Abstract

Context

Sustained-release naltrexone implants may improve outcomes of nonagonist treatment of opioid addiction.

Objective

To compare outcomes of naltrexone implants, oral naltrexone hydrochloride, and nonmedication treatment.

Design

Six-month double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial.

Setting

Addiction treatment programs in St Petersburg, Russia.

Participants

Three hundred six opioid-addicted patients recently undergoing detoxification.

Interventions

Biweekly counseling and 1 of the following 3 treatments for 24 weeks: (1) 1000-mg naltrexone implant and oral placebo (NI+OP group; 102 patients); (2) placebo implant and 50-mg oral naltrexone hydrochloride (PI+ON group; 102 patients); or (3) placebo implant and oral placebo (PI+OP group; 102 patients).

Main Outcome Measure

Percentage of patients retained in treatment without relapse.

Results

By month 6, 54 of 102 patients in the NI+OP group (52.9%) remained in treatment without relapse compared with 16 of 102 patients in the PI+ON group (15.7%) (survival analysis, log-rank test, P<.001) and 11 of 102 patients in the PI+OP group (10.8%) (P<.001). The PI+ON vs PI+OP comparison showed a nonsignificant trend favoring the PI+ON group (P=.07). Counting missing test results as positive, the proportion of urine screening tests yielding negative results for opiates was 63.6% (95% CI, 60%-66%) for the NI+OP group; 42.7% (40%-45%) for the PI+ON group; and 34.1% (32%-37%) for the PI+OP group (P<.001, Fisher exact test, compared with the NI+OP group). Twelve wound infections occurred among 244 implantations (4.9%) in the NI+OP group, 2 among 181 (1.1%) in the PI+ON group, and 1 among 148 (0.7%) in the PI+OP group (P=.02). All events were in the first 2 weeks after implantation and resolved with antibiotic therapy. Four local-site reactions (redness and swelling) occurred in the second month after implantation in the NI+OP group (P=.12), and all resolved with antiallergy medication treatment. Other nonlocal-site adverse effects were reported in 8 of 886 visits (0.9%) in the NI+OP group, 4 of 522 visits (0.8%) in the PI+ON group, and 3 of 394 visits (0.8%) in the PI+ON group; all resolved and none were serious. No evidence of increased deaths from overdose after naltrexone treatment ended was found.

Conclusions

The implant is more effective than oral naltrexone or placebo. More patients in the NI+OP than in the other groups develop wound infections or local irritation, but none are serious and all resolve with treatment.

Naltrexone hydrochloride competitively blocks μ-opioid receptors and reduces or eliminates the positive reinforcing effects of opioids. One 50-mg tablet blocks these effects for 24 to 36 hours; tolerance and withdrawal do not occur; and the medication prevents relapse if taken daily,1,2 unless high doses of opioid are used.3 Unfortunately, adherence to the treatment regimen has been poor except in highly motivated patients,4,5 when family members monitor adherence,6 or when patients face incarceration or job loss if they relapse.2,7 A Cochrane review of sustained-release naltrexone for opioid dependence published in 2008 concluded that evidence was insufficient to evaluate its effectiveness,8 but the review was conducted before publication of a more recent study showing significantly better outcomes with sustained-release injected naltrexone than a control treatment9 and before publication of the findings from the study reported herein. An updated Cochrane review of oral naltrexone published in 2011 concluded that maintenance treatment with naltrexone has not been proven superior to other kinds of treatment.10 However, this review was somewhat internally inconsistent in that the review described findings from the previous studies, in which oral naltrexone was superior to control treatments when used in situations where adoption of naltrexone was facilitated by personal or cultural factors.

One setting where the cultural situation facilitates adoption of naltrexone treatment for opioid dependence is the Russian Federation, where naltrexone is the only effective medication approved for preventing relapse. Addiction treatment in Russia typically begins with 7 to 10 days of inpatient detoxification in specialized addiction (narcology) hospitals using clonidine hydrochloride or other nonopioid medications followed by 2 to 4 weeks of inpatient therapy that includes relaxation and counseling. Patients are referred to a primary health care provider or health center after discharge, but most do not keep appointments. Relapse rates are high and patients are readmitted to repeat the same treatment in attempts to achieve sustained remission. Many patients are young and live with family members who can monitor and enforce adherence, which likely contributed to the positive results in 2 prior studies of oral naltrexone where only 10% to 12% of the placebo control group remained in treatment and did not relapse compared with 42% to 44% of the oral naltrexone group.11,12

Sustained-release formulations might improve these results, and the following 2 formulations have been approved: extended-release naltrexone,9 administered as a monthly injection and approved by theUS Food and Drug Administration for preventing relapse to opioid dependence in 2010; and an implant that blocks opioid effects for 60 to 90 days and is registered in the Russian Federation. 13 Another extended-release injected product that was developed but is no longer available increased retention in a study of 60 patients who were randomized to 192- or 384-mg doses or matching placebo with a second injection a month later.14 Clinicians in Australia developed an extended-release implant that contains 2.3 g of naltrexone and is inserted subcutaneously every 6 months. The product is not registered but is manufactured under the Therapeutic Goods Administration Good Manufacturing Practice in a purpose-built facility inspected and approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration of Australia (Gary Hulse, PhD, personal communication, September 2011). The implant reduced relapse in a study of 70 opioid-addicted patients who were randomized to the implant formulation or to oral naltrexone, 15 and in another study where 56 patients seeking nonagonist treatment were randomized to receive the implant before inpatient discharge or to usual outpatient follow-up care.16

Herein we present the results of a 6-month trial undertaken in Russia among 306 consenting, opioidaddicted patients who had undergone detoxification within the last 1 to 2 weeks. We compare the Russian extended-release implant with oral naltrexone and placebo. All patients received biweekly drug counseling. Our main objective was to assess the degree to which the 3 conditions retained patients in treatment and prevented relapse; secondary outcomes included negative results of opioid urine tests, relapse after treatment ended, and safety.

