Abstract

Background

Release from prison is associated with a markedly increased risk of both fatal and non-fatal drug overdose, yet the risk factors for overdose in recently released prisoners are poorly understood. The aim of this study was to identify risk and protective factors for non-fatal overdose (NFOD) among a cohort of illicit drug users in Vancouver, Canada, according to recent incarceration.

Methods

Prospective cohort of 2515 community-recruited illicit drug users in Vancouver, Canada, followed from 1996 to 2010. We examined factors associated with NFOD in the past six months separately among those who did and did not also report incarceration in the last six months.

Results

One third of participants (n=829, 33.0%) reported at least one recent NFOD. Among those recently incarcerated, risk factors independently and positively associated with NFOD included daily use of heroin, benzodiazepines, cocaine or methamphetamine, binge drug use, public injecting and previous NFOD. Older age, methadone maintenance treatment and HIV seropositivity were protective against NFOD. A similar set of risk factors was identified among those who had not been incarcerated recently.

Conclusions

Among this cohort, and irrespective of recent incarceration, NFOD was associated with a range of modifiable risk factors including more frequent and riskier patterns of drug use. Not all ex-prisoners are at equal risk of overdose and there remains an urgent need to develop and implement evidence-based preventive interventions, targeting those with modifiable risk factors in this high risk group.

Keywords: Overdose, Ex-prisoners, Drug users

1. Introduction

Release from prison is associated with a markedly increased risk of fatal drug overdose, particularly in the weeks immediately following discharge. Evidence from record linkage studies suggests that the risk of drug-related death is orders of magnitude higher among ex-prisoners than among their community peers (Binswanger et al., 2007; Farrell & Marsden, 2008; Kariminia et al., 2007; Rosen, Schoenbach, & Wohl, 2008; Stewart, Henderson, Hobbs, Ridout, & Knuiman, 2004), and between 3 and 8 times higher in the first two weeks than the subsequent ten weeks (Merrall et al., 2010). Although it is often assumed that the key driver of overdose risk for ex-prisoners is reduced drug tolerance (Merrall et al., 2010; Seaman, Brettle, & Gore, 1998; Strang et al., 2003), empirical support for this view remains weak (Kinner, 2010).

Reducing the incidence of overdose among recently released prisoners requires an understanding of who is most at risk and why, so that interventions to prevent or effectively respond to overdose events can be appropriately targeted and tailored (Darke, 2008). Unfortunately, although record linkage studies have identified that ex-prisoners are at increased risk of overdose death, limitations of routinely collected data mean that few risk factors for fatal overdose in this population have been identified (Kinner, 2010). Existing evidence suggests that those most at risk have served multiple prison sentences, lack post-release support from a spouse or partner, and have a history of illicit opiate use (Graham, 2003; Hobbs et al., 2006a; Rosen et al., 2008; Seaman et al., 1998; Singleton, Pendry, Taylor, Farrell, & Marsden, 2003). Findings regarding age and ethnic minority status have been mixed, with some studies finding that older and ethnic minority ex-prisoners are at greater risk (Hobbs et al., 2006b; Stewart et al., 2004; Tobin, Hua, Costenbader, & Latkin, 2007), while others have found the converse (Farrell & Marsden, 2005; Graham, 2003). Perhaps reflecting reduced drug tolerance, one study has identified abstinence from drug use in prison as a risk factor for drug-related death post-release (Singleton et al., 2003), while engagement in prison-based methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) appears to be protective (Dolan et al., 2005; Kinlock, Gordon, Schwartz, Fitzgerald, & O’Grady, 2009).

Nonfatal overdose (NFOD) is estimated to be between 20 and 30 times more common than fatal overdose (Darke, Mattick, & Degenhardt, 2003), and is associated with significant morbidity (Warner-Smith, Darke, & Day, 2002). Relatively few studies have explored risk factors for NFOD (Strang, 2002) and although the causes of fatal and non-fatal overdose are likely to be similar (Warner-Smith, Darke, Lynskey, & Hall, 2001), very few studies have examined NFOD among ex-prisoners. Most studies of NFOD have followed cohorts of injecting drug users (IDU), and a history of recent incarceration consistently emerges as a key risk factor (Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007; Seal et al., 2001; Yin et al., 2007). Other identified risk factors include homelessness, a history of multiple arrests and/or imprisonments, longer prison sentences, detoxification in the past year, riskier patterns of injecting such as public injecting and binge drug use, and regular or concurrent use of multiple drugs including heroin, alcohol, benzodiazepines and cocaine (Coffin et al., 2007; Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007; Seal et al., 2001; Sergeev, Karpets, Sarang, & Tikhonov, 2003; Yin et al., 2007). Consistent with the findings from record linkage studies, MMT appears to be protective (Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007), as does older age (Coffin et al., 2007; Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007; Seal et al., 2001). Although empirical evidence remains limited, it has been argued that systemic disease, particularly hepatic disease associated with hepatitis C infection, may increase the risk of overdose (Warner-Smith et al., 2001).

