ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Readmission and mortality after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and heart failure (HF) are publically reported. This systematic review assessed the impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality after hospitalization for CAP and HF—variables outside a hospital’s control.

METHODS

We searched OVID, PubMed and PSYCHINFO for studies from 1980 to 2012. Eligible articles examined the association between social factors and readmission or mortality in patients hospitalized with CAP or HF. We abstracted data on study characteristics, domains of social factors examined, and presence and magnitude of associations.

RESULTS

Seventy-two articles met inclusion criteria (20 CAP, 52 HF). Most CAP studies evaluated age, gender, and race and found older age and non-White race were associated with worse outcomes. The results for gender were mixed. Few studies assessed higher level social factors, but those examined were often, but inconsistently, significantly associated with readmissions after CAP, including lower education, low income, and unemployment, and with mortality after CAP, including low income. For HF, older age was associated with worse outcomes and results for gender were mixed. Non-Whites had more readmissions after HF but decreased mortality. Again, higher level social factors were less frequently studied, but those examined were often, but inconsistently, significantly associated with readmissions, including low socioeconomic status (Medicaid insurance, low income), living situation (home stability rural address), lack of social support, being unmarried and risk behaviors (smoking, cocaine use and medical/visit non-adherence). Similar findings were observed for factors associated with mortality after HF, along with psychiatric comorbidities, lack of home resources and greater distance to hospital.

CONCLUSIONS

A broad range of social factors affect the risk of post-discharge readmission and mortality in CAP and HF. Future research on adverse events after discharge should study social determinants of health.

KEY WORDS: readmission, mortality, systematic review, heart failure, community acquired pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Policy makers have identified rates of readmission and mortality within 30 days after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and heart failure (HF) as indicators of quality and coordination of care.1 While the risk of 30-day readmission and mortality would be expected to be influenced by inadequate inpatient care and discharge planning, many other patient factors likely contribute to poor outcomes. However, most risk models designed to predict readmission and mortality do not include social factors.2 The models developed by Krumholz et al.3–6 that are used by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) to profile hospitals control for disease severity, comorbidity, age and gender. According to Andersen’s behavioral model,7 many different aspects of a patient’s social, behavioral, and environmental milieu could likely influence post-discharge outcomes through several different mechanisms. In fact, several studies have found that many different domains of social disadvantage may influence post-hospital outcomes in CAP and HF, such as: sociodemographics,8,9 insurance,10–12 social support,13 adherence,14 and substance abuse,12 among others.

While prior systematic reviews have been done on predictors of readmission or mortality,2,15,16 their focus has been primarily on the adequacy of adjustment for clinical factors such as disease severity and comorbidities or simple sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race). While clinicians, social workers, and case managers are well aware of the broad range of social factors that contribute to patients doing poorly after hospital discharge, no systematic review to date has sought to examine the evidence base behind this commonly held belief. The extent to which a broad range of measures of social disadvantage not within a hospital’s or health system’s control substantially influences post-discharge outcomes has important implications for clinicians, researchers, and policy makers.

The goals of this systematic review were to: 1.) identify and categorize the general domains of social factors that could influence post-discharge outcomes; and 2.) summarize the presence and magnitude of reported associations between social factors and risk of readmission or mortality in CAP and HF.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Study Selection

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid PsycINFO, and PubMed studies published between January 1, 1980 and April 2012. Eligible articles needed to: 1) report risk of readmission and/or 30 day risk of mortality, 2) measure at least one social factor in patients hospitalized with CAP or HF, 3) have the opportunity to examine an association between risk of readmission or 30-day risk of mortality and at least one social factor, and 4) be published in a peer-reviewed English-language journal. Since our focus was community-acquired pneumonia, we excluded HIV-associated pneumonia, nosocomial and nursing home-acquired pneumonia. We excluded case series, case reports, and reviews.

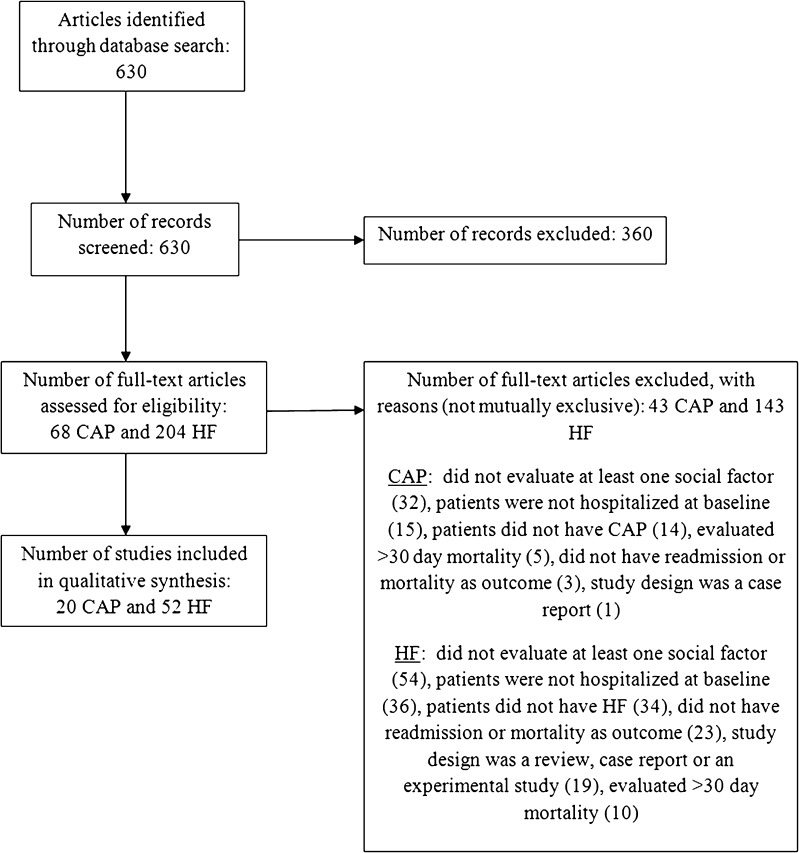

Our search strategy had several components (See Fig. 1 for details). First, we used the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: “readmission” and “mortality” (exploded and truncated “readmi*” and “rehosp*”), “risk” (exploded), “model*”, “predict*”, “use*”, “util*”, “risk*”, “heart failure” and “pneumonia”. Second, because we were interested in a range of social factors, we cast a wide net with MeSH terms (exploded) for: “sociology, insurance, homeless persons, mental disorders, street drugs, drinking behavior, smoking, health behavior, social psychology, health status, population dynamics, residence characteristics, sex distribution, health, population, family characteristics, socioeconomic factors, population characteristics, demography, age distribution, censuses, ethnic groups, population density, and population groups”. We limited the search to humans, English language, and adults. The intersection of all of these searches identified 630 studies for review. Application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria yielded a total of 72 articles (20 CAP and 52 HF) in our final review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic review strategy and outcomes.

Data Collection Process

These 20 CAP and 52 HF articles were reviewed in detail and abstracted by two investigators using a modified version of a previously published abstraction tool.17 Data abstracted from each publication included: funding source, purpose, design, time period, data source, method of identifying cases, number of hospitals, hospital geographic location, statistical strategy, sample size, follow-up period, type of readmission or mortality (all-cause or disease specific), number of readmissions per patient included, and whether mortality was considered a separate or composite outcome. The type of statistical association (univariate or multivariate) between social factors and readmission or mortality was abstracted. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, or a third reviewer if necessary.

