Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

Voice conversion algorithms may benefit cochlear implant (CI) users who better understand speech produced by one talker than by another. It is unclear how the source or target talker's fundamental frequency (F0) information may contribute to perception of converted speech. This study evaluated voice conversion algorithms for CI users in which the source or target talker's F0 was included in the converted speech.

Study Design

Development and evaluation of computerized voice conversion algorithms in CI patients.

Methods

A series of cepstral-analysis based algorithms were developed and evaluated in six CI users. The algorithms converted talker voice gender (male-to-female, or female-to-male); either the source or target talker F0 was included in the converted speech. The voice conversion algorithms were evaluated in terms of recognition of IEEE sentences, speech quality, and voice gender discrimination.

Results

For both IEEE sentence recognition and voice quality ratings, performance was poorer with the voice conversion algorithms than with original speech. Performance on female-to-male conversion was superior to male-to-female conversion. Voice gender recognition performance showed that listeners strongly cued to the F0 that was included within the converted speech.

Conclusion

Limitations on spectral channel information experienced by CI users may result in poorer performance with voice conversion algorithms due to distortion of speech formant information and degradation of the spectral envelope. The strong cueing to F0 within the voice conversion algorithms suggests that CI users are able to utilize temporal periodicity information for some pitch-related tasks.

INTRODUCTION

Given the limited spectral resolution provided by cochlear implants (CIs), CI listeners must attend to temporally coded fundamental frequency (F0) cues for pitch-related speech perception (1-4). Additionally, CI users often report differences in voice quality and/or speech understanding across gender and talkers. Optimizing the acoustic input through voice conversion might improve performance for CI users who are sensitive to talker differences. In voice conversion, speech produced by a source talker is modified to sound as if produced by a target talker (5-19). Because CI users may better understand or prefer speech produced by a particular gender or talker, voice conversion may benefit CI users by optimizing the acoustic input according to their preferred gender or talker profile, potentially allowing for improved speech comprehension (20-21).

In the source-filter model of speech production, acoustic output is modeled as an excitation (from the larynx) that undergoes filtering by the vocal tract superior to the larynx. A number of modeling methods have been used historically in modeling for speech analysis and synthesis (Appendix 1). Cepstral analysis is one such technique. Cepstral analysis allows the excitation information in a speech signal to be separated from the vocal tract transfer function, which is represented in the spectral envelope (20). The coefficients of the spectral envelope peaks are represented by Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs). The Mel scale, a nonlinear frequency scale, allows emphasis of the lower range of frequencies to which the human ear is more sensitive. To transform speech from a source to a target talker, a transformation function Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) is created for the source and target talker speech. The parameters of the transformation function GMM are estimated during training (10,15,23,24).

Although GMM based voice conversion provides high accuracy, the result voice quality is degraded. On the other hand, Vocal Tract Length Normalization (VTLN) (16) and Dynamic Frequency Warping (DFW) (25) methods enable direct modification of formant positions along the frequency axis and provide a high quality of converted voice. However, this occurs at a cost of degraded conversion accuracy. A combination of the two methods of GMM transformation and frequency warping provides better quality and accuracy. (10)

Kawahara (24) originally described the STRAIGHT software algorithm, which employs a high quality parametric representation of the voice transformation in which not only formant peak locations, but also F0 may be manipulated independently. This allows for changes in formant location to be combined with either the source or target F0 and provides a flexible processing approach. Because formant and F0 cues can be independently varied, using the STRAIGHT algorithm allows estimation of the contributions of the spectral envelope and voice pitch to different measures of speech perception. Moreover, using parameters generated from the STRAIGHT software enables generation of higher quality converted voice (17).

In this study, experimental VTLN-based voice conversion algorithms were evaluated in CI users. Speech was transformed from a male to a female talker, and vice-versa. Three transformation functions (Full, G, and Ratio) were applied to voice conversion algorithms; the transformation functions differed in terms of weighting of the spectral envelope and in terms of computational complexity. To evaluate the contribution of voice pitch to converted speech, the source talker F0 or target talker F0 was combined with the transformed spectral envelope. We hypothesized that CI users would be sensitive to temporal pitch cues, even when paired with a transformed spectral envelope, due to the limited spectral resolution of the implant device.

METHODS

Subjects

Six adult, post-lingually deafened CI users participated in the experiment. All subjects were reimbursed for their time and expenses, and all provided informed consent prior to participation in accordance with the local institutional review board (IRB). Subjects were tested using their clinical processors and settings. Subjects were asked to not change these settings during testing. Subject demographics are shown in Table I.

Table I.

CI subject demographics. The “self-reported gender bias” refers to the talker gender with which subjects reported better speech performance in everyday listening conditions.

| Subject | Gender | Etiology | Age at testing (years) | CI experience (years) | Device, strategy | Self-reported gender bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | F | Ototoxic drugs | 63 | 11 (L) 7 (R) |

N-24, ACE N-24, ACE |

F |

| S2 | F | Unknown | 47 | 3 | Freedom, ACE | F |

| S3 | M | Noise exposure | 79 | 15 | N-22, SPEAK | F |

| S4 | M | Unknown | 58 | 16 (L) 2 (R) |

N-22, SPEAK Freedom, ACE |

M |

| S5 | F | Genetic | 66 | 6 | N-24, ACE | M |

| S6 | F | Otosclerosis | 76 | 21 | N-22, SPEAK | F |

N-24 = Nucleus 24, ACE = Advanced combination encoder, SPEAK = Spectral peak encoder.