Given the high incidence of overdose among those recently released from prison, and limited knowledge of the risk factors for NFOD among this population, the aims of the present study were to (a) document the incidence of NFOD among a large cohort of illicit drug users in Vancouver, Canada, separately for those who had and had not experienced incarceration recently, and (b) in a multivariate model, identify risk and protective factors for NFOD among this cohort, separately for those who had and had not experienced incarceration recently.

2. Methods

The Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Access to Survival Services (ACCESS) are open prospective cohorts of illicit drug-using individuals who have been recruited through self-referral and street outreach from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside since May 1996. Those recruited into the VIDUS cohort are HIV-negative and must have injected an illicit drug at least once in the past six months. Those recruited into the ACCESS cohort are HIV-positive and must have used an illicit drug other than or in addition to cannabis in the last 30 days. Members of the VIDUS cohort who seroconvert during follow-up are automatically transferred into the ACCESS cohort.

At baseline and every six months, participants in both cohorts provide venous blood samples for HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) testing and complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire covering demographic characteristics, information about drug use and related harms, HIV risk behavior, contact with the criminal justice system and enrolment in drug treatment. All participants provide informed, written consent and receive a CA$20 stipend at each study visit. The study has been approved by the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board.

The present analyses included all participants who were enrolled into either VIDUS or ACCESS between May 1996 and May 2010 (N=2515). The primary endpoint was self-reported NFOD during the previous six months. Because the focus of the study was NFOD in the community, interviews conducted in prison settings (n=424) were excluded. Information on the primary drug involved in overdose was collected from 2001 onwards.

Explanatory variables were selected from those identified in the literature and included demographic characteristics, patterns of drug use, methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), HIV and HCV serostatus. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, Aboriginal ancestry, marital status, employment status, living alone and current homelessness. Drug use variables included daily use of heroin, cocaine, speedballs (cocaine and heroin in combination), methamphetamine, morphine, benzodiazepines and >4 alcoholic drinks; binge drug use and public injecting. For those who reported recent incarceration, additional explanatory variables included drug injection in prison and, as a proxy for sentence length, incarceration setting (local/provincial/federal). In Canada, incarceration in local jails typically lasts for days or weeks, sentences in provincial prisons are up to two years less a day, and all sentences of two years or more are served in federal penitentiaries. All time-variant variables referred to the last six months unless otherwise specified.

In order to explore whether the risk factors for NFOD differed as a function of recent incarceration, the sample was divided into those who did and did not report incarceration in the last six months. Within each sub-group, we first graphed the annual crude incidence rate of NFOD per 1000 person years, by dividing the number of NFODs reported in each calendar year (1996–2010) by the total person years of observation in that year (defined as the number of observations divided by two), divided by 1000. Next we examined univariate associations between potential explanatory variables and NFOD using Pearson’s Chi-Square test and the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test; variables significant at p<0.10 were included in subsequent multivariate analyses. Because the analysis included repeated measures of potential explanatory variables for each participant, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) for binary outcomes with logit link for the analysis of correlated data, to identify factors independently associated with NFOD (Liang & Zeger, 1986). Multivariate model building proceeded according to the protocol outlined by Pan (2001).

