Summary

Background and objectives

Previous reports of Fabry disease screening in dialysis patients indicate that α-galactosidase A activity alone cannot specifically and reliably identify appropriate candidates for genetic testing; a marker for secondary screening is required. Elevated plasma globotriaosylsphingosine is reported to be a hallmark of classic Fabry disease. The purpose of this study was to examine the usefulness of globotriaosylsphingosine as a secondary screening target for Fabry disease.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This study screened 1453 patients, comprising 50% of the male dialysis patients in Niigata Prefecture between July 1, 2010 and July 31, 2011. Screening for Fabry disease was performed by measuring the plasma α-galactosidase A enzyme activity and the globotriaosylsphingosine concentration, by high-performance liquid chromatography. Genetic testing and genetic counseling were provided.

Results

A low level of plasma α-galactosidase A activity (≤4.0 nmol/h per milliliter) was observed in 47 patients (3.2%). Of these, 3 (0.2%) had detectable globotriaosylsphingosine levels. These patients all had α-galactosidase A gene mutations: one was p.Y173X and two were the nonpathogenic p.E66Q. The patient with p.Y173X started enzyme replacement therapy. Subsequent screening of his family identified the same mutation in his elder sister and her children. Genetic testing for 33 of the other 44 patients detected 7 patients with p.E66Q. Thus, the plasma lyso-Gb3 screen identified Fabry disease with high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (94.3%).

Conclusions

Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine is a promising secondary screening target that was effective for selecting candidates for genetic counseling and testing and for uncovering unrecognized Fabry disease cases.

Introduction

Fabry disease (FD) is an X-linked lysosomal storage disorder resulting from a deficiency in the activity of α-galactosidase A (α-Gal A) (1), a lysosomal enzyme. This enzyme deficiency causes the systemic lysosomal accumulation of glycolipids, primarily globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), in the vascular endothelium and other tissues. Morbidity and mortality from FD, caused by renal failure, cardiac disease, and early onset stroke, increase with age, and screens of male patients on dialysis show an FD prevalence of 0.2%–1.7% (2–11). The advent of an effective treatment, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), has increased the importance of identifying people with FD.

α-Gal A deficiency screens have used plasma (2,3,6,7) and dried blood spot (5,9–11) samples; low leukocyte α-Gal A activity is also used to identify candidates for further testing (3,5–7,9). Patients positive for the α-Gal A activity screen (i.e., with low activity) are subsequently tested for mutations in the α-Gal A gene (GLA) (2–11). The genetic tests revealed that α-Gal A activity screening lacks specificity, in that some patients without GLA mutations test positive (5,8,10,11). In addition, many females who are heterozygous for pathogenic GLA mutations have normal plasma α-Gal A activity, so screening studies for FD have predominantly focused on male dialysis patients (3,4,6). A secondary screening method to identify FD patients is needed. Ideally, this method would avoid re-sampling or unnecessary genetic testing for FD, which can increase patients’ psychologic distress.

Although Gb3, found in the plasma of control participants (12–15), is not a suitable target for secondary screening, globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3) is dramatically increased in the plasma of male patients with classic FD (12–14), and might therefore be a good secondary screening target (12).

In this study, we screened the male dialysis population of Niigata Prefecture for FD by measuring the plasma α-Gal A activity and lyso-Gb3 concentration and verified the sensitivity and specificity of the lyso-Gb3 screen. The study design included methodologic strategies for reducing patients’ distress.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Lyso-Gb3 Screen.

Male dialysis patients in Niigata Prefecture, Japan, of unknown FD status, were screened for FD between July 1, 2010 and July 31, 2011. All 51 dialysis centers in Niigata Prefecture were invited to participate. Dialysis patients were informed about the study specifics, and those who agreed to participate provided informed consent. The study design involved four steps: (1) Patients were screened for FD by measuring their plasma α-Gal A activity (activity ≤4 nmol/h per milliliter was considered a positive result); (2) patients with positive results for the α-Gal A activity screen were re-tested by measuring their plasma lyso-Gb3; (3) patients with elevated lyso-Gb3 were informed in the context of genetic counseling that they might have FD; and (4) with patient consent, the diagnosis of FD was confirmed by genetic testing of GLA, and familial diagnosis was performed.

Screen Verification.

To determine whether the lyso-Gb3 screen missed patients who had FD, we performed genetic testing on the patients who tested positive in the α-Gal A activity screen, but negative in the lyso-Gb3 screen.

Plasma Samples

To minimize patient distress, we used plasma obtained from a single blood sample collection for both the primary and secondary screening. This procedure reduced the number of times that patients had to endure sampling, permitted the secondary screen to be performed without alarming the patients unnecessarily, and reduced the burden of labor on the institutional staff.

Determination of Plasma α-Gal A Activity

The α-Gal A activity was assayed with an artificial substrate, 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D-galactoside, as described elsewhere (16). The low cutoff value for a positive plasma α-Gal A activity was set as the third percentile value (i.e., 4 nmol/h per milliliter).

