Multiple large-scale analyses in yeast implicate SUMO chain function in the maintenance of higher-order chromatin structure and transcriptional repression of environmental stress response genes.

Abstract

Like ubiquitin, the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) proteins can form oligomeric “chains,” but the biological functions of these superstructures are not well understood. Here, we created mutant yeast strains unable to synthesize SUMO chains (smt3allR) and subjected them to high-content microscopic screening, synthetic genetic array (SGA) analysis, and high-density transcript profiling to perform the first global analysis of SUMO chain function. This comprehensive assessment identified 144 proteins with altered localization or intensity in smt3allR cells, 149 synthetic genetic interactions, and 225 mRNA transcripts (primarily consisting of stress- and nutrient-response genes) that displayed a >1.5-fold increase in expression levels. This information-rich resource strongly implicates SUMO chains in the regulation of chromatin. Indeed, using several different approaches, we demonstrate that SUMO chains are required for the maintenance of normal higher-order chromatin structure and transcriptional repression of environmental stress response genes in budding yeast.

Complete image-based screen data

Introduction

The small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) system plays important roles in many diverse biological processes in all eukaryotes (Johnson, 2004; Kerscher et al., 2006). Like ubiquitin, SUMO modification is effected via covalent conjugation to an epsilon amine moiety of a lysine residue in a targeted protein, via the sequential action of SUMO-specific E1, E2, and E3 proteins. SUMO conjugation can be reversed by a family of SUMO-specific proteases (Johnson, 2004; Kerscher et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2012).

The sole budding yeast SUMO protein is encoded by the essential SMT3 gene. Invertebrates also express a single SUMO protein, whereas vertebrates and plants express multiple SUMO isoforms (Hay, 2005; Castro et al., 2012). Systematic proteomics screens have identified >500 putative SUMO conjugates in budding yeast (among others, Wohlschlegel et al., 2004; Denison et al., 2005; Cremona et al., 2012) and hundreds more in plants, insects, and mammals (Nie et al., 2009; Elrouby and Coupland, 2010; Bruderer et al., 2011). Ectopic expression of the human SUMO-1 protein rescues smt3 lethality (Takahashi et al., 1999), highlighting the usefulness of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model organism for assessing SUMO function in eukaryotes.

The SUMO proteins interact with small hydrophobic domains referred to as SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs). SIMs confer low affinity binding to SUMOs, often occur in tandem, and can confer specificity for particular SUMO isoforms (Prudden et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2008; Tatham et al., 2008). Sumoylation thus represents a rapid and efficient way to regulate protein–protein interactions. SUMO–SIM interactions have been implicated in a variety of biological functions, including transcriptional control (Ouyang et al., 2009; Santiago et al., 2009; Saether et al., 2011), DNA damage repair (Li et al., 2010; Galanty et al., 2012; Yin et al., 2012), protein degradation (Prudden et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2008), and the assembly of DNA–protein superstructures such as PML (Lallemand-Breitenbach et al., 2008; Tatham et al., 2008) and insulator bodies (MacPherson et al., 2009; Golovnin et al., 2012).

Notably, SUMO can be conjugated to proteins in a monomeric form, or as oligomeric SUMO “chain” structures. In budding yeast, SUMO–SUMO linkages are formed primarily via K15 (Bencsath et al., 2002), although we and others have detected linkages at additional lysine residues in vitro (Bencsath et al., 2002; Jeram et al., 2010). The best characterized function of SUMO chains is as a secondary degradation signal. The SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) are an evolutionarily conserved family of ubiquitin E3 proteins that contain multiple SIMs. The STUbLs are thus recruited to polysumoylated proteins and effect their ubiquitylation, marking them for 26S proteasome-mediated destruction (Perry et al., 2008). A few STUbL targets have been identified, including PML (Lallemand-Breitenbach et al., 2008; Tatham et al., 2008), the HTLV-1 Tax protein (Fryrear et al., 2012), the Drosophila melanogaster transcriptional repressor Hairy (Abed et al., 2011), and the budding yeast transcriptional regulator Mot1 (Wang et al., 2006; Wang and Prelich, 2009). Importantly, however, the biological functions of SUMO chains remain poorly characterized.

Many studies have implicated the SUMO system in transcriptional regulation (Garcia-Dominguez and Reyes, 2009; Abed et al., 2011). Transcription factors and coregulators, chromatin remodeling proteins, and histones are all modified by SUMO (Shiio and Eisenman, 2003; Nathan et al., 2006). Most studies have indicated that SUMO plays a negative regulatory role in transcription, and SUMOs can bind to SIMs in transcriptional co-repressors such as CoREST1 (Ouyang et al., 2009) and Daxx, and other types of proteins that regulate chromatin structure, including histone methyltransferases (SETDB1, SUV4-2OH) and the chromatin remodeler Mi2 (Ivanov et al., 2007; Stielow et al., 2008a,b), possibly to effect local heterochromatization (Ross et al., 2002; Yang and Sharrocks, 2004; Ivanov et al., 2007).

Here, using a combination of high-content microscopic screening, functional genomics analysis, and high-density transcript profiling, we conducted the first global study of SUMO chain function. Using this data-rich resource, we implicate the SUMO system in the maintenance of transcriptional repression and higher-order chromatin structure.

Results

smt3allR strains exhibit chromosome segregation defects and replication-associated DNA damage

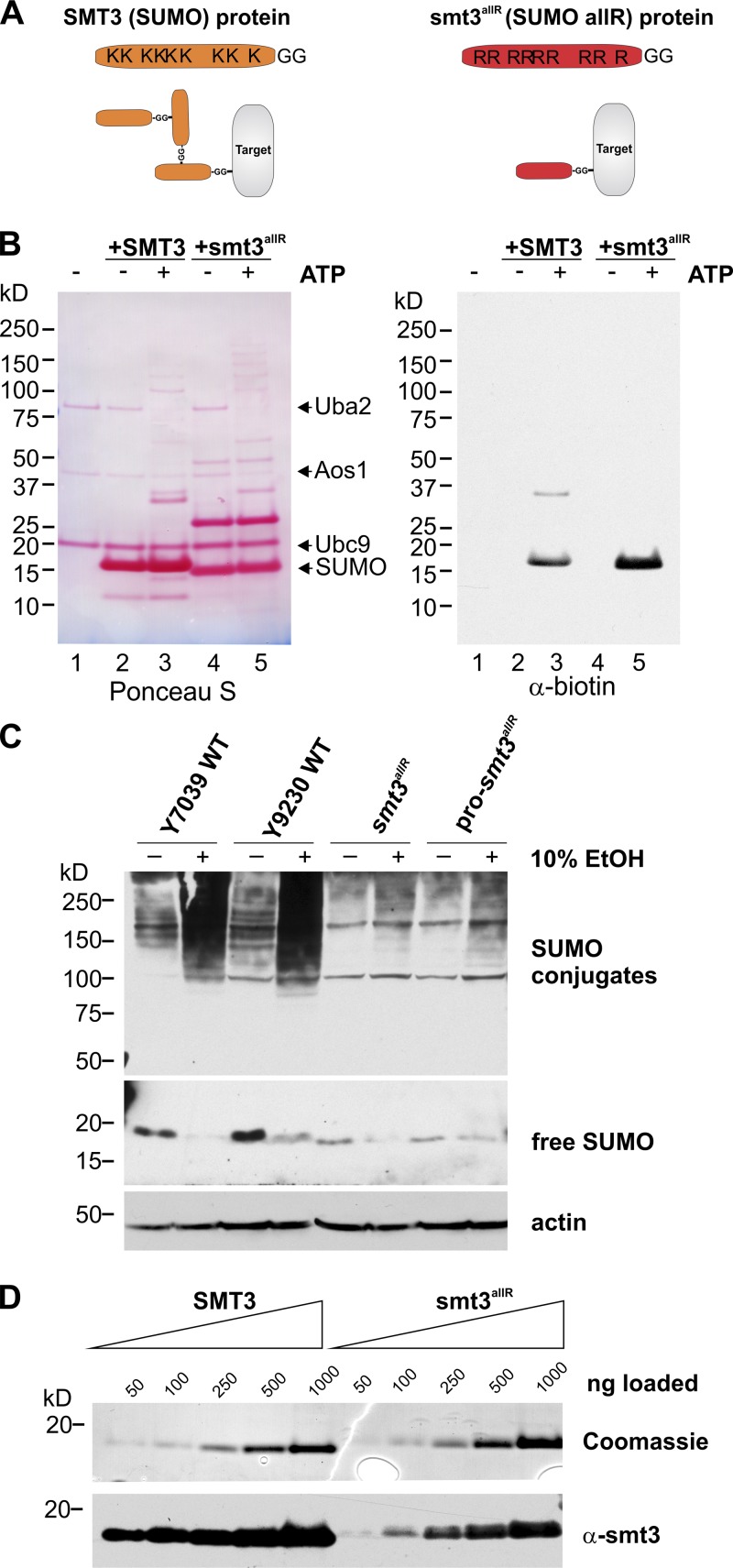

To better understand the biological roles of SUMO chains, we generated haploid yeast strains in which the endogenous SUMO gene (SMT3) was replaced by an ORF in which all nine lysine codons were mutated to code for arginine (as in Bylebyl et al., 2003). The resulting mutant SUMO “allR” polypeptide can thus be conjugated to other proteins as a monomer, but lacks the ability to form SUMO chains (Fig. 1 A). Although smt3 deletants arrest in G2/M with short spindles and replicated DNA (Seufert et al., 1995; Li and Hochstrasser, 1999; Hochstrasser, 2000), an earlier study demonstrated that smt3allR strains are viable and that the SUMO allR polypeptide is conjugated to the septin protein Cdc11 in vivo (Bylebyl et al., 2003). SUMO function is thus at least partially fulfilled by the SUMO allR protein. Consistent with these data, we found that a recombinant SUMO allR protein is conjugated to a model substrate (a biotinylated 11-aa peptide containing the SUMO consensus sequence) in vitro as efficiently as the wild-type (WT) protein (Fig. 1 B), which indicates that the K-to-R mutations do not appreciably affect the ability of this polypeptide to be recognized by the SUMO E1 or E2 proteins.

Figure 1.

A SUMO allR polypeptide can be conjugated to target proteins, but is unable to form SUMO chains in vitro and in vivo. (A) Schematic representation of the WT SUMO and SUMO allR proteins. Although both SUMO protein variants can be covalently conjugated to substrates (also known as “target” proteins), the allR SUMO polypeptide lacks lysine residues, and is therefore unable to form SUMO chains. (B) WT SUMO and the SUMO allR protein are conjugated to a biotinylated polypeptide (a model substrate containing the sumoylation consensus sequence) at similar efficiencies in vitro. Reactions were conducted in the presence (+) and absence (−) of ATP. (Lane 1) SUMO E1 and E2 proteins, along with the biotinylated substrate peptide (reaction mix). (Lanes 2 and 3) Reaction mix plus WT SUMO protein. (Lanes 4 and 5) Reaction mix plus allR SUMO protein. (C) smt3allR strains do not form high-molecular-weight SUMO conjugates in response to environmental stress. WT and smt3allR cells were exposed to 10% ethanol (EtOH) for 1 h, and SUMO conjugates were visualized by Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates. Unconjugated SUMO is shown in the middle panel (a longer exposure of the same Western blot), and actin (loading control) in the bottom panel. The pro-smt3allR strain expresses a SUMO allR pro-protein, which possesses three additional C-terminal residues that must be cleaved to generate the mature SUMO protein. The smt3allR strain expresses a mature form of the allR SUMO protein. (D) The SUMO antibody does not detect the SUMO allR protein with the same efficiency as the WT SUMO polypeptide. Equal amounts of purified recombinant SUMO WT and allR proteins were subjected to Coomassie blue staining (top) and Western blotting (bottom).