3. Results

Between May 1996 and May 2010 2515 participants were recruited into the study, contributing a total of 21,798 eligible observations across a median of six follow-up visits (IQR=2–14). Among this cohort 829 (33.0%) participants reported a total of 1587 NFODs. Among those recently incarcerated who experienced NFOD, 215 (39%) identified the primary drug involved: 81.4% identified a CNS depressant (typically heroin), while 18.1% identified only a stimulant (typically cocaine). Among those who experienced NFOD and had not been incarcerated recently 637 (62%) identified the primary drug involved: 77.2% identified a CNS depressant and 22.3% identified only a stimulant.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for those who did and did not report recent incarceration at baseline. Factors positively associated with recent incarceration included younger age; male gender; homelessness; unemployment; prior incarceration; daily use of heroin, cocaine, speedballs, morphine and benzodiazepines; recent binge drug use and public injecting; and history of overdose. Factors negatively associated with recent incarceration at baseline included HIV infection, living alone and MMT.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for those who did and did not report recent incarceration at baseline.

| Recent incarceration | No recent incarceration | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=686 | N=1829 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Mean age in years (range) | 35.69 (16.56–56.81) | 39.46 (13.26–58.28) | <0.0001 |

| Female | 205 (29.88) | 657 (35.92) | 0.0045 |

| Aboriginal ancestry | 200 (29.15) | 540 (29.52) | 0.8562 |

| Married | 143 (20.85) | 390 (21.32) | 0.7941 |

| Living alone | 349 (50.87) | 1013 (55.39) | 0.0432 |

| Homeless | 147 (21.43) | 256 (14.00) | <0.0001 |

| Formal employmenta | 104 (15.16) | 389 (21.27) | 0.0006 |

| Daily heroin usea | 355 (51.75) | 603 (32.97) | <0.0001 |

| Daily cocaine usea | 276 (40.23) | 483 (26.41) | <0.0001 |

| Daily speedball usea | 134 (19.53) | 159 (8.69) | <0.0001 |

| Daily methamphetamine usea | 16 (2.33) | 39 (2.13) | 0.7600 |

| Daily morphine usea | 24 (3.50) | 41 (2.24) | 0.0769 |

| Daily benzodiazepine usea | 65 (9.48) | 104 (5.69) | 0.0007 |

| Daily alcohol use >4 drinksa | 55 (8.02) | 110 (6.01) | 0.0707 |

| MMT | 95 (13.85) | 416 (22.74) | <0.0001 |

| Binge drug usea | 318 (46.36) | 680 (37.18) | <0.0001 |

| Public injectinga | 224 (32.65) | 359 (19.63) | <0.0001 |

| Injected while incarcerateda | 65 (9.48) | – | – |

| Where incarcerated recentlya | |||

| Local jail | 432 (62.97) | – | – |

| Provincial prison | 236 (34.40) | – | – |

| Federal prison | 18 (2.62) | – | – |

| HIV seropositive | 155 (22.59) | 515 (28.16) | 0.0049 |

| HCV seropositive | 580 (84.55) | 1487 (81.30) | 0.0580 |

| Previous imprisonment | 682 (99.42) | 1316 (71.95) | <0.0001 |

| Non-fatal overdose | |||

| Last six months | 133 (19.39) | 217 (11.86) | <0.0001 |

| Ever | 397 (57.87) | 924 (50.52) | 0.0010 |

In the last six months.

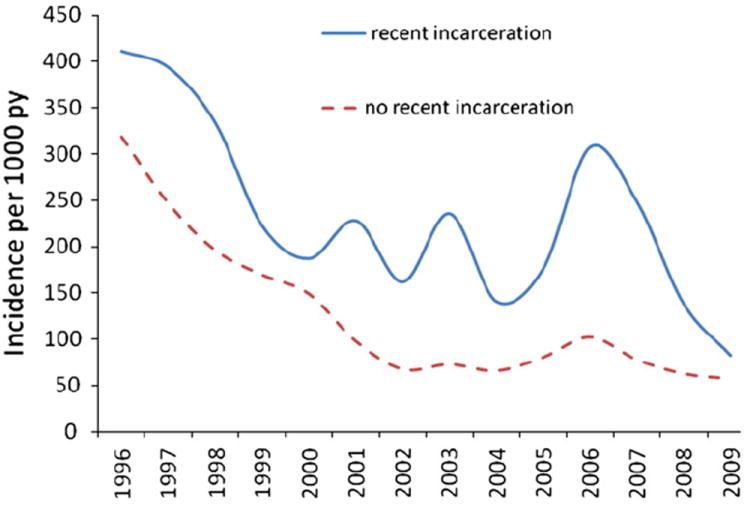

Fig. 1 shows the crude incidence rate of NFOD per 1000 person years of observation, among those who did and did not report recent incarceration, by year 1996–2010. Over this 15 year period those reporting recent incarceration experienced a total of 554 NFODs giving a crude incidence rate of 262.7 per 1000 person years of observation, compared with 1035 NFODs and a crude incidence rate of 117.7 per 1000 person years among those who did not report recent incarceration. Those recently incarcerated were significantly more likely to report recent NFOD (OR=2.13, 95%CI 1.89–2.40, p<0.001).

