Abstract

Background

Since 1983 four consecutive unified regimens: acute myeloid leukemia-Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group (AML-PPLLSG) 83, AML-PPLLSG 94, AML-PPLLSG 98 and AML-BFM 2004 Interim, for AML have been conducted by the Polish Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group (PPLLSG). In this paper, we review four successive studies on the basis of acute myeloid leukemia-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster (AML-BFM) protocol, in which a stepwise improvement of treatment outcome was observed. Treatment results of the last protocol AML-BFM 2004 Interim are presented in detail.

Methods

Three hundred and three patients with de novo AML were treated according to the AML-BFM 2004 Interim at 15 Polish centers from January 1, 2005 to June 30, 2011. A confrontation with previous treatment periods was based upon historical, already published data.

Results

In four consecutive periods, 723 children were eligible for evaluation (208, 83, 195, and 237, respectively). Complete remission rates in consecutive periods were: 71, 68, 81 and 87 %, respectively. The 5-year overall survival rates, event-free survival rates, and relapse-free survival rates were 33, 32, and 45%, respectively for AML-PPLLSG 83 regimen; 38, 36, and 53 % respectively for AML-PPLLSG 94 regimen; 53, 46, and 65 % respectively for AML-PPLLSG 98 regimen, and 63, 52, and 64 % for AML–BFM Interim 2004, respectively. Incidence of early deaths and that due to complications (mainly infections) in the first remission decreased over time from 22 to 4.6 % and from 10 to 5.9 %, respectively.

Conclusions

Despite continuous improvement in the treatment outcome, the number of failures still remains too high. Further progress seemed to be possible due to continued cooperation of oncology centers within large international study groups.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, Children, Treatment results

Introduction

In 1983, the Polish Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma Study Group (PPLLSG) introduced, for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treatment, a unified AML-PPLLSG 83 treatment protocol, which was a modified version of Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster-acute myeloid leukemia (BFM-AML) 83 protocol. Our goal was to test the feasibility of this intensive protocol in our conditions, and to develop nationwide diagnostic and treatment standards. This new protocol improved the cure rate for AML from 15 % to approximately 32 %, which was a remarkable progress, however our results were still significantly worse compared to the original acute myeloid leukemia-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster (AML-BFM ) protocol [1–4]. The lower remission rate due to a large number of early deaths was one of the main reasons for treatment failure. High number of toxicities, especially due to problems with sufficient supportive care, made us very cautious about introduction of high-dose cytarabine. Therefore, in our further protocols, we decided not to follow the AML-BFM protocol strictly (but to keep its backbone). In 1994, a modification of AML-PPLLSG 83 protocol was made: the high-risk patients (³ 5 % blasts in bone marrow on day 15 of therapy and all M5 cases) received two additional cycles with intermediate-dose cytarabine (ID-ARAC). This led to an insignificant increase in event-free survival (EFS) rate from 32 to 36 %. However, the ID-ARAC courses were not effective in producing remissions in late responders and remission rate did not increase [3, 5].

In our next AML-PPLLSG 98 protocol, we tried to develop a better and more useful stratification system. As several reports stated high activity of a new drug—idarubicin—in producing remissions we also decided to introduce it to our protocol [6–8], which resulted in better initial responses. Moreover, an increase in complete remission (CR) after induction therapy and the number of patients in standard risk group (SR) were observed. Unsatisfactory treatment outcome in the high-risk (HR) group children was mainly caused by the low remission rate [3, 9]. In 2005, by courtesy of Prof. U. Creutzig, the AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol was introduced in PPLLSG centers for further improvement of results of childhood AML treatment.

In this paper, data from the last treatment period are presented. A confrontation with previous treatment periods is based upon already published data [3, 9]. In three historical periods AML-PPLLSG 83 (1983–1993), AML-PPLLSG 94 (1994–1997), and AML-PPLLSG 98 (1998–2004), 575 children were enrolled (226, 102, 247, respectively) and 486 of them were eligible for evaluation (208, 83, 195, respectively)—Table 3. Observations for those periods were completed on March 31, 2002, for AML-PPLLSG 83 and AML-PPLLSG 94 protocols and on November 30, 2008 for AML-PPLLSG 98.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics in four AML treatment protocols in Poland

| Parameters | AML-PPLLSG 83 | AML-PPLLSG 94 | AML-PPLLSG 98 | AML-BFM 2004 Interim |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983–1994 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2004 | 2005–2011 | |

| [3] | [3] | [9] | ||

| Number of patients (N) | 208 | 83 | 195 | 237 |

| Age (years) median | 8.3 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 11.2 |