Several previous studies have demonstrated that steady-state sumoylation increases in response to stress (Zhou et al., 2004; Tempé et al., 2008). To determine whether the smt3allR strain is able to respond to environmental stresses commonly encountered by yeast, we assessed its response to high ethanol (EtOH) concentrations. As expected, exposure of WT cells to 10% EtOH (for 1 h) led to a dramatic increase in high-molecular-weight SUMO conjugates (Fig. 1 C). Although smt3allR cells displayed a decrease in unconjugated (free) SUMO, only a very minor increase in high-molecular-weight SUMO conjugates in response to EtOH treatment was observed (Fig. 1 C; the minor high molecular signal most likely reflects multi-monosumoylation of high-molecular-weight targets, or could represent, e.g., proteins that are both sumoylated and ubiquitylated in response to stress). In addition, here we tested two different smt3allR strains: one in which the C-terminal three amino acid extension of the SUMO protein was maintained in the coding region (pro-smt3allR) and a second in which this region was removed to express the mature SUMO polypeptide (smt3allR). No differences in division time (not depicted) or EtOH response were observed between the two strain types (Fig. 1 C), which indicates that SUMO maturation activity is not limiting in these cells.

The signal strength of the unconjugated SUMO allR protein in Western blot analysis was markedly lower than that observed for the endogenous WT SUMO protein (Fig. 1 C). However, when equal amounts of purified recombinant WT and allR SUMO polypeptides were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 1 D, top) or Western blotting analysis (Fig. 1 D, bottom), we found that the allR SUMO protein is simply not recognized as efficiently by the SUMO antibody (with this antibody, the allR protein yields <20% of the signal intensity of an equivalent amount of the WT SUMO protein). Indeed, quantification of SUMO signal intensity in parental and smt3allR yeast strains based on these data indicate that the SUMO allR protein is expressed at levels similar to (or even higher than) the endogenous SUMO protein (see Materials and methods for details).

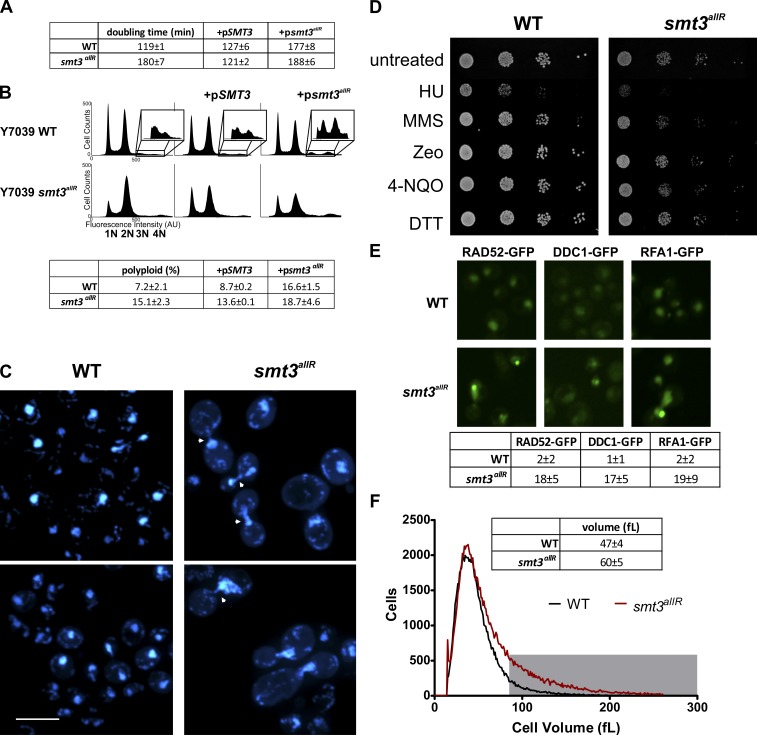

As expected (Bylebyl et al., 2003), under standard culture conditions the doubling time of smt3allR cells is increased ∼1.5-fold (180 ± 6.7 min) as compared with parental strains (119 ± 1.3 min; P < 0.01; Fig. 2 A). FACS of SYTOX green–stained cells revealed a slight increase in a supra-G2 population, and an approximately twofold increase in cells with >2n DNA content (Fig. 2 B) in the smt3allR cell population (P < 0.01). Consistent with observations in other SUMO pathway mutants (Felberbaum and Hochstrasser, 2008; Lee et al., 2011), DAPI staining revealed chromosome segregation defects in a subset of the smt3allR population (∼40% of large budded cells; Fig. 2 C and Fig. S1 A). A lack of SUMO chain synthesis thus appears to negatively affect the efficient segregation of chromosomes, which in turn leads to an increase in population ploidy.

Figure 2.

smt3allR mutant yeast strains display increased doubling time, chromosome segregation defects, and increased ploidy, and are sensitive to DNA replication inhibitors. (A) Doubling time (mean ± SD) was measured over an 8-h period of log-phase growth for smt3allR and parental strains. Strains (as indicated) were also transfected with a galactose-inducible SMT3 (WT) or smt3allR plasmid (+pSMT3 or +psmt3allR, respectively), which was induced for 18 h before the first doubling time measurement. (B) FACS analysis of untransfected parental and smt3allR strains, and the same strains expressing the WT or allR SUMO proteins (as in A). DNA was stained with SYTOX green and data were collected on 50,000 events. The insets highlight the polyploid (>2n) population in each analysis. (C) Parental and smt3allR strains were stained with DAPI and imaged using confocal microscopy. Two representative images from each strain are shown. Cells displaying abnormal chromosome segregation are highlighted with arrowheads. Bar, 10 µm. (D) Log-phase cells were treated as indicated for 1 h, serially diluted (10×), and spotted onto YPD plates (HU, hydroxyurea; MMS, methyl methanesulfonate; Zeo, zeocin; 4-NQO, 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide; DTT, dithiothreitol; Linger and Tyler, 2005; Rand and Grant, 2006; Tang et al., 2009). Colonies were grown for 2 d at 30°C. (E) Spontaneous DNA damage foci were quantified in parental and smt3allR strains using GFP-tagged RAD52, DDC1, and RFA1. The mean number of foci (±SD) from four fields is tabulated. Bar, 10 µm. (F) Cell size distribution (mean ± SD) was measured on a Z2 counter (Beckman Coulter), as in Jorgensen et al. (2002). The gray box highlights the cell population with a volume >80 fL in the parental (black line) and smt3allR (red line) strains. Data shown are from a single representative experiment, conducted twice.

Consistent with a role for SUMO chains in DNA replication, smt3allR cells also displayed hypersensitivity to the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor hydroxyurea (HU) and the alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), but did not exhibit increased sensitivity to DNA damage induced by zeocin or 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4NQO; Fig. 2 D and Fig. S1 B), and did not display increased sensitivity to high or low temperatures, or protein-damaging agents (Fig. 2 D and Fig. S1, B and C).

Strikingly, untreated smt3allR strains displayed a >10-fold increase in the number of steady-state DNA damage foci, as visualized via RAD52-GFP, DDC1-GFP, and RFA1-GFP (parental strain average for all markers = 1.51 ± 0.63 foci/field; smt3allR average = 17.1 ± 2.93 foci/field; Fig. 2 E). To further explore the role of SUMO chains in replication-associated DNA damage, we crossed the smt3allR strain with 384 yeast strains expressing GFP-tagged proteins (Huh et al., 2003) previously linked to the DNA damage response (Tkach et al., 2012). Live cells were imaged using automated high-throughput confocal microscopy (Tkach et al., 2012) and the resulting images were examined for differences in localization and signal intensity in the SUMO chain mutant (Table 1 and Table S1). This high content screen (HCS) highlighted changes in localization and/or intensity in smt3allR cells for 144 proteins, most of which are involved in DNA replication, segregation, or repair processes (Table 1 and Table S1). These data are consistent with several earlier publications linking the SUMO system to replication stress (Branzei et al., 2006; Xiong et al., 2009), yet significantly expand the repertoire of DNA damage–associated proteins demonstrated to be affected in response to SUMO system defects. Most importantly, these data for the first time also specifically implicate SUMO chains in this function.

Table 1.

smt3allR HCS

| Group | Protein | ||||||||

| DNA replication and repair | AQR1 | DPB11 | HST4 | MGS1 | NUP53 | RAD59 | RPL40A | SLD3 | XRS2 |

| CGR1 | DUN1 | IPL1 | MKT1 | PNC1 | RFA1 | RPN4 | SLX4 | YDL156W | |

| DBF4 | DUS3 | LCD1 | MRE11 | RAD50 | RFA2 | SAE2 | STP1 | YJR056C | |

| DDC1 | GLN1 | MCM2 | MRS6 | RAD52 | RFC2 | SGF11 | TRM112 | YML108W | |

| DNA2 | SRS2 | MCM4 | MSN2 | RAD57 | RNR4 | SGS1 | TSR1 | ZPR1 | |

| Polarization/budding/bud site selection | BUD14 | GSP2 | MSB1 | NBA1 | CDC24 | GYL1 | MSB3 | OPY2 | |

| Ion homeostasis (pH) | ARN1 | CTR1 | VMA10 | VMA4 | YLR126C | YOL092W | CRD1 | POR1 | VMA2 |

| VPH1 | YML018C | ||||||||

| mRNA catabolic processes | DCP1 | EDC2 | LSM1 | LSM3 | LSM7 | NMD4 | PBP4 | DHH1 | EDC3 |

| LSM2 | LSM4 | NAM7 | PAT1 | ||||||

| Spindle defects | ASE1 | DAD3 | CNM67 | DAD4 | |||||

| Vacuole function | LAP4 | PEP8 | VPS1 | YLR297W | MTC5 | PIB1 | YIR014W | ||

| Ribosome biogenesis | ATC1 | CMS1 | GDT1 | NOP13 | RMT2 | ATG29 | ECM1 | HGH1 | NOP58 |

| RPL7B | |||||||||

| Stress response | AHA1 | CUE1 | HSP42 | ITR1 | TSA1 | YKL069W | APJ1 | GSY2 | HXT3 |

| SCH9 | WSC4 | ||||||||

| Cell shape defects | DSE3 | NEO1 | SEC10 | SEC6 | VPS41 | FLC1 | RAS1 | SEC3 | SEC8 |

| Other | ATG16 | FAT1 | KTR3 | PBY1 | PPH21 | SRP68 | YDL085C-A | YGR042W | YKR011C |

| CHS7 | HOM6 | LSB1 | PEX21 | RSM10 | YBR259W | YDR090C | YHR140W | YLR363W-A | |

| FAA1 | IRC22 | MDM12 | PIL1 | SGT2 | YDC1 | YDR170W-A | YIL108W | YMR111C | |

144 GFP-tagged proteins displayed a change in localization and/or intensity when expressed in the smt3allR mutant grown in rich medium. Proteins are grouped according to ten functional categories.

SMT3 was first characterized as a high-copy suppressor of mif2, a kinetochore protein required for structural integrity of the mitotic spindle (Meluh and Koshland, 1995; Vizeacoumar et al., 2010). Chromosomal passenger complex protein localization is also regulated by the SUMO system, to mediate spindle disassembly (Vizeacoumar et al., 2010). Consistent with a role for SUMO chains in mitotic spindle dynamics, the HCS highlighted mislocalization of several additional proteins (4 of 11 proteins in the screen) involved in spindle function (Table 1 and Fig. S2).

