Abstract

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) patients have disturbed sleep patterns which may lead to altered circadian rhythm in serum cortisol secretion. The aim of this study was to assess circadian changes, if any, in serum cortisol levels in female patients with FMS. Cortisol levels were estimated every 6 h during 24 h period; in 40 female patients satisfying ACR criteria for FMS (Age 36.4 ± 9.9), and 40 healthy females without FMS (Age 33.8 ± 11.1). A significant difference in the night time serum cortisol level was observed among the patients and control groups (patients, 12.9 ± 9.7 controls 5.8 ± 3.0; p < 0.01). However, no significant difference was found in serum cortisol levels in patients and control groups in the morning (patients, 28.4 ± 13.2 controls, 27.6 ± 14.5; p > 0.05), afternoon (patients, 14.4 ± 5.6 controls, 14.0 ± 6.6; p > 0.05) and evening hours (patients, 10.9 ± 5.8 controls, 8.9 ± 3.6; p > 0.05). It could be concluded that there is an abnormality in circadian secretion of cortisol in female FMS patients.

Keywords: Fibromyalgia syndrome, Cortisol, Circadian rhythm, American College of Rheumatology Criteria

Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a common chronic musculoskeletal disorder characterized by poor sleep, unrelenting fatigue and diffuse muscle pain, which occurs for more than 3 months along with the presence of 11 out of 18 tender points [1]. It has a substantial negative impact on patients’ life [2] occurring more often in women than in men, with an estimated prevalence of 2 to 4 % in the general population and a ratio of 3.5 % of women for 0.5 % of men [3]. The symptoms associated with FMS (difficulty sleeping, fatigue, malaise, myalgias, gastrointestinal complaints, and decreased cognitive function) are similar to those observed in individuals whose circadian pacemaker is abnormally aligned with their sleep-wake schedule.

Cortisol normally follows a circadian pattern of secretion, peaking 30 min after waking as there is a gradual decrease in serum cortisol level throughout the day time reaching minimum around midnight [4, 5]. However, studies on FMS patients have reported increased daytime plasma or salivary cortisol levels [6–9]. Moreover, in a recent study by Riva et al. [10] it was reported that patients with FMS had significantly lower cortisol levels during the day which gets most pronounced in the morning whereas Wingenfeld et al. [11] reported a normal cortisol and adeno-cortico-tropic hormone (ACTH) levels in FMS patients compared with controls. There is currently no consensus as to the overall state of cortisol activity in FMS.

One of the study reported by McLean et al. [12] suggested that there were no significant difference in cortisol levels or diurnal cortisol variation between FMS patients and healthy controls. However, they also reported pain symptoms early in the day among women with FMS are associated with variations in function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The similarity in symptoms between patients with FMS and individuals with misaligned circadian phase as well as the observation of cortisol levels being tightly regulated by the circadian pacemaker raises the possibility that there may be an abnormality of circadian pattern of cortisol secretion in patients with FMS. Therefore, on the basis of above reports we planned to study the circadian pattern of serum cortisol in patients with FMS and in healthy subjects. Moreover, as the pituitary–adrenal hormones are secreted in a pulsatile manner, with both circadian and ultradian rhythmicity, we employed a technique of discrete blood sampling across the 24 h hormonal cycle to characterize circadian cortisol secretion.

Materials and Methods

The study group comprised of 40 females with FMS (Mean age 36.4 ± 9.9, BMI 25.9 ± 4.0) and control group comprised of 40 age matched healthy females without FMS (Mean age 33.8 ± 11.1, BMI 24.0 ± 3.5), who were non-alcoholic, non-smokers, non-diabetic without any kind of cardiac, respiratory and endocrinal disease. Subjects were excluded if they met criteria for rheumatoid arthritis and psychiatric disorders. Patients of FMS were recruited from the Department of Rheumatology, at the King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India. Diagnosis of FMS was made using 1990 American College of Rheumatology Criteria. Control subjects were recruited from relatives of the patients and other locations of Lucknow.