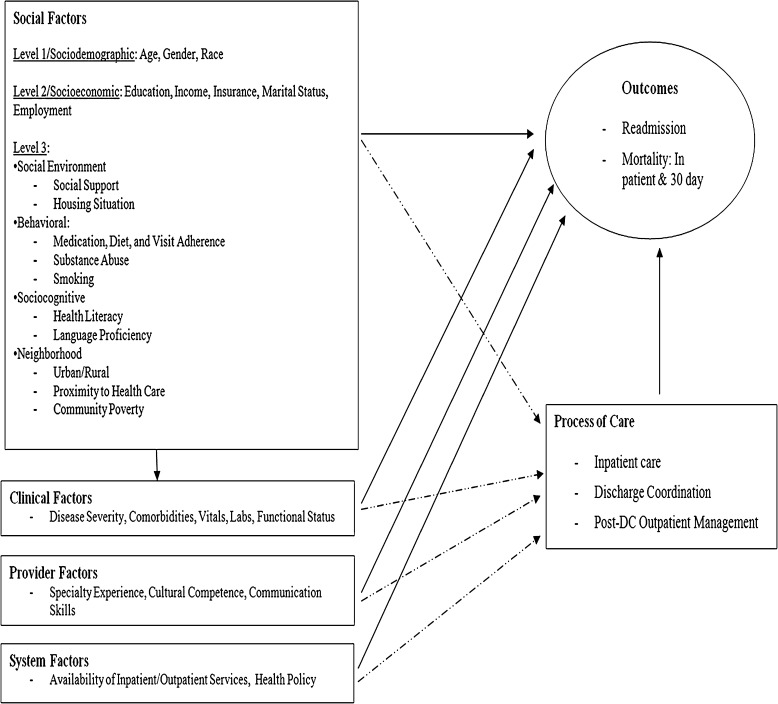

Conceptual Model of Social Factors

Because the notion of what ought to be considered a social factor is a complicated judgment, we constructed a conceptual model (See Fig. 2) outlining the diverse range of domains that could influence post-discharge outcomes, based on a review of the literature and consultation with experts in the field. We stratified social factors into three levels based on ease of measurement and mechanistic potential to directly influence post-discharge outcomes.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of how social factors may influence readmissions and mortality.

We classified simple sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, and race which are readily ascertained from most administrative databases as Level 1 factors. Level 2 factors included socioeconomic variables, such as education, employment, income, insurance, and marital status, that often require some type of additional data collection strategy (patient interview, medical record abstraction). Level 3 factors were those that relate to underlying social environment (social support, housing situation), behavioral (medication, diet, visit adherence, substance use/abuse, smoking), socio-cognitive (health literacy, language proficiency), and neighborhood (urban/rural, proximity to health care, community poverty) attributes that may more directly influence health and health care. These types of social factors usually require a more resource intensive and/or deliberate data collection strategy to be measured (patient interview, medical record abstraction, geospatial databases). For example, Amarasingham et al.12 showed the independent prognostic value of accounting for these higher level social factors in predicting the 30-day risk of readmission and mortality in HF. A review by Kansagara et al.2 critiquing existing predictive models of readmissions highlighted that while several models included Level 1 social factors, few included Level 2 or 3 factors.

To be inclusive, our conceptual model used a broad definition of social factors that included neighborhood characteristics and highlighted the direct impact that social factors have on process of care and outcomes. Prior models have Level 3 social factors functioning as enabling factors between demographics and outcomes,7 or have a hierarchical approach18 to outcomes.

RESULTS

Study Selection

A total of 72 (20 CAP and 52 HF) candidate articles met our inclusion criteria and were included in our final review. A PRISMA flow diagram outlining the details of the systematic review is shown in Figure 1. The most common reasons for exclusion of candidate articles were because no social factors were evaluated, or patients were not hospitalized for the condition of interest.

Characteristics of Included Studies

The included studies varied greatly in primary purpose, design, and analytic approaches, making formal synthesis not possible. Tables 1 and 2 display the details of the included CAP and HF articles respectively. For CAP, there were 17 retrospective studies and one prospective cohort study, one cross-sectional, and one nested within a randomized control trial of an intervention. Among the 20 CAP studies, 11 were based solely on administrative data, six used a combination of administrative database and medical record review or interviews, and only three were based on directly collected social factor data from the medical record and/or interviews. Sixteen studies were based on multicenter data and four were done as single sites. The sample size for CAP studies ranged from 71 to 8,958,337 with a median of 22,746. The primary outcome was readmission for six studies (five all-cause and two CAP-specific), mortality for 15 (15 all-cause), and one study had a composite outcome of all-cause readmission and mortality.

Table 1.

Studies Examining the Impact of Social Factors on Risk of Readmission or Mortality in Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| Source | Study Type | Data Source (Study Period) | Study Location | No. of Hospitals/ No. of Patients | Study Outcome | Follow-up Period | Analytic Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson et al. 199256 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, American Hospital Association File, Other Government Admin., (1981–1982, 1985–1986) | US | 297/11,242 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days, 6 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Saitz et al. 199730 | Retrospective cohort | Massachusetts Health Data Consortium, (1992) | MA | Multiple, No. not presented /23,198 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Whittle et al. 199820 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative (1990) | PA | Multiple, No. not presented /22,294 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 30 days*†, 3 months* | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Torres et al. 199861 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record Review (1990–1994) | PA | Multiple, No. not presented /71 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Not presented |

| Kaplan et al. 200224 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Admin., Hospital Admin., Other Government Admin., (1997) | US | Multiple, No. not presented /623,718 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Herzog et al. 2003 19 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, Medical Record, (1998–1999) | US | 4,341/12,566 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | mean 6 months*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Bohannon et al. 200362 | Retrospective cohort | Hospital Administrative (1999–2000) | CT | 1/892 | All-cause Readmission | 1 year | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Mortensen et al. 200428 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, Medical Record, (1998–1999) | PA | 101/960 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Oliver et al. 200425 | Retrospective cohort | California Hospital Discharge Data, (1996–1999) | CA | Multiple, No. not presented /41,581 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Vrbova et al. 20058 | Retrospective cohort | Other Government Administrative, (1995–2001) | Canada | Multiple, No. not presented /60,457 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days, 1 year | Multivariate logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression |

| de Roux et al. 200631 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, (1996–2001) | Spain | 1/1,347 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| El-Solh et al. 200663 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, NY Department of Public Health, Social Security Adminstration Death Master File, (2003–2004) | NY | 1/301 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission Composite | 1 year*† | Multivariate logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression |

| McGregor et al. 200623 | Retrospective cohort | Other Insurance Co. Admin., Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion Program, Medical Record, Other Government Admin, (1990–2001) | Canada | 1/434 | All-cause Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Vaughan-Sarrazin et al. 200732 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, Other Government Admin, (1996–2002) | US | Multiple, No. not presented/861,610 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Tabak et al. 2007 26 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Cardinal Health Research Database, (2000–2003) | US | 266 /824,393 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Boot strapping, recursive partitioning |

| Jasti et al. 200822 | RCT Cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report/Survey, RCT Cohort, (1998–1999) | PA | 7/577 | CAP-specific Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Abrams et al. 200829 | Retrospective cohort | VA Patient Treatment File , Outpt. Care Files Decision Support System Laboratory File, (2003–2004) | US | 168/32,073 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Polsky et al. 200827 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, VA, Census Data, (1998–2004) | US | 3369 /8,958,337 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days, 2 years | Multivariate logistic regression, Other Multivariate time to event |

| Ross et al. 201016 | Cross- Sectional | VA Patient Treatment File , Other Government Admin, (2006–2009) | US | 124/31,126 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days | Multivariate Hierarchical Regression, boot strapping |

| Joynt et al. 201121 | Retrospective Cohort | Medicare Administrative, (2006–2008) | US | 4,588 /1,236,751 | All-cause & CAP-specific readmission | 30 days | Multivariate Logistic Regression |

*Mortality follow-up; †Readmission follow-up

Table 2.