Voice conversion algorithms

In the VTLN method, the frequency axis of the source talker is modified in order to shift the vocal tract along the frequency axis to match that of the target talker. This changes formant positions to match the target. This modification alone, however, is not sufficient to produce optimal voice conversion. Therefore, the spectral envelope amplitude is further transformed after applying VTLN using another transformation function. In this study, three transformation functions (Full, G and Ratio), in which the spectral envelope was differently weighted, were combined with the VTLN. The source talker F0 or target talker F0 was included in the transformation function.

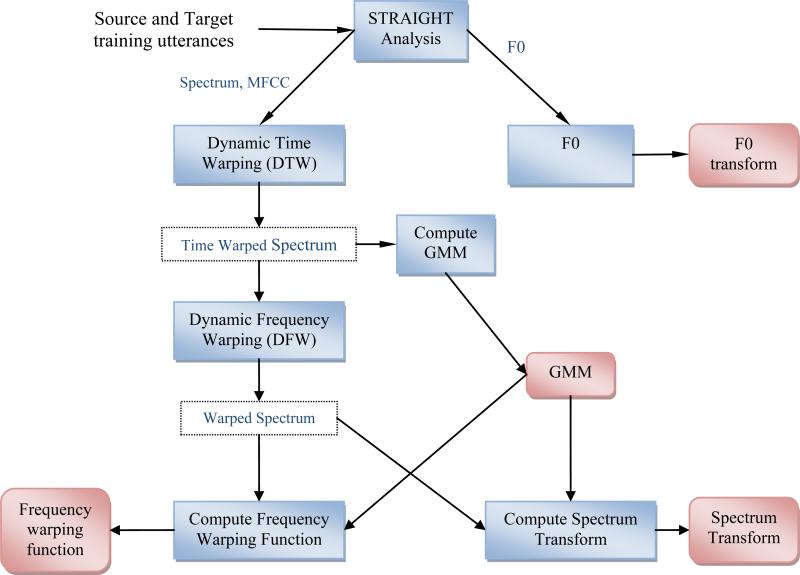

Figure 1 illustrates the training phase common to all three VTLN spectrum transform algorithms. In the training phase, a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) and a F0 transformation were designed using the STRAIGHT software. A number of control points were defined along the frequency axis. By modifying the positions of these control points, a piecewise linear function for modifying the frequency axis was computed; the spectrum obtained from STRAIGHT was shifted along the frequency axis according to this function. During training, the shift of each control point was estimated by the GMM. First, “dynamic time warping” (DTW) was performed to align the frames of the source and target talker in the time domain. Next, “dynamic frequency warping” (DFW) was performed to align each frame of the target and source talker along the frequency axis (17,18). Using the GMM along with the warped frequency spectrum, a frequency transformation function was developed. After applying the frequency transformation function, the source formants were similar to those of the target talker.

Figure 1.

Training Phase of the Voice Conversion system. STRAIGHT parameters are computed from training speech files. MFCC coefficients are computed from STRAIGHT spectrum and are used to compute GMM and to align the training and target utterances using DTW. The aligned frames are then used to create transformation functions. The outputs of the training are represented by rounded rectangles. The Spectrum transform has 3 options: Full, G, or Ratio-based transform. On the upper branch, a transformation for F0 is computed.

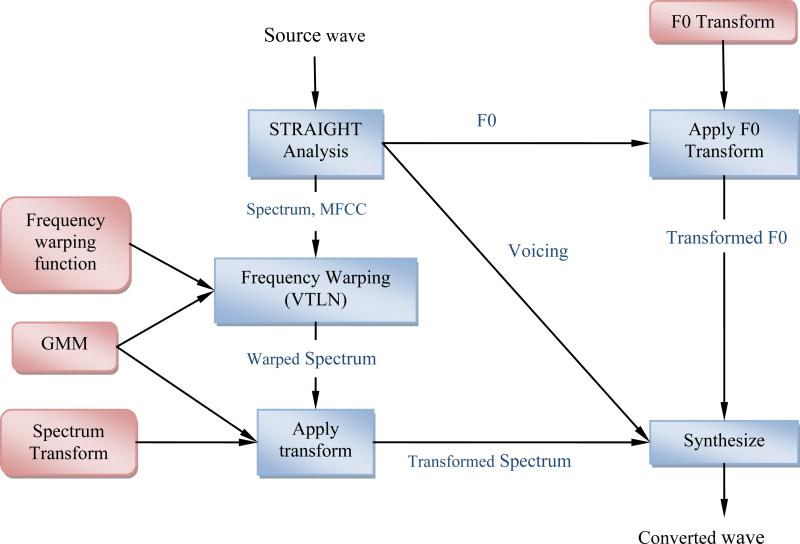

To improve speech quality after applying VTLN, the spectral envelope was modified using one of the three transforms (Figure 2): Full, G, and Ratio. The three transforms are described in greater detail below.

Figure 2.

Voice Conversion. Voice conversion is performed by first applying VTLN to compute the frequency-warped spectrum, and then by modifying spectral envelope according to the selected transformation function (Full, G, or Ratio). The rounded rectangles represent the parameters learned from the training phase.

In the Full Transform, the output spectrum from VTLN is further transformed using the function described in (15). The training data are first aligned in time and frequency, and the aligned data are then used to compute the transformation function. The function for transforming frame xt (after applying VTLN) to get frame yt is described as follows (Equations 1 and 2):

| (1) |

and

| (2) |

where m is the number of Gaussian mixtures, μi is the mean of the ith Gaussian mixture, Σi is the variance of the ith Gaussian mixture, νi and Γi are parameters of the transformation function related to the ith mixture, αi is the weight of the ith mixture, and N(xt; μi, Σi) is the Gaussian function of the ith Gaussian mixture. Γi is a matrix having the same size as Σi , and νi is a vector having the same size as μi and the feature vector. These parameters are estimated during training. Note that this transformation function is applied in the MFCC domain. The MFCCs are computed from the frequency warped STRAIGHT spectrum, and the transformed MFCCs are then used to shape the spectrum according to the smooth spectral envelope obtained from the MFCCs.

