SUMMARY

Crosstalk between H2B ubiquitylation (H2Bub) and H3 K4 methylation plays important roles in coordinating functions of diverse cofactors during transcription activation. The underlying mechanism for this trans-tail signaling pathway is poorly defined in higher eukaryotes. Here, we show that 1) ASH2L in the MLL complex is essential for H2Bub-dependent H3 K4 methylation. Deleting or mutating K99 of the N-terminal winged helix (WH) motif in ASH2L abrogates H2Bub-dependent regulation; 2) crosstalk can occur in trans and does not require ubiquitin to be on nucleosomes or histones to exert regulatory effects; 3) Trans-regulation by ubiquitin promotes MLL activity for all three methylation states; and 4) MLL3, an MLL homolog, does not respond to H2Bub, highlighting regulatory specificity for MLL family histone methyltransferases. Altogether, our results potentially expand the classic histone crosstalk to nonhistone proteins, which broadens the scope of chromatin regulation by ubiquitylation signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Ubiquitylation plays a central role in regulating important cellular processes by competing or cooperating with other post-translational modifications. It has been shown that histone ubiquitylation, mostly on histone H2B and H2A, is intimately involved in regulating eukaryotic gene expression by altering chromatin structures (Fierz et al., 2011), controlling accessibility of the transcription machinery (Fleming et al., 2008; Xin et al., 2009), as well as serving as the prerequisite modification for other histone modification events (Laribee et al., 2007; Osley, 2004; Weake and Workman, 2008). The latter function of histone ubiquitylation is often referred to as a classic example of histone crosstalk, which was first reported for yeast H2B K123 ubiquitylation (yH2BK123ub, H2BK120ub in mammal) dependent histone H3 K4 and K79 methylation (Briggs et al., 2002; Ng et al., 2002; Sun and Allis, 2002). The function of this crosstalk in transcription regulation is well established in yeast: yH2BK123ub by Rad6/Bre1 (Hwang et al., 2003; Robzyk et al., 2000) functions to place H3 K4 methylation mark at active gene promoters and, together with the PAF complex, to establish a critical platform to facilitate transition of transcription machinery from initiation to elongation (Hammond-Martel et al., 2012). H2BK120ub also regulates H3 K79 methylation to maintain dynamic chromatin structures at transcribed regions (Fierz et al., 2011) and to facilitate reassembly of nucleosomes in the wake of Pol II passage with the help of histone chaperons (Fleming et al., 2008; Xiao et al., 2005). In addition to transcription regulation, a recent study shows that yH2BK123ub by Rad6/Bre1 and its upstream signaling pathway are able to regulate activity of yeast SET1 (ySET1) towards a kinetochore protein Dam1, extending the role of histone ubiquitylation to regulate yeast mitosis through nonhistone methylation (Latham et al., 2011). H2Bub dependent regulation of H3K4/K79 methylation is evolutionarily conserved. Crosstalk between H2BK120ub and H3K4/K79 methylation is well documented in higher eukaryotes (Kim et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2005). In fact, as a testament for the importance of the ubiquitylation-methylation crosstalk, mutation or mis-regulation of enzymes involved in this regulatory pathway including histone E3 ubiquitin ligase, H3 K4/K79 methyltransferases as well as enzymes catalyzing the reverse reactions is a recurring theme in human malignancies (Chaudhary et al., 2007; Dou and Hess, 2008; Morin et al., 2011; Shekhar et al., 2002). Therefore, understanding the mechanism of histone crosstalk is of vital importance.

Extensive genetic studies have been carried out to understand trans-regulation of H3 K4 and K79 methylation in yeast (Hammond-Martel et al., 2012; Latham and Dent, 2007). These studies point to the importance of Swd2, a component of both the ySET1 and the cleavage and polyadenylation factor (CPF) complexes, in H2Bub mediated trans-regulation (Lee et al., 2007b; Vitaliano-Prunier et al., 2008). It is shown that Rad6/Bre1 mediated yH2BK123ub or Swd2 ubiquitylation regulates Swd2-dependent assembly of the ySET1 complex, which in turn affects H3 K4 methylation. Swd2 is also important for chromatin association of H3 K79 methyltransferase yDOT1L (Lee et al., 2007b). Furthermore, it is proposed that yH2BK123ub serves to increase processivity for both histone methyltransferases, resulting in higher di- and tri-methylation of H3K4/K79 methylation in vivo (Lee et al., 2007b; Shahbazian et al., 2005). However, mechanism for H2Bub dependent DOT1L regulation is later challenged by in vitro biochemical studies (McGinty et al., 2008). It is clearly demonstrated that chemically ubiquitylated H2B K120 is able to directly enhance activity of DOT1L for H3K79me1 and H3K79me2 without auxiliary factors and does not affect DOT1L affinity to nucleosomes (McGinty et al., 2008). Furthermore, this regulation is strictly intra-nucleosomal and is sensitive to the distance between ubiquitin and the nucleosome surface (Chatterjee et al., 2010). These studies, together with the finding that H2B ubiquitylation on a different site (i.e. K34ub) is able to directly stimulating DOT1L activity (Wu et al., 2011), support a model that H2B ubiquitylation leads to allosteric changes in nucleosomes to facilitate DOT1L binding in a catalytically competent manner (McGinty et al., 2008; Werner and Ruthenburg, 2011). So far, there has been no detailed biochemical study delineating the mechanism for crosstalk between H2Bub and H3 K4 methylation in vitro.

Unlike yeast, complexity of H3 K4 methylation in mammals increases dramatically (Dou and Hess, 2008). There are six H3 K4 methyltransferases including ySET1 ortholog SET1A, SET1B and four mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) family histone methyltransferases (HMTs) (i.e. MLL/MLL1, and MLL2-4) (Ruthenburg et al., 2007). These MLL family HMTs share a highly conserved core configuration comprised of RbBP5, ASH2L and WDR5 (Dou et al., 2006; Ruthenburg et al., 2007). Importantly, ySwd2 is not conserved in mammalian H3 K4 methylation machineries (Dou et al., 2005; Goo et al., 2003; Hughes et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2007a; Nakamura et al., 2002). Biochemical reconstitution study shows that the four-component MLL core complex that contains RbBP5, ASH2L, WDR5 and MLL SET, is able to recapitulate most activities of the MLL holo-complex (Dou et al., 2006) and is subject to regulation by H2Bub (Wu et al., 2011). These results raise the question on the conservation of the Swd2-dependent trans-regulation. Instead, they support distinct mechanisms for histone crosstalk between H2Bub and H3 K4 methylation in higher eukaryotes.

In addition to H2Bub, ubiquitylation on histone H2A tail (i.e. H2AK119ub) also plays a role in trans-tail regulation in higher eukaryotes. In contrast to H2BK120ub, H2AK119ub functions in coordination with repressive chromatin modifications to prevent transcription elongation by blocking the release of poised RNA Pol II (Stock et al., 2007) and by regulating higher order chromatin structures (Luger et al., 1997a). Recently, it is reported that H2AK119ub is capable of directly repressing H3 K27 methylation by the polycomb repressing complex 2 (PRC2) and H3 K4 methylation by MLL3 in higher eukaryotes (Nakagawa et al., 2008; Whitcomb et al., 2012). This raises questions on how ubiquitylation on histone H2A and H2B tails exert different regulations for H3 methylation and do they involve the same or different mechanisms?

Here, we report the extensive biochemical study for trans-regulation of mammalian MLL family HMTs. We demonstrate that trans-regulation of H3 K4 methylation employs different mechanisms from those of H2Bub mediated DOT1L activation and H2Aub mediated H3 K4 repression. The N-terminal winged helix (WH) motif of ASH2L is essential for H2Bub mediated trans-regulation. Mutating a key residue in the ASH2L WH motif (K99) reduces its affinity with ubiquitylated nucleosomes and abolishes H2Bub-dependent trans-regulation. We further demonstrate that this trans-regulation does not require ubiquitin to be physically attached to nucleosome core particles or even on histones to exert regulatory effects. ASH2L with ubiquitin covalently linked at N-terminus is able to enhance MLL activity for mono-, di- and tri-methylation, similar to H2Bub-dependent trans-regulation. Furthermore, we show that not all MLL family HMTs are subject to H2Bub regulation, highlighting complexity of ubiquitylation signaling in higher eukaryotes.

