The interaction of ATAXIN-1 (ATXN1) with the transcriptional repressor Capicua (CIC) plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1), a polyglutamine expansion neurodegenerative disease. This study presents the crystal structure of the AXH domain of ATXN1 bound to CIC and then provides evidence showing that CIC binding to ATXN1 disrupts homodimerization of ATXN1 and induces a new form of dimerization mediated by CIC. These results indicate the interdependent nature of ATXN1–CIC complex formation and provide a possible target for modulating SCA1 pathogenesis.

Keywords: complex, neurodegenerative disease, SCA1

Abstract

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) is a dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disease caused by polyglutamine expansion in Ataxin-1 (ATXN1). ATXN1 binds to the transcriptional repressor Capicua (CIC), and the interaction plays a critical role in SCA1 pathogenesis whereby reducing CIC levels rescues SCA1-like phenotypes in a mouse model. The ATXN1/HBP1 (AXH) domain of ATXN1 mediates its homodimerization as well as the interaction with CIC. Here, we present the crystal structure of ATXN1's AXH domain bound to CIC and show that the binding pocket of the AXH domain to CIC overlaps with the homodimerization pocket of the AXH domain. Thus, the binding to CIC disrupts the homodimerization of ATXN1. Furthermore, the binding of CIC reconfigures the complex to allow another form of dimerization mediated by CIC, showing the intricacy of protein complex formation and reconfiguration by ATXN1 and CIC. Identifying the surfaces mediating the interactions between CIC and ATXN1 reveals a critical role for CIC in the reconfiguration of the AXH dimers and might provide insight into ways to target the ATXN1/CIC interactions to modulate SCA1 pathogenesis.

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) is one of nine polyglutamine (polyQ) expansion neurodegenerative diseases. SCA1 is caused by the polyQ expansion in Ataxin-1 (ATXN1) (Orr et al. 1993). It is believed that the polyQ expansion in ATXN1 modulates its normal activity to cause the pathology (Lim et al. 2008) ATXN1 has many binding partners, including Capicua (CIC), a transcriptional repressor that is involved in SCA1 pathogenesis. In fact, reducing CIC levels by 50% rescues many SCA1-like phenotypes in a mouse model of the disease (Fryer et al. 2011). A highly conserved ATXN1/HBP1 (AXH) domain in ATXN1, which is required for SCA1 pathogenesis (Tsuda et al. 2005), interacts with an N-terminal region of CIC (Lam et al. 2006). Furthermore, the AXH domain is required for ATXN1 self-association, which is also shown by the crystal structure of the AXH domain alone (Burright et al. 1997; Chen et al. 2004). Although ATXN1 interacts with several cellular partners and regulates their activities, the biochemical properties of ATXN1 and the molecular mechanism mediating complex formation of ATXN1 with a protein such as CIC are still not well understood. Here, we present the crystal structures of ATXN1's AXH domain bound with CIC peptides. These structures, followed by biochemical and in vivo analysis, reveal that the binding of CIC to ATXN1 dissociates the ATXN1 homodimer and induces a new form of ATXN1 dimer mediated by CICs. These data implicate that ATXN1 undergoes reconfiguration of complex formation upon CIC binding.

Result and Discussion

Crystal structure of the ATXN1–CIC complex

To understand the molecular mechanism mediating ATXN1–CIC interaction, we determined the crystal structure of ATXN1's AXH domain bound to a highly conserved N-terminal region of CIC (28–48 amino acids, CIC21: EPRSVAVFPWHSLVPFLAPSQ) at 2.5 Å resolution using the single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) method (Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Fig. S1). The structure of the AXH domain bound with CIC peptide is almost identical with the structure of the AXH domain alone (Chen et al. 2004). The complex structure reveals that CIC21 binds to a highly hydrophobic pocket of the AXH domain (Fig. 1). Highly conserved residues (W37, L40, and V41) of CIC21 form hydrophobic interactions with highly conserved residues (V591, S602, and L686) of the AXH domain (Fig. 1). To confirm that the interaction observed in the crystal structure is biologically relevant, we first mutagenized the conserved residues of CIC21 and examined the binding by maltose-binding protein (MBP) pull-down assay (Fig. 2A, top). Among the conserved residues, mutating the conserved W37 to A (W37A), and L40 to S (L40S) of CIC21 severely impaired the binding abilities of CIC21 to the AXH domain, while mutating other conserved residues moderately affected the binding abilities. We next generated several mutations in the hydrophobic pocket of the AXH domain. Among these mutants, combined mutations in the pocket (V591A_S602D, V591A_L686E, or S602D_L686E) abolish the interaction between the AXH domain and CIC21 (Fig. 2A, bottom).