Also of note, although a majority of cells fell within the normal size range, a subpopulation of smt3allR cells exhibited significant increases in volume (P < 0.001; Fig. 2 F). The proportion of cells with a volume >80 fl (more than two standard deviations from the mean) was 11 ± 4% for parental strains and 30 ± 6% for smt3allR strains. Both large and normal sized smt3allR cells successfully produced colonies, and gave rise to a mix of normal and large cells in similar proportions (unpublished data), which indicates that the large cell phenotype is neither terminal nor heritable. The size increase thus likely reflects a cell cycle delay caused by an increased DNA repair load and chromosome segregation defects.

smt3allR cells display characteristics of an activated environmental stress response

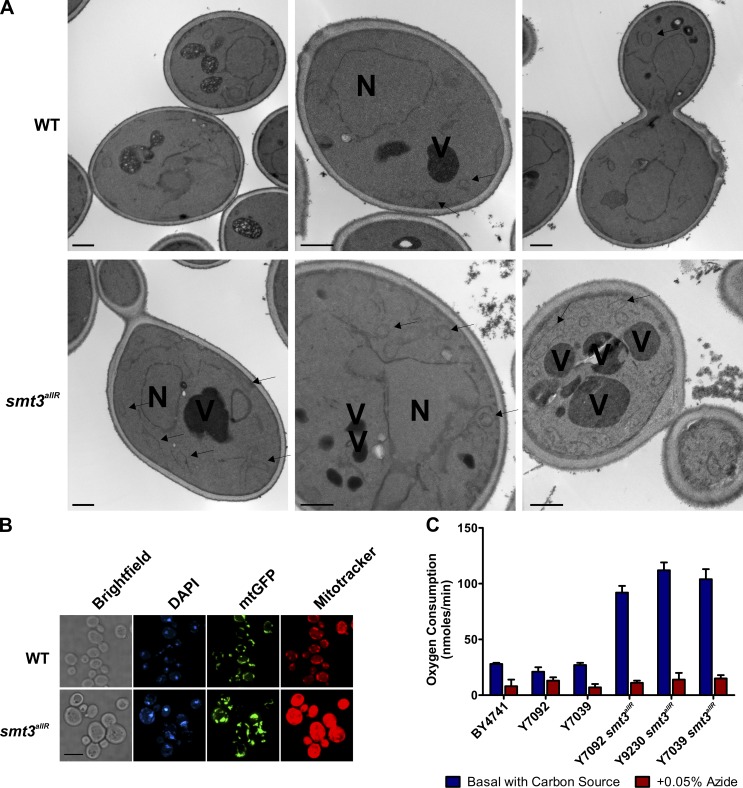

The HCS also highlighted several GFP-tagged vacuolar proteins with clear changes in localization in smt3allR cells; e.g., VPS1-GFP and VPS41-GFP displayed more numerous puncta than parental cells (Fig. S2). Multiple mitochondrial markers (e.g., MDM12-GFP and POR1-GFP) also displayed markedly increased signal intensity in the smt3allR strains (Fig. S2). Consistent with these data, electron micrographs revealed a large subset of smt3allR cells with fragmented vacuoles, increased mitochondrial volume, and thicker cell walls than parental strains (Fig. 3 A and Fig. S3 A). These defects were unexpected and were investigated further.

Figure 3.

Ultrastructural characterization of smt3allR mutant strains. (A) Electron micrographs of parental and smt3allR cells, highlighting the nucleus (N), vacuoles (V), and mitochondria (arrowheads). Bars, 500 nm. (B) Mitochondrial-targeted GFP (mtGFP) and MitoTracker red CMXRos staining highlight increased mitochondrial volume in smt3allR mutant cells. (C) Basal oxygen consumption of parental and smt3allR mutant cells (error bars indicate mean ± SD) grown in YPD. Azide treatment inactivates oxidative respiration and indicates levels of nonmitochondrial oxygen consumption.

Signal intensities for a GFP bearing a mitochondrial targeting sequence (Westermann and Neupert, 2000) and Mitotracker red, a thiol-reactive dye that accumulates in active mitochondria, were strikingly enhanced in cells defective for SUMO chain synthesis (Fig. 3 B). smt3allR cells also exhibited a significant increase (more than fourfold; P < 0.01) in basal oxygen consumption rates (Fig. 3 C), even when maintained in glucose-containing culture media (a condition in which glycolysis is the preferred mode of energy production). smt3allR cells thus maintain abnormally high levels of mitochondria that are metabolically active even in the presence of glucose.

Vacuolar fragmentation is observed in cells in a hypertonic environment (Ryan et al., 2008). Glycerol is the primary osmoprotectant in S. cerevisiae, and is synthesized in response to hyperosmotic conditions to maintain cell turgor (Hohmann, 2009). smt3allR cells grown in isosmotic media displayed highly fragmented vacuoles and a more than twofold increase (P < 0.01) in intracellular glycerol concentrations, as compared with parental strains (Fig. S3, B and C). These data suggest that SUMO chain mutants are also subject to chronic osmotic stress or exhibit aberrant osmotic stress signaling.

Together, our data reveal that disruption of SUMO chain assembly gives rise to a pleiotropic cell population exhibiting several different physiological defects. We did not observe any clear correlation between, e.g., ploidy and the number of DNA damage foci or mitochondrial mass, which suggests that these phenotypes are largely independent of one another.

Replication-associated DNA damage is observed in other types of SUMO system mutants (Branzei et al., 2006; Schwartz et al., 2007), and our analysis implicates SUMO chains in this process. However, we also observed phenotypic characteristics in smt3allR cells that have not previously been described for other types of SUMO mutants. Many of these traits are reminiscent of an inappropriately activated response to environmental stress or nutrient-poor media conditions.

The smt3allR phenotype is caused by a lack of SUMO chains

To confirm that the smt3allR phenotype is caused by a lack of SUMO chains, and not to secondary mutations that could arise in such mutants, we transformed plasmids coding for galactose-inducible WT or allR SUMO proteins into parental and smt3allR strains, and assessed their effects on doubling time, ploidy, and vacuolar morphology. Additional SUMO allR protein expression in the smt3allR strain (induced for 16 h) had no apparent effect on cycling time (188 ± 6 min), ploidy, or vacuole size and number (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S3 D). Similarly, overexpression of the WT SUMO protein in parental strains had no discernible effect on these phenotypic features (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S3 D). However, overexpression of the SUMO allR protein in parental (WT) strains led to a significant increase in doubling time (177 ± 8 min, P < 0.001; Fig. 2 A), an increase in the number of cells with >2n DNA ploidy (Fig. 2 B), and an increase in vacuolar fragmentation (Fig. S3 D). Conversely, expression of the WT SUMO protein in smt3allR strains led to a decrease in doubling time (121 ± 2 min, P < 0.001), a decrease in the proportion of cells with >2n DNA ploidy, and a decrease in vacuolar fragmentation (Fig. 2, A and B; and Fig. S3 D). The smt3allR phenotype can thus be at least partially rescued by expression of a SUMO protein that can form chains, and overexpression of the SUMO allR protein in WT cells can effect changes in cycling time, ploidy, and vacuolar morphology even in the presence of the endogenous SUMO polypeptide. Together, these data indicate that the smt3allR phenotype is not caused by a limited supply of the SUMO protein for conjugation, or to secondary mutations in these strains, but is indeed caused by a lack of SUMO chains. These data also demonstrate that the SUMO allR protein can act in a dominant manner in the presence of the endogenous SUMO polypeptide, presumably by preventing SUMO chain formation.

Previous studies have indicated that SUMO chains in vivo are linked primarily via N-terminal lysine residues (mostly through K15; Bencsath et al., 2002). To determine whether the smt3allR phenotype could be recapitulated by disrupting only the N-terminal lysine residues, we also expressed a SUMO 3KR mutant (in which only lysines 11, 15, and 19 are mutated to arginine residues) in WT cells. Division time and ploidy were indistinguishable from cells expressing the SUMO allR mutant (Fig. S4), which further suggests that the smt3allR phenotype is caused by the disruption of SUMO chains. In the remaining work presented here, we used smt3allR strains to avoid any possibility of SUMO chain synthesis via the use of alternative lysine residues (as we and others have observed in vitro; Bencsath et al., 2002; Bylebyl et al., 2003; Jeram et al., 2010).

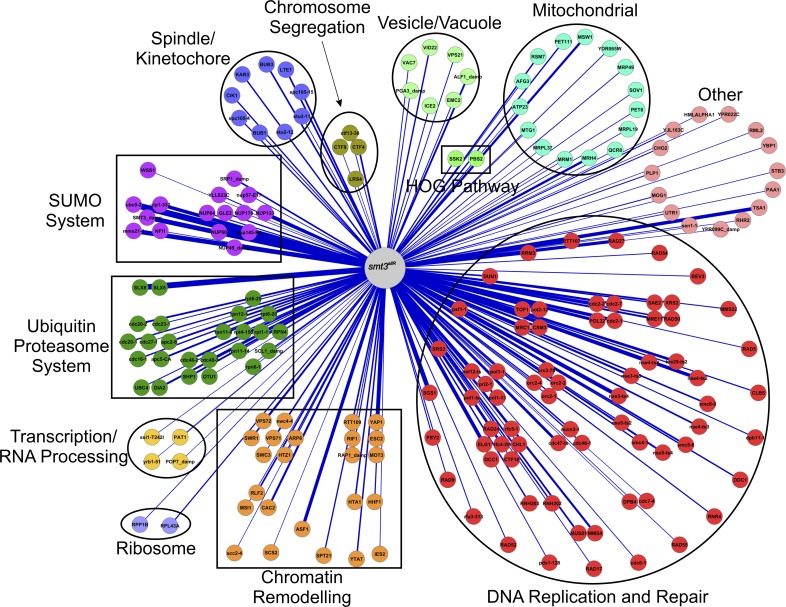

A SUMO chain genetic interaction network

To identify cellular pathways that specifically compensate for disrupted SUMO chain synthesis, the smt3allR strain was subjected to synthetic genetic array (SGA) analysis, as in Makhnevych et al. (2009) and Costanzo et al. (2010). The smt3allR mutant was crossed with an ordered array of ∼4,700 viable yeast deletion mutants, and the resulting strains were scored for colony growth (Baryshnikova et al., 2010). To avoid the possibility of false-positive interactions caused by secondary mutations in the SUMO chain mutant, SGA was conducted twice, using two different smt3allR strains (one expressing pro-SMT3allR and one expressing the mature SMT3allR polypeptide, as in Fig. 1 C). 149 high-confidence synthetic genetic interactions were detected in both analyses (Table S2). The resultant SUMO chain genetic interaction network represents the first global genetic analysis of SUMO chain function in any organism. Gene ontology (GO) analysis (Table S2) highlighted significant enrichment in interactions with genes involved in DNA replication, DNA damage repair, chromatin remodeling, cell cycle control, stress responses, protein catabolism, nuclear transport, and meiosis.

SGA correlation analysis (i.e., the comparison of genetic interaction maps) is useful for gaining insight into the function of a gene of interest, because genes that share similar patterns of genetic interactions are likely to share similar biological roles (Costanzo et al., 2010). The smt3allR SGA profile was thus compared with SGA-derived genetic interaction profiles of 4,458 mutant strains available in the data repository of the yeast genetic interactions database (DRYGIN; Koh et al., 2010). 194 genes displayed a significant positive correlation with the smt3allR genetic interaction map (Fig. 4, Table 2, and Table S2). Attesting to the robustness of this analysis, three of the four highest correlated genes were derived from components of the SUMO system itself: ubc9 (ubc9-2), mms21 (mms21-sp), and smt3 (smt3-damp; decreased abundance by mRNA perturbation; Yan et al., 2008). ulp1 was also a top-scoring hit (ulp1-333). Likely reflecting a role in a subset of SUMO functions, siz2 (nfi1) displayed a significant, but lower, overlap with the smt3allR interaction profile. Consistent with STUbL-mediated degradation as a major function for SUMO chains, the second most highly correlated genetic interaction map in our screen was slx8. The gene coding for its binding partner slx5 was also a top-scoring hit.

Figure 4.

smt3allR SGA correlation analysis. 194 genes yielded a significant positive correlation with the smt3allR genetic interaction network. Edge width corresponds to correlation values.

