Summary

Background:

We present a case of a lumbar hernia and a review of the literature of this rare hernia type.

Case Report:

The case and the review will discuss the unusual presentations reported, common etiologies, the importance of early operative repair based on the high rate of incarceration and the recent recommendations regarding repair techniques.

Conclusions:

Lumbar hernias are rare cases, but should be pursued in diagnosis and treated aggressively because of the high rate of incarceration. Repair can be accomplished with a minimally invasive technique.

Keywords: lumbar, hernia, Bleichner’s

Background

We present a case of a lumbar hernia with an accompanying review of the literature of this rare type of hernia. The review will discuss unusual presentations, common etiologies, and some of the controversies regarding repair techniques. Lumbar hernias should be treated aggressively because of the high rate of incarceration.

Case Report

Patient history

The patient is a 69 year old male that originally presented with a left sided renal cancer for which he underwent a partial nephrectomy. His past medical history is significant for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, glaucoma and a cerebrovascular accident from which he recovered completely. His family history is significant for lung cancer. The patient never smoked and was an occasional drinker. He has no significant gastrointestinal complaints.

Over an 18 month period, his renal cell cancer metastasized to his lungs and mediastinum. To control his disease chemotherapy was initiated which included Cisplatinum and Gemzar. He developed a malignant pericardial and a left pleural effusion. These were treated with drainage and pleurodesis. He also developed a deep vein thrombosis during treatment and an IVC filter was placed. While being treated with additional chemotherapy, approximately 1 year after the onset of disease, he developed an asymptomatic swelling in his left flank.

Physical exam

The patient is otherwise clinically active, with normal hemodynamics. His pulmonary exam demonstrated reduced breath sounds at the left base, but was clear and normal in expansion on the right. His cardiac exam is normal. His abdominal exam demonstrated normal bowel sounds, no masses or tenderness. Over the period of treatment an enlarging mass could be palpated in the left flank. The mass progressed to be 9 by 7 cm at the lateral border of the left costal margin. The mass was non-tender, and easily reducible. Bowel sounds could be auscultated in the hernia. Imaging demonstrated that when compared to his initial preoperative studies (Figure 1) that over time he had developed a significant left sided lumbar hernia which eventually included bowel contents within the hernia (Figures 2, 3A,B)

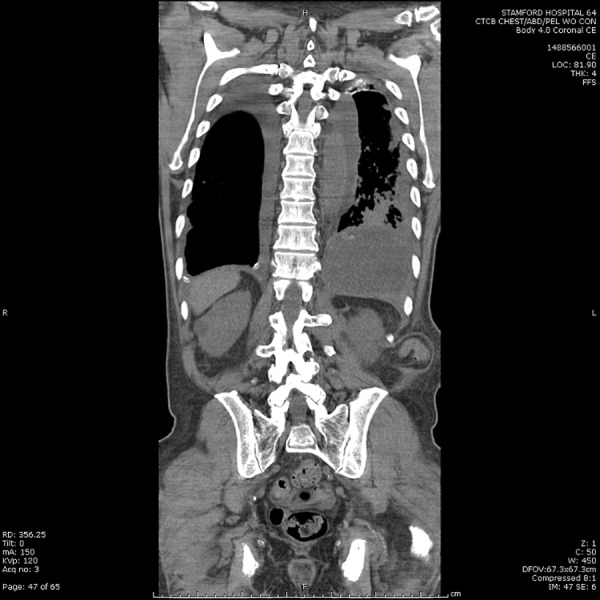

Figure 1.

Base line Computerized Tomography scan prior to operation.

Figure 2.

Interval CT prior to development of a clinically prevalent lumbar hernia.

Figure 3A.

2 years after presentation, progressive presentation of a reducible and asymptomatic Lumbar hernia.

Figure 3B.

2 years after presentation, progressive presentation of a reducible and asymptomatic Lumbar hernia.

Discussion and Review of the Literature

History and anatomy

A Lumbar hernia is the protrusion of intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal contents through a defect of the posterolateral abdominal wall (Figure 4). Barbette was the first, in 1672, to suggest the existence of lumbar hernias. The first case was reported by Garangeot in 1731. Petit and Grynfeltt delineated the boundaries of the inferior and superior lumbar triangles in 1783 and 1866, respectively [1]. These two anatomical sites account for about 95 per cent of lumbar hernias. Loukas et al studied the location and size of lumbar hernias in a human cadaver study. Most hernias were of 5 to 15 cm in surface area in Grynfeltt’s triangle or represented an entire breakdown in the triangle enclosed only by the oblique muscles [2].

Figure 4.

Anatomical description of Lumbar region, illustrating the inferior and superior lumbar triangles and the normal site of a lumbar hernia. Reproduced with permission Behrang Amini under the GNU Free Documentation License Version 1.2.

Etiology

Approximately 20 per cent of lumbar hernias are congenital. During embryologic development, there may be weakening of the area of the aponeuroses of the layered abdominal muscles that derive from somatic mesoderm and may potentially lead to lumbar hernias. Hancock reviewed a series of 33 cases and noted the important association of the hernias with Lumbocostovertebral syndrome [3]. The rest of the lumbar hernias are either primarily or secondarily acquired. The most common cause of primarily acquired lumbar hernias is increased intra-abdominal pressure. Secondarily acquired lumbar hernias are associated with prior surgical incisions, trauma [4], and abscess formation. Diaz et al used fibroblast cell culture techniques from fascial tissue samples from incisional hernia patients. They demonstrated aberrant fibroblast function and caspase –3 activation along with apoptotic signaling all leading to incisional hernia fascia tissue loss [5].

