Abstract

Anthrax is a zoonotic disease caused by Bacillus anthracis. It is potentially fatal and highly contagious disease. Herbivores are the natural host. Human acquire the disease incidentally by contact with infected animal or animal products. In the 18th century an epidemic destroyed approximately half of the sheep in Europe. In 1900 human inhalational anthrax occured sporadically in the United States. In 1979 an outbreak of human anthrax occured in Sverdlovsk of Soviet Union. Anthrax continued to represent a world wide presence. The incidence of the disease has decreased in developed countries as a result of vaccination and improved industrial hygiene. Human anthrax clinically presents in three forms, i.e. cutaneous, gastrointestinal and inhalational. About 95% of human anthrax is cutaneous and 5% is inhalational. Gastrointestinal anthrax is very rare (less than 1%). Inhalational form is used as a biological warefare agent. Penicillin, ciprofloxacin (and other quinolones), doxicyclin, ampicillin, imipenem, clindamycin, clarithromycin, vancomycin, chloramphenicol, rifampicin are effective antimicrobials. Antimicrobial therapy for 60 days is recommended. Human anthrax vaccine is available. Administration of anti-protective antigen (PA) antibody in combination with ciprofloxacin produced 90%-100% survival. The combination of CPG-adjuvanted anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA) plus dalbavancin significantly improved survival.

Keywords: Anthrax, Bacillus anthracis, Zoonotic disease, Contagious disease, Cutaneous anthrax, Inhalational anthrax, Gastrointestinal anthrax, Human anthrax

1. Introduction

The term “anthrax” derives from the Greek word “anthrakites” meaning coal-like referring to the typical black eschar seen in cutaneous involvement of the disease[1]. Anthrax is a zoonotic infection with world wide distribution. It is a potentially fatal and highly contagious disease. The causative bacteria is Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis). Herbivore animals are the natural host of the disease and all warm blooded animals are susceptible. Human acquire the disease incidentally by contact with infected animal or animal products or by ingestion or handling of the infected animal meat. Anthrax can be transmitted from animal to animal or from animal to human. No human to human transmission has been documented. Anthrax endospores are resistant to drying, heat, ultraviolet light, gamma radiation and many disinfectants[2],[3]. The spores can persist in dry soil for decades but can be destroyed by boiling in water for 10 minutes. Grazing animals often swallow these spores which develop into the encapsulated vegetative mature bacilli in the circulation[4].

The disease has cutaneous, inhalational and gastrointestinal forms, which occur when endospores enter the body through breaks in the skin or by inhalation or by ingestion, respectively. About 95% of human anthrax is cutaneous and 5% inhalational. Gastrointestinal anthrax is very rare and has been reported in less than 1% of all cases. Anthrax meningitis is a rare complication of any of the other three forms of the disease. Inhalational anthrax become known in Victorian England as woolsorters' disease. This was because of the frequency of infection in mill workers exposed to animal fibers contaminated with B. anthracis spore[1],[4].

In 1850 Pierre Raver and Casimir Joseph Davaine discovered the microorganism causing anthrax. In 1876 Robert Koch first described the complete life cycle of the anthrax bacillus. In 1881 Louis Pasteur developed the first animal vaccine containing attenuated live organism. Human anthrax vaccine was licensed in 1970[1],[5]. Anthrax continued to represent a world wide presence with an annual occurrence of 20 000-100 000 cases in the first half of the 20th century and subsequently the incidence declined with approximately 2 000 cases yearly during the second half of the 20th century. The majority of these cases were cuteneous anthrax[6]. In the whole 20th century there was only 18 cases of human inhalational anthrax reported in the United States, of these 16 was fatal. No cases of gastrointestinal form had been reported[1],[7].

This review article describes the update of anthrax. Anthrax can reemerge infrequently in some area of the world leading to death of many animals and human. There is also apprehension of it's use as biological warfare. So this review article will be useful for clinicians to suspect and manage a case of anthrax.

