ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Obesity is a stigmatizing condition associated with adverse psychosocial consequences. The relative importance of weight stigma in reducing health utility or the value a person places on their current health state is unknown.

METHODS

We conducted a telephone survey of patients with obesity. All were seeking weight loss surgery at two bariatric centers (70 % response rate). We assessed patients’ health utility (preference-based quality life measure) via a series of standard gamble scenarios assessing patients’ willingness to risk death to lose various amounts of weight or achieve perfect health (range 0 to 1; 0 = death and 1 = most valued health/weight state). Multivariable models assessed associations among quality of life domains from the Short-form 36 (SF-36) and Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-lite (IWQOL-lite) and patients’ health utility.

RESULTS

Our study sample (n = 574) had a mean body mass index of 46.5 kg/m2 and a mean health utility of 0.87, reflecting the group’s average willingness to accept a 13 % risk of death to achieve their most desired health/weight state; utilities were highly variable, however, with 10 % reporting a utility of 1.00 and 27 % reporting a utility lower than 0.90. Among the IWQOL-lite subscales, Public Distress and Work Life were the only two subscales significantly associated with patients’ utility after adjustment for sociodemographic factors. Among the SF-36 subscales, Role Physical, Physical Functioning, and Role Emotional were significantly associated with patients’ utility. When the leading subscales on both IWQOL-lite and SF-36 were considered together, Role Physical, Public Distress, and to a lesser degree Role Emotional remained independently associated with patients’ health utility.

CONCLUSION

Patients seeking weight loss surgery report health utilities similar to those reported for people living with diabetes or with laryngeal cancer; however, utility values varied widely with more than a quarter of patients willing to accept more than a 10 % risk of death to achieve their most valued health/weight state. Interference with role functioning due to physical limitations and obesity-related social stigma were strong determinants of reduced health utility.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity prevalence has risen substantially recently and afflicts 34 % of US adults.1–5 Obesity has substantial physical, social, and economic consequences that negatively affect quality of life (QOL).6,7 Between 2003 and 2008, over 100,000 obese patients underwent weight loss surgery each year to mitigate the complications of obesity.8

Unlike many chronic health conditions, obesity impairs QOL not only because of its health burden but also because obesity, in many cultures, is socially undesirable and stigmatizing.9 Obese persons are targets of bias in arenas such as education, employment, socialization, and healthcare treatment.9 Given this, persons with obesity often report lower QOL in terms of self-esteem, sexual functioning, work life, and public distress in addition to the more traditional domains of physical functioning.7,10–13 It is unclear, however, whether obesity’s stigma and adverse psychosocial consequences are as, if not more, detrimental to overall QOL than more traditional QOL measures of physical and mental functioning. Identifying the factors that are particularly important in driving diminished overall QOL may provide insight into what motivates obese patients to seek weight treatment. It also allows us to identify the most relevant QOL outcome targets in gauging the overall effectiveness and value of weight control interventions from the patients’ perspective.

Many studies have used health status surveys to capture QOL. Such surveys capture the aspects of QOL that are affected by a condition but do not allow conclusions to be drawn about the relative importance of each domain from the patient’s perspective. The gold standard approach to assessing patient preferences for various health states is to measure their health utility.14 Utilities are valuations that an individual assigns to either his or her current health or another health outcome that represents the strength of his or her preference for specific health-related outcomes. This method has the advantage of allowing patients to consider all factors important to them in making their value judgment rather than estimating QOL based on a pre-specified spectrum of domains. However, it cannot tell you what aspects of QOL led to the devaluation of a particular health state.

In this context, we interviewed over 570 patients seeking weight loss surgery and studied the relationship between different aspects of their QOL as measured by health status surveys and patients’ overall health utility. In doing so, we were able to evaluate the relative importance of different QOL domains in contributing to diminished overall QOL from the patients’ perspective. We hypothesized that weight stigma was as important as, if not more important than, other domains based on its relationship with health utility.

METHODS

Study Sample, Recruitment, and Data Collection

We recruited patients who were being evaluated for weight loss surgery at two academic medical centers in Boston, one of which serves a large racial minority and socially disadvantaged urban population. To be eligible, patients had to speak English, be aged 18 to 65, and have a valid address and phone number. Patients were excluded if they had undergone weight loss surgery or were excluded by their health providers.