Table 2.

smt3allR SGA correlation analysis

| Category | Gene | Correlation |

| SUMO system | ||

| SUMO system components | ubc9-2 | 0.430 |

| SMT3_damp | 0.338 | |

| mms21-1 | 0.329 | |

| ulp1-333 | 0.263 | |

| NFI1 | 0.087 | |

| NPC components–Ulp1 localization | NUP60 | 0.328 |

| NUP133 | 0.228 | |

| nup145-R4 | 0.223 | |

| SRP1_damp | 0.149 | |

| NUP84 | 0.113 | |

| GLE2 | 0.130 | |

| YLL023C | 0.109 | |

| nup57-E17 | 0.094 | |

| NUP49_damp | 0.091 | |

| Chromatin remodeling | ||

| Histone chaperone | ASF1 | 0.247 |

| Chromatin silencing | ESC2 | 0.294 |

| RTT109 | 0.141 | |

| RAP1_damp | 0.116 | |

| MOT3 | 0.110 | |

| YAP1 | 0.109 | |

| RIF1 | 0.099 | |

| Chromatin assembly factor (CAF-1) | CAC2 | 0.176 |

| RLF2 | 0.148 | |

| MSI1 | 0.090 | |

| Histones | HTA1 | 0.139 |

| HTZ1 | 0.123 | |

| HHF1 | 0.119 | |

| SWR1 complex | SWR1 | 0.144 |

| HTZ1 | 0.123 | |

| VPS71 | 0.108 | |

| ARP6 | 0.105 | |

| swc4-4 | 0.099 | |

| VPS72 | 0.098 | |

| SWC3 | 0.097 | |

| DNA replication and repair | ||

| MRX complex | MRE11 | 0.166 |

| XRS2 | 0.154 | |

| RAD50 | 0.138 | |

| SAE2 | 0.127 | |

| MCM complex | cdc47-ts | 0.217 |

| mcm3-1 | 0.132 | |

| cdc46-1 | 0.127 | |

| Mms21–Smc5–Smc6 complex | mms21-1 | 0.329 |

| nse3-ts4 | 0.287 | |

| nse4-ts2 | 0.263 | |

| kre29-ts2 | 0.213 | |

| nse4-ts4 | 0.183 | |

| nse3-ts3 | 0.175 | |

| nse5-ts4 | 0.165 | |

| smc5-6 | 0.152 | |

| nse4-ts3 | 0.151 | |

| smc6-9 | 0.147 | |

| nse5-ts2 | 0.118 | |

| Pol2–TOF1–MRC1–CSM3 complex | MRC1 | 0.206 |

| pol2-12 | 0.182 | |

| CSM3 | 0.180 | |

| TOF1 | 0.141 | |

| Origin recognition complex | orc2-2 | 0.157 |

| orc2-4 | 0.096 | |

| orc3-70 | 0.095 | |

| Ribonuclease 2 | RNH203 | 0.138 |

| RNH202 | 0.137 | |

| Polymerase delta | POL32 | 0.231 |

| cdc2-1 | 0.219 | |

| cdc2-7 | 0.185 | |

| cdc2-2 | 0.167 | |

| Mms4–Mus81 complex | MMS4 | 0.177 |

| MUS81 | 0.156 | |

| Pol1-DNA primase | pol12-ts | 0.192 |

| pol1-13 | 0.128 | |

| pol1-ts | 0.120 | |

| pol1-1 | 0.118 | |

| pri2-1 | 0.109 | |

| RFC complex | ELG1 | 0.271 |

| rfc4-20 | 0.214 | |

| rfc5-1 | 0.153 | |

| RAD24 | 0.116 | |

| CTF18 | 0.101 | |

| CHL1 | 0.097 | |

| DCC1 | 0.092 | |

| Other | RAD27 | 0.242 |

| RRM3 | 0.192 | |

| RTT107 | 0.168 | |

| psf1-1 | 0.158 | |

| DUN1 | 0.146 | |

| DDC1 | 0.133 | |

| RNR4 | 0.120 | |

| CLB5 | 0.119 | |

| RAP1_damp | 0.116 | |

| dpb11-1 | 0.111 | |

| MMS22 | 0.108 | |

| RAD5 | 0.100 | |

| RAD54 | 0.098 | |

| REV3 | 0.098 | |

| RAD17 | 0.097 | |

| cdc6-1 | 0.097 | |

| RAD55 | 0.090 | |

| Ubiquitin–proteasome system | ||

| STUbL | SLX8 | 0.393 |

| SLX5 | 0.247 | |

| Cdc48 | cdc48-2 | 0.183 |

| SHP1 | 0.160 | |

| cdc48-3 | 0.145 | |

| OTU1 | 0.081 | |

| APC/C | apc5-CA | 0.162 |

| apc2-8 | 0.161 | |

| cdc20-2 | 0.161 | |

| cdc20-1 | 0.134 | |

| cdc16-1 | 0.130 | |

| cdc23-1 | 0.102 | |

| SCF | DIA2 | 0.169 |

| UBC4 | 0.105 | |

| Proteasome | rpn12-1 | 0.155 |

| rpn11-8 | 0.127 | |

| SCL1_damp | 0.118 | |

| rpn11-14 | 0.107 | |

| rpt1-1 | 0.107 | |

| RPN4 | 0.100 | |

| rpt6-20 | 0.091 | |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Spindle/kinetochore | spc105-15 | 0.154 |

| LTE1 | 0.152 | |

| BUB3 | 0.149 | |

| KAR3 | 0.135 | |

| CIK1 | 0.129 | |

| CLB5 | 0.119 | |

| BUB1 | 0.105 | |

| stu2-12 | 0.094 | |

| stu2-11 | 0.092 | |

| HOG pathway signaling | SSK2 | 0.120 |

| PBS2 | 0.082 | |

| Vesicle/vacuole | ALF1_damp | 0.160 |

| LTE1 | 0.152 | |

| VID22 | 0.133 | |

| ICE2 | 0.105 | |

| PGA3_damp | 0.104 | |

| EMC2 | 0.102 | |

| VPS21 | 0.101 | |

| Mitochondrial function | MRH4 | 0.193 |

| MSW1 | 0.187 | |

| PET111 | 0.131 | |

| MRP49 | 0.100 | |

| YDR065W | 0.100 | |

| PET8 | 0.092 | |

| SOV1 | 0.092 | |

| QCR8 | 0.090 | |

| MRPL19 | 0.090 |

194 genes display a positive correlation with the smt3allR genetic map. Genes are grouped according to functional categories.

As expected, ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) components were also highlighted in this analysis; the UPS works with Slx5-Slx8 to effect SUMO-targeted protein degradation. We also observed overlap with the cdc48 (p97) SGA map. This protein was recently reported to work with the Slx5-Slx8 proteins to mediate genome stability (Nie et al., 2012). Another set of highly correlated genes corresponded to nuclear pore complex (NPC) components and karyopherins (nup60, nup133, nup145-R4, nup84, and srp1-damp). This is also not unexpected, as strains with a loss of function in any of these genes display aberrant Ulp1 localization, which directly impacts SUMO system function (Panse et al., 2003; Makhnevych et al., 2007).

Consistent with the smt3allR phenotype, several proteins involved in DNA replication and repair shared significant similarity with the smt3allR genetic interaction profile, including several DNA polymerases, helicases, and exonucleases (e.g., rad27, cdc2-1, pol32, pol12-ts, pol1-13, rrm3, etc.), and genes implicated in stalled replication fork stabilization (e.g., tof1, mrc1, and csm3, and the MCM helicase complex: mcm3-1, cdc47-ts, and cdc46-1). Recent work has also demonstrated that the SUMO E3 ligase Mms21, as part of the Smc5-6 complex, plays a critical role in resolving recombination intermediates at damaged DNA templates (Branzei et al., 2006; Chavez et al., 2010). Smc5-6 mutants undergo aberrant mitosis, in which chromosome segregation of repetitive regions is impaired (Torres-Rosell et al., 2005). A failure to resolve this type of DNA damage can lead to chromosomal rearrangements and increased ploidy. Indeed, multiple components of the Smc5-Smc6 complex (mms21-1, nse3-ts4, nse4-ts2, kre29-ts2, etc.) were highly correlated in our analysis. Also as observed in our HCS, genetic interaction maps for esc2, sgs1, mus84, and mms1, all of which play an important role in resolving homologous recombination repair DNA intermediates in response to replication stress (Ashton and Hickson, 2010; Rossi et al., 2010; Hickson and Mankouri, 2011), were highly correlated with the smt3allR interaction map.

Notably, SGA correlation analysis also highlighted similarity between smt3allR and several proteins involved in chromatin organization and remodeling. For example, significant correlations were observed with the histone chaperone asf1, several components of chromatin assembly factor-1 (CAF-1; cac2, rlf2, and msi1), the histone acetyltransferase rtt109, the histone H2A.Z exchange complex SWR1 (swr1, vps71, arp6, swc4-4, etc.), histone deletants (hta1, htz1, hhf1), and spt21 (required for proper histone gene transcription).

Interestingly, we also observed similarity with genes implicated in mitochondrial function (e.g. mrh4, msw1, and mrp49) and osmotic stress signaling (ssk2 and pbs2). Consistent with our HCS data and several previous publications linking the SUMO system to spindle function (Vizeacoumar et al., 2010; Pérez de Castro et al., 2011; Wan et al., 2012), SGA correlation analysis also highlighted several spindle and kinetochore genes (e.g., bub3, spc105-15, lte1, kar3, clk1, stu2-11, and stu2-12).

In sum, our genetic data implicate SUMO chains in several functions previously ascribed to the SUMO system, such as resolving DNA replication–associated repair structures, but also link them to some previously unsuspected biological roles, such as osmoregulation and higher order chromatin structure.

Derepression of stress- and nutrient-regulated gene transcription and aberrant transcription of cryptic intergenic regions in smt3allR strains

High-resolution whole genome nucleotide tiling arrays (see Materials and methods for details) were next used to characterize the transcription profile of cells defective for SUMO chain synthesis (as in Tsui et al., 2012). 36 genes were repressed and 225 mRNAs were expressed >1.5-fold higher in the smt3allR strain, as compared with parental cells (Table 3 and Table S3). The up-regulated mRNAs consisted primarily of genes implicated in stress responses, nutrient adaptation, cell wall components, mitochondrial proteins, sporulation, and mating; i.e., genes that are normally repressed under standard laboratory culture conditions, where cells are maintained in media with optimal carbon and nitrogen sources, and at optimal growth temperature. Increased transcription of this gene set likely accounts for many aspects of the pleiotropic smt3allR phenotype. For example, several genes implicated in mitochondrial function (e.g., STF1, ALD4, and CYC7) and cell wall integrity signaling (e.g., YGP1, KDX1, and PRM5) are up-regulated in this strain. These data suggest that SUMO chains are likely to be involved indirectly in each of these biological functions, via transcriptional control.

