SUMMARY

The attachment of the SUMO modifier to proteins controls cellular signaling pathways through noncovalent binding to SUMO-interaction motifs (SIMs). Canonical SIMs contain a core of hydrophobic residues that bind to a hydrophobic pocket on SUMO. Negatively charged residues of SIMs frequently contribute to binding by interacting with a basic surface on SUMO. Here we define acetylation within this basic interface as a central mechanism for the control of SUMO-mediated interactions. The acetyl-mediated neutralization of basic charges on SUMO prevents binding to SIMs in PML, Daxx, and PIAS family members but does not affect the interaction between RanBP2 and SUMO. Acetylation is controlled by HDACs and attenuates SUMO- and PIAS-mediated gene silencing. Moreover, it affects the assembly of PML nuclear bodies and restrains the recruitment of the corepressor Daxx to these structures. This acetyl-dependent switch thus expands the regulatory repertoire of SUMO signaling and determines the selectivity and dynamics of SUMO-SIM interactions.

INTRODUCTION

The reversible posttranslational modification of proteins through acetylation, phosphorylation, or ubiquitylation governs the plasticity of protein interaction networks (Deribe et al., 2010). A key regulatory principle is the recognition of these modifications by specific interaction domains (Seet et al., 2006). The conjugation of the ubiquitin-related SUMO protein also modulates specific protein-protein interactions and thereby controls various cellular signaling processes, including DNA repair pathways, ribosome biogenesis, and gene expression programs (Gareau and Lima, 2010; Wilkinson and Henley, 2010). In human cells, SUMO1 and the closely related SUMO2 and SUMO3 function as modifiers. All are covalently attached to lysine residues of target proteins in a pathway that requires a dimeric E1-conjugating enzyme (Aos1/Uba2) and the E2-conjugating enzyme Ubc9. E3 SUMO ligases, such as the nucleoporin RanBP2 or members of the PIAS family, act as specificity factors and enhancers in the modification process (Palvimo, 2007; Schmidt and Muller, 2003). Sumoylation is reversed by SUMO-specific isopeptidases of the SENP family that catalyze the removal of SUMO from target proteins (Hay, 2007; Mukhopadhyay and Dasso, 2007).

Attachment of SUMO typically earmarks a protein for the recognition by a binding partner that contains a SUMO-interaction motif (SIM) (Kerscher, 2007; van Wijk et al., 2011). This promotes distinct protein-protein interactions and in some cases affects the spatial distribution of proteins. Key examples are the targeting of sumoylated RanGAP1 to the nucleoporin RanBP2 or the SUMO-SIM-dependent assembly of PML nuclear bodies (NBs) (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007; Mahajan et al., 1998; Matunis et al., 1998, 2006; Mukhopadhyay and Matunis, 2011). Another well-defined SUMO-regulated process is the repression of gene expression, which can be directly mediated by the recruitment of SIM-containing transcriptional coregulators to sumoylated transcription factors (Ouyang et al., 2009; Stielow et al., 2008). There is also accumulating evidence that transrepression of proinflammatory genes by sumoylated nuclear receptors is mediated by SIM-containing corepressors (Huang et al., 2011; Pascual et al., 2005; Venteclef et al., 2010). Canonical SIMs are characterized by a short stretch of hydrophobic residues for which a loosely conserved consensus sequence ([V/I]-x-[V/I]-[V/I] or [V/I]-[V/I]-x-[V/I]) has been defined (Kerscher, 2007; Praefcke et al., 2012; van Wijk et al., 2011). When bound to SUMO, the SIM interacts with a hydrophobic pocket on the SUMO surface and forms a β strand that aligns in parallel or anti-parallel orientation to the β2 strand of SUMO. In many cases, acidic residues juxtapose the hydrophobic core of SIMs and enhance the binding affinity by providing electrostatic interactions with a basic interface on SUMO, which includes K37, K39, and K46 in SUMO1 and the corresponding K33, K35, and K42 in SUMO2.

Our recent work unraveled an interconnection of posttranslational modifications for the dynamic control of SUMO-SIM interactions. We found that in a subset of SIM-containing proteins serine or threonine residues that juxtapose the hydrophobic core are phosphorylated by the kinase CK2 (Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). The additional negative charge that is provided by phosphate groups enhances the binding of free SUMO and SUMO conjugates through electrostatic interactions with a conserved lysine residue in the basic interface of SUMO (K39 in SUMO1 and K35 in SUMO2) (Chang et al., 2011; Hecker et al., 2006; Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). We initially defined phosphoSIMs in the PML protein and PIAS family members, and more recently Chang and coworkers characterized a CK2-controlled phosphoSIM in the PML-associated apoptotic regulator Daxx (Chang et al., 2011; Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). These data thus revealed an intricate crosstalk between the ubiquitin-like SUMO system and signaling by the protein kinase CK2.

Here we define site-specific acetylation of SUMO paralogs as a regulatory principle in the control of SUMO-SIM interactions. Using biochemical and cell-biological approaches, we demonstrate that acetylation of SUMO1 at lysine 37 or SUMO2 at lysine 33 selectively modulates its binding to SIMs. K33/K37 acetylation abolishes binding to PML, Daxx, and PIAS family members, thereby affecting the dynamics of PML NBs and SUMO-dependent gene silencing.

RESULTS

Acetylation of SUMO Paralogs Affects Specific SUMO-SIM Interactions

To get insight into signaling by SUMO and the control of SUMO-SIM interactions, we searched for posttranslational modifications on SUMO paralogs using mass spectrometry. MS/MS analysis of immunoprecipitates from cells expressing Flag-tagged SUMO2 revealed acetylation of free SUMO2 at lysine K33 (see Figure S1A online). Acetylation of this residue was also found on endogenous SUMO2/3 conjugates, indicating that it occurs under physiological conditions (Figure S1B). Consistent with this finding, we have recently demonstrated acetylation of the corresponding residue K37 in SUMO1 using MS/MS and a K37 acetyl-specific antibody (Cheema et al., 2010).