Measurement of Plasma Lyso-Gb3

Lyso-Gb3 was extracted from plasma as described (14). The O-phthaldialdehyde–derivatized lyso-Gb3 was separated by high-performance liquid chromatography (Jasco Co., Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan) with a Unison UK-C18 reversed-phase column (150×4.6 mm, 3 μm; Imtakt Co., Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan), and quantified by fluorescence detection at λex 340 nm and λem 435 nm, at a 1.0 ml/min flow rate. The mobile phase was methanol/H2O [88:12 (v/v)]. For quantification, authentic lyso-Gb3 (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) was added to normal plasma.

Genetic Testing

The human GLA consists of seven exons. Exons 1 and 7 were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR, and a fragment containing full-length exons 2–6 and all of the exon-intron boundaries was obtained by RT-PCR using total RNA. The DNA and RNA were extracted from white blood cells. Genetic testing was performed as described elsewhere (17).

Informed Consent and Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Niigata University School of Medicine, Oita University, and the collaborating dialysis centers, and informed consent was obtained from the patients. Separate approval and informed consent were obtained for the verification protocol. The study protocols were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genetic Counseling before and after Genetic Testing

Patients with detectable plasma lyso-Gb3 were considered candidates for genetic testing. The genetic counseling team consisted of two certified specialists in medical genetics, a nephrologist, two certified genetic counselors, two clinical psychologists, and a nurse, all from Niigata University. The principal issues were explained to the examinee, whose consent and comprehension were confirmed by the team before and after genetic testing. The genetic testing performed in this study met the recommendations of the Japanese Association of Medical Sciences (18).

Statistical Analyses

Values are shown as the median and interquartile range (25th to 75th percentiles) or the mean ± SD. A two-sided Fisher’s exact test and chi-squared test were used to evaluate the categorical data. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Study Population

Of the 51 Niigata Prefecture dialysis centers, 31 (61%) participated in this study. Of the total population of male dialysis patients in Niigata Prefecture (n=2905), 1453 (50%), including 1428 on hemodialysis and 25 on peritoneal dialysis, were screened. Participation rate among eligible patients in the dialysis centers was 86.7% (1453 of 1676). Their underlying kidney diseases were chronic GN in 685 patients (47.1%), diabetic nephropathy in 488 patients (33.6%), nephrosclerosis in 142 patients (9.8%), polycystic kidney disease in 62 patients (4.3%), other disease in 63 patients (4.3%), and unknown in 13 patients (0.9%). Their mean age at the time of blood sampling was 66.1±12.0 years (range, 25.3–95.0 years), and was 57.7±15.5 years (range, 12.8–91.4 years) at the start of dialysis. The duration of dialysis was 8.5±8.4 years (range, 0–42.5 years).

Plasma α-Gal A Activity in the Primary Screening

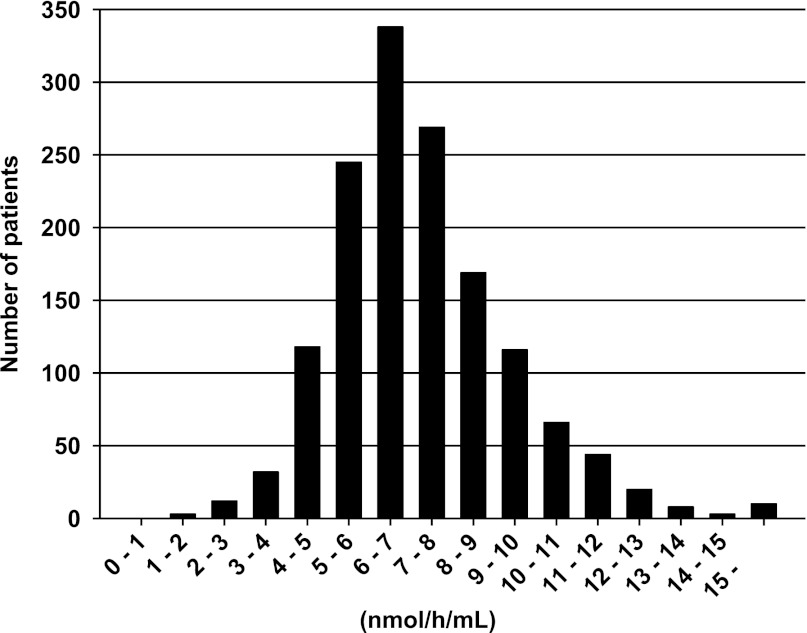

The median plasma α-Gal A activity of all patients was 7.0 nmol/h per milliliter (5.9–8.4 nmol/h per milliliter). In 47 patients, the activity was ≤4.0 nmol/h per milliliter, with a median of 3.4 nmol/h per milliliter (2.9–3.9 nmol/h per milliliter). The median plasma α-Gal A activity in the remaining 1406 patients was 7.1 nmol/h per milliliter (6.0–8.5 nmol/h per milliliter) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of plasma α-Gal A activities for all patients tested (n=1453) in increments of 1 nmol/h per milliliter, plotted against the number of patients with activity in each interval (observed range of activity 1.3–88.3 nmol/h per milliliter; median activity 7.0 nmol/h per milliliter [5.9–8.4 nmol/h per milliliter]). Each interval in the x axis scale refers to the range beginning with the minimum value, but not including the minimum value and extending up to the maximum value. For example, 1–2 means the range beginning at 1, but not including 1 and containing the values up to 2. In 47 patients, the activity was ≤4.0 nmol/h per milliliter, the low cutoff for the test; the median activity in these 47 patients was 3.4 nmol/h per milliliter (2.9–3.9 nmol/h per milliliter). α-Gal A, α-galactosidase A.