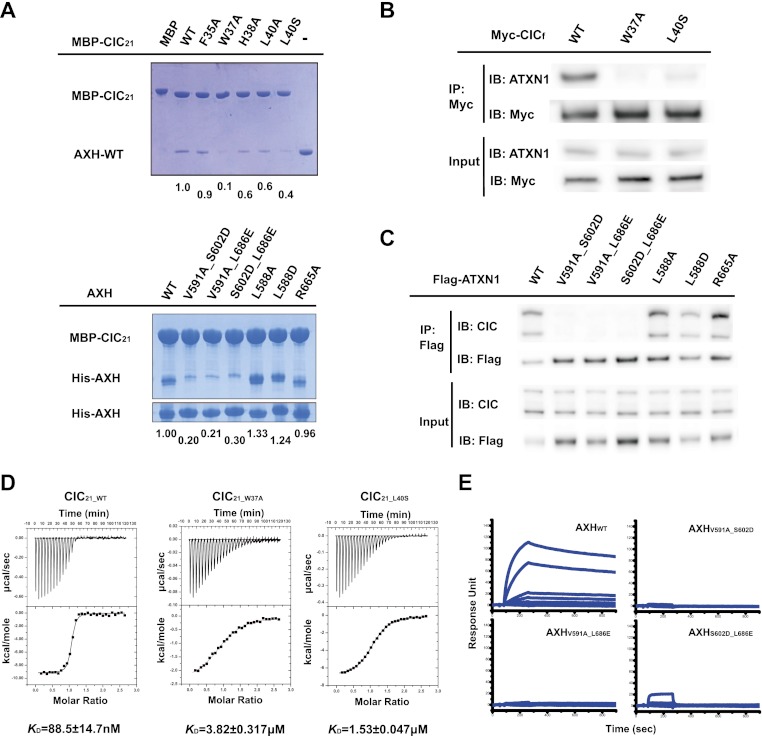

Figure 1.

Crystal structure shows that CIC21 binds to a highly hydrophobic pocket of the AXH domain. (A) Ribbon representation of the AXH domain (blue) and the bound CIC21 peptide shown in ball-and-stick (yellow). (B) Detailed interaction between the AXH domain and CIC21 peptide showing that CIC21 binds to the hydrophobic pocket in the AXH domain. (C) Electrostatic surface representation of the AXH domain bound with CIC21 (yellow) showing hydrophobic character of the pocket.

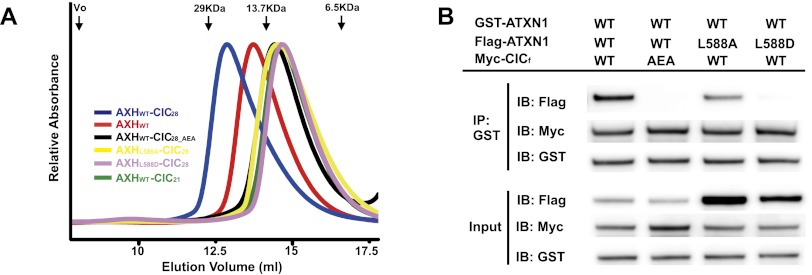

Figure 2.