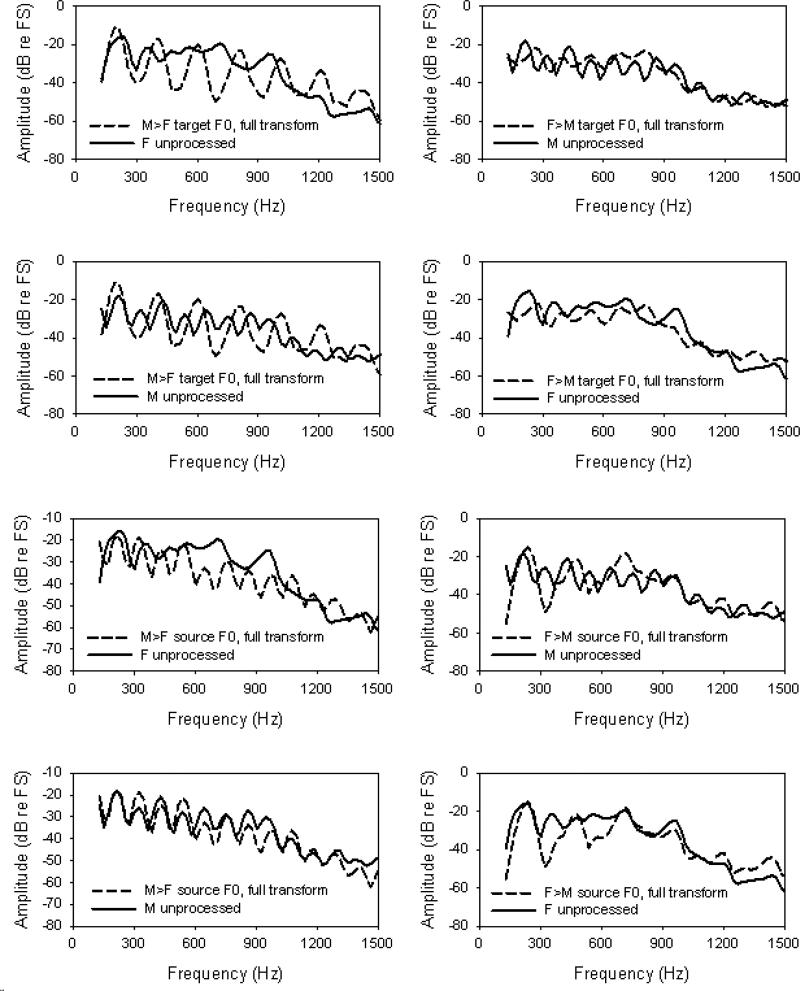

Figure 3 shows spectral envelopes for the vowel /o/ after the Full transformation (dashed lines); for comparison, unprocessed spectral envelopes are shown for the male and female talkers (solid lines). For the male-to-female transforms (left column of Fig. 3), lower formant information (<600 Hz) was shifted within range of the female target. For the female-to-male transforms (right column of Fig. 3), the shifting of lower formant information was less accurate. Whether from the source or target talker, F0 strongly contributed to the transformed output. The male-to-female transform with the source F0 (lower left corner of Fig. 3) provides a strong example of the contribution of F0 to the transformed speech.

Figure 3.

Spectral envelopes for the vowel /o/. The left panel shows male-to-female (M→F) conversion and the right panel shows female-to-male (F→M) conversions; all conversions were performed using the Full transform. The top 4 panels show conversions that included the target talker F0 and the bottom 4 panels show conversions that included to source talker F0. In each panel, the dashed line shows the converted speech and the solid line shows unprocessed speech from the male or female talker.