| Q1–Q3 | 4.3–15.3 | |||

| Range | 0.1–16.6 | 0.6–16.6 | 0.1–17.8 | 0.006–18.1 |

| Leukocytes (´ 103/µl) median | 12.0 | 14.7 | 17.8 | 19.4 |

| Q1–Q3 | ND | ND | ND | 6.1–58.8 |

| Range | 0.6–264 | 1.0–587 | 0.5–516 | 0.76–979 |

| Gender male/female | 106/102 | 40/43 | 105/95 | 130/107 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| CNS involvementa | 10 (4.9) | 5 (6.3) | 7 (3.6) | 29/206 (14.1) |

| Extramedullary organ involvement | 44 (21) | 16 (19) | 31 (15.9) | 60/206 (29.1) |

| FAB types | ||||

| M0 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.6) | 15 (7.7) | 21 (8.9) |

| M1 | 43 (20.7) | 12 (14.5) | 32 (16.4) | 32 (13.5) |

| M2 | 53 (25.5) | 24 (28.9) | 55 (28.2) | 66 (27.8) |

| M3 | 23 (11.1) | 9 (10.8) | 23 (11.8) | 20 (8.4) |

| M4 | 50 (24.0) | 18 (21.7) | 30 (15.4) | 48 (20.3) |

| M5 | 30 (14.4) | 11 (13.3) | 18 (9.2) | 36 (15.2) |

| M6 | 8 (3.8) | 3 (3.6) | 7 (3.6) | 3 (1.3) |

| M7 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.2) | 8 (4.1) | 10 (4.2) |

| Non defined | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.4) | 7 (3.6) | 1 (0.4) |

| Cytogenetic availablea | 0 (ND) | 54 (65) | 37 (19.0) | 176 (74) |

| t(8;21) | 2 | 3 | 26 (15) | |

| t(15;17) | 0 | 3 | 16 (9) | |

| inv(16) | 1 | 0 | 8 (4.5) | |

| Normal | 18 | 10 | 30 (17) | |

| MLL | ND | ND | 15 (8.5) | |

| Other | 11 | 21 | 81 (46) | |

| Risk groups | ||||

| SR | NA | 36 (43) | 112 (57) | 66 (27.8) |

| HR | NA | 39 (47) | 69 (36) | 171 (72.2) |

| Non qualified | NA | 8 (10) | 14 (7) | 0 (0) |

AML-BFM acute myeloid leukemia-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster, AML-PPLLSG acute myeloid leukemia-Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group, NA not applicable, ND not defined, acute myeloid leukemia

aPercentage is given for patients with data (n/total)

Elements of four consecutive treatment protocols and classification criteria for the risk groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Treatment elements of the four consecutively used treatment protocols

| AML-PPLLSG 83 | AML-PPLLSG 94 | AML-PPLLSG 98 | AML-BFM 2004 Interim |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRG and HRG | SRG and HRG | SRG and HRG | |

| 1983–1993 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2004 | |

| Induction phase | |||

| Induction ADE | Induction ADE | Induction AIE (idarubicin administered on days: 3, 4 and 5) | Induction AIE (idarubicin administered on days: 3, 5 and 7) |

| Consolidation phase | |||

| Consolidation phase 1A: 4-weeks | Consolidation phase 1A: 4 week consolidation phase: as a second element in SR and as a fourth element in HR | Consolidation phase 1A: 4-week consolidation phase: as a second element in SR and as a fourth element in HR idarubicin instead of daunorubicin |

SRG: AI chemotherapy HRG: HAM (second induction chemotherapy), AI chemotherapy |

| Consolidation phase 1B: 4 weeks | Consolidation phase 1B: Only in SRG |

Consolidation phase 1B: only in SRG |

SRG and HRG: haM |

| HRG: intermediate cytarabine doses + daunorubicin | HRG: intermediate cytarabine doses + idarubicin | ||

|

Intensification phase 1 HRG: Intermediate cytarabine doses etoposide |

Intensification phase 1 Intermediate cytarabine doses etoposide |

HAE chemotherapy | |

|

Intensification phase 2 HRG: two-week treatment with: cytarabine, 6-thioguanine and cyclophosphamide |

Intensification phase 2 HRG: two-week treatment with: cytarabine, 6-thioguanine and cyclophosphamide |

||

| Cranial irradiaton | |||

| During consolidation phase 1B doses: < 1 year = 12 Gy, 1–2 years = 15 Gy, > 2 years = 18 Gy |

SRG: timing and doses as before HRG: during intensification phase 2, doses as before |