Plasma Lyso-Gb3 Levels in the Secondary Screening

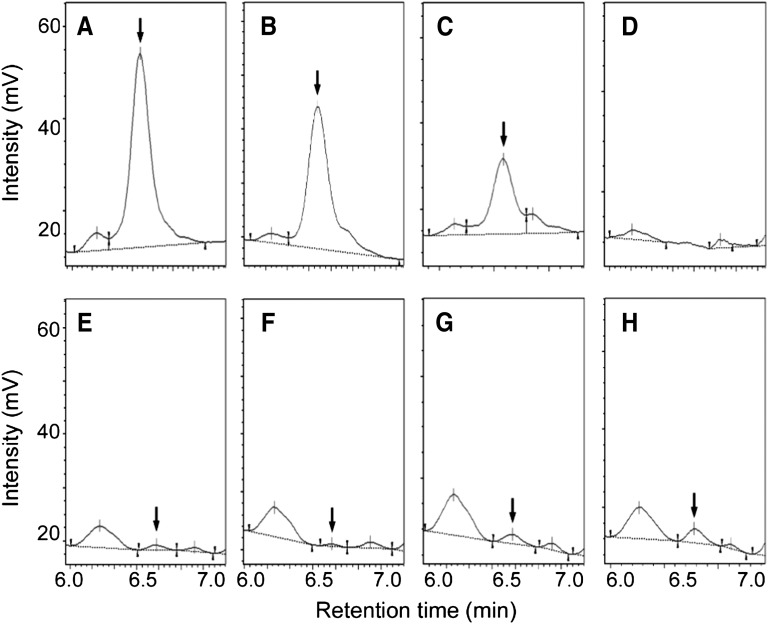

Plasma lyso-Gb3 was detected in 3 of the 47 patients with low α-Gal A activity (6.4%). Figure 2 shows representative high-performance liquid chromatography profiles of lyso-Gb3 in plasma samples from the patients in cases 1, 2, and 3, the elder sister of the patient in case 1, and a control participant. The median plasma lyso-Gb3 level in the three patients was 3.1 nM (1.9–128 nM). Their plasma α-Gal A activity was lower than that of the patients without detectable lyso-Gb3 (n=44), 2.2±0.8 nmol/h per milliliter (range, 1.3–2.9 nmol/h per milliliter) versus 3.4±0.6 nmol/h per milliliter (range, 1.9–4.0 nmol/h per milliliter), respectively (P<0.02).

Figure 2.

High-performance liquid chromatography profiles of OPA-derivatized lyso-Gb3 extracted from human plasma. The peak identified as OPA-derivatized lyso-Gb3 is indicated by the arrow. (A) Case 1 (p.Y173X hemizygote, 128 nM lyso-Gb3); (B) 100 nM authentic lyso-Gb3 in normal plasma; (C) 50 nM authentic lyso-Gb3 in normal plasma; (D) normal plasma; (E) case 2 (p.E66Q hemizygote, 3.1 nM lyso-Gb3); (F) case 3 (p.E66Q hemizygote, 1.9 nM lyso-Gb3); (G) case 1’s elder sister (p.Y173X heterozygote, 6.9 nM lyso-Gb3); and (H) 10 nM authentic lyso-Gb3 in normal plasma. OPA, O-phthaldialdehyde; lyso-Gb3, globotriaosylsphingosine.

Case Presentation

A 28-year-old man had suffered from hypohidrosis from early childhood. Acroparesthesia was not detected (Table 1). At age 27 years, he suffered from loss of appetite, headache, leg edema, and vertigo. One month later, severe kidney dysfunction, hypertension, anemia, and atrophy of the kidneys were detected at the first medical examination. The diagnosis was stage 5 CKD due to an unknown cause; he was unfamiliar with FD. He started dialysis immediately. One month later, he developed restless legs syndrome, which can be associated with FD (19,20) and insomnia. His plasma α-Gal A activity was 1.3 nmol/h per milliliter, and lyso-Gb3 was 128 nM. In his first genetic counseling session, he stated that he hoped the cause of his sickness could be determined.

Table 1.