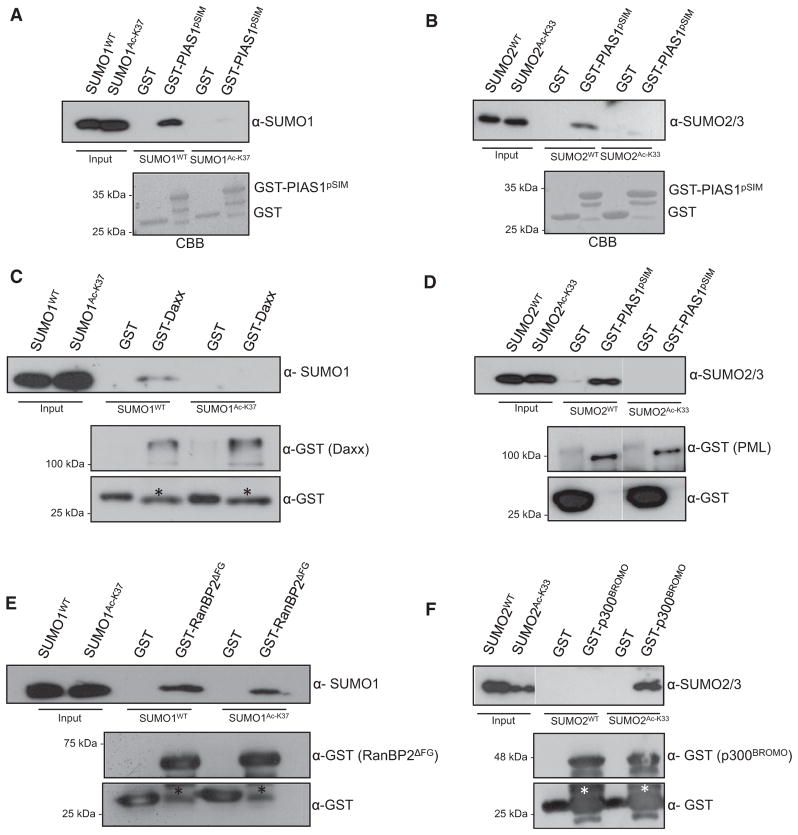

Importantly, we and others have previously shown that the positive charges of SUMO1 at lysine 37 and SUMO2 at lysine 33 are required for their interaction with SIMs, including the SIM module of PIAS family members (Rosendorff et al., 2006; Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). To test whether K37/K33 acetylation of SUMO paralogs affects SIM interactions, we generated K37-acetylated SUMO1 and K33-acetylated SUMO2 using a recently developed method that allows the site-specific acetylation of recombinant proteins in bacteria (Neumann et al., 2009) (Figures S2A and S2B). The system uses a synthetially evolved acetyl-lysyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA(CUA) pair to produce homogenously acetylated proteins. Site-specific acetylation of recombinant SUMO1 at lysine 37 was validated by immunoblotting with the K37 acetyl-specific antibody (Figure S2C), while acetylation of SUMO2 was confirmed with a panacetyllysine antibody and K33-specific modification was demonstrated by MS/MS (Figures S2D and S2E). We next compared the binding of SUMO1Ac-K37 or SUMO2Ac-K33 and the respective unmodified proteins to the SIM of PIAS1, a well-characterized archetypical SUMO-binding module that binds SUMO in a parallel orientation (Figures 1A and 1B). Consistent with our previous work, unmodified SUMO1 or SUMO2 strongly associates with the SIM fused to GST (Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). By contrast, the K37-acetylated form of SUMO1 and the K33-acetylated SUMO2 failed to bind to this region (Figures 1A and 1B). To expand on this finding, we compared binding of unmodified and acetylated SUMO to full-length PIAS1 (Figure S3A). A robust binding of unmodified SUMO2 to PIAS 1 was observed, but no interaction was seen for SUMO2Ac-K33, further indicating that acetylation precludes the interaction of SUMO with the SIM region of PIAS. In further support of this idea, preacetylation of recombinant SUMO2 by the acetyltransferase p300 strongly reduced the interaction of SUMO2 with PIAS1 (Figures S3A and S3B). To investigate whether acetylation of SUMO more generally interferes with SIM binding, we tested the interaction of unmodified and K37-acetylated SUMO1 or K33-acetylated SUMO2 to GST-Daxx and GST-PML, which both contain a PIAS1-related phosphoSIM motif and interact with SUMO in a SIM-dependent manner (Chang et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2006; Song et al., 2004, 2005; Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). Similarly to what was observed for PIAS1, wild-type SUMO1 or SUMO2, but not the acetylated forms (SUMO1Ac-K37 or SUMO2Ac-K33), was retained on beads loaded with GST-Daxx or GST-PML (Figures 1C and 1D and Figure S3C). Altogether these biochemical experiments suggest that neutralization of the positive charge at K37 in SUMO1 or K33 in SUMO2 prevents the binding of SUMO paralogs to SIM-containing proteins. This is supported by structural data on the interaction of SUMO with a peptide derived from the SIM region of PIAS2 (KVDVIDLTIESSSDEEEDPPAKR), where a salt bridge between the aspartic acid in position 6 and the side chain of K37 in SUMO1 or K33 in SUMO2 has been observed (Hecker et al., 2006; Namanja et al., 2011; Song et al., 2004, 2005). Notably, however, in the case of RanBP2, which harbors two adjacent antiparallel SIMs in the IR1-M-IR2 region, structural data show that lysine 37 of SUMO1 does not contribute to SUMO-SIM binding via an electrostatic interaction (Namanja et al., 2011; Reverter and Lima, 2005; Song et al., 2004, 2005; Tatham et al., 2005). In this antiparallel orientation, K37 forms a hydrogen bond with either a leucine in SIM1, which resides in the IR1 region, or an isoleucine in SIM2 that is found within the M-IR2 domain. To see whether this antiparallel type of SUMO-SIM interaction is also controlled by K37 acetylation, we monitored binding of SUMO1 and SUMO1Ac-K37 to the RanBP2ΔFG fragment, which contains the IR1-M-IR2 region. Intriguingly, GST-RanBP2ΔFG interacts with acetylated and unmodified SUMO1 to a similar extent, indicating that this interaction is not regulated via acetylation at K37 (Figure 1E). This finding is thus in perfect agreement with the idea that positive charges at K37 are not required for this type of SUMO-SIM interaction.

Figure 1. Acetylation of SUMO Paralogs Regulates SUMO-SIM Interactions.

(A) GST or the phosphomimicking variant of the phosphoSIM module of PIAS1 fused to GST was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with recombinantly expressed wild-type SUMO1 or K37-acetylated SUMO1. After intensive washing, bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by anti-SUMO1 immunoblotting or staining with Coomassie blue.

(B) As in (A), but glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with recombinantly expressed wild-type SUMO2 or K33-acetylated SUMO2. Proteins were visualized by anti-SUMO2 immunoblotting or staining with Coomassie blue.

(C) As in (A), but glutathione-Sepharose beads were loaded with GST or GST-Daxx and incubated with wild-type SUMO1 or K37-acetylated SUMO1. Proteins were visualized by anti-SUMO1 or anti-GST immunoblotting. Asterisks represent a truncated GST-Daxx form that is detected by anti-GST antibodies.

(D) As in (A), but glutathione-Sepharose beads loaded with GST or GST-PML were incubated with wild-type SUMO2 or K33-acetylated SUMO2. Proteins were visualized by anti-SUMO2 or anti-GST immunoblotting.

(E) As in (A), but glutathione-Sepharose beads loaded with GST or GST-RanBP2ΔFG were incubated with wild-type SUMO1 or K37-acetylated SUMO1. Proteins were visualized by anti-SUMO1 or anti-GST immunoblotting. Asterisks represent a truncated GST-RanBP2 ΔFG form that is detected by anti-GST antibodies.

(F) As in (A), but glutathione-Sepharose beads loaded with GST or the bromodomain of p300 (amino acids 1,047–1,157) fused to GST (GST-p300BROMO) were incubated with wild-type SUMO2 or K33-acetylated SUMO2. Proteins were visualized by anti-SUMO2 or anti-GST immunoblotting. Asterisks represent a truncated GST-p300BROMO form that is detected by anti-GST antibodies.

Acetyl-lysine residues of histones and transcription factors are typically recognized by bromodomains (Ruthenburg et al., 2007; Taverna et al., 2007). To determine whether acetyl-lysine residues in SUMO paralogs can be read by this module, the bromodomain of p300 was fused to GST, and GST pull-down assays with unmodified or K37/K33-acetyl SUMO were performed (Figure 1F). Unmodified SUMO paralogs did not associate with the bromodomain. Interestingly, however, K33-acetyl SUMO2, but not K37-acetyl SUMO1 (data not shown), specifically bound to GST-p300Bromo, indicating that K33 acetylation of SUMO2 may mediate the recruitment of bromodomain-containing proteins, such as the coactivator p300. Acetylation of SUMO2 may thus function as a switch that facilitates a dynamic corepressor/coactivator exchange in transcriptional processes.

