Abstract

Background

Calcaneal lengthening has been used to correct planovalgus foot deformities in patients with cerebral palsy (CP).

Questions/purposes

This study was performed to investigate the amount of correction that can be achieved after calcaneal lengthening for the treatment of a planovalgus deformity in patients with CP and to provide cutoff values based on the preoperative radiographic measurements that suggest additional procedures to achieve satisfactory correction.

Methods

Seventy-five consecutive patients with CP who underwent calcaneal lengthening for planovalgus deformity were included. Radiographic indices were measured on preoperative and latest followup weightbearing foot radiographs. The cutoff values of the preoperative radiographic measurements between the corrected and undercorrected groups were analyzed. The cutoff values are the reference values that can judge the possibilities of sufficient correction of a planovalgus deformity by calcaneal lengthening.

Results

The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 11.0 ± 5.2 years and the minimum followup was 1.0 years (mean, 3.1 ± 2.2 years; range, 1.0–8.4 years). AP talus-first metatarsal angle, calcaneal pitch angle, talocalcaneal angle, lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and naviculocuboid overlap showed major improvements after calcaneal lengthening. The cutoff values of preoperative measurements between the corrected and undercorrected groups were 23° AP talus-first metatarsal angle, 36° lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and 72% naviculocuboid overlap.

Conclusions

Calcaneal lengthening with concomitant peroneus brevis lengthening is an effective procedure for correcting a planovalgus foot deformity in patients with CP. However, for patients with greater than 23° AP talus-first metatarsal angle, 36° lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and 72% naviculocuboid overlap, additional procedures for medial stabilization, such as tibialis posterior tendon reefing and talonavicular arthrodesis, should be considered as a result of the possibility of undercorrection with calcaneal lengthening alone.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See the Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

A planovalgus foot deformity is common in patients with cerebral palsy (CP). This deformity is most likely a consequence of muscle imbalance and abnormal forces on a skeletally immature foot. It frequently leads to pain while weightbearing, callus formation, or an ulcerative lesion as a result of the prominent talar head and gait disturbances resulting from nonreducible talonavicular joint subluxation [10, 16]. Many surgical options such as medial displacement osteotomy of the calcaneus, subtalar extraarticular arthrodesis, lengthening of the lateral column, and triple arthrodesis have been suggested [10–12, 16, 17, 23]. Of these, calcaneal lengthening osteotomy has been used most commonly to correct the deformity and not sacrifice joint motion in patients with CP.

Calcaneal lengthening for symptomatic idiopathic planovalgus deformity in children and adolescents was introduced by Evans in 1975 [10]. Subsequently, numerous studies have reported the success of calcaneal lengthening for treatment of symptomatic flatfoot deformity in patients with CP [1, 2, 5, 9, 18–20, 22, 28, 29]. Some authors reported a 25% recurrence rate after calcaneal lengthening and other major limitations to this procedure in patients with CP [2, 9]. Additional procedures such as a medial soft tissue procedure, medial bony procedure, or triple arthrodesis could be performed concomitantly with calcaneal lengthening, which depends on severity of the deformity. However, there has been no guideline to determine the necessity of these procedures considering the radiographic indices. Furthermore, because of the difficulty to properly judge during surgery, it would be helpful to develop indications based on specific radiographic parameters regarding the necessity for these procedures from preoperative weightbearing radiographs. It is possible that cutoff values measured on these preoperative radiographs suggesting the need for these additional procedures can be determined by comparing the corrected and undercorrected groups of patients.

Therefore, this study was performed to investigate the amount of correction that can be achieved after calcaneal lengthening for treatment of a planovalgus foot deformity in patients with CP and to provide cutoff values based on the specific preoperative radiographic measurements that suggest when procedures in addition to calcaneal lengthening are needed to achieve a satisfactory correction.

Patients and Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board at our institution. The inclusion criteria were: (1) consecutive patients with CP who underwent calcaneal lengthening for planovalgus foot deformity since 2003; (2) patients who had preoperative and postoperative weightbearing AP and lateral foot radiographs; and (3) patients with a minimum followup of 1 year. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who had concomitant medial column procedures with calcaneal lengthening; (2) patients with a history of foot surgery; or (3) patients with inadequate foot radiographs for measurement. Age, sex, geographic type, and details of concomitant surgery were obtained from a review of the patients’ medical records. A total of 103 patients with CP were followed for more than 1 year after calcaneal lengthening since 2003. Nineteen patients were excluded as a result of inadequate foot radiographs and nine patients who had medial column procedures also were excluded. Thus, a total of 75 consecutive patients with CP were enrolled in this study. There were 51 male and 24 female patients. The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 11 ± 5 years (range, 5–30 years) and the minimum duration of followup was 1 year (mean, 3 ± 2 years; range 1–8 years) (Table 1). Sixty-five feet (87%) had tendo-Achilles lengthening or a Strayer procedure concomitantly with the calcaneal lengthening or previously, and in the remaining 10 feet, this procedure was not performed.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and surgical procedures