Our study was approved by institutional review boards (IRB) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston Medical Center, and University of Massachusetts Center for Survey Research (all in Boston, MA). Consecutive subjects who were potentially eligible were identified via appointment logs. At the first site, potentially eligible subjects were recruited either via mail and/or in-person at their clinical visit. Those who expressed interest were then contacted by phone, and verbal consent was obtained by trained interviewers at the University of Massachusetts Center for Survey Research; of 615 eligible patients at the first site, 432 enrolled (70 % response rate). At the second site, of 421 potentially eligible patients, 104 underwent surgery before we could approach them, and 222 enrolled (70 % response rate). There were no statistically significant differences between participants and eligible nonparticipants by sex or race; however, non-participants were slightly younger (42 vs 44 years of age, p = 0.006).

Both groups underwent a 45–60-min telephone interview prior to surgery that elicited their demographic information, self-reported height and weight, quality of life (QOL), and preferences for current health and weight relative to perfect health and different levels of weight loss. Patients were compensated $50 for their time. Interviews were conducted by experienced interviewers who were trained in standardized interviewing techniques. Interviews were scripted and questions written with the goal of minimizing extraneous interviewer-respondent interactions that lead to interviewer effects or respondent bias.

Health Utility

We assessed patients’ preference or “utility” for their current weight and health using an adapted version of the standard gamble method. Respondents were asked to consider a hypothetical choice: the certainty of continuing in their current health and weight or taking a gamble. The gamble has two possible outcomes: the positive outcome of “perfect health” and a negative outcome of immediate death. Because we were particularly interested in the value patients placed on varying degrees of lower weight in addition to perfect health, we administered a series of additional scenarios. We asked patients to envision a treatment that would produce a permanent weight loss of a specified amount that required no effort on their part and would produce no side effects. We then specified that the treatment was associated with a small risk of death, and through an iterative process, we asked patients to estimate the highest risk of dying they were willing to accept in order to achieve each weight outcome. The specified weight loss expressed in pounds was, in order of presentation, patients’ self-reported “ideal” weight, weight loss associated with a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2, or patients’ “highest healthy weight,” 20 % weight loss, and 10 % weight loss. We asked patients to consider these scenarios in the context of living in their current weight and to assume that there were no other available weight loss treatments either now or in the future except for the proposed treatment.

Using their responses to these scenarios, we calculated patients’ utility for their current state making no preconceived assumptions about what their most valued health state should be, as our prior work found some patients value weight loss more than achieving the traditional reference state of “perfect health.”15 The health/weight state of highest value to the patient (i.e., the outcome for which the patient was willing to accept the highest risk of dying) served as the reference state with an assigned utility of 1.00. For example, if a patient responds that he/she is willing to accept a risk of 10 % for a given health/weight state, then he/she is calculated to have a current health utility of 0.90.

Other Qualify of Life Measures

We also assessed QOL using the Short-form-36 Health Survey (SF-36)16 and the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-lite (IWQOL-lite).10 The SF-36 is a 36-item, widely validated general measure of health-related QOL.16 It captures eight domains or subscales and is scored on a 0–100 scale for each subscale.16 All scores were standardized to the general US population so that a score of 50 is considered normative.

The IWQOL-lite is a 31-item instrument developed to capture 5 domains specific to obesity10—physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress, and work. Respondents are given a series of statements that begin with “Because of my weight…” and then asked to rate whether the statement is “always true, usually true, sometimes true, rarely true, or never true.” For example, the Public Distress subscale asks whether the respondent experiences ridicule, teasing, or unwanted attention because of their weight, whether they worry about fitting into seats in public places, fit into aisles, finding chairs that are strong enough, etc., and whether they experience discrimination. This subscale has been shown to have construct validity for capturing “weight stigma.”10,11 The IWQOL-lite is also scored on a 0–100 scale for each subscale7; it has excellent psychometric properties and test-retest reliability.10 Higher scores reflect better QOL but scores are not normalized to the US population.