Table 3.

smt3allR tiling array gene expression analysis

| Category | Gene | log2 (fold change) | Gene | log2 (fold change) | Gene | log2 (fold change) | Gene | log2 (fold change) | Gene | log2 (fold change) | Gene | log2 (fold change) | Gene | log2 (fold change) |

| Nutrient/stress response | ||||||||||||||

| HSP12 | 2.912 | HSP104 | 1.229 | ECM4 | 0.954 | SPG4 | 0.765 | HMX1 | 0.606 | DDR2 | 2.872 | ALD3 | 1.200 | |

| MOH1 | 0.933 | TPS2 | 0.756 | YMR090W | 0.602 | HSP26 | 2.805 | SOL4 | 1.159 | HOR2 | 0.907 | DUR1,2 | 0.753 | |

| MSN4 | 0.602 | HUG1 | 2.404 | CRG1 | 1.139 | USV1 | 0.898 | HSP31 | 0.746 | PHO12 | –0.602 | TMA10 | 1.817 | |

| ADR1 | 1.133 | TMA17 | 0.896 | RNY1 | 0.741 | PHO11 | –0.604 | MSC1 | 1.803 | NTH1 | 1.131 | UBC5 | 0.893 | |

| YOR052C | 0.731 | SPL2 | –0.660 | TSL1 | 1.793 | ATG8 | 1.129 | HOR7 | 0.882 | YJL144W | 0.711 | ZRT1 | –0.760 | |

| GAD1 | 1.753 | CTT1 | 1.104 | PUT1 | 0.874 | AHA1 | 0.691 | RSN1 | –0.805 | HSP42 | 1.664 | FRE7 | 1.045 | |

| SOM1 | 0.860 | YNR014W | 0.677 | AAH1 | –0.805 | GLK1 | 1.635 | PRB1 | 1.037 | ATH1 | 0.852 | YNL134C | 0.676 | |

| PHM6 | –0.815 | TFS1 | 1.522 | NCE103 | 1.036 | SSA3 | 0.833 | GRX1 | 0.664 | HMS2 | –0.832 | PNC1 | 1.470 | |

| GTT1 | 1.022 | IGD1 | 0.826 | EDC2 | 0.637 | SSA4 | 1.465 | SSE2 | 1.009 | YJR096W | 0.811 | SPI1 | 0.631 | |

| GRE1 | 1.394 | GAC1 | 1.004 | TPS1 | 0.808 | RAD51 | 0.630 | GCY1 | 1.382 | PLM2 | 0.990 | GPD1 | 0.802 | |

| RCN2 | 0.630 | HSP78 | 1.338 | MCR1 | 0.980 | GRE3 | 0.800 | YAP6 | 0.628 | PGM2 | 1.317 | YDL124W | 0.968 | |

| CAR2 | 0.796 | PEP4 | 0.620 | XBP1 | 1.304 | PRX1 | 0.966 | PUT4 | 0.784 | YOR289W | 0.614 | YDR034W-B | 1.255 | |

| SDS24 | 0.962 | YKL151C | 0.771 | DAN4 | 0.609 | |||||||||

| Mating and sporulation | ||||||||||||||

| AGA2 | 2.532 | GPG1 | 1.320 | CWP1 | 1.064 | EMI2 | 0.694 | TPK1 | 0.606 | MFA1 | 1.555 | PRM1 | 1.227 | |

| BAR1 | 1.034 | GSM1 | 0.678 | PST2 | 0.604 | HBT1 | 1.552 | UBI4 | 1.223 | PRM6 | 0.931 | SPO12 | 0.651 | |

| TCB2 | –0.726 | FIG1 | 1.450 | FIG2 | 1.195 | RMD5 | 0.784 | FUS1 | 0.642 | PRM7 | –0.945 | |||

| GSC2 | 1.377 | AFR1 | 1.145 | YOR338W | 0.755 | AGA1 | 0.641 | RIM4 | 1.363 | PRM2 | 1.108 | FUS2 | 0.737 | |

| PTP2 | 0.628 | MFA2 | 1.345 | STE2 | 1.102 | KAR4 | 0.712 | SPS100 | 0.616 | |||||

| Carbohydrate metabolism | ||||||||||||||

| GPH1 | 2.447 | HXT6 | 1.136 | GND2 | 0.789 | PFK26 | 0.679 | HXK1 | 1.863 | HXT7 | 1.130 | YBR056W | 0.723 | |

| YLR345W | 0.673 | AMS1 | 1.699 | GSY2 | 1.056 | HXT5 | 0.720 | RKI1 | –0.616 | NQM1 | 1.423 | PIG1 | 0.914 | |

| CIT1 | 0.717 | HXT1 | –0.710 | GPM2 | 1.278 | GSY1 | 0.868 | UGP1 | 0.695 | GDB1 | 1.252 | GIP2 | 0.842 | |

| PYK2 | 0.695 | GLC3 | 1.192 | PCK1 | 0.789 | GUT2 | 0.689 | |||||||

| Cell wall | ||||||||||||||

| YGP1 | 2.467 | KDX1 | 1.176 | YPS6 | 1.017 | DSE1 | –0.650 | EGT2 | –0.718 | YPS5 | 1.204 | PRM5 | 1.103 | |

| PIR3 | 0.988 | SUN4 | –0.685 | PRY3 | –1.042 | |||||||||

| Autophagy | ||||||||||||||

| LAP4 | 1.229 | DCS1 | 0.981 | ATG34 | 0.878 | PAI3 | 0.738 | DCS2 | 1.025 | ALD2 | 0.892 | ATG33 | 0.743 | |

| ATG19 | 0.732 | |||||||||||||

| Mitochondrial | ||||||||||||||

| FMP16 | 1.902 | CYC7 | 1.036 | AIM17 | 0.984 | MRP8 | 0.702 | COX5B | 0.656 | CTP1 | –0.806 | STF1 | 1.622 | |

| INH1 | 0.993 | OM45 | 0.918 | UIP4 | 0.699 | MPM1 | 0.644 | ALD4 | 1.305 | FMP33 | 0.986 | YNL200C | 0.892 | |

| GOR1 | 0.664 | SDH2 | 0.633 | |||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||

| YPR160W-A | 2.593 | YDR042C | 1.159 | VMR1 | 0.901 | YMR181C | 0.747 | PIC2 | 0.641 | SFG1 | –0.605 | YGL101W | –0.823 | |

| YIL082W | 2.021 | YJL133C-A | 1.145 | LEE1 | 0.901 | YLR312C | 0.732 | YNL058C | 0.637 | LIA1 | –0.614 | YBR191W-A | –0.862 | |

| RTN2 | 1.860 | ROM1 | 1.143 | YOR343C | 0.867 | YBR139W | 0.726 | YPL088W | 0.632 | BSC1 | –0.615 | YMR317W | –0.907 | |

| YMR196W | 1.797 | BOP2 | 1.142 | PET10 | 0.858 | YOR192C-C | 0.709 | YHR052W-A | 0.624 | NIP7 | –0.629 | PLB2 | –0.923 | |

| NCA3 | 1.724 | CRG1 | 1.139 | YLR307C-A | 0.822 | YER053C-A | 0.692 | YPR145C-A | 0.623 | LYS1 | –0.633 | YMR046W-A | –1.003 | |

| RNR3 | 1.683 | RTS3 | 1.115 | YLR108C | 0.798 | COS12 | 0.690 | YCL076W | 0.622 | HTB2 | –0.654 | YOL014W | –1.206 | |

| PHM8 | 1.500 | GSP2 | 1.097 | PRY1 | 0.787 | BNA2 | 0.685 | PEX27 | 0.617 | YBL029W | –0.688 | YFR052C-A | 1.498 | |

| YKR011C | 1.053 | YDL247W-A | 0.783 | GAP1 | 0.684 | YLR042C | 0.617 | YPR002C-A | –0.708 | YNR034W-A | 1.365 | PBI2 | 0.993 | |

| YBR201C-A | 0.780 | YOR114W | 0.673 | VPS73 | 0.614 | ADE17 | –0.712 | RTC3 | 1.332 | SRL3 | 0.987 | CUR1 | 0.769 | |

| YNL115C | 0.670 | REC104 | 0.611 | HTA2 | –0.719 | YHR138C | 1.263 | ECL1 | 0.986 | YCL021W-A | 0.767 | GGA1 | 0.663 | |

| YHR007C-A | 0.608 | YNL217W | –0.729 | YLR149C | 1.179 | YCL042W | 0.954 | YDR379C-A | 0.758 | HER1 | 0.657 | RGC1 | 0.603 | |

| ARG8 | –0.764 | YBR085C-A | 1.178 | BTN2 | 0.926 | YCL049C | 0.758 | YBR053C | 0.652 | YHR177W | 0.602 | YDL038C | –0.799 |

High-resolution gene expression analysis of the smt3allR mutant revealed that 261 genes were over- or underexpressed as compared to parental cells.

We also observed a notable increase in transcription from silenced mating type and sporulation genes (e.g., MFA1, MFA2, RIM4, and PRM1), as well as several intergenic regions (Fig. S5 A and Table S3); e.g., 47 cryptic unstable transcripts (CUTs) were expressed >1.5-fold higher in the smt3allR strain than in parental cells. Together, these data indicate that disruption of SUMO chain synthesis has a wide-ranging negative effect on the maintenance of transcriptional repression. (It should also be noted that, although overall changes in the expression of individual transcripts are not extremely large in these mutants, this number reflects a population average. Because the phenotypes of individual smt3allR cells are pleiotropic, we suspect that these averages reflect much larger changes in a smaller subpopulation of cells.)

SUMO chains are required to establish a basal transcription “setpoint” for stress-regulated genes

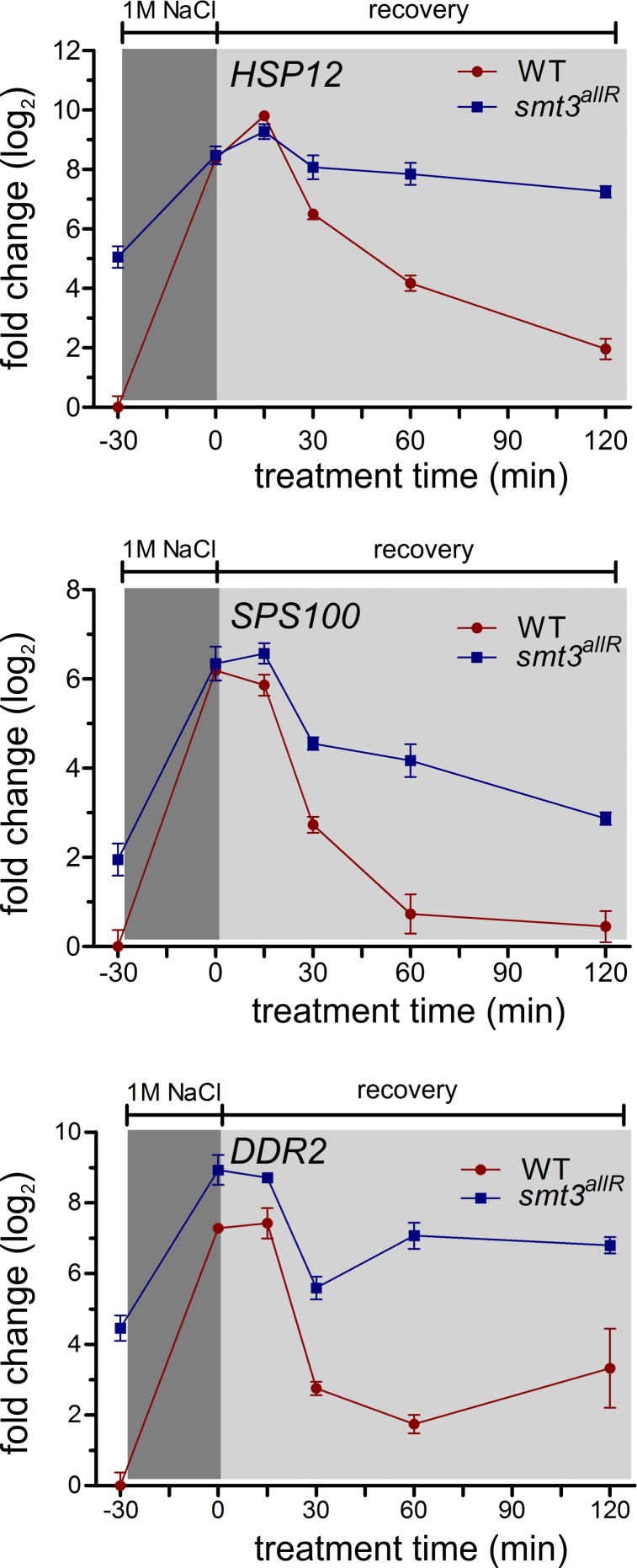

The transcription of stress-response genes is rapidly increased in response to changes in the extracellular environment (Gasch et al., 2000). To explore the role of SUMO chains in the transcriptional stress response, we subjected parental and smt3allR cells to hyperosmotic culture conditions (1 M NaCl for 30 min), followed by a 120-min recovery in isosmotic media. Using real-time qRT-PCR, expression levels of four different mRNAs that are overexpressed in smt3allR cells, and which are up-regulated in response to osmotic shock (HSP12, SPS100, GRE1, and HUG1), were monitored. As expected, in parental cells all four of the genes in the test set displayed a rapid increase in mRNA levels in response to hyperosmotic shock (Fig. 5 and Fig. S5 B). After a return to isosmotic media, a gradual decrease in mRNA abundance was observed, returning to pre-stress levels within 60–120 min (Fig. 5 and Fig. S5 B). Consistent with our tiling array data, this gene set was already expressed at higher levels in untreated smt3allR strains (Fig. 5 and Fig. S5 B). In response to osmotic shock, the four gene set was up-regulated to approximately the same expression levels (or slightly higher in some cases) as the parental strain, and removal of the stress resulted in a similar gradual decrease in mRNA abundance to near basal smt3allR transcript levels (Fig. 5 and Fig. S5 B). Identical results were observed in cells expressing the 3KR SUMO protein (Fig. S4 C). A deficiency in SUMO chain function does not therefore appear to significantly affect the activation kinetics or maximal mRNA expression levels in response to stress, but instead influences the basal transcription setpoint of this highly regulated group of genes.