We hypothesized that patients who received the naltrexone implant would experience more retention and less opioid use and relapse than those receiving oral naltrexone or placebo, and that patients receiving oral naltrexone would have better outcomes than the placebo group. The trial was conducted in outpatient units at Pavlov State Medical University, St Petersburg (Pavlov), and the Leningrad Regional Addiction Treatment and Research Center, affiliated with Pavlov.

The study was conducted according to guidelines in the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the ethical review board at Pavlov and the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania before recruitment commenced; each committee reviewed its progress and reapproved it annually. A University of Pennsylvania staff member who is fluent in Russian and English checked the consent forms to verify that their contents were identical. Written informed consent in Russian was obtained before enrollment, and patients were free to withdraw from the study at any time without jeopardizing their access to other treatments. The principal investigator (G.E.W.) maintained weekly to monthly contact with Russian investigators via e-mail, Skype, and meetings (College on Problems of Drug Dependence and National Institute on Drug Abuse/Pavlov meetings in St Petersburg) to check study progress and visited the research sites on 4 occasions during the course of the study, when he viewed study case report forms, talked to patients, and observed study procedures.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, 24-week trial in which patients received biweekly drug counseling and (1) a bimonthly implant with naltrexone, 1000 mg, and daily oral naltrexone placebo (NI+OP group), (2) a bimonthly placebo implant and oral naltrexone hydrochloride, 50 mg/d (PI+ON group), or (3) a bimonthly placebo implant and daily oral naltrexone placebo (PI+OP group). Patients underwent assessment every 2 weeks during treatment with follow-up at months 9 and 12 for those who remained in treatment without relapse. The first patient was randomized on July 31, 2006; the last visit, January 4, 2009; and the last followup, June 10, 2009.

PARTICIPANTS

Inclusion criteria consisted of ages 18 to 40 years; DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence with physiological features for at least 1 year as determined by results of clinical examination and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview17; abstinence from heroin and other substances for the past week or more; negative results of urine toxicology and alcohol breath tests; no psychotropic medication; ability to provide informed consent; 1 or more relatives or significant others who are willing to encourage medication therapy adherence and provide follow-up information if contacted by research staff; agreement to allow research staff to contact these individual(s); stable address in the St Petersburg/Leningrad region; ability to provide a home telephone number; negative pregnancy test results and use of adequate contraception for women of childbearing age; and negative results of a naloxone challenge. Exclusion criteria included a major psychiatric disorder (ie, dementia, schizophrenia, paranoia, bipolar disorder, or seizure disorder); advanced neurological, cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic disease; active tuberculosis or current febrile illness; AIDSdefining illness; significant laboratory abnormality (severe anemia, unstable diabetes, alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase [ALT/AST] levels of >3 times the top reference limit); pending incarceration; and participation in another treatment study or substance abuse program.

SCREENING: NALOXONE CHALLENGE AND ENROLLMENT

Clinical staff on inpatient units at the St Petersburg City Addiction Hospital and the Leningrad Regional Center for Addictions referred potential subjects to research assistants whowere assigned to these units; a few (n=25) were referred by local practitioners after completing outpatient detoxification. Research assistants explained the study, obtained informed consent, and scheduled appointments for additional screening at 1 of the 2 outpatient sites.

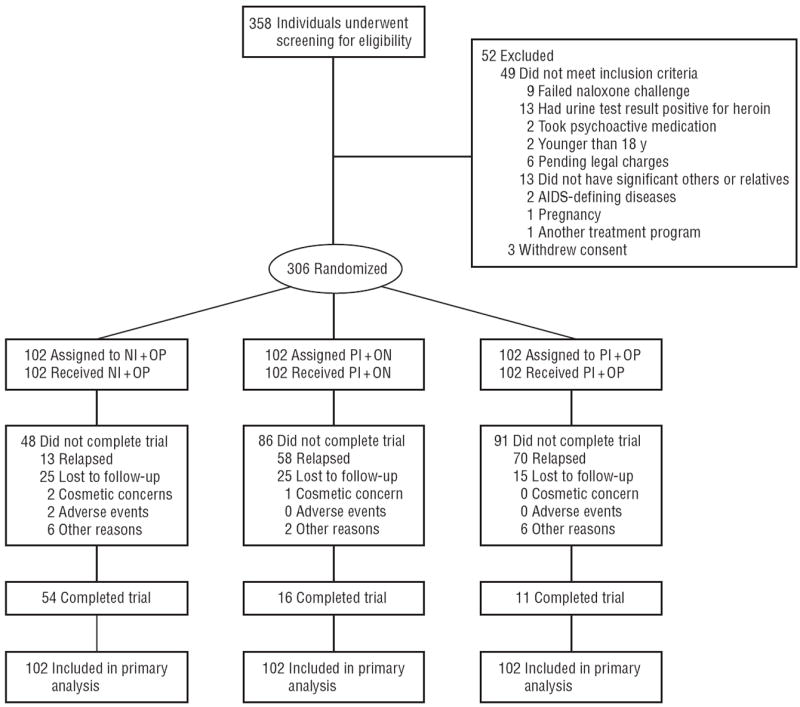

Three hundred fifty eight patients reported for outpatient screening where the medical history and laboratory test results from their recent addiction treatment were checked to confirm eligibility and a urine sample was obtained for drug screening. If the result of the urine screening was negative for opioids and no evidence of physiological dependence or other exclusionary criteria was found, the patient was scheduled for a naloxone challenge and the first dose of study medications. Among the 52 who were excluded from participation, 13 did not have relatives or significant others who could supervise them and provide follow-up information. Patient flow, including reasons for study exclusion, is seen in Figure 1. Those patients found ineligible were referred to usual treatment.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. NI+OP indicates 1000-mg naltrexone implantandoral placebo; PI+NO, placebo implant and 50-mg oral naltrexone hydrochloride; PI+OP, placebo implant and oral placebo. The 2 adverse events in the NI+OP group include wound infection only.