Acetylation Attenuates SUMO-Mediated Transcriptional Repression

To study acetyl-regulated SIM binding in a cellular context, we used SUMO1 or SUMO2 versions where lysine 37 or 33, respectively, was substituted with glutamine, because in many instances glutamine has been shown to mimic acetyl-lysine residues (Kamieniarz and Schneider, 2009). In directed yeast two-hybrid assays and in vitro GST-pull-down experiments, SUMO1K37Q and SUMO2K33Q recapitulate the failure of acetylated SUMO1/SUMO2 to bind to PIAS family members (Figures S4A–S4D). Importantly, replacement of lysine 37 or 33 with arginine in SUMO1 or SUMO2, respectively, conserves SUMO-SIM interactions, substantiating the view that the positive charge at these positions is critical for SIM binding (Figures S4A–S4D). Notably also, binding of wild-type SUMO2 and SUMO2K33Q to Ubc9, which is not mediated via a SIM, is comparable, indicating that the SUMO2K33Q variant is not generally affected in protein-protein interactions (Figure 2A).

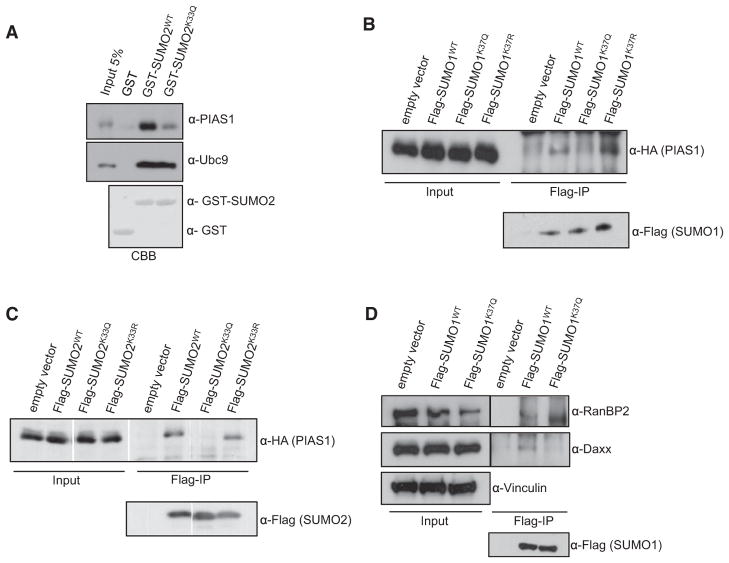

Figure 2. Acetylation of SUMO Paralogs Controls Cellular SUMO-SIM Interactions.

(A) GST, GST-SUMO2WT, or the acetyl-mimicking variant GST-SUMO2K33Q was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads, and beads were incubated with a cell lysate from HeLa cells. After intensive washing, bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and PIAS1 and Ubc9 were detected by immunoblotting.

(B) Nonconjugatable wild-type Flag-SUMO1 or the indicated mutants were coexpressed with HA-tagged versions of PIAS1, immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag beads, and detected by either anti-HA or anti-Flag antibodies.

(C) As in (B), but HA-tagged PIAS1 was expressed with Flag-SUMO2 or the indicated mutants.

(D) Wild-type Flag-SUMO1 or the indicated mutants were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag beads, and association of endogenous RanBP2 or Daxx was detected by immunoblotting with the respective antibodies.

When expressed in HeLa cells, Flag-SUMO1K37Q or Flag-SUMO2K33Q failed to coimmunoprecipitate HA-tagged PIAS1, whereas the respective wild-type proteins as well as mutants with lysine to arginine substitutions robustly bound to PIAS1 (Figures 2B and 2C). Similarly, wild-type Flag-SUMO1, but not Flag-SUMO1K37Q, associates with endogenous Daxx (Figure 2D). Importantly, however, endogenous RanBP2 can be coimmunoprecipitated with both wild-type Flag-SUMO1 and Flag-SUMO1K37Q (Figure 2D). Taken together, these data indicate that in a cellular context the introduction of glutamine residues at K37 or K33 in SUMO paralogs can faithfully mimic the binding characteristics of K37/33 acetyl-SUMO1/2 to SIM regions.

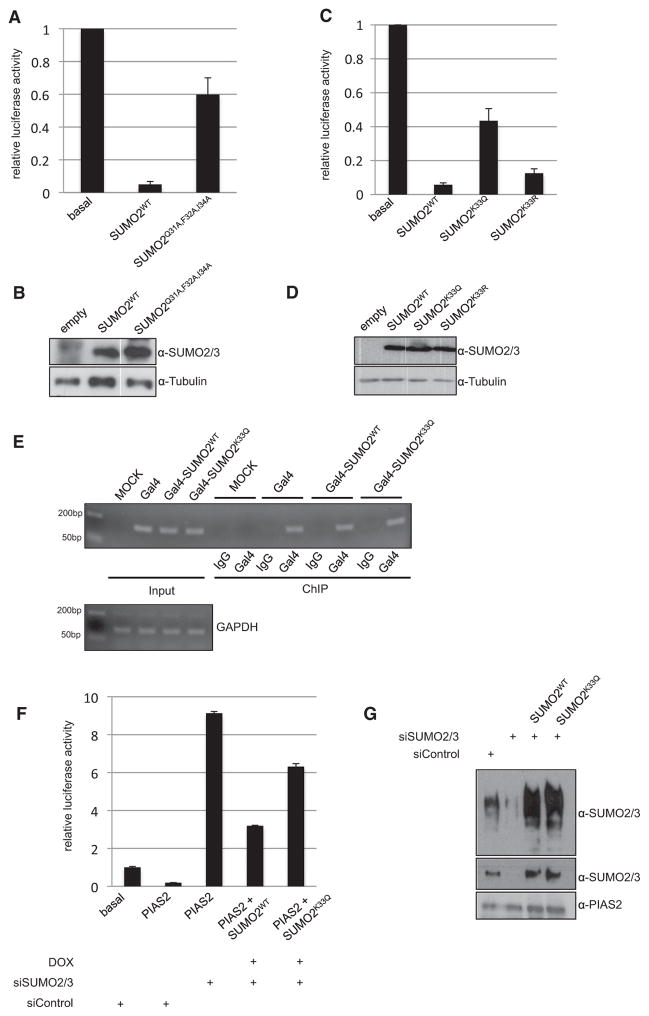

To study the functional consequence of acetylation, we first focused on SUMO-dependent transcriptional repression. When fusing SUMO2 to a Gal4 DNA-binding domain, SUMO-mediated repression can be monitored on luciferase reporter constructs that harbor Gal4-binding sites together with a minimal viral promoter (Rosendorff et al., 2006). By monitoring the repressive potential of wild-type Gal4-SUMO2 and a mutant that has lost the ability to interact with SIM regions (SUMO2Q31A,F32A,I34A), we confirmed that the repression relies on a productive SUMO-SIM interaction (Zhu et al., 2008) (Figures 3A and 3B). Next we compared the transcriptional inhibitory activity of wild-type Gal4-SUMO2, Gal4-SUMO2K33Q, and Gal4-SUMO2K33R. Wild-type Gal4-SUMO2 or Gal4-SUMO2K33R represses Gal4-TK-driven luciferase reporter activity by about 10-fold (Figure 3C). By contrast, when directly tethered to the promoter of the reporter gene, the acetyl-mimicking SUMO2K33Q exhibits a drastically reduced repressive potential and only leads to about 2-fold repression of reporter gene activity. Equal expression and nuclear localization of the respective Gal4-SUMO2 forms were verified by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence (Figure 3D, Figure S5). Moreover, CHIP experiments confirm DNA binding of wild-type GAL4-SUMO2 and GAL4-SUMO2K33Q (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. The Acetylation Restrains SUMO-Mediated Gene Silencing.

(A) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with the Gal4-TK-luciferase reporter plasmid together with plasmids encoding Gal4-SUMO2 fusion proteins as indicated. Values represent the average of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with standard deviation after normalization for the internal control renilla luciferase acitvity. The basal reporter activity was set as 1.

(B) Expression of Gal4-SUMO2 proteins was monitored by western blotting of cell lysates.

