Abstract

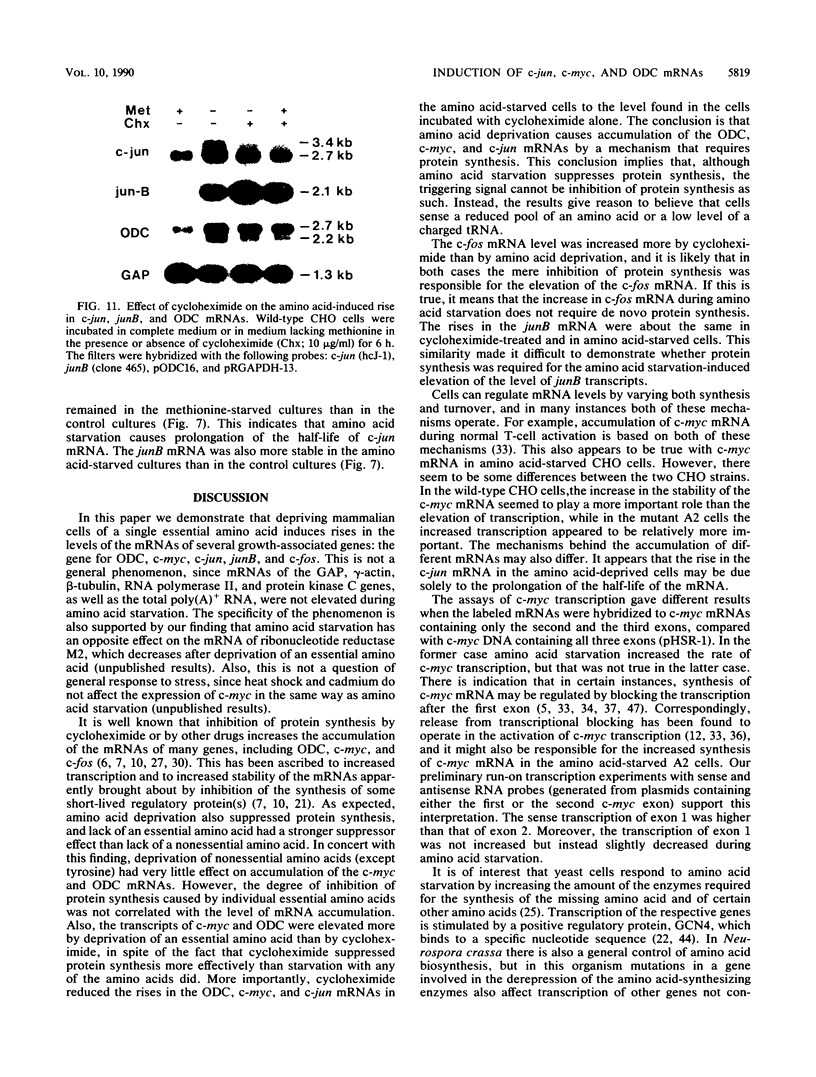

Genes of higher eucaryotic cells are considered to show only a limited response to nutritional stress. Here we show, however, that omission of a single essential amino acid from the medium caused a marked rise in the mRNA levels of c-myc, c-jun, junB and c-fos oncogenes and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) in CHO cells. There was no general accumulation of mRNAs in amino acid-starved cells, since the gamma-actin, beta-tubulin, protein kinase C, RNA polymerase II, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNAs and the total poly(A)+ mRNA were not increased. The levels of c-myc, ODC, and c-jun mRNAs were elevated more by amino acid starvation than by inhibition of protein synthesis with cycloheximide, which is known to increase the levels of these mRNAs. Importantly, however, cycloheximide present during amino acid starvation reduced the rise in the levels of the mRNAs down to the level obtained with cycloheximide alone. This implies that protein synthesis is required for the accumulation of c-myc, ODC, and c-jun mRNAs in amino acid-deprived cells. The junB and c-fos mRNAs, instead, were increased to the same extent or less by amino acid starvation than by cycloheximide treatment. The accumulation of the c-myc mRNA in amino acid-starved cells was due to both stabilization of the mRNA and increase of its transcription. The rise in the c-jun mRNA level seemed to be caused merely by stabilization of the mRNA. Further, despite the inhibition of general protein synthesis, amino acid starvation led to an increase in the synthesis of c-myc polypeptide. The results suggest that mammalian cells have a specific mechanism for registering shortages of amino acids in order to make adjustments compatible with cellular growth.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alitalo K., Bishop J. M., Smith D. H., Chen E. Y., Colby W. W., Levinson A. D. Nucleotide sequence to the v-myc oncogene of avian retrovirus MC29. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Jan;80(1):100–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel P., Allegretto E. A., Okino S. T., Hattori K., Boyle W. J., Hunter T., Karin M. Oncogene jun encodes a sequence-specific trans-activator similar to AP-1. Nature. 1988 Mar 10;332(6160):166–171. doi: 10.1038/332166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel P., Hattori K., Smeal T., Karin M. The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell. 1988 Dec 2;55(5):875–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel P., Imagawa M., Chiu R., Stein B., Imbra R. J., Rahmsdorf H. J., Jonat C., Herrlich P., Karin M. Phorbol ester-inducible genes contain a common cis element recognized by a TPA-modulated trans-acting factor. Cell. 1987 Jun 19;49(6):729–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D. L., Groudine M. A block to elongation is largely responsible for decreased transcription of c-myc in differentiated HL60 cells. Nature. 1986 Jun 12;321(6071):702–706. doi: 10.1038/321702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat N. K., Fisher R. J., Fujiwara S., Ascione R., Papas T. S. Temporal and tissue-specific expression of mouse ets genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 May;84(10):3161–3165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. A., Allfrey V. G. Rapid and reversible changes in nucleosome structure accompany the activation, repression, and superinduction of murine fibroblast protooncogenes c-fos and c-myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Aug;84(15):5252–5256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K. W., Khalili K., Zandomeni R., Weinmann R. The gene encoding the large subunit of human RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1985 Dec 5;260(28):15204–15210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. D. The myc oncogene: its role in transformation and differentiation. Annu Rev Genet. 1986;20:361–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.20.120186.002045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani C., Blanchard J. M., Piechaczyk M., El Sabouty S., Marty L., Jeanteur P. Extreme instability of myc mRNA in normal and transformed human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Nov;81(22):7046–7050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.22.7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eick D., Berger R., Polack A., Bornkamm G. W. Transcription of c-myc in human mononuclear cells is regulated by an elongation block. Oncogene. 