The naloxone challenge was administered in a room set aside for minor surgical procedures at a time that a study surgeon was available to insert the implant. On arrival, the patient was given another urine drug test and checked for signs or symptoms of opioid dependence. Those with a urine test result negative for opioids and no evidence of dependence were given 0.8 mg of naloxone intramuscularly and observed for 1 hour. Those who experienced withdrawal were treated symptomatically and invited to return in 2 to 3 days for a repeat challenge. Failure to pass the challenge on 3 occasions disqualified patients from study enrollment.

Those who passed the challenge underwent randomization. The surgeon inserted the implant, the first dose of oral medication was administered, and the patient was given an appointment for outpatient counseling and a 1-month supply of tablets for availability in case the appointment was missed. At each counseling session, patients were asked if they had used opiates (heroin) since the last appointment, given a urine drug test, and observed for signs of withdrawal or recent use. Relatives often accompanied patients and provided information to supplement selfreports or were contacted by telephone to determine patient status in case of missed appointments. A naloxone challenge was repeated if a urine test result was positive for opioids or other evidence of relapse; patients who showed evidence of relapse were referred to usual treatment and not eligible to continue to receive study medication. Others were given a 2-week supply of study tablets and scheduled for the next counseling session. A naloxone challenge was repeated before each implantation unless clear evidence indicated relapse.

INTERVENTIONS

Implant Naltrexone and Implant Placebo Naltrexone

The implant contains 1000 mg of naltrexone embedded in a magnesium stearate matrix with a small dose of triamcinolone acetonide added to prevent inflammation. The implant is inserted under the skin of the abdominal wall to a depth of 3 to 4 cm using a sterile, prepackaged disposable syringe through a 1- to 2-cm incision that is closed with 1 to 2 sutures. Plasma levels during 30 to 60 days are 20 ng/mL for naltrexone and 60 ng/mL for 6β-naltrexol, naltrexone’s active metabolite.18 This implant has been shown to block opioids for 2 months, is biodegradable, and does not require removal.18

Oral Naltrexone and Oral Placebo

Pavlov pharmacy staff made visually identical oral naltrexone and placebo capsules containing a 50-mg riboflavin marker for monitoring adherence. Studies of 50-mg tablets have shown plasma levels peaking in 1 to 3 hours at 10.0 to 20.0 ng/mL and declining to approximately 0.5 to 1.0 ng/mL at 24 hours with a half-life of 4 hours; 6β-naltrexol reached roughly 8 times the peak naltrexone concentration and declined with a half-life of about 14 hours.19,20

Blinding

Pavlov pharmacy staff prepared medication kits containing the oral and implant medication combinations for individual patients, placed them in numbered containers, and transported them to outpatient sites. Research assistants, treating physicians, other project staff, and participants were blind to group assignment. Amaster code was kept off-site, and the blind could be broken in case of emergency (this option was never used). Formal procedures to assess the success of blinding were not undertaken.

Randomization

Randomization was completed in the data management unit at Pavlov using a generator of random numbers into commercially available software (SPSS, version 17; SPSS, Inc).

Individual Drug Counseling

Individual drug counseling was based on a modified version of the treatment used in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study21 as described on the National Institute on Drug Abuse web site (http://archives.drugabuse.gov/TXManuals/IDCA/IDCA16.html). Modifications involved emphasizing adherence to medication and counseling, dealing with persistent withdrawal, and deemphasizing self-help group participation because it is not widely used in St Petersburg. The manual was revised to reflect these changes and translated into Russian. Therapists were experienced masters’ level psychologists and addiction psychiatrists (narcologists) and were provided with a copy of the manual, given an overview of counseling techniques by the manual’s authors, and supervised by one of us (E.K.). All patients received human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk reduction information as part of usual treatment before enrolling in the study. Counseling sessions lasted about 45 minutes and were not recorded or rated for adherence.

MEASURES

Routine blood tests (complete blood cell counts, electrolytes, and levels of ALT/AST) and urinalysis were completed as part of usual treatment before study enrollment. Assessments added for the study included a detailed history of drug use and psychiatric interview to confirm current opioid dependence; urine testing for opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, marijuana, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates; alcohol breath test; Addiction Severity Index22; Risk Assessment Battery23; Time Line Follow-Back for alcohol and drugs24; pregnancy test; monthly measurements of ALT and AST levels while receiving medication; heroin craving (visual analog scale); Global Assessment of Functioning25; Beck Depression Inventory26; Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale27; Spielberger State- Trait Anxiety Test28; Scale of Protracted Withdrawal Syndrome29; Chapman Scale of Physical and Social Anhedonia30; Ferguson Anhedonia Scale31; and visual inspection of the site 5 to 7 days after implantation. No measure for differences in swelling, redness, and tenderness was used. Urine drug testing was performed at biweekly counseling sessions.

Adherence to the tablet regimen was assessed by pill counts at each appointment, visual inspection for the presence of riboflavin in the urine using UV light at 444 nm in a room with low ambient light, and information from the family member or significant other whom the patient agreed to allow research staff to contact.

Interviews and urine drug screens were completed at 9 and 12 months to assess for relapse in patients who remained in treatment and did not relapse. Patient safety was assessed by inspection of the implant site 5 to 7 days after implantation and at subsequent visits, asking patients if they were having problems at biweekly counseling sessions, testing for liver enzyme levels at week 24, and contacting patients or significant others approximately 18 months after randomization to find out if they were alive and, if not, the cause of death.

