Abstract

We introduce a method to follow DNA repair that is suitable for both clinical and laboratory samples. An episomal construct with a unique 8-oxoguanine base at a defined position was prepared in vitro using single-stranded phage harboring a 678 bp tract from exons 5–9 of the human P53 gene. Mixing curve experiments showed that the real-time PCR method has a linear response to damage, suggesting that it is useful for DNA repair studies. The episomal construct with a unique 8-oxoguanine was introduced into AD293 cells or human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and plasmids recovered as a function of time. The quantitative real-time PCR assay demonstrated that repair of the 8-oxoguanine was 80% complete in under 48 hours in AD293 cells. Transfection of siRNAs down regulated expression OGG1 in AD293 cells and reduced the repair of 8-oxoguanine to 30%. Transfection of the episome into unstimulated white blood cells and showed that 8-oxoguanine repair had a half-life of from 2–5h. This method is a rapid, reproducible, and robust way to monitor repair of specific adducts in virtually any cell type.

Keywords: DNA damage, oxidative damage, 8-oxoguanine, strand-specific repair, siRNA

Introduction

Exogenous and endogenous agents constantly inflict DNA damage [1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7], and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a major source of endogenous damage [6; 8]. ROS form a number of damaged bases, but one of the most diagnostic bases for this type of damage is 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) [9; 10]. When 8-oxoG is in DNA it miscodes for adenine producing G→T transversion mutations when DNA synthesis occurs [11; 12; 13] and mice lacking 8-oxoG and MYH develop tumors [14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 19; 20]. In addition, accumulation of 8-oxoG has been associated with lung tumors that could arise due to DNA repair defects [21; 22].

To eliminate 8-oxoG and its significant consequences, cells have evolved repair systems to eliminate damage and prevent genotoxicity [23; 24]. Base excision repair (BER) is a major factor in the repair of 8-oxoG [25; 26; 27; 28; 29; 30; 31]. In human cell extracts in vitro, OGG1 is the major DNA glycosylase that excises 8-oxoG and initiates the BER pathway [29; 32; 33]. But 8-oxoG can also be repaired to a lesser extent by a series of DNA glycosylases known as NEIL1, 2, or 3 [29; 34; 35; 36]. Despite the fact that OGG1 plays a major role in excising 8-oxoG, OGG1 only excises 8-oxoG from the non-transcribed strand of transcribed genes [37; 38]. In vitro nucleotide excision repair (NER) assays show that 8-oxoG is subject to excision, consistent with recognition by that repair system [39]. There is also evidence that mismatch repair could be involved in the removal of 8-oxoG adducts [40; 41]. Therefore, a number of DNA repair pathways could have a role in the eradication of 8-oxoG to limit possible genotoxic effects.

One obstacle to the study of DNA repair of oxidative damage in mammalian systems is that it is pleiotropic, reacting with not only DNA, but also with proteins and membranes [20; 42; 43]. Despite the fact that the number of adducts produced by oxidative damage is large, progress has been made toward elucidating how repair occurs in cells. Repair of oxidative damage can be monitored using numerous techniques including mass spectrometry, PCR, or alkaline elution [44; 45; 46; 47]. All of those techniques monitor DNA damage in cells, but the wide range of targets for oxidative damage can obscure the role of DNA repair leading to mutation. Targeted deletion or siRNA depletion, which either obliterates or reduces OGG1 expression in mouse or human cells, has shed light on the role of OGG1 in preventing mutation [16; 19; 48; 49; 50; 51; 52; 53]. Another useful assay, based on OGG1 activity in cell extracts, has also provided interesting data [54; 55].

One way to monitor damage directly in cells is through host cell reactivation assays that have been used to follow repair of several types of DNA damage in stimulated lymphocytes or lymphoblasts [56; 57; 58; 59; 60; 61; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66]. Differences in normal and NER deficient cells have been detected using this method. These assays are useful, but generally the plasmids are modified in vitro with DNA damaging agents and therefore repair is observed only indirectly by monitoring an enzymatic activity such as chloramphenicol acetyltransferase or luciferase. Nonetheless, these techniques can be used to investigate larger populations, but are limited in providing details about DNA repair at the molecular level and the adducts removed from the DNA, since the assay is based on the protein produced and therefore requires the disruption of the transcribed coding sequence or promoter.

Instead of subjecting cells to oxidative damage at a global level or by introduction of globally damaged plasmid by transfection, another way to study DNA repair is through the use of episomal vectors that can be isolated from mammalian cells and then probed for repair. We can insert specific modified bases at defined sites and monitor DNA repair or mutagenesis [67; 68; 69; 70; 71; 72; 73]. To determine repair kinetics, a non-replicating episome is transfected into mammalian cells and then the closed circular episomal DNA is harvested. One method to evaluate repair of site specific adducts uses Southern blotting [37; 74]. There are definite advantages to using Southern blotting to monitor DNA repair at a specific site, but it is still more difficult to examine replicate samples. Therefore, the capacity to monitor repair of a unique adduct in episomal DNA reproducibly would allow researchers to follow the kinetics for the elimination of damage in small populations (10–100 persons). This would yield information on the specific defects in DNA repair systems.

In this report, we demonstrate a simple method to follow DNA repair of episomal DNA in any type of cells. This real time PCR-based method is rapid and reproducible compared to existing methods. It should have applications to the field of DNA repair and be useful in the determination of defects in human cells. To show its utility, we have measured repair of 8-oxoG adducts in both cell lines and in normal, unstimulated human lymphocytes. Therefore, this assay could be used to monitor DNA repair in patient samples. We have also used siRNA to knock down the production of OGG1 in human cells and show that this method is suitable for examination of repair of 8-oxoG in non-transcribed DNA.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and enzymes

Oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODNs) were obtained from IDT or Midland. All modified 8-oxoG ODNs were verified using MALDI. siRNAs were prepared using the Silencer pre-designed siRNA kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). All ODNs and siRNAs used in this study are indicated in Table 1. Fpg was obtained from laboratory stocks and used as described [75; 76; 77]. RB69 DNA polymerase expression vector was a kind gift from Dr. William Konigsberg (Yale University, New Haven, CT) and the DNA polymerase was purified using established protocols [78; 79; 80]. T4 DNA ligase was obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) or was cloned and purified in the laboratory as described below. Pfu DNA polymerase was purified from an overexpressing clone prepared by Bin Wang in the laboratory using established methods. T4 polynucleotide kinase was obtained from Roche Biochemicals. γ-[32P]-ATP was obtained from ICN Biochemicals. The OGG1 antibody was obtained from Drs. Pablo Radicella and Serge Boiteux (CNRS-CEA, Fontenay-aux Roses, France) and the tubulin antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The M13mp18-P53 was prepared by insertion of a 678 bp PCR fragment from the P53 cDNA from 481–1159 into the BamH I/Xba I site in RF M13mp18. That region spans exons 5–9 of the P53 cDNA. The identity of the insert was verified by DNA sequencing. Bovine pancreatic DNase I grade II (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and RNase A (Sigma Biochemicals, St. Louis, MO) were used as suggested by the manufacturers. Lysozyme was obtained from Sigma Biochemicals. All molecular biological or biochemical methods not explicitly described were performed using standard protocols [81].

Table 1.