Mutation in critical residues disrupts the interaction between the ATXN1 and CIC both in vitro and in vivo. (A, top) MBP pull-down assay with wild-type and mutant MBP-CIC21 and the wild-type AXH domain. (Bottom) MBP pull-down assay with wild-type MBP-CIC21 and wild-type and mutant AXH domains. Mutations in MBP-CIC21 (W37A and L40S) and His-AXH (V591A_S602D, V591A_L686E, or S602D_L686E) greatly disrupt the interaction. The same amounts of the AXH domains used for MBP pull-down were shown by His pull-down for His-AXH domains. The amount of bound AXH domain is quantified at the bottom of the gels. (B) In vivo binding between endogenous ATXN1 and Myc-tagged full-length CIC (CICf). One-hundred nanograms of each CICf construct was used for transfection. (C) In vivo binding between endogenous CIC and full-length wild-type and mutant ATXN1 (R566A is a negative control). The upper band of CIC is the longer isoform (CIC-L), and the lower band is the short isoform (CIC-S). Fifty nanograms of each Flag-ATXN1 construct was used for transfection. (D) ITC measurements between the AXH domain and CIC21_WT, CIC21_W37A, and AXH-CIC21_L40S. CIC21_W37A and AXH-CIC21_L40S have greatly reduced affinity to the AXH domain compared with CIC21_WT. (E) SPR measurements of the binding affinities between CIC21 and the AXH domain. The KD for the binding between CIC21 and AXHWT is ∼40 nM.. AXHV591A_S602D, AXHV591A_L686E, and AXHS602D_L686E fail to bind to CIC21.

To determine whether the interaction between the AXH domain and CIC observed in the crystal structure and whether in vitro pull-down assays reflect in vivo interactions in the context of the full-length proteins, we transfected either Myc-tagged full-length CIC (CICf_WT) or full-length CIC mutants (CICf_W37A and CICf_L40S) and asked whether the mutations disrupt the interaction between endogenous ATXN1 and CIC in vivo. Consistent with the structural and in vitro binding data, the conserved hydrophobic residues (W37 and L40) of CIC are critical for ATXN1 binding in vivo (Fig. 2B). Next, we transfected either Flag-tagged full-length wild-type or mutant ATXN1 and examined the binding abilities with endogenous CIC. We found that the AXH mutants (ATXN1V591A_S602D, ATXN1V591A_L686E, and ATXN1S602D_L686E) fail to interact with endogenous CIC, but a negative control mutant (R665A) shows binding comparable with that of wild-type ATXN1 (Fig. 2C). These data validate the information deduced from the crystal structure.

Disruption of ATXN1 homodimerization upon CIC binding

The previous structure of the AXH domain shows that the AXH domain forms a homodimer (Chen et al. 2004). Interestingly, the same pocket on ATXN1 that mediates CIC binding was initially identified to be involved in homodimerization of the AXH domain, suggesting that CIC binding might disrupt AXH domain homodimerization (Supplemental Fig. 2A,B; Chen et al. 2004). Therefore, we investigated whether the CIC binding to the AXH domain disrupts AXH homodimerization by size exclusion chromatography (Supplemental Fig. 3). While the AXH domain alone elutes at fractions corresponding to the AXH dimer, the AXH domain bound to CIC21 (AXH_CIC21) elutes in a fraction similar to the N-terminal-deleted AXH domain (AXH_ΔN), which is supposed to be a monomer, since the N terminus of the AXH domain is critical for its homodimerization. Combined with the structure of AXH–CIC complex, these data show that the binding of CIC to the hydrophobic pocket of the AXH domain disrupts the homodimerization of ATXN1.