Patients were counted as early terminators if they missed more than 2 consecutive biweekly appointments and as having a relapse if they reported daily heroin use, had signs and symptoms of withdrawal, or a positive result of a naloxone challenge. Patients who reported occasional heroin use but did not have physiological dependence were considered to have had a slip rather than a relapse and continued to receive study medication if they passed a naloxone challenge. Patients were reimbursed for time and transportation with the ruble equivalent of $10 for each study visit for a total of $120 if all study appointments were kept.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were double entered and checked for errors and analyzed using commercially available software (SPSS, version 17; SPSS, Inc). Survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier survival functions with log-rank Cox-Mantel criteria for group comparison32) was used to determine the primary outcome of retention, defined as not missing 2 consecutive counseling sessions and not having a relapse. Because this outcome combined patients who failed to keep appointments with those who kept appointments but relapsed, the proportion of nonsurvivors attributable to proven relapse was also determined. Secondary outcomes reported herein are the cumulative percentages of negative results of urine screening for opiates during the 24-week medication phase, relapse at 9 and 12 months among patients who completed treatment without relapse and returned for follow-up, and safety. Safety assessments included adverse effects (AEs) using Fisher exact tests with Monte-Carlo modeling for more than 2 groups, liver enzyme levels at 24 weeks, and overdose deaths 18 months after randomization.

The sample size provided 80% power to detect a difference of 20% or greater between the groups for the primary outcome assuming an α value of .025 (2 contrasts) and a survival rate of approximately 60% in the NI+OP group. The major study statistician (E.V.) was not blinded to group assignment; however, another statistician who was blinded to group assignment and working on genetics issues of this study verified the major biostatistician’s findings on survival analyses and urine test results (Nina Alexeyeva, PhD, personal communication, September 2011).

RESULTS

DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL FEATURES

All patients were dependent on intravenous heroin; prescription opioids are highly restricted, expensive, and difficult to obtain in Russia. Patients’ mean (SE) age was 28.2 (0.2) years; most (n=222 [72.5%]) were male; average (SE) duration of opioid dependency was 8.0 (0.2) years; and average number of previous treatments ranged from 3.8 to 4.9. Among 306 study patients, the baseline assessment showed that 144 (47.1%) were seropositive for HIV; 292 (95.4%) were seropositive for hepatitis C virus; and 47 (15.4%) were seropositive for hepatitis B virus. Past 30-day self-reported substance use at baseline showed that 82 (26.8%) used marijuana; 36 (11.8%), amphetamines; 34 (11.1%), sedatives, mostly benzodiazepines; and none, cocaine. Average (SD) alcohol use was 9.6 (1.0) g/d. There were no significant baseline differences between groups in demographics or clinical variables.

ORAL MEDICATION ADHERENCE

Urine samples were collected biweekly from patients who remained in treatment; the proportion of riboflavinpositive samples varied from 70% to 100%. These data were consistent with capsule counts and information from informants, indicating that those who remained in treatment were taking the oral study medication.

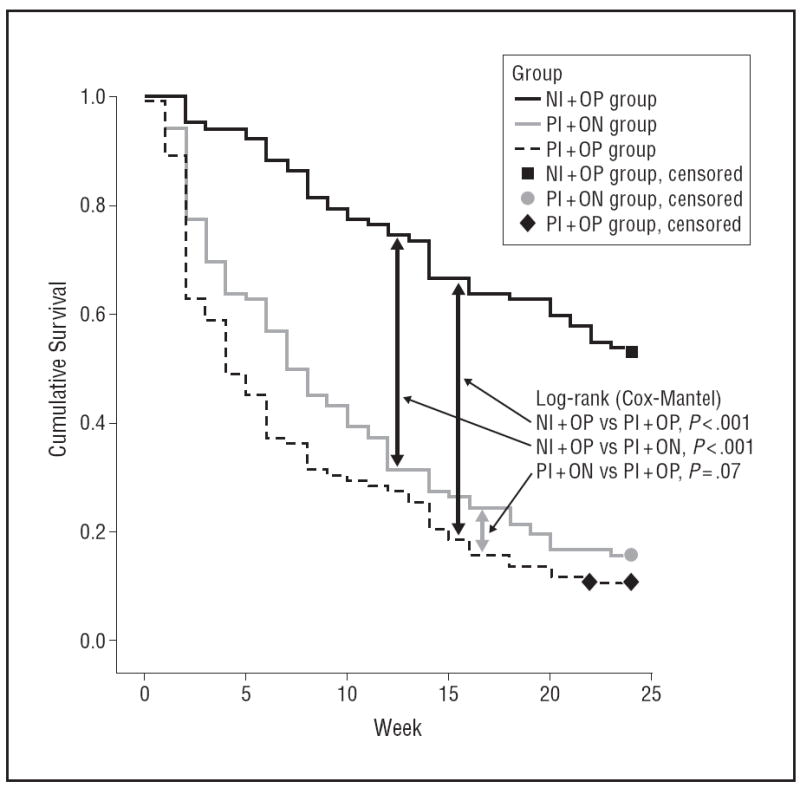

PRIMARY OUTCOME: RETENTION WITHOUT RELAPSE

By month 6, 54 of 102 patients in the NI+OP group (52.9%) remained in treatment without relapse, compared with 16 of 102 patients in the PI+ON group (15.7%) and 11 of 102 patients in the PI+OP group (10.8%). Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for these comparisons. Log-rank tests showed a significant overall effect for treatment group (log-rank statistic, 62.16; df=2 [P<.001]). We found significant differences between the NI+OP and PI+OP groups (logrank statistic, 68.4; df=1 [P<.001]) and between the NI+OP and PI+ON groups (log-rank statistic, 45.2; df=1 [P<.001]). The PI+ON vs PI+OP comparison showed a nonsignificant trend favoring oral naltrexone (logrank test, 3.44; df=1 [P=.07]), as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival evaluating treatment dropout and relapse.