ODNs used in this study. All ODNs shown are 5’→3’ in polarity.

| ODN | Sequence | Use* |

|---|---|---|

| CMH3 | AGCTCTCGGATCCTCTCGAA** | Extension Assay |

| CMH5 | ATGAGCGCTGCTCAGATAG | Assay |

| CMH6 | GGTGGTACAGTCAGAGCCAAC | Linear/Assay |

| CMH7 | GTGACGAAACTCAGTGTTAC | Assay |

| CMH8 | TCGAGAGGGTTGATATAAG | Linear/Assay |

| LIGFor | GCCGCCATGGTTCTTAAAATTCTGAAC | Nco I |

| LIGRev | GCGCGGATCCCATAGACCAGTTACCTCA | BamH I |

| OGG1 siRNA 214 |

GAGGUGGCUCAGAAAUUCCtt | sense |

| GGAAUUUCUGAGCCACCUCtt | antisense | |

| OGG1 siRNA 330 |

GCUUGAUGAUGUCACCUACtt | sense |

| GUAGGUGACAUCAUCAAGCtg | antisense | |

| OGG1 siRNA 366 |

GCUAGAUGUUACCCUGGCUtt | sense |

| AGCCAGGGUAACAUCUAGCtg | antisense | |

| Non specific siRNA Control |

ttAUGUUGACGUGUUCCAAAU | sense |

| ttAUUUGGAACACGUCAACAU | antisense | |

| 8-oxoG | pTGGTGGTGCCCTAT8GAGCCGCCTGA | DNA synthesis |

| OGG1 RT-PCR |

CGTGGACTCCCACTTCCAAGAG | forward |

| ATGGTAGGTGACATCATCAAGCT | reverse | |

| GAPDH RT-PCR Control |

CCAAGGTCATCCATGACAAC | forward |

| CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCA | reverse |

Assay—use for exponential amplification, antisense—si RNA for the antisense strand, BamH I—inserts a Bam HI site on the 3’ end of the T4 DNA Ligase gene, DNA synthesis—to insert a modified base, Extension Assay—primer extension to show position of 8-oxoG, forward—primer for RT-PCR, Linear—primer for extension in the first step of the assay, Ncol—inserts a Nco I site on the 3’ end of the T4 DNA Ligase gene, reverse—primer for RT-PCR

The underlined sequences represent two mutations found in the sequenced exons 5–9 for the ODN that was used for primer extension analysis located at positioni 166–1147 in the NCBI database—AF307851 (nucleotide).

Cell culture

Mammalian cell line AD293, a transformed human kidney cell line, was obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA) and was grown in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were regularly passaged to maintain exponential growth. Synthetic siRNA was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Isolation of T4 DNA ligase coding sequence and purification of T4 DNA ligase

E. coli phage T4 was obtained from the ATCC and phage DNA was purified by phenol/CHCl3 extraction. A PCR fragment of full-length cDNA of T4 DNA ligase was prepared with Pfu DNA polymerase and primers (Table 1). The restriction endonuclease cleaved PCR products were subcloned into the Nco I and BamH I sites of a pET-28a(+)-modified plasmid with a tobacco etch virus protease site in the synthesized protein with a His6 tag at the C-terminal end (Novagen, Madison, WI and Yuan Chen, City of Hope). Standard expression and purification methods were used to prepare the T4 DNA ligase. Protein purity was monitored by SDS–PAGE. The activity of T4 DNA ligase was compared to commercial preparations using an assay ligating Hind III fragments of λ DNA at different dilutions and separating products on agarose gels.

In vitro synthesis of RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG

A double-stranded, closed circular molecule with a unique 8-oxoG adduct was formed using in vitro DNA synthesis and ligation. Briefly, for DNA synthesis, 15pmol (130ng) of the kinased 8-oxoG ODN (Table I) was annealed to the single-stranded M13mp18-P53 (7µg) by heating to 80°C and cooling to 30°C slowly over 30 min. Synthesis and ligation were conducted on the annealed product using the RB69 DNA polymerase (1.4 µg), and T4 DNA ligase (400U) in the presence of 2.5mM ATP and 150µM each dNTP. The reaction mixture was incubated using the following temperatures and times: 4°C for 5min, 22°C for five min, and 30°C for three hours. The closed circular plasmid was purified using a CsCl gradient (1g/ml) in 0.4 mg/ml ethidium bromide, followed by extraction with water-saturated butanol, dialysed against 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA for 6h, ethanol precipitated for 16h at 4°C, centrifuged, washed with 70% ethanol and re-suspended in 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA at a concentration of 1mg/ml. In order to synthesize sufficient RF DNA, either a number of reactions or large scale reactions were performed and the DNA was pooled prior to CsCl gradient purification of supercoiled DNA.

Characterization of 8-oxoG cccDNA

After making 8-oxoG RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG, we confirmed that over 90% of the DNA was a covalently-closed circle with a single 8-oxoG in the region for analysis using primer extension. After treatment with Fpg, the RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG DNA was purified by phenol/CHCl3 extraction and ethanol precipitation. The extension reaction used 1X Pfu buffer (Stratagene), 200 µM of each dNTP, 20 µM single primer CHM3 (5’32P-end labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase) (Table 1) and Pfu polymerase in 100 µl total reaction volume at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 40s, 53°C for 40s, 72°C for 1min, 72°C for 10min extension. Products of the primer extension reaction were separated on a DNA sequencing gel and imaged using a Typhoon 9410 phosphorimager system (GE Health Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

siRNA knock-down of OGG1 expression in AD293 cells

Briefly, 24h before transfection, AD293 cells were plated on 100cm plates at 80%-90% confluence. For transfection, 50µl Lipofectamine 2000 diluted in 1.5ml Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) was incubated for 5min at room temperature. At 5min, per plate, 520 pmole of double-stranded siRNA in 1.5ml of Opti-MEM was mixed with the Lipofectamine 2000/Opti-MEM mixture for each plate, and then applied to the cells. At 6h post-transfection, each plate was supplemented with 7ml of DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum. Initial experiments verified the knock down 48h post transfection was almost 100%. At 48h another transfection of AD293 cells was conducted and the knock down verified at 96h following the first transfection. The knock-down of production of OGG1 was verified using Western blotting of OGG1. As a controls, OGG1 expression in AD293 cells was compared to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and OGG1 production was compared to that of tubulin.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gene expression was analyzed using RT-PCR. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2µg of total RNA using SuperScript reverse transcriptase II (Invitrogen). For OGG1 expression primers were added (Table 1), and the amplification was carried out at 94°C for 40s, 54°C for 40s, and 72°C for 1min for 26 cycles [81]. For analyzing GAPDH gene expression, primers (Table 1), and the reactions were performed at 94°C for 40s, 53°C for 40s, and 72°C for 1min for 23 cycles.

In vivo assay for 8-oxoG repair

Liposome transfection in AD293 cells

4µg of covalently, closed-circular (ccc)-RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG was transfected into 1×106 AD293 cells on a 100mm plate (60% confluence) using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were then incubated for 3h to 48h and harvested.