| Patients’ and surgical information | Number |

|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 51/24 |

| Age (years) | 11.0 ± 5.2 (range, 5.4–30.1) |

| Geographic type (hemiplegia/diplegia/triplegia/quadriplegia) | 5/48/3/19 |

| Followup (years) | 3.1 ± 2.2 (range, 1.0–8.4) |

| Calcaneal lengthening (bilateral/unilateral) | 54/21 |

| Number of surgical procedures per patient | 6.7 ± 3.0 (range, 2–14) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Calcaneal lengthening was performed as one of the single-event multilevel surgeries, to improve the gait pattern, by two pediatric orthopaedic surgeons (CYC, MSP) with the same philosophy toward treatment. The surgical procedure used was a minor modification of the Evans technique [10]. Transverse osteotomy was performed using an oscillating saw between the anterior and the middle facets of the calcaneus 1.5 cm proximal to the calcaneocuboid joint. The osteotomy surfaces of the proximal and distal calcaneal fragments were widened by a laminar spreader until anatomic reduction of the subtalar and talonavicular joints was achieved under fluoroscopic guidance. A commercially available human iliac crest allograft bone wedge was trimmed into a trapezoidal shape and matched in size to fit the osteotomy site, which then was inserted in the distracted area. Stabilization of the bone graft or calcaneocuboid joint was not performed. The peroneus brevis tendon was lengthened by Z-plasty, but the peroneus longus tendon was not lengthened. The tendoAchilles lengthening or Strayer procedure was performed, concomitantly, in patients with equinus deformity. After the surgery, each patient received postsurgical care as follows. All patients were immobilized wearing a short leg cast and had a nonweightbearing period of 5 to 6 weeks after the surgery. Standing and weightbearing were resumed with a leaf spring-type ankle-foot orthosis, which was worn for 3 months. Subsequently, patients were referred to a local rehabilitation center to continue muscle-strengthening exercises and gait training.

A consensus-building session to select and define the radiographic parameters was held by five orthopaedic surgeons (MSP, KML, KHS, SGS, BA), who had orthopaedic experience of 13, 11, 9, 4, and 2 years, respectively. Previous studies were reviewed [3, 6, 13, 24–27], and five parameters that were considered to have clinical relevance in quantifying planovalgus foot deformity were selected for the radiographic measurements. Additionally, two indices were developed to evaluate the relative calcaneal length and calcaneocuboid subluxation after calcaneal lengthening osteotomy. Seven items finally were selected for the radiographic measurements.

The radiographic evaluation included weightbearing AP and lateral foot radiographs. The foot radiographs were taken using a UT 2000 X-ray machine (Philips Research, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at a source-to-image distance of 100 cm and were set to 50 kVp and 5 mAs with the patients standing. The radiographic images were retrieved using a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) (IMPAX; Agfa Healthcare, Mortsel, Belgium), and radiographic measurements were performed using PACS software.