ATXN1–CIC interactions

To measure the binding affinity between the AXH domain and CIC in a quantitative manner, we assayed binding affinities using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Wild-type CIC21 binds to the AXH domain with ∼100 nM KD affinity, while CIC21 mutants (CIC21_W37A and CIC21_L40S) show decreased affinity, with a KD in the micromolar range (Fig. 2D). We next measured the binding between wild-type CIC21 and the AXH mutants (Supplemental Fig. 4). Unexpectedly, the binding between CIC21 and the AXHV591A_S602D mutant shows endothermic kinetics. Moreover, the double mutants (AXHV591A_L686E and AXHS602D_L686E), which fail to interact with CIC21 by MBP pull-down assay, show apparent binding affinities comparable with AXHWT to CIC21. We also measured the binding between wild-type CIC21 and AXH single mutants (AXHV591A, AXHS602D, and AXHL686E) as well as a triple mutant (AXHV591A_S602D_L686E) (Supplemental Fig. 5). All single mutants show binding affinities comparable with the wild-type, and the triple mutant shows almost no binding. Furthermore, to investigate the dimerization status of the double mutants, we performed size exclusion chromatography and found that all double mutants elute as monomer forms, indicating that the dimerization interface was disrupted (Supplemental Fig. 6). The double mutants affect not only the homodimerization of the AXH domain, but also the hydrophobic interface between the AXH domain and CIC (Fig. 2A). This makes it difficult to interpret the binding between the AXH domain and CIC21 by ITC.

Therefore, we decided to directly measure the binding between the AXH mutants (AXHV591A_S602D, AXHV591A_L686E, and AXHS602D_L686E) and CIC21 using surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which measures the binding events only between the AXH domain and CIC. We immobilized biotinylated CIC21 peptide on a SA chip as a ligand and examined the bindings of the AXH domains as analytes. Consistent with the MBP pull-down assay, SPR analysis shows that the wild-type AXH domain binds to CIC21 with ∼40 nM KD affinity, while the mutant AXH variants are unable to bind to CIC (Fig. 2A [bottom panel], E). These data are consistent with the notion that CIC binds the hydrophobic pocket of the AXH domain and disrupts the homodimerization of the AXH domain.

Reconfiguration of complex formation by ATXN1 and CIC

Upon further examination of the structure, we noticed that there are three molecules of the AXH–CIC21 complexes in an asymmetric unit in the crystal. Among them, the structure of two AXH–CIC21 complexes suggests a possible new form of ATXN1 dimerization mediated by the CIC dimer (Supplemental Fig. 7). To assess the biological relevance of this new form of AXH–CIC complex, we determined the crystal structure of the AXH domain bound to a longer CIC peptide (21–48 amino acids, CIC28:MFVWTNVEPRSVAVFPWHSLVPFLAPSQ) at 3.15 Å resolution by molecular replacement method using the AXH domain alone without CIC21 as a search model (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 1). There are two AXH–CIC28 molecules in an asymmetric unit of the crystals, which belong to a different space group with the AXH–CIC21 crystals (Supplemental Table 1), indicating that the AXH–CIC28 molecules have a different packing environment with the AXH–CIC21. Indeed, the AXH domains make a new form of dimerization mediated by the CIC28 dimer (Fig. 3A). Two CIC28 molecules positioned in an anti-parallel manner make an intertwining interaction between each other, and these two intertwined CIC28 molecules bridge two AXH domains. Specifically, hydrophobic residues (MFVW, 21–24 amino acids) of CIC28 interact with a hydrophobic patch composed of F632, V634, V645, and Y649 from the AXH domain as well as with F43 from the other CIC28 (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, four molecules (two CIC28 molecules and two AXH domains) interact together, forming a hydrophobic core composed of I580 and L588 from both AXH domains and V32 and V34 from both CIC28 molecules (Fig. 3C). To examine whether the AXH domain dimerization mediated by CIC occurs in a more physiological condition, we analyzed complex formation of AXH and CIC comparing the sizes of several AXH–CIC complexes by size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 4A). The wild-type CIC28–AXH domain elutes earlier than the AXH domain alone (homodimer), indicating that the AXH–CIC28 complex forms a larger complex or a complex with extended conformation. Consistent with this observation, the CIC28-mediated AXH dimer structure has an extended shape compared with the AXH homodimer. We then generated a triple mutation in CIC (CIC28_AEA: F22A_V23E_W24A), which would affect the CIC-mediated AXH dimerization but not AXH–CIC interaction. We also generated AXH mutants (L588A and L588D) to disrupt the hydrophobic core where four molecules junction without affecting the CIC-binding pocket at the AXH domain (Fig. 2A,C). All of the mutants elute at similar fractions where AXH–CIC21 elutes, which is shown to be a monomer, suggesting that the mutations disrupt the CIC-mediated AXH dimerization, resulting in a AXH–CIC monomer. To analyze the complex formation more quantitatively, we measured the size of the complexes using size exclusion chromatography multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) (Supplemental Fig. 8). SEC-MALS analysis shows that the molecular weight of the AXHWT–CIC28 shows 33.8 kDa, indicating that AXHWT–CIC28 forms a heterotetramer of AXHWT–CIC28, whereas AXHL588D–CIC28 shows a heterodimer size. Interestingly, AXHWT–CIC28_AEA and AXHL588A–CIC28 show slightly higher molecular weights than their heterodimer sizes, suggesting the existence of partial heterotetramers. Collectively, SEC-MALS data with the gel filtration analysis indicate that the CIC dimer can reconfigure the ATXN1 dimer and form a heterotetramer with ATXN1s.