RESULTS

ASH2L N-terminus is essential for H2Bub-mediated histone crosstalk

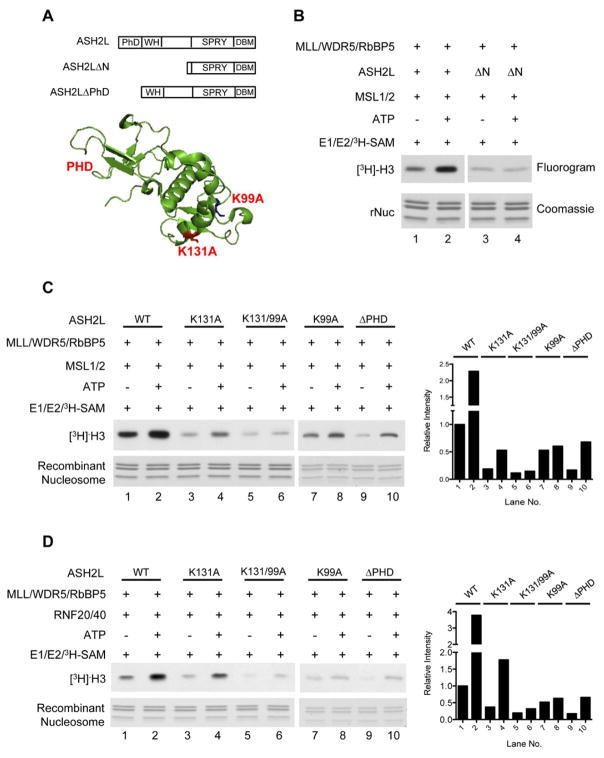

Our previous study showed that H2Bub was able to stimulate the activity of the MLL core complex in a highly purified in vitro system (Wu et al., 2011), which included MLL SET, RbBP5, ASH2L and WDR5 (Dou et al., 2006). This implies that trans-regulation of mammalian H3 K4 HMTs may employ a distinct mechanism from that in yeast, which depends on a yeast-specific Swd2 protein (Lee et al., 2007b; Vitaliano-Prunier et al., 2008). To examine the detailed molecular mechanism for the conserved histone crosstalk in higher eukaryotes, we used MSL1/2 ubiquitylated recombinant nucleosomes as substrates for the in vitro HMT assay. In each scenario, mock ubiquitylation reaction without ATP was used as the negative control. Consistent with previous observation, MSL1/2 mediated ubiquitylation (Supplementary Figure 2A) enhanced the activity of the MLL core complex (Figure 1B, lane 2 vs. 1). Using this assay, we tested various truncation mutants of the MLL core components and found that N-terminal deletion of ASH2L (1-275aa) abolished MSL1/2-dependent stimulation (Figure 1B, lane 4 vs. 3 and data not shown). Although the overall activity of the MLL core complex with ASH2L ΔN was lower than that of the wild type complex (Figure 1B, lane 3 vs. 1), it was indistinguishable for nucleosomes with or without H2BK34ub (Figure 1B, lane 4 vs. 3). This suggests that although ASH2L C-terminal SPRY domain is sufficient to support MLL activity on free histone H3 or H3 peptides (Cao et al., 2010), N-terminus of ASH2L protein is required for both H2Bub stimulation and optimal MLL activity on nucleosome substrates.

Figure 1. ASH2L WH motif is essential for H2Bub-dependent MLL activity.

A. Top, the schematics of ASH2L domain organization. PHD, plant homeo domain, WH, winged helix; DBM, DPY30 binding domain. Bottom, the structure of ASH2L N-terminus PHD and WH domains (Chen et al., 2011). K131 and K99 are highlighted. (B–D). In vitro HMT assays with enzymes, cofactors, and substrates as indicated on top. Recombinant Xenopus nucleosomes and [3H]-SAM was used as the substrate. Top panel, histone H3 methylation was detected by autoradiograph for [3H]. Bottom panel, a duplicate gel of recombinant nucleosome was stained with coomassie as the loading control. In vitro histone ubiquitylation assays were performed using either MSL1/2 (B, C) or RNF20/40 (D) as the E3 ubiquitin ligase. Quantitation of the [3H]-H3 was presented, when applicable, as relative intensity to lane 1, which was arbitrarily set as 1. See also Supplementary Figure S1 and S2.

ASH2L winged-helix motif (WH) is important for ubiquitylation-dependent trans- regulation

ASH2L protein adopts a modular configuration including a PHD finger, a winged-helix (WH) motif, a SPRY domain and a DPY-30 binding motif (DBM) (Figure 1A). Given that ASH2L N-terminus is essential for histone ubiquitylation-methylation crosstalk, we further examined which of the domains, the PHD finger or the WH motif, is critical for trans-regulation. To this end, we reconstituted four different MLL core complexes containing the following ASH2L mutants in proper stoichiometry:ΔPHD, K131A, K99A and K131/99A (Supplementary Figure 1B). Mutating either K131 or K99 of the ASH2L WH motif leads to compromised ASH2L DNA binding in vitro and, specifically for K131A, reduced recruitment of ASH2L to Hox loci in cells (Chen et al., 2011).

We next tested these reconstituted complexes for their ability to perform H3 K4 methylation. As shown in Figure 1C, all ASH2L mutants affected overall activity of the MLL core complex on nucleosomes, which is indicative of their roles in regulating MLL methyltransferase activity. However, only ASH2L K99A or K131/K99A mutants further abolished MSL1/2-dependent H3 K4 methylation. The activities of MLL complexes with either K99A or K131/99A double mutants were the same with or without MSL1/2 dependent H2B ubiquitylation (Figure 1C, lane 5 vs. 6 and lane 7 vs. 8). This result suggests that ASH2L K99 is essential for mediating trans-regulation between H2BK34ub and H3 K4 methylation. In contrast, mutation of K131 or deletion of the N-terminal PHD finger had no effects on H2Bub-dependent activation. To further examine whether this is specific for MSL1/2 mediated regulation (i.e. through H2BK34ub), we set up similar experiments using RNF20/40 as the E3 ubiquitin ligase (Supplementary Figure 2B). The results, shown in Figure 1D, demonstrated that K99 was essential for RNF20/40-mediated regulation (i.e. through H2BK120ub) as well. The MLL complex with ASH2L K99A or K131/99A mutation showed no RNF20/40-dependent increase of H3 K4 methylation (Figure 1D). Together, our in vitro HMT experiments showed that K99 in the ASH2L WH motif is critical for H2Bub-dependent crosstalk.

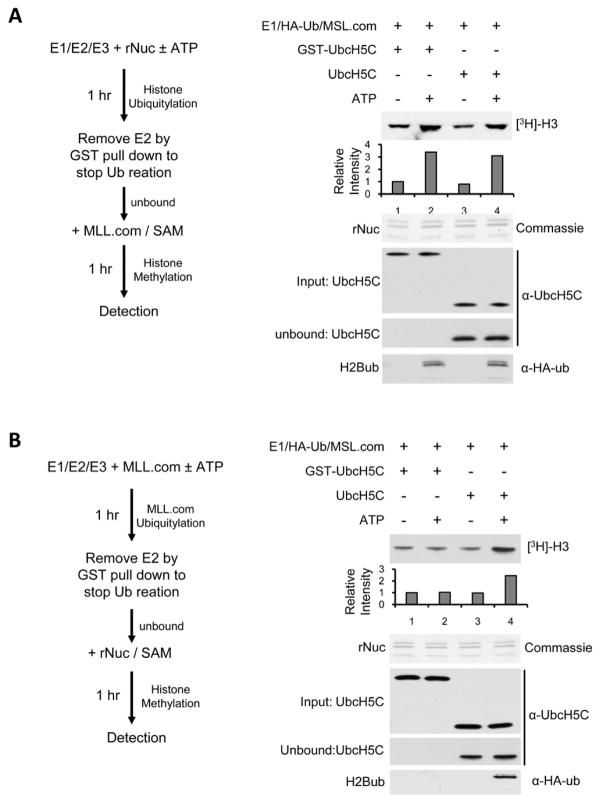

Histone ubiquitylation is the major contributor to trans-regulation in vitro

We previously demonstrated that mutation of MSL1/2 substrate H2BK34 to arginine (R) abolishes trans-regulation for MLL (Wu et al., 2011). Here, we decided to further test whether components of the MLL complex can be ubiquitylated in the in vitro assay and if yes, whether they contribute to trans-regulation in the same way as ySwd2 (Vitaliano-Prunier et al., 2008). To this end, we first tested MSL1/2 mediated ubiquitylation for each of the MLL core components in vitro. As shown in Supplementary Figure 3A, we were able to detect low level ASH2L ubiquitylation (ASH2Lub). Ubiquitylation of the other three proteins (i.e. RbBP5, WDR5 and MLL) was not detected under the same conditions (Supplementary Figure 3B–3D). Next, we set up a two-step procedure to distinguish the function of H2Bub versus ASH2Lub in the following methylation reaction (scheme see left panels in Figure 2A and 2B). Specifically, we performed a GST-pull down to remove GST-tagged E2 enzyme (GST-UbcH5C) before proceeding to histone methylation. This allowed us to stop ubiquitylation reaction for either nucleosome (2A) or the MLL complex (2B) before proceeding to histone methylation reaction. As control, we used untagged UbcH5C as E2 for mock GST-pull down. We found that prior ubiquitylation of nucleosomes was able to stimulate MLL methyltransferase activity on nucleosomal H3 (Figure 2A, right panel). The activity of the MLL complex was equally stimulated with or without removal of the E2 enzyme (Figure 2A, lane 2 vs. lane 4). In contrast, prior ubiquitylation of the MLL complex had no effects on the following H3 K4 methylation once ubcH5C was removed to prevent H2B ubiquitylation (Figure 2B, lane 2 vs. 4). These results support that H2Bub is the major contributor to trans-regulation under our assay conditions. Of note, given low level of ASH2Lub in our assay (Supplementary Figure 3A), we cannot rule out that our in vitro HMT assay is not sensitive enough to detect possible stimulation for MLL activity by ASH2Lub.