All the patients and controls were screened to exclude any recent Chronobiological disruptions, such as shift work or travel across various time zones. Before enrolling in the study, written informed consent was obtained from both the subject groups using documents approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this study. All data was coded to remove any identifiable information. Both the groups of patients and controls were admitted to the Department of Rheumatology, where the subjects completed a structured questionnaire, which assessed the biographical information, medical, personal and family history. Quality of life was assessed using fibromyalgia impact questionnaire revised (FIQR) (a patient self-reported instrument that assesses the impact of fibromyalgia symptoms and functional impairment, where patients were required to indicate a score between range of 0–10, with 10 indicating very severe) [13].

Sample Collection

Four milliliters of intravenous blood was collected at 6 am, 12 noon, 6 pm and 12 mid night. Blood samples were spun at 3,000 rpm for 10 min; all the samples collected were spun within half an hour of the collection, serum was separated and was aliquoted into labeled storage tubes and frozen at −40 °C until assayed. Evening and night time samples were kept at 40 °C and were processed next morning. Cortisol was assayed by ELISA Kit.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the INSTAT 3.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA) [14]. Quantitative variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Welch’s corrected unpaired t test was performed to assess the difference in biochemical parameters among the two groups and the association between clinical characteristics among patients and control group was expressed by Fisher’s exact test which was used to obtain the odds ratio (OR) with 95 % confidence interval (95 % Cl). All Statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was chosen as the level of significance.

Results

Subject characteristics for women with FMS in the study and control group are detailed in Table 1. Muscle twitching, lack of energy, morning tiredness, night tiredness, disturbed sleep, morning stiffness, morning fatigue, headache, disequilibrium in climbing stairs and anxiety were more commonly seen in patients with FMS than in the control group. However, no significant differences were found in weight loss, jaw pain, abdomen pain and fever (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics among study and control groups

| Parameters (SI) | Study = 40 (mean ± SD) | Controls = 40 (mean ± SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.4 ± 9.9 | 33.8 ± 11.1 | >0.05 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (body mass index) | 25.9 ± 4.0 | 24.0 ± 3.5 | <0.05 |

| ESR (erythrocytes sedimentation rate) | 26.5 ± 9.9 | 25.1 ± 8.6 | >0.05 |

| SGPT (serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase) | 42.0 ± 13.4 | 4.0 ± 13.8 | >0.05 |

| FIQR (fibromyalgia impact questionnaire revised) | 93.3 ± 4.7 | 6.2 ± 8.8 | <0.01 |

| TPC (Tender points count) | 16.9 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 2.4 | <0.01 |

Study group = females with fibromyalgia syndrome, control group = females without fibromyalgia syndrome

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of women with FMS and control women

| Parameters | Patients n = 40 (%) | Controls n = 40 (%) | Odds ratio | 95 % Confidence interval | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle twitching | 40 (100) | 7 (17.5) | 361.8 | 19.91–6,574.0 | <0.01 |

| Lack of energy | 39 (97.5) | 8 (20) | 156.0 | 18.515–1,314.4 | <0.01 |

| Morning tiredness | 33 (82.5) | 6 (15) | 26.7 | 8.117–87.93 | <0.01 |

| Night tiredness | 30 (75) | 11 (27.5) | 7.9 | 2.918–21.43 | <0.01 |

| Disturbed sleep | 38 (95) | 1 (2.08) | 741.0 | 64.43–8,520.9 | <0.01 |

| Weight loss | 14 (35) | 7 (17.5) | 2.5 | 0.9845–7.203 | >0.05 |

| Morning stiffness | 38 (95) | 3 (7.5) | 234.3 | 36.99–1,484.4 | <0.01 |

| Morning fatigue | 39 (97.5) | 5 (12.5) | 273.0 | 30.385–2,452.9 | <0.01 |

| Headache | 37 (92.5) | 21 (52.5) | 11.1 | 2.950–42.214 | <0.01 |

| Disequilibrium in climbing stairs | 32 (80) | 3 (7.5) | 49.3 | 12.055–201.88 | <0.01 |

| Jaw pain | 11 (27.5) | 7 (17.5) | 1.7 | 0.612–5.216 | >0.05 |

| Abdominal pain | 23 (57.5) | 19 (47.5) | 1.4 | 0.6188–3.614 | >0.05 |

| Fever | 12 (30) | 15 (37.5) | 0.7 | 0.2814–1.813 | >0.05 |

| Anxious | 37 (92.5) | 15 (37.5) | 20.5 | 5.384–78.484 | <0.01 |

The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire revised score (FIQR) (patients, 93.3 ± 4.7 controls 6.2 ± 8.8; p < 0.01) and Tender Points Count (TPC) (patients 16.9 ± 1.6; controls 2.3 ± 2.4; p < 0.01) was significantly higher in women with FMS than in controls. All the patients had normal laboratory tests regarding erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) (Table 1).