Characteristics of three patients with a positive result in the lyso-Gb3 screen

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 28 | 49 | 74 |

| Cause of CKD | Fabry disease | Focal glomerulosclerosis | Chronic GN |

| Age dialysis started (yr) | 27 | 30 | 58 |

| Plasma α-Gal A (nmol/h per milliliter) | 1.3 | 2.9 | 2.3 |

| Plasma lyso-Gb3 (nM) | 128 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| GLA mutation | |||

| Nucleotide change | c.519C>A | c.196G>C | c.196G>C |

| Amino acid change | p.Y173X | p.E66Q | p.E66Q |

| MSSI | 32 | 30 | 30 |

| ERT started | Yes | No | No |

The cause of CKD in case 1 was considered unknown before study participation. GLA, α-galactosidase A gene; MSSI, Mainz Severity Score Index; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy.

The physical examination disclosed abdominal angiokeratoma and bilateral lower limb lympho-edema. Genetic testing showed a nonsense mutation in GLA (c.519C>A, p.Y173X) (21). The Mainz Severity Score Index (MSSI) score (22) was 32. Thus, his CKD was caused by FD. He started ERT within 5 months after the primary screening, and his plasma lyso-Gb3 level was 20 nM after 2 months of treatment. The patient’s parents were divorced, and he had lived with his father. He was not in contact with his mother, who was suspected to be a heterozygote of the GLA mutation.

The patient’s elder sister, who did not present any clinical signs of FD, requested genetic counseling and testing. Her plasma α-Gal A activity and lyso-Gb3 were 4.5 nmol/h per milliliter and 6.9 nM, respectively. She had the same GLA mutation as the patient in case 1, as a heterozygote. All of the sister’s four children had the same GLA mutation, and the three youngest showed only mild heat intolerance as a sign of FD. The children’s characteristics were as follows: 10-year-old female, 5.2 nmol/h per milliliter plasma α-Gal A activity, and no detectable lyso-Gb3; 8-year-old female, 1.3 nmol/h per milliliter plasma α-Gal A activity, and 8 nM lyso-Gb3; 4-year-old male, 0.1 nmol/h per milliliter plasma α-Gal A activity, and 83 nM lyso-Gb3; 2-year-old male, 0.0 nmol/h per milliliter plasma α-Gal A activity, and 140 nM lyso-Gb3.

Verification of Lyso-Gb3 Accuracy

Although this study aimed to avoid excess genetic testing, to determine whether the lyso-Gb3 screen captured all cases of FD in the study population, it was necessary to perform genetic testing on patients who had tested positive in the α-Gal A activity screen, but negative in the lyso-Gb3 screen. Forty-four of our original patients met this criterion.

The genetic testing was performed between February 1, 2012 and July 31, 2012. Of the original 44 patients, 9 had died, 1 could not provide informed consent due to dementia, and 1 did not consent to participate. Thus, we performed genetic testing for 33 of the original 44 patients. In 26 patients, there was no mutation in GLA. Seven had a missense mutation in GLA (c.196G>C, p.E66Q) (Table 2) that occurs at an unexpectedly high frequency in Japanese and Korean patients screened for FD. It is not a pathogenic mutation, but a functional polymorphism (23,24).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 7 patients with GLA mutation among 33 patients with positive results in the α-Gal A activity but negative findings in the lyso-Gb3 screen

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 76 | 80 | 75 | 76 | 58 | 62 | 83 |

| Cause of CKD | IgA GN | Chronic GN | Chronic GN | Bilateral ureteral cancer | DM | Chronic GN | NS |

| Age dialysis started (yr) | 52 | 56 | 73 | 71 | 53 | 62 | 79 |

| Plasma α-Gal A (nmol/h per milliliter) | 2.9 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| GLA mutation | |||||||

| Nucleotide change | c.196G>C | c.196G>C | c.196G>C | c.196G >C | c.196G>C | c.196G>C | c.196G>C |

| Amino acid change | p.E66Q | p.E66Q | p.E66Q | p.E66Q | p.E66Q | p.E66Q | p.E66Q |

| MSSI | 18 | 36 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 32 | 26 |

| ERT started | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

GLA, α-galactosidase A gene; α-Gal A, α-galactosidase A; lyso-Gb3, globotriaosylsphingosine; IgA GN, IgA glomerulonephropathy; DM, diabetes mellitus; NS, nephrosclerosis; MSSI, Mainz Severity Score Index; ERT, enzyme replacement therapy.

Including the 3 patients who were positive for lyso-Gb3, we performed genetic testing for a total of 36 male dialysis patients with low α-Gal A activity. Among them, we found one patient whose FD had not been diagnosed previously (case 1; see Table 3 for summary). Thus, the plasma lyso-Gb3 screen identified FD with high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (94.3%).

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of plasma lyso-Gb3 screening for FD

| FD (+) | FD (−) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyso-Gb3 (+) | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Lyso-Gb3 (−) | 0 | 33 | 33 |

| Total | 1 | 35 | 36 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 100 | ||

| Specificity (%) | 94.3 |

In total, we performed α-galactosidase A gene analysis for 36 male dialysis patients with low α-galactosidase A activity. We found one FD (+) patient with class 1 mutation (p.Yl73X) and 35 FD (−) patients consisting of 9 FD (−) patients with class 2 mutation (p.E66Q) and 26 FD (−) patients without a GLA mutation. The sensitivity was calculated by dividing the number of lyso-Gb3 (+) patients by the total number of total FD (+) patients. The specificity was calculated by dividing the number of lyso-Gb3 (−) patients by the number of total FD (−) patients. Lyso-Gb3, globotriaosylsphingosine; FD, Fabry disease; GLA, α-galactosidase A gene.