Figure 2. Ubiquitylation of nucleosomes but not MLL complex components contributes to trans-regulation of H3 K4 methylation.

A. Left, scheme of the experimental procedure. After in vitro ubiquitylation of recombinant nucleosomes by MSL1/2, GST-UbcH5C was removed by GST pull down. The nucleosome in the unbound fraction was subject to in vitro HMT assays by adding the MLL complex and [3H]-SAM. Right, in vitro HMT assays for recombinant nucleosomes. Methylated H3 was indicated as [3H]-H3. Quantitation of the [3H]-H3 was presented as relative intensity to lane 1, which was arbitrarily set as 1. Coomassie stained gel of the nucleosomes was included as the loading control. Bottom panels are western blots for input UbcH5C, unbound UbcH5C and ubiquitylated H2Bub as indicated on the left. Antibodies used for detection were indicated on the right. B. Left, scheme of the experimental procedure. After in vitro ubiquitylation of the MLL complex by MSL1/2, GST-UbcH5C was removed by GST pull down. The unbound fraction was further incubated with substrates nucleosomes and [3H]-SAM for in vitro HMT assays. Right, in vitro HMT assays for recombinant nucleosomes. Methylated H3 was indicated as [3H]-H3. Quantitation of the [3H]-H3 was presented as relative intensity to lane 1, which was arbitrarily set as 1. Coomassie stained gel of the nucleosomes was included as the loading control. Bottom panels are western blots for input UbcH5C, unbound UbcH5C and ubiquitylated H2Bub as indicated on the left. Antibodies used for detection were indicated on the right. See also Supplementary Figure S3.

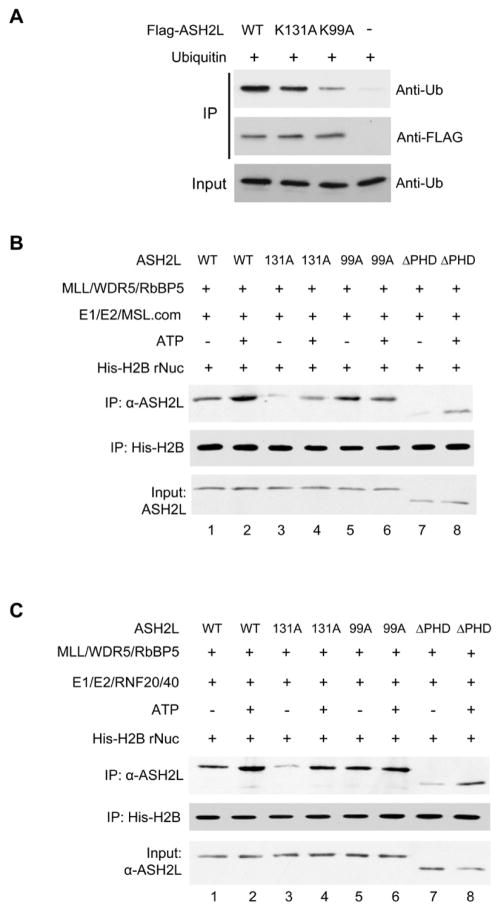

ASH2L K99A has reduced affinity for ubiquitylated nucleosomes

To further understand the role of ASH2L in trans-regulation, we tested whether ASH2L directly interacts with free ubiquitin and if so, whether K99 is essential for this interaction. To this end, we incubated FLAG-tagged wild type ASH2L, ASH2L K131A or ASH2L K99A with ubiquitin. After FLAG purification, we examined ubiquitin in the bound fraction by immunoblot. Mock purification without ASH2L was used as the negative control. As shown in Figure 3A, both wild type and K131A ASH2L were able to directly interact with ubiquitin, and this interaction was greatly reduced for K99A mutant under the same assay conditions, suggesting that ASH2L K99 is directly involved in the ubiquitin recognition.

Figure 3. ASH2L K99A reduces MLL affinity to ubiquitylated nucleosome.

A. Co-IP experiment using ubiquitin as well as Flag-tagged full-length wild type ASH2L, K99A or K131A mutants. Proteins bound to M2 beads were eluted and detected with anti-ubiquitin or anti-ASH2L antibodies as indicated. Immunoblot for ubiquitin in the input was included as controls. (B, C) Recombinant nucleosome containing His-tagged H2B was ubiquitylated in vitro by the MSL1/2 complex (B) or the RNF20/40 complex (C). The unmodified and ubiquitylated nucleosomes were divided and subject to pull down assays in the presence of wild type ASH2L or the ASH2L mutants as indicated on top. After Ni-NTA purification, the bound protein was eluted and detected with specific antibodies as indicated on left. Immunoblot for Ash2L in input was included as the control. See also Supplementary Figure S2D.

Since the ASH2L WH motif is involved in nucleosome interactions (Chen et al., 2011), a logical extension is to examine whether K99A mutant affects ASH2L binding to ubiquitylated nucleosomes. To this end, we reconstituted recombinant nucleosomes containing His-tagged H2B and subjected them to MSL1/2 (Figure 3B) or RNF20/40 (Figure 3C) mediated in vitro ubiquitylation. The unmodified and ubiquitylated nucleosomes were then mixed with wild type, K131A, K99A or ΔPHD ASH2L respectively for pull down experiments. Both ASH2L K131A and ASH2L ΔPHD had lower overall affinity for nucleosomes as compared to wild type ASH2L (Figure 3B, lane 3, 7 vs. 1), consistent with their respective role in mediating DNA (Chen et al., 2011) and histone binding (Supplementary Figure 2D). Despite weaker interaction, both ASH2L mutants showed higher affinity to nucleosomes ubiquitylated by either the MSL complex (Figure 3B) or RNF20/40 (Figure 3C). In contrast, ASH2L K99A had no preference for H2B ubiquitylated nucleosomes. It bound equally well to both unmodified and modified nucleosomes at a level comparable to wild type ASH2L (Figure 3B and 3C). These results suggest that: 1) ASH2L has higher affinity to H2B ubiquitylated nucleosomes, probably a result of its direct interaction with ubiquitin; 2) The preference of ASH2L for ubiquitylated nucleosomes requires K99 in the WH motif; and 3) K99A did not significantly affect ASH2L interaction with unmodified nucleosomes despite its role in DNA binding (Chen et al., 2011). This is consistent with moderate reduction of ASH2L K99A binding at Hox loci in cells (Chen et al., 2011).

