Abstract

Commercially pure titanium plates/coupons and pure titanium powders were soaked for 24 h in 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions, under identical conditions, over the temperature range of 37° to 90°C. Wettability of the surfaces of alkali-treated cpTi coupons were studied by using contact angle goniometry. cpTi coupons soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH solutions were found to have hydrophilic surfaces. Hydrous alkali titanate nanofibers and nanotubes were identified with SEM/EDXS and grazing incidence XRD. Surface areas of Ti powders increased >50–220 times, depending on the treatment, when soaked in the above solutions. A solution was developed to coat amorphous calcium phosphate, instead of hydroxyapatite, on Ti coupon surfaces. In vitro cell culture tests were performed with osteoblast-like cells on the alkali-treated samples.

Keywords: Titanium, amorphous, calcium phosphate, coating, wettability

1. Introduction

Commercially pure titanium (cpTi) and its alloys (e.g., Ti-35Nb-5Ta-7Zr, TNZT) are lightweight and biocompatible metals clinically used as orthopedic, maxillofacial, and dental implants under load-bearing conditions. They possess lower elastic modulus, superior biocompatibility and enhanced corrosion resistance when compared to more conventional stainless steels and cobalt-based alloys [1]. However, none of these metals directly bonds to living bone and physical surface modifications, including hydroxyapatite or Bioglass® coatings, aimed at providing those with the bone-bonding ability [2–4]. Plasma-sprayed or thermal-sprayed bioceramic coatings on titanium are susceptible to peel off even during surgical implantation [2, 5].

The direct chemical bond between the host tissues and an implant surface would occur as the surface is conditioned by the plasma and tissue fluids, leading to the production of a layer of macromolecules, proteins and water on the implant surface which shall determine the behavior of cells when they come in contact with the surface [6, 7]. Vroman [8] indicated that on a surface, upon its contact with blood plasma, at least five proteins in succession displace each other within one minute. Nygren [9] directly compared the hydrophobic (i.e., titanium sheets soaked in butanol and then ethanol) versus hydrophilic (i.e., titanium sheets heated at 700–800°C in air followed by storing in water) titanium surfaces in contact (for 5 s) with whole blood and reported that the hydrophilic surfaces exhibited a higher amount of protein adsorption. The submicron roughness, micro-topography, and wettability of titanium surfaces are all influential in improving the macromolecule or protein attachment rate, and therefore, determining the doom of cell attachment/proliferation processes and the overall bone-bonding ability of the material [10].

Sand blasting with acid etching has been the most widely used technique, in industrial setting, to impart surface roughness and micro-topography to titanium implants [11–15]. However, especially when the sand (or grit) blasting is performed by using bioinert ceramic particles, it is not impossible to find a small percentage of those particles embedded or mechanically locked to the surface, which may then create a concern for the overall uniformity and reproducibility of the implant surface. Such sand-blasted and acid etched titanium samples were also stored in sealed glass tubes in nitrogen-saturated isotonic NaCl solutions to render the otherwise hydrophobic surfaces of cpTi hydrophilic [15, 16]. Zhang et al. [16] reported that hydrophilicity and roughness of Ti surfaces both promoted the proliferation of osteoblast-like cells. On the other hand, Linares et al. [17] found that bone-to-implant contact was around 65%, affirming relatively good osseointegration, when hydrophilic sand blasted and acid etched Ti implants were used in a 6 months minipig study.

In contrast to physical sand blasting, chemical treatment in alkali solutions is a strong contender to impart submicron- or nano-roughness to Ti surfaces. T. Kokubo has extensively published on 5 M NaOH treatment of Ti at 60°C and a consecutive 600°C heating in air, followed by the biomimetic hydroxyapatite coating via SBF (synthetic body fluid) solutions [18–25]. Kim et al. [26] reported the use of 10 M NaOH and 10 M KOH solutions to treat Ti however only the data of samples soaked in 10 M NaOH solutions were published.

Tas et al. [27] were the first to develop a two-step process which consisted of first soaking the Ti coupons/sheets in a 5 M KOH solution at 60°C for 24 h and 600°C heating for 1 h in air, followed by coating these alkali-modified surfaces, now containing a submicron surface roughness and topography, with an apatitic calcium phosphate layer at room temperature by using a supersaturated calcification solution corresponding to 10×SBF. 5 M KOH treatment of Ti was then independently repeated by Ito et al. [28], Tanaka et al. [29], Lee et al. [30, 31], Giannoni et al. [32], and Cai et al. [33].

Masaki et al. [34, 35] were the first to extensively study the Ti-KOH-H2O system over the temperature range of 150 to 350°C, by using Ti powder as the starting material, and suggested a diagram for the formation of crystalline or cryptocrystalline products at the region of KOH concentrations from 1 to 90 M. A similar comprehensive study for the Ti-NaOH-H2O system is still lacking. Ban [36] was the first one which treated the sand-blasted Ti plates separately in 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH at 60°C for 20 h, but failed to compare the surface morphology of those with one another. Tanaka et al. [29] only compared the surface topography of Ti specimens after their immersion in 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions at 80°C for 1, 6, 12 and 20 h. However, wettability (by using contact angle goniometry) of NaOH- or KOH-treated titanium surfaces has never been reported.

Based on the above short summary of previous literature, the current study is designed to compare (1) the surface morphology (by using scanning electron microscopy), (2) wettability (by using contact angle goniometry), (3) BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) surface areas, (4) phase identification of surface coatings by x-ray diffraction, and (5) the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) secretion activity by osteoblast-like cells seeded on cpTi specimens soaked separately in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH aqueous solutions at 37°, 60° or 90°C for 24 h. In contrast to the previous studies alkali-treated cpTi samples of this study were not heat treated at 600°C [18–27].

To the best of our knowledge, the current study will be the first one to comparatively report the morphology, wettability, phase identification by x-ray diffraction and osteoblast response to the surfaces of titanium coupons soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH solutions.

2. Materials and methods

Starting materials

Titanium coupons (10 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm) were cut from a larger cpTi sheet (ASTM-B265). Coupons were washed in boiling deionized water for 15 minutes, rinsed with water and finally dried at RT (room temperature, 22±1°C) in clean watch glasses. Analytical grade NaOH (No: S318, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) and KOH (No: 484016, Sigma-Aldrich St. Louis, MO) were used throughout the study in preparing the 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions. Ti powder (No: 268496, -100 mesh, 99.7%, Sigma-Aldrich) was used to prepare the samples for BET surface area measurements. Analytical grade NaCl (No: S9888, Sigma-Aldrich), KCl (No: P3911, Sigma-Aldrich), MgCl2·6H2O (No: AC19753, Fisher), CaCl2·2H2O (No: C79, Fisher), NaHCO3 (No: S233, Fisher), and NaH2PO4·H2O (No: SX-0710, EMD-Merck) were used in preparing the amorphous calcium phosphate deposition solutions described below.

Alkaline treatment

Alkaline treatments of Ti coupons (and powders, mainly for BET measurements) were performed in brand-new 250 mL-capacity, screw capped HDPE (high density polyethylene, Nalgene®, Fisher Scientific) bottles. 5 M NaOH or KOH solutions were first prepared in glass beakers. After placing one Ti coupon (with a mean weight of 0.35 g each) into one HDPE bottle, 50 mL of 5 M NaOH (i.e., 10 g NaOH in 50 mL water) or 5 M KOH (i.e., 14.02 g KOH in 50 mL water) was added. The isothermal heatings at 37°, 60° or 90°C for 24 h were performed in a microprocessor-controlled oven. Samples were then washed with an ample amount of deionized water and dried at RT. For the preparation of BET powder samples, 0.35 g Ti powder was placed in 50 mL of 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH solution. At the end of alkaline treatments powders were filtered and then washed with water, followed by drying at RT.

Ti coupons were needed basically for the contact angle goniometry, grazing incidence x-ray diffraction (GIXRD) and in vitro cell culture studies. Ti specimens in powder form were for surface area measurements and electron microscopy studies.

Amorphous calcium phosphate deposition

Select Ti coupons were deposited at 37°C with a layer of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP). The preparation of solution used in ACP coating is described in Table 1. This solution was free of any pH buffering agent such as Tris or Hepes. The BM-7 solution of pH 7.5, recently formulated by Temizel et al. [37], resembles the inorganic, amino acid- and vitamin-free portion of DMEM (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium) solution commonly used for in vitro cell culture studies. DMEM solutions do have a Ca/P molar ratio of 1.99, while the same ratio for this solution is adjusted to 2.50.

Table 1.