Studies Examining the Impact of Social Factors on Risk of Readmission or Mortality in Heart Failure

| Source | Study Type | Data Source (Study Period) | Study Location | No. of Hospitals/ No. of Patients | Study Outcome | Follow-up Period | Analytic Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinson, et al. 199064 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record, Self-report, (1987) | Missouri | 1/140 | All-cause Readmission | 3 months | Univariate |

| Pearson et al. 199256 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, American Hospital Association File, Other Government Admin., (1981–1982, 1985–1986) | USA | 297/11,242 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days, 6 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Krumholz et al. 199742 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative (1990–1994) | Connecticut | Multiple, No. not Presented /17,448 | All-cause Readmission; All-cause Readmission and Mortality Composite | 6 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Philbin et al. 19989 | Retrospective Cohort | Medical Record, SPARCS, Other Government Admin., (1995) | New York | 236/45,894 | HF-specific readmission & All-cause mortality | In hospital*, 1 year† | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Philbin et al. 199811 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, SPARCS, Other Government Admin., (1995) | New York | 43,157/43,157 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 6 months*† | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Ni et al. 199857 | Retrospective Cohort | Oregon Association of Hospital and Health Systems, (1995) | Oregon | Multiple, No. not Presented /5,821 | HF-specific readmission & All-cause Mortality | In hospital*, 3 months† | Multivariate Logistic regression |

| Afzal et al. 199965 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, (1999) | Michigan | 1/163 | type of readmission not discussed | 6 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Philbin et al. 199910 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, SPARCS, Other Government Admin., (1995) | New York | 236/42,731 | HF-specific Readmission | 6 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Kossovsky et al. 200034 | Case–control | Hospital Administrative, Medical Record, (1993–1998) | Switzerland | 1/442 | All-cause & HF-specific Readmission | 1 month | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Krumholz et al. 200066 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, Hospital Administrative, Medical Record, (1994–1995) | Connecticut | 18/2,176 | All-cause & HF-specific Readmission | 6 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Struthers et al. 200048 | Retrospective cohort | Hospital Administrative, Medical Record, (1989– 1994) | UK | Multiple, No. not presented/478 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission; Cardiac Readmission | 2 years*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Philbin et al. 200144 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, SPARCS, Other Government Admin., (1995) | New York | 236/41,776 | HF-specific Readmission | one year | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Jiang et al. 200133 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record (1997–1998) | North Carolina | 1/374 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 3 months*†, 1 year*† | Multivariate logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Tsuchihashi et al. 200146 | Prospective cohort | Hospital Administrative, Medical Record, Self-Report, (1997– 1999) | Japan | 5/230 | All-cause & cardiac mortality, HF-specific Readmission | mean 2.4 years*† | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Rathore et al. 200337 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Survey, Medicare Administrative, (1998–1999) | USA | Multiple, No. not presented /29,732 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 30 days*, 1 year*† | Multivariate logistic regression, Multivariate hierarchical regression |

| Feinglass et al. 200351 | Retrospective cohort | Hospital Admin, Other Government Admin., (1989–2001) | Illinois | 1/2,323 | All-cause Mortality | 1 month; 1, 3, & 5 years | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Luthi et al. 200341 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Medicare Administrative, (1995–1996) | Connecticut, Georgia, Oklahoma, Colorado, Virginia | 50/611 | All-cause Readmission | 21 months | MV logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression, MV Hierarchical regression |

| Chen et al. 200367 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record (1986–1999) | Taiwan | 1/234 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Schwarz et al. 200313 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, (not listed) | Ohio | 2/156 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 3 Months*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Opasich et al. 200335 | Prospective Cohort | Hospital Medical Record, Self-Report, Survey, (2000) | Italy | 417/2,127 | All-cause Mortality | In hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Zuccala et al. 200355 | Retrospective cohort | RCT cohort, (1988, 1991, 1993, 1995, 1997) | Italy | 81/1,113 | All-cause Mortality | In hospital, 1 year | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Lee et al. 200353 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Other Government Admin., (1997–2001) | Canada | 48/4,031 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days, one year | MV logistic regression, Boot strap |

| Formiga et al. 200668 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record (2001–2002) | Spain | 1/88 | HF-specific Readmission, All cardiac mortality | 30 days*† 1 year*† | Univariate |

| Goldberg et al. 200554 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record (2000) | Massachusetts | 11/2,604 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Luttik et al. 200669 | Retrospective cohort | Hospital Administrative, Medical Record, Self-Report, RCT, (1994– 1997) | Netherlands | 1/179 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission Composite | 9 months*† | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Rathore et al. 200645 | Retrospective | Medicare Administrative, (1998–1999) | USA | Multiple, No. not | All-cause Mortality & | 30 day*, | MV hierarchical |

| Garty et al. 200752 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record, Other Government Admin, Self-Report, (2003–2004) | Israel | 25/4,102 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital, 1 & 3 months, 1 year | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Tabak et al. 200726 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Cardinal Health Research Database, (2000–2003) | USA | 266/824,393 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | boot strapping, recursive partitioning |

| Vaughan-, Sarrazin et al. 200732 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, Other Government Admin, (1996–2002) | USA | Multiple, No. not presented /861,610 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Howie-Esquivel et al. 200770 | Prospective Cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, (2004–2005) | California | 1/84 | HF-specific and cardiac readmission | 3 months | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Najafi et al. 200771 | Retrospective cohort | Other Government Admin, (1996–1999,2003–2004) | Australia | Multiple, No. not presented /1,161,526 | All-cause Mortality | In hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Roe-Prior et al. 200736 | Retrospective cohort | Self-Report, RCT cohort, (1994–2004) | Pennsylvania | 4/103 | All-cause & HF-specific Readmission | 3 months | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Abrams et al. 200829 | Retrospective cohort | VA Patient Treatment File , Outpt Care Files Decision Support System Laboratory File, (2003–2004) | USA | 168/32,073 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Howie-Esquivel et al. 200843 | Prospective cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, (2004–2005) | California | 1/54 | HF-specific and cardiac readmission | 3 months | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Fonarrow et al. 200858 | Prospective cohort | OPTIMIZE-HF Registry (2003–2004) | USA | 259/48,612 | All-cause Mortality & All-cause Mortality and Readmission composite | In Hospital*, 2,3 months*† | Multivariate logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Mullens et al. 200872 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Other Government Admin, (2000–2006) | Ohio | 1/278 | All-cause Mortality & HF-Specific Readmission | median 54 months*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Polsky et al. 200827 | Retrospective cohort | Medicare Administrative, VA, Census Data, (1998–2004) | USA | 3,369 /8,958,337 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days, 2 years | Multivariate logistic regression, Other Multivariate time to event |

| Albert et al. 200947 | Retrospective Cohort | OPTIMIZE-HF Registry (2003– 2004) | USA | 259/48,612 | All-cause Mortality; Mortality & Readmission Composite | In Hospital*, 2,3 Months*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Ambardekar et al. 200959 | Retrospective Cohort | GWTG-HR Registry (2005–2007) | USA | 236/54,322 | All-cause Mortality | In hospital | Multivariable logistic regression |

| Aranda et al. 200940 | Retrospective Cohort | Medicare Administrative (2002–2004) | USA | Multiple, No. not presented /28,919 | All-cause Readmission | 6 & 9 months | Multivariable logistic regression |

| Lofvenmark et al. 200973 | Prospective Cohort | Medical Record, Self-Report, (2006–2007) | Stockholm | 1/149 | All-cause Readmission | 1 year | Multivariable logistic regression |

| Moser et al. 200974 | Retrospective cohort | Self-Report, RCT cohort, (not discussed) | USA & Canada | 26/425 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission Composite | 6 months*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Saczynski et al. 200950 | Retrospective cohort | Medical Record, Other Government Admin., (1995–2000) | Massachusetts | 11/4,534 | All-cause Mortality | In Hospital, 30 days, one year | Multivariate logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Ross et al. 201016 | Cross- Sectional | VA Patient Treatment File, Other Government Admin, (2006–2009) | USA | 124/26,379 | All-cause Mortality | 30 days | Multivariable Hierarchical Regression, boot strapping |