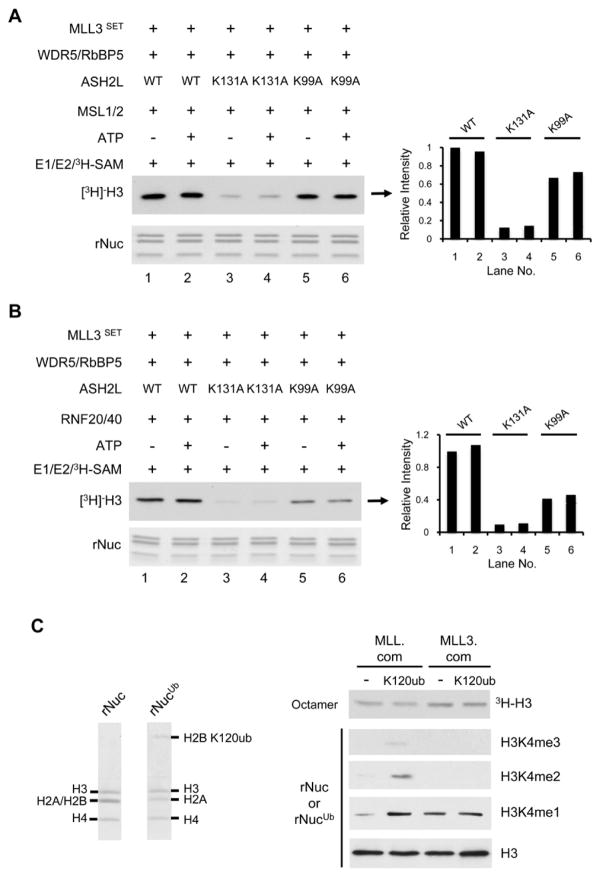

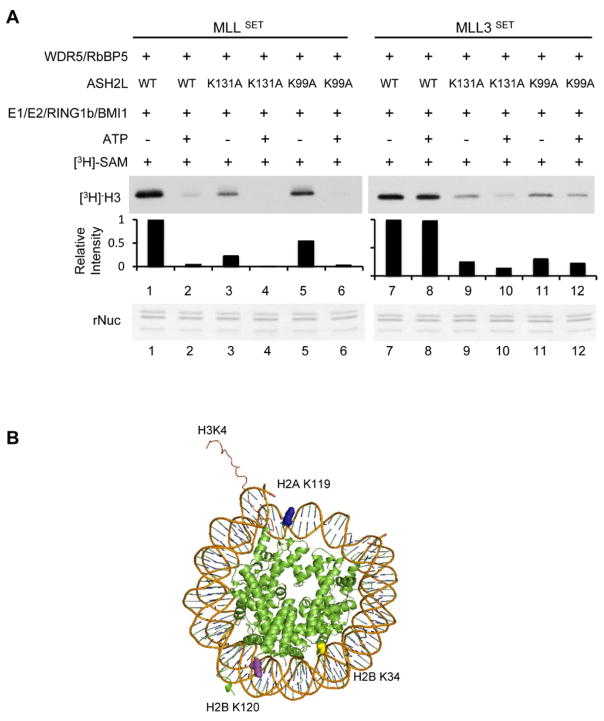

Trans-regulation of the MLL family histone methyltransferases

Complexity of the H3 K4 methylation machineries is a unique feature in higher eukaryotes (Ruthenburg et al., 2007). There are six MLL/hSET1 family HMTs that carry out H3 K4 methylation in mammals and they share a common set of core components including WDR5, RbBP5 and ASH2L (Dou et al., 2006). Despite extensive studies, it remains unclear whether all MLL family HMTs are regulated by H2Bub. We decided to examine trans-regulation for two other MLL family HMTs, hSET1 and MLL3. We asked whether hSET1 and MLL3 were subject to trans-regulation by H2Bub, and if yes, whether the ASH2L WH motif was required. To this end, we reconstituted the hSET1 and MLL3 core complexes containing wild type and ASH2L mutants (Supplementary Figure 1B, middle and bottom panels) and subject them to in vitro HMT assays. Like MLL, the hSET1 core complex showed higher methyltransferase activity on ubiquitylated nucleosomes (Supplementary Figure 4). The H2Bub dependent stimulation was greatly reduced by ASH2L K99A mutant in the same manner as it was in the MLL complex. Similarly, ASH2L K131A mutant, while affecting the overall activity of the hSET1 complex, had no effect on H2Bub-dependent stimulation. To our surprise, the MLL3 core complex did not show H2Bub-dependent stimulation despite highly conserved core complex configuration and sequence homology to the MLL SET domain (Figure 4). The activities of the MLL3 core complex were the same on nucleosomes with or without prior modifications by MSL1/2 (Figure 4A) or RNF20/40 (Figure 4B). Consistent with the lack of ubiquitylation-dependent stimulation, ASH2L K99A mutant had no effect on the overall activity of the MLL3 complex (Figure 4A and 4B). Of note, ASH2L K131A mutant consistently reduced the overall activity of the MLL3 core complex regardless of its ubiquitylation status (Figure 4A and 4B, lane 1 vs. 3). This suggests that the WH motif-mediated nucleosome interactions are generally required for the activity of the MLL family HMTs. The failure of MLL3 to show activation on ubiquitylated nucleosomes was not due to the low level of modification associated with the enzymatic assays. We performed similar in vitro HMT assays using recombinant nucleosomes containing either wild type or chemically synthesized H2BK120ub as substrates and the results were the same (Figure 4C). We found that the MLL3 core complex, surprisingly, was predominantly a H3 K4 mono-methyltransferase despite its sequence homology with MLLSET (Figure 4C) and this activity was not affected by H2BK120ub. In contrast, H2Bub was able to stimulate MLL activities for mono-, di- and tri-methylation in vitro. The increase of all three methylation states by H2BK120ub suggests that trans-regulation by H2Bub affects overall activity, not processivity, of the MLL complex. The diversity in H3 K4 methylation specificity and ubiquitin-dependent responses from the MLL family HMTs may reflect their yet to be characterized differences in higher eukaryotes.

Figure 4. Trans-regulation for different MLL family HMTs.

A. In vitro HMT assays using recombinant nucleosomes with or without prior ubiquitylation by MSL1/2 (A) or the RNF20/40 complex (B). Reactions for the MLL3 complex were set up as indicated on top. For both A and B, top panel is the fluorogram for [3H]-H3 methylation and bottom panel is coomassie-stained gel of the nucleosome substrate. Quantitation of the [3H]-H3 was presented as relative intensity to lane 1, which was arbitrarily set as 1. C. Left: coomassie-stained gel for unmodified recombinant nucleosomes (rNuc) and nucleosomes containing chemically synthesized H2BK120ub (rNucUb). Right: in vitro HMT assay using histone octamer or nucleosomes with or without H2BK120ub as substrates, as indicated on left. Either the MLL or MLL3 complex was used as indicated on top. H3 K4 mono-, di-, and tri-methylation were detected by immunoblot using antibodies as indicated on right. See also Supplementary Figure S5A.

Ubiquitin covalently attached at H2B N-terminus is able to stimulate MLL methyltransferase activity

Using chemically synthesized H2BK120, we found that H2Bub exerted its function only in the context of nucleosomes. Ubiquitin or free H2BK120ub (in histone octamer) could not regulate MLL activity in trans (Figure 4C, top panel). We envision three models by which nucleosomal H2Bub may regulate MLL overall activity: First, H2Bub may induce allosteric changes on nucleosomes that in turn enhance MLL activity through ASH2L. Second, H2Bub further stabilizes ASH2L interaction with ubiquitylated nucleosomes, in addition to its interaction with nucleosomal DNA and/or with histone H3 and H4. The increased affinity of ASH2L with ubiquitylated nucleosomes is sufficient for enhancing MLL activity. Third, stable ASH2L-ubiquitin interaction facilitates allosteric changes in the MLL complex, which is essential for optimal catalysis. To distinguish these models, we set up two separate experiments. First, we decided to move ubiquitin molecule away from nucleosome core particle by covalently linking it to the N-terminus of histone H2B (N-Ub-H2B) via a 30mer poly-linker (GS)30. We reconstituted the N-Ub-H2B into nucleosomes for in vitro HMT assays. As shown in Supplementary Figure 5, free N-Ub-H2B (in the form of histone octamer) had no effects on H3 K4 methylation. However, N-Ub-H2B was able to modestly enhance MLL activity in the context of nucleosomes (Supplementary Figure 5, right panel). As control, no effect on MLL3 activity was found by N-Ub-H2B (Supplementary Figure 5). Of note, stimulation of MLL activity by N-Ub-H2B was less apparent than that by H2BK120ub or H2BK34ub (see Figure 1C and 1D). Nonetheless, the ability of N-Ub-H2B to regulate MLL activity suggests that H2Bub mediated trans-regulation probably involves mechanisms beyond allosteric changes in nucleosome core particles.

Ubiquitin covalently attached to ASH2L or RbBP5 is able to stimulate MLL methyltransferase activity

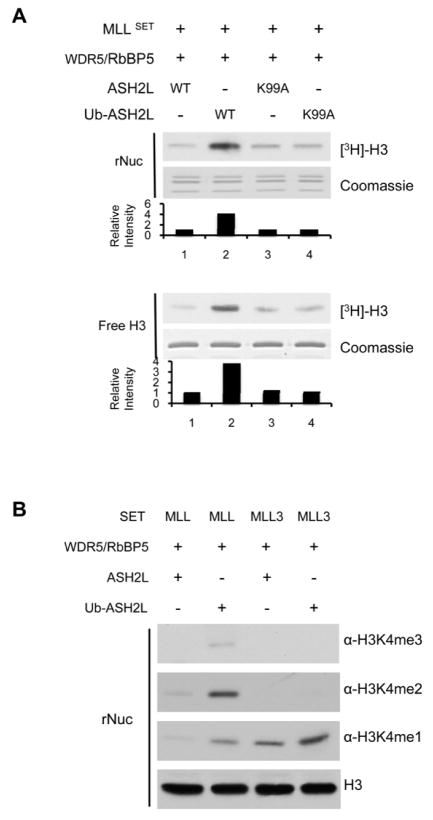

Given the results from the N-Ub-H2B experiment, we next tested whether ubiquitin on H2B serves only to stabilize ASH2L interaction with nucleosomes or it also facilitates allosteric changes through ASH2L, which lead to more efficient MLL catalysis. To distinguish these two possibilities, we made an ubiquitin-fusion protein, Ub-ASH2L, in which ubiquitin was covalently linked to ASH2L N-terminus (Supplementary Figure 6A). We also made additional Ub-fusion proteins for other MLL complex components including RbBP5 and WDR5 as controls (Supplementary Figure 6B). In all cases, an ubiquitin molecule was covalently attached to protein via the poly-linker (GS)30. The fusion proteins were incorporated into the MLL complex respectively, following the same stoichiometry as their wild type counterparts (Supplementary Figure 6). We reason that if ubiquitin serves only to stabilize ASH2L interaction with nucleosomes, then Ub-ASH2L may not affect the MLL methyltransferase activity. On the other hand, if ubiquitin serves to induce allosteric changes in the MLL complex, then ubiquitin stably positioned in the proximity of the ASH2L WH motif may be able to stimulate MLL activity as well. As shown in Figure 5A, Ub-ASH2L was able to enhance the MLL methyltransferase activity on nucleosomal H3 in the absence of H2Bub. Similar to H2BK120ub, Ub-ASH2L was able to enhance overall activity of MLL for mono-, di-, and tri-methylation of nucleosomal H3K4 while it was not able to regulate MLL3 activity (Figure 5B). Importantly, mutation of K99A in Ub-ASH2L compromised MLL stimulation, suggesting K99 is the key residue to mediate the conformational change in the MLL complex. In further support of the dispensable role of nucleosomes, Ub-ASH2L was able to enhance methylation of free histone H3 without the nucleosome context (Figure 5A, bottom panels). Taken together, our results suggest that ubiquitin functions at least in part through ASH2L to induce allosteric changes in the MLL complex to achieve higher methyltransferase activity.