Data Analysis

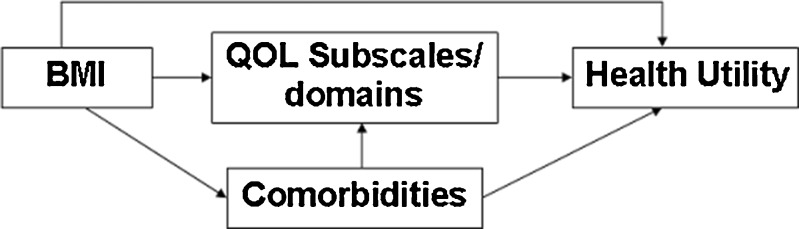

To identify which obesity-related QOL consequences were most associated with patients’ disutility for being obese, we modeled the relationship between different QOL domains (subscales) and patients’ current utility. Models were adjusted for patient’s age, sex, race and ethnicity, and study site. We did not adjust for BMI or comorbidities in our primary analyses because both are upstream in the causal pathway and are highly correlated with QOL (see Fig. 1); adjusting for these factors may therefore lead to overadjustment and mask the full association between an individual QOL domain and health utility.

Fig. 1.

Causal diagram of the interrelationship between BMI, obesity-related comorbidities, quality of life (QOL), and health utility

We first considered the five domains assessed by the IWQOL-lite using a forward selection process retaining subscales that were statistically significantly associated with health utility in our final model. To establish the rank order in which subscales would be introduced during the forward selection process, we first examined the relationship of each subscale and health utility individually in separate models. We then ranked the contribution of each subscale based on the adjusted model R2 or the change in model coefficient of determination. The model R2 ranges up to 1.00 and can be interpreted as the proportion of the variability in outcome measured by variables in the model. Individual subscales with higher adjusted model R2 were added first in our forward selection process. We present adjusted model R2s from these sequential models to estimate the marginal contribution of each additional subscale in explaining the absolute variation in outcome relative to the preceding model. Our final model retained all subscales significantly associated with our outcome with a p-value <0.05. Using a similar approach, we examined the individual and combined relationship among the scores from eight subscales comprising the SF-36 and patients’ utility. Because utility scores were highly skewed, we also repeated these analyses using logistic regression redefining our outcome as a dichotomous variable. Those with high utility were defined as having a utility of 0.90 or higher; 27 % of our study sample had a utility of less than 0.90.

RESULTS

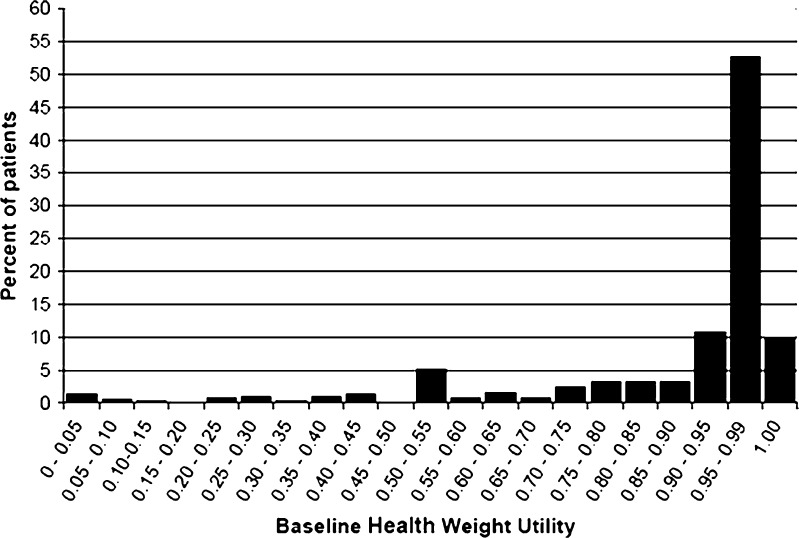

Table 1 characterizes 574 of 654 patients enrolled in our study who had complete data on relevant demographic, quality of life, and utility preference measures; 42 excluded patients had missing utilities values, and 35 had missing values for quality of life variables. Excluded patients did not differ by race, BMI, or educational status but were slightly older (mean age 48 years) and were more likely to be female (88 %). The mean perceived life expectancy was 21 years, and the median was 20 years. The mean utility score among our study sample was 0.87, reflecting patients’ average willingness to accept a 13 % risk of dying to achieve their preferred weight/heath state. However, the median value was 0.97, reflecting the skewed distribution in utility scores (see Fig. 2).17 Table 2 presents mean utilities scores of patients in our study according to BMI categories and to specific obesity-related comorbidities. For the most part, utilities were lower for those with specific comorbid conditions than among patients without that particular comorbidity.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 574)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 43.5 ± 11.7 |