Nucleofection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, MO) density gradient centrifugation (specific gravity 1.077) for 30min at 400g. Nucleofection was performed using a Nucleofector device (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) and the human T-cell nucleofector kit (Cat. # VPA-1002) following procedures recommended by the manufacturer. Cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 5×106 PBMCs per nucleofection reaction were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, centrifuged and resuspended in 100µl of the nucleofector solution and 2µg of the plasmid DNA being tested. Approximately, 1ml of whole blood produced 1×106 PBMCs, therefore 5ml of whole blood produced the quantity of cells needed for transfection. Cells were then transferred into a nucleofection cuvette, which was inserted into the Nucleofector and pulsed using nucleofector program (Program U-14). Cells were then immediately transferred into pre-warmed 500µl RPMI and kept at 37°C for 15 min. Subsequently cells were transferred to culture dishes containing pre-warmed IMDM with 20% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37°C for 2, 4, 6, 16, and 24h post nucleofection as discussed in the results. Studies using the pmaxGFP plasmid expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) demonstrated that this procedure resulted in transfection of 22.0±4.3% of cells based on flow cytometry analysis performed 24 hours after nucleofection.

DNA repair assay using siRNA knock down of OGG1

For siRNA knock down experiments of OGG1 and the plasmid assay, a transfection of the OGG1-siRNA 214 (Table 1) was performed as described above. The only difference is that at 2d post-transfection, the second transfection of OGG1-siRNA 214 was performed, but 4µg of RF M13mp18-p53-8-oxoG was added to the Opt-MEM along with the OGG1-siRNA 214 for transfection. Cells were incubated as a function of time, harvested, and DNA extracted to monitor in vivo repair as for the cells without siRNA treatment.

DNA isolation

Any contaminating extracellular DNA was eliminated by treatment of cell cultures with DNase I (40µl of phosphate-buffered saline solution) before DNA isolation and following thorough washing of the cells, nuclei were isolated [82]. Briefly, 1×106 cells were lysed by addition of 2ml of the following buffer: 0.3M sucrose, 60mM KCl, 15mM NaCl, 60mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.5mM spermidine, 0.15mM spermine, 2mM EDTA and 0.5% Ipegal. The cells with the buffer are incubated on ice for 5 min, followed by centrifugation for 5min at 1000g and 4°C to pellet the nuclei. Nuclei are washed once with the buffer without Ipegal and extrachromosomal RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG DNA was recovered from nuclei by a small-scale alkaline lysis method [83]

Fpg treatment of episomal DNA

Recovered RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG DNA (25ng) was treated with E. coli Fpg protein (400ng) in a buffer of 100mM KCl, 70mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.5, 0.5mM EDTA for 1h at 37°C to remove any remaining 8-oxoG and introduce a break in the unrepaired closed circular DNA. These conditions result in cleavage of all the 8-oxoG in the RF DNA. Complete cleavage of the 8-oxoG containing DNA is necessary for the assay success, otherwise residual 8-oxoG could allow some products to form that would falsely indicate repair. The technique used for DNA isolation has been shown to allow the Fpg to function without inhibition and the quantity of Fpg yields 100% cleavage based on isolation of plasmids with known amounts of 8-oxoG.

Determination of episomal DNA concentration

We determined the concentrations of RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG isolated using a standard sample concentration program in the DNA Engine Opticon™ (BioRad-MJ Research, Waltham, MA). An unknown DNA sample from the isolation of the extrachromosomal DNA is diluted from 1- to 10-fold for template and standard samples are 2µg, 1µg, 0.5 µg, 0.1µg, 0.05µg, 0.01µg. Standard PCR is carried out in 25µl reactions and analyzed in triplicate. Briefly, 10X Pfu buffer (200mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 20mM MgSO4, 10mM KCl, 100mM (NH4)2 SO4, 1% Triton X-100), 200µg/ml BSA (New England Biolabs), 10% DMSO, 200µM dNTP, 400µM internal control primer set (CMH7 and CMH8, Table 1), 1U Pfu polymerase, 1.3µl of SYBR Green (diluted 1 to 1000 in TE, pH 8.0, Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) and diluted template. Except for the different templates, mixtures of the remaining agents were made and were distributed to Eppendorf tubes on ice; then added to the template samples. PCR mixtures were distributed to hard-shell thin-walled skirted microplates (MJ Research) at room temperature and covered with Microseal “B” Adhesive Film (MJ Research). Conditions of standard PCR were as follows: 94°C for 3min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 40s, 53°C for 40s, 72°C for 1min, and 82°C 2s for plate reading (for fluorescence detection). After completion of the PCR is done, DNA Engine Opticon™ data is used to determine the concentration of the unknown samples.

Linear PCR amplification

The first step is a linear PCR amplification where DNA synthesis is arrested if there is a DNA break. The extended DNA is then subject to real-time PCR amplification. Once the amount of DNA is determined using the standard curve, linear extension was performed on 20pg of template DNA with 20pmol (175ng) CMH6 ODN (Table 1) that uses the strand containing the adduct or the break as the template in 50µl total volume. Conditions for linear PCR were 94°C for 3min, followed by 15 cycles of 94°C for 40s, 53°C for 40s, 72°C for 1min, followed by incubation at 72°C for 10min. A linear amplification of the M13mp18 internal control region was performed using the CMH8 ODN with identical conditions to those for the CMH6 linear amplification reaction.

Exponential real-time PCR amplification

To determine the repair rate in cells, exponential real-time PCR was carried out using aliquots from the primer extension reactions. From the linear amplification reactions, 1µl was removed and 20pmol CMH5 and CHM6 primers (Table 1) were added (full length product 158bp). Other reagents used were the same as those for standard PCR in a total volume of 25µl. The reaction conditions are: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 40s, 53°C for 40s, 72°C for 1min, with the plates read using fluorescence detection. A parallel control real-time PCR reaction for the control DNA region using the CMH7 and CMH8 primers (full length product 178bp) (Table 1) with 1µl of the linear amplification reaction was also performed. Real-time PCR was carried out using a DNA Engine Opticon™ (MJ Research). After PCR, data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. Repair rates were analyzed using a ratio of damage region/control region to calculate percent repair.

In vitro mixing experiment

A mixing curve was used to demonstrate the assay linearity. Using RF M13mp18-p53 DNA (100% Repair, closed circular) and nicked RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG (100% nicked by Fpg) DNA, the RF M13mp18-P53-9:nicked DNA ratio was varied from 0 to 1 using a total of 400pg of DNA for each amplification. The mixtures were subjected to analysis using the DNA repair assay described above.

Western blotting

Cells were washed with PBS and collected by scraping. Lysis was performed in ice-cold homogenization buffer (1XPBS, 1% Ipegal CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS). After incubation on dry ice for 10 min, the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10min. After repetition three times, the homogenization mixture was centrifuged at 15,000g for 15min. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the Bradford procedure (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The proteins (50 µg of the whole cell extract) were resolved on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with rabbit polyclonal IgG against OGG1 at a 1 to 3000 dilution, and then with horseradish peroxidase-labeled antibodies against rabbit IgG (Amersham Biosciences) at a 1 to 3000 dilution and the signals were observed with enhanced chemi-illuminescence (Amersham Biosciences). To compare the amounts of protein present in the Western assay, blots were re-probed with an anti-β-tubulin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; sc-5274).