Circadian Rhythm in Serum Cortisol

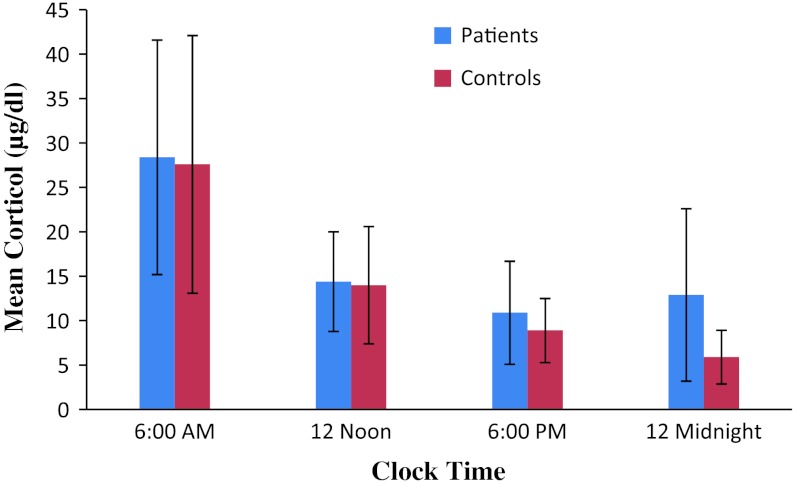

A significant difference in the night time serum cortisol level was observed among the patients and control groups (patients 12.9 ± 9.7; controls 5.8 ± 3.0; p < 0.01). However, serum cortisol was not found significantly different between patients and control groups in the morning hours (patients 28.4 ± 13.2; controls, 27.6 ± 14.5; p > 0.05), whereas no significant differences were found in the afternoon (patients 14.4 ± 5.6; controls 14.0 ± 6.6; p > 0.05) and evening time (patients 10.9 ± 5.8; controls 8.9 ± 3.6; p > 0.05) (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

Cortisol patterns in different time intervals of the day

Discussion

This study was designed to examine the hypothesis that female patients with FMS exhibit alterations in circadian rhythm of serum cortisol secretion. Although, the serum cortisol levels in patients with FMS have been studied extensively, however, to the best of our knowledge there are no previous reports on its circadian nature in women with FMS. The basis for selecting only women in this study was the high prevalence of FMS in females as compared to males [15]. In this study we found, a significant difference in the mid-night level of serum cortisol in patients compared to control group, which revealed a disrupted circadian pattern in serum cortisol level in patients with FMS. However, we found no abnormalities in serum cortisol level in the morning, afternoon and evening time. A normal circadian cortisol pattern is one in which there is a rise before waking (before 7–8 am), and then a gradual decline throughout the rest of the day [4, 16, 17]. However, in FMS patients this normal circadian pattern was found deranged. Due to the circadian nature of cortisol secretion, identification of cortisol dysregulation may not appear if total cortisol levels are measured at a single time point. Therefore, we have measured the cortisol levels at four time points during a day.

Our findings of altered level of serum cortisol at night agrees with Crofford et al. [7] report of disturbed level of night cortisol level and on the other hand it differs from the study of Klerman et al. [18], who found no difference in the circadian variation of cortisol in patients with FMS. Moreover, results of our study did not match with the findings of Nees [19] and Izquierdo et al. [20], who reported decreased cortisol levels in FMS patients. However, this discrepancy cannot be explained except to note our use of a substantially larger sample size and repeated measures of serum cortisol over time within patients and control groups.

There have been reports of moderate to severe fatigue in FMS patients, [21, 22] however, we report a significant difference in morning fatigue and pain in patients with FMS than in control population. Morning stiffness, headache, anxious and other symptoms of FMS were increased in patients group, but showed no circadian pattern in either study group. These findings suggest that the abnormalities in circadian phase do not account for the reported abnormalities in the symptoms of fatigue, sleep disturbances, pain etc. that occur in patients with FMS.