| Weight in lbs (BMI in kg/m2), mean ± SD | 291.0 ± 61.2 (46.5 ± 7.7) |

| Sex | |

| Female, % | 73.3 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |

| White | 67.7 |

| African American | 17.6 |

| Hispanic | 11.7 |

| Education, % | |

| HS diploma, GED, or less | 26.3 |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 37.5 |

| 4-year college diploma or higher | 36.2 |

| Perceived life expectancy in years | |

| Mean ± SD | 21.4 ± 14.0 |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 20 (10, 30) |

| Utility for current weight and health | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.87 ± 0.22 |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 0.97 (0.85, 0.999) |

| IWQOL-lite score, mean ± SD | |

| Overall summary | 53.8 ± 19.7 |

| SF-36 score, mean ± SD | |

| Physical component summary | 38.0 ± 10.3 |

| Mental component summary | 49.4 ± 11.2 |

Fig. 2.

Distribution of current health/weight utility among patients seeking weight loss surgery

Table 2.

Utility for Current Weight and Health Across Baseline BMI Categories and Comorbidities

| Sample size (%) | Mean ± SD | Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | |||

| 35.0–39.9 | 88 (15) | 0.85 ± 0.24 | 0.97 (0.83, 0.99) |

| 40.0–44.9 | 209 (36) | 0.90 ± 0.20 | 0.99 (0.90, 0.99) |

| 50.0–54.9 | 128 (22) | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.99 (0.85, 0.99) |

| 55.0 + | 149 (26) | 0.83 ± 0.24 | 0.95 (0.75, 0.99) |

| Heart disease/congestive heart failure/cardiomyopathy/peripheral vascular disease | |||

| Yes | 41 (7) | 0.75 ± 0.30 | 0.90 (0.50, 0.99) |

| No | 533 (93) | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.98 (0.87, 0.99) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | |||

| Yes | 266 (46) | 0.86 ± 0.22 | 0.96 (0.80, 0.99) |

| No | 308 (54) | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.99 (0.89, 0.99) |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 303 (53) | 0.86 ± 0.22 | 0.97 (0.80, 0.99) |

| No | 271 (47) | 0.88 ± 0.22 | 0.98 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 184 (32) | 0.84 ± 0.23 | 0.95 (0.75, 0.99) |

| No | 390 (68) | 0.88 ± 0.22 | 0.98 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Asthma | |||

| Yes | 143 (25) | 0.86 ± 0.24 | 0.99 (0.85, 0.99) |

| No | 431 (75) | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.97 (0.85, 0.99) |

| GERD/esophagitis/Barrett’s | |||

| Yes | 258 (45) | 0.85 ± 0.23 | 0.97 (0.80, 0.99) |

| No | 316 (55) | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.98 (0.90, 0.99) |

| Arthritis or chronic back pain | |||

| Yes | 371 (41) | 0.87 ± 0.23 | 0.98 (0.85, 0.99) |

| No | 533 (59) | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.98 (0.86, 0.99) |