2. History of anthrax

Anthrax is a potentially fatal and highly contagious zoonotic disease. Anthrax can be transmitted from animal to animal or from animal to human. No human to human transmission has been documented[2],[3]. It is an illness well described in antiquity. There have been suggestions that the famous plaque of Athens (430-427 BCE) was an epidemic of inhalational anthrax. Anthrax continued to be a pestilence affecting both human and animal throughout the middle ages. In the 18th century an epidemic destroyed approximately half of the sheep in Europe. Inhalational anthrax becomes known to Victoriam England as Woolsorters' disease. This was because of the frequency of infection in mill workers exposed to animal fibers contaminated with B. anthracis spores, though it was a misnomer in the sense that infection was more often the result of contact with goat hair or alpaca than wool.

The 19th century was to find anthrax as the focal point of one of the central development in the history of medicine. In 1850 Pierre Raver and Casimir Joseph Davaine discovered small filiform bodies about twice the length of a blood corpuscle in the circulation of sleep with anthrax. Although there is no evidence that they initially regarded these as being significant, they were subsequently to find the organisms consistently in animals with the disease. Davaine suggested that because of the presence of the bacilli in the blood of affected animals it was conceivable that these microorganisms were causing the disease rather than the products of diseased tissue, as was then accepted thinking[1]. Anthrax was studied extensively in the 1870s by several researchers including Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur. In 1876 Koch used suspended drop culture method to trace the complete life cycle of the anthrax bacillus for the first time. He found that the bacillus could form spores that remained viable for long period in adverse environment. He also stated that anthrax could only be transmitted from one host to another by transfer of the bacilli. In the following year Koch grew the organism in vitro and induced the disease in healthy animals by inoculating them with bacterial cultures. Anthrax was thus the prototype for Koch's famous postulates regarding the transmission of infections disease. In 1881 Louis Pasteur developed the first animal anthrax vaccine containing attenuated live organisms. In the early 1900s human cases of inhalational anthrax occurred in the United States, among which were workers in textile and tanning industries processing goat hair, goat skin or wool[5]. The incidence of the disease was decreased significantly during the 20th century. Among animal workers, this was postulated to be due to vaccination as well as improved animal husbandry and processing of animal products. Anthrax continued to represent a world wide presence outside the United States, with an annual occurrence of 20 000-100 000 cases in the first half of the 20th century and approximately 2 000 cases yearly during the second half. The majority of these cases were cutaneous[6]. A human anthrax vaccine was developed by the army chemical corps in the 1950 and this was replaced by a vaccine licensed in 1970[6]. In the whole 20th century there was only 18 cases of human inhalational anthrax reported in United States, of these 16 was fatal. No cases of gastrointestinal form had been reported[2]. There occured an outbreak among livestock in Sverdlovsk near a Soviet Microbiology Facility in 1979, with some of the surrounding population subsequently developing gastrointestinal anthrax after eating contaminated meat or cutaneous anthrax after contact with diseased animal. This outbreak caused 96 cases of human anthrax, of these 79 were said to be gastrointestinal (of which 64 were fatal) and the remainder cutaneous. This epidemic represented the largest documented outbreak of human anthrax in history. In October and November 2001, 22 cases of confirmed or suspected inhalational and cutaneous anthrax were reported associated with the intentional release of the organism in the United States. An additional cases of cutaneous disease occurred in March of 2002[1].

Potential for use of anthrax as an agent of biological warfare has existed since world war II when investigation was done regarding anthrax along with several other infectious agents for use as biological weapons. Characteristics of anthrax that make it a good biological weapon are low visibility, high potency, relatively easy delivery, accessibility and its ability to form spores that are resistant to drying[8].