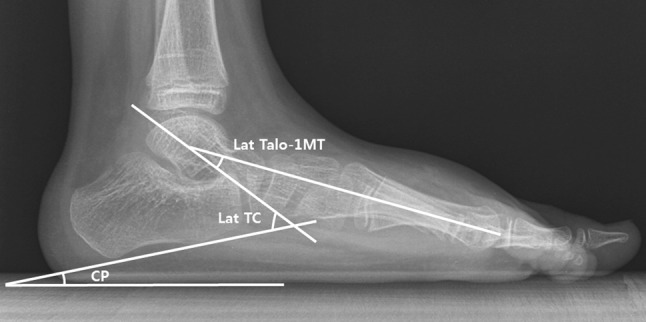

On the lateral foot weightbearing radiographs, the following six items were measured: calcaneal pitch angle, lateral talocalcaneal angle, lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, naviculocuboid overlap, calcaneal length, and calcaneocuboid subluxation. The calcaneal pitch angle was the angle between a line drawn along the edge of the plantar soft tissue shadow and a line drawn along the lower margin of the calcaneus [25]. The lateral talocalcaneal angle was the angle between a line drawn along the lower margin of the calcaneus and a line drawn through the midpoints of the talar head and neck [26]. The lateral talus-first metatarsal angle was the angle between a line bisecting the long axis of the first metatarsal bone and a line drawn through the midpoints of the talar head and neck [26] (Fig. 1). The naviculocuboid overlap was the overlapped portion of the navicular and cuboid divided by the vertical height of the cuboid [6]. Calcaneal length was the distance between the midpoint of the anterior articular surface of the calcaneus and the most posterior aspect of the calcaneus. It was divided by the width of the widest portion of the distal tibial metaphysis for normalization. The calcaneocuboid subluxation was the angle between a line drawn through the midpoint of the articular surface of the calcaneus and the most posterior aspect of the calcaneus and a line drawn through the midpoint of the articular surface of the cuboid and the most posterior aspect of the calcaneus (Fig. 2). On the AP foot weightbearing radiographs, the AP talus-first metatarsal angle was measured. The AP talus-first metatarsal angle was the angle between a line bisecting the anterior articular surface of the talus and a line bisecting the long axis of the first metatarsal bone [26] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

On the lateral foot weightbearing radiographs, the calcaneal pitch angle (CP) is the angle between a line drawn along the edge of the plantar soft tissue shadow and a line drawn along the lower margin of the calcaneus. The lateral talocalcaneal angle (Lat TC) is the angle between a line drawn along the lower margin of the calcaneus and a line drawn through the midpoints of the talar head and neck. The lateral talus-first metatarsal angle (Lat talo-1MT) is the angle between a line bisecting the long axis of the first metatarsal bone and a line drawn through the midpoints of the talar head and neck.

Fig. 2.

On the lateral foot weightbearing radiographs, the naviculocuboid overlap (A/B) is the overlapped portion of the navicular and cuboid divided by the vertical height of the cuboid. The relative calcaneal length (C/E) is the distance between midpoint of the anterior articular surface of the calcaneus and the most posterior aspect of the calcaneus divided by the width of the widest portion of the distal tibial. The calcaneocuboid subluxation was the angle between a line drawn through the midpoint of the articular surface of the calcaneus and the most posterior aspect of the calcaneus (C) and a line drawn through the midpoint of the articular surface of the cuboid and the most posterior aspect of the calcaneus (D).

Fig. 3.

On the AP foot weightbearing radiographs, the AP talus-first metatarsal angle is the angle between a line bisecting the anterior articular surface of the talus and a line bisecting the long axis of the first metatarsal bone.

Three orthopaedic surgeons (KHS, SGS, BA), with 9, 4, and 2 years of orthopaedic experience, respectively, assessed the interobserver reliability of the measurements of all radiographic indices. A prior sample size estimation by precision analysis indicated that a minimum of 36 feet radiographs should be assessed. Three examiners (KHS, SGS, BA) measured the radiographic indices, independently, without knowledge of the patients’ clinical information and the other orthopaedic surgeons’ measurements. All measurements were collected by a research assistant (HMK), who did not otherwise participate in the study.

All radiographic measurements were performed by one of the authors (KHS) with 9 years of orthopaedic experience on preoperative and latest followup radiographs. Radiographic measurements from postoperative radiographs were compared with those from preoperative radiographs. Patients were divided into the corrected group and the undercorrected group for AP talus-first metatarsal angle, lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and naviculocuboid overlap according to the mean values of normal alignment from a previous study [6]. The corrected group was defined as a group of patients whose radiographic indices improved over the mean value of normal alignment after calcaneal lengthening. The undercorrected group was defined as a group of patients whose radiographic indices did not reach the mean value of the normal alignment. We analyzed the cutoff values based on the preoperative radiographic measurements between the corrected and undercorrected groups. The cutoff values are the reference values that can judge the possibilities of sufficient correction of planovalgus deformity by the calcaneal lengthening.

Prior precision analysis was performed to identify the minimal sample size required for reliability testing. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were used for reliability testing at a target value of 0.80 and a 95% confidence interval width of 0.2 for three observers. The minimal sample size needed was 36 using Bonett’s approximation [4]. The ICCs and their 95% CIs were used to summarize the interobserver reliability of the radiographic measurements and were calculated in the setting using a two-way random effect model assuming a single measurement and absolute agreement. An ICC value of 1 indicated perfect reliability, and an ICC greater than 0.8 indicated excellent reliability.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the patients’ demographics and radiographic measurements. Comparison between preoperative and postoperative radiographic measurements was performed using a paired t-test. The receiver operating characteristic curve was used to define the cutoff values of preoperative radiographic measurements between the corrected and undercorrected groups after calcaneal lengthening. For the purpose of statistical independence, only the data from one foot in each patient were included for statistical analysis [21]. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (Version 18.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

In terms of the interobserver reliability, all of the radiographic measurements showed good to excellent reliability for clinical use (Table 2).