Preparation of ACP coating solution

| Chemical | BM-7 [37] | Ion | mM |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 4.7865 | Na+ | 126.86 |

| KCl | 0.3975 | Cl− | 93.39 |

| MgCl2·6H2O | 0.1655 | K+ | 5.33 |

| CaCl2·2H2O | 0.3330 | Mg2+ | 0.81 |

| NaHCO3 | 3.7005 | Ca2+ | 2.27 |

| NaH2PO4·H2O | 0.1250 | HCO3− | 44.05 |

| H2PO4− | 0.91 | ||

| Ca/P molar ratio | 2.50 |

The values of 2nd column, next to the chemicals, are in grams per L of water.

One alkali-treated Ti coupon was placed vertically inside a 125 mL-capacity glass bottle together with 100 mL of BM-7 solution shown in Table 1 and the screw capped bottle was stored in a 37°C oven for 96 h. The solution was replenished at every 24 h. At the end of 96 h, the CaP-coated Ti coupon was washed with deionized water and dried at RT.

Scanning electron microscopy

Morphology of all samples was studied by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL JSM-840A, Tokyo, Japan). Energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) was used to check the presence of Na or K on the surfaces of NaOH- or KOH-treated specimens and also to perform semi-quantitative chemical analyses. SEM and EDXS samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of Au-Pd alloy prior to imaging.

BET surface area

BET (Brunauer-Emmett-Teller) surface area measurements were performed on both as received (or as is, ai) Ti powders and Ti powders soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH solutions for 24 h at 37°, 60°, and 90°C. Surface areas of powder samples were determined by using the standard BET method to the nitrogen adsorption isotherm obtained at −196°C (Quantachrome Nova 2000e, Boynton Beach, FL).

Contact angle goniometry

The wettability of cpTi, NaOH-treated Ti, KOH-treated Ti and ACP-coated Ti coupons were determined by using an OCA 15 Plus (DataPhysics Instruments, Filderstadt, Germany) contact angle goniometer via the static sessile drop method (3 μ-L drop volume) with deionized water at RT. The contact angle goniometer photographs, which served as the sole comparison tool for wettability differences in the specimens of this study, were originally captured as a 15 minute movie at the rate of 25 fps (frame-per-second).

Grazing-incidence x-ray diffraction

Grazing-incidence x-ray diffraction (GIXRD) data of the alkali soaked or CaP-coated Ti samples were collected using a Rigaku Ultima IV x-ray diffractometer with parallel optics at the University of Oklahoma (Norman). A five mm divergence height limiting slit was used, and the divergence, scattering, and receiving slits were open. The source to sample fixed angle was 0.5°. X-ray tube settings of 40 kV, 44 mA, and 1.76 kW were used for all measurements. The data was collected in 0.02° steps for 15 s per step.

In vitro cell culture

MC3T3.E1 mouse osteoblast-like cells (a kind gift from Dr. Brenda J. Smith of Oklahoma State University) were grown in T-175 cm2 culture flasks at 37°C and 5% CO2 in alpha-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. The culture medium was changed every other day until the cells reached a confluence of 90–95%, as determined visually with an inverted microscope. The cells were passaged using 0.05% trypsin/0.53 mM EDTA solution (Cellgro, Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were collected then counted and plated at a density of 30,000 cells/well in a 24-well dish. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was assayed after 72 hours. The ALP activity was determined by Abcam Alkaline Phosphatase Colorimetric Assay kit (ab83369, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) per manufacturer's instruction. Background was subtracted from all standards, samples, and background controls. The pNPP (p-nitrophenylphosphate) standard curve was plotted in GraphPad Prism 4 and sample concentrations were extrapolated. Extrapolated concentrations were then used to calculate ALP activity based on the equation ALP activity (U/ml) = A/V/T where A equals amount of pNPP generated by samples (in μ-mol), V is volume of sample added in the assay well (in mL), and T is reaction time (in minutes).

Cell attachment/proliferation on the alkali-treated or amorphous calcium phosphate-coated Ti coupons used in cell culture study was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Cells were first fixed by immersing them in a solution of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 for 4 days at 4°C, and then washed twice with phosphate buffer, followed by dehydrating through sequential washings (10 min each) in 25%, 50%, 70%, 85%, 95%, and 100% ethanol solutions. Samples were then CO2-critical point dried, prior to sputter coating with a thin layer of Au-Pd.

Ca leaching test

Experiments were conducted to test the possibility for Ca leaching from glassware. 100 mL solutions of 5 M NaOH were prepared in HDPE and glass beakers. Triplicate samples were extracted by pipette after 15 and 60 minutes. Samples were analysed for dissolved Ca by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAnalyst 800, Perkin Elmer, Sheldon, CT).

3. Results and discussion

Keeping the concentration of the NaOH and KOH solutions (at 5 M) and the time of treatment (at 24 h) constant throughout this study enabled us to directly observe the influence of treatment temperature on the surface morphology/topography of Ti samples. Previous studies [28–36] were not designed to study the effect of temperature alone in comparing NaOH versus KOH treatments.