Discussion

This is the first report on the screening of dialysis patients for FD by measuring plasma lyso-Gb3. Our findings showed that of 1453 male dialysis patients, this method identified 1 new case of FD, and 2 cases with functional GLA mutation; thus, the prevalence of FD in male dialysis patients was 0.07%. The patient with FD had a nonsense mutation (p.Y173X), and the other two had a nonpathogenic missense mutation (p.E66Q). All patients with detectable plasma lyso-Gb3 had a GLA mutation. Finally, 33 patients with positive screening results for α-Gal A activity but negative results for lyso-Gb3 had a normal GLA gene or carried the functional polymorphism p.E66Q. FD was identified exclusively in a patient with detectable plasma lyso-Gb3.

Published reports on male dialysis patients screened for FD (summarized in Table 4) show that when 0.5% or fewer of the patients were given genetic testing, 100% were positive for FD (2,4,6,7,9). In those in which ≥4% of the patients were tested, 33% or fewer had diagnosable FD (8,10,11). These results show that α-Gal A activity alone does not permit the selective identification of patients who are at high risk for FD. Furthermore, because additional sampling and tests can be upsetting to the patient, we strongly feel that reducing the number of false positives is important for patients’ peace of mind. In published studies, all but one (3) had a very high rate of re-sampling in cases that were identified as false positives: 66.7% (6), 90.9% (7), 92.5% (5), and 93.1% (9). If the genetic test from which the GLA mutation was not detected was defined as the unnecessary genetic tests, similarly, unnecessary genetic tests were carried out in a high percentage of patients in some studies: 60.0% (5), 66.7% (8), 86.7% (11), and 96.0% (10). Unnecessary genetic tests of some studies were 0% (2–4,6,7,9). To avoid false negative results, the screening cutoff α-Gal A level, the percentage of the control mean or cohort mean was recently set at approximately ≥50% (7–11). Secondary screening was needed to realize 0 unnecessary genetic tests (7,9). Finally, to educate patients and help them manage stress, we strongly feel that genetic counseling should be given before genetic testing, but only to patients who are strongly suspected of having or carrying a mutation for a genetic disease.

Table 4.

Reports on FD screening of male dialysis patients

| Authors, Year | First Sampling | Re-Sampling | Plasma Gb3, Lyso-Gb3 | Positive before Genetic Testing | Positive by Genetic Testing | New Discovery Frequency | UnnecessaryRe-Sampling (%) | Unnecessary Genetic Testing (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Cutoffα-GalA Levela | α-Gal A | α-Gal A | |||||||

| Utsumi et al, 2000 (2) | 5.0 | Plasma, 2/440 (0.5) | 2/440 (0.5) | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/440 (0.5) | 0/2 (0.0) | |||

| Nakao et al., 2003 (3) | 29.8 | Plasma, 6/514 (1.2) | WBC, 6/6 (100.0) | Gb3, 6/6 (100.0) | 6/514 (1.2) | 6/6 (100.0) | 6/514 (1.2) | 0/6 (0.0) | |

| Linthorst et al., 2003 (4) | 9.6 | Whole blood, 1/508 (0.2) | 1/508 (0.2) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/508 (0.2) | 0/1 (0.0) | |||

| Kotanko et al., 2004 (5) | 35.0 | DBS, 53/1516 (3.6) | WBC, 10/53 (18.9) | 10/1516 (0.7) | 4/10 (40.0) | 4/1516 (0.3) | 49/53 (92.5) | 6/10 (60.0) | |

| Ichinose et al., 2005 (6) | 15.4 | Plasma, 3/450 (0.7) | WBC, 1/3 (33.3) | 1/450 (0.2) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/450 (0.2) | 2/3 (66.7) | 0/1 (0.0) | |

| Tanaka et al., 2005 (7) | 58.2 | Plasma, 11/398 (2.8) | WBC, 1/11 (9.1) | 1/398 (0.3) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/389 (0.3) | 10/11 (90.9) | 0/1 (0.0) | |

| Bekri et al., 2005 (8) | 55.0 | WBC, 3/59 (5.1) | 3/59 (5.1) | 1/3 (33.3) | 1/59 (1.7) | 2/3 (66.7) | |||

| Merta et al., 2007 (9) | 62.6 | DBS, 58/1521 (3.8) | Plasma, WBC, 4/58 (6.9) | 4/1521 (0.3) | 4/4 (100.0) | 4/1521 (0.3) | 54/58 (93.1) | 0/4 (0.0) | |

| Fujii et al., 2009 (10) | 66.0 | DBS, 25/625 (4.0) | 25/625 (4.0) | 1/25 (4.0) | 1/625 (0.2) | 24/25 (96.0) | |||

| Gaspar et al., 2010 (11) | 48.0 | DBS, 30/543 (5.5) | 30/543 (5.5) | 4/30 (13.3) | 4/543 (0.7) | 26/30 (86.7) | |||

| This study | 54.1 | Plasma, 47/1453 (3.2) | Lyso-Gb3, 3/47 (6.4) | 3/1453 (0.2) | 3/3 (100.0) | 3/1453 (0.2) | 0/3 (0.0) | ||

Data are presented as sample (% positive), unless otherwise indicated. FD, Fabry disease; α-Gal A, α-galactosidase A; Gb3, globotriaosylceramide; lyso-Gb3, globotriaosylsphingosine; WBC, white blood cell; DBS, dried blood spot.