Table 2.

Interobserver reliability of radiographic parameters

| Radiographic parameters | ICC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| AP talus-first metatarsal angle | 0.736 | 0.595–0.844 |

| Calcaneal pitch angle | 0.918 | 0.864–0.954 |

| Lateral talocalcaneal angle | 0.722 | 0.521–0.848 |

| Lateral talus-first metatarsal angle | 0.793 | 0.641–0.887 |

| Naviculocuboid overlap | 0.915 | 0.859–0.953 |

| Relative calcaneal length | 0.817 | 0.709–0.895 |

| Calcaneocuboid subluxation | 0.794 | 0.673–0.881 |

ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; CI = confidence interval.

Correction of preoperative deformity was achieved to the normal range in 72% of patients for AP talus-first metatarsal angle, 12% for calcaneal pitch angle, 89% for talocalcaneal angle, 60% for lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and 63% for naviculocuboid overlap. AP talus-first metatarsal angle, lateral talocalcaneal angle, lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and naviculocuboid overlap were significantly decreased (p < 0.001) after calcaneal lengthening. Calcaneal pitch angle and relative calcaneal length were significantly increased after the operation (p < 0.001 and p = 0.016, respectively). However, calcaneocuboid subluxation significantly increased (p < 0.001) from 0.2° ± 1.5° preoperatively to 1.4° ± 1.9°, postoperatively. AP talus-first metatarsal angle, lateral talocalcaneal angle, lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and naviculocuboid overlap were improved at an average of 19.9° (95% CI, 16.6°–23.2°), 9.1° (95% CI, 7.1°–11.1°), 18.5° (95% CI, 15.4°–21.7°), and 31.2% (95% CI, 25.9%–36.4%), respectively, after calcaneal lengthening. Furthermore, these indices showed improvement beyond the values of normal alignment. Calcaneal pitch angle improved and showed the mean value of 4.4° (95% CI, 2.7°–6.0°) but did not reach the value of normal alignment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Change in radiographic measurements after calcaneal lengthening in patients with cerebral palsy

| Parameters | Preoperative | Postoperative | Mean difference | p value | Normal alignment [6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP talus-first metatarsal angle (°) | 22.3 ± 11.3 | 2.4 ± 13.6 | 19.9 ± 14.4 | < 0.001 | 10 ± 7.0 |

| Calcaneal pitch angle (°) | 2.9 ± 8.8 | 7.3 ± 8.1 | −4.4 ± 7.2 | < 0.001 | 17 ± 6.0 |

| Lateral talocalcaneal angle (°) | 47.0 ± 9.5 | 37.9 ± 9.2 | 9.1 ± 8.5 | < 0.001 | 49 ± 6.9 |

| Lateral talus-first metatarsal angle (°) | 30.2 ± 15.6 | 11.6 ± 13.1 | 18.5 ± 13.8 | < 0.001 | 13 ± 7.5 |

| Naviculocuboid overlap (%) | 69.0 ± 17.2 | 37.8 ± 22.1 | 31.2 ± 22.9 | < 0.001 | 47 ± 13.8 |

| Relative calcaneal length | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | −0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.016 | – |

| Calcaneocuboid joint subluxation (°) | 0.2 ± 1.5 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | −1.2 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 | – |

The paired t-test was used to evaluate the statistical significance between the preoperative and postoperative measurements.

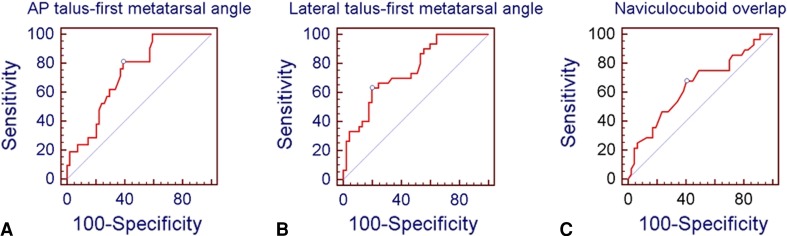

The cutoff values of preoperative measurements between the corrected and undercorrected groups were 23° AP talus-first metatarsal angle, 36° lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and 72% naviculocuboid overlap (Table 4). The receiver operating characteristic curve showed that these radiographic indices were useful to determine the cutoff values (Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Cutoff values of the preoperative radiographic measurements