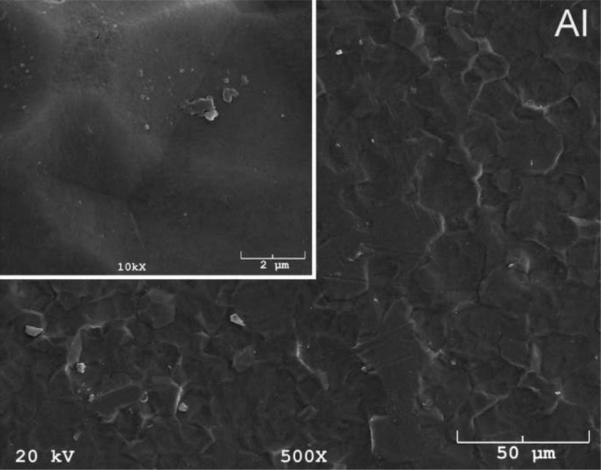

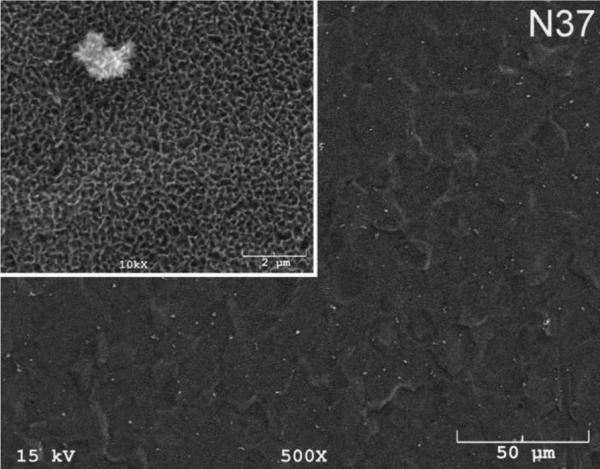

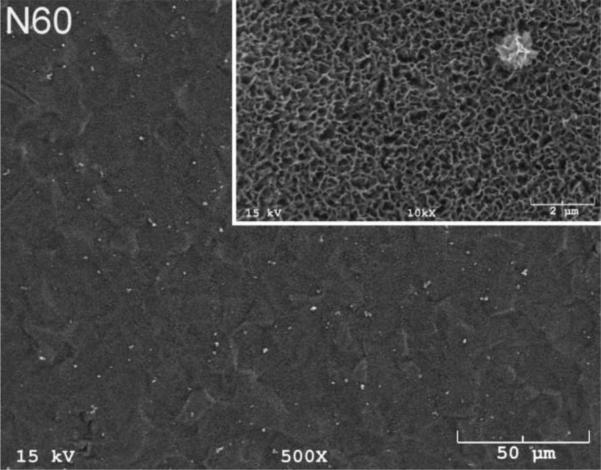

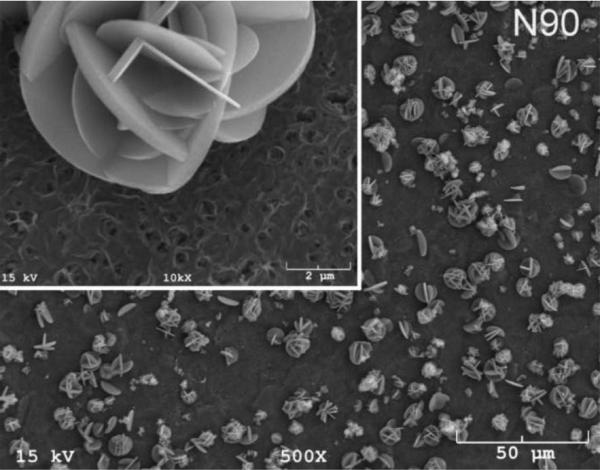

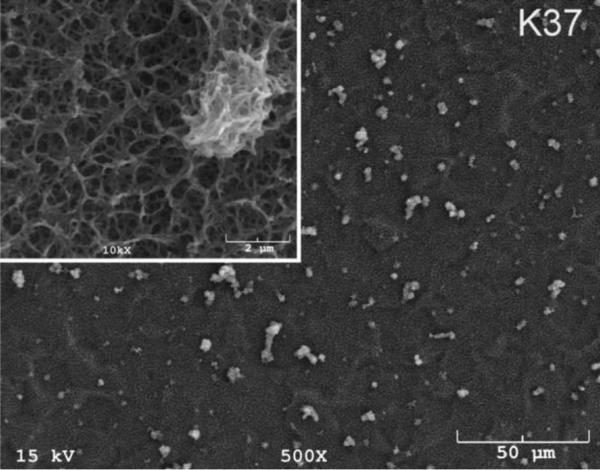

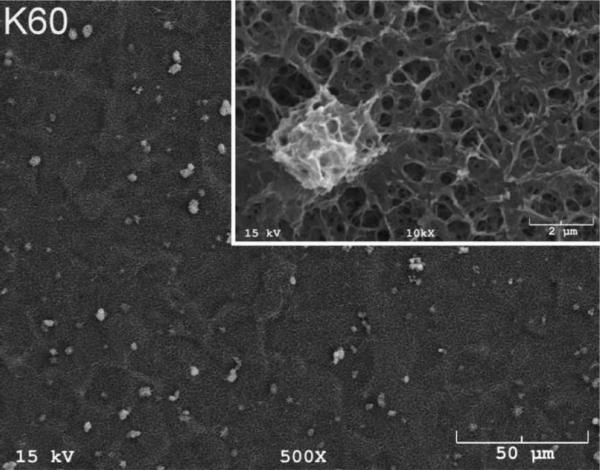

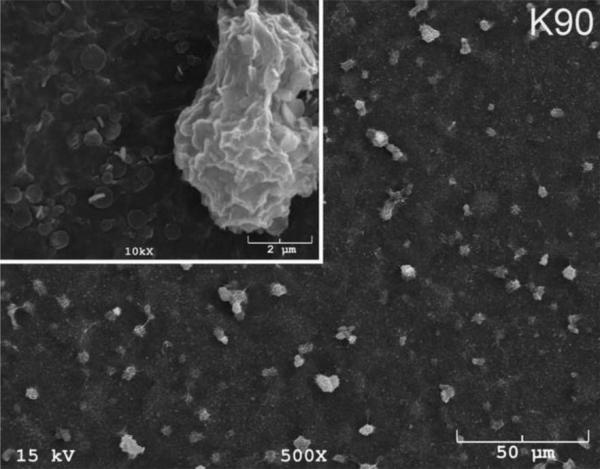

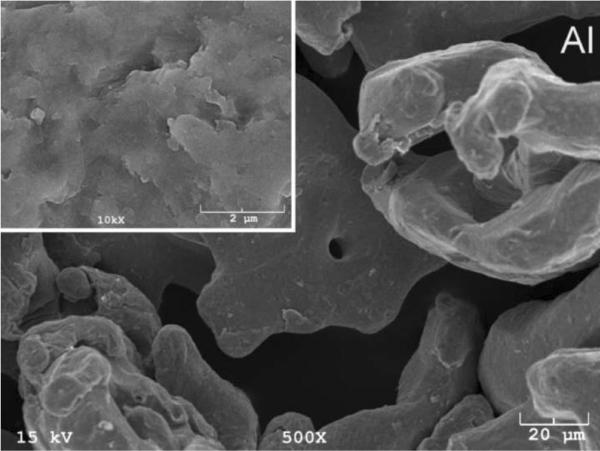

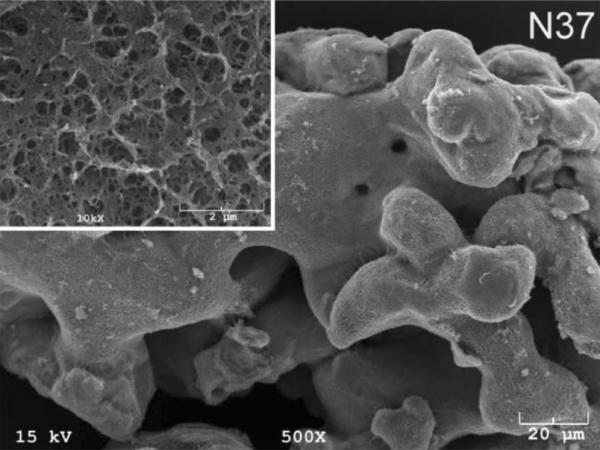

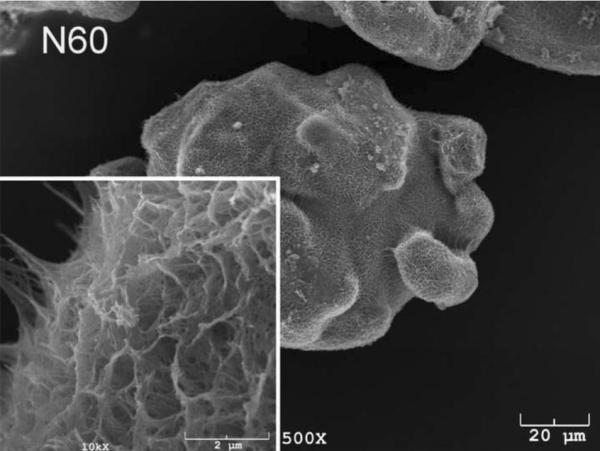

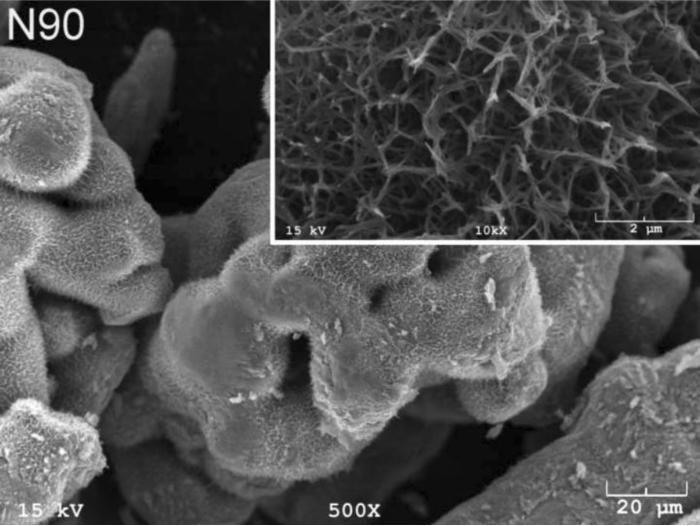

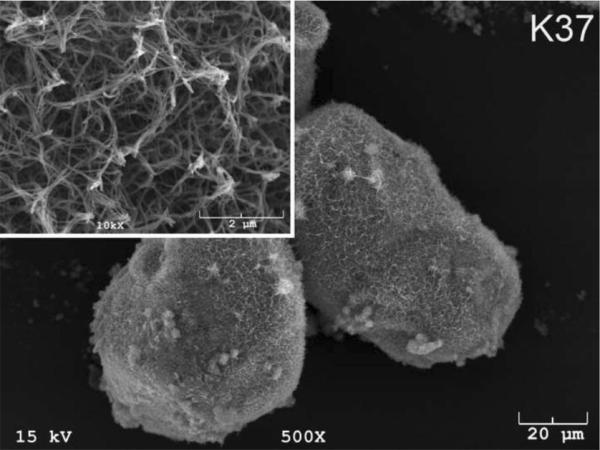

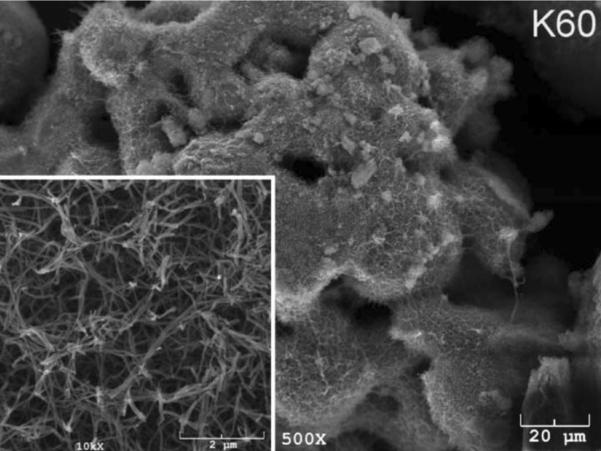

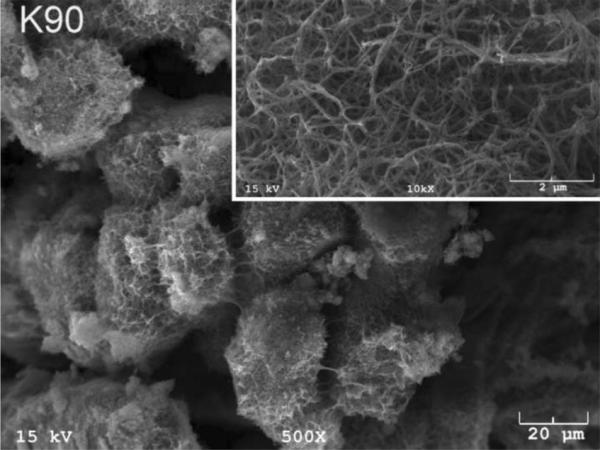

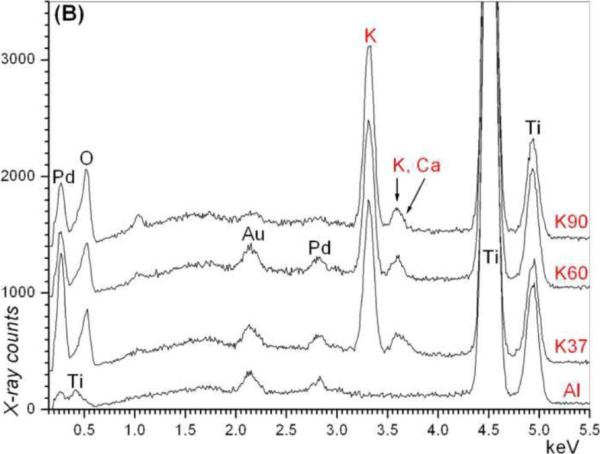

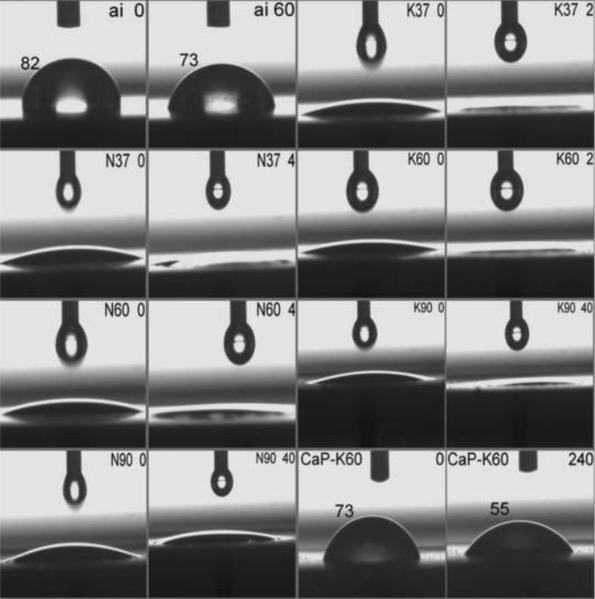

The SEM photomicrographs in Figure 1 depicted the variation in the surface topography of Ti samples (both in sheet/coupon, Fig. 1a, and powder form, Fig. 1b) by changing the alkali solution and treatment temperature. The as is (ai, as received) Ti samples had relatively smooth surfaces. The surfaces of the as is samples were not altered by grinding or polishing. NaOH- and KOH-treated Ti samples showed the formation of a porous and submicron texture even starting at the lowest treatment temperature of 37°C (Fig. 1). All the insets of Figures 1a and 1b were the higher magnification images of the samples. The qualitative EDXS data of Figs. 2a and 2b indicated that Na or K was incorporated into the microstructure, regardless of the sample form, whether they were coupons or powders, following the NaOH or KOH treatments. It was also interesting to note that both series of Na- and K-samples contained small but still detectable amounts of calcium, which might have originated from the glass beakers in which the alkali solutions were initially prepared.

Fig. 1a.

SEM photomicrographs of Ti coupons soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH (e.g., the legend N37 meant a sample soaked in 5 M NaOH at 37°C, whereas AI meant as is)

Fig. 1b.

SEM photomicrographs of Ti powders soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH (e.g., the legend N37 meant a sample soaked in 5 M NaOH at 37°C, whereas AI meant as is)

Fig. 2.

EDXS data of Ti coupons soaked in (a) 5 M NaOH and (b) 5 M KOH solutions (e.g., N37 = 5 M NaOH, 37°C and AI = Ti coupon not soaked in alkali solutions)

Fig. 3.

Contact angle measurements on Ti coupons (e.g., N37=5 M NaOH-37°C, CaP-K60= 5 M KOH-60°C plus amorphous CaP-coated; numbers at the top right corner of frames denoted the time in seconds after the sessile drop touched the surface; t=0 meaning the very first frame captured at the movie recording rate of 25 fps). No difference was detected between, for instance, the photo frame given at the 4th sec and the frame captured at the end of the 15 min movie.

Fig. 1 shows that while the NaOH-soaked samples (at all temperatures) exhibit a porous but rather cellular-looking morphology, KOH-treated samples display unique microstructures consisting of a network of tangled nanotubes or nanofibers. The formation of such nanotubes and nanofibers of titanates were previously reported especially when researchers selected submicron titanium dioxide (TiO2) powders as the starting material for the NaOH or KOH treatments [31, 38–41]. Bavykin et al. [39] reported the synthesis of titanate nanotubes after vigorously stirring submicron TiO2 (anatase form) powders at 100°C for 48 h with relatively high surface areas (148 m2/g for 10 M NaOH and 115 m2/g for 10 M KOH). Yin and Zhao [40], on the other hand, studied the formation of titanate nanotubes in 10 M NaOH or 10 M KOH solutions by heating an amorphous titania gel in autoclaves at 90°, 110°, 130° and 150°C for 72 hours. Sikhwivhilu et al. [41] used submicron TiO2 (rutile form with BET surface area of 50 m2/g) powders and heated those in 5, 10 and 18 M NaOH or KOH solutions at 120° or 150°C, obtaining titanate nanotubes with surface area values ranging from 90 to 260 m2/g.