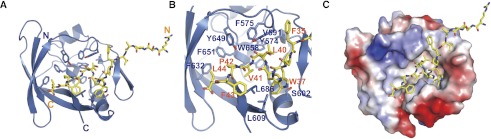

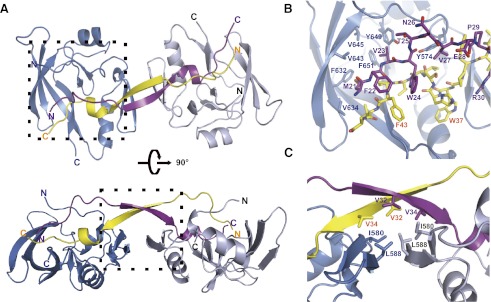

Figure 3.

Crystal structure showing CIC28-mediated heterotetramer formation with the AXH domain. (A) Ribbon representation of the AXH–CIC28 structure showing that CIC28 reconfigures the complex formation of the AXH domain (the AXH domain is shown in blue and light blue, and the CIC28 peptide is shown in yellow and purple). (B) Detailed structure between AXH–CIC28 and the other CIC28 peptide (shown in the dashed box in the top panel of A). (C) Detailed structure of the hydrophobic core where two AXH domains and two CIC28 peptides interact (shown in the dashed box in the bottom panel of A).

Figure 4.

CIC mediates the dimerization of ATXN1 to form heterotetramers both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Size exclusion chromatography analysis of AXH–CIC complexes. The AXH domain alone forms a dimer. AXH–CIC28 elutes earlier than the AXH domain alone, suggesting that AXH–CIC28 forms a larger complex. (Blue) AXH–CIC28; (red) the AXH domain alone; (black) AXH–CIC28_AEA; (yellow) AXHL588A–CIC28; (pink) AXHL588D–CIC28; (green) AXH–CIC21. The black arrows indicate size markers and void volume (Vo). (B) In vivo binding showing that CIC mediates ATXN1 dimerization. Wild-type GST-ATXN1 (100 ng), wild-type and mutant Flag-ATXN1 (80 ng), and wild-type and mutant CICf (1 μg) were transfected. GST-ATXN1 can pull down Flag-ATXN1 in the presence of wild-type CICf and wild-type Flag-ATXN1, but the interaction is abolished or reduced with mutant CICf or mutant Flag-ATXN1.