Figure 5.

SUMO chains are required to establish a basal transcription setpoint for stress-regulated genes. Parental and smt3allR strains were grown in YPD and treated with 1 M NaCl for 30 min, then allowed to recover in YPD medium. Aliquots were collected at the indicated time points for RNA preparation. HSP12, SPS100, and DDR2 mRNA were monitored by qRT-PCR and values were normalized to ACT1 levels. Error bars indicate standard deviation from three or more biological replicates

SUMO chain disruption affects multiple aspects of higher-order chromatin organization

Aberrant mitotic chromosome condensation and segregation, transcriptional derepression of stress- and nutrient-regulated genes, and aberrant transcription from intergenic regions suggested that smt3allR strains could have a chromatin condensation defect. To this end, we subjected smt3allR and parental cells to several different assays of higher-order chromatin structure.

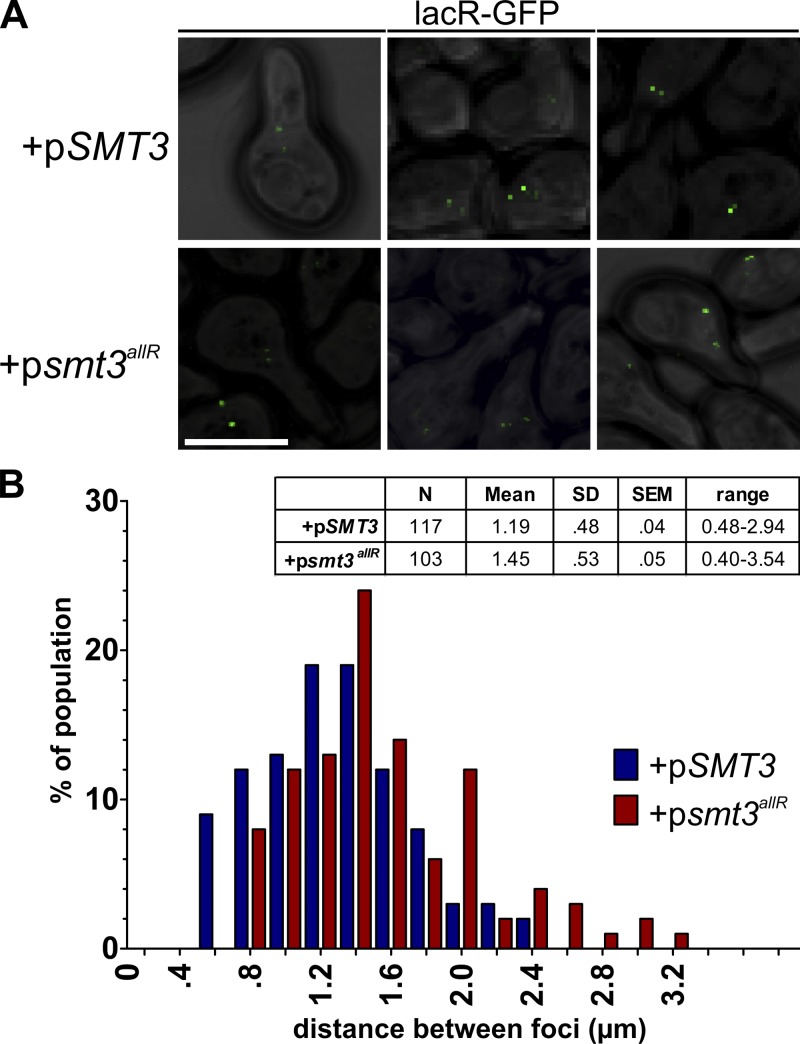

The lacO/lacR chromosome marker system.

To begin to assess how a lack of SUMO chains impacts chromatin structure, we used a yeast strain bearing two lac operon repeat insertions on chromosome IV, separated by ∼450 kb (strain AVY89; Vas et al., 2007). When the lacR-GFP protein is bound to its cognate operon, confocal microscopy can be used to measure the distance between the two GFP foci (Vas et al., 2007). Plasmids encoding the gal-inducible WT or allR SUMO proteins were transformed into this strain, cells were exposed to galactose to induce SUMO protein expression for 16 h, and cells were treated with α factor to synchronize them in G1. The distance between GFP signals was then quantified, as in Vas et al. (2007). In cells expressing the WT SUMO protein, the two GFP foci were 1.19 ± 0.04 µm apart on average, the same as that observed in the untransformed parental strain (Fig. 6, A and B) and similar to measurements previously reported in other laboratory strains (Vas et al., 2007). Notably, in the strain expressing the SUMO allR protein, the mean distance between the GFP-marked chromosome regions was significantly increased (1.45 ± 0.05; P < 0.01; Fig. 6, A and B). Inhibition of SUMO chain formation thus negatively affects chromosome IV compaction and/or organization.

Figure 6.

Higher-order chromatin organization is disrupted in cells expressing the SUMO allR protein. (A) WT SUMO or smt3allR protein expression was induced in AVY89 (lacO/lacR-GFP) cells for 16 h, and the distance between GFP foci on chromosome IV was measured as in Vas et al. (2007). Bar, 5 µm. (B) Data (from >100 cells) are presented in tabular form (values are expressed in micrometers) and as a bar graph with binned distance values, as indicated. Data shown are from a single representative experiment, conducted twice.

Telomere clusters.

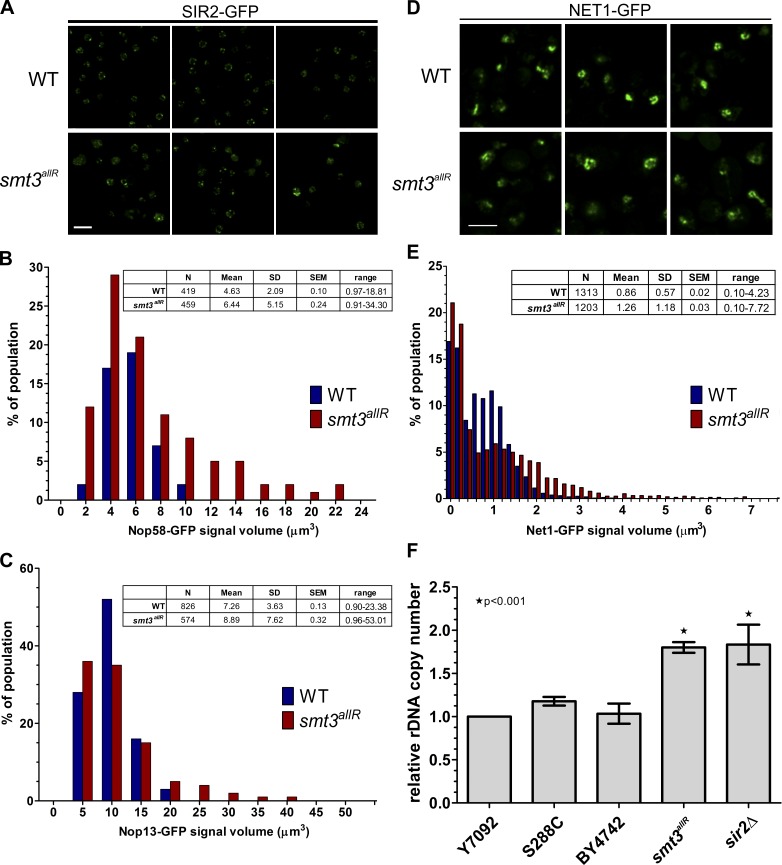

The SUMO system was also previously linked to telomere silencing and localization (Chen et al., 2007; Mekhail et al., 2008; Ferreira et al., 2011). During interphase, budding yeast telomeres are clustered into 3–8 foci located near the inner nuclear membrane (INM; Mekhail et al., 2008). To determine if SUMO chains are important for proper telomere organization, we examined the localization of the telomere regulatory protein SIR2 in parental and smt3allR strains. As expected, in parental strains, SIR2-GFP was found in a small number of foci near the INM. However, smt3allR cells displayed an increased number of (generally smaller) SIR2-GFP foci, and many cells possessed an additional diffuse nuclear SIR2 signal (Fig. 7 A), which indicates widespread SIR2 mislocalization.

Figure 7.

Nucleolar and telomere organization are disrupted in cells expressing the SUMO allR protein. (A) SIR2-GFP was imaged in log-phase cells in parental and smt3allR backgrounds. (B–E) GFP-tagged NOP58, NOP13, and NET1 strains were arrested in S phase by HU treatment and released into nocodazole-containing medium. Nucleolar/rDNA area was analyzed by quantifying NOP58 (n > 400), NOP13 (n > 500), and NET1 (n > 1,200) GFP signals. Volocity software was used to automate measurements of GFP signal volume across 9 z stacks. (D) Confocal micrographs of NET1-GFP in parental and smt3allR cells. Data shown are from a single representative experiment, conducted twice. Bars, 5 µm. (F) rDNA copy number (relative to the WT strain Y7092) was measured by qPCR using the ΔΔCt method. Experiments were performed in triplicate (where each reaction was also performed in triplicate); error bars indicate standard deviation.

Nucleolar chromatin organization.

The ribosomal DNA (rDNA) genes occur in a tandem array of ∼150 copies in budding yeast laboratory strains, comprising ∼1 Mb of chromosome XII (Johzuka and Horiuchi, 2009), and are organized into a compact structure localized near the INM, the nucleolus (Chan et al., 2011). Transcription of rDNA is tightly controlled, and specialized silencing mechanisms are required to prevent homologous recombination between rDNA repeats and to maintain rDNA copy number (Conconi et al., 1989; Dammann et al., 1995). The SUMO system plays an important (but poorly understood) role in these processes (Takahashi et al., 2008; unpublished data). To better understand the role of SUMO chains in rDNA organization and maintenance, several different nucleolar markers were expressed and analyzed in parental and smt3allR cells. Notably, the NOP2-GFP protein exhibited a much more diffuse pattern in cycling smt3allR cells (Fig. S5 C), implicating SUMO chain function in the organization of nucleolar DNA. To confirm and extend this result, NOP58-GFP–, NOP13-GFP–, and NET1-GFP–expressing cells were arrested in S phase by HU treatment (0.2 M for 90 min) and released into nocodazole-containing medium (15 µg/ml for 90 min) to synchronize them at the G2/M boundary, when budding yeast rDNA is partially compacted in preparation for mitosis (Guacci et al., 1994; D’Ambrosio et al., 2008). The signal volume of NOP58-GFP and NOP13-GFP was much more variable in smt3allR cells as compared with parental strains (Fig. 7, B and C). Similarly, although the total NET1-GFP fluorescence signal intensity was equal in both strains, the signal volume was much more variable, and larger on average, in smt3allR cells (P < 0.0001; Fig. 7, D and E). Together, these data indicate that nucleolar DNA organization is also altered in a budding yeast mutant unable to synthesize SUMO chains.