(C and D) As in (A) and (B) except that wild-type Gal4-SUMO2 was compared to Gal4-SUMO2K33Q and Gal4-SUMO2K33R.

(E) Binding of the respective Gal4-SUMO2 variants to Gal4-binding sites of the reporter gene was verified by CHIP.

(F) As in (A), except that the activity of the Gal4-PIAS2β was monitored in HeLa cells stably expressing wild-type SUMO2 or the acetyl-mimicking variant SUMO2K33Q under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter. Cells were either transfected with control siRNA or siRNA directed against SUMO2/3. Cells were either uninduced or expression of SUMO2 variants was induced by treatment with doxycycline (DOX). Values represent the average of two independent experiments performed in triplicates (mean ±SD) after normalization for the internal control renilla luciferase activity.

(G) Depletion of endogenous SUMO2 and re-expression of the exogenous proteins was verified by immunoblotting using an anti-SUMO2 antibody. Expression of Gal4-PIAS2 proteins was monitored by western blotting of cell lysates.

We and others have shown that distinct PIAS family members can act as SIM-dependent transrepressors in reporter gene assays (Kotaja et al., 2000, 2002; Rytinki et al., 2009; Schmidt and Muller, 2003; Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). To investigate whether PIAS2-mediated repression is modulated by acetylation of SUMO, we established an siRNA-mediated knockdown/ complementation system. We generated isogenic cell lines that stably express wild-type SUMO1/SUMO2 or the respective acetyl-mimicking variants (SUMO1K37Q or SUMO2K33Q) from a single gene copy under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter. The cells express equal amounts of the respective modifiers at levels that are comparable to the endogenous proteins (Figures S6A and S6B). This cellular system therefore provides a reliable model to study the consequence of acetylation on PIAS2-mediated transrepression in reporter gene assays (Figures 3F and 3G). When compared to basal reporter activity, Gal4-PIAS2 represses a Gal-driven luciferase reporter by about 5-fold. siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous SUMO2/3 (by an siRNA that targets both paralogs) completely abolishes the repressive potential of PIAS2 and even leads to a drastic activation of reporter gene activity. Importantly, re-expression of wild-type SUMO2 restores PIAS2-mediated repression and leads to a 3-fold repression of the reporter gene. By contrast, in the presence of the acetyl-mimicking SUMO2K33Q variant, the repressive activity of Gal4-PIAS2 is largely reduced. In this situation, the reporter activity is only 1.5-fold repressed, indicating that the acetyl-regulated SUMO-SIM interactions control the corepressor function of PIAS.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that acetylation counters SUMO-SIM-dependent transcriptional repression processes.

Acetylation of SUMO Paralogs Affects the Dynamics of PML Nuclear Bodies

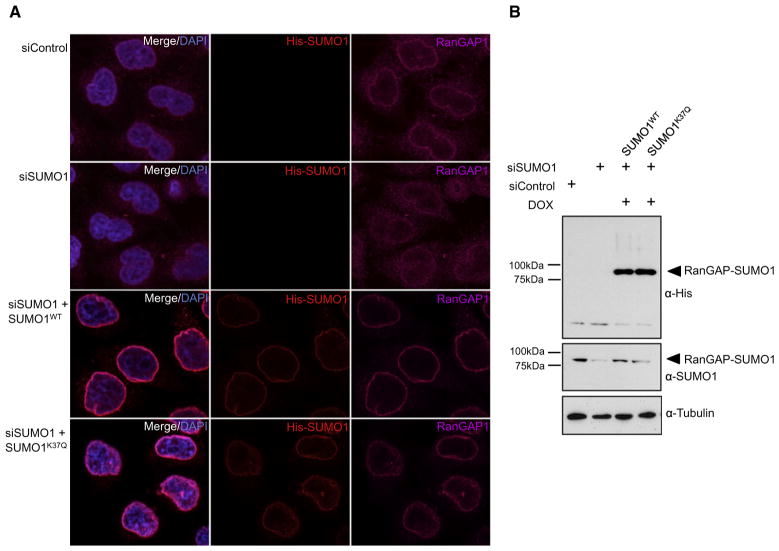

SUMO-SIM-mediated protein-protein interactions can determine the subcellular targeting of proteins. A paradigm is the SUMO-mediated recruitment of RanGAP1 to the nuclear pore, where SUMO-RanGAP1 conjugates are recognized by RanBP2 (Mahajan et al., 1998; Matunis et al., 1998). In a mechanistically similar mode, the apoptotic regulator Daxx is recruited to sumoylated PML, the major SUMO substrate at NBs (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007; Chang et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2006; Matunis et al., 2006; Mukhopadhyay and Matunis, 2011). To determine whether these processes are affected by acetylation of SUMO paralogs, we used the siRNA-mediated knockdown/complementation system described above. RanGAP1 is the predominant SUMO1 target in cells and is targeted to the nuclear envelope via sumoylation (Mahajan et al., 1997; Matunis et al., 1996). Accordingly, indirect immunofluorescence reveals a strong enrichment of RanGAP1 at the nuclear rim, and depletion of SUMO1 reduces the accumulation of RanGAP1 at these sites (Figures 4A and 4B). Residual nuclear rim staining is likely mediated by SUMO2/3, since in the absence of SUMO1 RanGAP1 can be modified by SUMO2/3 (Zhu et al., 2009). Importantly, upon doxycycline-mediated induction of expression, wild-type SUMO1 or SUMO1K37Q is efficiently conjugated to RanGAP1 and mediates its recruitment to the nuclear rim (Figures 4A and 4B). This demonstrates that the acetylation of SUMO1 does not affect targeting of RanGAP1 to RanBP2 at the nuclear pore, which is fully consistent with our biochemical experiments.

Figure 4. K37 Acetylation of SUMO1 Does Not Affect Targeting of RanGAP1 to the Nuclear Pore.

(A) HeLa cells stably expressing wild-type His-SUMO1 or the acetyl-mimicking variant His-SUMO1K37Q under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter were either transfected with control siRNA or siRNA directed against SUMO1. Cells were either uninduced (upper two panels) or expression of His-tagged SUMO1 variants was induced by treatment with doxycycline (lower two panels). Distribution of the respective His-tagged SUMO1 variants (that are resistant to the SUMO1 siRNA) was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-His antibody. The distribution of endogenous RanGAP1 was monitored by an anti-RanGAP1 antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

(B) (Upper panel) The expression and conjugation of His-SUMO1WT or His-SUMO1K37Q was verified by immunoblotting using anti-His antibodies. (Middle panel) Depletion of endogenous SUMO1 and re-expression of the exogenous His-tagged versions were verified by immunoblotting using an anti-SUMO1 antibody. (Lower panel) Detection of β-tubulin served as loading control.