Fig. 1.

Incidence rate of NFOD per 1000 person years, 1996–2009, among those who did and did not report recent incarceration.

Factors associated with NFOD among those who did and did not report recent incarceration are shown in Table 2. Among those who reported recent incarceration, factors significantly associated with NFOD in univariate GEE analyses included younger age; homelessness; daily use of heroin, cocaine, speedballs, methamphetamine and benzodiazepines; binge drug use and public injecting; drug injection while incarcerated; and previous NFOD. MMT and HIV infection were protective. Among those who did not report recent incarceration, the same factors were significant, except that daily alcohol use emerged as an additional risk factor, and both previous (not recent) incarceration and HCV exposure were significantly protective.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with non-fatal overdose among individuals who did and did not report recent incarceration.

| Recently incarcerated

|

Not recently incarcerated

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||

| Per year older | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female vs. male | 1.14 (0.91–1.44) | 1.20 (1.00–1.42) | ||

| Aboriginal ancestry | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 0.89 (0.69–1.13) | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.30 (1.04–1.62) | 1.76 (1.44–2.15) | 1.31 (1.04–1.64) | |

| Formal employmenta | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.11 (0.85–1.44) | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married vs. other | 1.04 (0.82–1.31) | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) | ||

| Live alone | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.12 (0.93–1.35) | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | ||

| Heroin injectiona | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.80 (1.48–2.18) | 1.29 (1.05–1.59) | 2.24 (1.94–2.59) | 1.33 (1.14–1.57) |

| Cocaine injectiona | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.91 (1.59–2.29) | 1.49 (1.22–1.83) | 2.62 (2.26–3.03) | 1.72 (1.47–2.03) |

| Speedball injectiona | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.75 (1.39–2.22) | 2.21 (1.78–2.75) | ||

| MA usea | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.78 (1.05–3.03) | 1.98 (1.21–3.22) | 2.14 (1.38–3.32) | 1.97 (1.21–3.19) |

| Morphine usea | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.01 (0.56–1.83) | 1.33 (0.88–1.99) | ||

| Benzodiazepine usea | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.96 (1.37–2.81) | 1.90 (1.29–2.80) | 2.44 (1.92–3.11) | 2.11 (1.62–2.75) |

| Alcohol use >4 drinksa | ||||

| ≥Daily vs. less | 1.26 (0.91–1.75) | 1.40 (1.14–1.71) | 1.28 (1.03–1.60) | |

| MMT | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 0.56 (0.42–0.74) | 0.64 (0.48–0.85) | 0.45 (0.38–0.55) | 0.60 (0.50–0.72) |

| Binge drug usea | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 2.02 (1.69–2.41) | 1.67 (1.38–2.03) | 2.68 (2.35–3.05) | 2.09 (1.82–2.40) |

| Public injectinga | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.64 (1.35–2.00) | 1.34 (1.10–1.65) | 2.38 (2.01–2.82) | 1.46 (1.21–1.76) |

| Where incarcerateda | ||||

| Provincial vs. local | 0.89 (0.74–1.07) | – | ||

| Federal vs. local | 0.64 (0.33–1.24) | – | ||

| Previous incarceration | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.00 (0.65–1.54) | 0.73 (0.61–0.88) | 0.80 (0.66–0.96) | |

| Inject while incara | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.52 (1.11–2.08) | – | ||

| Previous NFOD | ||||

| Yes vs. no | 3.60 (2.77–4.68) | 3.87 (2.97–5.03) | 3.04 (2.52–3.66) | 3.41 (2.83–4.12) |

| HIV-serostatus | ||||

| Positive vs. negative | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.77 (0.61–0.99) | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | |

| HCV-serostatus | ||||

| Positive vs. negative | 1.37 (0.93–2.01) | 0.74 (0.57–0.95) | ||

In the last six months.