NI+OP indicates 1000-mg naltrexone implantandoral placebo (n=102);

PI+NO, placebo implant and 50-mg oral naltrexone hydrochloride (n=102);

PI+OP, placebo implant and oral placebo (n=102).

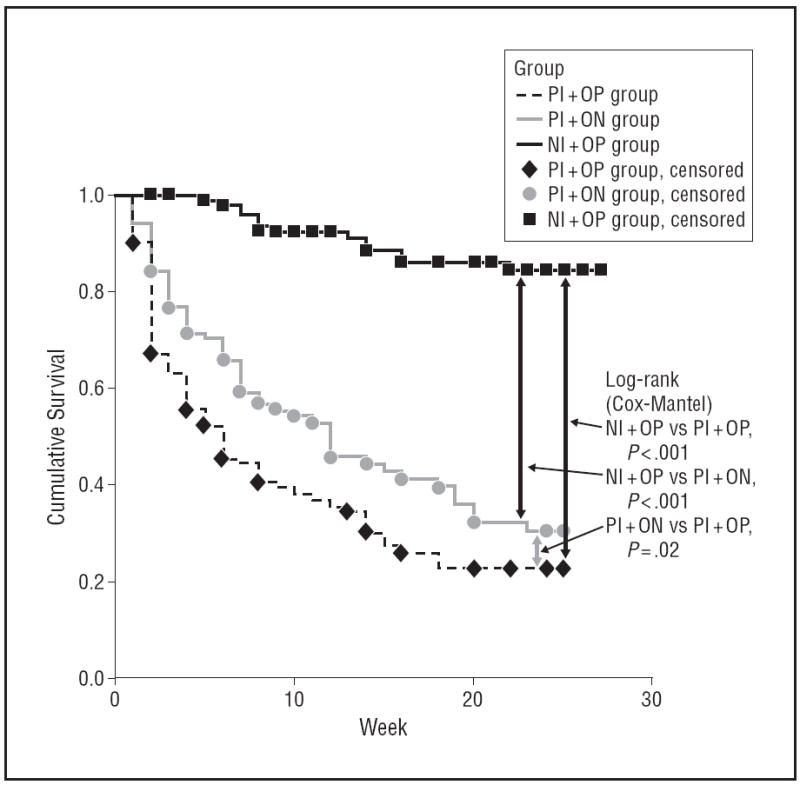

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the event of verified relapse. The results were very similar to those in Figure 2; however, in this analysis we found a significant difference between the PI+ON and PI+OP groups (log-rank test, 5.08; df=1 [P=.02]).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival evaluating verified relapse. NI+OP indicates 1000-mg naltrexone implantandoral placebo (n=102); PI+NO, placebo implant and 50-mg oral naltrexone hydrochloride (n=102); PI+OP, placebo implant and oral placebo (n=102).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

Opiate Urine Test Results

Results of missed urine tests were imputed to be positive for opiates. The cumulative urine tests with results negative for opiates in the NI+OP group was 908 of 1428 (63.6%), significantly greater than in the PI+ON (610 of 1428 [42.7%]; odds ratio, 0.43 [95% CI, 0.38-0.50; P<.001]) and PI+OP groups (487 of 1428 [34.1%]; odds ratio, 0.30 [95% CI, 0.25-0.35; P<.001]). The cumulative proportion of urine tests with results negative for opiates in the PI+ON group was greater than in the PI+OP group (odds ratio, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.60-0.81; P<.001]). The results of self-reported opiate use were very similar to the urine drug test results.

Relapse at Follow-up

At 9 months, 35 of 306 patients returned for follow-up assessments. Among these, 20 were in the NI+OP group (12 of 102 in remission), 7 in the PI+ON group (4 of 102 in remission [P=.14]), and 8 in the PI+OP group (5 of 102 in remission [P=.07]). At 12 months, 28 of the 306 patients underwent assessment and among these, 16 were in the NI+OP group (7 of 102 in remission); 6, the PI+ON group (2 of 102 in remission [P=.17]); and 6, the PI+OP group (3 of 102 in remission [P=.33]).

Safety

Adverse events at the implant site were wound infections and local reactions (redness and swelling). Infections were observed in 9 of 102 patients (8.8%) in the NI+OP group (twice in 3 patients, after the first and second implantations); in 2 of 102 patients (2.0%) in the PI+ON group (P=.02, Fisher exact test); and in 1 of 102 patients (1.1%) in the PI+OP group (P=.008, Fisher exact test). Because the number of implantations was different in each group owing to attrition, we calculated AEs per number of implantations. Results were 12 wound infections of 244 implantations (4.9%) in the NI+OP group, 2 of 181 implantations (1.1%) in the PI+ON group (P=.02, Fisher exact test), and 1 of 148 implantations (0.7%) in PI+OP group (P=.02, Fisher exact test). All infections were observed within the first 2 weeks after implantation and successfully treated with antibiotics within 1 week; however, 2 patients in the NI+OP group left the study owing to wound infections. Four patients had local-site reactions (redness and swelling), all in the NI+OP group (P=.12, Fisher exact test). All were observed in the second month after implantation and successfully treated with chloropyramin (an antiallergic medication) during the next month. Other (nonlocal-site) AEs among patients who remained in treatment were reported by 8 of 102 patients in the NI+OP group (7.8%), 4 of 102 patients in the PI+ON group (3.9) (P=.19 compared with the NI+OP group, Fisher exact test), and 3 of 102 patients in the PI+OP group (2.9%) (P=.1 compared with the NI+OP group, Fisher exact test). However, more NI+OP than PI+ON or PI+OP patients remained in treatment. Thus, nonlocal-site AEs were reported in 8 of 886 visits in the NI+OP group (0.9%), 4 of 522 in the PI+ON group (0.7%), and 3 of 394 in the PI+ON group (0.8%) (all differences were nonsignificant). The most common AEs were abdominal discomfort, nausea, and drowsiness. Most AEs were in the first 3 months; none were severe; and all resolved without medication. The only known severe AE during the treatment phase was a cholecystectomy in the PI+OP group.