Presentation

Lumbar hernias are often asymptomatic, however they can present as back pain [6,7] abdominal pain [8] or as a gluteal abscess [9]. The rarity of the hernia and the unusual patterns of presentation in addition to the high incidence of asymptomatic cases emphasizes the need for a high index of suspicion.

Incarceration

Incarceration is reported at a high rate for lumbar hernias in the range of 25% [1,11]. Multiple organs have been reported to herniate through lumbar hernias in addition to small intestine, including colon [11,12] and segments of the liver [13].

Repair

The classic repair technique uses the open approach, where closure of the defect is performed primarily by using prosthetic mesh. The laparoscopic approach, either transabdominal or extraperitoneal, is an alternative. Repair of lumbar hernias should be performed as early as possible to avoid incarceration and strangulation [14]. The results from open procedures have been good but multiple reports have emphasized a minimally invasive approach. In an anatomical study, Stumpf defined the anatomy and recommended a retromuscular sublay repair as the standard [15]. The efficacy of this approach was further emphasized in the sutureless “Meshplasty” as described in Garg et al. [16] and Gagner et al. [17] both of whom described a laparoscopic preperitoneal approach. A variation of this technique was reported by Shekarriz et al. [18] and Sharma et al. [19] as a transperitoneal preperitoneal laparoscopic approach which also utilized mesh. Two larger studies involving Lumbar hernia repairs have been reported. Memon et al reported on 200 hernia repairs, some of which were lumbar hernias. They reported a wound infection rate of 6.5% and mortality rate of 0.5% with no recurrences in the first two years [20]. Fei and Li reported on 41 “flank” hernias which were repaired either by an extended sublay mesh or a smaller “routine” sublay mesh using an open technique. The complication rate during a 2 year follow up for the extended mesh group was 28% which included seromas, hematomas and pain. The “routine” mesh group experienced a 13% complication rate. But unlike the extended group which experienced no recurrences, this group experienced a significantly higher recurrence rate at 30%. They recommended the extended mesh approach [21].

Conclusions

Lumbar hernias are rare cases, often difficult to diagnose. These hernias should be part of a differential diagnosis for back and abdominal pain and when identified, treated aggressively because of the high rate of incarceration. Repair can be accomplished with a minimally invasive technique.

References:

- 1.Stamatioui D, Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis LJ, Mirilas P. Lumbar hernia: Surgical anatomy, embrology, and technique of repair. Am Surg. 2009;75:202–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loukas M, El-Zammar D, Shoja MM, et al. The Clinical anatomy of the triangle of Grynfelt. Hernia. 2008;12:227–31. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hancock BJ, Wiseman NE. Incarcerated congenital lumbar hernia associated with lumbocostovertebral syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:782–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiber JR, Cushman JG. Traumatic lumbar visceral hernia. J Emerg Med. 2011;18 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.047. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz R, Quiles MT, Guillem-Marti J, et al. Apoptosis-like cell death induction and aberrant fibroblast properties in human incisional hernia fascia. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2641–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lillie GR, Deppert E. Inferior lumbar triangle hernia as a rarely reported cause o low back pain: a report of 4 cases. J Chiropr Med. 2010;9:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teiblum SS, Hiorne FP, Bisgaard T. Lumbar Hernia. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:968–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cesar D, Valadeo M, Murrahe RJ. Grynflet hernia: case report and literature review. Hernia. 2010;5 doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0722-8. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zub A, Kozka M. Petit’s triangle hernia clinically mimicking gluteal abscess. Przegl Lek. 60(Suppl.7):86–87. 203; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer J. Lumbar hernia incarceration. Zentralbl Chir. 1954;79:1216–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hide IG, Pike EE, Uberoi R. Lumbar Hernia: a rare cause of large bowl obstruction. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:231–32. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.882.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astarcioglu H, Sokmen S, Atila K, Karademir S. Incarcerated inferior lumbar (Petit’s) hernia. Hernia. 2003;7:158–60. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salemis NS, Nisotakis k, Gourgiotis S, Tsohataridis E. Segmental liver incarceration through a recurrent incisional lumbar hernia. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:442–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakarya A, Aydede H, Erhan MY, et al. Laparoscopic repair of acquired lumbar hernia. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1494. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-4202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stumpf M, Conze J, Prescher A, et al. The lateral incisional hernia: anatomical considerations for a standardized retromuscular sublay repair. Hernia. 2009;13:293–97. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg CP, Sharma P, Patel G, Malik P. Sutureless meshplasty in lumbar hernia. Surg Innov. 2011;18(3):285–88. doi: 10.1177/1553350610397214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gagner M, Milone L, Gumbs A, Turner P. laparoscopic repair of left lumbar hernia after laparoscopic left nephrectomy. JSLS. 2010;14:405–9. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12924466007322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shekarriz B, Graziottin TM, Gholami S, et al. Transperitoneal preperitoneal laparoscopic lumbar incisional herniorrhaphy. J Urol. 2001;166:1267–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma A, Panse R, Khullar R, et al. Laparoscopic transabdominal extraperitoneal repair of lumbar hernia. J Minim Access Surg. 2005;1:70–73. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.16530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memon MR, Shaikh AA, Memon SR, Jamro B. Results of Stoppa’s sublay mesh repair in incisional and ventral hernias. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:798–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fei Y, Li L. Comparison of two repairing procedures for abdominal wall reconstruction in patients with flank hernia. Zhonggou Xiu Fu Chong Jain Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;24:1506–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]