To determine whether the structural data and in vitro studies regarding the CIC28-mediated complex formation of AXH reflect the in vivo complex formation by full-length ATXN1 and CIC, we transfected GST-ATXN1 and Flag-ATXN1 with saturated amounts of wild-type Myc-CICf (CICf_WT) or Myc-CIC mutant (CICf_AEA: F22A_V23E_W24A) and examined CIC-mediated ATXN1 dimerization (Fig. 4B). Figure 4B shows that wild-type GST-ATXN1 is able to bring down Flag-ATXN1 when cotransfected with CICf_WT but not with mutant CICf_AEA, suggesting that the dimer formation between GST-ATXN1 and Flag-ATXN1 is mediated by CIC and that the AEA mutation in CIC disrupts ATXN1 dimerization. These data are consistent with the structural observation that the hydrophobic residues (F22, V23, and W24) are critical for CIC-mediated dimerization of ATXN1. Next, we transfected wild-type GST-ATXN1 and Flag-ATXN1 mutants (L588A and L588D) with CICf_WT and examined the CIC-mediated dimerization of ATXN1. The mutants (L588A and L588D) would affect the AXH dimerization mediated by CIC but not the interaction between AXH and CIC (Fig. 2C). Figure 4B shows that wild-type GST-ATXN1 failed to pull down the Flag-ATXN1 mutant (L588D) in the presence of wild-type Myc-CICf. The small amount of Flag-ATXN1 mutant (L588A) pulled down by GST-ATXN1 was likely due to the hydrophobic property of alanine substitution. Collectively, these data show that the CIC binding to ATXN1 disrupts the homodimerization and reconfigures to make a CIC-mediated ATXN1 dimer complex.

The interaction between polyQ-expanded ATXN1 and CIC plays a critical role in SCA1 pathogenesis (Fryer et al. 2011). The notion that the binding of CIC to ATXN1 substantially reconfigures the arrangement of ATXN1 prompted us to propose that the rearrangement of ATXN1 homodimer to the CIC-mediated ATXN1 complex might affect the interaction with one of the many other binding partners (Lim et al. 2008). Previous work showed that the level of CIC protein is reduced in the absence of ATXN1, and the level of ATXN1 is also reduced upon reduction of CIC in a dose-dependent manner (Fryer et al. 2011).

The crystal structure in this study reveals that the ATXN1 dimer is mediated by the CIC dimer and that the CIC dimer is mediated by the ATXN1 dimer, indicating that the formation of the ATXN1–CIC complex is highly interdependent. These observations suggest that the protein stabilities of ATXN1 and CIC might be contingent on ATXN1–CIC complex formation. Recently, it was shown that the polyQ in Huntington's disease protein modulates the activity of its endogenous binding partner, Polycomb-repressive complex2 (Seong et al. 2010). Furthermore, it was shown that in SCA1 knock-in mice, some CIC target genes are hyperrepressed, while other CIC target genes are derepressed (Fryer et al. 2011). Therefore, it is tantalizing to propose that the expanded polyQ in ATXN1–CIC–CIC–ATXN1 configuration may alter the transcriptional repressor activity of CIC, which may be involved in SCA1 pathology. However, the exact mechanism of SCA1 pathology regarding the ATXN1 and CIC interaction needs to be further investigated.

This study provides the first structural and molecular insights into the interaction between one polyQ disease protein, ATXN1, and its endogenous binding partner, CIC. Our findings underscore the importance of domains beyond the glutamine tract for interactions that modulate disease pathogenesis. Given the in vivo benefits of reducing CIC levels in the SCA1 mouse model (Fryer et al. 2011), the identification of the surface mediating the ATXN1–CIC interaction opens up the possibility of developing agents that target the ATXN1–CIC interactions to modulate SCA1 pathogenesis.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

The AXH domain (563–689 amino acids) from human ATXN1 was cloned into a pET28a vector, generating an N-terminal His tag. The AXH domain was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and purified with an Ni-affinity column. The N-terminal His tag was cleaved by TEV protease (Life Technologies) and further purified with a Hitrap Q (GE Healthcare) anion exchange chromatography and with a Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) size exclusion chromatography. The AXH mutants and the N-terminal-deleted AXH were purified as the wild-type AXH domain. For the Se-substituted AXH domain, we decided to mutate Ile580 and Ile605 to methionines to obtain better phase information using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), and the Se-Substituted AXH domain was purified in the same way as the wild-type.