Previous work has demonstrated that a loss of rDNA repeat organization or localization can lead to changes in rDNA copy number (Takahashi et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2011). Using quantitative PCR (qPCR), we found that the rDNA repeat number is significantly increased in smt3allR cells, as compared with their parental counterparts (Fig. 7 F). Similar to chromosome IV and telomeres, rDNA compaction and/or organization (as judged by several different GFP markers and quantitation of rDNA repeat number) is thus also compromised when SUMO chain function is disrupted.

Discussion

Many transcription factors, coregulators, and chromatin remodeling proteins are SUMO targets (for review see Gill, 2005), and sumoylation of chromatin remodelers in yeast and mammalian cells has been suggested to be required for the formation of a local heterochromatin-like state on some promoters (Uchimura et al., 2006). A recent study indicated that Ubc9 inactivation in S. cerevisiae leads to increased transcription at the inducible ARG1 gene and impaired the ability of these cells to inactivate ARG1 transcription after removal of the activation signal (Rosonina et al., 2010). SUMO has also been reported to be enriched in heterochromatic DNA regions (Uchimura et al., 2006), and sumoylation of the ubiquitous transcription factor Sp3 has been linked to local heterochromatinization (Stielow et al., 2008b), whereas expression of an unsumoylatable Sp3 protein leads to derepression of several tissue-specific genes in mammalian cells (Stielow et al., 2010). Here, we find that disruption of SUMO chains in yeast negatively affects higher-order chromatin organization and the maintenance of transcriptional repression. We propose that a general, widespread defect in chromatin packaging (as reflected by increased distances between two chromosomal markers, disorganized telomere clustering, and altered nucleolar rDNA organization) leads to transcriptional derepression throughout the genome. In this way, SUMO chains appear to play an important role in establishing a basal transcription setpoint. Our data also indicate that SUMO chains are not required for stress-regulated transcriptional activation. However, the precise role of SUMO chains in transcriptional inactivation is not yet clear: although SUMO chains are clearly required to maintain transcriptional repression in yeast, they do not seem to be required for at least a partial inactivation of transcription after stress (Fig. 5). Additional exploration of the role of SUMO chains in transcriptional inactivation may shed further light on these findings.

The SUMO system has also been implicated in DNA replication and DNA damage repair (Makhnevych et al., 2009; Cremona et al., 2012). Our data specifically implicate SUMO chains in DNA replication–associated DNA damage. How might this damage occur in smt3allR cells? DNA lesions can block the progress of DNA replication forks. Although replication can restart via repriming downstream of the damaged area (Heller and Marians, 2006), the repriming process generates a single-stranded gap near the lesion (Lehmann and Fuchs, 2006). To fill these gaps, the template switch (TS) pathway may be used. TS utilizes undamaged DNA on the sister chromosome via a mechanism that shares similarities with homologous recombination (Goldfless et al., 2006; Branzei and Foiani, 2007). The TS process gives rise to X-shaped DNA intermediates, with biochemical properties similar to pseudodouble Holliday junctions (for review see Klein, 2006). A failure to resolve these structures can lead to DNA damage and chromosomal rearrangements. The RecQ helicase Sgs1 (the budding yeast orthologue of the human BLM protein) is required for resolution of these structures (Liberi et al., 2005; Wu and Hickson, 2006), and the ability of Sgs1 to promote their dissolution is regulated by the SUMO pathway (Branzei et al., 2006). Recent work has also demonstrated that the Smc5-6 complex, Esc2, and the Mms4-Mus81 complex (all of which were detected in our SGA and HCS analyses) play important roles in resolving these recombination intermediates on damaged DNA templates (Branzei et al., 2006; Chavez et al., 2010). Mutant smc5-6 and smc6-9 cells are sensitive to MMS treatment, and undergo aberrant mitosis in which chromosome segregation of repetitive regions is impaired (Torres-Rosell et al., 2005). Consistent with these data, the SUMO mutant strain smt3-331 was isolated in a high-content screen for cells unable to properly segregate GFP-labeled chromosomes (Biggins et al., 2001). Our smt3allR mutant shares several similarities with this group of strains, implicating SUMO chains in the same processes.

It is important to note that the SUMO proteins may be regulated by posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitylation (Matic et al., 2008; Mazur and van den Burg, 2012). However, acetylation of lysine residues in the human SUMO proteins inhibits (or has no effect on) SUMO–SIM interactions, and K-to-R mutations at acetylation sites do not affect their activity in transcriptional repression and protein binding assays (Ullmann et al., 2012). As reported here, the 3KR yeast SUMO mutant has the same effect as the allR SUMO protein in assays of division time, ploidy, and mRNA expression levels. K-to-R mutations are thus not likely to significantly disrupt SUMO function, other than to abrogate chain synthesis. Nevertheless, because we do not completely understand how the yeast SUMO protein may be posttranslationally modified, we cannot rule out this possibility.

Finally, our data also have clear implications for human disease. For example, a SUMO chain deficit could render cells more susceptible to chemotherapeutic agents because of a heavier DNA damage load and increased chromosome missegregation. Indeed, although the molecular details of this phenomenon are not yet understood, a recent study linked SUMO E1 mutations to improved outcome in some (Myc mutation–associated) breast cancers (Kessler et al., 2012). Combined with our observations, these data suggest that targeting of the SUMO system (and in particular SUMO chain synthesis) could have therapeutic value.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study were derivatives of the BY4741/2 haploid cells, unless otherwise specified, and are listed in Table S4. All yeast genetic manipulations were performed according to established procedures. Unless otherwise noted, yeast strains were grown at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase in YPD or selective minimal (SM) media supplemented with appropriate nutrients and 2% glucose. Transformations were performed as described previously (Delorme, 1989). The AVY89 strain was kindly provided by D.J. Clarke (University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN).

Construction of smt3allR strains

Multistep PCR was used to generate a product containing the NatMX cassette from p4339, 207 bp of the Smt3 5′ UTR from genomic DNA, the smt3allR coding DNA sequence from Bylebyl et al. (2003), and 273 bp of the Smt3 3′ UTR from genomic DNA. The resulting product was used to transform yeast strains as in Gietz and Woods (2002). See Table S5 for primers.

Whole cell lysate preparation, affinity purification, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were prepared by alkaline lysis and trichloroacetic acid protein precipitation of cell pellets derived from 10-ml cultures. Protein pellets were resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, sonicated for 10 s, and incubated at 90°C for 5 min before SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Pall) and probed with HA.11 (Covance), anti-Smt3 (Covance), or anti-actin (EMD Millipore). Proteins were visualized with secondary HRP-conjugated anti–mouse or anti–rabbit antibodies (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and ECL (Immuno-Star HRP; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Recombinant protein purification and quantification

pGEX-6P-1-SMT3 or pGEX-6P-1-smt3allR, encoding an N-terminal GST moiety fused to the SMT3 or smt3allR coding regions (1–294), was constructed using standard cloning techniques, and verified by DNA sequencing. The pGEX-6P-1-SUMO proteins were expressed in BL21 Escherichia coli induced with 2 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside at 16°C for 16 h. Proteins were purified using MagneGST glutathione particles (Promega), according to manufacturer’s instructions. WT and allR SUMO proteins were cleaved free of the GST moiety using a 4% PreScission Protease solution (GE Healthcare) at 4°C for 16 h. Proteins were assessed for purity using SDS-PAGE and quantified with a Bradford assay. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels were digitized using a scanner (Epson), and intensity measurements on individual bands were made on the digitized images using Photoshop CS4 (Adobe) software.

In vitro sumoylation

Assays were performed with 150 ng of E1 (AOS1/UBA2), 1 µg of E2 (UBC9), 2 µl of 10× sumoylation reaction buffer (200 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 50 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM ATP), 1 µg of SUMO, and 250 ng of biotinylated substrate (all proteins from Boston Biochem). The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 2 h, then quenched with SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using streptavidin-conjugated HRP (Bio-Rad Laboratories). After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane (Pall), proteins were visualized using a 2% solution of Ponceau S in 1% acetic acid.

Electron microscopy

Samples were prepared as in Wright (2000), and visualized on a transmission electron microscope (H-7000; Hitachi). In brief, cells were fixed with 4% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 5 min. Cells were washed and secondary fixed with 2% potassium permanganate at room temperature for 5 min. Cells were then washed and overlayed with 1% uranyl acetate for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then dehydrated by incubating in increasing amounts of ethanol over an 8-h period. Next, cells were infiltrated in Spurr’s resin and samples were polymerized in embedding mold at 60°C for 48 h. 90-nm-thin sections were mounted on 200 mesh copper grids and stained with lead citrate for 5 min before observation with the transmission electron microscope (H7000) at 75 kV. Images were captured in TIF format.

Oxygen consumption rate measurements

Cultures were grown overnight (O/N) in YPD media and diluted in the morning to OD600 0.1 in fresh YPD media. 1 ml of OD600 0.3 culture was collected, washed twice with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, and resuspended to OD600 0.3. Resuspended cells were used to seed XF96 plates (Seahorse Biosciences). Plates were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 2 min, then allowed to rest for 30 min at 30°C. The Seahorse sensor cartridge was rehydrated O/N as per the manufacturer’s instructions. XF96 culture plates and sensor cartridge were mated and placed in a Seahorse instrument, set to maintain temperature at 30°C. An initial wait time of 20 min was added to allow equilibration of the culture to instrument conditions. After 1 min of mixing, a 1-min wait time was also included to allow for cell settling, before measuring for 2 min. Three measurements were taken for the basal reading, before the addition of azide to a final concentration of 0.05% in media. Three additional readings were then taken. The mean of the three readings across the 2-min span was calculated for each well. Six wells were used for each strain.

High-content microscopic screen

An array consisting of 384 strains (Table S3) from the yeast GFP collection (Huh et al., 2003) expressing proteins previously demonstrated to display altered localization or intensity in response to replication stress (Tkach et al., 2012) was constructed and crossed with the smt3allR mutant (smt3allR::NatMX NUP49-mCherry::URA3 or pro-smt3allR::NatMX NUP49-mCherry::URA3) using SGA (Tong and Boone, 2007) to yield 384 GFP-ORF strains bearing the smt3allR allele. GFP protein localization and relative steady-state abundance for each strain in the WT and smt3allR mutants were determined essentially as described in Tkach et al. (2012). In brief, cultures were grown to mid-log phase in low-fluorescence medium and transferred to 384-well slides at a final density of 0.045 OD600/ml. Four images per well in the green and red channels (800 ms exposure) were simultaneously acquired, imaged using a high-throughput confocal microscope system (EVOTEC Opera; PerkinElmer) with quad-band dichroic filter (405/488/561/653). The images were blinded and scored manually for localization and relative abundance changes versus the WT GFP-ORF (Huh et al., 2003). A brief description was recorded for each protein undergoing a change in the smt3allR or pro-smt3allR strains.

Confocal microscopy

Mid-log phase cells were collected from 1-ml cultures, washed in brief in H2O containing 2% glucose, and mounted on a glass slide. Cells were imaged at room temperature using a 100×/1.40 NA Plan-Apochromat lens on an inverted microscope (IX80; Olympus) fitted with a spinning disk confocal scanner unit (Yokogawa CSU10; Quorum Technologies, Inc.) and a 512 × 512 EM charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Hamamatsu Photonics). Diode lasers at 561 nm (RFP), 491 nm (GFP), and 405 nm (DAPI) were used for excitation combined with the following filter sets: 500/20 nm, 430/10 nm, and 555/28 nm. The system was controlled with Volocity 5.5 software (PerkinElmer). The CCD camera was operated at maximum resolution. Exposure times, gain, and sensitivity varied by protein; however, the same settings were used in WT and smt3allR strains. Settings were maintained for all subsequent images of the same strain. Cropping and gamma adjustments of images were performed using Volocity (image export) and Photoshop CS4.

For experiments requiring fluorescent labeling of vacuoles, FM4-64 was added to culture media to a concentration of 20 µM and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Cultures were washed twice with media, then resuspended in fresh media and allowed to grow for another hour before imaging. To achieve hypertonic shock, cells were treated with 0.4 M NaCl for 10 min before imaging. To achieve hypotonic shock, cells were treated with 20 mM MES for 10 min before imaging. Nine z stacks 0.4 µm apart were acquired. Exposure time, sensitivity, gain, laser power, and binning were kept constant between all strains.