Table 2 also shows factors independently associated with NFOD in multivariate GEE analysis, separately for those who did and did not report recent incarceration. Among those reporting recent incarceration, NFOD was independently associated with daily use of heroin (AOR=1.29, 95%CI 1.05–1.59), cocaine (AOR=1.49, 95%CI 1.22–1.83), methamphetamine (AOR=1.98, 95%CI 1.21–3.22) and benzodiazepines (AOR=1.90, 95%CI 1.29–2.80); binge drug use (AOR=1.67, 95%CI 1.38–2.03) and public injecting (AOR=1.34, 95%CI 1.10–1.65); and previous NFOD (AOR=3.87, 95%CI 2.97–5.03). Being older (AOR=0.98 per year, 95%CI 0.97–0.99), HIV positive (AOR=0.77, 95%CI 0.61–0.99) and receiving MMT (AOR=0.64, 95%CI 0.48–0.85) were protective. Among those who did not report recent incarceration a similar pattern emerged, except that homelessness (AOR=1.31, 95%CI 1.04–1.64) and daily alcohol use (AOR=1.28, 95%CI 1.03–1.60) emerged as additional risk factors, previous (not recent) incarceration was protective (AOR=0.80, 95%CI 0.66–0.96), and being HIV positive was not significantly protective (p>0.05).

Given the unexpected protective effect of HIV for those recently incarcerated, we computed all two-way interactions between HIV and other factors significant in the multivariate model. The interaction between HIV and age was significant (p=0.02), and in a subsequent test of interaction effects (see Table 3) HIV emerged as protective for those ≤38 years of age (AOR=0.65, 95%CI 0.47–0.88), whereas among those who were HIV negative, being aged >38 years was protective (AOR=0.74, 95%CI 0.58–0.95).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of interaction between HIV infection and age, among those recently incarcerated.

| HIV serostatus | Age (median split) | AORa | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | ≤38 years | 1.00 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Negative | >38 years | 0.74 | 0.58–0.95 | 0.0180 |

| Positive | ≤38 years | 0.65 | 0.47–0.88 | 0.0053 |

| Positive | >38 years | 0.70 | 0.48–1.02 | 0.0639 |

Adjusted for daily use of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and benzodiazepines; MMT; binge drug use; public drug use; previous NFOD.

4. Discussion

In the present study we found that among a large cohort of illicit drug users, the incidence of NFOD was significantly higher among those who had experienced recent incarceration. However, the risk factors for NFOD were very similar for those who had and had not experienced recent incarceration, indicating that preventive interventions designed for community-based illicit drug users may also be appropriate for those recently released from prison. Given that most of the risk factors identified pertain to behaviors and circumstances in the community, preventive interventions delivered prior to release should be coupled with community-based interventions after release (Freudenberg, Daniels, Crum, Perkins, & Richie, 2005; Kinner, 2010; WHO, 2010).

Although many IDU continue to use and inject drugs in prison (Calzavara et al., 2003; Dolan et al., 2010; Jürgens, Ball, & Verster, 2009), much of the debate regarding prevention of overdose in ex-prisoners has focused on reduced drug tolerance (Merrall et al., 2010; Seaman et al., 1998; Strang et al., 2003). Although we were unable to directly measure drug tolerance, our finding that drug injection in prison was a risk factor for NFOD seems inconsistent with the view that reduced drug tolerance is the overriding risk factor. Although it is highly likely that drug tolerance is one important factor, this study has identified a range of other, modifiable risk factors for NFOD, which are very similar to those identified for illicit drug users who have not been incarcerated recently.

The finding that more frequent, riskier patterns of drug injection was a risk factor for NFOD is not new (Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007), although this study confirms that the same is true for illicit drug users who have been incarcerated recently. Regardless of recent incarceration, risk of NFOD was increased for those reporting public injection or binge drug use. Previous work has shown that accessing a supervised injection facility (SIF) is associated with a reduction in public drug use and other risky injecting practices (Stoltz et al., 2007), and that SIFs can reduce overdose morbidity (Kerr, Small, Moore, & Wood, 2007; Kerr, Tyndall, Lai, Montaner, & Wood, 2006) and mortality (Milloy, Kerr, Tyndall, Montaner, & Wood, 2008). Given the elevated incidence of NFOD among those recently incarcerated in this study, there is a clear case for routinely linking incarcerated IDU with a SIF, where available, both via in-reach before release and as part of a broader case management approach after release from custody.