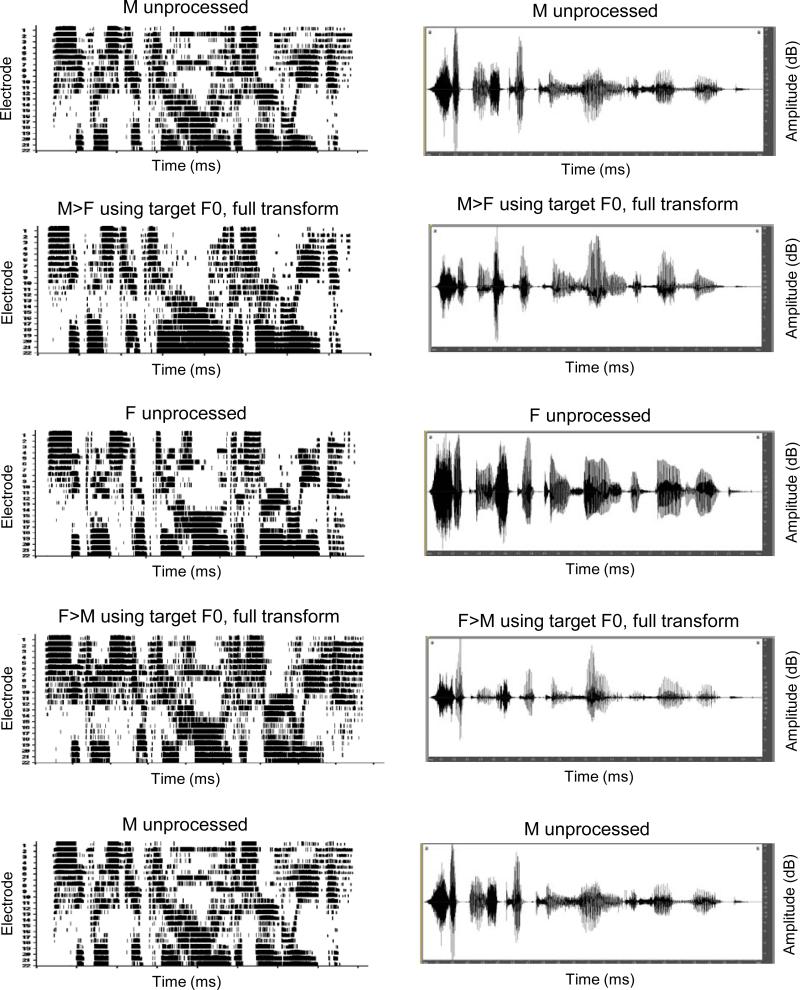

Figure 4 shows electrodograms (right column) and waveforms (left column) for the test sentence “Sickness kept him home the third week.” The electrodograms show the electrode stimulation pattern over time for standard clinical CI processing with the Nucleus-24 device. Electrodograms are similar to spectrograms, except modified to include stimulation CI parameters (especially the acoustic frequency-to-electrode allocation). Note that for different CI devices (or even for different stimulation parameters within a given device), the stimulation patterns would be somewhat different. However, the relative differences would be expected to be similar as shown in Figure 4. The default frequency allocation (Table 6; input frequency range = 188-7930 Hz) and stimulation rate (900 pulses per second per electrode) were used to generate the electrodograms. For the male-to-female transform (second panel from the top), the electrodogram shows a mixture of the source (male – top panel) and target stimulation patterns (female – third panel from the top). Similarly, the female-to-male transform (fourth panel from the top), the electrodogram shows a mixture of the source (female – third panel from the top) and target stimulation patterns (male – bottom panel). Although not as strong as the contrast between the unprocessed male (top panel) and female talkers (third panel from the top), there are differences in the stimulation patterns between the female-to-male (fourth panel from the top) and male-to-female transformed talkers (second panel from the top), especially for the basal electrodes (i.e., frequency information above 1500 Hz). Similarly, the waveforms (right column) show that the transformed speech exhibited a mixture of the amplitude contours of the source and target talkers.

Figure 4.

Electrodograms (left column) and waveforms (right column) for the sentence “Sickness kept him home the third week.” The top and bottom panels show unprocessed speech produced by the male talker (the panels are identical), and the third panel from the top shows unprocessed speech produced by the female talker. The second panel from the top shows an example of the male-to-female (M→F) conversion using the Full transform and including the target talker F0. The fourth panel from the top shows an example of female-to-male (F→M) conversion using the Full transform and including the target talker F0. The electrodograms were generated using RF Statistics software (Cooperative Research Centre for Cochlear Implant and Hearing Aid Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). The electrodograms were generated using the default stimulation parameters for the Nucleus Freedom device (i.e., Table 6 frequency allocation, 900 pulses/second/electrode, 22 active electrodes). The y-axis of the electrodograms shows the electrode number, from 22 (most apical) to 1 (most basal); the x-axis shows time. The y-axis of the waveforms shows amplitude (dB re full scale, or FS); the x-axis shows time.

The G Transform requires less computational load than the Full Transform. In the G Transform, only one matrix is computed to transform the source into the target spectrum, with the additive term discarded (see Equation 3). This reduces noise in the transformed speech by removing the additive terms μi and νi from Equation 1.

| (3) |

In the Ratio Transform, transformed formant amplitudes are modified according to the average ratio between the target and source spectrum. During training, the ratio is taken as a weighted average for each mixture of the GMM. To perform the voice conversion, the weighted average of the ratios of all mixtures is taken for each spectrum sample. The ratios are applied after aligning the spectrum frequency axis. The Ratio Transform is simpler due to the smaller number of parameters (see Equation 4).

| (4) |

where ri : is the ratio vector for the ith mixture. Note that this transformation function is applied directly on the frequency warped STRAIGHT spectrum, and not in the MFCC domain.

Procedures

Sentence recognition was measured in quiet using IEEE (1969) sentences. The IEEE database included 720 sentences (divided into 72 lists of ten sentences each) produced by one male and one female talker. The mean F0 (across all sentences) was 110.78 Hz for the male talker and 187.98 Hz for the female talker. Voice conversion was performed from the female to male talker (F→M) or from the male to female talker (M→F) using the Full, G and Ratio Transforms described above; the target F0 or source F0 was included in the conversion. All stimuli were normalized to have the same long-term root-mean square (RMS) presentation level (65 dB). Each test condition was evaluated using three sentence lists. During testing, a sentence was randomly selected (without replacement) from the test list and presented to the subject in sound field via audio interface (Edirol UA-25, Roland, Los Angeles, CA) connected to an amplifier (Crown D-75A, Crown, Elkhart, IN) and a single loudspeaker (Tannoy Reveal, Tannoy Corporation, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada). The subject repeated the sentence as accurately as possible and the experimenter scored word-in-sentence recognition. The test order of the experimental conditions was randomized within and across subjects.

After measuring sentence recognition, speech quality ratings were obtained for each algorithm on a scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent), referenced to ideal speech from an ideal talker, similar to the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) used by Toda (18).

Voice gender identification was measured using 140 sentences processed by the different VTLN algorithms, for both conversion directions, and included either the source or target F0. The stimulus set included 10 sentences for each test condition, including the unprocessed speech. Voice gender discrimination was measured to assess whether F0 cues dominated the voice gender percept, even when paired with an opposite transform in talker spectrum. Subjects were asked to identify the whether the talker was male or female. The correctness of response was evaluated according to the included F0. The percent correct was calculated for each test condition. Conditions were randomized within each test block.