Results

Synthesis and characterization of RF M13mp18-P53 DNA with a unique 8-oxoG at a defined position

The method of construction of a ccc double-stranded (ds) DNA containing a unique 8-oxoG at a defined site is based on a site-directed mutagenesis procedure using ssDNA as a template. In order to achieve higher yields of these types of constructs, we first purified ss M13mp18-P53 DNA and annealed a phorphorylated ODN with a single 8-oxoG (Figure 1). The 3’-terminus of the oligdeoxyribonucleotide acts as primer for complementary strand synthesis by RB69 polymerase. The newly synthesized DNA strand is covalently closed with T4 DNA ligase producing a circular DNA containing 8-oxoG with a yield of cccDNA is ~50%. CsCl/EtBr gradient purification yields a product with greater than 90% purity of the DNA substrate in the (ccc) form.

Figure 1. Damage and vectors used in this study.

(a) 8-oxoguanine, (b) M13mp18-P53 with the cDNA from exons 5–9 of human P53, (c) P53 coding sequence from the NCBI database—AF307851 (nucleotide) used in these experiments. The gray arrows and sequences indicate the ODNs, the bold black sequence the ODN for the 8-oxoG, and the actual position highlighted in gray with a gray asterisk.

To confirm that the purified, ccc-M13mp18-P53 DNA contains a single 8-oxoG site, it was incubated with Fpg to introduce a specific nick by the DNA glycosylase/AP lyase activity. Following treatment with Fpg, a 5’ primer extension reaction using a 32P labeled primer demonstrates that the 8-oxoG is in the correct position (Figure 2). This contrasts with the unmodified DNA in the control reaction which showed only a very weak band following Fpg treatment and primer extension. No damage that blocks primer extension is observed in the region used for amplification in these experiments.

Figure 2. Primer extension assay for vectors with unique modified sites.

Primer extension was carried out using CHM3 (Table 1) for both the undamaged DNA (Control/Fpg) and the damaged DNA (8-oxoG/Fpg) when both the control and 8-oxoG containing RF M13mp18-P53 DNAs have been treated using Fpg. Reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods.

Assay linearity

The assay design is outlined in Figure 3. We hypothesized that damage to recovered cccDNA would result in a reduction of the available template for PCR (decreased DNA integrity) in the damaged P53 cDNA region. The 8-oxoG is removed from the RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG DNA using Fpg. Following the 8-oxoG removal and nick in the cccDNA, a linear PCR extension is performed using the strand which originally contained the 8-oxoG. The products of the linear extension include repaired DNA that should extend beyond the original position of the 8-oxoG and unrepaired DNA that does not support extension beyond the 8-oxoG position. The use of an aliquot of the primer extension reaction should then yield differences between the repaired and unrepaired DNA. In quantitative real time PCR, the presence of the 8-oxoG is reflected by an increase in the number of cycles to observe an amplification signal. The control region, part of M13mp18 gene, was unaffected by Fpg treatment. The repair rates of cccDNA damage were analyzed by calculating the number of cycles for the damaged region (P53 region) divided by the number of cycles of the internal control region (mp13region). The (cycles for the undamaged P53 region)/(cycles for the M13 Region) ratio was defined as 100%, and cccDNA damage would be expressed as a percentage of this control value. The 0% repair value was set by the (cycles for the damaged P53 region)/(cycles for the M13 Region) ratio. A signal is still obtained from 0% repaired DNA due to the fact that the 1/50 dilution used in the exponential PCR still has the undamaged complementary strand present. Thus, given enough amplification, the fluorescence observed is significant (Figures 4a and 5a). However, to use this assay for the study of in vivo repair, the assay must be linear. Therefore, we removed the unique 8-oxoG from RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG DNA using Fpg and performed a mixing experiment with undamaged RF M13mp18-P53 DNA (Figure 4, Table 2). The linear response of triplicate samples in the mixing experiment demonstrates that the assay can be utilized in repair experiments (Figure 4, Table 2).

Figure 3. Outline of method to monitor in vivo repair of 8-oxoG in RF M13mp18-P53.

The left side of the figure represents the P53 coding sequence with the 8-oxoG damage and the right side of the figure the control M13 region. Following harvest of episomal DNA, the concentration of DNA obtained is determined using real time PCR with a non-transfected, undamaged M13 control sequence with no damage using a standard curve by amplification of the control region of the M13mp18-P53 (This is not depicted in the figure). The M13mp18-P53 is then reacted with Fpg to remove any remaining 8-oxoG (black circle) and nick the DNA (black arc). A linear PCR extension (15 cycles) with a single ODN is performed using the original damage-containing strand as a template with CHM6 and CHM8 ODN primers. At the end of the extension reaction, a 1µl aliquot of the product is removed from both reactions, new CHM5 and CHM6 primers are added and to the other tube new CHM7and CHM8 primers and the DNA products of the linear extension reactions (linear amplification) are amplified using exponential real-time PCR in the presence of Sybr Green.

Figure 4. Linearity of the assay as determined using cleaved and undamaged M13mp18-P53.

(a) Log fluorescence versus cycle number obtained by real time PCR for the repair of 8-oxoG in nicked M13mp18-P53 DNA in AD293 cells in the region of the adduct. The M13mp18-P53 was nicked using Fpg and mixed with M13mp18-P53 without an 8-oxoG. The numbers correspond to the points in c. (b) Log fluorescence versus cycle number obtained by real time PCR of the M13mp18-P53 DNA control region. The colors correspond to the same mix as for the P53 region. The differences in the scans are too close to indicate on the figure. (c) Plot of the mixing curve from 0–100% OGG1 (nicked M13mp18-P53). Each point is the mean of triplicate assays, and the standard deviation from the mean for triplicate assays is indicated on the figure. The calculations for the data are presented in Table 2. The correlation coefficient value indicating linearity is 0.987.

Figure 5. siRNA knock-down of OGG1 mRNA in AD293 cells.

(a) RT-PCR using 3 different target siRNAs. M corresponds to markers, AD293 corresponds to OGG1 mRNA amplified from those cells, and the siRNAs correspond to the different ODNs in the text. The GAPDH amplification is given for the cells as a control. (b) Western blot showing the reduction of OGG1 at 48h and 96h compared to the production of tubulin. The AD293 cells are without siRNAs, the AD293 cells transfected with the different siRNAs, and the AD293 cells with the nonspecific siRNAs are also indicated.

Table 2.