For fluorescent mitochondrial labeling, the plasmid pVT100U-mtGFP (Westermann and Neupert, 2000) was transformed into strains using electroporation. Strains were grown O/N, diluted to an OD600 of 0.2, and allowed to grow for 3 h. 0.1 µM MitoTracker red CMXRos (Invitrogen) and 7.5 µg/ml DAPI (Biotium, Inc.) were added to the culture media and incubated at 30°C for 2 h. Cells were then washed once with 1 M sorbitol, resuspended in 0.5 ml of 1 M sorbitol with 30 µl of 37% formaldehyde, and left on the benchtop for 5 min with occasional vortexing. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and stored at 4°C until they were imaged. Nine z stacks 0.4 µm apart were acquired. Exposure time, sensitivity, gain, laser power, and binning were kept constant between all strains.

For nucleolar/rDNA condensation experiments, cells were grown O/N in CSM His‒ media with 2% glucose at 26°C. The next morning, 1 ml of OD600 0.3 cells were collected and resuspended in YPD containing 0.2 M HU for 90 min at 30°C. Cells were washed three times with water and resuspended in YPD containing 15 µg/µl nocodazole for 90 min at 30°C. Cells were then washed once with 1 M sorbitol and resuspended in 0.5 mL of 1 M sorbitol. Formaldehyde was added to 2% (final) and cells were incubated at room temperature for 5 min, with gentle vortexing every 30 s. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, and stored at 4°C until they were imaged. Nine z stacks 0.4 µm apart were acquired. Exposure time, sensitivity, gain, laser power, and binning were kept constant between all strains. Volocity software was used to automatically identify cells using brightfield at 8% threshold cutoff (also a cutoff of >2 µm3). Within objects identified as a cell, the fluorescence intensity in the GFP channel was measured within 2 SD of the mean, and the volume occupied by this fluorescence signal was computed. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare means of fluorescence volumes. To represent data graphically, volumes were binned and shown as a percentage of the population.

Flow cytometry analysis

Approximately 107 mid-log phase cells were resuspended in 70% EtOH for fixation. Flow cytometry analysis was performed with a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; BD) and CellQuest Pro software (BD). DNA was stained using the fluorescent dye Sytox green (Invitrogen) at a 1:5,000 dilution. Data were analyzed using a free version of Cyflogic (CyFlo Ltd.).

Cellular glycerol levels

To determine total glycerol content, a 1-ml aliquot of YPD grown cells (OD600 = 0.6) was collected by centrifugation, washed twice with water, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of 100 mM Tris, pH 7.4. Samples were boiled for 10 min and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 15 min (4°C), and 10 µl of the supernatants were assayed for glycerol content. Glycerol concentration was determined colorimetrically with a commercial kit (EnzyChrom Glycerol Assay kit, EGLY-200; BioAssay Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

SGA analysis/SGA correlation analysis

SGA and correlation analyses were conducted as in Baryshnikova et al. (2010) and Costanzo et al. (2010). In brief, smt3allR query strains were crossed with 3,885 nonessential deletion mutants to generate double mutants via several selection steps. The fitness of double mutants was evaluated by measuring colony size in an automated fashion (see Baryshnikova et al., 2010 for details). Genetic interaction profile similarities were measured for all query and array gene pairs by computing Pearson correlation coefficients (PCC) for the complete genetic interaction matrix in Costanzo et al. (2010) and the SGA with the smt3allR. SGA was conducted using two different clones of the smt3allR mutant (one expressing the pro-SUMO protein and one expressing the mature SUMO polypeptide) in the Y7092 SGA parental strain. Genes identified to be synthetic sick in both screens were considered to be true positives.

Transcriptome analysis

WT and smt3allR strains were grown to mid-log phase in YPD media. Samples were centrifuged and snap-frozen. Total RNA and single-stranded cDNA were prepared according to Juneau et al. (2007), except that actinomycin D was added to a final concentration of 6 µg/ml during cDNA synthesis to prevent antisense artifacts (Perocchi et al., 2007). In brief, RNA was extracted with hot phenol from mid-log phase cultures, and total RNA was treated for 10 min at 37°C with RNase-free DNaseI, repurified using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) and eluted with 1× Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0. Single-stranded cDNA was synthesized in 200-µl reactions containing 0.25 µg/µl total RNA, 12.5 ng/µl random primers, 12.5 ng/µl oligo(dT)12-18 primer, 15 units/µl SuperScript II (Invitrogen), 1× first strand buffer, 10 mM DTT, 6 ng/µl actinomycin D, and 10 mM dNTP. After cDNA synthesis, RNA was degraded with 1/3 volume of 1 M NaOH incubated for 30 min, and an addition of 1/3 volume of 1 M HCl was used to neutralize the solution before cleanup with the MinElute Reaction Cleanup kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was fragmented with 2.1 units/µl DNaseI and labeled in 50 µl reactions containing 0.3 mM GeneChip DNA labeling reagent, 1× terminal transfer reaction buffer, and 2 µl of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Promega) for 60 min at 37°C. Labeled cDNA was hybridized to arrays for 16 h at 45°C. Raw data from Affymetrix GCOS software (.CEL format) was analyzed with Affymetrix Tiling Analysis software (TAS; http://www.affymetrix.com/partners_programs/programs/developer/TilingArrayTools/index.affx). Expression levels were mapped to the chromosomal map from the Saccharomyces Genome Database and are available for download as supplemental .bar files.

qRT-PCR

Strains were grown O/N, diluted to OD600 0.2, and grown to 0.6. Cultures were shocked with 1 M NaCl for 30 min, then allowed to recover in fresh YPD media for 120 min. 5-ml culture aliquots were collected at the indicated time points and snap-frozen. The MasterPure Yeast RNA Purification kit (Epicenter) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions to prepare purified RNA. RNA quality (RIN) was analyzed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA quantity was estimated with a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR primers were designed using the cDNA for each desired target with qPCR settings in Primer3Plus (see Table S5; Untergasser et al., 2007). 40 ng of template RNA and 50 nM of each primer were used with the Power SYBR green RNA-to-CT 1-Step kit (Applied Biosystems) in 20-µl reactions, as per the manufacturer’s instructions, on a qPCR system (Mx3000P; Stratagene). Act1 was used as a control for ΔΔCt-based relative quantification (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

qPCR

Strains were grown O/N in YPD (200 µg/ml +cloNAT or 100 µg/ml +G418 for mutants), diluted in the morning to OD600 of 0.2. Cultures were grown to OD600 0.8, and 10-ml aliquots were snap-frozen. A MasterPure Yeast DNA Purification kit (Epicentre) was used to isolate genomic DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were incubated with DNase-free RNase for 2 h in TE before storing at −20°C. DNA was quantified with a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 1000). A Power Sybr green PCR kit was used in 20-µl reactions containing 1 ng of DNA and 50 nM of each primer, as per the manufacturer’s instructions, on a qPCR system (Mx3000P). Primers were as follows: rDNA-F, 5′-TACTGCGAAAGCATTTGCCAAGGACG-3′; rDNA-R, 5′-TCCCCCCAGAACCCAAAGACTTTGAT-3′; act1-F, 5′-CTTTCAACGTTCCAGCCTTC-3′; and act1-R, 5′-CCAGCGTAAATTGGAACGAC-3′.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows data indicating that the smt3allR strains exhibit markedly increased chromosome segregation defects, and additional spot assays. Fig. S2 contains representative images from the HCS showing mislocalized spindle proteins, and highlights characteristics of an environmental stress response in SUMO mutant strains. Fig. S3 contains additional EM images, as well as measurements on internal glycerol content and FM4-64 vacuole-stained images. Fig. S4 contains doubling time, FACS, and gene expression data for strains overexpressing an smt33KR protein. Fig. S5 displays a summarized image of microarray data for the smt3allR strain, an expression profile for the Gre1 mRNA during stress response, and representative images from the HCS for NOP2-GFP. Table S1 contains localization and intensity data from the HCS, as well as GO analysis. Table S2 contains all SGA and correlation analysis data, as well as GO analysis. Table S3 contains expression data for all ORFs and known CUTs. Table S4 contains details on strains used in this study. Table S5 lists the sequences of all primers used in this study. Two .bar files, containing expression level changes mapped to chromosome location, are available for download. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201210019/DC1. Additional data are available in the JCB DataViewer at https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201210019.dv.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yan Chen and Dr. Paul Fraser at the University of Toronto EM facility and Connie Danielsen for expert technical assistance, as well as A.-C. Gingras and the Raught laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. We are also very grateful to D.J. Clarke for yeast strains.

T. Srikumar was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research student fellowship. Work in the G.W. Brown laboratory was supported by grant 020254 from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. C. Boone and B.J. Andrews were supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1R01HG005853-01) and by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-102629 and MOP-97939) and the Ontario Research Fund (GL2-01-22). B. Raught holds the Canada Research Chair in Proteomics and Molecular Medicine, and funding for work in the B. Raught laboratory was provided by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant MOP81268.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- CUT

- cryptic unstable transcript

- GO

- gene ontology

- HCS

- high content screen

- HU

- hydroxyurea

- INM

- inner nuclear membrane

- MMS

- methyl methanesulfonate

- O/N

- overnight

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- rDNA

- ribosomal DNA

- SGA

- synthetic genetic array

- SIM

- SUMO-interacting motif

- STUbL

- SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-related modifier

- TS

- template switch

- WT

- wild type

References

- Abed M., Barry K.C., Kenyagin D., Koltun B., Phippen T.M., Delrow J.J., Parkhurst S.M., Orian A. 2011. Degringolade, a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase, inhibits Hairy/Groucho-mediated repression. EMBO J. 30:1289–1301. 10.1038/emboj.2011.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton T.M., Hickson I.D. 2010. Yeast as a model system to study RecQ helicase function. DNA Repair (Amst.). 9:303–314. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryshnikova A., Costanzo M., Kim Y., Ding H., Koh J., Toufighi K., Youn J.Y., Ou J., San Luis B.J., Bandyopadhyay S., et al. 2010. Quantitative analysis of fitness and genetic interactions in yeast on a genome scale. Nat. Methods. 7:1017–1024. 10.1038/nmeth.1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencsath K.P., Podgorski M.S., Pagala V.R., Slaughter C.A., Schulman B.A. 2002. Identification of a multifunctional binding site on Ubc9p required for Smt3p conjugation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47938–47945. 10.1074/jbc.M207442200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggins S., Bhalla N., Chang A., Smith D.L., Murray A.W. 2001. Genes involved in sister chromatid separation and segregation in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 159:453–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D., Foiani M. 2007. Template switching: from replication fork repair to genome rearrangements. Cell. 131:1228–1230. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D., Sollier J., Liberi G., Zhao X., Maeda D., Seki M., Enomoto T., Ohta K., Foiani M. 2006. Ubc9- and mms21-mediated sumoylation counteracts recombinogenic events at damaged replication forks. Cell. 127:509–522. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruderer R., Tatham M.H., Plechanovova A., Matic I., Garg A.K., Hay R.T. 2011. Purification and identification of endogenous polySUMO conjugates. EMBO Rep. 12:142–148. 10.1038/embor.2010.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylebyl G.R., Belichenko I., Johnson E.S. 2003. The SUMO isopeptidase Ulp2 prevents accumulation of SUMO chains in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 278:44113–44120. 10.1074/jbc.M308357200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro P.H., Tavares R.M., Bejarano E.R., Azevedo H. 2012. SUMO, a heavyweight player in plant abiotic stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69:3269–3283. 10.1007/s00018-012-1094-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.N., Poon B.P., Salvi J., Olsen J.B., Emili A., Mekhail K. 2011. Perinuclear cohibin complexes maintain replicative life span via roles at distinct silent chromatin domains. Dev. Cell. 20:867–879. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]