| Parameters | Number of subjects (corrected group) | Number of subjects (undercorrected group) | Area under the ROC curve | 95% CI | p value | Cutoff value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP talus-first metatarsal angle (°) | 54 | 21 | 0.729 | 0.614–0.825 | 0.0001 | > 23° |

| Lateral talus-first metatarsal angle (°) | 45 | 30 | 0.754 | 0.641–0.847 | < 0.0001 | > 36° |

| naviculocuboid overlap (%) | 47 | 28 | 0.645 | 0.526–0.752 | 0.0319 | > 72% |

Corrected group = patients whose radiographic indices improved over the mean value of normal alignment; undercorrected group = patients whose radiographic indices did not reach the mean value of normal alignment; ROC curve = receiver operating characteristic curve; the ROC curve was used to define the cutoff values of the preoperative radiographic measurements between the corrected and the undercorrected groups after calcaneal lengthening.

Fig. 4A–C.

The receiver operating characteristic curves of the preoperative radiographic measurements between the corrected and undercorrected groups are shown. These curves define the cutoff values of the preoperative (A) AP talus-first metatarsal angle as 23°, (B) lateral talus-first metatarsal angle as 36°, and (C) naviculocuboid overlap as 72%.

Discussion

This study was performed to investigate the amount of correction that can be achieved after calcaneal lengthening for treatment of a planovalgus deformity in patients with CP and to provide cutoff values based on the preoperative radiographic measurements that suggest additional procedures to achieve satisfactory correction. This study showed that calcaneal lengthening osteotomy with concomitant peroneus brevis lengthening was an effective treatment modality for the planovalgus foot deformity in patients with CP. In addition, it provided guidelines for the necessity of additional procedures in terms of radiographic indices.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the outcomes of calcaneal lengthening were evaluated only by the radiographic parameters, although improvements in clinical outcomes such as foot pressure distribution also are important after the surgery. However, we performed this study with the tenet that the radiographic outcomes had a major correlation with the clinical outcomes, which were in accordance with previous studies [7, 19]. Furthermore, it is difficult to assess the clinical outcomes of calcaneal lengthening because this procedure was performed as one of the single-event multilevel surgeries to improve gait pattern. Second, the followup period was not long enough to infer that the results will be stable. Therefore, long-term followup of this patient group is required. Third, we divided the patients into the corrected group and the undercorrected group according to the values of normal alignment from a previous study [6]. This might affect the cutoff values of the preoperative radiographic measurements between the two groups. Fourth, the perfect radiologic normalization may not be the goal in nonambulatory patients. Therefore, our results cannot be generalized to all patients with CP because all patients included in this study were ambulatory. Fifth, the amount of correction might be affected by a surgical technique such as the use of autograft or stable fixation. Therefore, further study on comparison with the control group using a different surgical technique is needed. Sixth, tibiocalcaneal angle on the calcaneal axial view was not measured, although this is an important parameter in evaluating hindfoot alignment. However, it has been reported that the radiographic parameters on the standing foot AP and lateral radiographs were clinically relevant in terms of reliability, discriminant validity, and convergent validity [14]. Seventh, newly developed radiographic indices, that is, relative calcaneal length and calcaneocuboid subluxation, were used without previous validation. However, we believe these indices were somewhat validated for clinical use in this study in terms of content validity, reliability, and responsiveness, although further validation of these indices is required.

Planovalgus deformity is a complex three-dimensional malalignment characterized by hindfoot valgus, midfoot planus, midfoot pronation, relatively short lateral column, forefoot abduction, and forefoot supination [6, 14, 20]. Our results showed calcaneal lengthening corrected abduction of the forefoot and subluxation of the talonavicular joint as represented by postoperative reduction of the AP talus-first metatarsal angle. A decreased lateral talocalcaneal angle implied correction of the hindfoot valgus deformity and reduction of the lateral talus-first metatarsal angle suggested correction of midfoot planus and talonavicular joint subluxation. Postoperative correction of midfoot pronation deformity can be interpreted as a reduction of the naviculocuboid overlap. The increase of calcaneal pitch angle suggested restoration of the medial longitudinal arch. Numerous studies reported that calcaneal lengthening was a successful treatment option for planovalgus foot deformity in patients with CP (Table 5) [1, 2, 5, 9, 18–20, 28, 29]. Amounts of deformity correction in previous studies were 3.6° to 21.7° AP talus-first metatarsal angle, 2.5° to 11.4° calcaneal pitch angle, −5° to 9.5° lateral talocalcaneal angle, and −9° to 24.2° lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and those in our study were within the ranges of previous studies. In our study, calcaneocuboid joint subluxation substantially increased after calcaneal lengthening, as was mentioned in previous studies [1, 15, 16, 29]. If calcaneocuboid joint subluxation could lead to important consequences to avoid diseases such as degenerative arthrosis, surgeons should consider the surgical method to avoid it. Further study regarding the long-term effect of calcaneocuboid joint subluxation after calcaneal lengthening is needed.