Figure 5. Regulation of MLL activity Ub-fusion proteins.

A. In vitro HMT assays for the reconstituted MLL core complexes containing ASH2L, ASH2L K99A, Ub-ASH2L or Ub-ASH2L K99A as indicated on top. Recombinant nucleosome (rNuc) or free H3 was used as substrates as indicated on left. For each substrate, top panel is the fluorogram for [3H]-H3 methylation detection and bottom panel is the coomassie stained gel for either nucleosomes or free histone H3 substrate. Quantitation of the [3H]-H3 was presented as relative intensity to lane 1, which was arbitrarily set as 1. B. In vitro HMT assay using MLL or MLL3 complexes with ASH2L or Ub-ASH2L as indicated on top. Unmodified nucleosomes were used as the substrate and H3 K4 mono-, di-, or tri-methylation was analyzed by immunoblot using antibodies as indicated on right. See also Supplementary Figure S6 and S7.

Interestingly, Ub-RbBP5, but not Ub-WDR5, was also able to regulate MLL activity on unmodified nucleosomes, albeit to a lesser extent (Supplementary Figure 7). This regulation was significantly compromised by ASH2L K99A mutation. Of note, RbBP5 forms a stable heterodimer with ASH2L while WDR5 has no direct interaction with ASH2L in the MLL complex (Cao et al., 2010; Dou et al., 2006). These results suggest that ubiquitin needs to be in close proximity of ASH2L to be effective in trans-regulation (see Discussion).

Regulation of H3 K4 methylation by H2A ubiquitylation involves distinct mechanisms

To further explore the spatial requirement of ubiquitin position, we examined how another important histone ubiquitylation event, i.e. histone H2Aub by RING1b/BMI1, affects the MLL activity. To this end, we used H2A ubiquitylated nucleosomes (Supplementary Figure 2C) as substrates for in vitro HMT assays. In contrast to H2Bub, RING1b/BMI1 mediated H2Aub drastically reduced H3 methylation by the MLL core complex (Figure 6A). This repression was not mediated by the ASH2L WH motif since the MLL complexes containing either ASH2L K133A or K99A mutant were similarly affected (Figure 6A). The activity of the MLL3 core complex was also modestly affected by H2Aub (Figure 6A), consistent with a previous report (Nakagawa et al., 2008). The dispensability of ASH2L in H2Aub mediated repression as well as repression of both MLL and MLL3 by H2AK119ub suggest that these two trans-regulation events likely involve distinct mechanisms. Given the close proximity of H2AK119ub to H3 tail (Figure 6B, Luger et al., 1997), H2AK119ub could affect MLL activity by direct steric hindrance of the enzyme-substrate interaction, a hypothesis proposed for H2AK119ub mediated repression of H3 K27 methylation (Whitcomb et al., 2012). Repression of activities of the antagonistic PRC2 and MLL complexes by H2AK119ub reveals the dual role of H2Aub by RING1b/BMI1 in regulating H3 methylation, which will be of interest for future studies.

Figure 6. Trans-regulation of H3 K4 methylation by H2AK119ub.

A. In vitro HMT assays using MLL (left) or MLL3 (right) complex containing wild type ASH2L or ASH2L mutants as indicated on top. The substrate is recombinant nucleosomes with or without prior ubiquitylation by the RING1B/BMI1 complex. Fluorogram for [3H]-H3 methylation was included. Quantitation of the [3H]-H3 was presented as relative intensity to lane 1 (MLL) or lane 7 (MLL3), which was arbitrarily set as 1. Bottom panel is the coomassie stained gel for recombinant nucleosomes as loading controls. B. Schematics for nucleosome structures (PDB: 1AOI, Luger et al., 1997). Different lysine residues discussed in the text are highlighted. See also Supplementary Figure S1 and S2.

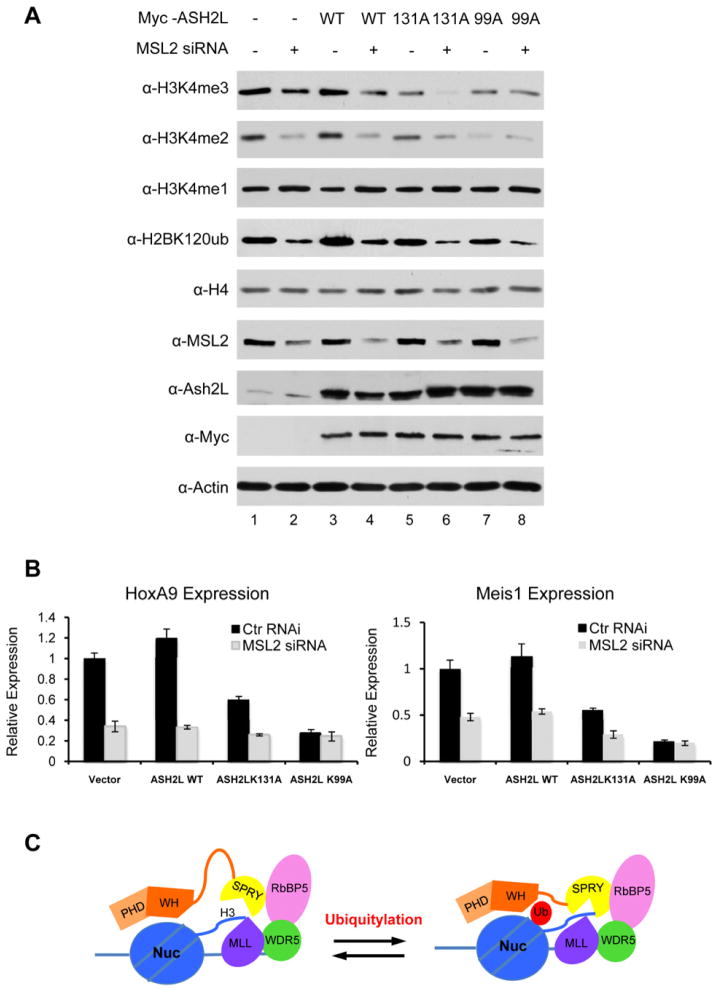

ASH2L regulates H2Bub dependent H3 K4 methylation in cells

After establishing the role of ASH2L in regulating crosstalk between H2Bub and H3 K4 methylation in vitro, we further tested cellular functions of this crosstalk in HeLa cells. Since MSL2 affected both H2B K120ub and K34ub in cells (Figure 7A, Wu et al., 2011), knocking down MSL2 by siRNAs led to global reduction of H3 K4 methylation (Figure 7A, Wu et al., 2011). The reduction of H3 K4 methylation by MSL2 siRNAs was also observed in cells overexpressing wild type ASH2L or ASH2L K131A mutant, suggesting that these two exogenous ASH2L proteins were subject to regulation by H2Bub (Figure 7A, lane 4 vs. 3 and lane 6 vs.5). In contrast, cells overexpressing ASH2L K99A showed defects in response to trans-regulation since H3 K4 methylation was not changed upon MSL2 depletion (Figure 7A, lane 7 vs. 8). Of note, in all cases, exogenous myc-ASH2L was expressed at much higher level than endogenous ASH2L and as a result, ASH2L mutants acted as dominant negative in the cells (Figure 7A). There are several things worth notice: 1) both ASH2L WH mutants affect global H3K4 methylation even without MSL2 knockdown. The effects seem to be more pronounced on H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 than on H3K4me1 in cells. This is probably due to the presence of mono-methyltransferases (e.g. SET7/9 and MLL3) and/or other indirectly involved activities in cells (Figure 4C); 2) lower level of H3K4me2 in cells overexpressing ASH2L K99A (as compared to ASH2L K131A) was probably due to its higher expression level, although we could not rule out other contributing factors in cells; and 3) reduction of H3 K4 methylation was not due to indirect effects on MLL transcripts upon MSL2 knockdown or overexpression of ASH2L mutants (Wu et al., 2011 and data not shown).

Figure 7. ASH2L regulated H2Bub-dependent H3K4 methylation in cells.