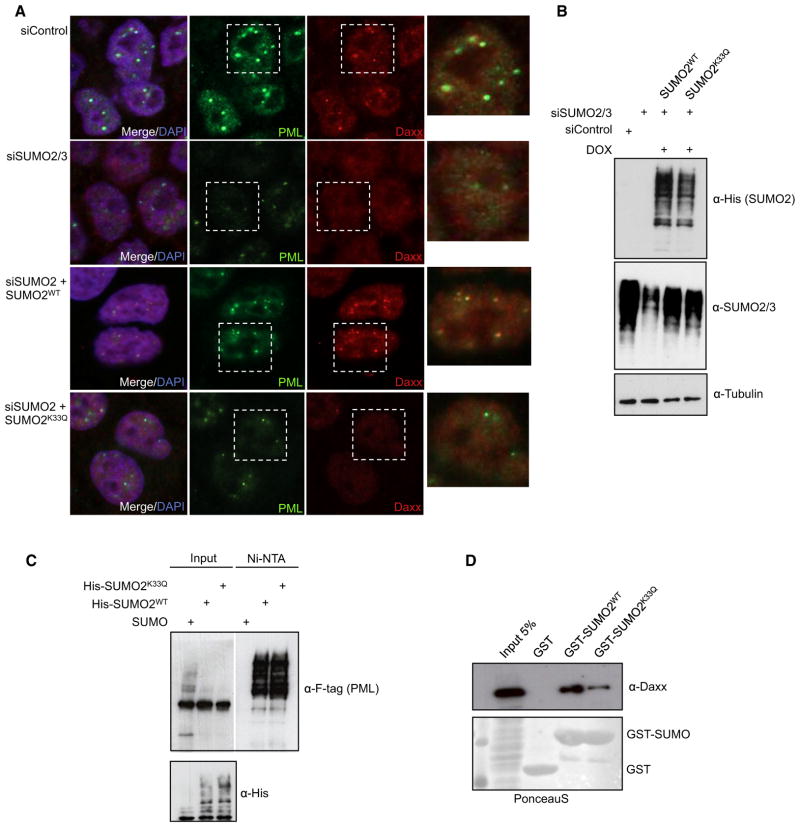

SUMO-SIM interactions are critical for the assembly and function of PML NBs (Lin et al., 2006; Matunis et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2006; Zhong et al., 2000). PML is the constitutive component of these structures and represents another major cellular target for modification by SUMO (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007). It has been shown that SUMO-modified PML triggers the recruitment of other SIM-containing factors to NBs. The best-characterized example is Daxx, which is targeted to NBs via its C-terminal SIM (Lin et al., 2006). Accordingly, in control cells PML and Daxx mainly colocalize in nuclear dots, corresponding to PML NBs (Figure 5A and Figure S7A). On depletion of either endogenous SUMO1 or SUMO2/3, no Daxx-positive dots can be detected, and the number and size of PML-positive dots are drastically reduced (Figures 5A and 5B and Figure S7A). The loss of NBs is in line with the idea that SUMO-SIM-dependent oligomerization of PML is involved in the nucleation of PML NBs (Shen et al., 2006; Zhong et al., 2000). The observation that both SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 are required for the assembly of NBs is consistent with the finding that PML is modified by SUMO1 and SUMO2/3 at distinct lysine residues (Gong and Yeh, 2006). Re-expression of wild-type SUMO1 in SUMO1-depleted cells or SUMO2 in SUMO2-depleted cells largely restores the normal appearance of PML NBs and relocates Daxx in these structures (Figure 5A and Figure S7A). These data support the model that SUMO conjugates, most likely SUMO-modified forms of PML, are essential for the recruitment of Daxx to PML NBs. Strikingly, however, re-expression of SUMO1K37Q or SUMO2K33Q failed to trigger recruitment of Daxx into NBs (Figures 5A and 5B and Figure S7A). Moreover, in many cells, PML-positive dots are considerably smaller and less numerous. Importantly, this does not result from a defect in SUMO conjugation to PML, since covalent attachment of the acetyl-mimicking SUMO variants to PML was unchanged when compared to the wild-type counterparts (Figure 5C and Figure S7B). However, in contrast to wild-type SUMO, the acetyl-mimicking SUMO1/2 variants exhibit a strongly reduced binding to endogenous Daxx, indicating that acetylation of SUMO interferes with NB recruitment of Daxx by preventing SUMO-SIM interactions (Figure 5D and Figure S7C).

Figure 5. The Acetylation of SUMO Paralogs Controls the Assembly of PML NBs.

(A) HeLa cells stably expressing wild-type His-SUMO2 or the acetyl-mimicking variant His-SUMO2K33Q under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter were either transfected with control siRNA or siRNA directed against SUMO2/3. Cells were either uninduced (upper two panels) or expression of His-tagged SUMO2 variants was induced by treatment with doxycycline (lower two panels). The localization of endogenous Daxx and PML was monitored by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-Daxx and anti-PML antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

(B) (Upper panel) The expression and conjugation of His-SUMO2WT or His-SUMO2K33Q were verified by immunoblotting using anti-His antibodies. (Middle panel) Depletion of endogenous SUMO2/3 and re-expression of the exogenous His-tagged versions were verified by immunoblotting using an anti-SUMO2/3 antibody. (Lower panel) Detection of β-tubulin served as loading control.

(C) HeLa cells stably expressing wild-type untagged SUMO2, His-SUMO2, or the acetyl-mimicking variant His-SUMO2K33Q were transfected with F-tagged PML as indicated. His-SUMO2 conjugates were captured on magnetic Ni-NTA beads and subjected to western blotting using anti-F antibodies.

(D) GST, GST-SUMO2WT, or the acetyl-mimicking variant GST-SUMO2K33Q was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with a cellular extract from HeLa cells. After intensive washing, bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by anti-Daxx immunoblotting or staining with Ponceau S.