Table 5.

Previous studies on radiographic measurements after calcaneal lengthening in patients with cerebral palsy

| Study | Etiology (number of subjects) | Radiographic parameter | Preoperative (°) | Postoperative(°) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andreacchio et al. [2] | Cerebral palsy (11) | AP TN coverage | 13 ± 19 | 9 ± 10 | Not reported |

| Lat TC | 19 ± 8 | 24 ± 8 | |||

| Lat talo-1MT | 0 ± 7 | 9 ± 11 | |||

| Oeffinger et al. [19] | Cerebral palsy (7); idiopathic (1) |

CP | 12 | 20 | Not reported |

| AP talo-1MT | 25 | 10 | |||

| Lat talo-1MT | 15 | 8 | |||

| Lat TH | 25 | 19 | |||

| Danko et al. [5] | Cerebral palsy (62); other neuromuscular (11); primary foot deformity (23) |

AP talo-1MT | 18.0 | 7.0 | < 0.0001 |

| AP TN coverage | 34.0 | 16.0 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Lat talo-1MT | 29.3 | 20.7 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Lat TC | 47.3 | 49.7 | 0.0001 | ||

| Lat TH | 41.4 | 34.7 | < 0.0001 | ||

| CP | 6.1 | 15.1 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Yoo et al. [28] | Cerebral palsy (56) | AP TC | 27.9 ± 7.6 | 16.9 ± 5.2 | 0.00016 |

| AP talo-1MT | 23.4 ± 9.2 | 1.7 ± 10.1 | 0.00012 | ||

| Lat TC | 37.6 ± 7.0 | 28.1 ± 5.2 | 0.00021 | ||

| Lat talo-1MT | 24.9 ± 9.2 | 4.8 ± 7.7 | 0.00043 | ||

| CP | 4.1 ± 5.1 | 11.6 ± 6.1 | 0.00047 | ||

| Noritake et al. [18] | Cerebral palsy (16) | AP talo-1MT | 21.4 ± 10.3 | 1.2 ± 9.1 | < 0.0001 |

| AP TN coverage | 28.0 ± 11.7 | 8.8 ± 10.7 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Lat talo-1MT | 33.6 ± 13.2 | 15.1 ± 13.0 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Lat TH | 47.6 ± 10.9 | 28.4 ± 8.9 | < 0.0001 | ||

| CP | 3.6 ± 7.8 | 12.4 ± 8.3 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Zeifang et al. [29] | Cerebral palsy (32) | Lat TC | 42.6 ± 6.3 | 36.2 ± 6.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Lat talo-1MT | 32.9 ± 13.9 | 18.0 ± 12.5 | < 0.0001 | ||

| CP | 3.3 ± 9.9 | 13.9 ± 7.8 | < 0.0001 | ||

| AP talo-1MT | 25.3 ± 8.8 | 10.1 ± 7.1 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Park et al. [20] | Cerebral palsy (22) | AP talo-1MT | 27.7 ± 10.1 | 10.3 ± 7.9 | < 0.0001 |

| AP TC | 30.6 ± 6.5 | 27.6 ± 5.3 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Lat talo-1MT | 29.4 ± 12.7 | 5.2 ± 4.5 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Lat TC | 38.9 ± 9.5 | 42.2 ± 11.0 | > 0.05 | ||

| CP | 3.9 ± 9.8 | 11.1 ± 7.0 | 0.0053 | ||

| Adams et al. [1] | Cerebral palsy (42) | AP talo-1MT | 19.7 ± 8.3 | 1.0 ± 10.3 | < 0.05 |