3. Description of microorganism

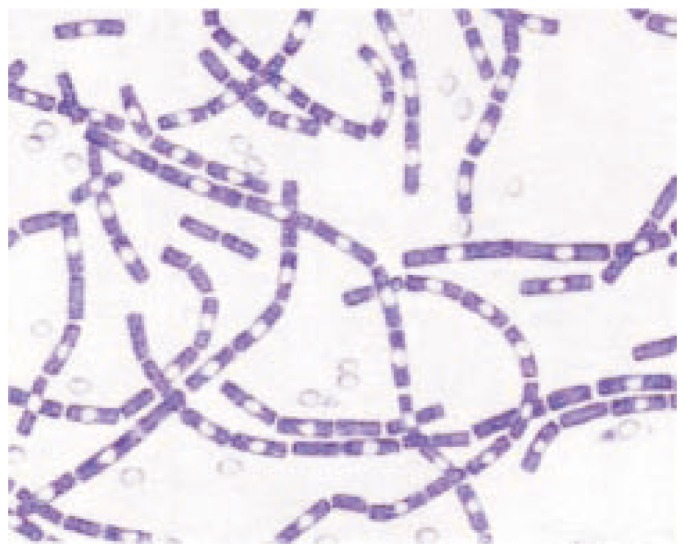

B. anthracis is the causative pathogenic organism of anthrax (Figure 1). This large, aerobic, Gram-positive rod (1-1.5 µm by 3-10 µm) is a member of the Bacillus cereus group of Bacilli. Mucoid colonies are formed when cultured on standard blood or nutrient agar. Endospores are seen in 2 to 3 days old cultures. B. anthracis is non-motile and non-haemolytic on blood agar. In vitro the organism exist as single or in short chains but form long chains in vivo. B. anthracis has two major virulence factors, which are encoded on separate plasmids. Plasmid X01 codes for the three proteins i.e. protective antigen (PA), edema factor (EF) and lethal factor (LF), that make up two exotoxins. PA is the central component of both toxins. PA binds to target cell receptors and provides a means for EF and LF to enter the cell. PA plus EF together make up oedema toxin and PA plus LF combine to form lethal toxin. Edema toxin leads to loss of chloride ions and water from the cell and subsequent formation of massive edema in surrounding tissue. Edema toxin has a secondary role in inhibiting the phagocytic and oxidative burst activity of neutrophils. LF is a zinc metalloprotease. It causes increased expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) inside the macrophages. Subsequently it causes lysis of macrophages with release of inflammatory mediators. The lethal toxin dependent release of TNF and IL-1 is the major cause of death in infected animal and human[8].

Figure 1. Characteristics of B. anthracis. Gram stain (1 500×).

The cells have characteristic squared ends. The endospores are ellipsoidal shaped and located centrally in the sporangium. The spores are highly refractile to light and resistant to staining.

4. Clinical manifestation of anthrax

Anthrax occurs in three major clinical forms i.e. cutaneous, gastrointestinal and inhalational anthrax. About 95% of human anthrax is cutaneous and 5% is inhalational. Gastrointestinal anthrax is very rare and has been reported in less than 1% of all cases[4],[9].

4.1. Cutaneous anthrax

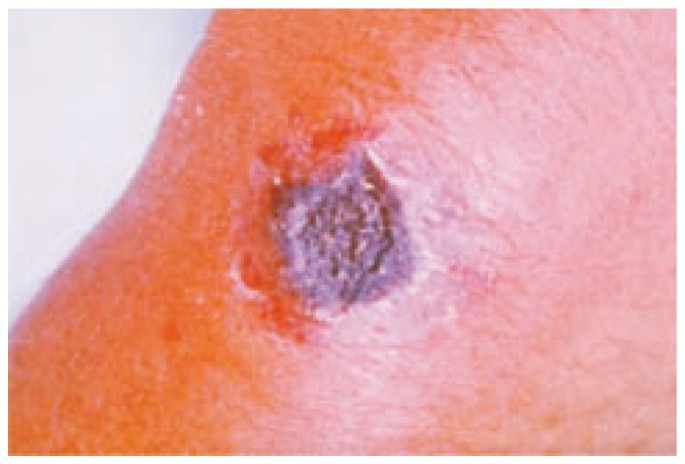

It is the most common form accounting for 95% of naturally occuring cases of anthrax. Disease usually results from the occupational exposure of human to infected animal or animal products. Any exposed area of the skin may be affected, most commonly in the arm, hand, head or neck. The organisms are inoculated through a break in the skin. Incubation period ranges from 1 to 12 days. The primary skin lesion appears as a painless pruritic papule usually 3 to 5 days after exposure. These papules enlarge over 1 to 2 days to form an ulcer. The ulcer is usually 1 to 3 cm in diameter with round regular border. Vesicles may surround the ulcer over the next several days. Necrosis and drying of the ulcer lead to the formation of characteristic depressed black eschar (Figure 2). The lesion is not purulent unless a superinfection is present. The eschar separates in 1 to 2 weeks and falls off leaving a scar in most cases. The eschar is surrounded by oedema which may be severe. If the lesion is on the head or neck, respiratory compromise may occur as a result of massive edema. Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise and headache are often present along with regional lymphadenopathy. Cases of temporal arteritis and corneal scaring have been reported. Death occurs in about 20% of untreated cases and in less than 1% of cases with antibiotic treatment[10],[11].