Ti powders used in this study had the initial surface area less than 0.05 m2/g owing to their quite large particle sizes (ca 100 μm, Fig. 1) and since this study was investigating the alkali treatments at much lower temperatures, the surface areas of Ti samples soaked in static 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions were normally much lower than those reported by the previous literature. BET surface area measurements performed on the Ti powder samples show a significant difference on the ability of 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions in increasing the surface area of Ti powders. BET data (one sample) are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

BET surface area of Ti powders soaked in 5 M NaOH or KOH solutions

| Sample | Surface area (m2/g) |

|---|---|

| Ti - as is | < 0.05 |

| N37 (5 M NaOH – 37°C) | 2.50 |

| N60 | 2.50 |

| N90 | 3.65 |

| K37 (5 M KOH – 37°C) | 6.74 |

| K60 | 8.45 |

| K90 | 10.95 |

At every temperature studied, 5 M KOH solutions increased the surface area of Ti powders compared to 5 M NaOH solutions (Table 2). To the best of our knowledge, this has been the first study to show the difference between NaOH and KOH solutions in increasing the surface area of Ti powders at temperatures less than 100°C. Composites of hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) powders and titanium metal particles were previously studied [42–44], and the alkali-treated, higher surface area Ti particles could be an alternative starting material in preparing such inorganic-metal hybrids.

To determine if 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH solution treatments (from 37° to 90°C) of Ti metal coupons/plates render the resultant surfaces hydrophilic, equilibrium contact angle goniometry experiments were performed. Fig. 3 compares the surface wettability (by deionized water at RT) of all the coupon samples of this study. The data of the contact angle goniometry runs were recorded in the form of 15 minute-long movies. The as is (ai) Ti coupons were not hydrophilic, as the contact angle at the moment of the touch of the sessile drop to the Ti-ai surface was 82° and it only dropped to 73° after 60 s. Contact angle on a surface is defined by the Young equation and the shape of a drop resting on a surface depends on the material properties of the drop, the atmosphere surrounding it, and perhaps most importantly the surface on which it was placed [45]. The data in Fig. 3, therefore, are able to distinguish between different substrate surfaces according to their surface wettability when deionized water at RT was used as the liquid. If one compared all the t=0 frames (see Fig. 3 caption) of alkali-soaked samples with that of “Ti as is,” it would be apparent that alkali treatments increased the wettability of the surfaces. In all the t=0 frames of N- and K-series, the initial contact angle was less than 11°, and with the passage of time, for instance, only 2 or 4 s, the initial drop spread almost fully on the surface, indicating the hydrophilic character of the alkali-treated surfaces. CaP-coating on the alkali-treated samples drastically reduced that hydrophilic character, with the contact angles seen on photos.