| Liver disease | |||

| Yes | 275 (48) | 0.86 ± 0.22 | 0.96 (0.80, 0.99) |

| No | 299 (52) | 0.88 ± 0.22 | 0.99 (0.89, 0.99) |

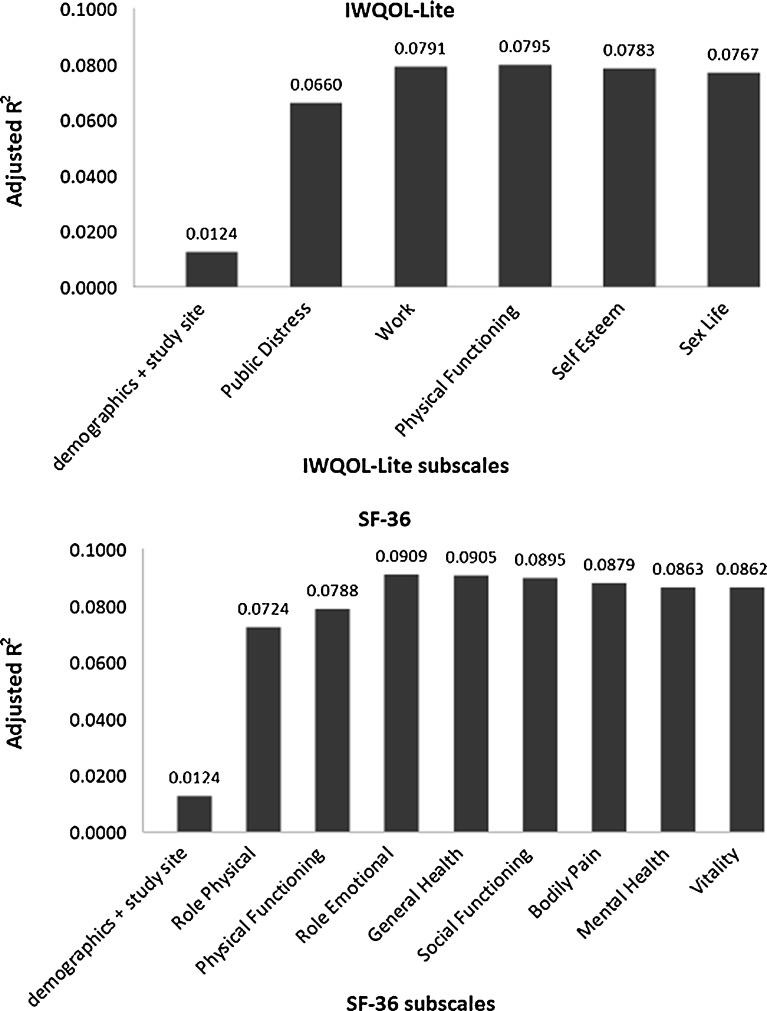

Of domains measured on the IWQOL-lite, patients’ level of public distress about their weight and the work life subscale contributed to the highest model R2, indicating that they explained the largest variability in patient utility relative to the other subscales. (Table 3) Among domains measured by SF-36, role limitations due to impairment in physical health (Role Physical subscale) had the highest model R2.

Table 3.

Contribution of Individual Quality of Life Domains in Explaining Variability in Patients’ Current Utility in Order of Importance (n = 574)*

| Mean score in study sample | Adjusted model R2†, primary model | Adjusted model R2‡, adjusted for comorbidty | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IWQOL-lite subscales | |||

| Public distress | 46.7 ± 22.9 | 0.066 | 0.085 |

| Work life | 48.4 ± 26.2 | 0.066 | 0.081 |

| Physical function | 65.9 ± 30.0 | 0.055 | 0.075 |

| Self-esteem | 57.7 ± 25.7 | 0.044 | 0.067 |

| Sex life | 65.9 ± 24.3 | 0.033 | 0.056 |

| SF-36 subscales | |||

| Role physical | 36.4 ± 10.3 | 0.072 | 0.087 |

| Physical functioning | 42.2 ± 10.2 | 0.063 | 0.082 |

| Role emotional | 47.2 ± 10.7 | 0.060 | 0.081 |

| General health | 45.3 ± 11.4 | 0.050 | 0.069 |

| Social functioning | 43.0 ± 10.6 | 0.048 | 0.067 |

| Bodily pain | 40.5 ± 10.1 | 0.043 | 0.063 |

| Mental health | 46.9 ± 10.4 | 0.041 | 0.064 |

| Vitality | 43.5 ± 9.7 | 0.034 | 0.058 |

*The adjusted Model R2 refers to the proportion in variability of the outcomes explained by the model

†Models contain the individual subscale and are adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and study site

‡Models contain the individual subscale and are adjusted for age, sex, race, education, study site, BMI, heart disease/congestive heart/cardiomiopathy/peripheral vascular disease and leukemia/polycythemia vera, lymphoma/other non-skin CA/AIDS