Acetylation of SUMO Is Controlled by HDACs

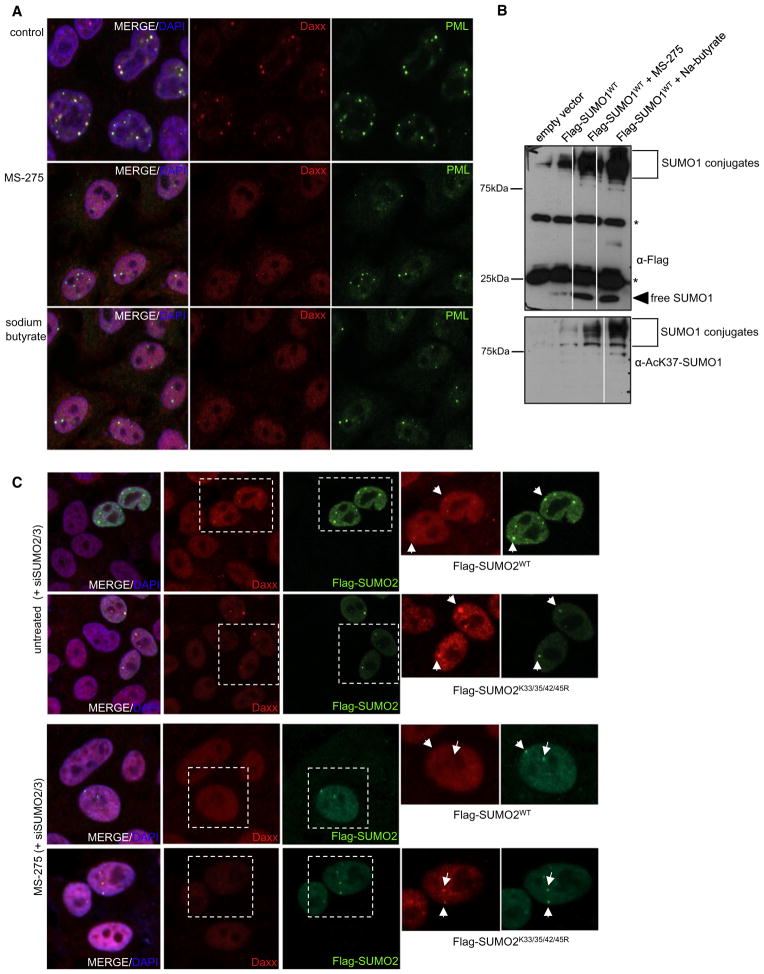

To further understand how acetylation of SUMO is regulated and how this might affect NB composition, we treated cells with different HDAC inhibitors and monitored the localization of PML and Daxx by indirect immunofluorescence (Figure 6A). A class II-specific HDAC inhibitor (MC-1568) did not affect the compartmentalization of PML and Daxx in NBs (data not shown). However, inhibition of class I HDACs by MS-275 or treatment of cells with the pan-HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate led to the release of Daxx from NBs (Figure 6A). Notably, this correlates with the induction of K37-acetylated SUMO1 conjugates as monitored by immunoblotting with the K37 acetyl-specific antibody (Figure 6B). This suggests that the loss of Daxx from PML NBs upon inhibition of HDACs results from the acetyl-mediated disruption of SUMO-SIM interactions. To further validate this point, we depleted cells from endogenous SUMO and transiently re-expressed either Flag-tagged wild-type SUMO2 or a mutant, where all four potentially acetylated lysine residues within the basic SIM-interacting surface are changed to arginine (Figure 6C). As described above, depletion of SUMO2/3 induces a loss of the punctuate distribution of Daxx in cells that are negative for Flag-SUMO2. In cells that express either wild-type SUMO2 or the acetyl-resistant SUMO1K33/35/42/45R version, this effect is reverted and Daxx colocalizes with SUMO2 in nuclear dots (Figure 6C and quantification in Figure S8). Upon treatment with the HDAC inhibitor MS-275, Daxx is released from NBs in the vast majority of cells (75%) that are expressing wild-type SUMO2. Importantly, however, in the presence of nonacetylatable SUMO2, Daxx is still found in nuclear dots in 90% of cells, thus strongly supporting the idea that the HDAC-mediated release of Daxx from NBs is directly related to acetylation of SUMO.

Figure 6. The Acetylation of SUMO Paralogs Is Dynamically Regulated by HDACs.

(A) HeLa cells were either mock treated or treated with the HDAC inhibitors MS-275 or sodium butyrate. Subsequently, the localization of endogenous Daxx and PML was monitored by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-Daxx and anti-PML antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI.

(B) HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-SUMO2 and either mock treated or treated with the HDAC inhibitors MS-275 or sodium butyrate. Flag-SUMO2 was immunoprecipitated using Flag-M2 agarose beads. Immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed using an anti-SUMO1 antibody or the acetyl-K37 lysine-specific SUMO1 antibody. Asterisks indicate heavy and light IgG bands.

(C) HeLa cells were depleted from SUMO2/3 and reconstituted with siRNA-resistant constructs expressing either wild-type Flag-tagged SUMO2 or a Flag-SUMO2K33/35/42/45R mutant. The localization of endogenous Daxx and PML was monitored by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-Daxx and anti-PML antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The inset shows representative examples of Flag-positive transfected cells.

DISCUSSION

The interconnection of posttranslational modification systems has emerged as a central principle that governs the spatiotemporal regulation of cellular signaling pathways (Hunter, 2007). The interplay of kinases and ubiquitin ligases orchestrates phosphorylation and ubiquitylation events to guarantee the specificity of substrate ubiquitylation. Similarly, attachment of SUMO can promote ubiquitylation by generating a binding platform for ubiquitin ligases that contain SUMO-binding modules (Geoffroy and Hay, 2009; Praefcke et al., 2012). Our recent work revealed a crosstalk between the ubiquitin-like SUMO system and signaling by the protein kinase CK2 (Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). Here we define site-specific acetylation of SUMO as a regulatory principle that determines the specificity and dynamics of SUMO-SIM interactions, thus directly linking SUMO signaling to acetylation.

The structural determinants for SUMO-SIM interactions have been dissected by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography (Chang et al., 2011; Hecker et al., 2006; Namanja et al., 2011; Reverter and Lima, 2005; Song et al., 2004, 2005). A common feature of all known structures is the interaction of the hydrophobic core region of SIMs, with the hydrophobic groove formed between strand β2 and helix α1 of SUMO paralogs (Gareau and Lima, 2010; Kerscher, 2007). However, biochemical and structural data revealed that electrostatic interactions between negative charges in SIM regions and the positively charged surface on SUMO contribute to SIM/SUMO interactions. Our data now demonstrate that the alteration of these charges by posttranslational modifications on either the SIM or SUMO regulates the selectivity and dynamics of SUMO-SIM interactions. Thus, addition of negative charges by phosphorylation of specific residues within SIM modules generates a binding interface with lysine 39 in SUMO1 and lysine 35 in SUMO2 (corresponding to lysine 34 in SUMO3), thereby promoting SUMO-SIM interactions (Chang et al., 2011; Hecker et al., 2006; Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). We now provide compelling evidence that the regulated acetylation of K37 in SUMO1 and K33 in SUMO2 (corresponding to lysine 32 in SUMO3) modulates selected SUMO-SIM interactions, thus adding an additional regulatory layer to the control of SUMO-mediated protein-protein interactions. A striking finding is that the acetylation controls SUMO-SIM interactions in a selective way, thus possibly priming a particular SUMO conjugate for distinct protein-protein interactions. Acetylation of SUMO1 at K37 still allows binding of RanGAP1-SUMO1 to RanBP2, most likely because the positive charge at this residue is not required for SUMO1 binding to RanBP2. By contrast, K37 acetyl-SUMO1 or K33 acetyl-SUMO2 loses the potential to interact with PML, Daxx, or PIAS. We propose that in these cases the acetylation acts as a switch that neutralizes the positive charge of lysine residues, which are critical for a productive SIM interaction. This switch could be a central mechanism to resolve SUMO-mediated protein interactions, because when bound to SIMs SUMO conjugates appear to be protected from desumoylation (Zhu et al., 2009). The temporary acetylation of a given conjugate would release it from the SIM, thus allowing access of desumoylating enzymes.

We provide evidence that this regulatory principle can control SUMO-mediated gene repression. K33 is one of the critical amino acids for the transcriptional inhibitory properties of SUMO2 and is likely involved in the binding to SIM-containing corepressors (Chupreta et al., 2005; Rosendorff et al., 2006). Structural data indeed demonstrate that K33 of SUMO2 forms a salt bridge with an aspartic acid in the SIM of the corepressor MCAF1 (Sekiyama et al., 2008). Consistent with these findings, the acetyl-mimicking SUMO2K33Q variant exhibits a strongly reduced repressive potential, indicating that SUMO-dependent gene repression is directly regulated by acetylation. Interestingly, antagonistic functions of covalent SUMO conjugation and acetylation on distinct lysine residues of transcriptional regulators have been proposed (Wilkinson and Henley, 2010). One example is MEF2A, where phosphorylation acts as a switch favoring sumoylation over acetylation (Shalizi et al., 2006). Similarly, a direct competition between sumoylation and acetylation has been reported to occur on STAT5 (Van Nguyen et al., 2012). This suggests that acetylation can counter covalent and noncovalent interactions of SUMO to overcome SUMO-mediated gene silencing.

Our biochemical experiments provide evidence that acetyl-K33 SUMO2 is specifically recognized by the bromodomain of p300. This indicates that acetylation not only prevents SUMO-SIM interactions but concomitantly promotes SUMO-bromodomain interactions. Considering that bromodomains are typically found in transcriptional coactivators, this could allow a rapid switch from a repressive to an active transcriptional state.

Another mode of SUMO-controlled gene expression appears to be the recruitment of SIM-containing transcriptional coregulators, like Daxx, to SUMO-modified PML in NBs (Bernardi and Pandolfi, 2007; Ishov et al., 1999; Matunis et al., 2006). It was initially proposed that SUMO-SIM-dependent sequestration of Daxx in NBs restrains its corepressor activity (Lehembre et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2006). More recently, however, it has been shown that SIM-mediated NB recruitment promotes the antiapoptotic gene repression by Daxx and sensitizes cells to Fas-induced apoptosis (Chang et al., 2011). This has led to the idea that at least in some cases the transient recruitment to NBs may facilitate the assembly of Daxx-containing corepressor complexes (Mukhopadhyay and Matunis, 2011). Acetylation of SUMO likely interferes with this process and may modulate the proapoptotic activity of Daxx, because our preliminary data indeed suggest that cells expressing acetylated SUMO are more resistant to Fas-induced apoptosis (R.U. and S.M., unpublished data).