N90 and K90 (Fig. 1) samples showed the presence of crystals on the surfaces and, especially in the case of N90 samples, those large crystals probably forced the droplet to remain in the Cassie state [46] meaning that air trapped in between the crystal facets cause a slight decrease in the superhydrophilic character of the N90 samples, in comparison to, for instance, those of N37 and K60. N90 and K90 samples exemplified rough hydrophilic surfaces (Fig. 1). The high value of the contact angle of water on CaP-coated K60 samples (i.e., 73° to 55° in Fig. 3) is in relatively good agreement with the one reported (64°) by Yang et al. [47] for hydroxyapatite surfaces. To the best of our knowledge, this has been the first study to report the results of contact angle measurements on Ti samples soaked in 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH aqueous solutions.

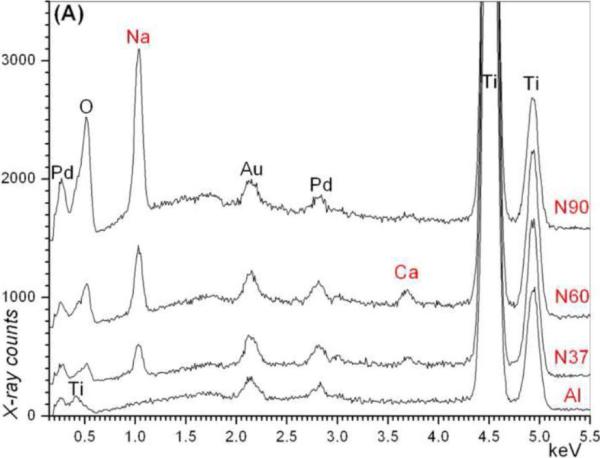

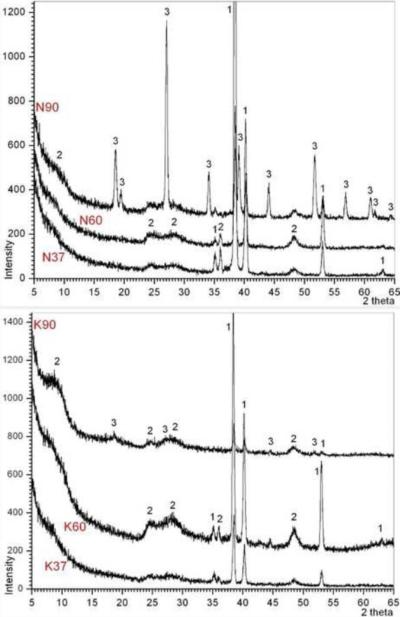

X-ray diffraction is an indispensable tool in determining the phase assemblage of materials, however, in the conventional Bragg-Brentano powder diffractometer geometry the incoming x-rays penetrate the sample deeply making it difficult to distinguish between the phases present at the surface and the bulk of the samples. Since the Ti samples soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH solutions throughout this study produced surface coating nanotubes or nanowires as shown in Fig. 1, grazing incidence x-ray diffraction (GIXRD) was chosen to probe the phase assemblage of the surface phases. Figure 4 summarizes the GIXRD data of Ti coupons soaked in 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions at different temperatures.

Fig. 4.

GIXRD data of Ti coupons soaked in 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH solutions (1: Ti, 2: Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 or K2Ti2O4(OH)2, 3: a phase with a crystal structure similar to the mineral Kassite (CaTi2O4(OH)2))

Three crystalline phases were identified in the data of Fig.4. The first of these phases was titanium. Titanium peaks (labeled 1 in Fig. 4, ICDD-PDF 44-1294) are the result of diffraction by the metal coupon. The second phase in (labeled 2 in Fig. 4) belonged to the phase of nanotubes or nanowires seen (Fig. 1) on the surface of alkali-soaked Ti samples. This phase should either have the formula of Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 (ICDD-PDF 57–0123) or K2Ti2O4(OH)2 (ICDD-PDF 56–0687 and Ref. 34), depending on the alkali solution the sample was immersed in. Yang et al. [48] synthesized Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 nanotubes by stirring TiO2 powders in concentrated NaOH solutions at 110°C for 20 h and reported its XRD data. Na2Ti2O4(OH)2 has a crystal structure similar to that of H2Ti2O4(OH)2 [49]. The third phase (labeled 3 in Fig. 4) was first encountered on the surfaces of N90 samples (rosette-shaped large crystals shown in Fig. 1). It was of high crystallinity and its peaks resembled a phase with a crystal structure quite similar to that of the mineral kassite (CaTi2O4(OH)2), defined by ICDD PDF 57–0596, 72–6913, or 88–1722 [50–52]. Chen et al. [53] prepared the nanotubes again by reacting TiO2 powders with NaOH solutions, analyzed the samples by XRD, and obtained a very similar XRD pattern as Yang et al. [48], and hypothesized that the nanotubes could have the trititanate formula of H2Ti3O7, free of Na. If a sample was ever found to contain Na, by chemical analysis, such a formula free of Na may not be adequate [54, 55].

The synthesis practices and procedures of this study related to the alkali solution soaking did not include Ca2+, nevertheless, the presence of small amounts of Ca was detected in all of our samples as supported by EDXS data (Fig. 2). This was probably due to the use of glass beakers, for a few minutes, in dissolving the solid NaOH or KOH pellets in water to prepare the 5 M NaOH or KOH solutions, which were then transferred into the HDPE bottles for 24 h soaking runs. The dissolution of NaOH or KOH in water is exothermic and the temperature instantly rose to around 60°C in those beakers, probably resulting in the unintentional leaching of some Ca2+ ions from the glass into the solutions at the extremely high pH values (≥13.5) of such solutions. Indeed, analysis of 5M NaOH prepared in glass beakers demonstrated that ~800 nM Ca was preferentially leached from glass containers after 15 minutes compared with identical solutions prepared in plastic. The presence of Ca on the sample surfaces (Fig. 2) could have triggered the crystallization of a phase similar to kassite but perhaps with extensive monovalent alkali cation substitutions over the Ca sites of the kassite-type structure. Although the K90 samples did not possess those rosette-shaped large crystals (Fig. 1), their GIXRD data (Fig. 4) exhibited the low intensity peaks (labeled 3) of the same phase. The experimental methods and the scope of this study unfortunately did not enable us to carefully analyze the chemical composition of those rosette-shaped large crystals.

The nanotubes formed on Ti metal coupons in this study and those synthesized by previous researchers [48–55] by mainly using TiO2 powders as the starting material seems to have one common point: they are not hard-fired ceramic phases in the conventional sense, they contain hydroxyl ions or water molecules or even H in their formula, they are hydrophilic, and unfortunately their in vitro solubility or biocompatibility are not well known or studied. However, some researchers [18–27] always add a heat treatment step (typically performed at 600°C for 1 h) to the process of NaOH-soaking of Ti, causing thermal decomposition of these high surface area nanotubes, transforming them into ceramic oxides (i.e., titanates) containing either Na or K depending on the alkali solution treatment they previously received. Such a phase change to the ceramic oxide form may cause a decrease in their in vitro solubility, and thus the transformation from “wet, hydrated nanotubes” to “ceramic titanates” warrants more research in this field.

A plausible model to explain the solution formation of titanate nanotubes has been previously offered by Bavykin et al. [54]. According to this model, the Ti metal surface will first be rapidly oxidized into TiO2 upon immersion into the alkali solution. The passage from Ti to TiO2 would then proceed with the formation of TiO2 nanosheets on the metal surface, which may then stack upon one another. One can also consider here the peeling off of titania or titanate sheets from a disordered or fragmented raw material initially formed, thus providing bendable sheets [56], which may serve as precursors for the formation of a tangled network of nanotubes (Fig. 1). Na+ or K+ ions present in the alkali aqueous media could also participate in the formation of those titania nanosheets, and the size difference between Na+ (0.095 nm) and K+ (0.133 nm) may have a strong influence on their ability to intercalate. This probably explains why we observed a difference in the surface morphology of Ti treated in NaOH versus those treated in KOH (Fig. 1). The formed sheets would finally go through a process of scrolling or wrapping, mainly to minimize their surface energy, leading to the formation of nanotubes.