Figure 2 shows the degree to which individual subscales explained the variability in utility when subscales were considered sequentially, beginning with subscales with the highest adjusted model R2 shown in Table 3. Of those subscales comprising the IWQOL-lite, patients’ level of public distress was the strongest correlate and accounted for an additional 5.4 % of the variation in patients’ utility beyond the 1.2 % explained by demographic factors and study site alone (Fig. 3). A 10-point decrease in the Public Distress score (reduction in distress level) was associated with a reduction in utility of 0.013 (Table 4). Adding patients’ level of work functioning only improved the model’s explanatory ability by 1.3 %. Adding other IWQOL-lite subscales did not improve the proportion of variation explained. Our results were consistent when we adjusted for BMI and comorbidities. Both Public Distress and Work subscales emerged as leading correlates when we repeated our primary analyses using logistic regression with our outcome redefined as whether patients had a health utility of 0.90 or higher (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Marginal contributions of individual subscales in explaining the variation in patients’ health utility, after adjustment for the number of factors in the model. The first model (bar labeled “demographic + study site”) includes age, sex, race, education and study site only. All subsequent models include the subscale listed in addition to the variables in the preceding model

Table 4.

Quality of Life Subscales Independently Associated with Patients’ Current Utility*

| Δ utility per 10 points | Δ utility per 10 points | Δ utility per 10 points | Δ utility per 10 points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ score among IWQOL-lite subscales | Δ score among SF-36 subscales | Δ score among IWQOL/SF-36 subscales considered together | Δ score among IWQOL/SF-36 subscales adj. for BMI and comorbidity† | |

| IWQOL-lite | ||||

| Public distress | 0.013, p = 0.003 | – | 0.013, p = 0.0012 | 0.013, p = 0.02 |

| Work life | 0.014, p = 0.002 | – | NS | NS |

| SF-36 | ||||

| Role physical | – | 0.027, p = 0.03 | 0.032, p = 0.0030 | 0.023, p = 0.08 |

| Physical functioning | – | 0.024, p = 0.05 | NS | NS |

| Role emotional | – | 0.028, p = 0.004 | 0.024, p = 0.0115 | 0.022, p = 0.02 |

| Adjusted model R2 | 0.0791 | 0.0909 | 0.1016 | 0.1125 |

*Parameter estimates are associated with a change in subscale of 10 points, e.g., a 10-point increase in score on the Public Distress subscale (reduction in distress) is associated with a 0.013 increase in weight-based utility (better quality of life). All models are adjusted for age, sex, race, education, and study site. NS indicates nonsignificant subscales when domains from both the IWQOL-lite and SF-36 are considered together. “–“ indicates the subscale was not tested for inclusion into the model

†Analyses further adjusted for BMI and comorbidities (CAD/heart disease, MI, CHF/cardiomyopathy, PVD, and leukemia/polycythemia vera, lymphoma, other non-skin CA, and AIDS)

Of the subscales from the SF-36, role limitations due to physical health (Role Physical subscale) was the most important correlate of patients’ utility, explaining 6 % of the variation (Fig. 3). A 10-point increase in score was associated with a 0.027 increase in utility. Other significant correlates were patients’ reported physical functioning and their role limitations due to mental health impairments (Role Emotional subscale) although their added contributions were modest. Our results were consistent when we adjusted for BMI and comorbidities. Both Role Physical and Physical Functioning subscales also emerged as leading correlates when we repeated our primary analyses using logistic regression with our outcome redefined as whether patients had a health utility of 0.90 or higher (data not shown).

In post hoc analyses, we explored the relative contribution of the statistically significant subscale correlates with the highest model R2 from both the IWQOL-lite (Public Distress and Work Life) and SF-36 (Role Function, Physical Function, and Role Emotional) (see Table 4). Role Physical, Public Distress, and Role Emotional subscales remained significantly associated with patients’ current utility; Role Physical (first added to the model) contributed 6 % of the variation, and Public Distress contributed an additional 2.1 %, whereas Role Emotional contributed only 0.9 %. Every 10-point increase in Role Physical score was associated with a 0.032 rise in utility; a 10-point rise in Public Distress is associated with a 0.013 rise in utility. Public Distress and Role Physical also emerged as the two leading domains in sensitivity analyses where the outcome was redefined as having a utility score of 0.90 or higher. When we stratified our analyses by BMI, we found that our results were replicated among those with a BMI of 45 or higher. However, among those with lower BMI, self-esteem (IWQOL-lite) and physical functioning (SF-36) were the only two subscales that were significantly correlated with health utility, suggesting that obese individuals with different levels of obesity may value different domains of quality of life.