RESULTS

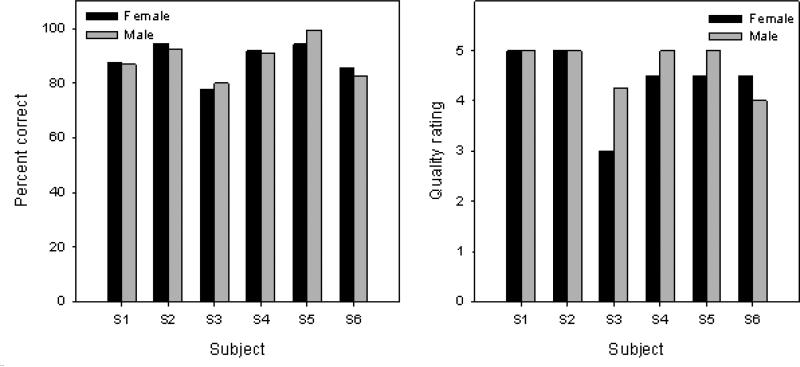

Figure 5 shows individual subjects’ sentence recognition scores (left panel) and voice quality ratings (right panel) with the unprocessed female (black bars) and male (gray bars) talkers. Although overall sentence recognition performance varied across subjects, a one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RM ANOVA) showed no significant effect of talker [F(1,5)=0.024, p=0.881]. Although some subjects seemed to rate one talker higher than another, a one-way RM ANOVA showed no significant effect of talker [F(1,5)=1.416, p=0.287].

Figure 5.

Individual CI subjects’ IEEE sentence recognition (left panel) and voice quality ratings (right panel) with the unprocessed female (black bars) and male (gray bars).

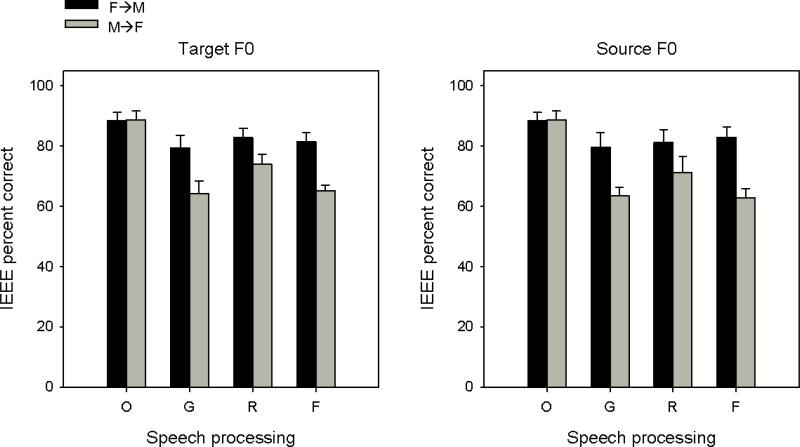

Figure 6 shows mean IEEE sentence recognition scores for the original speech and each of the experimental algorithms, with the target F0 or source F0 included in the conversion. Table II shows the results of a three-way RM ANOVA, with algorithm (Original, Full, G, Ratio), direction of conversion (F→M, M→F) and voice pitch (target F0 or source F0) as factors. Performance was significantly affected by the algorithm (p=0.002) and direction of conversion (p=0.001), but not by voice pitch. Because there was no effect of voice pitch, data was collapsed across the target and source F0 conditions, and an additional two-way RM ANOVA was performed with algorithm and direction of conversion as factors; the results are shown in Table III. Performance was significantly affected by algorithm (p<0.001) and direction (p=0.001), and there was a significant interaction (p<0.001). Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that performance with the original speech was significantly better than with any of the VTLN algorithms (p<0.05), and that performance with the F→M conversion was better than with the M→F conversion (p<0.05). Post-hoc comparisons also showed a greater number of significant differences between algorithms for the M→F conversion than for the F→M conversion.

Figure 6.

Mean IEEE sentence recognition scores as a function of the VTLN algorithm when the target (left panel) or source F0 (right panel) was included in the transformed speech. The black bars show the female-to-male conversions and the gray bars show the male-to-female conversions. The error bars show the standard error. O = Original speech, G = G transform, R = Ratio transform, F = Full transform

Table II.

Results of three-way RM ANOVA.

| IEEE sentences | Quality rating | Voice gender | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | dF, res | F-ratio | p-value | dF, res | F-ratio | p-value | dF, res | F-ratio | p-value |

| Algorithm (Original, Full, G, Ratio) | 3, 15 | 77.55 | 0.002 | 3, 15 | 10.56 | 0.042 | 3, 15 | 6.95 | 0.004 |

| Direction (F→M, M→F) | 1, 15 | 46.47 | 0.001 | 1, 15 | 38.16 | 0.002 | 1, 15 | 0.00 | 0.998 |

| F0 (Target, Source) | 1, 15 | 0.62 | 0.466 | 1, 15 | 0.87 | 0.393 | 1, 15 | 5.92 | 0.059 |

| Algorithm × Direction | 3, 15 | 12.66 | 0.033 | 3, 15 | 5.26 | 0.103 | 3, 15 | 1.12 | 0.374 |

| Algorithm × F0 | 3, 15 | 0.20 | 0.894 | 3, 15 | 0.19 | 0.894 | 3, 15 | 4.89 | 0.015 |

| F0 × Direction | 1, 15 | 0.85 | 0.399 | 1, 15 | 0.75 | 0.425 | 1, 15 | 0.62 | 0.468 |

| Algorithm × Direction × F0 | 3, 15 | 0.80 | 0.571 | 3, 15 | 4.79 | 0.115 | 3, 15 | 0.60 | 0.630 |

Significant effects are shown in bold italics. F→M = Female to male conversion, M→F = Male to female conversion, F0 = Included voice pitch.

Table III.