A. Immunoblot for proteins or histone modifications as indicated on left. Vectors expressing Myc-tagged ASH2L, ASH2L mutants as well as control or MSL2 siRNAs were transfected into HeLa cells as indicated on top. Immunoblot for H4 and Actin were included as loading controls. B. RT-PCR for HOXA9 (left) and MEIS1 (right) expression in HeLa cells transfected with vectors expressing wild type ASH2L, ASH2L mutants as well as control or MSL2 siRNAs as indicated. Gene expression was normalized against GAPDH and presented as fold change against sample transfected with vector and control siRNA, which is arbitrarily set at 1. Means and standard deviations (as error bars) from at least three independent experiments were presented. C. The model for trans-regulation of H3 K4 methylation. In this model, we hypothesize that ASH2L binds to nucleosome substrates through the N-terminal PHD domain and the WH motif. Its C-terminal SPRY domain engages the MLLSET domain through both RbBP5/WDR5 (Dou et al, 2006) and substrates (Cao et al., 2010). Upon H2B ubiquitylation, the ASH2L WH motif directly interacts with ubiquitin, which in turn leads to allosteric changes in ASH2L/MLL for optimal methyltransferase activity. See also Supplementary Figure S7.

Consistent with changes in H3 K4 methylation, expression of MLL targets, HOXA9 and MEIS1, was reduced in HeLa cells treated with MSL2 siRNAs. The MSL2 knockdown induced gene down-regulation was also observed in cells overexpressing ASH2L WT and K131A (Figure 7B). Both genes were down regulated upon MSL2 siRNA treatment (Figure 7B). In contrast, despite lower expression of HOXA9 and MEIS1 in cells overexpressing ASH2L K99A, they were not affected by MSL2 knockdown, suggesting defects in trans-regulation by H2Bub.

DISCUSSION

Our study here uses a well-defined biochemical system to study H2Bub-dependent regulation of the MLL family HMTs in higher eukaryotes. We demonstrate that this regulation depends on the N-terminal WH motif of ASH2L, a core subunit of the MLL complex. Mutation of K99, a residue in the WH motif, leads to disruption of H2Bub-dependent trans-regulation. Importantly, ASH2L with ubiquitin attached at N-terminus is capable of stimulating overall MLL activity on both nucleosomes and free histone H3, in the same manner as H2Bub dependent regulation. Our results suggest that H2Bub-H3K4me crosstalk occur in trans and serves to increase the overall activity of the MLL complex. This model, which is in contrast to H2Bub dependent regulation of DOT1L, significantly widens the scope of H3K4me regulation and supports a potentially broader functional connection between protein ubiquitylation and histone methylation. Our study also highlights the diverse responses of the MLL family HMTs to histone ubiquitylation in higher eukaryotes.

Distinct mechanisms for regulation of H3 K4 vs. K79 methylation by H2Bub

It is well established that H2Bub regulates both H3 K4 and H3 K79 methylation. While the mechanism for H2Bub regulation of DOT1L/H3K79me is well studied, it remains unclear how H2Bub regulates MLL/H3K4me in higher eukaryotes. Our study here shows that these two histone crosstalk events probably have different underlying mechanisms, exemplified in the following observations: 1) H2Bub enhances DOT1L mediated methylation in an intra-nucleosomal fashion. Efficient methylation of H3 K79 requires the presence of H2Bub in cis (i.e. on same nucleosome) (McGinty et al., 2008). On the contrary, ubiquitin-dependent regulation of H3 K4 methylation can occurs in trans. Ubiquitin can be either on nucleosomal H2B or on ASH2L to stimulate H3K4 methylation. In the latter cases, intact nucleosome is optional and enhanced activity can be observed on free histone H3 (Figure 5A, bottom panel and Supplementary Figure 7A and 7B). Of note, free ubiquitin or H2Bub are not able to stimulate MLL activity in trans, suggesting additional protein-protein or protein-DNA contacts are needed to stabilize ASH2L-ubiquitin interactions; 2) DOT1L recruitment to mono-nucleosome is not a function of ubiquitylation. DOT1L has similar affinities for both ubiquitylated and unmodified nucleosomes. (McGinty et al., 2008). This suggests that ubiquitin probably induces allosteric changes in nucleosomes, which can then be sensed by DOT1L for optimal activity. In contrast, ASH2L has higher affinity for the ubiquitylated nucleosomes (Figure 3B and 3C) and directly interacts with ubiquitin (Figure 3A). Direct interaction of ASH2L and ubiquitin probably enhance H3 K4 methylation by inducing allosteric changes in the enzyme, not the substrate. In further support, we found that ubiquitin placed ~60 amino acids away from nucleosome core particle (via a (GS)30 poly-linker) is able to increase H3 K4 methylation by MLL (Supplementary Figure 5).

The adoption of two distinct mechanisms for H2Bub-dependent regulation probably reflects the relative positions of H3 K4 and H3 K79 in the nucleosome and their accessibility to their respective modifying enzymes. We envision that the partially accessible position of H3 K79 requires ubiquitylation-induced conformational changes to alter intrinsic nucleosome stability and/or surface charges to allow DOT1L binding in a catalytically competent manner (McGinty et al., 2008; Werner and Ruthenburg, 2011). As a result, the crosstalk is restricted to modifications on the same nucleosome. In contrast, K4 at H3 N-terminus is fully accessible to the enzyme without changes in nucleosome core particles. In this case, ubiquitin (on H2B or on nonhistone proteins) is able to stimulate the enzymatic activity of the MLL complex through direct contact with ASH2L. Communications between ubiquitin and H3 K4 machinery are not necessarily restricted to nucleosomes or even chromatins as long as ubiquitin-ASH2L interaction can be stabilized. This predicts a much broader implication for signal transduction from protein ubiquitylation to methylation beyond the crosstalk of H2Bub and H3 K4 methylation, which will be of interest for future studies.

Given that H2Bub, but not H2Aub, is able to regulate MLL activity through ASH2L, the relative position of ubiquitin to ASH2L and/or the MLL SET domain seem to be important for this trans-regulation. It is likely that the MLL core complex interacts with nucleosomes in a specific manner, allowing optimal alignment of the active site to H3 substrate. Future structural studies of the MLL complex with nucleosomes are necessary for complete understanding of this trans-regulation.

The common feature of H2Bub mediated H3 K4 and K79 methylation

Despite distinct mechanisms, regulation of H3 K4 and K79 methylation by H2Bub shares some common features. Similar to DOT1L (McGinty et al., 2008), H2Bub is able to stimulate the overall activity of the MLL complex. Although the MLL complex predominantly catalyzes mono- and di-methylation, H2Bub promotes all three H3 K4 methylation states (Figure 4C). Of note, previous yeast genetic analyses show that H2Bub affects H3K4me2 and H3K4me3, but not H3K4me1 in cells (Dehe et al., 2006; Shahbazian et al., 2005), supporting a role of H2Bub in regulating ySET1 processivity. We find similar reduction of H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 by overexpression of dominant negative mutants for ASH2L (Figure 7A) or by knocking down ASH2L gene in HeLa cells (Dou et al., 2006). However, the results from our in vitro biochemical analyses clearly indicate that all three states of H3 K4 methylation are greatly enhanced by H2Bub or by Ub-ASH2L (Figure 4C and 5B). Therefore, results from the cellular assays are likely due to combined effects of multiplicity of the MLL family HMTs as well as changes in chromatin factors directly or indirectly involved in H3 K4 regulation. Our finding here stresses the importance of using in vitro biochemical assays to directly assess enzyme processivity to avoid complications in data interpretation. Another common feature for trans-regulation of H3 K4 and K79 methylation is that ubiquitylation of lysine side chain is not required (Figure 5A and Chatterjee et al., 2010). Ubiquitin can be chemically attached to a cystein residue on H2B (in the case of K79) or at the N-terminus of non-histone proteins (in the case of K4) through a poly-linker, while remaining effective in the trans-regulation. In both cases, there is flexibility in ubiquitin anchoring sites as well.

Role of ASH2L WH motif in the regulation of crosstalk in trans

One surprising finding of our study is that H2Bub mediated trans-regulation depends on the ASH2L WH motif, a region far away from the catalytic site. We have previously shown that ASH2L is unique in the regulation of MLL activity since its C-terminal SPRY domain is part of the active site and stabilizes interaction of MLL SET with substrates (Cao et al., 2010). Here we show that ASH2L N-terminus also plays a role in regulating MLL methyltransferase activity in the following aspects: 1) ASH2L-N enhances overall H3K4 methylation through binding to nucleosome substrates. This is mediated through histone H3/H4 interactions by PHD (Supplementary Figure 2D) and through DNA interaction by the WH motif (Chen et al., 2011, and Figure 1C and 1D); and 2) ASH2L-N mediates interaction with ubiquitin. Interestingly, the ASH2L WH motif is involved in both functions and mutation of two residues in the WH motif (i.e. K131A and K99A) compromises each of these two functions respectively. Specifically, ASH2L K131A has drastically reduced affinity for both DNA (Chen et al., 2011) and the nucleosome (Figure 3), which leads to reduced overall activity of the MLL complex. On the other hand, ASH2L K99A disrupts ubiquitin interaction and abolishes ubiquitin-dependent regulation of H3 K4 methylation. Distinct outcomes from these two mutants show that ASH2L binding to nucleosomes per se is not sufficient for trans-regulation. Therefore, ubiquitin likely provides additional signals through ASH2L to enhance MLL activity. Indeed, when ubiquitin is placed on ASH2L or RbBP5, the trans-regulation for H3 methylation is preserved. Future studies are needed to address how ubiquitylation signal is communicated to the MLL catalytic site to enhance its activity. It is possible that ubiquitin induces conformational changes in ASH2L, which leads to changes in the MLL core complex for optimal catalysis (Figure 7C).