At baseline, the mean ALT level varied from 45.9 to 54.1(SE, 3.08) IU/L and AST, from 45.8 to 52.6 (SE, 2.58) IU/L with no significant differences between groups (to convert ALT and AST to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167). End of treatment measures were only available for patients who remained in treatment and did not relapse. For these patients, ALT levels varied from 47.4 to 96.5 (SE, 8.84) IU/L and AST, from 43.2 to 89.5 (SE, 8.3) IU/L; differences were not significant across groups or from baseline to 6 months. We found no evidence of increased risk of death due to overdose after naltrexone treatment.33

COMMENT

Methadone is a schedule I drug in Russia, and the Ministry of Health has not accepted Western data on the benefits of agonist maintenance therapy. This approach is similar in many ways to the United States from the mid- 1920s to late 1960s, when physicians could lose their licenses or be arrested and jailed if they used opioids to treat opioid addicts. However, unlike the United States during those years, Russia has committed significant resources to detoxification and residential treatment. For example, state-supported alcohol and drug treatment is provided in 138 dispensaries (115 of which have inpatient units) and 12 addiction hospitals with more than 25 000 beds in total and from 50 to 2000 beds per hospital depending on the region. In addition, several hundred commercial and nongovernmental organizations and more than 5600 psychiatrist-narcologists work in the addiction field (Evgenia Koshkina, MD, PhD, personal communication, September 2011). This treatment is readily available, as seen in the Table, where study patients averaged 4 to 5 prior treatment episodes.

Table.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristicsa

| Medication Group

|

All Patients (n = 306) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NI+OP (n = 102) | PI+ON (n = 102) | PI+OP (n = 102) | ||

| Age, y | 28.0 (0.4) | 27.9 (0.4) | 28.7 (0.5) | 28.2 (0.2) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||

| Male | 74 (72.5) | 74 (72.5) | 74 (72.5) | 222 (72.5) |

| Female | 28 (27.5) | 28 (27.5) | 28 (27.5) | 84 (27.5) |

| Duration of heroin abuse, y | 7.8 (0.4) | 7.9 (0.4) | 8.3 (0.4) | 8.0 (0.2) |

| Average dose of heroin, mg/d | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.04) |

| Use of amphetamines, No. (%) | 12 (11.8) | 6 (5.9) | 18 (17.6) | 36 (11.8) |

| Use of cocaine, No. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Use of marijuana, No. (%) | 35 (34.3) | 22 (21.6) | 25 (24.5) | 82 (26.8) |

| Use of sedatives or benzodiazepines, No. (%) | 15 (14.7) | 10 (9.8) | 9 (8.8) | 34 (11.1) |

| Use of alcohol, g/d | 10.2 (1.7) | 9.0 (1.7) | 9.6 (1.6) | 9.6 (1.0) |

| No. of previous treatments | 4.9 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.2) |

| Employment, No. (%) | 47 (46.1) | 42 (41.2) | 51 (50.0) | 140 (45.8) |

| Seropositive for HIV, No. (%) | 44 (43.1) | 53 (52.0) | 47 (46.1) | 144 (47.1) |

| Seropositive for hepatitis B virus, No. (%) | 18 (17.6) | 16 (15.7) | 13 (12.7) | 47 (15.4) |

| Seropositive for hepatitis C virus, No. (%) | 98 (96.1) | 98 (96.1) | 96 (94.1) | 292 (95.4) |

| RAB drug risk | 8.0 (0.47) | 8.1 (0.44) | 8.7 (0.49) | 8.2 (0.27) |

| GAF score | 64.7 (0.8) | 62.8 (0.7) | 62.5 (0.9) | 63.3 (0.5) |

| ASI subscales | ||||

| Medical problems | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.01) |

| Work problems | 0.68 (0.03) | 0.72 (0.03) | 0.76 (0.03) | 0.73 (0.02) |

| Alcohol use problems | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.01) |

| Drug use problems | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.004) |

| Legal problems | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.01) |

| Family problems | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.31 (0.02) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.32 (0.01) |

| Psychiatric problems | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.02) | 0.17 (0.01) |

Abbreviations: ASI, Addiction Severity Index; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NI+OP, 1000-mg naltrexone implant and oral placebo; PI+ON, placebo implant and 50-mg oral naltrexone hydrochloride; PI+OP, placebo implant and oral placebo; RAB, Risk Assessment Battery.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as mean (SE). Differences between groups were nonsignificant.

Starting naltrexone therapy for these patients and under these conditions is easy because the patients undergo routine detoxification. Study findings show that an extended-release implant can alter the course of the addiction, at least for 6 months in about half the patients; however, the degree to which patients will accept longer courses of treatment is a topic for future studies. Unfortunately naltrexone, in the oral or extendedrelease form, is not widely available in Russia owing to costs, but this situation could change. Whatever the future may bring, patients in this study likely received better treatment than they otherwise would have, including those in the placebo group who received counseling from experienced therapists that was integrated into the study procedures and available immediately after completing detoxification and residential treatment.

Although results clearly favored the implant, patients who received oral naltrexone had fewer urine tests yielding results positive for opiates compared with the placebo group. In addition, the primary outcome showed a nonsignificant trend (P=.07) favoring oral naltrexone compared with placebo that might be significant with a larger sample size. This difference was significant (P=.02) when survival was measured for verified relapse; thus, oral naltrexone appeared to improve on the results of usual treatment with a few patients. These findings differ from earlier Russian studies where patients receiving oral naltrexone treatment had better outcomes than those of the placebo control group starting in the first month and continuing through month 6.11,12 A possible reason for these differences is that the older patients in the implant study (average age, 28.2 years) may have been less influenced by and dependent on close relatives for support than the younger patients (aged 21-23 years) in the earlier oral naltrexone studies. Genetic differences in μ-receptors may also play a role, and we are exploring this possibility in collaboration with other investigators.