Results of 2-way RM ANOVA.

| Factor | dF, res | F-ratio | p-value | Bonferroni post-hoc (p<0.05) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEEE Sentences | Algorithm (Original, Full, G, Ratio) | 3, 15 | 40.71 | <0.001 |

Original > Full, G, Ratio

Ratio > G |

| Direction (F→M, M→F) | 1, 15 | 46.47 | 0.001 | F→M > M→F | |

| Algorithm × Direction | 3, 15 | 31.07 | <0.001 | F→M: Original > G M→F: Original > Full, G, Ratio; Ratio > Full, G Full, G, Ratio: F→M > M→F |

|

| Quality rating | Algorithm (Original, Full, G, Ratio) | 3, 15 | 20.06 | <0.001 | Original > Full, G, Ratio |

| Direction (F→M, M→F) | 1, 15 | 38.16 | 0.002 | F→M>M→F | |

| Algorithm × Direction | 3, 15 | 9.05 | 0.001 | M→F: Original > Full, G, Ratio Full, G: F→M > M→F |

|

| Voice gender | Algorithm (Original, Full, G, Ratio) | 3, 15 | 6.91 | 0.004 | Original > G, Ratio, Full |

| F0 (Target, Source) | 1, 15 | 5.88 | 0.060 | ||

| Algorithm × F0 | 3, 15 | 4.84 | 0.015 | Source: Original > G, Ratio, Full |

Significant effects are shown in bold italics. F→M = Female to male conversion, M→F = Male to female conversion, F0 = Included voice pitch.

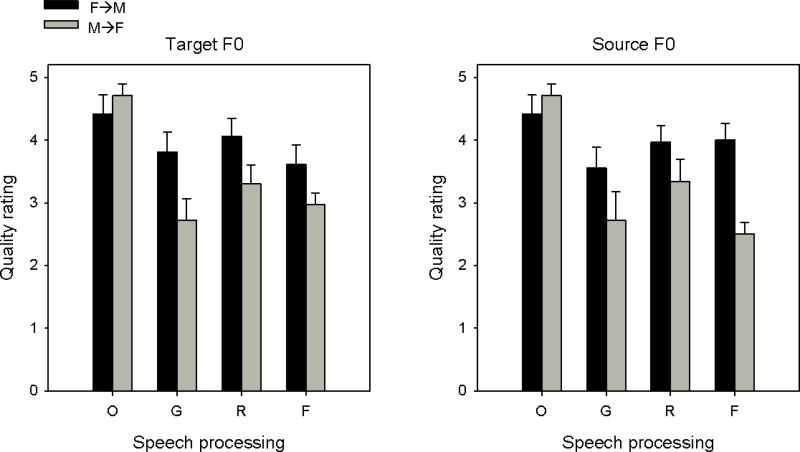

Figure 7 shows mean speech quality ratings for the original speech and each of the experimental algorithms, with the target F0 or source F0 included in the conversion. As shown in Table II, a three-way RM ANOVA showed that speech quality ratings were significantly affected by the algorithm (p=0.042) and direction of conversion (p<0.001), but not by voice pitch (p=0.393). Because there was no effect of voice pitch, data was collapsed across the target and source F0 conditions, and an additional two-way RM ANOVA was performed with algorithm and direction of conversion as factors; the results are shown in Table III. Similar to IEEE sentence recognition, speech quality ratings were significantly affected by algorithm (p<0.001) and direction (p=0.002), and there was a significant interaction (p=0.001). Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that performance with the original speech was significantly better than with the VTLN algorithms (p<0.05), and that performance with the F→M conversion was better than with the M→F conversion (p<0.05). Post-hoc comparisons showed significant differences between algorithms only for the M→F conversion.

Figure 7.

Mean voice quality ratings as a function of the VTLN algorithm when the target (left panel) or source F0 (right panel) was included in the transformed speech. The black bars show the female-to-male conversions and the gray bars show the male-to-female conversions. The error bars show the standard error. O = Original speech, G = G transform, R = Ratio transform, F = Full transform.

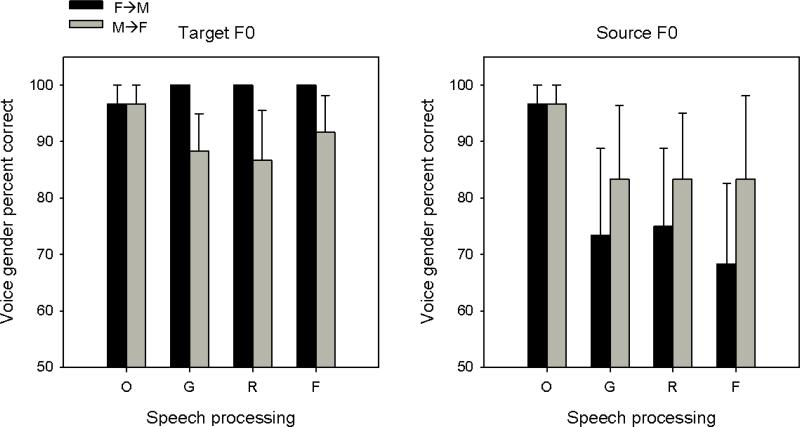

Figure 8 shows mean voice gender identification scores for the original speech and each of the experimental algorithms, with the target or source F0 included in the conversion. Percent correct was evaluated in terms of the conversion direction. As shown in Table II, a three-way RM ANOVA showed that voice gender identification was significantly affected only by the algorithm (p=0.004); there was a significant interaction between algorithm and voice pitch (p=0.015). Because there was no effect of conversion direction, data was collapsed across the F→M and M→F conditions, and an additional two-way RM ANOVA was performed with algorithm and voice pitch as factors; the results are shown in Table III. Post-hoc Bonferroni pair-wise comparisons showed that performance with the original speech was significantly better than with the VTLN algorithms only when the source F0 was included (p<0.05). This suggests that when the spectral envelope and voice pitch information was consistent, subjects reliably identified the gender of the converted speech (especially for the F→M conversions). When the spectral envelope conflicted with the voice pitch information, listeners attended more strongly to the voice pitch information, especially for the F→M conversions.