Calculations from real time-PCR data for mixing of damaged and undamaged RF M13mp18-P53 DNA.

| % 8-oxoG | CP531 | CM132 | Avg CP533 | σP534 | Avg. CM135 | σM136 | Avg. CM13/Avg. CP537 | σRatio8 | Repair (%)9 | σRepair10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 26.248 25.661 25.648 |

9.808 9.324 9.669 |

25.852 | 0.343 | 9.600 | 0.249 | 0.371 | 0.0108 | 0.0 | 6.4 |

| 10.0 | 24.357 24.529 24.227 |

9.397 9.443 9.607 |

24.371 | 0.151 | 9.483 | 0.110 | 0.389 | 0.0051 | 10.5 | 3.0 |

| 30.0 | 23.463 22.319 23.811 |

9.536 9.235 9.164 |

23.198 | 0.781 | 9.311 | 0.197 | 0.401 | 0.0159 | 17.7 | 9.4 |

| 50.0 | 22.145 22.469 22.306 |

9.689 9.452 9.886 |

22.306 | 0.162 | 9.675 | 0.217 | 0.434 | 0.0102 | 36.8 | 6.0 |

| 70.0 | 19.566 18.562 18.871 |

9.292 9.250 9.206 |

19.000 | 0.515 | 9.249 | 0.043 | 0.487 | 0.0133 | 68.1 | 7.9 |

| 90.0 | 18.327 17.617 17.858 |

9.082 8.764 9.118 |

17.934 | 0.361 | 8.988 | 0.194 | 0.501 | 0.0148 | 76.5 | 8.7 |

| 100.0 | 16.838 16.595 16.917 |

9.170 9.184 8.884 |

16.783 | 0.168 | 9.080 | 0.169 | 0.541 | 0.0114 | 100.0 | 6.7 |

Number of cycles for amplification of the P53 region,

Number of cycles for amplification of the M13 region,

Average number of cycles for amplification of the P53 region,

Standard deviation of cycles for amplification of the P53 region,

Average number of cycles for amplification of the M13 region,

Standard deviation of cycles for amplification of the M13 region,

Ratio of the average cycles for amplification of the M13 region divided by the average cycles for amplification of the P53 region,

Standard deviation for the average cycles for amplification of the M13 region divided by the average cycles for amplification of the P53 region (value in 7 multiplied by the square root of σCm132/Cm132 + σCP532/CP532, where the Cs are the average values for the amplification of each region),

Repair calculated as 100(Avg. CM13/Avg. CP53 − Minimum Avg, CM13/CP53)/(Maximum Avg. CM13/Avg. CP53 − Minimum Avg. CM13/Avg. CP53), σRepair calculated by placing the standard deviation of the ratios into the equation in 9 and taking the difference.

Knockdown of OGG1 expression

The assay method should distinguish between cells that are proficient or deficient in OGG1 expression. OGG1 is a DNA glycosylase important in the elimination of 8-oxoG adducts. To test that, we prepared a cell line that was deficient in OGG1 excision of 8-oxoG using siRNA. Figure 5 shows that there is a significant reduction in both OGG1 mRNA levels and in the protein produced for in AD293 cells at 2 d post transfection. The reduction of OGG1 activity is maintained following a second treatment with siRNA 214 at 48 h. Based on these data, the siRNA should decrease the levels in AD293 cells enough to manifest a phenotype with respect to repair of 8-oxoG. One of the 3 21 bp oligoribonucleotides, siRNA 214, is the most efficient at the reduction of OGG1 levels (Figure 5).

Repair of 8-oxoG in episomal DNA in cells proficient and defective in 8-oxoG repair

To assess the repair of 8-oxoG in vivo, the RF M13mp18-P53 DNA-8-oxoG was transfected into AD293 cells and cells were harvested from 2h to 48h post transfection. From the purified nuclei, the episomal DNA was isolated and subjected to the assay in triplicate. In comparison to this mixing experiment, for repair samples, it is necessary to perform the assay on an undamaged template to obtain the value for 100% repair.

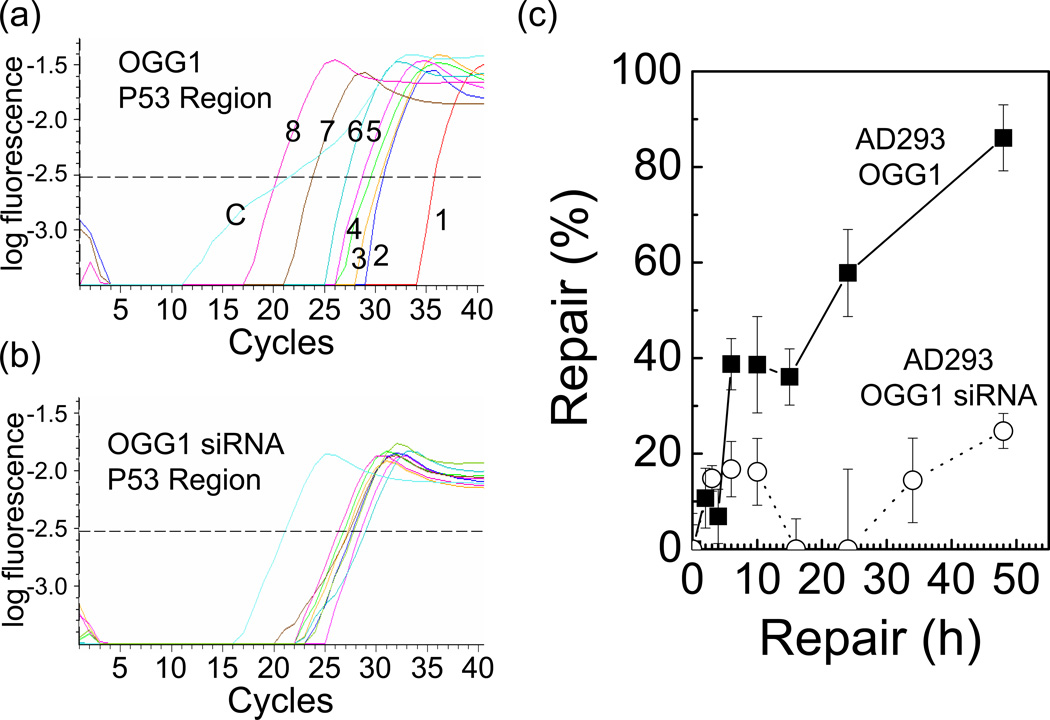

Calculations used to monitor 8-oxoG repair are described for the data set for transfection of the RF M13mp18-P53 DNA-8-oxoG into AD193 cells (Table 2). This quantitative PCR assay reveals that in AD293 cells, 8-oxoG is not efficiently removed, even 24h after incubation, only 50%, but at 48h, over 80% repair is observed (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Repair of 8-oxoG following transfection into a human cell line.

The concentration of cccDNA was determined using real time PCR comparison to a standard curve. Harvested DNA was treated with Fpg to introduce a nick in all unrepaired DNA. (a) Real-time PCR results for the repair of 8-oxoG in M13mp18-P53 DNA in AD293 cells in the region of the adduct. The numbers correspond to the following times: 1–0 h (100% damaged), 2–2h, 3–4h, 4–6h, 5–10h, 6–15h, 7–24h, 8–48h. The curve is fitted to a sigmodal function. ‘C’ represents the control undamaged DNA that corresponds to 100% repair. The dotted line represents the points in each of the curves at which the cycle number was obtained. (b) Real-time PCR results for repair of the M13mp18-P53 DNA in AD293 cells with the OGG1 siRNA knockdown. The dotted line represents the points in each of the curves at which the cycle number was obtained. (c) Repair determined using real time PCR. Plots of the percent repair as a function of time are indicated. Repair of 8-oxoG in AD293 cells is represented by closed squares and repair in AD293 cells with siRNA knock down of OGG1 is represented by open circles. Each point is the mean of triplicate assays, and the standard deviation from the mean for triplicate assays is indicated on the figure.

We reduced cellular levels of OGG1 for 2d using the siRNA 214 and then transfected the RF M13mp18-p53 DNA-8-oxoG along with more siRNA 214. Although the AD293 cells repair virtually all the 8-oxoG in 48h, there is less than 30% repair observed in the cells that were subjected to siRNA knock own of OGG1 expression (Figure 6). This indicates that the assay is sensitive to differences in repair of 8-oxoG in cells. There is some change in the repair levels that could be due to variable OGG1 transcript levels (Figure 5b, OGG1 4d), but overall the OGG1 levels remain low during the experiment.