The ensemble of these data indicates that site-specific acetylation of SUMO paralogs has a widespread implication on the dynamics of SUMO-SIM interactions and the control of cellular signaling pathways. DNA repair pathways, such as homologous recombination or base excision repair, also heavily rely on SUMO-SIM-dependent assembly and disassembly of protein complexes (Jentsch and Muller, 2011; van Wijk et al., 2011). It is thus tempting to speculate that acetylation will also be involved in the control of genomic stability. In support of this idea, K37 and K33 are part of the molecular interface of SUMO1 or SUMO2 with a SIM in the repair protein thymine DNA glycosylase (Baba et al., 2005, 2006).

Notably, by mass spectrometry we and others identified additional acetylation sites on SUMO paralogs within the basic SIM-binding interface, such as K39, 45, 46, or 48 of SUMO1 or K35, K42, and K45 on SUMO2 (Cheema et al., 2010; Choudhary et al., 2009; R.U. and S.M., unpublished data). This suggests that site-specific acetylation of SUMO serves as an elaborate mechanism to selectively regulate SUMO-SIM interactions. The exquisite posttranslational modification of SUMO as well as SUMO-binding modules may have evolved to expand the repertoire of binding specificities toward a single type of binding module. This is in contrast to the ubiquitin system, where many structurally distinct binding modules have evolved to mediate ubiquitin-dependent protein-protein interactions (van Wijk et al., 2011).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection

HeLa and HEK293T cells were grown under standard conditions. Generation of stable HeLa Flp-In/T-Rex cells is described in the Supplemental Information. When indicated, cells were treated with 16 μM MS-275 (Enzo Life Sciences) and 5 μM sodium butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hr. Methods for plasmid and siRNA transfections as well as siRNA sequences are detailed in the Supplemental Information.

Cloning and Mutagenesis

For transient expression of Flag- or HA-epitope-tagged proteins in mammalian cells, the respective cDNA sequences were inserted into the pCI vector (Invitrogen). For bacterial expression of GST-fusion proteins, cDNA sequences were inserted into pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare) or pCDF PylT-1 (kindly provided by Jason W. Chin, MRC Laboratory for Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK). All other plasmids are described previously (Finkbeiner et al., 2011; Haindl et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2009; Ledl et al., 2005). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChange Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Expression of Recombinant Proteins, GST-Pull-Down Experiments, and In Vitro Acetylation

GST fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 DE3, and GST-pull-down experiments were done as described (Schmidt and Muller, 2002). Protein expression and purification of site-specific acetylated SUMO, as well as experimental details for in vitro acetylation, are described in the Supplemental Information.

Immunofluorescence, Immunoprecipitation, and Ni-NTA Pull-Down

Experimental details for immunofluorescence and immunoprecipitations are given in the Supplemental Information. Ni-NTA precipitations were done as described (Muller et al., 2000).

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay, Reporter Gene Assays, and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

cDNAs encoding the respective prey or bait proteins were cloned in pGAD or pFBT9, and directed binding assays were done according to standard procedures. Reporter gene assays were done as described (Stehmeier and Muller, 2009). For ChIP experiments, 1 × 106 HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the respective Gal4-SUMO2 versions together with the reporter plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection, chromatin preparation was done as published (Nelson et al., 2006), and PCR was performed with primers described in the Supplemental Information.

Mass Spectrometry

Mass-spectrometric analysis was done in the proteomic core facility at the Max-Planck Institute, Martinsried, Germany, according to published procedures (Schiller et al., 2011). Details are given in the Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jason Chin, Thomas Mayer, and Frauke Melchior for providing valuable reagents and thank Kristina Wagner for excellent technical assistance. We are indebted to Cyril Boulegue for expert mass spectrometry. We thank Nithya Raman and Marc Sawatzki for critical reading and comments on the manuscript, and Ivan Dikic, Stefan Jentsch, and members of the Dikic and Jentsch groups for stimulating discussions and experimental advice. S.M. is supported by the “Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft” SPP1365 and SFB684, and M.L.A. was supported by grants NIH R01 CA102746 and R21CA123234.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes eight figures and Supplemental Experimental Procedures and can be found with this article online at doi:10.1016/ j.molcel.2012.04.006.