Figure 8.

Mean voice gender identification scores as a function of the VTLN algorithm when the target (left panel) or source F0 (right panel) was included in the transformed speech. The black bars show the female-to-male conversions and the gray bars show the male-to-female conversions. The error bars show the standard error. O = Original speech, G = G transform, R = R transform, F = Full transform.

DISCUSSION

While most of the CI subjects expressed a gender bias for speech understanding in everyday listening conditions (e.g., “I understand women better, especially in noisy situations”), there was no significant difference in sentence recognition or voice quality rating between the unprocessed male and female talkers used in this study (see Fig. 5). In general, CI users perform very well under optimal, quiet, listening conditions and the present CI performance in quiet was very good with the two unprocessed talkers. At this high level of performance, it may have been difficult to show differences between the two unprocessed talkers. The use of sentence materials, which contain context cues, may have limited the effect of talker differences. Previous studies (26-27) have shown talker variability effects, but for phonemes and monosyllable words, which do not contain context cues. Different test talkers may have produced greater difference in performance. Note that subject S3, who rated quality of the talkers most differently, performed nearly equally well with either talker; note also that overall sentence recognition and quality ratings were poorest for S3.

Performance with the M→F conversion was significantly poorer than that with the F→M conversion (p<0.05). Indeed, the poorer performance with the M→F conversions greatly contributed to the generally poorer performance with the algorithms, relative to the original speech. Post-hoc analyses (see Table III) showed that with the F→M conversion, performance with the original speech was significantly better than the G transform only (p<0.05), and then only for the intelligibility scores; there were no significant difference in quality rating or voice gender identification among the experimental conditions with the F→M conversion (p>0.05). The better performance with the F→M conversion (with the associated down-shifted F0s) may have been due to better access to temporal cues, which would have fallen within CI subjects’ temporal processing limits (~300 Hz). With the M→F conversions, the shifted voice pitch cues may have been beyond CI subjects’ temporal processing limits. Processing artifacts associated with up-shifted formant frequencies may have also reduced performance with the M→F conversions. Differences in temporal processing between CI users have been correlated with for differences in speech performance (28). Interactions between conversion direction and voice pitch were especially strong for voice gender identification, where pitch cues strongly dominated performance.

For voice gender identification, all six subjects scored much better than chance level (50% correct) with the converted speech; subject S2 scored 100% correct. This suggests a strong contribution of spectral envelope cues to gender identification. However, voice pitch cues also contributed strongly, as evidenced by the influence of F0, especially for the F→M conversions. Because of the limited number of spectral channels, CI listeners must rely more strongly on temporal periodicity cues for voice pitch. The gender identification results suggest that most CI subjects largely attended to temporal envelope periodicity cues. The differential effects of the conversion direction on voice pitch suggests that CI subjects may have better perceived the temporal pitch cues for the F→M than for the M→F conversions. Subjects’ response errors tended to be “male.”

Note that this study does not account for individual patient-related factors such as electrode placement and their proximity to healthy neurons. These factors undoubtedly interact with the CI signal processing (e.g., frequency allocation), both of which would interact with the present voice conversion algorithms and test talkers. If patient-related factors been a limiting factor, we would have expected to see more variability in performance across the two unprocessed test talkers. As shown in Figure 5, there was no significant difference in sentence recognition between the two unprocessed talkers. As noted above, the availability of context cues in the sentences may have reduced performance differences with the original talkers. Other studies have shown stronger differences in performance across talkers (29).

“Front-end” voice conversion algorithms ultimately must interact with CI users’ “back-end” (i.e., the pattern of healthy nerve survival and proximity to the implanted electrodes). The electrodograms shown in Figure 4 illustrate the stimulation patterns for different talker conditions. For individual CI subjects, these patterns may have given rise to different percepts. Note however, that the most different patterns (the unprocessed male and female talkers) produced nearly the same sentenced recognition performance. Voice conversion may be more effective for sentence recognition in noise, where differences in the stimulation pattern (e.g., spectral shift) may more strongly affect performance (30). Voice conversion may also be more effective for improving voice quality. As shown in Figure 5, voice quality for the unprocessed talkers was rated differently by some subjects. Interactions between the talker characteristics, CI signal processing, and patient-related factors may have resulted in one talker being more favorably rated than another. Note that none of the voice conversion algorithms were more highly rated than the unprocessed speech, suggesting that there is much room for improvement.

The results of this study show that in CI patients, the majority of gender cueing likely results from temporal envelope pitch cues, despite formant transformation from the source to the talker. This is in agreement with prior studies (1,3,31). The subjects in this study strongly identified the gender according to the included F0 information. With the converted speech, CI subjects may have experienced difficulty perceiving higher formant peaks in the spectral envelope due to the limited spectral resolution. Talker identification includes F0 cues related to voice gender, but also aspects of the vocal tract that are encoded at the higher formants of the spectral envelope (32). Depending on the condition, voice pitch cues in the temporal envelope may have helped to distinguish F0 cues from other formant cues.

