Summary

Background:

Splenic rupture is a potentially life-threatening condition, often associated with chest or abdominal trauma. Spontaneous rupture is very rare and is usually reported as being secondary to underlying pathological conditions.

Case Report:

We discuss the case of a 56 year old man who presented with sudden onset left-sided abdominal pain, with no history of trauma.

Conclusions:

A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a ruptured spleen with free fluid in the abdomen. Conservative management was ineffective and the patient underwent laparotomy and splenectomy, followed by routine post-splenectomy management. He was discharged home and remains well.

Keywords: splenic rupture, atraumatic, unknown aetiology

Background

Splenic rupture is a potentially life-threatening condition and the majority of cases are secondary to trauma. Multiple underlying pathologies have also been associated with splenic rupture, including haematological, neoplastic, inflammatory and infectious conditions. Atraumatic splenic rupture rarely occurs [1,2]. Splenic rupture is often not considered in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in the absence of trauma, the results of which may be catastrophic. The first reported cases of atraumatic splenic rupture were by Rokitansky (1861) and Atkinson (1874). Weidemann (1927) first defined ‘spontaneous splenic rupture’ as ‘rupture resulting from an incident without external force.’ Knoblish (1966) distinguished ‘non-traumatic rupture of a pathological spleen’ from the extremely rare ‘non-traumatic splenic rupture of unknown aetiology’ i.e. true ‘spontaneous splenic rupture’ [1,3].

The diagnosis of splenic rupture is a clinical one, confirmed by either CT scan or laparotomy (in haemodynamically unstable patients). Several grading systems based on CT or ultrasound findings have been established for splenic rupture and each has been shown to be useful for guiding management decisions.

There are numerous case reports of spontaneous splenic rupture but a comprehensive assessment of incidence rates, causes, specific symptoms, management options and prognosis has not been performed [3].

Case Report

A 56 year old male patient presented to the emergency department with sudden-onset, severe, left-sided abdominal pain that had woken him from sleep. The pain was associated with nausea but no vomiting. He denied any history of trauma, change in bowel habit or urinary symptoms. He reported 2 episodes of a similar, but much less severe, pain in the preceding week. There was no significant past medical history and he was not on any regular medications.

On initial examination, his pulse was 110bpm, BP 110/78 mmHg, RR 20 and sats 91% on 5l. Chest examination was unremarkable. Abdominal examination showed left-sided tenderness. PR examination was unremarkable. The gentleman’s BP dropped suddenly to 70/40 mmHg and his pulse increased to 130 bpm.

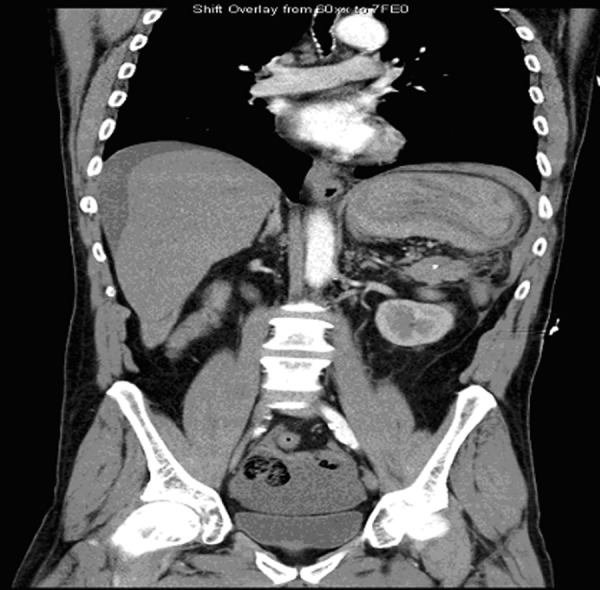

Following initial successful fluid resuscitation, he underwent a CT scan which showed free fluid in the abdomen and a perisplenic haematoma with disruption of the splenic parenchyma (Figure 1). Initial bloods were unremarkable but repeat bloods after 6 hours showed Hb 7.5.

Figure 1.

Coronal section of the Abdominal CT scan shows free fluid in the abdomen and a splenic haematoma.