In other experiments, we have performed the assay on AD293 cells that were thawed at a different time, grown, transfected with the RF M13mp18-P53 DNA-8-oxoG, harvested the cccDNA, and then performed the assay. Under the same conditions, at least for AD293, there was almost no difference in the observed repair rates. This demonstrated that the technique is robust and repeatable.

Repair of 8-oxoG normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells

To monitor repair in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, we obtained blood samples from 3 volunteers. The method and strategy are the same as for the AD293 cells. The major difference is that the transfection method uses nucleofection, a modified electroporation technique. Using this method it is possible to transfect the peripheral blood mononuclear cells at ~40% efficiency. The 3 individuals were transfected with the RF M13mp18-P53-8-oxoG DNA and harvested at different times. Therefore, we can monitor the repair in normal human cells. For 2 individuals only single blood samples were analyzed, but for a third individual, 2 samples were obtained and show that the half-life for 8-oxoG is similar. For these individuals, the half-life for 8-oxoG repair varies from 2–4h. At present, the sampling is too small to yield a range of values for normal individuals, but from these limited experiments, 8-oxoG repair is rapid, with half-lives of under 5 hours. One significant point in this report is the capacity to screen for DNA repair defects in individual samples without resorting to stimulation.

Discussion

In this report, we have detailed a method to monitor DNA repair in mammalian cells and yeast using a simple transfection and quantitative real time PCR. The method does not require the isolation of large amounts of DNA and is reproducible. Compared to the assays previously used to monitor DNA repair in mammalian cells, this one requires less manipulation and also provides for triplicate samples [37]. The use of an internal control sequence means that it is not necessary to perform co-transfections or to estimate the transfection efficiency.

The method has a linear response over a range necessary to monitor repair differences in human cells. When used to monitor 8-oxoG repair, the rate was at least 2-fold slower in AD293 cells than that reported in immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblast cells [37] and also slower than repair monitored in the normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (this study). The AD293 cell line is also deficient in MLH1, so there may be a contribution of mismatch repair to the elimination of 8-oxoG. Previous studies have also shown a role for NER in 8-oxoG elimination [39]. Therefore, the elimination of oxidative damage could be linked to base, nucleotide, and mismatch repair. In the future, this technique could be employed to evaluate the roles of these three repair systems in protection against 8-oxoG.

This technique has some similarity to other techniques that involve PCR based assays, but those techniques all introduced a number of sites into either plasmids or genomic DNA. The use of an episome with a unique damage site permits the use of other sequences in the episome as an internal standard. This increases the accuracy of the assay and renders it almost independent of transfection. Previous work using host cell reactivation assays with either luciferase or chloramphenicol acetyltransferase assays has not used this type of internal control sequence. Moreover, this assay directly monitors repair of the adduct in DNA, unlike the host cell reactivation assays that depend on the synthesis of a functional protein.

Since this method depends on the amplification of a single strand of DNA, we should be able to adapt this method to study transcription effects. DNA repair linked to transcription is difficult to examine using DNA randomly damaged at multiple sites in episomes. With this assay, it is possible to investigate damage on either transcribed or non-transcribed strands. This can be critical in some experiments, for example repair of 8-oxoG by OGG1 has been linked to repair primarily on the non-transcribed strand and that would not be observable using conditions for most host cell reactivation assays [37].

Despite the advantage of the assay, the preparation of the substrate is more difficult than host cell reactivation assays. The requirement to have a unique damaged site means that preparation of the episome is more challenging than in most host cell reactivation experiments that are based on the observation of protein activity by damaging an episome globally. The synthesis of large amounts of modified DNAs is necessary, but the use of both the DNA polymerase and DNA ligase synthesized in the laboratory facilitates this task. To obtain the quantities of modified DNA, we often perform a number of reactions in parallel to insure that there will be enough cccDNA to use. Even with this hurdle, the fact that the episomal DNA has its own internal standard in this assay provides a distinct advantage and yield data on the repair capacity in cells that does not depend on preparing cell extracts [22; 55].

Host cell reactivation assays have also been used to investigate peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Those are sensitive, but lack the specificity to examine the repair kinetics of the adducts induced, since a property of a synthesized protein is usually detected. The sensitivity of this assay, the possibility to easily obtain data, and its reproducibility coupled with the use of an efficient means to transfect lymphocytes makes this an ideal system for the investigation of DNA repair in patient samples. With several modifications, it should also be adaptable to multiplexing. This method will prove useful in studies of populations that have potential DNA repair defects and should be adaptable to many types of DNA damage.

Figure 7. Repair of 8-oxoG following transfection into human white blood cells.

cccDNA harvested as a function of time following transfection into human PBMCs is treated as in Figure 6. The numbers represent individual samples. Each transfection used 1×106 PBMCs. Plots represent the percent repair as a function of time for each of the different patient samples. Each point is the mean of triplicate assays, and the standard deviation from the mean for triplicate assays is indicated on the figure. P1, P2, and P3 refer to the individuals assayed. P1 was assayed twice on different days.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. William Konigsberg for the RB69 overproducing clone and Ms. Xiangrong Zhao for preparation of the RB69 DNA polymerase protein and Mr. Stephen Bates for assistance with cell culture. This investigation was funded by the City of Hope, a SPORE Grant (Dr. Stephen Forman), and the National Cancer Institute (TRO, RB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Hyun-Wook Lee, Biology Department, Hematology Department, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1450 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010.

Hae-Jung Lee, Biology Department, Hematology Department, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1450 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010.

Chong-mu Hong, Biology Department, Hematology Department, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1450 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010.

David J. Baker, Biology Department, Hematology Department, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1450 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010

Ravi Bhatia, Department of Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1450 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010.

Timothy R. O’Connor, Biology Department, Hematology Department, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1450 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010