References

- Baba D, Maita N, Jee JG, Uchimura Y, Saitoh H, Sugasawa K, Hanaoka F, Tochio H, Hiroaki H, Shirakawa M. Crystal structure of thymine DNA glycosylase conjugated to SUMO-1. Nature. 2005;435:979–982. doi: 10.1038/nature03634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba D, Maita N, Jee JG, Uchimura Y, Saitoh H, Sugasawa K, Hanaoka F, Tochio H, Hiroaki H, Shirakawa M. Crystal structure of SUMO-3-modified thymine-DNA glycosylase. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi R, Pandolfi PP. Structure, dynamics and functions of promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:1006–1016. doi: 10.1038/nrm2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, Naik MT, Huang YS, Jeng JC, Liao PH, Kuo HY, Ho CC, Hsieh YL, Lin CH, Huang NJ, et al. Structural and functional roles of Daxx SIM phosphorylation in SUMO paralog-selective binding and apoptosis modulation. Mol Cell. 2011;42:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheema A, Knights CD, Rao M, Catania J, Perez R, Simons B, Dakshanamurthy S, Kolukula VK, Tilli M, Furth PA, et al. Functional mimicry of the acetylated C-terminal tail of p53 by a SUMO-1 acetylated domain, SAD. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:371–384. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chupreta S, Holmstrom S, Subramanian L, Iniguez-Lluhi JA. A small conserved surface in SUMO is the critical structural determinant of its transcriptional inhibitory properties. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4272–4282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4272-4282.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deribe YL, Pawson T, Dikic I. Post-translational modifications in signal integration. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:666–672. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner E, Haindl M, Muller S. The SUMO system controls nucleolar partitioning of a novel mammalian ribosome biogenesis complex. EMBO J. 2011;30:1067–1078. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau JR, Lima CD. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:861–871. doi: 10.1038/nrm3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffroy MC, Hay RT. An additional role for SUMO in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:564–568. doi: 10.1038/nrm2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Yeh ET. Characterization of a family of nucleolar SUMO-specific proteases with preference for SUMO-2 or SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15869–15877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haindl M, Harasim T, Eick D, Muller S. The nucleolar SUMO-specific protease SENP3 reverses SUMO modification of nucleophosmin and is required for rRNA processing. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:273–279. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay RT. SUMO-specific proteases: a twist in the tail. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker CM, Rabiller M, Haglund K, Bayer P, Dikic I. Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16117–16127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Ghisletti S, Saijo K, Gandhi M, Aouadi M, Tesz GJ, Zhang DX, Yao J, Czech MP, Goode BL, et al. Coronin 2A mediates actin-dependent de-repression of inflammatory response genes. Nature. 2011;470:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. The age of crosstalk: phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol Cell. 2007;28:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishov AM, Sotnikov AG, Negorev D, Vladimirova OV, Neff N, Kamitani T, Yeh ET, Strauss JF, 3rd, Maul GG. PML is critical for ND10 formation and recruits the PML-interacting protein daxx to this nuclear structure when modified by SUMO-1. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:221–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch S, Muller S. Regulatory functions of ubiquitin and SUMO in DNA repair pathways. Subcell Biochem. 2011;54:184–194. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6676-6_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamieniarz K, Schneider R. Tools to tackle protein acetylation. Chem Biol. 2009;16:1027–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher O. SUMO junction—what’s your function? New insights through SUMO-interacting motifs. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:550–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein UR, Haindl M, Nigg EA, Muller S. RanBP2 and SENP3 function in a mitotic SUMO2/3 conjugation-deconjugation cycle on Borealin. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:410–418. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaja N, Aittomaki S, Silvennoinen O, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. ARIP3 (androgen receptor-interacting protein 3) and other PIAS (protein inhibitor of activated STAT) proteins differ in their ability to modulate steroid receptor-dependent transcriptional activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1986–2000. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.12.0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaja N, Karvonen U, Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. PIAS proteins modulate transcription factors by functioning as SUMO-1 ligases. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5222–5234. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5222-5234.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledl A, Schmidt D, Muller S. Viral oncoproteins E1A and E7 and cellular LxCxE proteins repress SUMO modification of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor. Oncogene. 2005;24:3810–3818. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehembre F, Muller S, Pandolfi PP, Dejean A. Regulation of Pax3 transcriptional activity by SUMO-1-modified PML. Oncogene. 2001;20:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DY, Huang YS, Jeng JC, Kuo HY, Chang CC, Chao TT, Ho CC, Chen YC, Lin TP, Fang HI, et al. Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2006;24:341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R, Delphin C, Guan T, Gerace L, Melchior F. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell. 1997;88:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81862-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R, Gerace L, Melchior F. Molecular characterization of the SUMO-1 modification of RanGAP1 and its role in nuclear envelope association. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:259–270. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Coutavas E, Blobel G. A novel ubiquitin-like modification modulates the partitioning of the Ran-GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 between the cytosol and the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1457–1470. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Wu J, Blobel G. SUMO-1 modification and its role in targeting the Ran GTPase-activating protein, RanGAP1, to the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:499–509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matunis MJ, Zhang XD, Ellis NA. SUMO: the glue that binds. Dev Cell. 2006;11:596–597. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Dasso M. Modification in reverse: the SUMO proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Matunis MJ. SUMmOning Daxx-mediated repression. Mol Cell. 2011;42:4–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, Berger M, Lehembre F, Seeler JS, Haupt Y, Dejean A. c-Jun and p53 activity is modulated by SUMO-1 modification. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13321–13329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namanja AT, Li YJ, Su Y, Wong S, Lu J, Colson LT, Wu C, Li SS, Chen Y. Insights into high affinity small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) recognition by SUMO-interacting motifs (SIM) revealed by a combination of NMR and peptide array analysis. J Biol Chem. 2011;287:3231–3240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.293118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K. Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann H, Hancock SM, Buning R, Routh A, Chapman L, Somers J, Owen-Hughes T, van Noort J, Rhodes D, Chin JW. A method for genetically installing site-specific acetylation in recombinant histones defines the effects of H3 K56 acetylation. Mol Cell. 2009;36:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang J, Shi Y, Valin A, Xuan Y, Gill G. Direct binding of CoREST1 to SUMO-2/3 contributes to gene-specific repression by the LSD1/CoREST1/HDAC complex. Mol Cell. 2009;34:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palvimo JJ. PIAS proteins as regulators of small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) modifications and transcription. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1405–1408. doi: 10.1042/BST0351405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual G, Fong AL, Ogawa S, Gamliel A, Li AC, Perissi V, Rose DW, Willson TM, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2005;437:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praefcke GJ, Hofmann K, Dohmen RJ. SUMO playing tag with ubiquitin. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reverter D, Lima CD. Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO-RanGAP1-Ubc9-Nup358 complex. Nature. 2005;435:687–692. doi: 10.1038/nature03588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendorff A, Sakakibara S, Lu S, Kieff E, Xuan Y, DiBacco A, Shi Y, Gill G. NXP-2 association with SUMO-2 depends on lysines required for transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5308–5313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601066103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthenburg AJ, Li H, Patel DJ, Allis CD. Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:983–994. doi: 10.1038/nrm2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytinki MM, Kaikkonen S, Pehkonen P, Jaaskelainen T, Palvimo JJ. PIAS proteins: pleiotropic interactors associated with SUMO. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3029–3041. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller HB, Friedel CC, Boulegue C, Fassler R. Quantitative proteomics of the integrin adhesome show a myosin II-dependent recruitment of LIM domain proteins. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:259–266. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Muller S. Members of the PIAS family act as SUMO ligases for c-Jun and p53 and repress p53 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2872–2877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052559499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Muller S. PIAS/SUMO: new partners in transcriptional regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2561–2574. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seet BT, Dikic I, Zhou MM, Pawson T. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:473–483. doi: 10.1038/nrm1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama N, Ikegami T, Yamane T, Ikeguchi M, Uchimura Y, Baba D, Ariyoshi M, Tochio H, Saitoh H, Shirakawa M. Structure of the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)-interacting motif of MBD1-containing chromatin-associated factor 1 bound to SUMO-3. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35966–35975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalizi A, Gaudilliere B, Yuan Z, Stegmuller J, Shirogane T, Ge Q, Tan Y, Schulman B, Harper JW, Bonni A. A calcium-regulated MEF2 sumoylation switch controls postsynaptic differentiation. Science. 2006;311:1012–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen TH, Lin HK, Scaglioni PP, Yung TM, Pandolfi PP. The mechanisms of PML-nuclear body formation. Mol Cell. 2006;24:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Durrin LK, Wilkinson TA, Krontiris TG, Chen Y. Identification of a SUMO-binding motif that recognizes SUMO-modified proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14373–14378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403498101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Zhang Z, Hu W, Chen Y. Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) recognition of a SUMO binding motif: a reversal of the bound orientation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40122–40129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehmeier P, Muller S. Phospho-regulated SUMO interaction modules connect the SUMO system to CK2 signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;33:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stielow B, Sapetschnig A, Kruger I, Kunert N, Brehm A, Boutros M, Suske G. Identification of SUMO-dependent chromatin-associated transcriptional repression components by a genome-wide RNAi screen. Mol Cell. 2008;29:742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Kim S, Jaffray E, Song J, Chen Y, Hay RT. Unique binding interactions among Ubc9, SUMO and RanBP2 reveal a mechanism for SUMO paralog selection. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:67–74. doi: 10.1038/nsmb878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna SD, Li H, Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Patel DJ. How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1025–1040. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nguyen T, Angkasekwinai P, Dou H, Lin FM, Lu LS, Cheng J, Chin YE, Dong C, Yeh ET. SUMO-specific protease 1 is critical for early lymphoid development through regulation of STAT5 activation. Mol Cell. 2012;45:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk SJ, Muller S, Dikic I. Shared and unique properties of ubiquitin and SUMO interaction networks in DNA repair. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1763–1769. doi: 10.1101/gad.17593511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venteclef N, Jakobsson T, Ehrlund A, Damdimopoulos A, Mikkonen L, Ellis E, Nilsson LM, Parini P, Janne OA, Gustafsson JA, et al. GPS2-dependent corepressor/SUMO pathways govern anti-inflammatory actions of LRH-1 and LXRbeta in the hepatic acute phase response. Genes Dev. 2010;24:381–395. doi: 10.1101/gad.545110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KA, Henley JM. Mechanisms, regulation and consequences of protein SUMOylation. Biochem J. 2010;428:133–145. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Muller S, Ronchetti S, Freemont PS, Dejean A, Pandolfi PP. Role of SUMO-1-modified PML in nuclear body formation. Blood. 2000;95:2748–2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Zhu S, Guzzo CM, Ellis NA, Sung KS, Choi CY, Matunis MJ. Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) binding determines substrate recognition and paralog-selective SUMO modification. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29405–29415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803632200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Goeres J, Sixt KM, Bekes M, Zhang XD, Salvesen GS, Matunis MJ. Protection from isopeptidase-mediated deconjugation regulates paralog-selective sumoylation of RanGAP1. Mol Cell. 2009;33:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.