The splenic injury was initially managed conservatively, including transfusion of 3 units of red blood cells. On re-assessment the abdomen remained tender on the left. As the patient remained haemodynamically unstable, the decision was made to proceed to a splenectomy.

At laparotomy the patient had approximately 2 litres of haemolysed blood in the abdominal cavity and a large perisplenic haematoma with grade IV splenic injury (i.e. the laceration involved the splenic hilum). He was transfused an additional 2 units intra-operatively. Histopathology showed normal splenic tissue and no other underlying pathology.

Post-operatively, the patient received pneumococcal, meningococcal and haemophilus vaccinations and was discharged on life-long penicillin prophylaxis.

Discussion

Atraumatic splenic rupture was first documented in the 19th century. Since then it has been associated with several underlying pathologies, including infectious (e.g. malaria and glandular fever), gastrointestinal (e.g. pancreatitis), haematological (e.g. lymphoma) and systemic (e.g. sarcoidosis) [2,4,5].

In the absence of trauma, diagnosis of splenic rupture is not always made by considering just the classic signs and symptoms of left upper quadrant (LUQ) pain, guarding and haemodynamic instability [3]. As in the case presented, the atraumatic history and absence of underlying pathologies meant that only the symptoms of left-sided abdominal pain (not specifically LUQ pain) and sudden haemodynamic instability raised the suspicion of splenic rupture. Left shoulder-tip pain resulting from diaphragmatic irritation (Kehr’s sign) is reported in approximately 50% of cases [6,7] but was absent in this instance.

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion in diagnosing atraumatic splenic rupture; particularly in a patient with isolated left-sided abdominal pain. Other differentials in such a patient would include cardiac ischaemia, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, peptic ulceration or ruptured sigmoid diverticulitis [6,7].

A CT scan is often essential to make the diagnosis and grade the splenic injury, although an ultrasound scan may be clinically useful. The most common finding on CT is splenomegaly with splenic lacerations and intraperitoneal or subcapsular bleeding [6]. We use a grading system of I–V based on CT findings. This scale considers the size of the splenic laceration and associated haematoma as well as any hilar involvement [8].

Low-grade injuries (I–II) may be managed conservatively, whereas higher-grade (IV–V) injuries generally require surgery. There is however, evidence that the clinical situation should be the most important factor in guiding management decisions [8]. Even patients with high-grade splenic injuries may be managed conservatively if they are haemodynamically stable. Conversely, delayed splenic rupture requiring surgery may occur in patients whose initial CT shows low-grade splenic injury [8]. In the case presented, conservative management was initially attempted, but failed as the patient had grade IV splenic injury and became increasingly unstable.

Conclusions

Spontaneous splenic rupture is a rare entity and clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for diagnosis. Abdominal CT scan is often essential to detect this potentially fatal condition, especially if the clinical diagnosis is unclear. Other inflammatory, neoplastic and infectious causes of atraumatic splenic rupture should also be considered. Conservative management is unlikely to succeed in grade IV splenic injury and there should be a low threshold for laparotomy if the patient remains haemodynamically unstable despite resuscitation.

References:

- 1.Al Mashat FM, Sibiany AM, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung KA, Rafaat M. Eruption associated with amoxicillin in a patient with infectious mononucleosis. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:553–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01699_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieberman ME, Levitt MA. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: a case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(1):28–31. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saba HI, Garcia W, Hartmann RC. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: an unusual presenting feature in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. South Med J. 1983;76:247–49. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198302000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma OP. Splenic rupture in sarcoidosis. Report of an unusual case. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;96:101–2. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.96.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foreman BH, Mackler L, Malloy ED. Can we prevent splenic rupture for patients with infectious mononucleosis? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:547–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Looseley A, Hotouras A, Nunes QM, Barlow AP. Atraumatic splenic rupture secondary to infectious mononucleosis: a case report and literature review. Grand Rounds emedicine. 2009 doi: 10.1102/1470-5206.2009.0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker CD, Spring P, Glattli A, Schweizer W. Blunt splenic trauma in adults: can CT findings be used to determine the need for surgery. AJR. 1994;162(2):343–47. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.2.8310923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]