References

- 1.Barnes DE, Lindahl T. Repair and genetic consequences of endogenous DNA base damage in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:445–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins AR. Assays for oxidative stress and antioxidant status: applications to research into the biological effectiveness of polyphenols. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:261S–267S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.261S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bont R, van Larebeke N. Endogenous DNA damage in humans: a review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:169–185. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedberg EC, McDaniel LD, Schultz RA. The role of endogenous and exogenous DNA damage and mutagenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishimura S. Involvement of mammalian OGG1(MMH) in excision of the 8-hydroxyguanine residue in DNA. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:813–821. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00778-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Termini J. Hydroperoxide-induced DNA damage and mutations. Mutat Res. 2000;450:107–124. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wogan GN, Hecht SS, Felton JS, Conney AH, Loeb LA. Environmental and chemical carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekiguchi M, Tsuzuki T. Oxidative nucleotide damage: consequences and prevention. Oncogene. 2002;21:8895–8904. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider JE, Price S, Maidt L, Gutteridge JM, Floyd RA. Methylene blue plus light mediates 8-hydroxy 2'-deoxyguanosine formation in DNA preferentially over strand breakage. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:631–635. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.3.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider JE, Jr, Phillips JR, Pye Q, Maidt ML, Price S, Floyd RA. Methylene blue and rose bengal photoinactivation of RNA bacteriophages: comparative studies of 8-oxoguanine formation in isolated RNA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;301:91–97. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood ML, Esteve A, Morningstar ML, Kuziemko GM, Essigmann JM. Genetic effects of oxidative DNA damage: comparative mutagenesis of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6023–6032. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.22.6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamiya H, Murata-Kamiya N, Koizume S, Inoue H, Nishimura S, Ohtsuka E. 8-Hydroxyguanine (7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine) in hot spots of the c-Ha-ras gene: effects of sequence contexts on mutation spectra. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:883–889. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas D, Scot AD, Barbey R, Padula M, Boiteux S. Inactivation of OGG1 increases the incidence of G. C-->T. A transversions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: evidence for endogenous oxidative damage to DNA in eukaryotic cells. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s004380050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichinose T, Nobuyuki S, Takano H, Abe M, Sadakane K, Yanagisawa R, Ochi H, Fujioka K, Lee KG, Shibamoto T. Liver carcinogenesis and formation of 8-hydroxy-deoxyguanosine in C3H/HeN mice by oxidized dietary oils containing carcinogenic dicarbonyl compounds. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004;42:1795–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russo MT, De Luca G, Degan P, Parlanti E, Dogliotti E, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, Yang H, Miller JH, Bignami M. Accumulation of the oxidative base lesion 8-hydroxyguanine in DNA of tumor-prone mice defective in both the Myh and Ogg1 DNA glycosylases. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4411–4414. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Y, Yang H, Cunanan C, Okamoto K, Shibata D, Pan J, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, McIlhatton M, Fishel R, Miller JH. Deficiencies in mouse Myh and Ogg1 result in tumor predisposition and G to T mutations in codon 12 of the K-ras oncogene in lung tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3096–3102. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakabeppu Y, Tsuchimoto D, Ichinoe A, Ohno M, Ide Y, Hirano S, Yoshimura D, Tominaga Y, Furuichi M, Sakumi K. Biological significance of the defense mechanisms against oxidative damage in nucleic acids caused by reactive oxygen species: from mitochondria to nuclei. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1011:101–111. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-41088-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arai T, Kelly VP, Komoro K, Minowa O, Noda T, Nishimura S. Cell proliferation in liver of Mmh/Ogg1-deficient mice enhances mutation frequency because of the presence of 8-hydroxyguanine in DNA. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4287–4292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakumi K, Tominaga Y, Furuichi M, Xu P, Tsuzuki T, Sekiguchi M, Nakabeppu Y. Ogg1 knockout-associated lung tumorigenesis and its suppression by Mth1 gene disruption. Cancer Res. 2003;63:902–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P, Birincioglu M, Rodriguez H. Free radical-induced damage to DNA: mechanisms and measurement. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:1102–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gackowski D, Speina E, Zielinska M, Kowalewski J, Rozalski R, Siomek A, Paciorek T, Tudek B, Olinski R. Products of oxidative DNA damage and repair as possible biomarkers of susceptibility to lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4899–4902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paz-Elizur T, Krupsky M, Blumenstein S, Elinger D, Schechtman E, Livneh Z. DNA repair activity for oxidative damage and risk of lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1312–1319. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scharer OD. Chemistry and biology of DNA repair. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:2946–2974. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu R, Nash HM, Verdine GL. A mammalian DNA repair enzyme that excises oxidatively damaged guanines maps to a locus frequently lost in lung cancer. Curr Biol. 1997;7:397–407. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roldan-Arjona T, Wei YF, Carter KC, Klungland A, Anselmino C, Wang RP, Augustus M, Lindahl T. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a human cDNA encoding the antimutator enzyme 8-hydroxyguanine-DNA glycosylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8016–8020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radicella JP, Dherin C, Desmaze C, Fox MS, Boiteux S. Cloning and characterization of hOGG1, a human homolog of the OGG1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8010–8015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenquist TA, Zharkov DO, Grollman AP. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7429–7434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazra TK, Izumi T, Boldogh I, Imhoff B, Kow YW, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Mitra S. Identification and characterization of a human DNA glycosylase for repair of modified bases in oxidatively damaged DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3523–3528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062053799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osterod M, Larsen E, Le Page F, Hengstler JG, Van Der Horst GT, Boiteux S, Klungland A, Epe B. A global DNA repair mechanism involving the Cockayne syndrome B (CSB) gene product can prevent the in vivo accumulation of endogenous oxidative DNA base damage. Oncogene. 2002;21:8232–8239. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fromme JC, Bruner SD, Yang W, Karplus M, Verdine GL. Product-assisted catalysis in base-excision DNA repair. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:204–211. doi: 10.1038/nsb902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dianov G, Bischoff C, Piotrowski J, Bohr VA. Repair pathways for processing of 8-oxoguanine in DNA by mammalian cell extracts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33811–33816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hazra TK, Izumi T, Maidt L, Floyd RA, Mitra S. The presence of two distinct 8-oxoguanine repair enzymes in human cells: their potential complementary roles in preventing mutation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5116–5122. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosenquist TA, Zaika E, Fernandes AS, Zharkov DO, Miller H, Grollman AP. The novel DNA glycosylase, NEIL1, protects mammalian cells from radiation-mediated cell death. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:581–591. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue M, Shen GP, Chaudhry MA, Galick H, Blaisdell JO, Wallace SS. Expression of the oxidative base excision repair enzymes is not induced in TK6 human lymphoblastoid cells after low doses of ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2004;161:409–417. doi: 10.1667/3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang QM, Yonekura S, Takao M, Yasui A, Sugiyama H, Yonei S. DNA glycosylase activities for thymine residues oxidized in the methyl group are functions of the hNEIL1 and hNTH1 enzymes in human cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Page F, Klungland A, Barnes DE, Sarasin A, Boiteux S. Transcription coupled repair of 8-oxoguanine in murine cells: the ogg1 protein is required for repair in nontranscribed sequences but not in transcribed sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8397–8402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140137297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Page F, Randrianarison V, Marot D, Cabannes J, Perricaudet M, Feunteun J, Sarasin A. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are necessary for the transcription-coupled repair of the oxidative 8-oxoguanine lesion in human cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5548–5552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reardon JT, Bessho T, Kung HC, Bolton PH, Sancar A. In vitro repair of oxidative DNA damage by human nucleotide excision repair system: possible explanation for neurodegeneration in xeroderma pigmentosum patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9463–9468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni TT, Marsischky GT, Kolodner RD. MSH2 and MSH6 are required for removal of adenine misincorporated opposite 8-oxo-guanine in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 1999;4:439–444. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wyrzykowski J, Volkert MR. The Escherichia coli methyl-directed mismatch repair system repairs base pairs containing oxidative lesions. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1701–1704. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.5.1701-1704.