Figure 2. The black eschar present in the cutaneous anthrax.

4.2. Gastrointestinal (GI) anthrax

Most of the gastrointestinal anthrax cases occur in developing countries when disease results from the consumption of inadequately cooked meat from sick or dead animals[11]. GI anthrax occurs in two different clinical forms: oropharyngeal and intestinal. Incubation period for both forms is typically between 1 to 7 days[4]. Oropharyngeal anthrax is an uncommon variant of GI anthrax. This form often has a more favorable prognosis. Some patients die from respiratory distress or sepsis. Ulcers are present at the base of the tongue, posterior wall of oropharynx (pseudomembranous ulceration). Clinical Manifestations are fever, dysphagia, respiratory distress, regional lymphadenopathy and marked neck swelling. In intestinal anthrax lesion usually occurs in the caecum often accompanied by haemorrhagic lymphadenitis in the abdomen. Initial symptoms are non-specific often leading to delayed diagnosis. Patient often develops fever, anorexia, vomiting, severe pain in the abdomen, haematemesis, severe bloody diarrhoea and progressive ascites. Diagnosis is rarely made before death except in endemic areas. Death occurs in 2 to 3 days as a result of bowel perforation, shock and toxemia. Mortality rate of intestinal anthrax is 25%-60% and may even reach 100%[4],[10],[11].

4.3. Inhalational anthrax

Inhalational anthrax is a deadly form of anthrax caused by inhalation of pathogenic endospores. The incubation period is from 1 to 7 days, varing from 2 days to 6 weeks, maybe longer up to 60 days, depending on the size of the inoculum and the immune status of the host. The lethal dose for human is approximately 8 000 to 10 000 spores. A case fatality rate of 86% was reported following 1979 outbreak in the former Soviet Union and a case fatality rate of 89% was reported for inhalational anthrax in the United States [10]–[12].