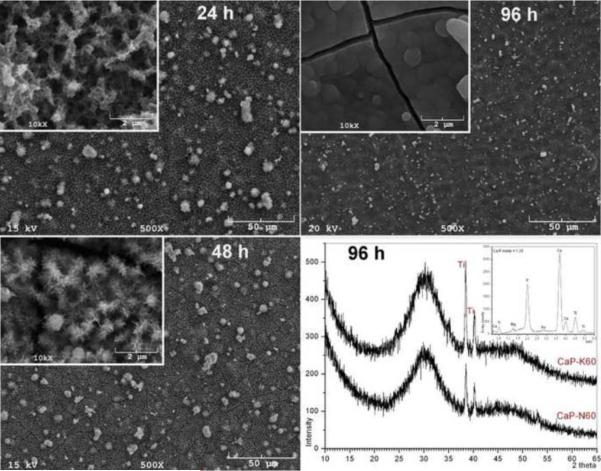

We have hereby suggested a simple solution to coat amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) on the surfaces of alkali-treated Ti. ACP has a higher bioactivity than stoichiometric hydroxyapatite bioceramic owing to its disordered structure and higher solubility [57, 58]. The solution (i.e., BM-7 [37]) used for this purpose was free of any organic buffer, such as Tris or Hepes. Tris, by being a strong buffering agent present in significant amounts in supersaturated calcification solutions (such as SBF, synthetic body fluid [22]), was recently shown by Rohanova et al. [59] to significantly interfere with the nature and sequence of phases to be nucleated on substrates immersed into the Tris-buffered SBF solutions to test their in vitro bioactivity. BM-7 solution does not have any buffering agent, it has the same HCO3- concentration as those of the cell culture solution DMEM and has a Ca/P molar ratio of 2.5 identical with that of human blood plasma. Figure 5 shows the progress of ACP coating of K60 samples as a function of time at 37°C in BM-7 solutions. Until now, all formulations of SBF solutions were able to deposit only hydroxyapatite-like cryptocrystalline calcium phosphate on Ti substrates [18–27]; the solution suggested here was able to coat ACP, for the first time, on Ti.

Fig. 5.

Amorphous CaP-coated K60 (and N60, XRD) samples with BM-7 solution at 37°C (soaking times in BM-7 solution were indicated on the micrographs)

K60 samples soaked in the BM-7 solution for only 24 h showed the deposition of CaP onto the Ti nanotubes (Fig. 5). The sample kept in the BM-7 solution for 48 h showed more extensive coverage of the Ti nanotubes with CaP. However, the increase in soaking time at 37°C from 48 h to 96 h had the most drastic influence on the surface coverage, and the entire surface was covered with ACP, as shown in the GIXRD data of Fig. 5. The 96 h sample was directly washed with deionized water upon its removal from the BM-7 solution, followed by drying in air. The cracks seen in the SEM photo of Fig. 5 were unfortunately due to rapid drying; such samples should first be dehydrated through sequential ethanol rinses, prior to their placement into the vacuum chamber of the electron microscope [60]. The 96 h-K60 samples of Fig. 5 were not hydrophilic as proved before by the contact angle goniometry data presented in Fig. 3. These ACP-coated samples, which happened to be the first ACP-coatings on Ti obtained by a biomimetic method (according to the popular wording accepted for the SBF coatings) were mainly prepared to test their behavior during the in vitro cell culture studies performed with the osteoblast-like cells. The EDXS chart shown in the inset of the GIXRD data of Fig. 5 confirmed that the deposited ACP layers had a Ca/P molar ratio of around 1.38. This Ca/P molar is quite similar to the ratio of newborn chicks [61]. In ACP synthesis experiments performed at 30° and 42°C, the Ca/P molar ratio of the amorphous phase formed in solutions varied between 1.35 and 1.38 [62].

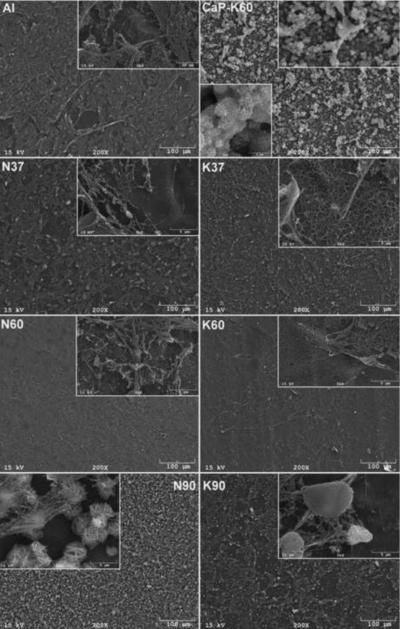

In vitro cell culture tests showed that cells were readily attaching, spreading and proliferating on all the samples of this study. The SEM photomicrographs of Fig. 6 were captured to evaluate the extent of cell attachment and spreading. Ti-as is samples showed (Fig. 6) quite extensive cell attachment and spreading. Within the set of NaOH-soaked Ti samples, cell attachment and spreading declined (Fig. 6) significantly with treatment temperature over 37°C. SEM photomicrographs of KOH-soaked Ti samples also show reduced cell adhesion and spreading apparent even at 37°C. Cells were extending their filopodia on the surfaces and covering the nanotubes.

Fig. 6.

SEM photomicrographs of coupons after the in vitro cell culture study showing the cell attachment and differentiation

At 72 h of tissue culture, the surface morphology of the ACP-coated 96 h-K60 sample (Fig. 6) significantly changed (in comparison to that shown in Fig. 5). The Ca/P molar ratio of these ACP 96h-K60 cell culture samples reduced slightly to about 1.29 by EDXS analyses. This suggests that the morphological change was combined with a slight change in chemistry as well. The rapid morphological change identified here has not been previously noted [63]. Importantly, the ACP-coated Ti sample of Fig. 6 shows early in vitro biomineralization. Heat-treated (such as temperatures ≥600°C) calcium phosphate coatings on Ti failed to show this kind of rapid in vitro biomineralization [64]. Of note, the highest temperature the ACP-coated Ti samples in this study have been heated at was 37°C, i.e., the human body temperature.

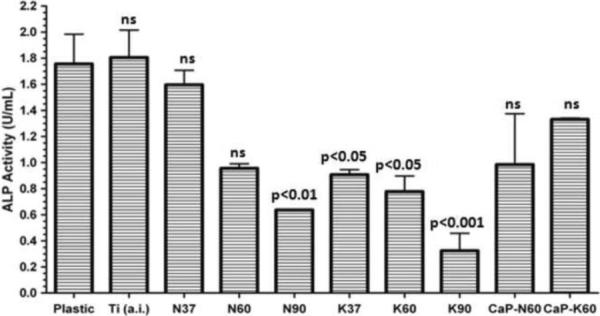

To determine whether the cells attached to the treated Ti samples were maturing into osteoblasts, we quantified the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity. ALP activity (Fig. 7) confirmed that the coupons sustained functional osteoblasts with as is Ti being similar to plastic or N37 treated Ti. ALP activity confirmed that the cells present on the KOH treated or higher temperature NaOH-treated samples were still functional despite their fewer numbers as seen in Figure 6. The overall ALP activity displayed by the K-group was much less than that of the N-group at all treatment temperatures tested. ALP activity of the ACP-coated samples was higher than the entire K-group. Thus, increasing temperature above 37°C induced significant reductions in cell attachment and spreading as well as ALP activity.

Fig. 7.

Alkaline phosphatase activity of osteoblast-like cells cultures on coupons. P values determined by one way ANOVA comparing Ti versus each other treatment. ns=non-significant (Plastic: tissue culture polystyrene)

The cause in the decline of ALP activity with increasing temperature within each group (either N-group or K-group) is not entirely clear. Yang et al. [48] proposed that Na+ and K+ ions found in the nanotubes on Ti surfaces might leach away from the nanotubes at neutral pH values. If so, then the cells attached would face an influx of those ions originating from the substrates themselves that might lead to altered cellular attachment and differentiation with a decline in alkaline phosphatase production. However, under these conditions NaOH treatment at 37°C or KOH treatment at 60°C coupled with amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) coating still maintain cellular differentiation.

The research efforts focusing on the bioactivation of titanium surfaces, including the development of methods to increase the surface area and hydrophilic character of the substrates, were aimed at improving the in vivo bonding between the natural bone and the metallic implant which may greatly help to reduce particulate materials to result from the wear-corrosion phenomena the implant may undergo [65, 66].

Cell attachment, which is the first step in bone tissue formation, to titanium implants usually follows the binding of blood or cell (odontoblasts or osteoblasts)-produced proteins (such as fibronectin) to the available surfaces [67]. As shown in this study, static immersion in NaOH or KOH solutions increased the BET surface area of titanium (Table 2) and changed the hydrophobic surfaces of the as received cpTi coupons to hydrophilic (Fig. 3). An increase in the BET surface area of a synthetic biomaterial correlates to increased availability of binding sites for proteins. Moreover, Eriksson et al. [68] reported in an animal study that the implanted hydrophilic Ti discs (produced by boiling Ti samples in a H2O2-NH4OH-H2O solution) were able to bind more bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and viable cells on their surfaces within the first 8 days of implantation than the hydrophobic Ti discs (produced by ultrasonication in a water-butanol solution). Prior to the current study surface wettability (quantitatively determined via contact angle measurements) of cpTi samples immersed in different alkali solutions was not available. Titanium implants with hydrophilic and high BET-value surfaces are good candidates for the delivery of pharmacologic agents as well.

