Abstract

Gingival hyperplasia is a rare condition but it is important for cosmetic and mechanic reasons and because of its potential as an indicator of systemic disease. Gingival fibromatosis may exist as an isolated abnormality or as part of a syndrome. In this article a case that was diagnosed clinically and histologically as idiopathic gingival fibromatosis is presented. Patient with gingival hyperplasia should be examined to exclude other reasons to determine the idiopathic gingival fibromatosis or not. Treatment is not required in all cases of idiopathic gingival hyperplasia. Surgical excision is indicated if mechanical problems exist. Recurrence has not been reported.

Keywords: gingival, hyperplasia, fibromatosis

INTRODUCTION

Gingival hyperplasia is a rare condition but it is important for cosmetic and mechanic reasons or possibility of a part of a systemic disease. In some pathological conditions, gingivitis caused by plaque accumulation can be more severe. In puberty and pregnancy, hyperplasia of the gingival tissues may be due to poor oral hygiene, inadequate nutrition, or systemic hormonal stimulation (1, 2). Gingival enlargements are also seen in several blood dyscrasias e.g. leukaemia, thrombocytopenia, or thrombocytopathy (3). Other etyologic factors are listed in Table 1. A progressive fibrous enlargement of the gingiva is a feature of idiopathic fibrous hyperplasia of the gingiva. Characteristically, this massive enlargement appears to cover the tooth surfaces. While the cause of the disease is unknown, there appears to be a genetic predisposition (4, 5). Gingival fibromatosis may exist as an isolated abnormality or as part of a syndrome (6, 7). Table 2 gives an overview of syndrome related gingival overgrowth. In this article, a 12 year girl who applied to pediatric service with the gingival hyperplasia is presented.

Table 1.

Causes of gingival hyperplasia

| Visuals aspect | Cause |

|---|---|

| Gingivitis | Bacterial plaque |

| More severe gingivitis diabetes | Bacterial plaque and uncontrolled |

| Puberty or pregnancy epulides | Bacterial plaque and puberty or pregnancy |

| Drug-induced gingival over-growth phenytoin, Dilantin | Bacterial plaque and medicine |

| Enlarged, oedematous, soft and tender, easily bleeding gingivitis | Leukaemia |

| Gingival enlargement and spontaneous bleeding | Thrombocytopenia and thrombocytopathy |

| Part of a syndrome | See Table 2 |

Table 2.

An overview of gingival overgrowth related with a syndrome

| Syndrome | Symptoms other than gingival overgrowth | Heredity |

|---|---|---|

| Rutherfurd Syndrome | Corneal dystrophy | Dominant |

| Cross Syndrome | Microphthalmia, mental retardation, pigmentary defects | Recessive |

| Ramon Syndrome | Hypertrichosis, mental retardation, delayed development epilepsy, cherubism | Recessive |

| Laband Syndrome | Syndactily, nose and ear abnormalities, hyperplasia of the nails and terminal phalanges | Dominant |

CASE REPORT

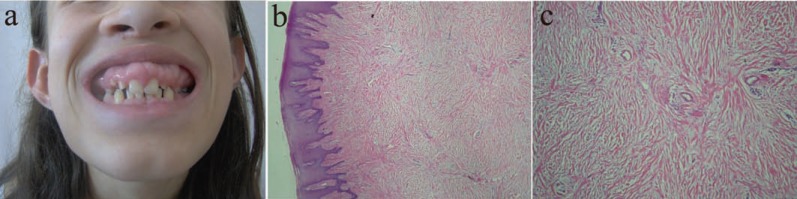

Patient has had gingival problems for 5 years. There were no any systemic diseases and drug using reported. In intraoral examination, the hyperplastic gingiva covered the teeth. Especially at the palatinal region this hyperplasia covered the palatinal dome and the tongue movements were restricted and speech trouble was seen. The gingival hyperplasia presented with colour. Complete blood cell count and chemistry tests, urinary and blood aminoacids, mucopolysccarides and hormonal profiles were normal. With the clinical and the histopathological examinations, the case was diagnoised as idiopatic gingival fibromatosis which was characteristed by fibrous gingival hyperplasia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

Gingival fibromatosis may exist as an isolated abnormality or as part of a syndrome (6, 7). As an isolated finding, it is mostly sporadic, but an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern is also possible. Rarely, autosomal recessive inheritance is found.

Patients with gingival hyperplasia should be examined carefully and blood samples sould be taken to exclude blood dyscrasias (3). While the gingiva may be the only tissue involved, some cases display gingival fibromatosis in association with hypertrichosis, and/or mental retardation, and/or epilepsy. The association of gingival fibromatosis and corneal dystrophy is recognized as an autosomal dominant trait known as the Rutherfurd syndrome (6). Cross syndrome is, almost certainly, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by gingival fibromatosis, microphthalmia, mental retardation, and pigmentary defects (7). Ramon syndrome is another, probably autosomal recessive, condition involving gingival fibromatosis, as well as hypertrichosis, mental retardation, delayed development, epilepsy and cherubism (8). Laband syndrome features gingival fibromatosis, syndactily, nose and ear abnormalities, and hypoplasia of the nails and terminal phalanges.

After excluding other reasons of gingival hyperplasia it is named as idiopathic gingival hyperplasia. Treatment is not required in all cases of idiopathic gingival hyperplasia. Surgical excision is indicated if mechanical problems exist (9). Recurrence has not been reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Katsikeris N, Angelopoulos E, Angelopoulos AP. Peripheral giant cell granuloma: clinicopathological study of 224 new cases and review of 95 reported cases. Int. J. Oral. and Maxillofac. Surg. 1988;17(2):94–99. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(88)80158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood NK, Goaz PW. Differential Diagnosis of Oral Lesions. 4th. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1991. p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell CC, Weir DM, James VS, Cartwright KAV, et al. The Stonehouse study: secretor status and carriage of Neisseria species. Epidemiol. Infect. 1989;120:1–10. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800029629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salinas CF. Orodental findings and genetic disorders. Birth Defects. 1982;18:79–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro SD, Jorgenson RJ. Heterogeneity in genetic disorders that affect the orifices. Birth Defects. 1983;19(1):155–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldred MJ, Bartold PM. Genetic disorders of the gingivae and periodontium. Periodontol. 2000;18:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Levin LS. Syndromes of the Head and Neck. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pina Neto JM, Moreno AF, Silva LR, Velludo MA, et al. Cherubism, gingival fibromatosis, epilepsy, and mental deficiency (Ramon syndrome) with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Med. Gen. 1986;25:433–441. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roshkind DM. The practical use of lasers in general practice. Alpha Omegan. 2008 Sep;101(3):152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.aodf.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]