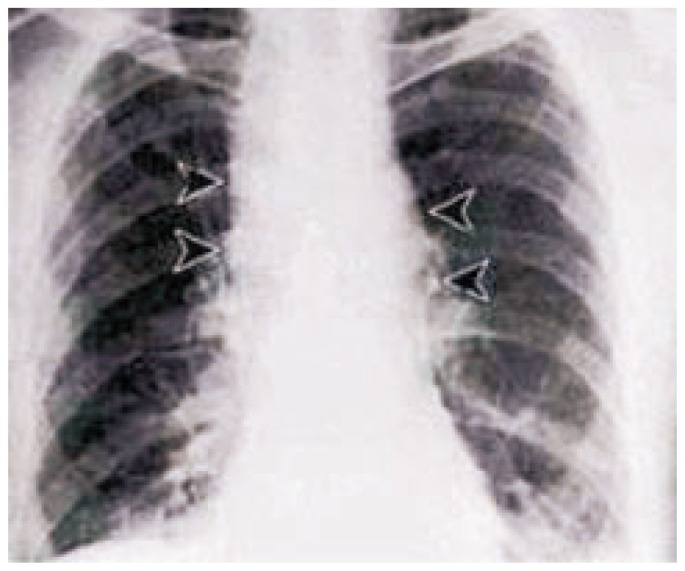

Once inside the lung, spores are engulfed by alveolar macrophages and transported to mediastinal and peribronchial lymph nodes. Spore can germinate into vegetative bacilli within the lymph nodes. The rapid multiplication of bacilli results in haemorrhagic mediastinitis, followed by haematogenous spread throughout the body. Clinical disease follows a characteristic biphasic pattern. Initial symptoms resemble an upper respiratory infection. Over the first 1 to 3 days the patients develop malaise, fatigue, non-productive cough, precordial pressure and fever. There may be a transient improvement of symptoms before the second phase of illness which is because of release of TNF and IL-1 from the macrophages leading to rapidly deteriorating clinical picture. The second phase of the disease is characterized by acute dyspnoea, stridor and hypoxaemia as a result of tracheal compression by enlarged lymph nodes. Patient often develop cyanosis, diaphoresis and fever or hypothermia due to sepsis. Other common symptoms include abdominal pain, delirium, meningism, haematemesis and melena. In the late stage mediastinal haemorrhage, septic shock and coma may develop. There may be pneumonia, pleural effusion and widening of the mediastinum due to enlarged lymphnodes (Figure 3). If pneumonia is present, a local haemorrhagic necrotizing lesion occurs in the lung parenchyma. Thoracocentesis occasionally reveals grossly bloody fluid. Once a patient reaches the second phase of the disease, death usually occurs from septic shock in 1 to 2 days even with adequate antibiotic therapy.

Figure 3. Widening of the mediastinum due to enlarged lymphnodes.

4.4. Anthrax meningitis

It is a rare complication of the three forms of the disease. Meningeal infection results from haematogenous or lymphatic spread of the bacilli to the central nervous system and meninges. Clinical features include fever, neck rigidity, headache, seizure, agitation and delirium. Pathologic findings are haemorrhagic meningitis and bloody cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) containing inflammatory infiltrates and large number of bacilli. Autopsy reveals dark red meninges that have been called the “Cardinals cap”. Anthrax meningitis is almost always fatal within 1 to 6 days even with antibiotic therapy[4],[8].

5. Investigations

Gram stain of any tissue or fluid will reveal large number of the bacilli. B. anthracis can be cultured on sheep's blood agar from blood, ascitic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural effusion or skin lesion. Blood culture is almost always positive. Culture of skin lesion is positive in only 60% to 65% of cases. Nasal swab culture is investigational. Antibiotic susceptibility testing should be done on all isolates, specially if biological warfare or terrorism is a possibility. Because strains can be mutated to be resistant to some antibiotics. Serological diagnosis is possible but most useful retrospectively because acute and convalescent samples are needed. An enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is available. Quadrupling of antibody titres directed towards capsular antigen indicate past infection or vaccination. The anthrax skin test performed by subdermal injection of an attenuated strain can diagnose acute or prior infection. The test is positive in 82% of cases 1 to 3 days after the onset of symptoms and in 99% of cases at the end of 4 weeks. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can amplify specific markers of B. anthracis or of the Bacillus cereus group and specific virulence plasmid markers carried by different strain[8].

6. Treatment of anthrax

B. anthracis is susceptible to penicillin, fluroquinolones, ampicillin, erythromycin, clarithomycin, doxicyclin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, first-generation cephalosporin, vancomycin, clindamycin and imipenem. Ciprofloxacin and other quinolones such as ofloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin have similar success in the treatment and prevention of anthrax[13]. The organism is resistant to third-generation cephalosporin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Antimicrobial susceptibility test should be done for all cases and therapy should be adjusted accordingly[9]. Antimicrobial resistance may develop during therapy as was suggested in study[14]. Uncomplicated cutaneous anthrax can be treated with penicillin-v 250 to 500 mg orally four times a day for 7 to 10 days[8]. If it is associated with simultaneous aerosol exposure, a potential for reactivation of latent infection may exist, then the case should be treated for 60 days[11]. Ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally 12 hourly (also other quinolones) and doxicyclin 100 mg orally 12 hourly are also first line therapy for cutaneous anthrax[15],[16]. Intravenous therapy with multiple drugs is recommended for cutaneous anthrax with signs of systemic involvement, such as extensive oedema or lesions on the head and neck region. Ciprofloxacin 400 mg i.v. 12 hourly or doxicyclin 100 i.v. 12 hourly can be used. Antimicrobial treatment may make the skin lesion culture negative in 24 hours. However, eschar formation still occurs[13]. Excision of eschar is contraindicated because of risk of haematogenous dissemination of the bacilli. Topical therapy is not effective. In all other forms of anthrax (inhalational or gastrointestinal including anthrax meningitis) antibiotics should be administered intravenously (i.v.) in an intensive care unit. The drug of choice is penicillin G 4 million units i.v. 4 to 6 hourly. Streptomycin may have a synergestic effect with penicillin and may be given concurrently. Doxicyclin 200 mg i.v. followed by 100 mg i.v. 12 hourly or ciprofloxacin 400 mg i.v. 12 hourly is effective. Supportive therapy is important to prevent septic shock. Fluid and electrolyte balance is to be maintained. Airway patency should be ensured[8].