Data are presented as the % of control mean or cohort mean.

In this study, a GLA mutation was found in all of the patients with detectable plasma lyso-Gb3 levels. Although our case sample was small, our findings indicate that plasma lyso-Gb3 is an effective secondary screening target for refining and verifying positive results in an α-Gal A activity screen. In support of the need for a secondary screen, Andrade et al. (25) reported false negative results in an α-Gal A activity screen. Secondary screening for plasma lyso-Gb3 levels may solve this problem.

Two classes of GLA mutations are recognized according to their pathogenicity (26). Class 1 mutations have a high probability of causing disease. Class 2 mutations are nonpathogenic polymorphisms and include five missense changes (p.E66Q, p.S102L, p.S126G, p.D313Y, p.F396Y) (23,27). Therefore, the two patients in this study with detectable lyso-Gb3 levels and the p.E66Q mutation (cases 2 and 3 in Table 1) have not begun ERT.

p.E66Q is a class 2 mutation that retains a high residual enzyme activity (17). Therefore, plasma lyso-Gb3 could be difficult to detect in patients with this mutation. However, we detected plasma lyso-Gb3 in two different families with the p.E66Q mutation, suggesting that detectable plasma lyso-Gb3 may directly reflect the existence of a GLA mutation, a point that is very important to verify.

Among our patients testing positive in the α-Gal A activity screen but negative for lyso-Gb3, the only GLA mutation detected was p.E66Q. The fact that the lyso-Gb3 screen missed these individuals may indicate that some patients with class 2 mutations produce low levels or no lyso-Gb3. Although there is little downside to lyso-Gb3 being undetectable in some patients with class 2 mutations (ERT is not currently indicated for these patients), it is important not to overlook class 1 mutations. Further investigations are necessary to clarify whether all class 1 mutations result in the production of lyso-Gb3.

Of seven reports on the FD screening of Japanese male dialysis patients, including the two most recent (2,3,6,7,10,28,29), the p.E66Q mutation was found in four studies (3,10,28,29). Thus, the p.E66Q mutation in this population is frequently detected. If we exclude the FD patients with p.E66Q in the previous reports, the prevalence of FD is 0% (10,28,29), 0.2% (6), 0.3% (7), 0.5% (2), and 1.0% (3). The low prevalence of FD in this study was concerned with excluding a patient with FD from study population or a study limitation that not all patients were genotyped, leaving open the possibility that there were some cases of FD missed.

In the pedigree analysis for the family of the patient in case 1, the children who were hemizygotes for the class 1 FD mutation and the adult heterozygote all had detectable lyso-Gb3 concentrations. Plasma lyso-Gb3 may also be a promising screening target for adult heterozygotes. By contrast, lyso-Gb3 was not detected in the 10-year-old asymptomatic heterozygote, probably because lyso-Gb3 accumulates more slowly in heterozygotes than in hemizygotes (12). Rombach et al. (14) reported that some very young asymptomatic children who were heterozygous for a class 1 FD mutation showed normal lyso-Gb3 levels. Thus, plasma lyso-Gb3 levels vary with the mutation and among individuals. Therefore, the detection of lyso-Gb3 may become a useful marker for even nonpathologic GLA mutations, if the detection sensitivity of the test can be increased.

Plasma lyso-Gb3 is a promising screening tool that was effective for identifying candidates for genetic counseling and genetic testing, and for uncovering unrecognized FD among male dialysis patients.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Utako Seino for technical assistance. We are indebted to the patients, nurses, medical engineers, and physicians who supported this study. The participating centers and physicians were as follows: Yoshiaki Miura (Miura Medical Clinic), Yutaka Osawa (Niigata Rinko Hospital), Yutaka Koda (Koda Medical Clinic), Masaaki Nagai (Aoyagi Clinic), Kensuke Suzuki and Noriaki Kobayashi (Kitamachi Clinic), Isei Ei (Santo Daini Clinic), Kentaro Omori and Tsukasa Omori (Omori Clinic), Katsuya Kimura (Gosen Rokushima Clinic), Takayuki Sato (Nanbugo Kosei Hospital), Nobuyuki Sakurai (Murakami Memorial Hospital), Hajime Yamazaki (Nagaoka Red Cross Hospital), Shigemi Kameda (Joetsu General Hospital), Ikuo Aoike (Koyo Medical Clinic), Takashi Watanabe (Watanabe Medical Clinic), Akira Kamimura and Yoichi Iwafuchi (Sanjou General Hospital), Syogo Yada (Kido Hospital), Hirokazu Fujikawa (Maihira Clinic), Kaoru Oya (Kaetsu Hospital), Masanori Katagiri (Katagiri Clinic), Gen Nakamura and Yoshio Morioka (Sado General Hospital), Tsukasa Nakamaru (Niigata Prefectural Koide Hospital), Yukihiro Morita (Morita Medical Clinic), Ryuji Aoyagi (Tachikawa General Hospital), Shin Goto, Noriaki Iino, and Kazuko Kawamura (Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital), Hitoshi Igarashi (Niigata Prefectural Sakamachi Hospital), Noriyuki Homma (Niigata Prefectural Shibata Hospital), Taiji Sasagawa (Niigata Prefectural Central Hospital), Yasushi Suzuki (Saiseikai Niigata Daini Hospital), Asa Ogawa (Keinan General Hospital), and Michihiro Hosojima and Yuichi Sakamaki (Ojiya General Hospital).