| Amarasing- ham et al. 201012 | Retrospective Cohort | Medical Record, Other Government Admin., (2007–2008) | Texas | 1/1,372 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression, bootstrapping |

| Kociol et al. 201038 | Retrospective Cohort | Medicare Administrative, OPTIMIZE-HF Registry, (2003–2005) | USA | 259/20,063 | All-cause Mortality & Readmission | 1 year*† | Cox proportional hazards regression |

| Muus et al. 201075 | Retrospective Cohort | VA Patient Treatment File , Other Government Admin, (2005–2007) | USA | Multiple, No. not presented /36,566 | HF-specific Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Chioncel et al. 201149 | Prospective Cohort | Hospital Medical Record (2008–2009) | Romania | 13/3,224 | All-cause Mortality | In hospital | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Joynt et al. 201121 | Retrospective Cohort | Medicare Administrative, (2006–2008) | USA | 4,560 /1,346,768 | All-cause & HF specific Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Rodriguez et al. 201139 | Retrospective Cohort | Medicare Administrative, American Hospital Assoc., Hospital Quality Alliance, (2006–2008) | USA | 4,550 /1,734,101 | All-cause Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Watson et al. 201114 | Retrospective Cohort | Hospital Medical Record, (2007–2008) | Massachusetts | 1/729 | All-cause Readmission | 30 days | Multivariate logistic regression |

| Zuluaga et al. 201160 | Prospective Cohort | Self-Report, Hospital Medical Record, Other Government Admin, (2000–2005) | Spain | 4/433 | All-cause Mortality | 5 years | Cox proportional hazards regression |

*Mortality follow-up; †Readmission follow-up

For HF, there were 36 retrospective and 14 prospective cohort studies, one case control and one cross-sectional. Similar to CAP, most HF studies (17) were based on administrative data sets. Twenty-two used a combination of administrative database and medical record or interview, and 13 used only medical record or interview. Fourteen were single-site studies. The sample size for HF studies ranged from 54 to 8,958,337 with a median of 3,628. The primary outcome was readmission for 35 studies (18 all-cause, 14 HF-specific, 3 cardiac-specific, and one not discussed), mortality for 32 (32 all-cause and 2 cardiac-cause), and five had a composite outcome of readmission and mortality.

Social Factors Associated with Readmission in Pneumonia

Social factors that were examined in CAP readmission studies are listed in Table 3. The presence and magnitude of associations for multivariate analysis are included in the table. Most studies examined Level 1 demographic factors and found that the elderly19,20 and non-whites19–21 had higher readmission rates, but the impact of gender was mixed. Only five studies did multivariate analyses of higher level social factors; of these, three Level 2 variables were associated with worse outcomes. Jasti et al.22 reported increased risk of readmission for patients with lower education and who were unemployed. McGregor et al.23 found an increased risk of readmission for lower income patients. Of the two studies that assessed Level 3 factors, no association was seen for nursing home residence19 or rurality.20

Table 3.

Association between Social Factors and Readmission in Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| Social Factor | Variable Examined | Significant UV association/ UV analysis done | Significant MV association/ MV analysis done | MV Magnitude of Association‡ Ratio (95 % CI), p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Factors | ||||

| Age19,20,22,23,62,63 | 6 | 1/4 | 1/4 | age per year HR = 0.94 (0.91–0.97), <0.000219 |

| 80–84 OR = 1.14 (0.98–1.32), (NS)20 | ||||

| ≥65 OR = 2.7 (0.3–21.6), (NS)22 | ||||

| not specified (no ratio, NS)63 | ||||

| Gender19,20,23,62,63 | 5 | 2/3 | 4/4 | Male OR = 0.675 (0.52–0.88), 0.00462 |

| Male OR = 1.21 (1.11–1.32)20 | ||||

| Male OR = 2.05 (1.01–4.18)23 | ||||

| Male HR = 0.59 (0.56–0.63), <0.000119 | ||||

| Race19–21,62 | 4 | 1/2 | 2/3 | Black OR = 1.15 (1.12–1.17), <0.00121 |

| Black OR = 1.25 (1.05–1.49)20 | ||||

| Non-white HR = 1.05 (0.96–1.14), 0.23, (NS)19 | ||||

| Level 2 Factors | ||||

| Education22 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | <high school OR = 2 (1.1–3.4), <0.0522 |

| Employment22 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | unemployed OR = 3.7 (1.1–12.3), <0.0522 |

| Income23 | 1 | 0/0 | 1/1 | On income assistance OR = 2.65 (1.38–5.09), <0.0123 |

| Level 3 Factors | ||||

| Social Environment | ||||

| Living Status23 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| NH resident19 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/1 | NH HR = 1.0 (0.92–1.08), 0.96, (NS)19 |

| Behavioral | ||||

| Smoking23,63 | 2 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Substance Abuse23 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Neighborhood | ||||

| Urban vs. Rural20 | 1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | Urban OR = 1.02 (0.91–1.15) , (NS)20 |

UV univariate analysis, MV multivariate analysis, NH nursing home, N/A not applicable, NS not significant; ‡data reported varies based on information available in primary study, not all studies reported CI or p values

Social Factors Associated with Mortality in Pneumonia

The associations between social factors and mortality for CAP are shown in Table 4. Level 1 demographics were most commonly evaluated, and of the studies that did multivariate analyses, increased mortality was observed for older8,16,20,24–26 and male8,20,24 patients. The pattern for race was mixed with one study showing decreased mortality27 for blacks and two showing no statistical difference.27,28 Hispanics25 and Asians25 had lower mortality. Level 2 and 3 social factors were examined less frequently. However, those that did found that the presence of psychiatric comorbidity paradoxically decreased mortality29 but there was no impact of income.8 Only one Level 3 social factor, being a nursing home resident, significantly increased the odds of mortality (OR = 1.5).24 The use of alcohol,30,31 distance to hospital32 and urban neighborhood20 were examined but not significantly associated with increased mortality.

Table 4.

Association between Social Factors and Mortality* in Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| Social Factor | Variable Examined | Significant UV association/ UV analysis done | Significant MV association/ MV analysis done | MV Magnitude of Association‡ Ratio (95 % CI), p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Factors | ||||

| Age8,16,20,24–26,28,29,31,32,61 | 11 | 4/5 | 7/7 | >65 OR = 1.05 (1.04–1.05)16 |

| ≥81 OR = 0.95 (0.92–0.97), <0.00132 | ||||

| ≥85 OR = 2.66 (2.33–3.04)20 | ||||

| ≥85 OR = 3.02 (2.83–3.21), <0.00018 | ||||

| ≥90 OR = 1.75 (1.69–1.81)24 | ||||

| ≥100 OR = 10.56 (6.22–17.9)25 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.035 (1.02–1.04), <0.000126 | ||||

| Gender8,16,20,24–26,28,29,31,32,56 | 11 | 3/4 | 3/6 | Male OR = 1.15 (1.13–1.17)24 |

| Male OR = 1.23 (1.15–1.33)20 | ||||

| Male OR = 1.28 (1.22–1.34), <0.00018 | ||||

| Male OR = 1.02 (0.96–1.08), (NS)25 | ||||

| Male OR = 1.31 (0.99–1.73), (NS)16 | ||||

| Male mean rate difference +0.2 (−2.2- + 2.7)56 | ||||

| Race20,25,27–29,32 | 6 | 1/3 | 2/4 | Black mean rate difference −1.7, p value <0.0527 |

| Black OR = 0.40 (0.16–1.0), (NS)28 | ||||

| Black OR = 1.06 (0.91–1.24), (NS)20 | ||||

| Asian OR = 0.83 (0.75–0.91)25 | ||||

| Hispanic ethnicity25 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Hispanic OR = 0.9 (0.82–0.98)25 |

| Level 2 Factors | ||||

| Insurance32 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Mental Health29 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Psychiatric comorbidity OR = 0.63 (0.52–0.77), <0.00129 |

| Income8,32 | 2 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Low Income OR = 1.04 (0.97–1.12), 0.23, (NS)8 |

| Level 3 Factors | ||||

| Social Environment | ||||

| NH resident24 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | NH = OR 1.5 (1.44–1.55)24 |

| Behavioral | ||||

| Smoking31 | 1 | 0/1 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Alcohol30,31 | 2 | 1/2 | 0/2 | alcohol use OR = 1.0 (0.7–1.4), (NS)30 |

| not specified (no ratio, NS)31 | ||||

| Neighborhood | ||||

| Urban v. Rural20 | 1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | Urban OR = 1.08 (0.98–1.2), (NS)20 |

| Distance to hospital32 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/1 | ≤25 miles OR = 1.0 (0.99–1.01), 0.77, (NS)32 |