These findings are similar to those from the recent trial of sustained-release injected naltrexone, where about half of the patients in the medication group remained in treatment for 6 months and had fewer urine tests with results positive for opioids than the placebo control group.9 From follow-ups on the limited sample of patients who remained in treatment without relapse and who returned for 9- and 12-month follow-ups, we can determine that approximately half relapsed after treatment ended. However, by counting missed appointments as relapses, almost all patients had a relapse, suggesting that for most patients, naltrexone therapy probably needs to be continued for an extended period.

Fourteen patients who received the naltrexone implant (13.7%) experienced a relapse between implantations, and 12 relapses occurred in weeks 6 through 8. The following 5 possibilities might account for this finding: fibrosis around the implant reduced dissemination of naltrexone; the patients metabolized naltrexone rapidly; patients had access to large amounts of high-grade heroin that they used to overcome the blockade as blood levels dropped toward the end of the dosing cycle; the implant released naltrexone more quickly than intended, resulting in low blood levels toward the end of the dosing cycle; or the subcutaneous tissue where the implant was placed did not have enough blood supply to absorb the naltrexone and maintain opioid blockade.

The possibility of patients unmasking the study by using heroin is not as likely as it may appear. In Russia, a sort of placebo effect is associated with getting an injection: patients often think injections are stronger regardless what is injected. In addition, the quality of heroin is sometimes poor, which might reduce the effect of a single heroin injection, and the effect also depends to some extent on expectation and setting. Thus lack of an effect from a single injectionmaynot necessarily be attributable to opioid blockade. In addition, the placebos were not active and had only a visual similarity to the active medication.

Similar to earlier studies, we saw no evidence of increased depression, anxiety, or anhedonia associated with naltrexone.34 In fact these symptoms, along with craving, appeared to drop for patients who continued treatment without relapse, as seen in other naltrexone studies with opioid-dependent patients35,36 and in studies of alcohol-dependent patients treated with extendedrelease injected naltrexone who did not experience dysphoria or lack of pleasurable stimuli.37

Tolerability of the implant was generally good, and no serious AEs attributable to the study medications were reported; however, AEs at the implant site were more common among patients who received the naltrexone implant. This finding could reflect contamination in some of the implants, local irritation caused by naltrexone or other components of the implant, or patients’ attempts to remove the implant, although none were reported. The proportion of other AEs was comparable across groups and also to those in a study using the Australian implant16; however, in that study, 3 of the 56 patients had implants removed at their request.

Previous studies have shown that any effective treatment for opioid dependence reduces risk of HIV due to injections.38 This finding is very relevant to countries such as Russia, where HIV is being spread largely by injected drug use as reflected by these and other data from St Petersburg showing that more than 40% of opiateaddicted patients are seropositive for HIV.39,40 Given the potential for reduction in HIV risk among patients who remained in naltrexone treatment and did not relapse, combined with the apparent unshakable resistance to using agonist therapies in Russia and the widespread availability of inpatient detoxification, naltrexone and in particular extended-release formulations could play a meaningful role in reducing the spread of HIV if the treatment was more readily available throughout the network of state and private treatment facilities.

The limitations of naltrexone implants include the surgical procedure, possibility of wound infection or local irritation, cosmetic defects (scars), need for high opioid doses if the patient develops amedical condition that requires opioid therapy, and possible removal of the implant by the patient within 7 to 14 days after receiving it. Limitations of the study include the limited amount of data on patients who did not remain in treatment, thus making it difficult to obtain more accurate information on the proportions with relapse at 9- and 12-month followups and other secondary outcomes. Strengths include the randomized, prospective, double-dummy design; the large number of participants; involvement of close relatives to provide additional information; and determination of the primary outcome by objective data.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants 1-R01-DA-017317 and KO5 DA-17009 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Dr Woody). Fidelity Capital provided naltrexone implants at reduced cost and placebo implants at no cost. The Zambon Group provided oral naltrexone at reduced cost.

Role of the Sponsors: The funding organization and the companies that provided pharmaceutical products had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional Contributions: Charles O’Brien, MD, PhD, provided helpful comments. Daniel Langleben, MD, PhD, reviewed the Russian consent forms for consistency with the English versions.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Krupitsky is a paid consultant to Alkermes, and Alkermes is providing extendedrelease injectable naltrexone for a study in which Dr Woody is an investigator.