COMMENT

In our study of over 570 obese patients seeking weight loss surgery, patients reported a mean health utility of 0.87 for living at their current health and weight, indicating that on average patients were willing to accept a 13 % risk of dying to achieve their preferred health or weight state. Utilities were highly variable, however, with 10 % of patients reporting a utility of 1.0 and more than a quarter of patients reporting a utility of less than 0.90. Of the quality of life (QOL) domains assessed in our study, physical limitations that interfered with role functioning and the public distress of being obese (measure of social stigma) were the two most important aspects of QOL associated with having low health utility. Other domains that were typically associated with obesity—poor physical, emotional and social functioning, low self-esteem, bodily pain, poor sexual functioning, and low vitality—did not explain much of the variation in patients’ reported utility or overall QOL.

Previous studies have documented that overall QOL is substantially diminished among patients with obesity and that most QOL domains measured are adversely affected. Compared to normal weight persons, obese patients who seek weight treatment report worse scores on all five subscales of the IWQOL-lite.18 Other studies show a strong association between overall physical functioning on the SF-36 and BMI.13,19 These survey studies cannot distinguish, however, the QOL domains that have the greatest impact on or are most important to patients.

The gold standard approach of measuring patient preferences for different outcomes or health states is to assess health utility, which has been estimated for numerous other health conditions.14,20 The utility assigned to current weight of 0.87 among obese patients in our study is similar to utilities assigned to living with diabetes or laryngeal cancer in other studies.20 Patients in our study who also had diabetes reported even lower utilities than patients without diabetes, reflecting the added disutility of having diabetes along with severe obesity. Our group previously documented average utilities of 0.88 among 100 obese primary care patients and 0.92 among 44 patients seeking weight loss surgery although the reference states used were slightly different from the ones in our current study.15,21 A few other studies have estimated substantially lower utilities among obese patients; however, none of these studies assessed utilities directly but rather by extrapolation and so are not comparable to the direct utility measurements we report.22–24

By examining the relationship between various QOL domains and patient-reported utilities, our study was able to identify aspects of QOL most correlated with what patients value. For example, a 10-point increase in the Role Physical subscale, which is equivalent to the difference in the average scores observed in someone in their 50s relative to someone in their 60s, was associated with a utility increase of 0.03.25 In contrast, a 10-point increase in the Public Distress subscale, which is observed with a 10 % weight loss, was associated with a 0.01 increase health utility score in our study.26 It is important to note that our QOL measures only explained a relatively small proportion of the variation in a person’s health utility. Interestingly, the addition of demographic factors, BMI, and comorbid conditions did not improve our model’s performance substantially.

Our findings are provocative in several ways. First it suggests that the public distress or social stigma associated with obesity is one of the most important factors contributing to diminished QOL among patients with obesity, especially those with severe obesity. Work by our group27,28 and others29 suggests that weight stigma not only has an adverse effect on obese individuals psychosocially but may also lead some obese persons to avoid needed healthcare, which ultimately has direct medical implications. Weight stigma is not inherent to obesity but rather a reflection of societal values and bias. As such, it could be potentially addressed through nontraditional approaches to improving health including efforts to reduce weight bias. Second, our results raise questions about whether we are examining and considering the most appropriate QOL outcome targets in our assessment of various weight control interventions. Most studies of weight loss interventions assess changes in overall QOL summary scores without distinguishing the QOL domains most responsible for reducing overall QOL or that are most relevant to patients. Finally, our findings suggest that the outcomes that are most often valued by clinicians and policy makers are not always the only or even most important outcomes valued by patients.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. Study subjects were recruited from two academic weight loss surgery centers and may not generalize to all obese patients or even all patients seeking weight loss treatment. Only about 1 % of eligible US adults actually undergo weight loss surgery.30 Our findings likely reflect those most adversely affected by their obesity. Secondly, our research demonstrates associations and we cannot necessarily infer a causal link between weight stigma or impaired role functioning and low health utility, nor can we conclude that improvements in either weight stigma or impaired role functioning will necessarily improve patients’ health utility; this link will need to be established in future studies that prospectively measure changes in these domains and changes in health utility as a result of weight loss. While they appear to be the primary drivers of lower utility among the domains we studied, we also cannot conclude that public distress and impaired role functioning from physical impairments are the determinants of patients’ decisions to seek weight loss surgery, especially when we have not compared these findings to those of a control group of patients who choose not to seek weight loss surgery. Finally, our results are influenced by how QOL domains were measured. One domain can appear to be more important than a second domain if the second domain is not as well measured as the first.