Also consistent with previous research (Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007; Ochoa et al., 2005), and regardless of recent incarceration history, risk of NFOD in this study was elevated for those reporting daily use of heroin, benzodiazepines, cocaine or methamphetamines. We were unable to determine whether these drugs were used sequentially or in combination, however our findings demonstrate that a range of drugs – both depressants and stimulants – are implicated in overdose among those recently incarcerated. In addition to cautioning prisoners that their opiate tolerance may be reduced post-release, preventive interventions should incorporate messages about the risk of overdose associated with stimulant drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine.

Previous studies have identified a link between in-prison MMT and reduced overdose mortality post-release (Dolan et al., 2005; Kinlock et al., 2009), although it remains unclear whether in-prison MMT confers a direct protective effect through increased opiate tolerance at the point of release, or an indirect protective effect by increasing the likelihood of accessing MMT in the community. In this study, regardless of recent incarceration, current MMT was associated with reduced risk of NFOD, highlighting both the benefits of MMT as a harm reduction measure and the particular importance of continuity in treatment provision for IDU returning from custody to the community (Dolan et al., 2005; Kinner, 2006; Larney, Toson, Burns, & Dolan, 2012; Møller et al., 2010; Palepu et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008). Irrespective of recent incarceration, risk of NFOD also decreased with increasing age. Although inconsistent with the view that age-related systemic dysfunction should increase the risk of overdose (Warner-Smith et al., 2001), these findings are consistent with those of other studies (Coffin et al., 2007; Kerr, Fairbairn, et al., 2007) and may indicate that older illicit drug users are ‘aging out’ of the risky behaviors that increase risk of NFOD. This interpretation is consistent with evidence that impulse control is a risk factor for NFOD (Hakansson, Schlyter, & Berglund, 2008) and that impulsivity declines with age (Steinberg et al., 2008).

Among those recently incarcerated, risk of NFOD was lower for those who were HIV positive, although this was only true for younger ex-prisoners. One interpretation of this finding is that among younger ex-prisoners, HIV diagnosis was associated with increased access to care and treatment, and a corresponding reduction in overdose risk behaviors. By contrast, given the high prevalence of HIV among the cohort, among older users remaining uninfected with HIV may have been a marker for lower levels of overdose risk behavior. Although potentially important, it remains unclear why this marginally significant finding was observed and future research could further explore these dynamics.

In this study the most powerful predictor of NFOD was past experience of overdose. Among those who had been incarcerated recently, the risk of NFOD was almost four times greater for those who had also overdosed in the past. This finding adds to a growing literature (Coffin et al., 2007; Darke et al., 2007; Stoové, Dietze, & Jolley, 2009) suggesting that previous overdose experience does not increase the perception of risk for subsequent overdose (Darke & Ross, 1997), but rather increases risk. In the context of limited resources for prisoner and ex-prisoner health initiatives (Belenko & Peugh, 2005; Levy, 2005), identification of those most at risk of overdose may allow for more effective allocation of limited resources for prevention. In addition to education and case management, this may include provision of naloxone to those considered at high risk (Ochoa et al., 2005; Wakeman, Bowman, McKenzie, Jeronimo, & Rich, 2009).

This study has limitations that should be noted. One limitation is use of self-report, however self-report can be reliable with hard-to-reach populations (Darke, 1998) and is arguably the most appropriate way to measure NFOD, since many NFODs are not attended by emergency services or police and are therefore not documented elsewhere (Darke, Ross, & Hall, 1996; Dietze, Cvetkovski, Rumbold, & Miller, 2000). Further, we have no reason to believe that NFODs would be differentially reported by those who were and were not recently incarcerated. Second, the binary nature of the outcome – any NFOD in the last six months – means that we under-estimated the incidence of NFOD, because we were unable to determine how many times a participant had overdosed in this time. Again, we have no reason to suspect that this would selectively impact those who were or were not recently incarcerated. Third, due to limited statistical power we were unable to conduct our analyses separately for depressant and stimulant overdoses. Although the vast majority of NFODs in both groups were attributed to depressant drugs (usually heroin), the risk factors for stimulant overdoses may differ, and should be the subject of further investigation. Fourth, our sample was not randomly selected and therefore our findings may not be generalizable to all illicit drug users in Vancouver or elsewhere. A final limitation is that among those recently incarcerated, we were unable to confirm that the NFOD occurred after, rather than before, incarceration. However, the markedly elevated incidence of NFOD among those recently incarcerated is consistent with evidence of increased incidence of fatal OD after release from custody (Binswanger et al., 2007; Farrell & Marsden, 2008; Kariminia et al., 2007; Merrall et al., 2010; Rosen et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2004), which suggests that at least the majority of NFODs among those recently incarcerated occurred after release from custody.