This work was supported by a grant from the Japanese Association of Dialysis Physicians to H.M.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Brady RO, Gal AE, Bradley RM, Martensson E, Warshaw AL, Laster L: Enzymatic defect in Fabry’s disease. Ceramidetrihexosidase deficiency. N Engl J Med 276: 1163–1167, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Utsumi K, Kase R, Takata T, Sakuraba H, Matsui N, Saito H, Nakumura T, Kawabe M, Iino Y, Katayama Y: Fabry disease in patients receiving maintenance dialysis. Clin Exp Nephrol 4: 49–51, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakao S, Kodama C, Takenaka T, Tanaka A, Yasumoto Y, Yoshida A, Kanzaki T, Enriquez AL, Eng CM, Tanaka H, Tei C, Desnick RJ: Fabry disease: Detection of undiagnosed hemodialysis patients and identification of a “renal variant” phenotype. Kidney Int 64: 801–807, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linthorst GE, Hollak CE, Korevaar JC, Van Manen JG, Aerts JM, Boeschoten EW: α-Galactosidase A deficiency in Dutch patients on dialysis: A critical appraisal of screening for Fabry disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1581–1584, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotanko P, Kramar R, Devrnja D, Paschke E, Voigtländer T, Auinger M, Pagliardini S, Spada M, Demmelbauer K, Lorenz M, Hauser AC, Kofler HJ, Lhotta K, Neyer U, Pronai W, Wallner M, Wieser C, Wiesholzer M, Zodl H, Födinger M, Sunder-Plassmann G: Results of a nationwide screening for Anderson-Fabry disease among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1323–1329, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichinose M, Nakayama M, Ohashi T, Utsunomiya Y, Kobayashi M, Eto Y: Significance of screening for Fabry disease among male dialysis patients. Clin Exp Nephrol 9: 228–232, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka M, Ohashi T, Kobayashi M, Eto Y, Miyamura N, Nishida K, Araki E, Itoh K, Matsushita K, Hara M, Kuwahara K, Nakano T, Yasumoto N, Nonoguchi H, Tomita K: Identification of Fabry’s disease by the screening of α-galactosidase A activity in male and female hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 64: 281–287, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekri S, Enica A, Ghafari T, Plaza G, Champenois I, Choukroun G, Unwin R, Jaeger P: Fabry disease in patients with end-stage renal failure: The potential benefits of screening. Nephron Clin Pract 101: c33–c38, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merta M, Reiterova J, Ledvinova J, Poupetová H, Dobrovolny R, Rysavá R, Maixnerová D, Bultas J, Motán J, Slivkova J, Sobotova D, Smrzova J, Tesar V: A nationwide blood spot screening study for Fabry disease in the Czech Republic haemodialysis patient population. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 179–186, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujii H, Kono K, Goto S, Onishi T, Kawai H, Hirata K, Hattori K, Nakamura K, Endo F, Fukagawa M: Prevalence and cardiovascular features of Japanese hemodialysis patients with Fabry disease. Am J Nephrol 30: 527–535, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaspar P, Herrera J, Rodrigues D, Cerezo S, Delgado R, Andrade CF, Forascepi R, Macias J, del Pino MD, Prados MD, de Alegria PR, Torres G, Vidau P, Sá-Miranda MC: Frequency of Fabry disease in male and female haemodialysis patients in Spain. BMC Med Genet 11: 19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aerts JM, Groener JE, Kuiper S, Donker-Koopman WE, Strijland A, Ottenhoff R, van Roomen C, Mirzaian M, Wijburg FA, Linthorst GE, Vedder AC, Rombach SM, Cox-Brinkman J, Somerharju P, Boot RG, Hollak CE, Brady RO, Poorthuis BJ: Elevated globotriaosylsphingosine is a hallmark of Fabry disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 2812–2817, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Togawa T, Kodama T, Suzuki T, Sugawara K, Tsukimura T, Ohashi T, Ishige N, Suzuki K, Kitagawa T, Sakuraba H: Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine as a biomarker of Fabry disease. Mol Genet Metab 100: 257–261, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rombach SM, Dekker N, Bouwman MG, Linthorst GE, Zwinderman AH, Wijburg FA, Kuiper S, Vd Bergh Weerman MA, Groener JE, Poorthuis BJ, Hollak CE, Aerts JM: Plasma globotriaosylsphingosine: Diagnostic value and relation to clinical manifestations of Fabry disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1802: 741–748, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Breemen MJ, Rombach SM, Dekker N, Poorthuis BJ, Linthorst GE, Zwinderman AH, Breunig F, Wanner C, Aerts JM, Hollak CE: Reduction of elevated plasma globotriaosylsphingosine in patients with classic Fabry disease following enzyme replacement therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 70–76, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desnick RJ, Allen KY, Desnick SJ, Raman MK, Bernlohr RW, Krivit W: Fabry’s disease: Enzymatic diagnosis of hemizygotes and heterozygotes. Alpha-galactosidase activities in plasma, serum, urine, and leukocytes. J Lab Clin Med 81: 157–171, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimotori M, Maruyama H, Nakamura G, Suyama T, Sakamoto F, Itoh M, Miyabayashi S, Ohnishi T, Sakai N, Wataya-Kaneda M, Kubota M, Takahashi T, Mori T, Tamura K, Kageyama S, Shio N, Maeba T, Yahagi H, Tanaka M, Oka M, Sugiyama H, Sugawara T, Mori N, Tsukamoto H, Tamagaki K, Tanda S, Suzuki Y, Shinonaga C, Miyazaki J, Ishii S, Gejyo F: Novel mutations of the GLA gene in Japanese patients with Fabry disease and their functional characterization by active site specific chaperone. Hum Mutat 29: 331, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Japanese Association of Medical Sciences: Guidelines for Genetic Tests and Diagnoses in Medical Practice, 2011. Available at: http://jams.med.or.jp/. Accessed February 18, 2011