Although performance with converted speech was not improved over the original speech, the present study provides insights that may be improve CI signal processing. The ability to independently manipulate F0 and spectral envelope information with algorithms may be able to be applied to other applications, such as tonal language understanding. Previous studies have shown that voice conversion can help identification of Mandarin tones and words (20). Additionally, while this study did not study bimodal users, residual low frequency hearing may be optimally combined with voice conversion algorithms to address differences in voice pitch (preserved by acoustic hearing) and formant frequency information (preserved by electric hearing). Acoustic CI simulations have been previously used to evaluate voice conversion algorithms (19-20). As normal hearing listeners have a normal distribution of healthy neurons (rather than the irregular nerve survival and electrode placement in the real CI case), CI simulations may be helpful for future work in designing and optimizing voice conversion algorithms for CI users.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the CI subjects for their time and support. We thank Justin Aronoff for assistance in generating the electrodograms. This work was supported in part by NIH grant 5R01DC004993

This work was supported by NIH grant 5R01DC004993

Footnotes

No Financial Disclosures

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Fu QJ, Chinchilla S, Galvin JJ. The role of spectral and temporal cues in voice gender discrimination by normal-hearing listeners and cochlear implant users. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2004;5:253–260. doi: 10.1007/s10162-004-4046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green T, Faulkner A, Rosen S. Spectral and temporal cues to pitch in noise-excited vocoder simulations of continuous-interleaved-sampling cochlear implants. J Acoust Soc Am. 2002;112:2155–2164. doi: 10.1121/1.1506688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu QJ, Chinchilla S, Nogaki G, Galvin JJ. Voice gender identification by cochlear implant users: the role of spectral and temporal resolution. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:1711–1718. doi: 10.1121/1.1985024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee M, Peng SC. Processing F0 with cochlear implants: modulation frequency discrimination and speech intonation recognition. Hear Res. 2008;235:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe M, Nakamura S, Shikano K, Kuwabara H. Voice conversion through vector quantization. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP). 1988:655–658. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arslan LM, Talkin D. Voice conversion by codebook mapping of line spectral frequencies and excitation spectrum. 6th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology (EUROSPEECH) 1997:1347–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childers D, Yegnanarayana B, Wu K. Voice conversion: Factors responsible for quality. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 1985:748–751. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Childers DG. Glottal source modeling for voice conversion. Speech Communication. 1995;16:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Childers DG, Wu K, Hicks D, Yegnanarayana B. Voice conversion. Speech Communication. 1989;8:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erro D, Moreno A. Weighted frequency warping for voice conversion. INTERSPEECH 2007-8th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association. Antwerp, Belgium. 2007:1965–1968. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez-Arriola JM, Hsiao YS, Montero JM, Pardo JM, Childers DG. Voice conversion based on parameter transformation. 5th International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (ICSLP) 1998:987–990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kain A, Macon MW. Design and evaluation of a voice conversion algorithm based on spectral envelope mapping and residual prediction. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2001:813–816. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mashimo M, Toda T, Shikano K, Campbell N. Evaluation of cross-language voice conversion based on GMM and STRAIGHT. 7th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology (EUROSPEECH) 2001:361–364. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtani Y, Toda T, Saruwatari H, Shikano K. Maximum likelihood voice conversion based on GMM with STRAIGHT mixed excitation. ICSLP Ninth International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (INTERSPEECH) 2006:2266–2269. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stylianou Y, Cappé O, Moulines E. Continuous probabilistic transform for voice conversion. IEEE Transactions on Speech and Audio Processing. 1998;6:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suendermann D, Ney H. VTLN-based voice conversion. Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International Symposium on Signal Processing and Information Technology (ISSPIT 2003) 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toda T, Saruwatari H, Shikano K. Voice conversion algorithm based on Gaussian mixture model with dynamic frequency warping of STRAIGHT spectrum. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2001:841–844. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toda T, Saruwatari H, Shikano K. High quality voice conversion based on Gaussian mixture model with dynamic frequency warping. 7th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology (EUROSPEECH) 2001:349–352. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turk O. New methods for voice conversion Electrical and Electronics Engineering. Boğaziçi University. Bogazici University; Istanbul, Turkey: 2003. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo X, Fu QJ. Speaker normalization for chinese vowel recognition in cochlear implants. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52:1358–61. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.847530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C, Galvin JJ, Fu QJ, Narayanan SS. Effect of spectral normalization on different talker speech recognition by cochlear implant users. J Acoust Soc Am. 2008;123:2836–47. doi: 10.1121/1.2897047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis S, Mermelstein P. Comparison of parametric representations for monosyllabic word recognition in continuously spoken sentences. EEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing. 1980;28:357–366. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao X, Milner B. Pitch prediction from MFCC vectors for speech reconstruction. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2004:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawahara H. Speech representation and transformation using adaptive interpolation of weighted spectrum: vocoder revisited. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP). Munich, Germany. 1997:1303–1306. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valbret H, Moulines E, Tubach J. Voice transformation using PSOLA technique. Speech Communication. 1992;11:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullennix JW, Pisoni DB. Stimulus variability and processing dependencies in speech perception. Perception and Psychophysics. 1990;47:379–390. doi: 10.3758/bf03210878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang YP, Fu QJ. Effects of talker variability on vowel recognition in cochlear implants. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49:1331–41. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/095). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu QJ. Temporal processing and speech recognition in cochlear implant users. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1635. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200209160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cullington HE, Zeng FG. Comparison of bimodal and bilateral cochlear implant users on speech recognition with competing talker, music perception, affective prosody discrimination, and talker identification. Ear Hear. 2011;32:16–30. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181edfbd2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li T, Fu QJ. Effects of spectral shifting on speech perception in noise. Hear Res. 2010;270:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burns EM, Viemeister NF. Nonspectral pitch. J Acoust Soc Am. 1976;60:863. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vongphoe M, Zeng FG. Speaker recognition with temporal cues in acoustic and electric hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118:1055–1061. doi: 10.1121/1.1944507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]