*Results shown are only for short-term mortality (≤30 days post-discharge or in hospital); UV univariate analysis, MV multivariate analysis, NH nursing home, N/A not applicable, NS not significant; ‡data reported varies based on information available in primary study, not all studies reported CI or p values

Social Factors Associated with Readmission in Heart Failure

Table 5 shows the social factors that were examined in relation to readmissions in HF. There were many more HF studies that looked for sociodemographic effects. Increased readmissions were consistently seen among the elderly33–36 and blacks,9,10,21,37,38 Hispanics39 also did worse. The results for gender were very mixed; five studies found no effect,13,14,38,40,41 two studies found that men did worse,12,42 and one that men did better.43

Table 5.

Association Between Social Factors and Readmission in Heart Failure

| Social Factor | Variable Examined | Significant UV association/ UV analysis done | Significant MV association/ MV analysis done | MV Magnitude of Association‡ Ratio (95 % CI), p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Factors | ||||

| Age9–14,33–38,40–46,48,57,58,64–66,68–70,72–76 | 33 | 6/14 | 4/10 | 65–74 OR = 0.83 (0.75–0.91)40 |

| ≥80 OR = 4.1 (1.6–11), 0.00434 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.03 (1.012–1.05), 0.00233 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.05 (1.03–1.08)35 | ||||

| Age per year OR 1.17, 0.02136 | ||||

| >65yo OR = 1.45 (0.83–2.55), 0.2, (NS)14 | ||||

| 75–84 OR = 1.08 (1–1.16), (NS)42 | ||||

| ≥80 HR = 1.05 (0.99–1.12), 0.13, (NS)38 | ||||

| Age per year HR = 0.97 (0.92–1.02), (NS)13 | ||||

| Age per year HR = 1.03 (0.99–1.06), 0.117, (NS)74 | ||||

| Gender9–14,34–38,40–46,48,57,58,64–66,68–70,72,73,75 | 30 | 3/15 | 4/8 | Male OR = 1.12 (1.05–1.2)42 |

| Male OR = 1.37 (1.02–1.84), 0.0312 | ||||

| Male HR = 0.40 (0.16–0.96), 0.0443 | ||||

| Male OR = 1.00 (0.94–1.06), (NS)40 | ||||

| Male OR = 1.07 (0.66–1.74), 0.78, (NS)14 | ||||

| Male HR = 0.98 (0.94–1.02), 0.37, (NS)38 | ||||

| Male HR = 1.23 (0.64–2.36), (NS)13 | ||||

| Male rate ratio 1.2 (0.96–1.49), (NS)41 | ||||

| Race12,21,38,40,65,75,9–11,36,37,41–45,58,64,66,70,72 | 21 | 7/10 | 6/8 | Black OR = 1.04 (1.03–1.06), <0.00121 |

| Black OR = 1.28 (1.16–1.41)10 | ||||

| Black OR = 1.30 (1.22–1.39), 0.00019 | ||||

| Black HR = 1.24 (1.17–1.33), <0.00138 | ||||

| Black RR = 1.09 (1.06–1.13)37 | ||||

| Black OR = 1.05 (0.97–1.14), (NS)40 | ||||

| Non-white OR = 0.88 (0.78–1.01), (NS)42 | ||||

| not specified (no ratio, NS)65 | ||||

| Ethnicity39,70 | 2 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Hispanic OR = 1.11 (1.07–1.14), <0.00139 |

| Level 2 Factors | ||||

| Insurance9–12,14,57,65 | 7 | 3/4 | 3/4 | Medicaid OR = 1.74 (1.4–2.16), <0.0111 |

| Medicaid OR = 1.92 (1.57–2.36)10 | ||||

| Medicare OR = 1.59 (1.17–2.17), 0.00412 | ||||

| Medicare OR = 1.66 (1.38–2)10 | ||||

| Public insurance OR = 0.61 (0.34–1.07), 0.08, (NS)14 | ||||

| Marital Status12,14,36,43,46,69,73,75 | 8 | 1/4 | 2/3 | Not married OR = 1.28, 0.02136 |

| Single OR = 1.47 (1.08–2.01), 0.0212 | ||||

| Not married OR = 0.72 (0.45–1.15), 0.17, (NS)14 | ||||

| Mental Health12,14,33,77 | 5 | 2/4 | 2/5 | Depression OR = 1.44 (1–2.07), 0.05, (NS)12 |

| Depression OR = 1.21 (0.99–1.47), 0.06, (NS)47 | ||||

| Depression OR = 1.83 (0.93–3.57), 0.08, (NS)33 | ||||

| Depression OR = 1.14 (0.68–1.91), 0.62, (NS)14 | ||||

| Depression HR = 1.03 (0.98–1.09), 0.25, (NS)38 | ||||

| Anxiety OR = 0.97 (0.58–1.62), 0.87, (NS)14 | ||||

| Education13,36,65,73 | 4 | 0/0 | 0/2 | Lower Education OR 1.2, 0.11, (NS)36 |

| High School Graduate HR = 0.51 (0.25–1.02), (NS)13 | ||||

| Income36,44,46,75 | 4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | Lower Income OR = 1.18 (1.1–1.26), <0.000144 |

| Lower Income OR = 1.18, 0.06, (NS)36 | ||||

| Socioeconomic Status12,45,69 | 3 | 2/2 | 1/2 | Lower SES RR = 1.08 (1.03–1.12), <0.00145 |

| Lower SES OR = 1.3 (0.98–1.74), 0.08, (NS)12 | ||||

| Employment36,46,65 | 3 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Unemployed OR = 2.59 (1.22–5.48), 0.01346 |

| Level 3 Factors | ||||

| Social Environment | ||||

| Social Support13,48,64 | 3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | Higher Social Support HR = 0.93 (0.89–0.98), <0.00113 |

| Social Deprivation RR = 1.013 (0.94–1.1), 0.74, (NS)48 | ||||

| Living Status34,46,68 | 3 | 0/2 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Nursing home resident44 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Loneliness73 | 1 | 1/1 | 0/0 | N/A |

| No. of home address changes in prior year12 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | More changes OR = 1.13 (1.07–1.19), <0.00112 |

| Behavioral | ||||

| Left Against Medical Advice10–12 | 3 | 1/1 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Smoking38,41,43,58,64,65,72 | 7 | 0/1 | 1/1 | Smoker HR = 1.07 (1.01–1.13), 0.0338 |

| Substance Abuse10,12 | 2 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Cocaine use OR = 1.78 (1.17–2.72), 0.0112 |

| Alcohol10 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Adherence w/follow-up visit12,14,65 | 3 | 2/2 | 1/2 | Missed appt. OR = 1.73 (1.06–2.8), 0.0314 |

| Missed appt. OR = 1.35 (0.99–1.83), 0.06, (NS)12 | ||||

| Medical adherence14 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Non-adherence OR = 1.72 (1.07–2.76), 0.0314 |

| Decline medical service14 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Decline OR = 1.75 (1.07–2.87), 0.0314 |

| Adherence to diet58,64 | 2 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Non-adherence OR = 0.94 (0.73–1.21), 0.62, (NS)58 |

| Medication adherence58,64 | 2 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Non-adherence OR = 1.03 (0.82–1.29), 0.8, (NS)58 |

| Sociocognitive | ||||

| English proficiency14 | 1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | Spanish OR = 0.97 (0.27–3.56), (NS)14 |

| Italian OR = 1.64 (0.31–8.6), (NS)14 | ||||

| Neighborhood | ||||

| Urban vs. Rural10,11,44,75 | 4 | 0/2 | 1/1 | Rural OR = 0.87 (0.78–0.98)10 |

UV univariate analysis, MV multivariate analysis, NH nursing home, N/A not applicable, NS not significant; ‡data reported varies based on information available in primary study, not all studies reported CI or p values