Because of toxin mediated morbidity corticosteroid has been suggested as adjunct therapy for inhalational anthrax associated with extensive oedema, respiratory compromise and meningitis[15]. Corticosteroid should also be considered for extensive oedema or swelling of the head and neck region in cutaneous anthrax[11].

7. A single dose combination therapy that prevents and treats anthrax

Exposure to B. anthracis leads susceptible host at prolonged risk of infection since spores can persist in vivo for months before germinating to cause life threatening disease. Anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA, the licensed US vaccine) induces immunity too slowly to protect susceptible individual post exposure. Antibiotics prevent the proliferation of vegetative bacilli but do not block latent spores from germinating. Thus anthrax exposed individuals must remain on antibiotic therapy for months to eliminate the threat posed by delayed spore germination. Unfortunately long term antibiotic treatment is poorly tolerated and frequently discontinued by the patient. Currently study was done to overcome this problem in anthrax treatment. Studies in mice, rhesus macaques and human showed that the protection induced by anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA) can be accelerated and magnified by the addition of CPG oligonucleotide (OGN) as adjuvant. Dalbavancin is an injectable long acting lipoglycopeptide antibiotic. Dalbavancin effectively targets Gram positive bacteria including B. anthracis and has a much longer half life than ciprofloxacin. Thus a single dose of dalbavancin can protect an exposed animal for weeks rather than days providing sufficient time for the co-administered CPG adjuvanted AVA to induce a durable protective immunity. The combination of CPG adjuvanted AVA plus dalbavancin significantly improved survival when administered up to 3 days post exposure of B. anthracis spore. However, efficacy was lost if treatment was delayed[17],[18]. Dalbavancin combined with CPG-adjuvanted AVA significantly reduced the risk from both immediate and delayed germination of anthrax spores[19]. Vietri et al demonstrated that rhesus macaques challenged with anthrax were protected if vaccinated with AVA within 2 hours of infection and then treated for 2 weeks with oral ciprofloxacin[20].

8. Treatment of anthrax with combination of antibodies to protective antigen (PA) of B. anthracis and ciprofloxacin

There is a need for new safe and effective treatment to supplement antibiotic therapy. Simultaneous inhibiton of lethal toxin action with antibodies and blocking of bacterial growth by antibiotic will be beneficial for the treatment of anthrax. Study was done using combination of rabbit or sheep anti protective antigen (PA) antibodies IgG and ciprofloxacin in rodent anthrax. This study revealed 90%-100% survival rate[21]. Anti-PA antibody is protective when administered within 24 hours of anthrax challenge[22].

9. Post exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis is indicated to prevent inhalational anthrax after a confirmed or suspected exposure to anthrax aerosol. Initial therapy with ciprofloxacin or doxicyclin is recommended for adults and children. Other quinolones can also be used with similar success[23]. Penicillin is also approved by FDA. The use of amoxicillin in three daily doses is an option for children and pregnant or lactating females[24]. Duration of 60 days or 100 days antibiotic prophylaxis plus anthrax vaccination is recommended[25].

10. Prevention of anthrax by vaccination

Human anthrax vaccine is available. The vaccine is produced from protective antigen (PA) of attenuated non-encapsulated strain of B. anthracis, that is alum precipitated to form the vaccine. Individuals at high risk of occupational exposure such as laboratory workers and veterinarians in areas with a high incidence of anthrax should receive the vaccine[26]. Vaccination is given at 0, 2 and 4 weeks, then at 6,12 and 18 months, followed by yearly boosters. Post exposure vaccination is recommended at 0, 2 and 4 weeks.

Adverse reactions to the vaccine are relatively rare and usually mild. The incidence of mild and moderate local reactions are 30% and 4%, respectively. The vaccine should be administered only if the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks. Studies are not available regarding the use of anthrax vaccine in pregnant women. The anthrax vaccine is not contraindicated during breast feeding. The ability of vaccination to protect human in the event of biological warfare is unknown. New vaccines are being studied. Live vaccine based on anthrax strain with auxotrophic mutations may become available. Another promising preparation contains protective antigen from recombinant sources, combined with adjuvants from the cell wall of the BCG strain of the tubercle bacilli to increase the cellular response. Specific inhibitory drugs directed toward the zinc metalloprotease of lethal factor are under development and may be available in the near future[27].