In summary, among a large, community-recruited sample of illicit drug users this study identified a range of modifiable risk factors for NFOD, and found that these risk factors were similar for those who had and had not experienced incarceration recently. However, the incidence of NFOD was higher among those incarcerated recently, highlighting the urgent need for implementation of evidence-based preventive measures both before release and importantly, after return to the community. Further research is required to understand the causal mechanisms underpinning overdose in ex-prisoners, so that such interventions can be appropriately targeted and tailored.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA011591/R01DA021525) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (RAA-79918/MOP-79297). Stuart Kinner is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (1004765/569897). Thomas Kerr is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. M-J Milloy is supported by a doctoral research award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Funding sources had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the manuscript or submission of the manuscript.

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Peter Vann, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors

Authors Kerr and Wood designed the study. Authors Qi and Zhang undertook the statistical analyses. Author Kinner wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Belenko S, Peugh J. Estimating drug treatment needs among state prison inmates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, et al. Release from prison — A high risk of death for former inmates. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzavara LM, Burchell AN, Schlossberg J, Myers T, Escobar M, Wallace E, et al. Prior opiate injection and incarceration history predict injection drug use among inmates. Addiction. 2003;98:1257–1265. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Tracy M, Bucciarelli A, Ompad D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Identifying injection drug users at risk of nonfatal overdose. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007;14:616–623. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. From the can to the coffin: Deaths among recently released prisoners. Addiction. 2008;103:256–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Mattick RP, Degenhardt L. The ratio of non-fatal to fatal heroin overdose. Addiction. 2003;98:1169–1171. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J. Overdose risk perceptions and behaviours among heroin users in Sydney, Australia. European Addiction Research. 1997;3:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J, Hall W. Overdose among heroin users in Sydney, Australia: II. Responses to overdose. Addiction. 1996;91:413–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91341310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Williamson A, Ross J, Mills K, Havard A, Teesson M. Patterns of nonfatal heroin overdose over a 3-year period: Findings from the Australian treatment outcome study. Journal of Urban Health. 2007;84:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietze PM, Cvetkovski S, Rumbold G, Miller P. Ambulance attendance at heroin overdose in Melbourne: The establishment of a database of Ambulance Service records. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2000;19:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA, Shearer J, White B, Zhou J, Kaldor J, Wodak AD. Four-year follow-up of imprisoned male heroin users and methadone treatment: mortality, re-incarceration and hepatitis C infection. Addiction. 2005;100:820–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan K, Teutsch S, Scheuer N, Levy M, Rawlinson W, Kaldor J, Lloyd A, Haber P. Incidence and risk for acute hepatitis C infection during imprisonment in Australia. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(2):143–148. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Marsden J. Drug-related mortality among newly released offenders 1998 to 2000. London: UK Home Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Marsden J. Acute risk of drug-related death among newly released prisoners in England and Wales. Addiction. 2008;103:251–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: The social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1725–1736. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.056325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A. Post-prison mortality: unnatural death among people released from victorian prisons between January 1990 and December 1999. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology. 2003;36:94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson A, Schlyter F, Berglund M. Factors associated with history of non-fatal overdose among opioid users in the Swedish criminal justice system. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs M, Krazlan K, Ridout S, Mai Q, Knuiman M, Chapman R. Mortality and morbidity in prisoners after release from prison in Western Australia 1995–2003. In: Makkai T, editor. Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs M, Krazlan K, Ridout S, Mai Q, Knuiman M, Chapman R. Mortality and morbidity in prisoners after release from prison in Western Australia 1995–2003. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens R, Ball A, Verster A. Interventions to reduce HIV transmission related to injecting drug use in prison. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2009;9:57–66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariminia A, Butler TG, Corben SP, Levy MH, Grant L, Kaldor JM, et al. Extreme cause specific mortality in a cohort of adult prisoners — 1998 to 2002: A data-linkage study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;36:310–318. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Fairbairn N, Tyndall M, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner JS, et al. Predictors of non-fatal overdose among a cohort of polysubstance-using injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Moore D, Wood E. A micro-environmental intervention to reduce the harms associated with drug-related overdose: Evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s safer injection facility. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Tyndall M, Lai C, Montaner JS, Wood E. Drug-related overdoses within a medically supervised safer injection facility. The International Journal on Drug Policy. 2006;17:436–441. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: Results at 12 months postrelease. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinner SA. Continuity of health impairment and substance misuse among adult prisoners in Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Prisoner Health. 2006;2:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kinner SA. Understanding mortality and health outcomes for ex-prisoners: First steps on a long road. Addiction. 2010;105:1555–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larney S, Toson B, Burns L, Dolan K. Effect of prison-based opioid substitution treatment and post-release retention in treatment on risk of re-incarceration. Addiction. 2012;107:372–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. Prisoner health care provision: Reflections from Australia. International Journal of Prisoner Health. 2005;1:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Merrall ELC, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, et al. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105:1545–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Tyndall M, Montaner J, Wood E. Estimated drug overdose deaths averted by North America’s first medically-supervised safer injection facility. PloS One. 2008;3:e3351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller LF, Matic S, van den Bergh BJ, Moloney K, Hayton P, Gatherer A. Acute drug-related mortality of people recently released from prisons. Public Health. 2010;124:637–639. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa KC, Davidson PJ, Evans JL, Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Moss AR. Heroin overdose among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Chan K, Wood E, Montaner JSG, Hogg RS. Initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy and continuity of HIV care: the impact of incarceration and prison release on adherence and HIV treatment outcomes. Antiviral Therapy. 2004;9:713–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among men released from state prison, 1980–2005. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:2278–2284. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Kral AH, Gee L, Moore LD, Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, et al. Predictors and prevention of nonfatal overdose among street-recruited injection heroin users in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1998–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1842–1846. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman SR, Brettle RP, Gore SM. Mortality from overdose among injecting drug users recently released from prison: database linkage study. BMJ. 1998;316:426–428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeev B, Karpets A, Sarang A, Tikhonov M. Prevalence and circumstances of opiate overdose among injection drug users in the Russian Federation. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80:212–219. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton N, Pendry E, Taylor C, Farrell M, Marsden J. Drug-related mortality among newly released offenders. London: UK Home Office; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, Woolard J. Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1764–1778. doi: 10.1037/a0012955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart L, Henderson C, Hobbs MST, Ridout SC, Knuiman MW. Risk of death in prisoners after release from jail. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2004;28:32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz JA, Wood E, Small W, Li K, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG, et al. Changes in injecting practices associated with the use of a medically supervised safer injection facility. Journal of Public Health. 2007;29:35–39. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoové MA, Dietze PM, Jolley D. Overdose deaths following previous non-fatal heroin overdose: Record linkage of ambulance attendance and death registry data. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28:347–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J. Looking beyond death: Paying attention to other important consequences of heroin overdose. Addiction. 2002;97:927–928. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, Beswick T, Bearn J, Rees S, et al. Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: Follow up study. BMJ. 2003;326:959–961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7396.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin KE, Hua W, Costenbader EC, Latkin CA. The association between change in social network characteristics and non-fatal overdose: Results from the SHIELD study in Baltimore, MD, USA. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman SE, Bowman SE, McKenzie M, Jeronimo A, Rich JD. Preventing death among the recently incarcerated: An argument for naloxone prescription before release. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2009;28:124–129. doi: 10.1080/10550880902772423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, White MC, Jamison R, Goldenson J, Estes M, Tulsky JP. Discharge planning and continuity of health care: Findings from the San Fransisco county jail. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:2182–2184. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner-Smith M, Darke S, Day C. Morbidity associated with non-fatal heroin overdose. Addiction. 2002;97:963–967. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner-Smith M, Darke S, Lynskey M, Hall W. Heroin overdose: Causes and consequences. Addiction. 2001;96:1113–1125. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Prevention of acute drug-related mortality in prison populations during the immediate post-release period. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Qin GM, Ruan YH, Qian HZ, Hao C, Xie LZ, et al. Nonfatal overdose among heroin users in southwestern China. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:505–516. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]