- 19.Domínguez RO, Michref A, Tanus E, Amartino H: [Restless legs syndrome in Fabry disease: Clinical feature associated to neuropathic pain is overlooked]. Rev Neurol 45: 474–478, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mucsi I, Molnar MZ, Ambrus C, Szeifert L, Kovacs AZ, Zoller R, Barótfi S, Remport A, Novak M: Restless legs syndrome, insomnia and quality of life in patients on maintenance dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 571–577, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shabbeer J, Yasuda M, Benson SD, Desnick RJ: Fabry disease: Identification of 50 novel alpha-galactosidase A mutations causing the classic phenotype and three-dimensional structural analysis of 29 missense mutations. Hum Genomics 2: 297–309, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whybra C, Kampmann C, Krummenauer F, Ries M, Mengel E, Miebach E, Baehner F, Kim K, Bajbouj M, Schwarting A, Gal A, Beck M: The Mainz Severity Score Index: A new instrument for quantifying the Anderson-Fabry disease phenotype, and the response of patients to enzyme replacement therapy. Clin Genet 65: 299–307, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee BH, Heo SH, Kim GH, Park JY, Kim WS, Kang DH, Choe KH, Kim WH, Yang SH, Yoo HW: Mutations of the GLA gene in Korean patients with Fabry disease and frequency of the E66Q allele as a functional variant in Korean newborns. J Hum Genet 55: 512–517, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Togawa T, Tsukimura T, Kodama T, Tanaka T, Kawashima I, Saito S, Ohno K, Fukushige T, Kanekura T, Satomura A, Kang DH, Lee BH, Yoo HW, Doi K, Noiri E, Sakuraba H: Fabry disease: Biochemical, pathological and structural studies of the α-galactosidase A with E66Q amino acid substitution. Mol Genet Metab 105: 615–620, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrade J, Waters PJ, Singh RS, Levin A, Toh BC, Vallance HD, Sirrs S: Screening for Fabry disease in patients with chronic kidney disease: Limitations of plasma α-galactosidase assay as a screening test. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 139–145, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gal A, Hughes DA, Winchester B: Toward a consensus in the laboratory diagnostics of Fabry disease - recommendations of a European expert group. J Inherit Metab Dis 34: 509–514, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gal A: Molecular genetics of Fabry disease and genotype–phenotype correlation. In: Fabry Disease, edited by Elstein D, Altarescu G, Beck M, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Springer Science + Business Media B.V., 2010, pp 3–19 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishino T, Obata Y, Furusu A, Hirose M, Shinzato K, Hattori K, Nakamura K, Matsumoto T, Endo F, Kohno S: Identification of a novel mutation and prevalence study for Fabry disease in Japanese dialysis patients. Ren Fail 34: 566–570, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kikumoto Y, Sugiyama H, Morinaga H, Inoue T, Takiue K, Kitagawa M, Saito D, Takatori Y, Kinomura M, Kitamura S, Akagi S, Sada K, Nakao K, Maeshima Y, Kitayama H, Makino H: The frequency of Fabry disease with the E66Q variant in the α-galactosidase A gene in Japanese dialysis patients: A case report and a literature review. Clin Nephrol 78: 224–229, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]