The aim of this study was to assess the circadian rhythm disturbances in serum cortisol level in female patients with FMS. It is proved that female patients with FMS exhibit alterations in circadian rhythm of serum cortisol secretion. This increase in nocturnal serum cortisol in patients group suggests dysregulated circadian patterns which may explain in part the patient complaint of unrefreshing sleep. However, the findings of the present study may be a very small step put forward. Further studies are necessary to confirm, evaluate and replicate this study in a larger sample size with different ethnicities.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

None.

Refrences

- 1.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Albeles M, Clark P, Fam AG, Farber SJ, Fiechtner JJ, Franklin CM, Gatter RA, Hamaty D, Lessard J, Lichtbroun AS, Masi AT. The American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, Burgess SM, Palmer SC, Abetz L, Martin SA. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belgrand L, So A. Fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Rev Med Suisse. 2011;16:604–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallerius S, Rosmond R, Ljung T, Holm G, Bjorntorp P. Rise in morning saliva cortisol is associated with abdominal obesity in men: a preliminary report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:616–619. doi: 10.1007/BF03347017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer ME. Stress, glucocorticoids and ageing of the immune system. Stress. 2005;8:69–83. doi: 10.1080/10253890500100240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catley D, Kaell AT, Kirschbaum C, Stone AA. A naturalistic evaluation of cortisol secretion in persons with fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:51–61. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)13:1<51::AID-ART8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crofford LJ, Pillemer SR, Kalogeras KT. Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis perturbations in patients with Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1583–1592. doi: 10.1002/art.1780371105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griep EN, Boersma JW, Lentjes EG, Prins AP, ven der Korst JK, de Kloet ER. Function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in patients with fibromyalgia and low backpain. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1374–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCain GA, Tilbe KS. Diurnal hormone variation in fibromyalgia syndrome: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1989;16(Suppl. 19):154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riva R, Mork PJ, Westgaard RH, Lundberg U. Fibromyalgia syndrome is associated with hypocortisolism. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17:223–233. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wingenfeld K, Heim C, Schmidt I, Wagner D, Meinlschmidt G, Hellhammer DH. HPA axis reactivity and lymphocyte glucocorticoid sensitivity in fibromyalgia syndrome and chronic pelvic pain. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:65–72. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815ff3ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mclean SA, Williams DA, Harris RE, Kop WJ, Groner KH, Ambrose K. Momentary relationship between cortisol secretion and symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3660–3669. doi: 10.1002/art.21372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, Ward R, Han BK, Ross RL. The revised Fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(4):120. doi: 10.1186/ar2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wass John. Software: statistics, fast and easy. Science. 1998;282(5394):1652. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartels EM, Dreyer L, Jacobsen S, Jespersen A, Bliddal H, Danneskiold SB. Fibromyalgia, diagnosis and prevalence. Are gender differences explainable? Ugeskr Laeger. 2009;171:3588–3592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenspan FS. The thyroid gland. In: Gardner DG editor. Basic & clinical endocrinology. 7th ed. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2004. p. 215–251.

- 17.Bauer ME. Stress, glucocorticoids and ageing of the immune system. J Stress. 2005;8:69–83. doi: 10.1080/10253890500100240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klerman EB, Goldenberg DL, Brown EN, Maliszewski AM, Adler GK. Circadian rhythms of women with fibromyalgia. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1034–1039. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.3.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nees F, Rüddel H, Mussgay L, Kuehl LK, Römer S, Schächinger H. Alteration of delay and trace eye blink conditioning in fibromyalgia patients. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:412–418. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d2bbef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izquierdo Alvarez S, Bancalero Flores JL, García Pérez MC, Serrano Ostariz E, Alegre deMiquel C, Bocos Terraz JP. Evaluation of urinary cortisol levels in women with fibromyalgia. Med Clin (Barc). 2009;133(7):255–257. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldenberg DL, Simms RW, Geiger A, Komaroff AL. High frequency of fibromyalgia inpatients with chronic fatigue seen in a primary care practice. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:381–387. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1407–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]