Crystallization and structure determination

The AXH–CIC21 complex was crystallized in the presence of 3 mM CIC21 peptide (EPRSVAVFPWHSLVPFLAPSQ) in a reservoir solution containing 0.1 M calcium chloride, 24% (v/v) PEG 3350, and 4% (v/v) pentaerythritol ethoxylate by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method at 20°C. The AXH–CIC28 complex was crystallized in the presence of CIC28 peptide (MFVWTNVEPRSVAVFPWHSLVPFLAPSQ) in a mother liquor containing 1.6 M NaCl, 3% (v/v) glycerol, 16% (w/v) PEG 3350, and 1 mM L-glutathione. AXH–CIC21 crystals were soaked in a cryo-solution containing 26% (w/v) PEG3350 and 10% (v/v) glycerol. For AXH–CIC28, the mother liquor solution was used as a cryo-protectant. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the beamline 17A at Photon Factory and the beamline 5C at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory. The data were processed using HKL2000. The AXH–CIC21 structure was determined by Se-SAD method using Phenix and was refined using the CNS program. The AXH–CIC28 structure was solved by the molecular replacement method using the AXH apo-structure as a search model and refined using the CNS program. The structure factors and coordinates of the structures were deposited at the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org; PDB ID 4J2J for AXH–CIC21 and 4J2L for AXH–CIC28).

Pull-down assay

MBP-tagged wild-type and mutant CIC21 were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified using amylose (New England Biolabs) resin. The purified wild-type AXH domain was incubated with each MBP-tagged CIC21 bound to amylose resin. The amylose resin was washed using the lysis buffer. The interaction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. For wild-type MBP–CIC21 and the mutant AXH binding, His-tagged wild-type or mutant AXH domains and MBP-tagged CIC21 were coexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells and purified using amylose (New England Biolabs) resin or Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) resin. Using SDS-PAGE, the interaction was analyzed. The pull-downs were repeated three times with separately grown cells. The amount of proteins was quantified using ChemiDoc MP (Bio-Rad) using Image Lab software.

ITC

The interaction of AXH and CIC21 was measured using ITC using VP-ITC (MicroCal) at 25°C. The AXH domain and CIC21 peptide were prepared in a buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5). The wild-type or mutant AXH domains were added at 25 μM concentration in the sample chamber and titrated with CIC21 peptide with 500 μM concentration. Data were analyzed using the Origin program.

SPR

The interactions between the AXH domain and CIC21 were measured by SPR using Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare). Biotinylated CIC21 was immobilized as a ligand on a Sensor Chip SA with 80RU, and the immobilized surface was stabilized with a regeneration buffer containing 50 mM NaOH. The wild-type or mutant AXH domains were used as analytes (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 200, and 400 nM) using a buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 1mM EDTA as a running buffer. The association was measured for 3 min, and the dissociation was measured for 12 min. The surface of chip was regenerated with two injections of the regeneration buffer for 4 min each time. The data were analyzed using BiaEvaluation software (GE Healthcare).

Dimerization assay

The size of AXH–CIC complexes were analyzed with a Superdex 75 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) size exclusion chromatography equilibrated with a buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5).