Many Level 2 factors increased the risk of readmission in HF. Patients with Medicare10,12 or Medicaid10,11 had 59 % to 92 % greater odds of readmission (See Table 5 for details). Being unmarried36 or single12 increased readmissions. Several related measures of low socioeconomic44–46 status were found to significantly increase readmission, or showed similar borderline trends.12,36 Comorbid depression was borderline in three,12,33,47 and not associated14,38 with readmission in two others. The mental health comorbidity examined the most was depression; the odds ratio for these studies ranged from 1.21 to 1.83.

Compared to CAP, more HF studies evaluated Level 3 domains. In the social environment domain, Schwarz et al.13 showed that social support decreased readmission, but Struthers et al.48 showed no effect of social deprivation. As a measure of home stability, Amarasingham et al.12 showed that patients with more home address changes in the prior year were at increased risk of readmission. Behavioral factors significantly related to outcomes included smoking38 and cocaine12 use. Several measures of patient non-adherence were also associated with readmission, such as: a missed post-discharge follow-up appointment,14 non-adherence to the medical plan,14 and declining medical service as inpatient.14 In the socio-cognitive domain, there were no demonstrated language proficiency effects.14 Patients living in a rural setting had fewer readmissions.10

Social Factors Associated with Mortality in Heart Failure

The associations between social factors and short-term mortality in HF are shown in Table 6. Level 1 factors showed increased mortality in older16,26,49–53 patients, while the results for gender were mixed, with three studies showing no difference,16,54,55 three showing increased mortality,9,51,56 and one decreased52 mortality. Black HF patients had decreased mortality.9,27,37,51

Table 6.

Association Between Social Factors and Mortality* in Heart Failure

| Social Factor | Variable Examined | Significant UV association/ UV analysis done | Significant MV association/ MV analysis done | MV Magnitude of Association‡ Ratio (95 % CI), p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 Factors | ||||

| Age9,16,26,29,32,37,45,49–55,57–59,67,68,71 | 19 | 2/4 | 9/11 | >65 OR = 1.05 (1.04–1.05)16 |

| ≥80 RR = 1.5 (1.3–1.6), <0.000151 | ||||

| ≥81 OR = 0.92 (0.89–0.95), <0.00132 | ||||

| ≥85 OR = 2.99 (1.97–4.52)50 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.034 (1.02–1.04), <0.000126 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.063 (1.03–1.1), <0.00149 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.39 (1.19–1.63)52 | ||||

| Age per year OR = 1.7 (1.45–1.99), <0.00153 | ||||

| Age per year, <0.0558 | ||||

| ≥85 OR = 2.38 (0.69–8.2) , (NS)54 | ||||

| Age per year RR = 1.01 (0.98–1.04), (NS)55 | ||||

| Gender9,16,26,29,32,37,45,50–59,67,68,71 | 20 | 1/4 | 3/7 | Male OR = 0.50 (0.36–0.70)52 |

| Male OR = 1.12 (1.05–1.23), 0.00089 | ||||

| Male RR = 1.3 (1.2–1.4), <0.000151 | ||||

| Male, <0.00171 | ||||

| Male mean rate difference +1.4 (−1.2- + 4.0)56 | ||||

| Male OR = 0.94 (0.63–1.4), (NS)54 | ||||

| Male OR = 1.0 (0.73–1.37), (NS)16 | ||||

| Male RR = 0.79 (0.51–1.25), (NS)55 | ||||

| Race9,27,29,32,37,45,50,51,58,59 | 10 | 3/3 | 4/4 | Black = OR 0.83 (0.73–0.94), 0.0039 |

| Black = RR 0.69 (0.59–0.8), <0.000151 | ||||

| Black = RR 0.78 (0.68–0.91)37 | ||||

| Black mean rate difference −1.7, p value <0.0527 | ||||

| Level 2 Factors | ||||

| Insurance9,32,57,59 | 4 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Medicaid = OR 0.66 (0.3–1.4), 0.68, (NS)57 |

| Mental Health29,47 | 2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | Psychiatric comorbidity OR = 0.7 (0.57–0.86), <0.00129 |

| Depression OR = 1.1 (0.9–1.34), 0.35, (NS)47 | ||||

| Education55 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Education RR = 1.05 (0.98–1.12), (NS)55 |

| Income32 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Socioeconomic Status45 | 1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | Lower SES RR = 1.13 (0.92–1.38), 0.26, (NS)45 |

| Level 3 Factors | ||||

| Social Environment | ||||

| Living Status60,68 | 2 | 1/2 | 1/1 | No elevator HR = 1.39 (1.07–1.8), <0.0560 |

| Frequently feels cold HR 1.39 (1.01–1.92), <0.0560 | ||||

| No indoor bathroom HR = 0.7 (0.24–2), (NS)60 | ||||

| No bathtub/shower HR = 1.0 (0.41–2.32), (NS)60 | ||||

| No washing machine HR = 1.09 (0.52–2.27), (NS)60 | ||||

| No hot water HR = 1.11 (0.55–2.24), (NS)60 | ||||

| No phone HR 1.37 (0.71–2.64), (NS)60 | ||||

| No individual bedroom HR = 1.6 (1.0–2.6), (NS)60 | ||||

| Behavioral | ||||

| Smoking50,58,67 | 3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Alcohol67 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | N/A |

| Adherence to diet58 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Non-adherence OR = 0.69 (0.48–1), 0.05, (NS)58 |

| Medication adherence58 | 1 | 0/0 | 0/1 | Non-adherence OR = 0.88 (0.67–1.17), 0.39, (NS)58 |

| Medical adherence59 | 1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | Non-adherence OR = 0.66 (0.51–0.86), 0.001759 |

| Neighborhood | ||||

| Distance to hospital32 | 1 | 0/0 | 1/1 | ≤25 miles OR = 0.95 (0.92–0.98), 0.00232 |

*Results shown are only for short-term mortality (≤30 days post-discharge or in hospital); UV univariate analysis, MV multivariate analysis, N/A not applicable, NS not significant; ‡ data reported varies based on information available in primary study, not all studies reported CI or p values

Level 2 factors that were examined but were not significant included insurance,57 education,55 and socioeconomic status.45 Abrams et al.29 showed that patients with a psychiatric comorbidity had decreased odds of mortality. Level 3 factors examined included non-adherence behavior; diet non-adherence58 and medical plan non-adherence59 were associated with decreased short-term mortality, while medication non-adherence58 showed no difference. Living closer to a hospital32 decreased mortality. In the social environment domain, Zuluaga et al.60 examined the impact of housing resources on mortality, and found that not having an elevator and frequently feeling cold at home were associated with increased mortality.