In summary, patients seeking weight loss surgery report health utilities similar to those living with serious chronic conditions. Two strong quality of life (QOL) determinants of disutility among obese patients were the interference of role functioning due to physical limitations and the public distress or social stigma associated with being obese. Studies examining the impact of weight loss on QOL should not only focus on QOL summary scores but should also give special consideration to the aspects of QOL most relevant to patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK073302). Dr. Wee is also supported by a midcareer mentorship award from the National Institute of Health (K24DK087932). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Wee conceived the research question, designed the study, obtained funding, supervised the conduct of the study, and drafted the manuscript. Drs. Jones and Wee facilitated the collection of the data. Ms. Huskey had full access to all the data, conducted all the analyses, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Davis provided statistical expertise and along with Drs. Hamel and Wee interpreted the data. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. We thank the patients for participating in our study and thank the ABS study team for their efforts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flegal KM, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed]

- 3.Calle EE, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick HE, et al. Differential effects of BMI on diabetes risk among black and white Americans. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(11):1828–35. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.11.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens J. Impact of age on associations between weight and mortality. Nutr Rev. 2000;58(5):129–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2000.tb01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(12):788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White MA, et al. Gender, race, and obesity-related quality of life at extreme levels of obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12(6):949–55. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen NT, et al. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003–2008. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(2):261–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1019–28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolotkin RL, et al. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9(2):102–11. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolotkin RL, et al. Assessing impact of weight on quality of life. Obes Res. 1995;3(1):49–56. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadden TA, Phelan S. Assessment of quality of life in obese individuals. Obes Res. 2002;10(Suppl 1):50S–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wee CC, Davis RB, Hamel MB. Comparing the SF-12 and SF-36 health status questionnaires in patients with and without obesity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell LB, et al. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 1996;276(14):1172–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540140060028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wee CC, et al. Understanding patients’ value of weight loss and expectations for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16(4):496–500. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version two of the SF-36 health survey. QualityMetric Incorporated: 2000.

- 17.Wee CC, et al. Expectations for weight loss and willingness to accept risk among patients seeking weight loss surgery. Arch Surg. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD. Psychometric evaluation of the impact of weight on quality of life-lite questionnaire (IWQOL-lite) in a community sample. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(2):157–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1015081805439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corica F, et al. Construct validity of the Short Form-36 Health Survey and its relationship with BMI in obese outpatients. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(8):1429–37. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tengs TO, Wallace A. One thousand health-related quality-of-life estimates. Med Care. 2000;38(6):583–637. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wee CC, et al. Assessing the value of weight loss among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1206–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon S, Currie CJ, McEwan P. Utility values for obesity and preliminary analysis of the Health Outcomes Data Repository. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004;4(6):657–65. doi: 10.1586/14737167.4.6.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakim Z, Wolf A, Garrison LP. Estimating the effect of changes in body mass index on health state preferences. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20(6):393–404. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200220060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groessl EJ, et al. Body mass index and quality of well-being in a community of older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(2):126–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware JE. SF-36 Health Survey. Boston, MA: Manual & Interpretaion Guide; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolotkin RL, et al. One-year health-related quality of life outcomes in weight loss trial participants: comparison of three measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wee CC, et al. Screening for cervical and breast cancer: is obesity an unrecognized barrier to preventive care? Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):697–704. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wee CC, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. BMI and cervical cancer screening among white, African-American, and Hispanic women in the United States. Obes Res. 2005;13(7):1275–80. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drury CA, Louis M. Exploring the association between body weight, stigma of obesity, and health care avoidance. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(12):554–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinbrook R. Surgery for severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1075–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]