Interestingly, we find that ASH2L can be weakly ubiquitylated by MSL1/2 in vitro (Supplementary Figure 3A). Although we cannot detect ASH2Lub-dependent stimulation of MLL activity under our assay conditions (Figure 2B), our result does not rule out the possibility that ASH2L ubiquitylation at higher level may play a role in this trans-regulation. In this context, ASH2L ubiquitylation could induce similar conformational change in the MLL complex, which leads to further activation. In light of this possibility, we noticed that a previous study in yeast has shown that Swd2, an ySET1 complex component is ubiquitylated and its ubiquitylation is required for recruitment of Spp1, an ySET1 protein that shares ASH2L N-terminal domain structures, and is required for Rad6/Bre1 mediated H3 K4 methylation (Vitaliano-Prunier et al., 2008). It will be interesting to test if histone crosstalk is regulated by a conserved mechanism through protein ubiquitylation.

Distinct function and regulation of the MLL family HMTs

Unlike yeast, mammals have six members in the MLL family H3 K4 methyltransferases. Given their ubiquitous expression patterns, it is likely that there is functional specification for each of the MLL family HMTs in higher eukaryotes. In support, these MLL family genes are essential and show distinct phenotypes when deleted in mice (Glaser et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2006; Yu et al., 1995). Mutations of each MLL family members are often found in distinct human diseases. This presents the most important distinction from yeast and suggests that these MLL family HMTs may be either intrinsically different or regulated differently for their respective activities and/or recruitment to target genes. One unexpected revelation from our study is the difference of MLL and MLL3 enzymatic activities and their responses to regulation by histone ubiquitylation. In particular, we find that MLL3 is a H3 K4 mono-methyltransferase for both free histone H3 and nucleosome substrates in vitro. Of note, a couple of previous studies showed that MLL3 (also called HALR) was capable of mono-, di-and tri-methylation of H3 K4 (Nakagawa et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2007). However, these studies did not rule out activities from other co-purified HMTs. More importantly, MLL3 activity is not regulated by H2Bub and only modestly responsive to H2Aub. In contrast, MLL was significantly affected by both H2Bub mediated activation and H2Aub mediated repression, albeit through different mechanisms. One possible explanation is that the MLL3 SET domain has much higher basal activity than that of MLL in our in vitro HMT assays (data not shown), suggesting that it may be in a default active state. In this case, it is likely that no further conformational changes induced by either H2Bub or Ub-ASH2L are needed for its optimal activity. In contrast, MLL SET is an extremely weak enzyme (Dou et al., 2006; Southall et al., 2009), making additional regulation a necessity. Although our results highlight potential functional and regulatory specification of the MLL family HMTs in higher eukaryotes, the detailed mechanism for histone ubiquitylation mediated trans-regulation of each the MLL family HMTs still awaits future comparative studies.

Experimental Procedure

Preparation of Histones, Recombinant Nucleosomes and HeLa Nucleosomes

Wild type Xenopus H2A, H2B, H3, H4 as well as several H2B mutants were expressed and purified according to (Luger et al., 1997b). Recombinant nucleosome is constituted by salt dialysis. Basically, DNA fragment containing 601 nucleosomes localization signal was mixed with histone octamer in high salt buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 M NaCl, 1mMDTT, 0.5M EDTA). The samples were then dialyzed at 4°C against gradu al change to low salt buffer (20mM Tris-HCl, 0.05M NaCl, 1mMDTT, 0.5M EDTA) at a rate of 0.8ml/min. The nucleosomes were further purified on preparative PAGE gel. Purified mono-nucleosomes could be visualized on 4.5% native gel after ethidium bromide staining.

HeLa nucleosomes were made as previously described (Dou et al., 2005). Basically, HeLa nuclear pellets were extensively washed in 0.4M NaCl followed by 0.65M NaCl wash. The soluble fraction from the high salt wash was dialyzed against 0.1M NaCl and subject to Micrococcal Nuclease digestion to get either mono- or oligo-nucleosomes, which were further purified by the Sephrose 6L column.

Plasmids and Recombinant Proteins

RbBP5, WDR5, Wild type, K99A and K131A of human Ash2L, SET domain of MLL, MLL3 and Set1 constructs were cloned in pET28a-based SUMO vector for bacterial expression. The cDNA of ubiquitin was linked to the N terminus of Ash2L, RbBP5 and H2B, which are sub cloned to pET28a vector for ubiquitylated-protein expression. Ubiquitin, Flag-Ash2L and its mutants were also constructed into pET28a vector. The other constructs including MSL1, MSL2, RNF20, RNF40 were made as previously described (Wu et al., 2011).

In vitro Histone Ubiquitylation and Methylation assays

For in vitro histone ubiquitylation assays, 100 ng E1, 500 ng E2, and 1ug different E3 complexes were used. They were incubated with 1ug HA-ubiquitin, 1ug free histones or nucleosomes in 20 ul reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaF, 0.5 mM DTT, and 4 mM ATP) at 30 °C for 1hour. The reactions were stopped by adding 2XSDS loading buffer and were subject to immunoblot with anti-HA antibody for ubiquitylated molecules, by anti-H2B K120ub or anti-H2A K119ub antibodies for specific lysine ubiquitylation. hE1 (E-304), hRAD6B (E2-613), hUbcH5c (E2-627), hUbcH13 (E2-664) and HA-ubiquitin (U-110) were obtained from Boston Biochem.

For in vitro histone methylation (HMT) assay, the complete ubiquitylation reaction (above) with or without ATP was further incubated with 5ul HMT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10% glycerol) in the presence of 10uM H3-SAM, 100ng recombinant MLL complex (total protein amount) or DOT1L at 30°C for one hour. The methylat ion was detected by autoradiograph.

Overexpression and Knockdown Experiments

For over expression study, vectors expressing Myc-tagged ASH2L, ASH2L K131A and ASH2L K99A were co-transfected into HeLa cells. For knockdown experiments, HeLa cells were transfected with control or MSL2L shRNA vectors (Sigma Mission) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as previously described (Wu et al., 2011). Total histone from these samples was acid extracted 48-hour after last transfection as described (Dou et al., 1999).

Nucleosome pull-down and Co-IP experiments

The His-tagged nucleosome and target MLL complex were mixed together in binding buffer (0.1% NP-40, 0.5mg/ml BSA, 250mM NaCl, Tris-HCl pH7.5, 20mM Imidazole) for 1 hour and then incubated with 30μL Ni-NTA slurry for 3 hours. After washes with the binding buffer, bound proteins were eluted with 250mM imidazole and 100mM NaCl. The eluted proteins were blotted for ASH2L.

For Co-IP experiment, purified His-Flag-Ash2L WT, K99A, and K131A protein were mixed with ubiquitin in binding buffer (0.1% NP-40, 0.5mg/ml BSA, NaCl 250mM, Tris-HCl pH 7.5). The mixture was bound with flag beads for 3 hours before bound proteins were eluted with 20mM Flag peptide and detected by immunoblot.

Antibodies

The antibodies for H3K4 trimethylation, dimethylation and monomethylation (Millipore), H2B K120 ubiquitylation (Millipore, 05-1312), anti-FLAG (Sigma, F-1840); anti-His (Qiagen, 34670); anti-HA (Covance, MMS-101R); anti-H4 (Millipore, 17-10047); anti-H2B (Abcam, ab18977); anti-Actin (Sigma, A3853); anti-Ash2L (Bethyl, A300-489A); anti-ubiquitin (SantaCruz, SC-9133) were obtained commercially. Anti-MSL2 antibody was made as previously described (Wu et al., 2011).