In vivo binding assay

Mammalian expression vectors Flag-ATXN1 (Flag-Atxn1[2Q]), CICf_WT (Myc-CicS), and GST-ATXN1 (GST-Atxn1[2Q]) have been described previously (Chen et al. 2003; Lim et al. 2008). CICf_WT (Myc-CICf) was generated by PCR cloning of mouse Cic cDNA (DNASU, MmCD00083297) into pCMV-Myc vector (Clontech). The CICf_AEA construct was modified from CICf_WT by PCR cloning using primers with a mutagenized sequence. The other constructs were made by site-directed mutagenesis with QuickChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) using either Flag-ATXN1 or CICf_WT as a template. HEK293Ta cells were cultured in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and were plated in six-well plates 1 d before transfection. On the day of transfection, corresponding DNA constructs were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Two days later, cells were lysed for 20 min at 4°C in lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween-20, complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). After centrifugation, 500 μg of soluble proteins was used for immunoprecipitation with glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE), Anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma), or mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc antibody (Sigma, clone 9E10) and protein G Sepharose 4 Fast Flow beads (GE). The pellets were resuspended in 2× sample buffer after being washed three times in washing buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). The protein samples were loaded on NuPage 4%–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and transferred to Trans-Blot nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Guinea pig polyclonal anti-CIC (126) (Lam et al. 2006), rabbit polyclonal anti-ATXN1 (11750) (Servadio et al. 1995), mouse monoclonal anti-Flag M2 (Sigma), rabbit polyclonal anti-GST (Sigma), and mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc (Sigma, clone 9E10) were used as primary antibodies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Song laboratory for discussion. We also thank J. Park, D. Kim, H.-C. Shin, and B. Ku for technical assistant; S.-B. Hong and H.K. Song for MALS analysis; and H.-Y. Kim at Korea Basic Science Institute for initial crystal screening. The X-ray data were collected at Photon Factory and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory. This work was partially supported by the World Class University (WCU) program grant R31-2008-000-10071-0, and grants 2011-0031416, 2011-0020334, and 2011-0031955 to J.S. E.K. and J.S. conceived of the study. E.K, H.-C.L., H.Y.Z, and J.S. designed the experiments. E.K. and J.S. performed structural studies and in vitro binding experiments. H.-C.L. performed in vivo binding experiments. E.K., H.-C.L., H.Y.Z., and J.S. analyzed the data, and E.K. and J.S. wrote the paper. H.Y.Z. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and portions of the work were supported by NIH grant NS27699 to H.Y.Z.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.212068.112.

References

- Burright EN, Davidson JD, Duvick LA, Koshy B, Zoghbi HY, Orr HT 1997. Identification of a self-association region within the SCA1 gene product, ataxin-1. Hum Mol Genet 6: 513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HK, Fernandez-Funez P, Acevedo SF, Lam YC, Kaytor MD, Fernandez MH, Aitken A, Skoulakis EM, Orr HT, Botas J, et al. 2003. Interaction of Akt-phosphorylated ataxin-1 with 14-3-3 mediates neurodegeneration in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Cell 113: 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Allen MD, Veprintsev DB, Lowe J, Bycroft M 2004. The structure of the AXH domain of spinocerebellar ataxin-1. J Biol Chem 279: 3758–3765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer JD, Yu P, Kang H, Mandel-Brehm C, Carter AN, Crespo-Barreto J, Gao Y, Flora A, Shaw C, Orr HT, et al. 2011. Exercise and genetic rescue of SCA1 via the transcriptional repressor Capicua. Science 334: 690–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YC, Bowman AB, Jafar-Nejad P, Lim J, Richman R, Fryer JD, Hyun ED, Duvick LA, Orr HT, Botas J, et al. 2006. ATAXIN-1 interacts with the repressor Capicua in its native complex to cause SCA1 neuropathology. Cell 127: 1335–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Crespo-Barreto J, Jafar-Nejad P, Bowman AB, Richman R, Hill DE, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY 2008. Opposing effects of polyglutamine expansion on native protein complexes contribute to SCA1. Nature 452: 713–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HT, Chung MY, Banfi S, Kwiatkowski TJ Jr, Servadio A, Beaudet AL, McCall AE, Duvick LA, Ranum LP, Zoghbi HY 1993. Expansion of an unstable trinucleotide CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Genet 4: 221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong IS, Woda JM, Song JJ, Lloret A, Abeyrathne PD, Woo CJ, Gregory G, Lee JM, Wheeler VC, Walz T, et al. 2010. Huntingtin facilitates polycomb repressive complex 2. Hum Mol Genet 19: 573–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servadio A, Koshy B, Armstrong D, Antalffy B, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY 1995. Expression analysis of the ataxin-1 protein in tissues from normal and spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 individuals. Nat Genet 10: 94–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H, Jafar-Nejad H, Patel AJ, Sun Y, Chen HK, Rose MF, Venken KJ, Botas J, Orr HT, Bellen HJ, et al. 2005. The AXH domain of Ataxin-1 mediates neurodegeneration through its interaction with Gfi-1/Senseless proteins. Cell 122: 633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]