Titanium implants used in oral and orthopedic surgery are usually coated with bioinert (e.g., alumina) or bioactive (calcium phosphate) ceramics to improve their osteointegrative capability and surface roughness. Prior to this study, there was no means of coating cpTi at the human body temperature of 37°C with x-ray amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) by static immersion in precipitate-free, carbonated calcium phosphate solutions similar in composition to the electrolyte portion of human blood plasma. The solution (Table 1) used here to coat cpTi, for the first time, with ACP may also be used to coat other bioceramics, metals and biopolymers with an ACP layer. The state-of-the-art (prior to this study) in the solution coating of titanium implants at 37°C was only able to deposit layers of poorly crystalline (namely, cryptocrystalline) apatitic calcium phosphate [22, 62]. On the other hand, there is strong evidence that in biological systems [69] and in calcium-supplemented synthetic osteogenic media [70], the formation of cryptocrystalline calcium phosphate seems to be preceded by the formation of nano-aggregates of an amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) precursor. The current study, therefore, demonstrated the possibility of biomimetic coating of cpTi implants at 37°C in easy-to-prepare, non-stirred aqueous media with an ACP layer which shall act as a facilitator or precursor (upon in vivo implantation) to the in vivo nucleation of biological apatite on the implant surface.

4. Conclusions

cpTi coupons statically soaked in 5 M NaOH or 5 M KOH aqueous solutions for 24 h at 37°, 60° and 90°C were all found to form nanostructures of hydrated titanate layers on their surfaces. Hydrated titanate layers were characterized by using SEM, EDXS, XRD, contact angle measurements, and in vitro cell culture tests performed with osteoblast-like cells. Contact angle goniometry tests were conducted, for the first time, on alkali-treated metal coupons to show that these simple chemical treatments caused the hydrophobic as received Ti to become hydrophilic. Powder samples of pure Ti were treated in alkali solutions under the same conditions and BET surface area measurements showed that the Ti powders soaked in KOH solutions resulted in much higher surface areas than NaOH-soaked samples at all three temperatures. A calcification solution free of any organic buffers was used to coat the alkali-treated Ti coupons at 37°C in 96 h with a layer of amorphous calcium phosphate for the first time. Osteoblast-like cells cultured for 72 h on treated Ti coupons differentiated and produced alkaline phosphatase but KOH treatment or higher temperatures (60° or 90°C) induced declining cell attachment and differentiation.

Highlights

Titanium was treated with 5 M NaOH and 5 M KOH alkali solutions at 37°, 60° and 90°C

Treated Ti was compared with contact angle goniometry, grazing incidence XRD, surface area, SEM and in vitro cell culture tests

A calcification solution was developed for coating Ti at 37°C with an amorphous calcium phosphate layer

Acknowledgements

This study was in part supported by NIH 1-R01-DE19398-01. C. Kim took part at the very beginning of this study as a talented high school (OSSM) senior working under the mentorship of A. C. Tas for 3 months. Authors are grateful to Dr. Sharukh Khajotia (OUHSC) to let Christina Kim use his contact angle goniometer. Authors cordially thank to Dr. John Dmytryk (OUHSC) to allow us to use his laboratories. Authors acknowledge the generous help of Jeremy Jernigen (OU-Norman) in cutting the Ti coupons by using a guillotine-type cutter. A. C. Tas was a visiting professor in the College of Dentistry of University of Oklahoma (OUHSC) between October 2010 and September 2011.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Notes

Certain commercial instruments or materials are identified in this article solely to foster understanding. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the authors, nor does it imply that the instruments or materials identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