| AP TN coverage | 38.1 ± 13.4 | 12.0 ± 11.8 | < 0.05 | ||

| Lat talo-1MT | 29.0 ± 10.5 | 10.0 ± 11.5 | < 0.05 | ||

| CP | 2.8 ± 8.7 | 14.2 ± 8.9 | < 0.05 | ||

| Lat TC | 44.3 ± 9.6 | 41.5 ± 11.8 | < 0.05 | ||

| Ettl et al. [9] | Cerebral palsy (19) | AP talo-1MT (ambulator) | 12.6 ± 9.4 | 9.0 ± 4.6 | < 0.05 |

| AP talo-1MT (nonambulator) | 23.9 ± 8.2 | 18.6 ± 14.0 | < 0.05 | ||

| Lat TH (ambulator) | 27.4 ± 8 | 24.0 ± 8.5 | < 0.05 | ||

| Lat TH (nonambulator) | 36.7 ± 10.5 | 29.0 ± 10.9 | < 0.05 | ||

| CP (ambulator) | 14.4 ± 7.7 | 18.4 ± 9.4 | < 0.05 | ||

| CP (nonambulator) | 12.4 ± 6.7 | 14.9 ± 4.0 | < 0.05 |

CP = calcaneal pitch angle; Lat TC = lateral talocalcaneal angle; Lat talo-1MT = lateral talus-first metatarsal angle; AP TN coverage = AP talonavicular coverage angle; AP talo-1MT = AP talus-first metatarsal angle; AP TC = AP talocalcaneal angle; Lat TH = lateral talo-horizontal angle.

It is known that increased tension in the plantar ligaments and plantar fascia contribute to create the bowstring effect, which restores the medial longitudinal arch [8, 16, 24]. Despite the relatively high reliability of the calcaneal pitch angle measurement, however, it has been shown to be a less valid method for discriminating hindfoot valgus and varus deformities and for correlating with foot pressure distribution [14]. In our study, calcaneal pitch angle improved to a mean value of 7.3°, but it did not reach the value of normal alignment. In addition, only nine of 75 patients (12%) improved for this index according to the value of normal alignment. The lateral talocalcaneal angle, which reflects hindfoot valgus, also showed low convergent and discriminant validity in a previous study [14]. In this study, lateral talocalcaneal angle not only improved beyond the value of normal alignment in most cases (67 of 75 patients [89%]), but also preoperative mean values were less than the value of normal alignment. Therefore, we believe clinical use of the calcaneal pitch angle and lateral talocalcaneal angle for assessing planovalgus deformity might be limited and we did not analyze the cutoff values of preoperative measurements for these indices. In terms of convergent validity, it has been reported that naviculocuboid overlap, AP talus-first metatarsal angle, and lateral talus-first metatarsal angle had a major correlation with that of foot pressure distribution [14]. This may suggest that forefoot abduction, midfoot pronation, and midfoot planus are important in planovalgus deformity and that these relationships may be critical in assessing the severity of such deformity preoperatively and achieving appropriate correction of deformity. Therefore, we believe providing the cutoff values of preoperative measurements for these indices has clinical implications. It has been reported that plication of the tibialis posterior tendon should be done if the correction of forefoot abduction is insufficient and the medial corrective metatarsal or medial cuneiform osteotomy should be performed if forefoot supination is still excessive after calcaneal lengthening [2, 16, 29]. We believe most surgeons determine the necessity of an additional procedure with intraoperative degrees of correction after calcaneal lengthening. However, it is difficult to evaluate whether the deformity is corrected enough or undercorrected during the operation because it is impossible to put a patient’s foot in a weightbearing position. Furthermore, it might result in the likelihood of undercorrection of deformities. Considering the cutoff values of preoperative radiographic measurements, we therefore think it is helpful for preoperative planning regardless whether additional procedures are needed.

Calcaneal lengthening with concomitant peroneus brevis lengthening is an effective procedure for correcting planovalgus foot deformity in patients with CP. For patients with greater than a 23° AP talus-first metatarsal angle, 36° lateral talus-first metatarsal angle, and 72% naviculocuboid overlap, additional procedures should be considered as a result of the possibilities of insufficient correction with calcaneal lengthening alone.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bekhzad Akhmedov MD, and Sang Gyo Seo MD, for radiographic measurements and Mi Sun Ryu BS, and Hyun Mi Kim BS, for data collection.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was waived due to retrospective design.