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: induction, repair and significance. Mutat Res. 2004;567:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zastawny TH, Altman SA, Randers-Eichhorn L, Madurawe R, Lumpkin JA, Dizdaroglu M, Rao G. DNA base modifications and membrane damage in cultured mammalian cells treated with iron ions. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00241-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halliwell B, Dizdaroglu M. The measurement of oxidative damage to DNA by HPLC and GC/MS techniques. Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;16:75–87. doi: 10.3109/10715769209049161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayala-Torres S, Chen Y, Svoboda T, Rosenblatt J, Van Houten B. Analysis of gene-specific DNA damage and repair using quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Methods. 2000;22:135–147. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grimaldi KA, Bingham JP, Hartley JA. PCR-based assays for strand-specific measurement of DNA damage and repair. I. Strand-specific quantitative PCR. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;113:227–240. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-675-4:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phoa N, Epe B. Influence of nitric oxide on the generation and repair of oxidative DNA damage in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:469–475. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klungland A, Rosewell I, Hollenbach S, Larsen E, Daly G, Epe B, Seeberg E, Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Accumulation of premutagenic DNA lesions in mice defective in removal of oxidative base damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13300–13305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osterod M, Hollenbach S, Hengstler JG, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, Epe B. Age-related and tissue-specific accumulation of oxidative DNA base damage in 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (Ogg1) deficient mice. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1459–1463. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishimura S. Mammalian Ogg1/Mmh gene plays a major role in repair of the 8-hydroxyguanine lesion in DNA. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;68:107–123. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)68093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jensen A, Calvayrac G, Karahalil B, Bohr VA, Stevnsner T. Mammalian 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 incises 8-oxoadenine opposite cytosine in nuclei and mitochondria, while a different glycosylase incises 8-oxoadenine opposite guanine in nuclei. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19541–19548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Imai K, Nakata K, Kawai K, Hamano T, Mei N, Kasai H, Okamoto T. Induction of 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 gene expression by HIV-1 Tat. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeong HG, Youn CK, Cho HJ, Kim SH, Kim MH, Kim HB, Chang IY, Lee YS, Chung MH, You HJ. Metallothionein-III prevents gamma-ray-induced 8-oxoguanine accumulation in normal and hOGG1-depleted cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34138–34149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu T, Pan Y, Kao SY, Li C, Kohane I, Chan J, Yankner BA. Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature. 2004;429:883–891. doi: 10.1038/nature02661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paz-Elizur T, Elinger D, Leitner-Dagan Y, Blumenstein S, Krupsky M, Berrebi A, Schechtman E, Livneh Z. Development of an enzymatic DNA repair assay for molecular epidemiology studies: Distribution of OGG activity in healthy individuals. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramos JM, Ruiz A, Colen R, Lopez ID, Grossman L, Matta JL. DNA repair and breast carcinoma susceptibility in women. Cancer. 2004;100:1352–1357. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnson JM, Latimer JJ. Analysis of DNA repair using transfection-based host cell reactivation. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;291:321–335. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-840-4:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu W, Feng Z, Tang MS. Chromium(VI) enhances (+/−)-anti-7beta,8alpha-dihydroxy-9alpha,10alpha-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydro benzo[a] pyrene-induced cytotoxicity and mutagenicity in mammalian cells through its inhibitory effect on nucleotide excision repair. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14282–14289. doi: 10.1021/bi048560o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vogel U, Dybdahl M, Frentz G, Nexo BA. DNA repair capacity: inconsistency between effect of over-expression of five NER genes and the correlation to mRNA levels in primary lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 2000;461:197–210. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hallberg LM, Bechtold WE, Grady J, Legator MS, Au WW. Abnormal DNA repair activities in lymphocytes of workers exposed to 1,3-butadiene. Mutat Res. 1997;383:213–221. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McKay BC, Rainbow AJ. Heat-shock enhanced reactivation of a UV-damaged reporter gene in human cells involves the transcription coupled DNA repair pathway. Mutat Res. 1996;363:125–135. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(96)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei Q, Matanoski GM, Farmer ER, Hedayati MA, Grossman L. DNA repair related to multiple skin cancers and drug use. Cancer Res. 1994;54:437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hall J, English DR, Artuso M, Armstrong BK, Winter M. DNA repair capacity as a risk factor for non-melanocytic skin cancer--a molecular epidemiological study. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:179–184. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Protic-Sabljic M, Kraemer KH. Host cell reactivation by human cells of DNA expression vectors damaged by ultraviolet radiation or by acid-heat treatment. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:1765–1770. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.10.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun Y, Moses RE. Reactivation of psoralen-reacted plasmid DNA in Fanconi anemia, xeroderma pigmentosum, and normal human fibroblast cells. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1991;17:229–238. doi: 10.1007/BF01232819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Athas WF, Hedayati MA, Matanoski GM, Farmer ER, Grossman L. Development and field-test validation of an assay for DNA repair in circulating human lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5786–5793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Loechler EL, Green CL, Essigmann JM. In vivo mutagenesis by O6-methylguanine built into a unique site in a viral genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:6271–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gentil A, Renault G, Madzak C, Margot A, Cabral-Neto JB, Vasseur JJ, Rayner B, Imbach JL, Sarasin A. Mutagenic properties of a unique abasic site in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:704–710. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moriya M, Ou C, Bodepudi V, Johnson F, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. Site-specific mutagenesis using a gapped duplex vector: a study of translesion synthesis past 8-oxodeoxyguanosine in E. coli. Mutat Res. 1991;254:281–288. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90067-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Le Page F, Margot A, Grollman AP, Sarasin A, Gentil A. Mutagenicity of a unique 8-oxoguanine in a human Ha-ras sequence in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2779–2784. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.11.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koehl P, Burnouf D, Fuchs RP. Construction of plasmids containing a unique acetylaminofluorene adduct located within a mutation hot spot. A new probe for frameshift mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 1989;207:355–364. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burnouf D, Koehl P, Fuchs RP. Single adduct mutagenesis: strong effect of the position of a single acetylaminofluorene adduct within a mutation hot spot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4147–4151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wagner J, Kamiya H, Fuchs RP. Leading versus lagging strand mutagenesis induced by 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:302–309. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boiteux S, le Page F. Repair of 8-oxoguanine and Ogg1-incised apurinic sites in a CHO cell line. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;68:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)68092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O'Connor TR. The use of DNA glycosylases to detect DNA damage. In: Pfeifer GP, editor. Technologies for Detection of DNA Damage and Mutations. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boiteux S, O'Connor TR, Lederer F, Gouyette A, Laval J. Homogeneous Escherichia coli FPG protein. A DNA glycosylase which excises imidazole ring-opened purines and nicks DNA at apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3916–3922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O'Connor TR, Laval J. Physical association of the 2,6-diamino-4-hydroxy-5N-formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase of Escherichia coli and an activity nicking DNA at apurinic/apyrimidinic sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5222–5226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang G, Wang J, Konigsberg W. Base selectivity is impaired by mutants that perturb hydrogen bonding networks in the RB69 DNA polymerase active site. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3338–3346. doi: 10.1021/bi047921x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J, Sattar AK, Wang CC, Karam JD, Konigsberg WH, Steitz TA. Crystal structure of a pol alpha family replication DNA polymerase from bacteriophage RB69. Cell. 1997;89:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Karam JD, Konigsberg WH. DNA polymerase of the T4-related bacteriophages. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2000;64:65–96. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)64002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ye N, Holmquist GP, O'Connor TR. Heterogeneous repair of N-methylpurines at the nucleotide level in normal human cells. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:269–285. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stary A, Menck CF, Sarasin A. Description of a new amplifiable shuttle vector for mutagenesis studies in human cells: application to N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced mutation spectrum. Mutat Res. 1992;272:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(92)90038-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]