11. Conclusion

Anthrax is a virulent and highly contagious disease. Death rate is also very high. The causative organism is sensitive to many antimicrobial agents. But duration of antibiotic treatment is long up to 60 days or 100 days. Early suspicion and diagnosis is essential for improved survival of the patient. Treatment continuation for long period is a problem. So development of new therapeutic agent to overcome this problem is essential. Bioterrorism should be stopped.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stembach G. The history of anthrax. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:463–467. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(03)00079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon IC, Mesclson M, Guillemin J, Hanna PC. Anthrax. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:815–826. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909093411107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and practice of infectious disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 2000. pp. 2215–2220. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babamahmoodi F, Aghabarari F, Arjmand A, Ashrafi GH. Three rare cases of anthrax arising from the same source. J Infect. 2006;53:175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jernigan JA, Stephens DS, Ashford DA, Omenaca C, Topiel MS, Galbraith M, et al. et al. Bioterrorism related inhalational anthrax the first 10 cases reported in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:933–944. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris K. US military face punishment for refusing anthrax vaccine. Lancet. 1999;353:130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brachman PS. Bioterrorism: an update with a focus on anthrax. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:981–987. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamie WE. Anthrax: diagnosis, treatment, prevention. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 2002;9:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swartz M. Recognition and management of anthrax: an update. Current concepts. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1621–1626. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inlesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Friedlander AM, et al. et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 1999;281:1735–1745. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.18.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brook I. The prophylaxis and treatment of anthrax. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;20:320–325. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas CN. On the risk of mortality to primates exposed to anthrax spores. Risk Anal. 2002;22:189–193. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon IC, Mesclson M, Guillemin J, Hanna PC. Anthrax. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:818–826. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909093411107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broak I, Elliott IB. In vitro resistance of Bacillus anthracis to doxicyclin, macrolides and quinolones. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00464-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Additional options for preventive treatment for persons exposed to inhalational anthrax. MMWR Wkly Rep. 2001;50:1142–1151. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Interim guidelines for investigation of and response to Bacillus anthracis exposure. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Streit JM, Fritsche TR, Sader HS, Jones RN. World wide assessment of dalbavancin activity and spectrum against over 6000 clinical isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;48:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leighton A, Gattlieb AB, Dorrr MB, Jabes D, Moscooni G, Vansaders C, et al. et al. Tolerability, pharmacokinetics and serum bactericidal activity of intravenous dalbavancin in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:940–945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.940-945.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klinmon DM, Tross D. A single dose combination therapy that both prevents and treats anthrax infection. Vaccine. 2009;27:1811–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vietri NJ, Purcell BK, Lawler JV, Leffel EK, Rico P, Gamble CS, et al. et al. Short course post exposure antibiotic prophylaxis combined with vaccination protects against experimental inhalational anthrax. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7813–7816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karginov VA, Robinson TM, Riemenschneider J, Golding B, Kennedy M, Shiloach J, et al. et al. Treatment of anthrax infection with combination of ciprofloxacin and antibodies to protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:71–74. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00302-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitale L, Blanset D, Lowy I, O'Neill I, Goldstein J, Little SF, et al. et al. Prophylaxis and therapy of inhalational anthrax by a novel monoclonal antibody to protective antigen that mimics vaccine induced immunity. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5840–5847. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00712-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Food and Drug Administration Prescription drug products, doxiycline and penicillin G procaine administration for inhalational anthrax (Post exposure) Fed Reg. 2001;66:55679–55682. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Use of anthrax vaccine in the United States recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;15:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inglesby TV, O'Toole P, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, et al. et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002 update recommendations for management. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;287:2236–2252. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashford DA, Rotz LD, Perkins B. Use of anthrax vaccine in the United States. Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR. 2000;49:15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran G, Talan D, Pinner R. CDC update: update on emerging infections from the centre for disease control and prevention. Bioterrorism alleging use of anthrax and interim guidelines from management-United States, 1998. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]