1987;2(1):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Gunning P., Kedes L. Human cytoplasmic actin proteins are encoded by a multigene family. Mol Cell Biol. 1982 Jun;2(6):674–684. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.6.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H. J. Changes in gene expression elicited by amino acid limitation in Neurospora crassa strains having normal or mutant cross-pathway amino acid control. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200(2):283–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00425437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort P., Marty L., Piechaczyk M., el Sabrouty S., Dani C., Jeanteur P., Blanchard J. M. Various rat adult tissues express only one major mRNA species from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase multigenic family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985 Mar 11;13(5):1431–1442. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.5.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazin C., Dupont de Dinechin S., Hampe A., Masson J. M., Martin P., Stehelin D., Galibert F. Nucleotide sequence of the human c-myc locus: provocative open reading frame within the first exon. EMBO J. 1984 Feb;3(2):383–387. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M. E., Greene L. A., Ziff E. B. Nerve growth factor and epidermal growth factor induce rapid transient changes in proto-oncogene transcription in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 1985 Nov 15;260(26):14101–14110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan G., Williams B. R. Transcriptional regulation of interferon-responsive genes is closely linked to interferon receptor occupancy. EMBO J. 1986 Jul;5(7):1607–1613. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N., Bishop J. M., Levens D. Regulatory elements that modulate expression of human c-myc. Genes Dev. 1987 Sep;1(7):659–671. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope I. A., Struhl K. GCN4, a eukaryotic transcriptional activator protein, binds as a dimer to target DNA. EMBO J. 1987 Sep;6(9):2781–2784. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölttä E., Pohjanpelto P. Control of ornithine decarboxylase in Chinese hamster ovary cells by polyamines. Translational inhibition of synthesis and acceleration of degradation of the enzyme by putrescine, spermidine, and spermine. J Biol Chem. 1986 Jul 15;261(20):9502–9508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölttä E., Sistonen L., Alitalo K. The mechanisms of ornithine decarboxylase deregulation in c-Ha-ras oncogene-transformed NIH 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1988 Mar 25;263(9):4500–4507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomaa V. V., Pajunen A. E., Bardin C. W., Jänne O. A. Ornithine decarboxylase in mouse kidney. Purification, characterization, and radioimmunological determination of the enzyme protein. J Biol Chem. 1983 Jun 10;258(11):6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänne O. A., Kontula K. K., Isomaa V. V., Bardin C. W. Ornithine decarboxylase mRNA in mouse kidney: a low abundancy gene product regulated by androgens with rapid kinetics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1984;438:72–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb38277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A., Kahana C. Rearrangement between ornithine decarboxylase and the switch region of the gamma 1 immunoglobulin gene in alpha-difluoromethylornithine resistant mouse myeloma cells. EMBO J. 1989 Apr;8(4):1163–1167. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K., Cochran B. H., Stiles C. D., Leder P. Cell-specific regulation of the c-myc gene by lymphocyte mitogens and platelet-derived growth factor. Cell. 1983 Dec;35(3 Pt 2):603–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostura M., Craig N. Treatment of Chinese hamster ovary cells with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D inhibits binding of messenger RNA to ribosomes. Biochemistry. 1986 Oct 21;25(21):6384–6391. doi: 10.1021/bi00369a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land H., Parada L. F., Weinberg R. A. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature. 