References

- 1.Kleber HD, Kosten TR, Gaspari J, Topazian M. Nontolerance to the opioid antagonism of naltrexone. Biol Psychiatry. 1985;20(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(85)90136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleber HD. Pharmacologic treatments for opioid dependence: detoxification and maintenance options. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9(4):455–470. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.2/hkleber. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krupitsky EM, Burakov AM, Tsoy MV, Egorova VY, Slavina TY, Grinenko AY, Zvartau EE, Woody GE. Overcoming opioid blockade from depot naltrexone (Prodetoxon) Addiction. 2007;102(7):1164–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resnick RB. A practitioner’s experience with naltrexone. Paper presented at: American Society of Addiction Medicine 29th Annual Scientific Conference; April 16-19, 1998; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sevarino KA, Kosten TR. Naltrexone for initiation and maintenance of opiate abstinence. In: Dean R, Bilsky EJ, Negus SS, editors. Opiate Receptors and Antagonists: From Bench to Clinic. New York, NY: Humana; 2009. pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral family counseling and naltrexone for male opioid-dependent patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(3):432–442. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornish JW, Metzger D, Woody GE, Wilson D, McLellan AT, Vandergrift BV, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone pharmacotherapy for opioid dependent federal probationers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14(6):529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobmaier P, Kornør H, Kunøe N, Bjørndal A. Sustained-release naltrexone for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006140.pub2. CD006140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M, Kirchmayer U, Verster A. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001333.pub4. CD001333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krupitsky EM, Zvartau EE, Masalov DV, Tsoi MV, Burakov AM, Egorova VY, Didenko TY, Romanova TN, Ivanova EB, Bespalov AY, Verbitskaya EV, Neznanov NG, Grinenko AY, O’Brien CP, Woody GE. Naltrexone for heroin dependence treatment in St Petersburg, Russia. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26(4):285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krupitsky EM, Zvartau EE, Masalov DV, Tsoy MV, Burakov AM, Egorova VY, Didenko TY, Romanova TN, Ivanova EB, Bespalov AY, Verbitskaya EV, Neznanov NG, Grinenko AY, O’Brien CP, Woody GE. Naltrexone with or without fluoxetine for preventing relapse to heroin addiction in St Petersburg, Russia. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(4):319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanets NN, Anokhina IP, Vinnikova MA. New long-acting drug formulation of naltrexone “Prodetoxone, tablet for implantation” in the combined treatment of patients with opiate dependence [in Russian] Prob Drug Depend. 2005;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Yu E, Rothenberg JL, Kleber HD, Kampman K, Dackis C, O’Brien CP. Injectable sustained-release naltrexone for the treatment of opioid-dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psych. 2006;63(2):210–218. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulse GK, Morris N. Arnold-Reed D, Tait RJ. Improving clinical outcomes in treating heroin dependence: randomized, controlled trial of oral or implant naltrexone. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(10):1108–1115. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunøe N, Lobmaier P, Vederhus JK, Hjerkinn B, Hegstad S, Gossop M, Kristensen Ø, Waal H. Naltrexone implants after in-patient treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(6):541–546. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for the DSM-IV. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kukes VG, Ramenskaya GV, Guseinova CV, Sulimov GY. Pharmacokinetics of new Russian sustained release implantable naltrexone. Novye Lekarstvennye Preparaty. 2006;33(2):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vereby K, Volavka J, Mult SJ, Resnick RB. Naltrexone disposition, metabolism, and effects after acute and chronic dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976;120(2):315–328. doi: 10.1002/cpt1976203315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason BJ, Goodman AM, Dixon RM, Hameed MHA, Hulot T, Wesnes K, Hunter JA, Boyeson MG. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interaction study of acamprosate and naltrexone. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27(4):596–606. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00368-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine JD, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, Muenz L, Thase ME, Weiss RD, Gastfriend DR, Woody GE, Barber JP, Butler SF, Daley D, Bishop S, Najavits LM, Lis J, Mercer D, Griffin ML, Moras K, Beck AT. The National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study: rationale and methods. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(8):721–726. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, O’Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(7):412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navaline HA, Snider EC, Petro C, Tobin D, Metzger D, Alterman AI, Woody GE. Preparations for AIDS vaccine trials: an automated version for the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB): enhancing the assessment of risk behaviors. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses. 1994;10(suppl 2):S281–S283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Time Line Follow-Back: a technique for assessing selfreported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa, NJ: Human Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Substance-related disorders; pp. 175–272. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spielberger CD, Anton WD, Bedell J. In: The Nature and Treatment of Test Anxiety: Emotion and Anxiety: New Concepts, Methods and Applications. Zuckerman M, Spielberger CD, editors. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krupitsky EM, Burakov AM, Romanova TN, Vostrikov VV, Grinenko AY. The syndrome of anhedonia in recently detoxified heroin addicts: assessment and treatment. Abstracts of the International Meeting “Building International Research on Drug Abuse: Global Focus on Youth”; Scottsdale AZ: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85(4):374–382. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson J, Sills T, Evans K, Kalali A. Anhedonia: is there a difference between interest and pleasure?. Poster presented at: American College of Nuclear Physicians Meeting; December 3-7, 2006; Hollywood, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. JAm Statist Assn. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woody GE, Metzger DS. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence. Lancet. 2011;378(9792):664–666. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krupitsky E, Zvartau E, Woody G. Use of naltrexone to treat opioid addiction in a country in which methadone and buprenorphine are not available. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(5):448–453. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0135-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ngo HT, Arnold-Reed DE, Hansson RC, Tait RJ, Hulse GK. Blood naltrexone levels over time following naltrexone implant. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hulse GK, Ngo HT, Tait RJ. Risk factors for craving and relapse in heroin users treated with oral or implant naltrexone. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(3):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Brien CP, Gastfriend DR, Forman RF, Schweizer E, Pettinati HM. Long-term opioid blockade and hedonic response: preliminary data from two open-label extension studies with extended-release naltrexone. Am J Addict. 2011;20(2):106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metzger DS, Navaline H, Woody GE. Drug abuse treatment as AIDS prevention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(suppl 1):97–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krupitsky EM, Zvartau EE, Lioznov DA, Tsoy MV, Egorova VY, Belyaeva TV, Antonova TV, Brazhenko NA, Zagdyn ZM, Verbitskaya EV, Zorina Y, Karandashova GF, Slavina TY, Grinenko AY, Samet JH, Woody GE. Co-morbidity of infectious and addictive diseases in St Petersburg and the Leningrad Region, Russia. Eur Addict Res. 2006;12(1):12–19. doi: 10.1159/000088578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruse GR, Barbour R, Heimer R, Shaboltas AV, Toussova OV, Hoffman IF, Kozlov AP. Drug choice, spatial distribution, HIV risk, and HIV prevalence among injection drug users in St Petersburg, Russia. Harm Reduct J. 2009 Jul 31;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]