COMMENTS

Our systematic review identified 72 studies that had some information on the impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in patients with CAP and HF, but these varied widely in purpose, design, data sources, outcomes, how social factors were defined and ascertained, and degree of analytic sophistication. The heterogeneity of the studies and mixed findings made it difficult to synthesize the results and definitively assess the impact of a given social factor on outcomes. Despite these variations and uncertainties, a broad spectrum of social factors were associated with worse outcomes in two common but different conditions: CAP, an acute infectious illness, and HF, a chronic disease with acute exacerbations.

There were some themes across conditions and outcomes. Among Level 1 sociodemographic characteristics, older age was clearly the most consistent risk factor. Findings of disparities by race/ethnicity or gender were very mixed. Among Level 2 factors, various measures of low socioeconomic status (low income, education, Medicaid insurance) clearly increased risk. While few studies examined the same Level 3 variables, there was proof of concept evidence that social environment (housing stability, social support), behavioral (adherence, smoking, substance abuse), socio-cognitive (language proficiency), and neighborhood (rurality, distance to hospital) factors were independent predictors of poor post-hospital outcomes.

Our review confirms and extends the findings of a systematic review by Ross et al.,17 which also found that several Level 1 and a few Level 2 social factors were associated with readmissions among patients with HF, though the magnitude of association was not listed. Our review extends this finding to mortality in HF patients, to patients with CAP, and has uncovered important prognostic relationships with a broader range of social disadvantage constructs. These findings also provide empirical evidence for our proposed conceptual model and the commonly held belief that a spectrum of different level social factors influence post-discharge readmissions and mortality.

CMS publically reports on and compares hospitals according to 30-day readmission and mortality rates for CAP and HF, among other conditions.3–6 At present, the current CMS readmission and mortality models for CAP and HF do not adjust for any Level 2 and 3 social factors identified in this review. Future research should attempt to take into account more of these other social factors that may affect adverse outcomes, but are not within the providers control and are independent of the quality of inpatient care and discharge coordination.

Several limitations of this review are worth noting. Because we considered social factors very broadly and definitions of these constructs vary, our search strategy may have missed some articles because there is not one global MeSH term on this topic. To minimize this risk, we searched for a large number of MeSH terms and keywords based on input of the literature, clinical experts and an expert medical librarian. The impact of social factors was often not the primary focus of the included studies, explaining why many did not assess this in depth or with sophisticated multivariate techniques. Finally, since many studies collected information on social factors but did not statistically analyze them or only performed univariate analysis, it is also possible that negative results were not reported because they were not statistically significant.

Future research should focus on the impact of Level 2 and 3 social factors on readmission and mortality, and seek to identify the independent contribution of different sociodemographic, socioeconomic, social environment, behavioral, socio-cognitive, and neighborhood attributes on risk of readmission and mortality. Given the dramatic growth in hospital adoption of electronic medical records (EMR), which often contain richer data on these different social domains, there should now be more opportunities than ever to examine these issues in greater depth with large patient populations, and in a way not possible with administrative billing databases. For example, a recent study by Amarasingham et al.12 developed a readmission and mortality prediction model leveraging a wide range of social disadvantage factors extractable from the EMR and census track data. This study showed that the addition of several Level 2 and 3 social disadvantage variables to a clinical severity model significantly improved model performance and surpassed the CMS HF readmission model. There are also initiatives underway for hospitals to screen for and document in the EMR key prognostic attributes, such as language proficiency, health literacy, and social support, during the nursing intake or discharge planning process. Thus, additional measures of social disadvantage are likely to become more readily ascertainable through electronic means.

Finally, from a clinical and quality improvement perspective, the different social disadvantage prognostic factors outlined in this review could be used by physicians, case managers and discharge planners to identify patients who may be at particularly high risk of readmission and mortality because of non-clinical, vulnerability factors. Different and more intensive follow-up strategies will likely be necessary in these high social risk patients to substantially reduce their chance of poor post-discharge outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Funding/Support

Dr. Calvillo–King was supported by a Diversity Supplement from the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, and NIH CTSA (5UL1 RR024982-05). Dr. Halm was supported in part by NIH (5TL1 RR0249884-05), and NIH CTSA (5UL1 RR024982-05).

Prior Presentations

This study was presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine 34th Annual Meeting, May 6, 2011, Phoenix, Arizona and at the Academy Health Annual Research Meeting, June 13, 2011, Seattle, Washington.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Medicaid CfMa. Publicly reporting risk-standardized, 30-day readmission measures for AMI, HF and PN. http://qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier3&cid=1219069855273. September 7, 2012.