References

- 1.Adams SB, Jr, Simpson AW, Pugh LI, Stasikelis PJ. Calcaneocuboid joint subluxation after calcaneal lengthening for planovalgus foot deformity in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:170–174. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181982c33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreacchio A, Orellana CA, Miller F, Bowen TR. Lateral column lengthening as treatment for planovalgus foot deformity in ambulatory children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson J, Nunley J, Frankovitch K. Lateral talocalcaneal angle in assessment of subtalar valgus: follow-up of seventy Grice-Green arthrodeses. Foot Ankle. 1983;4:56–63. doi: 10.1177/107110078300400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonett DG. Sample size requirements for estimating intraclass correlations with desired precision. Stat Med. 2002;21:1331–1335. doi: 10.1002/sim.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danko AM, Allen B, Jr, Pugh L, Stasikelis P. Early graft failure in lateral column lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:716–720. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200411000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davids JR, Gibson TW, Pugh LI. Quantitative segmental analysis of weight-bearing radiographs of the foot and ankle for children: normal alignment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:769–776. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000173244.74065.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davitt JS, MacWilliams BA, Armstrong PF. Plantar pressure and radiographic changes after distal calcaneal lengthening in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:70–75. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200101000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinucci KR, Christensen JC, Dinucci KA. Biomechanical consequences of lateral column lengthening of the calcaneus: Part I. Long plantar ligament strain. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2004;43:10–15. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettl V, Wollmerstedt N, Kirschner S, Morrison R, Pasold E, Raab P. Calcaneal lengthening for planovalgus deformity in children with cerebral palsy. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30:398–404. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans D. Calcaneo-valgus deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:270–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grice DS. An extra-articular arthrodesis of the subastragalar joint for correction of paralytic flat feet in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1952;34:927–940; passim. [PubMed]

- 12.Horton GA, Olney BW. Triple arthrodesis with lateral column lengthening for treatment of severe planovalgus deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:395–400. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keim HA, Ritchie GW. Weight-bearing roentgenograms in the evaluation of foot deformities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;70:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KM, Chung CY, Park MS, Lee SH, Cho JH, Choi IH. Reliability and validity of radiographic measurements in hindfoot varus and valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2319–2327. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Momberger N, Morgan JM, Bachus KN, West JR. Calcaneocuboid joint pressure after lateral column lengthening in a cadaveric planovalgus deformity model. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:730–735. doi: 10.1177/107110070002100903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosca VS. Calcaneal lengthening for valgus deformity of the hindfoot: results in children who had severe, symptomatic flatfoot and skewfoot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:500–512. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosca VS. Letter to the JPO editors re: article by Andreacchio et al entitled ‘lateral column lengthening as treatment for planovalgus foot deformity in ambulatory children with spastic cerebral palsy’ (J Pediatr Orthop 2000;20:501–505) J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:412. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000217720.18352.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noritake K, Yoshihashi Y, Miyata T. Calcaneal lengthening for planovalgus foot deformity in children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:274–279. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oeffinger DJ, Pectol RW, Jr, Tylkowski CM. Foot pressure and radiographic outcome measures of lateral column lengthening for pes planovalgus deformity. Gait Posture. 2000;12:189–195. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(00)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park KB, Park HW, Lee KS, Joo SY, Kim HW. Changes in dynamic foot pressure after surgical treatment of valgus deformity of the hindfoot in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1712–1721. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park MS, Kim SJ, Chung CY, Choi IH, Lee SH, Lee KM. Statistical consideration for bilateral cases in orthopaedic research. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1732–1737. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips GE. A review of elongation of os calcis for flat feet. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65:15–18. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B1.6337167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rathjen KE, Mubarak SJ. Calcaneal-cuboid-cuneiform osteotomy for the correction of valgus foot deformities in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:775–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangeorzan BJ, Mosca V, Hansen ST., Jr Effect of calcaneal lengthening on relationships among the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:136–141. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steel MW, 3rd, Johnson KA, DeWitz MA, Ilstrup DM. Radiographic measurements of the normal adult foot. Foot Ankle. 1980;1:151–158. doi: 10.1177/107110078000100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanderwilde R, Staheli LT, Chew DE, Malagon V. Measurements on radiographs of the foot in normal infants and children. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:407–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westberry DE, Davids JR, Roush TF, Pugh LI. Qualitative versus quantitative radiographic analysis of foot deformities in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:359–365. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181653b51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo WJ, Chung CY, Choi IH, Cho TJ, Kim DH. Calcaneal lengthening for the planovalgus foot deformity in children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:781–785. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000184650.26852.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeifang F, Breusch SJ, Doderlein L. Evans calcaneal lengthening procedure for spastic flexible flatfoot in 32 patients (46 feet) with a followup of 3 to 9 years. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:500–507. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]