1983 Aug 18;304(5927):596–602. doi: 10.1038/304596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau L. F., Nathans D. Expression of a set of growth-related immediate early genes in BALB/c 3T3 cells: coordinate regulation with c-fos or c-myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Mar;84(5):1182–1186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. G., Lewis S. A., Wilde C. D., Cowan N. J. Evolutionary history of a multigene family: an expressed human beta-tubulin gene and three processed pseudogenes. Cell. 1983 Jun;33(2):477–487. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W., Mitchell P., Tjian R. Purified transcription factor AP-1 interacts with TPA-inducible enhancer elements. Cell. 1987 Jun 19;49(6):741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90612-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsten T., June C. H., Thompson C. B. Multiple mechanisms regulate c-myc gene expression during normal T cell activation. EMBO J. 1988 Sep;7(9):2787–2794. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechti N., Piechaczyk M., Blanchard J. M., Marty L., Bonnieu A., Jeanteur P., Lebleu B. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of c-myc expression during the differentiation of murine erythroleukemia Friend cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Dec 22;14(24):9653–9666. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.24.9653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. P., Hancock D. C., Littlewood T. D., Evan G. I. A sensitive and quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbence assay for the c-myc and N-myc oncoproteins. Oncogene Res. 1987;2(1):65–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepveu A., Levine R. A., Campisi J., Greenberg M. E., Ziff E. B., Marcu K. B. Alternative modes of c-myc regulation in growth factor-stimulated and differentiating cells. Oncogene. 1987;1(3):243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepveu A., Marcu K. B. Intragenic pausing and anti-sense transcription within the murine c-myc locus. EMBO J. 1986 Nov;5(11):2859–2865. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker P. J., Coussens L., Totty N., Rhee L., Young S., Chen E., Stabel S., Waterfield M. D., Ullrich A. The complete primary structure of protein kinase C--the major phorbol ester receptor. Science. 1986 Aug 22;233(4766):853–859. doi: 10.1126/science.3755547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanpelto P., Hölttä E., Jänne O. A., Knuutila S., Alitalo K. Amplification of ornithine decarboxylase gene in response to polyamine deprivation in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1985 Jul 15;260(14):8532–8537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanpelto P., Hölttä E., Jänne O. A. Mutant strain of Chinese hamster ovary cells with no detectable ornithine decarboxylase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Jun;5(6):1385–1390. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.6.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanpelto P., Virtanen I., Hölttä E. Polyamine starvation causes disappearance of actin filaments and microtubules in polyamine-auxotrophic CHO cells. Nature. 1981 Oct 8;293(5832):475–477. doi: 10.1038/293475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder K., Nathans D. Induction of protooncogene c-jun by serum growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Nov;85(22):8464–8467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. Regulatory sites for his3 gene expression in yeast. Nature. 1982 Nov 18;300(5889):285–286. doi: 10.1038/300284a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. The DNA-binding domains of the jun oncoprotein and the yeast GCN4 transcriptional activator protein are functionally homologous. Cell. 1987 Sep 11;50(6):841–846. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. S. Hybridization of denatured RNA and small DNA fragments transferred to nitrocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Sep;77(9):5201–5205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt P. K., Bos T. J., Doolittle R. F. Homology between the DNA-binding domain of the GCN4 regulatory protein of yeast and the carboxyl-terminal region of a protein coded for by the oncogene jun. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 May;84(10):3316–3319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S., Bishop J. M. DNA sequences that mediate attenuation of transcription from the mouse protooncogene myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jan;86(2):505–509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]