- 2.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2006;113(13):1693–1701. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratzler DW, Normand S-LT, Wang Y, et al. An administrative claims model for profiling hospital 30-day mortality rates for pneumonia patients. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e17401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keenan PS, Normand S-LT, Lin Z, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(1):29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindenauer PK, Normand S-LT, Drye EE, et al. Development, validation, and results of a measure of 30-day readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia. J Hosp Med (Online) 2011;6(3):142–150. doi: 10.1002/jhm.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Heal Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vrbova L, Mamdani M, Moineddin R, Jaakimainen L, Upshur R. Does socioeconomic status affect mortality subsequent to hospital admission for community acquired pneumonia among older persons? J Negat Results Biomed. 2005;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philbin E, DiSalvo T. Influence of race and gender on care process, resource use, and hospital-based outcomes in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(1):76–81. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philbin E, DiSalvo T. Prediction of hospital readmission for heart failure: development of a simple risk score based on administrative data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philbin E, DiSalvo T. Managed care for congestive heart failure: influence of payer status on process of care, resource utilization, and short-term outcomes. Am Heart J. 1998;136(3):553–561. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amarasingham R, Moore BJ, Tabak YP, et al. An automated model to identify heart failure patients at risk for 30-day readmission or death using electronic medical record data. Med Care. 2010;48(11):981–988. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef60d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz K, Elman C. Identification of factors predictive of hospital readmissions for patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32(2):88–99. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2003.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson AJ, O’Rourke J, Jethwani K, et al. Linking electronic health record-extracted psychosocial data in real-time to risk of readmission for heart failure. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(4):319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson MA, Levsen J, Dusio ME, et al. Evidenced-based factors in readmission of patients with heart failure. J Nurs Care Qual. 2006;21(2):160–167. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200604000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross JS, Maynard C, Krumholz HM, et al. Use of administrative claims models to assess 30-day mortality among Veterans Health Administration hospitals. Med Care. 2010;48(7):652–658. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbe35d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371–1386. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the New Millennium. Heal Aff. 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzog N, Bratzler D, Houck P, et al. Effects of previous influenza vaccination on subsequent readmission and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Am J Med. 2003;115(6):454–461. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittle J, Lin C, Lave J, et al. Relationship of provider characteristics to outcomes, process, and costs of care for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Care. 1998;36(7):977–987. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675–681. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jasti H, Mortensen E, Obrosky D, Kapoor W, Fine M. Causes and risk factors for rehospitalization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):550–556. doi: 10.1086/526526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGregor M, Reid R, Schulzer M, Fitzgerald J, Levy A, Cox M. Socioeconomic status and hospital utilization among younger adult pneumonia admissions at a Canadian hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:152. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan V, Angus D, Griffin M, Clermont G, Scott Watson R, Linde-Zwirble W. Hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: age- and sex-related patterns of care and outcome in the United States.[see comment] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(6):766–772. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2103038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver M, Stukenborg G, Wagner D, et al. Comorbid disease and the effect of race and ethnicity on in-hospital mortality from aspiration pneumonia. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96(11):1462–1469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabak Y, Johannes R, Silber J. Using automated clinical data for risk adjustment: development and validation of six disease-specific mortality predictive models for pay-for-performance. Med Care. 2007;45(8):789–805. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803d3b41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polsky D, Jha A, Lave J, et al. Short- and long-term mortality after an acute illness for elderly whites and blacks. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(4):1388–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortensen E, Cornell J, Whittle J. Racial variations in processes of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abrams T, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal G. Variations in the associations between psychiatric comorbidity and hospital mortality according to the method of identifying psychiatric diagnoses. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):317–322. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saitz R, Ghali W, Moskowitz M. The impact of alcohol-related diagnoses on pneumonia outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(13):1446–1452. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440340078008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Roux A, Cavalcanti M, Marcos M, et al. Impact of alcohol abuse in the etiology and severity of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2006;129(5):1219–1225. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Wakefield B, Rosenthal G. Mortality of Department of Veterans Affairs patients admitted to private sector hospitals for 5 common medical conditions. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(3):186–197. doi: 10.1177/1062860607300656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure.[see comment] Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kossovsky M, Sarasin F, Perneger T, Chopard P, Sigaud P, Gaspoz J. Unplanned readmissions of patients with congestive heart failure: do they reflect in-hospital quality of care or patient characteristics? Am J Med. 2000;109(5):386–390. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opasich C, Cafiero M, Scherillo M, et al. Impact of diabetes on the current in-hospital management of heart failure. From the TEMISTOCLE study. Ital Heart J. 2003;4(10):685–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roe-Prior P. Sociodemographic variables predicting poor post-discharge outcomes for hospitalized elders with heart failure. Medsurg Nurs. 2007;16(5):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rathore S, Foody J, Wang Y, et al. Race, quality of care, and outcomes of elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure.[see comment] JAMA. 2003;289(19):2517–2524. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kociol RD, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, et al. Long-term outcomes of medicare beneficiaries with worsening renal function during hospitalization for heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(12):1786–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez F, Joynt KE, Lopez L, Saldana F, Jha AK. Readmission rates for Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2011;162(2):254–261.e253. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aranda JM, Jr, Johnson JW, Conti JB. Current trends in heart failure readmission rates: analysis of Medicare data. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(1):47–52. doi: 10.1002/clc.20453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luthi J, Lund M, Sampietro-Colom L, Kleinbaum D, Ballard D, McClellan W. Readmissions and the quality of care in patients hospitalized with heart failure. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(5):413–421. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krumholz H, Parent E, Tu N, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. [see comment] Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(1):99–104. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440220103013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K. Does oxygen saturation or distance walked predict rehospitalization in heart failure? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23(4):349–356. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317434.29339.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Philbin E, Dec G, Jenkins P, DiSalvo T. Socioeconomic status as an independent risk factor for hospital readmission for heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(12):1367–1371. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)01554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rathore S, Masoudi F, Wang Y, et al. Socioeconomic status, treatment, and outcomes among elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the National Heart Failure Project. Am Heart J. 2006;152(2):371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsuchihashi M, Tsutsui H, Kodama K, et al. Medical and socioenvironmental predictors of hospital readmission in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 2001;142(4):E7. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albert NM, Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, et al. Depression and clinical outcomes in heart failure: an OPTIMIZE-HF analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122(4):366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Struthers A, Anderson G, Donnan P, MacDonald T. Social deprivation increases cardiac hospitalisations in chronic heart failure independent of disease severity and diuretic non-adherence. Heart. 2000;83(1):12–16. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chioncel O, Vinereanu D, Datcu M, et al. The Romanian Acute Heart Failure Syndromes (RO-AHFS) registry. Am Heart J. 2011;162(1):142–153.e141. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saczynski JS, Darling CE, Spencer FA, Lessard D, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Clinical features, treatment practices, and hospital and long-term outcomes of older patients hospitalized with decompensated heart failure: The Worcester Heart Failure Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1587–1594. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feinglass J, Martin G, Lin E, Johnson M, Gheorghiade M. Is heart failure survival improving? Evidence from 2323 elderly patients hospitalized between 1989–2000. Am Heart J. 2003;146(1):111–114. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garty M, Shotan A, Gottlieb S, et al. The management, early and one year outcome in hospitalized patients with heart failure: a national Heart Failure Survey in Israel–HFSIS 2003. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9(4):227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting Mortality Among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure: Derivation and Validation of a Clinical Model. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2581–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldberg R, Spencer F, Farmer C, Meyer T, Pezzella S. Incidence and hospital death rates associated with heart failure: a community-wide perspective. Am J Med. 2005;118(7):728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuccala G, Pedone C, Cesari M, et al. The effects of cognitive impairment on mortality among hospitalized patients with heart failure.[see comment] Am J Med. 2003;115(2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pearson M, Kahn K, Harrison E, et al. Differences in quality of care for hospitalized elderly men and women. JAMA. 1992;268(14):1883–1889. doi: 10.1001/jama.1992.03490140091041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ni H, Nauman D, Hershberger R. Managed care and outcomes of hospitalization among elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(11):1231–1236. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.11.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fonarow G, Abraham W, Albert N, et al. Factors identified as precipitating hospital admissions for heart failure and clinical outcomes: findings from OPTIMIZE-HF. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(8):847–854. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ambardekar AV, Fonarow GC, Hernandez AF, et al. Characteristics and in-hospital outcomes for nonadherent patients with heart failure: findings from Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) Am Heart J. 2009;158(4):644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zuluaga MC, Guallar-Castillon P, Conthe P, et al. Housing conditions and mortality in older patients hospitalized for heart failure. Am Heart J. 2011;161(5):950–955. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Torres J, Cardenas O, Vasquez A, Schlossberg D. Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia in a community hospital.[see comment] Chest. 1998;113(2):387–390. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bohannon R, Maljanian R. Hospital readmissions of elderly patients hospitalized with pneumonia. Conn Med. 2003;67(10):599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.El Solh A, Pineda L, Bouquin P, Mankowski C. Determinants of short and long term functional recovery after hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: role of inflammatory markers. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vinson J, Rich M, Sperry J, Shah A, McNamara T. Early readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure.[see comment] J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(12):1290–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Afzal A, Ananthasubramaniam K, Sharma N, et al. Racial differences in patients with heart failure. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(12):791–794. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krumholz H, Chen Y, Wang Y, Vaccarino V, Radford M, Horwitz R. Predictors of readmission among elderly survivors of admission with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2000;139(1 Pt 1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(00)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen M, Chang H, Cheng C, Chen Y, Chai H. Risk stratification of in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for chronic congestive heart failure secondary to non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Cardiology. 2003;100(3):136–142. doi: 10.1159/000073931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Formiga F, Chivite D, Sole A, Manito N, Ramon J, Pujol R. Functional outcomes of elderly patients after the first hospital admission for decompensated heart failure (HF). A prospective study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;43(2):175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luttik M, Jaarsma T, Veeger N, van Veldhuisen D. Marital status, quality of life, and clinical outcome in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2006;35(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K. Effect of gender, ethnicity, pulmonary disease, and symptom stability on rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(7):1139–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Najafi F, Dobson A, Jamrozik K. Recent changes in heart failure hospitalisations in Australia. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(3):228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Sokos G, et al. Gender differences in patients admitted with advanced decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(4):454–458. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lofvenmark C, Mattiasson A-C, Billing E, Edner M. Perceived loneliness and social support in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8(4):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moser DK, Yamokoski L, Sun JL, et al. Improvement in health-related quality of life after hospitalization predicts event-free survival in patients with advanced heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15(9):763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muus KJ, Knudson A, Klug MG, Gokun J, Sarrazin M, Kaboli P. Effect of post-discharge follow-up care on re-admissions among US veterans with congestive heart failure: a rural–urban comparison. Rural Remote Heal. 2010;10(2):1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akosah K, Schaper A, Haus L, Mathiason M, Barnhart S, McHugh V. Improving outcomes in heart failure in the community: long-term survival benefit of a disease-management program. Chest. 2005;127(6):2042–2048. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Mas J-L, et al. Three-year follow-up and event rates in the international Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health Registry. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(19):2318–2326. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]