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

ASH2L WH motif is important for trans-regulation of H3 K4 methylation by H2Bub

Ub stimulates MLL activity in trans, in contrast to DOT1L regulation by H2Bub

H2Bub enhances MLL, but not MLL3, methyltransferase activity

H2Aub directly represses MLL methyltransferase activity

Acknowledgments

This work is supported grants from NIGMS (GM082856), American Cancer Society (ACS), SU2C and Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar to YD. We are grateful to Drs. Ming Lei and Yong Chen for the expression vectors for ASH2L, MLL and MLL3 SET domains as well as general discussions of the project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Briggs SD, Xiao T, Sun ZW, Caldwell JA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Allis CD, Strahl BD. Gene silencing: trans-histone regulatory pathway in chromatin. Nature. 2002;418:498. doi: 10.1038/nature00970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao F, Chen Y, Cierpicki T, Liu Y, Basrur V, Lei M, Dou Y. An Ash2L/RbBP5 heterodimer stimulates the MLL1 methyltransferase activity through coordinated substrate interactions with the MLL1 SET domain. PloS one. 2010;5:e14102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee C, McGinty RK, Fierz B, Muir TW. Disulfide-directed histone ubiquitylation reveals plasticity in hDot1L activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:267–269. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary K, Deb S, Moniaux N, Ponnusamy MP, Batra SK. Human RNA polymerase II-associated factor complex: dysregulation in cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:7499–7507. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wan B, Wang KC, Cao F, Yang Y, Protacio A, Dou Y, Chang HY, Lei M. Crystal structure of the N-terminal region of human Ash2L shows a winged-helix motif involved in DNA binding. EMBO reports. 2011;12:797–803. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehe PM, Dichtl B, Schaft D, Roguev A, Pamblanco M, Lebrun R, Rodriguez-Gil A, Mkandawire M, Landsberg K, Shevchenko A, et al. Protein interactions within the Set1 complex and their roles in the regulation of histone 3 lysine 4 methylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35404–35412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Hess JL. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by MLL and its disruption in acute leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:10–18. doi: 10.1007/s12185-007-0009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Milne TA, Ruthenburg AJ, Lee S, Lee JW, Verdine GL, Allis CD, Roeder RG. Regulation of MLL1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity by its core components. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:713–719. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Milne TA, Tackett AJ, Smith ER, Fukuda A, Wysocka J, Allis CD, Chait BT, Hess JL, Roeder RG. Physical association and coordinate function of the H3 K4 methyltransferase MLL1 and the H4 K16 acetyltransferase MOF. Cell. 2005;121:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Mizzen CA, Abrams M, Allis CD, Gorovsky MA. Phosphorylation of linker histone H1 regulates gene expression in vivo by mimicking H1 removal. Mol Cell. 1999;4:641–647. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierz B, Chatterjee C, McGinty RK, Bar-Dagan M, Raleigh DP, Muir TW. Histone H2B ubiquitylation disrupts local and higher-order chromatin compaction. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:113–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AB, Kao CF, Hillyer C, Pikaart M, Osley MA. H2B ubiquitylation plays a role in nucleosome dynamics during transcription elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser S, Lubitz S, Loveland KL, Ohbo K, Robb L, Schwenk F, Seibler J, Roellig D, Kranz A, Anastassiadis K, et al. The histone 3 lysine 4 methyltransferase, Mll2, is only required briefly in development and spermatogenesis. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goo YH, Sohn YC, Kim DH, Kim SW, Kang MJ, Jung DJ, Kwak E, Barlev NA, Berger SL, Chow VT, et al. Activating signal cointegrator 2 belongs to a novel steady-state complex that contains a subset of trithorax group proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:140–149. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.140-149.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Martel I, Yu H, Affar el B. Roles of ubiquitin signaling in transcription regulation. Cell Signal. 2012;24:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CM, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Milne TA, Copeland TD, Levine SS, Lee JC, Hayes DN, Shanmugam KS, Bhattacharjee A, Biondi CA, et al. Menin associates with a trithorax family histone methyltransferase complex and with the hoxc8 locus. Mol Cell. 2004;13:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WW, Venkatasubrahmanyam S, Ianculescu AG, Tong A, Boone C, Madhani HD. A conserved RING finger protein required for histone H2B monoubiquitination and cell size control. Mol Cell. 2003;11:261–266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00826-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Guermah M, McGinty RK, Lee JS, Tang Z, Milne TA, Shilatifard A, Muir TW, Roeder RG. RAD6-Mediated transcription-coupled H2B ubiquitylation directly stimulates H3K4 methylation in human cells. Cell. 2009;137:459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laribee RN, Fuchs SM, Strahl BD. H2B ubiquitylation in transcriptional control: a FACT-finding mission. Genes Dev. 2007;21:737–743. doi: 10.1101/gad.1541507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham JA, Chosed RJ, Wang S, Dent SY. Chromatin signaling to kinetochores: transregulation of Dam1 methylation by histone H2B ubiquitination. Cell. 2011;146:709–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham JA, Dent SY. Cross-regulation of histone modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Tate CM, You JS, Skalnik DG. Identification and characterization of the human Set1B histone H3-Lys4 methyltransferase complex. J Biol Chem. 2007a;282:13419–13428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Shukla A, Schneider J, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Florens L, Bhaumik SR, Shilatifard A. Histone crosstalk between H2B monoubiquitination and H3 methylation mediated by COMPASS. Cell. 2007b;131:1084–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee DK, Dou Y, Lee J, Lee B, Kwak E, Kong YY, Lee SK, Roeder RG, Lee JW. Coactivator as a target gene specificity determinant for histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15392–15397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607313103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997a;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Flaus AJ, Waye MM, Richmond TJ. Characterization of nucleosome core particles containing histone proteins made in bacteria. J Mol Biol. 1997b;272:301–311. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty RK, Kim J, Chatterjee C, Roeder RG, Muir TW. Chemically ubiquitylated histone H2B stimulates hDot1L-mediated intranucleosomal methylation. Nature. 2008;453:812–816. doi: 10.1038/nature06906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, Mungall AJ, Goya R, Mungall KL, Corbett RD, Johnson NA, Severson TM, Chiu R, Field M, et al. Frequent mutation of histone-modifying genes in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Nature. 2011;476:298–303. doi: 10.1038/nature10351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Kajitani T, Togo S, Masuko N, Ohdan H, Hishikawa Y, Koji T, Matsuyama T, Ikura T, Muramatsu M, et al. Deubiquitylation of histone H2A activates transcriptional initiation via trans-histone cross-talk with H3K4 di- and trimethylation. Genes Dev. 2008;22:37–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1609708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Mori T, Tada S, Krajewski W, Rozovskaia T, Wassell R, Dubois G, Mazo A, Croce CM, Canaani E. ALL-1 is a histone methyltransferase that assembles a supercomplex of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, Xu RM, Zhang Y, Struhl K. Ubiquitination of histone H2B by Rad6 is required for efficient Dot1-mediated methylation of histone H3 lysine 79. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34655–34657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osley MA. H2B ubiquitylation: the end is in sight. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1677:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Kim D, Levitan I, Dressler GR. The BRCT-domain containing protein PTIP links PAX2 to a histone H3, lysine 4 methyltransferase complex. Dev Cell. 2007;13:580–592. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robzyk K, Recht J, Osley MA. Rad6-dependent ubiquitination of histone H2B in yeast. Science. 2000;287:501–504. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazian MD, Zhang K, Grunstein M. Histone H2B ubiquitylation controls processive methylation but not monomethylation by Dot1 and Set1. Mol Cell. 2005;19:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar MP, Lyakhovich A, Visscher DW, Heng H, Kondrat N. Rad6 overexpression induces multinucleation, centrosome amplification, abnormal mitosis, aneuploidy, and transformation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2115–2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southall SM, Wong PS, Odho Z, Roe SM, Wilson JR. Structural basis for the requirement of additional factors for MLL1 SET domain activity and recognition of epigenetic marks. Mol Cell. 2009;33:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock JK, Giadrossi S, Casanova M, Brookes E, Vidal M, Koseki H, Brockdorff N, Fisher AG, Pombo A. Ring1-mediated ubiquitination of H2A restrains poised RNA polymerase II at bivalent genes in mouse ES cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1428–1435. doi: 10.1038/ncb1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun ZW, Allis CD. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature. 2002;418:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature00883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano-Prunier A, Menant A, Hobeika M, Geli V, Gwizdek C, Dargemont C. Ubiquitylation of the COMPASS component Swd2 links H2B ubiquitylation to H3K4 trimethylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/ncb1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weake VM, Workman JL. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol Cell. 2008;29:653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner M, Ruthenburg AJ. The United States of histone ubiquitylation and methylation. Molecular cell. 2011;43:5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb SJ, Fierz B, McGinty RK, Holt M, Ito T, Muir TW, Allis CD. Histone Monoubiquitylation Position Determines Specificity and Direction of Enzymatic Crosstalk with Histone Methyltransferases Dot1L and PRC2. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.361824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Zee BM, Wang Y, Garcia BA, Dou Y. The RING finger protein MSL2 in the MOF complex is an E3 ubiquitin ligase for H2B K34 and is involved in crosstalk with H3 K4 and K79 methylation. Molecular cell. 2011;43:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao T, Kao CF, Krogan NJ, Sun ZW, Greenblatt JF, Osley MA, Strahl BD. Histone H2B ubiquitylation is associated with elongating RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:637–651. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.637-651.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Takahata S, Blanksma M, McCullough L, Stillman DJ, Formosa T. yFACT induces global accessibility of nucleosomal DNA without H2A-H2B displacement. Mol Cell. 2009;35:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu BD, Hess JL, Horning SE, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Altered Hox expression and segmental identity in Mll-mutant mice. Nature. 1995;378:505–508. doi: 10.1038/378505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Zheng Y, Pham AD, Mandal SS, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Monoubiquitination of human histone H2B: the factors involved and their roles in HOX gene regulation. Mol Cell. 2005;20:601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.