncture (LP), most respondents (107 of 109, 98%) reported adequate training, but only 5 (5%) respondents reported performing LP routinely, 26 (25%) reported performing LP more often than once per year, 41 (39%) reported performing LP less than once per year, and 34 (32%) reported never performing the procedure. Similarly, for endotracheal intubation, 69 of 109 (63%) respondents reported adequate training and 33 of 109 (30%) reported some training; but endotracheal intubation was reported as routine for only 1 respondent. For incision and drainage of superficial abscesses, 97 respondents (90%) reported some or adequate training (11 [10%] reported no training), but 101 (95%) respondents reported having performed the procedure at some point after graduation (5 [5%] reported never performing the procedure).

Discussion

General pediatricians performed some procedures more commonly than they did others in their pediatric practice but infrequently performed emergent procedures, such as endotracheal intubation, intraosseous line placement, and thoracostomy and thoracentesis. Urgent procedures, such as fracture care, laceration repair, incision and drainage of abscesses, foreign body removal, and bladder catheterization, were commonly performed procedures.

A 1991 survey conducted by the American Board of Pediatrics described procedures that general pediatricians thought were necessary for pediatric training.6 Eighty percent of respondents (2885 of 3606) cited 49 procedures as necessary for training, including endotracheal intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and arterial puncture. Also included in this list were procedures that are no longer routinely performed, such as gastric gavage, mist tent vaporizer, and aspiration of the bladder.

In 2007, the Residency Review Committee (RRC) for Pediatrics published a list of 16 procedures and skills in which all residents must have “sufficient” training (table 1).1 Based on these requirements and additional recommended procedures, Gaies et al7 surveyed the opinions of residency program directors regarding the importance of these procedures and residents' perceived competency. Notably, a large percentage of program directors did not assign the same level of importance as the RRC did for its recommended procedures. Additionally, the program directors' assessments of their own residents' competencies were also lower than the RRC goal. Of note, the ACGME8 has proposed a revision of these recommendations beginning in 2013. Table 1 includes the proposed changes.

Our survey of procedures performed by graduates of a single, large, pediatrics training program, including 15 years of graduates, is the largest and most comprehensive study addressing the performance of pediatrics procedures in actual clinical practice, to our knowledge. An assessment of family medicine graduates in Canada reported their procedural practice standards vary.9 Simon and Sullivan10 have assessed pediatric procedural competency for community emergency practitioners, but no work has been done to assess the utility of procedural training for the general pediatrician.

Adequacy of training may have affected the frequency of procedures. As shown in tables 2 and 3, responses to adequacy of training were better for urgent procedures than they were for emergent procedures, and urgent procedures were more commonly performed. A corollary observation is that inadequate training in emergent procedures may have led to infrequent performance of emergent procedures. However, some nonemergent procedures, such as intravenous line placement, also follow the trend of inadequate training and infrequent performance. Infrequent performance may be related to uncommon practice in the routine practice of general pediatricians (eg, LP, endotracheal intubation) or it may be due to inadequate training. As noted in the case of incision and drainage, more respondents reported performing this procedure than reported training for this procedure.

Our study had several limitations. First, our data are based on the subjective recollection of physicians' practice, so the actual frequency of the procedures may not be as accurate as in a prospective study. Second, respondents' interpretation of the study questions may have varied. Third, our survey instrument was developed internally using the ACGME procedures and frequencies determined by informal polling of a sample of graduates and is not validated. Fourth, we obtained a low response rate. Finally, the availability of other physicians or ancillary staff to perform the procedure is also unknown.

Conclusions

Procedural training is an important component of general pediatrics training. Urgent procedures are commonly performed, but emergent procedures are rarely performed. The results of our study may have implications for ACGME recommendations regarding type of procedures required in pediatrics training.

Footnotes

All authors are at Children's Hospital Los Angeles and Keck School of Medicineat the University of Southern California, Los Angeles; Eyal Ben-Isaac, MD, is Director of Pediatric Residency and Associate Professor of Clinical Pediatrics; Matthew Keefer, MD, is Assistant Director of Pediatric Residency and an Assistant Professor of Clinical Pediatrics; Michelle Thompson, MD, is Associate Director of Pediatric Residency and Assistant Professor of Clinical Pediatrics; and Vincent J. Wang, MD, MHA, is Associate Division Head of Emergency Medicine and Associate Professor of Clinical Pediatrics. Drs Ben-Isaac, Keefer, and Thompson are in the Division of General Pediatrics, Dr Wang is in the Division of Emergency Medicine.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Statistical analysis was performed by Phung Pham, MS, Research Associate of the Division of Emergency Medicine, Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

References

- 1.[ACGME] Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/320_pediatrics_07012007.pdf. Effective July 1, 2007. Accessed December 5, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaies MG, Morris SA, Hafler JP, Graham AJ, Zhou J, Landrigan CP, et al. Reforming procedural skills training for pediatric residents: a randomized, interventional trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):610–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sznajder JI, Zveibil FR, Bitterman H, Weiner P, Bursztein S. Central vein catheterization: failure and complication rates by three percutaneous approaches. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146(2):259–261. doi: 10.1001/archinte.146.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niles D, Sutton RM, Donoghue A, Kalsi MS, Roberts K, Boyle L, et al. “Rolling Refreshers”: a novel approach to maintain CPR psychomotor skill competence. Resuscitation. 2009;80(8):909–912. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood AM, Jones MD, Jr, Wood JH, Pan Z, Parker TA. Neonatal resuscitation skills among pediatricians and family physicians: is residency training preparing for postresidency practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(4):475–480. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00234.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver TK, Jr, Butzin DW, Guerin RO, Brownlee RC. Technical skills required in general pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1991;88(4):670–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaies MG, Landrigan CP, Hafler JP, Sandora TJ. Assessing procedural skills training in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):715–722. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.[ACGME] Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatrics. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/320_pediatrics_07012013.pdf. Approved September 30, 2012. Effective July 1, 2013. Accessed on December 8, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaytors RG, Szafran O, Crutcher RA. Rural-urban and gender differences in procedures performed by family practice residency graduates. Fam Med. 2001;33(10):766–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon HK, Sullivan F. Confidence in performance of pediatric emergency medicine procedures by community emergency practitioners. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1996;12(5):336–339. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]