References

- [1].Long M, Rack HJ. Titanium alloys in total joint replacement – a materials science perspective. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1621–1639. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].de Groot K, Geesink RGT, Klein CPAT, Serekian P. Plasma sprayed coatings of hydroxyapatite. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1987;21:1375–1387. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820211203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ducheyne P, Radin S, Heughbaert M, Heughbaert JC. Calcium phosphate ceramic coating on porous titanium: effect of structure and composition on electrophoretic deposition, vacuum sintering and in vitro dissolution. Biomaterials. 1990;11:244–254. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(90)90005-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Takatsuka K, Yamamuro T, Kitsugi T, Nakamura T, Shibuya T, Goto T. A new bioactive glass-ceramic as a coating material on titanium alloy. J. Appl. Biomater. 1993;4:317–329. doi: 10.1002/jab.770040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Klein CPAT, Patka P, van der Lubbe HBM, Wolke JGC, de Groot K. Plasma sprayed coating of tetracalcium phosphate, hydroxylapatite, and a-KNIGHT on titanium alloy: an interfacial study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1991;25:53–65. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820250105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hench LL, Paschall HA. Direct chemical bond of bioactive glass-ceramic materials to bone and muscle. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1973;7:25–42. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820070304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Martin JY, Schwartz Z, Hummert TW, Schraub DM, Simpson J, Lankford JJ, Dean DD, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. Effect of titanium surface roughness on proliferation, differentiation, and protein synthesis of human osteoblast-like cells (MG63) J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1995;29:389–401. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vroman L. Finding seconds count after contact with blood (and that is all I did) Colloid. Surface. B. 2008;62:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nygren H. Initial reactions of whole blood with hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces. Colloid. Surface. B. 1996;6:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eriksson C, Nygren H. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes in coagulating whole blood recognize hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces by different adhesion receptors and show different patterns of receptor expression. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2001;137:296–302. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.114066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Martin JY, Dean DD, Cochran DL, Simpson J, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Proliferation, differentiation, and protein synthesis of human osteoblast-like cells (MG63) cultured on previously used titanium surfaces. Clin. Oral Implan Res. 1996;7:27–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhao G, Zinger O, Schwartz Z, Wieland M, Landolt D, Boyan BD. Osteoblast-like cells are sensitive to submicron-scale surface structure. Clin. Oral Implan. Res. 2006;17:258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Hutton DL, Erdman CP, Wieland M, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Direct and indirect effects of microstructured titanium substrates on the induction of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards the osteoblast lineage. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2728–2735. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gittens RA, McLachlan T, Olivares-Navarrete R, Cai Y, Berner S, Tannenbaum R, Schwartz Z, Sandhage KH, Boyan BD. The effects of combined micron/submicron-scale surface roughness and nanoscale features on cell proliferation and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3395–3403. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Klein MO, Bijelic A, Toyoshima T, Goetz H, von Koppenfels RL, Al-Nawas B, Duschner H. Long-term response of osteogenic cells on micron and submicron-scale-structured hydrophilic titanium surfaces: sequence of cell proliferation and cell differentiation. Clin. Oral Implan Res. 2010;21:642–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhang Y, Andrukhov O, Berner S, Matejka M, Wieland M, Fan XH, Schedle A. Osteogenic properties of hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium surfaces evaluated with osteoblast-like cells (MG63) in coculture with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) Dent. Mater. 2010;26:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Linares A, Mardas N, Dard M, Donos N. Effect of immediate or delayed loading following immediate placement of implants with a modified surface. Clin. Oral Implan. Res. 2011;22:38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kim HM, Miyaji F, Kokubo T, Nakamura T. Preparation of bioactive Ti and its alloys via simple chemical surface treatment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1996;32:409–417. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199611)32:3<409::AID-JBM14>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fujibayashi S, Nakamura T, Nishiguchi S, Tamura J, Uchida M, Kim HM, Kokubo T. Bioactive titanium: effect of sodium removal on the bone-bonding ability of bioactive titanium prepared by alkali and heat treatment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001;56:562–570. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010915)56:4<562::aid-jbm1128>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Uchida M, Kim HM, Kokubo T, Fujibayashi S, Nakamura T. Effect of water treatment on the apatite-forming ability of NaOH-treated titanium metal. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;63:522–530. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nishiguchi S, Fujibayashi S, Kim HM, Kokubo T, Nakamura T. Biology of alkali- and heat-treated titanium implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2003;67A:26–35. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kokubo T, Kim HM, Kawashita M, Nakamura T. Bioactive metals: preparation and properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004;15:99–107. doi: 10.1023/b:jmsm.0000011809.36275.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kawai T, Kizuki T, Takadama H, Matsushita T, Unuma H, Nakamura T, Kokubo T. Apatite formation on surface titanate layer with different Na content on Ti metal. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2010;118:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pattanayak DK, Yamaguchi S, Matsushita T, Kokubo T. Effect of heat treatments on apatite-forming ability of NaOH- and HCl-treated titanium metal. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2011;22:273–278. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pattanayak DK, Yamaguchi S, Matsushita T, Kokubo T. Nanostructured positively charged bioactive TiO2 layer formed on Ti metal by NaOH, acid and heat treatments. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2011;22:1803–1812. doi: 10.1007/s10856-011-4372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim HM, Miyaji F, Kokubo T, Nishiguchi S, Nakamura T. Graded surface structure of bioactive titanium prepared by chemical treatment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999;45:100–107. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199905)45:2<100::aid-jbm4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tas AC, Bhaduri SB. Rapid coating of Ti6Al4V at room temperature with a calcium phosphate solution similar to 10× simulated body fluid. J. Mater. Res. 2004;19:2742–2749. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ito T, Hayata K, Sugimoto T. Surface modification of titanium alloys by coating with anatase-type TiO2. J. Jpn. Inst. Metals. 2006;70:936–939. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tanaka SI, Tobimatsu H, Maruyama Y, Tanaki T, Jerkiewicz G. Preparation and characterization of microporous layers on titanium. Appl. Mater. Interf. 2009;1:2312–2319. doi: 10.1021/am900474h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee SY, Takai M, Kim HM, Ishihara K. Preparation of nano-structured titanium oxide film for biosensor substrate by wet corrosion process. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2009;9:e266–e269. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee SY, Matsuno R, Ishihara K, Takai M. Electrical transport ability of nanostructured potassium-doped titanium oxide film. Appl. Phys. Express. 2011;4:025803. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Giannoni P, Muraglia A, Giordano C, Narcisi R, Cancedda R, Quarto R, Chiesa R. Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells on surface-modified titanium alloys for orthopedic and dental implants. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2009;32:811–820. doi: 10.1177/039139880903201107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cai K, Lai M, Yang W, Hu R, Xin R, Liu Q, Sung KL. Surface engineering of titanium with potassium hydroxide and its effects on the growth behavior of mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2314–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Masaki N, Uchida S, Yamane H, Sato T. Hydrothermal synthesis of potassium titanates in Ti-KOH-H2O system. J. Mater. Sci. 2000;35:3307–3311. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Masaki N, Uchida S, Yamane H, Sato T. Characterization of a new potassium titanate, KTiO2(OH) synthesized via hydrothermal method. Chem. Mater. 2002;14:419–424. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bans S. Effect of alkaline treatment of pure titanium and its alloys on the bonding strength of dental veneering resins. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2003;66A:138–145. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Temizel N, Girisken G, Tas AC. Accelerated transformation of brushite to octacalcium phosphate in new biomineralization media between 36.5° and 80°C. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2011;31:1136–1143. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yuan ZY, Su BL. Titanium oxide nanotubes, nanofibers and nanowires. Colloid. Surface. A. 2004;241:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bavykin DV, Cressey BA, Light ME, Walsh FC. An aqueous, alkaline route to titanate nanotubes under atmospheric pressure conditions. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:275604. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/27/275604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yin J, Zhao XP. Facile synthesis and the sensitized luminescence of europium ions-doped titanate nanowires. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009;114:561–568. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sikhwivhilu LM, Ray SS, Coville NJ. Influence of bases on hydrothermal synthesis of titanate nanostructures. Appl. Phys. A. 2009;94:963–973. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chang Q, Chen DL, Ru HQ, Yue XY, Yu L, Zhang CP. Toughening mechanisms in iron-containing hydroxyapatite/titanium composites. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Huang J, Best SM, Bonfield W, Buckland T. Development and characterization of titanium-containing hydroxyapatite for medical applications. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kodama A, Bauer S, Komatsu A, Asoh H, Ono S, Schmuki P. Bioactivation of titanium surfaces using coatings of TiO2 nanotubes rapidly pre-loaded with synthetic hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:2322–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tadmor R. Line energy and the relation between advancing, receding, and Young contact angles. Langmuir. 2004;20:7659–7664. doi: 10.1021/la049410h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Whyman G, Bormashenko E. How to make the Cassie wetting state stable? Langmuir. 2011;27:8171–8176. doi: 10.1021/la2011869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yang Y, Paital SR, Dahotre NB. Effects of SiO2 substitution on wettability of laser deposited Ca-P biocoating on Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2010;21:2511–2521. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yang J, Jin Z, Wang X, Li W, Zhang J, Zhang S, Guo X, Zhang Z. Study on composition, structure and formation process of nanotube Na2Ti2O4(OH)2. Dalton T. 2003;20:3898–3901. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tsai CC, Teng H. Structural features of nanotubes synthesized from NaOH treatment on TiO2 with different post treatments. Chem. Mater. 2006;18:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Self PG, Buseck PR. Structure model for kassite, CaTi2O4(OH)2. Am. Mineral. 1991;76:283–287. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Huang YJ, Tsai MC, Chiu HT, Sheu HS, Lee CY. Artificial synthesis of platelet-like kassite and its transformation to CaTiO3. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010;10:1221–1225. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Li X, Zhou Q, Wang H, Peng Z, Liu G. Hydrothermal formation and conversion of calcium titanate species in the system Na2O-Al2O3-CaO-TiO2-H2O. Hydrometallurgy. 2010;104:156–161. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chen Q, Du GH, Zhang S, Peng LM. The structure of trititanate nanotubes. Acta Crystallogr. B. 2002;58:587–593. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102009084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bavykin DV, Parmon VN, Lapkin AA, Walsh FC. The effect of hydrothermal conditions on the mesoporous structure of TiO2 nanotubes. J. Mater. Chem. 2004;14:3370–3377. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Peng CW, Plouet MR, Ke TY, Lee CY, Chiu HT, Marhic C, Puzenat E, Lemoigno F, Brohan L. Chimie douce route to sodium hydroxo titanate nanowires with modulated structure and conversion to highly photoactive titanium dioxides. Chem. Mater. 2008;20:7228–7236. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Morgado E, de Abreu MAS, Moure GT, Marinkovic BA, Jardim PM, Araujo AS. Characterization of nanostructured titanates obtained by alkali treatment of TiO2-anatases with distinct crystal sizes. Chem. Mater. 2007;19:665–676. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Spies CKG, Schnuerer S, Gotterbarm T, Breusch S. The efficacy of Biobon and Ostim within metaphyseal defects using the Goettinger minipig. Arch. Orthop. Traum. Su. 2009;129:979–988. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Linhart W, Briem D, Schmitz ND, Priemel M, Lehmann W, Rueger JM. Treatment of metaphyseal bone defects after fractures of the distal radius. Medium-term results using a calcium phosphate cement (Biobon) Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:618–624. doi: 10.1007/s00113-003-0628-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Rohanova D, Boccaccini AR, Yunos DM, Horkavcova D, Brezovska I, Helebrant A. TRIS buffer in simulated body fluid distorts the assessment of glass-ceramic scaffold bioactivity. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2623–2630. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Jalota S, Bhaduri S, Bhaduri SB, Tas AC. A protocol to develop crack-free biomimetic coatings on Ti6Al4V substrates. J. Mater. Res. 2007;22:1593–1600. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cazalbou S, Combes C, Eichert D, Rey C, Glimcher MJ. Poorly crystalline apatites: evolution and maturation in vitro and in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2004;22:310–317. doi: 10.1007/s00774-004-0488-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Combes C, Rey C. Amorphous calcium phosphates: Synthesis, properties and uses in biomaterials. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3362–3378. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Jalota S, Bhaduri SB, Tas AC. Osteoblast proliferation on neat and apatite-like calcium phosphate-coated titanium foam scaffolds. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2007;27:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- [64].Brugge PJ, Dieudonne S, Jansen JA. Initial interaction of U2OS cells with noncoated and calcium phosphate coated titanium substrates. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2002;61:399–407. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Rubio JC, Alonso MCG, Alonso C, Alobera MA, Clemente C, Munuera L, Escudero ML. Determination of metallic traces in kidneys, livers, lungs and spleens of rats with metallic implants after a long implantation time. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008;19:369–375. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Urban RM, Tomlinson MJ, Hall DJ, Jacobs JJ. Accumulation in liver and spleen of metal particles generated at non-bearing surfaces in hip arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 2004;19:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].MacDonald DE, Markovic B, Allen M, Somasundaran P, Boskey AL. Surface analysis of human plasma fibronectin adsorbed to commercially pure titanium materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998;41:120–130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199807)41:1<120::aid-jbm15>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Eriksson C, Nygren H, Ohlson K. Implantation of hydrophilic and hydrophobic titanium discs in rat tibia: cellular reactions on the surfaces during the first 3 weeks in bone. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4759–4766. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Mahamid J, Sharir A, Addadi L, Weiner S. Amorphous calcium phosphate is a major component of the forming fin bones of zebrafish: indications for an amorphous precursor phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:12748–12753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803354105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sargeant TD, Aparicio C, Goldberger JE, Cui H, Stupp SI. Mineralization of peptide amphiphile nanofibers and its effect on the differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:2456–2465. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]