SRG and HRG: as in previous protocol, but no irradiation in children < 1 year | SRG and HRG: parallelly to beginning of maintenance therapy, doses: < 15 months = no irradiation, 15 to < 24 months = 15 Gy, ³ 24 months = 18 Gy |

| Intrathecal treatment | |||

| During consolidation phase 1B: cytarabine on days 31, 38, 45, 51, dose adjusted to age: < 1year = 20 mg, 1–2 years = 26 mg, 2–3 years = 34 mg, > 3 years = 40 mg | SRG: cytarabine, timing and doses as before; HRG: cytarabine, timing and doses as before and additional doses during blocks: Intermediate cytarabine doses + daunorubicine, Intermediate cytarabine doses + etoposide and Intensification phase 2, day 1, 8, and 15 | SRG: as in previous protocol and additional Cytarabine dose during AIE on day 3 and 7; HRG: as in SRG during induction and consolidation 1A blocks; further treatment as in previous protocol; cytarabine doses as in previous protocols |

SRG and HRG—during chemotherapy blocks: AIE—days 1 and 8 AI—days 1 and 6 haM—days 0 and 6 HAE—day 0; HRG: additionally during HAM chemotherapy block—day 0. SRG and HRG—during maintenance treatment parallelly to CNS irradiation four times during first 4 weeks, one time per week; cytarabine doses as in previous protocols |

| Maintenance treatment | |||

| Maintenance treatment: 6-Thioguanine + cytarabine pulses, up to 2 years of total therapy | SRG: 6-thioguanine + cytarabine pulses, up to 2 years of total therapy; HRG: 6-thioguanine + cytarabine pulses, up to 1 year of total therapy | SRG: 6-thioguanine + cytarabine pulses, up to 2 years of total therapy; HRG: 6-thioguanine + cytarabine pulses, up to 1 year of total therapy | SRG and HRG: 6-thioguanine + cytarabine pulses, up to 1 year of total therapy |

| Stem cell transplantation | |||

| Not given (very limited access) | SRG and HRG: recommended but limited access | SRG: not recommended; HRG: recommended | Allogeneic HSCT from an HLA-identical sibling donor is indicated for all HRG patients, other indications—as described in present paper |

A cytarabine, AML-BFM acute myeloid leukemia-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster, AML-PPLLSG acute myeloid leukemia-Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group, D daunorubicine, E etoposide, haM intermediate cytarabine doses + mitoxanthrone, HAM high cytarabine doses + mitoxanthrone, HLA human leukocute antigen, HRG high-risk group, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, I idarubicine, M mitoxanthrone, SRG standard-risk group

Table 2.

Risk group definitions

| Study | Risk group | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| AML-PPLLSG 83 | No risk group stratification | |

| AML-PPLLSG 94 | SR | FAB other than M5 and £ 5 % blasts in BM on day 15 |

| HR GRG | M5 and £ 5 % blasts in BM on day 15 | |

| HR PRG | Any FAB and > 5 % blasts in BM on day 15 | |

| AML-PPLLSG 98 | SR | FAB other than M5 and £ 5 % blasts in BM on day 15 and no increase in blasts count after day 15 |

| HR | Patients not qualified to SR | |

| AML-BFM 2004 Interim | SR | M1/M2 with Auer rodsa,b AML with t(8;21)a,b M4Eo with inv16a,b M3 AML in Down’s syndrome |

| HR | M0 M1/M2 without Auer rods M4, M5, M6, M7 | |

AML-BFM acute myeloid leukemia-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster, AML-PPLLSG acute myeloid leukemia-Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group, GRG good response group, PRG poor response group, HR high risk, SR standard risk, FAB French–American–BritishaIn case of FLT3-ITD, the patient is reclassified to HRGbIn case of blasts are ≥ 5 % on day 15 or blastic reconstitution between day15 and 28 (modification according to PPLLSG) the patient is reclassified to HRG

Materials and methods

Three hundred and three children with de novo AML treated according to AML-BFM-2004 Interim protocol were enrolled at 15 PPLLSG centers; 237 of them were eligible for evaluation from January 2005 to June 2011. The exclusion criteria were:

AML following chronic myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome,

AML as a secondary neoplasm,

congenital malformations and severe comorbidities (including Down’s syndrome),

biphenotypic leukemia,

death before treatment,

pretreatment with other protocols or incomplete data of the patient.

The inclusion criteria were:

‘de novo’ diagnosed,

untreated AML,

absence of severe congenital malformations or comorbidities.

Data regarding children with Down’s syndrome and AML will be presented in another paper. In all children, the diagnosis was based upon bone marrow (BM) examination, including cell morphology with FAB classification, cytochemistry, and immunophenotyping. Complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, lumbar puncture, chest X-ray, echocardiography (ECG) and brain computed tomography (CT) were also performed in all children. Cytogenetic analyses (both classical and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)) were also mandatory, nevertheless, only the results from 74 % of patients were eligible. All examinations were performed in local treatment centers. Since 2005 central verification sessions of cell morphology, immunophenotyping and cytogenetic examination have been made. Moreover, since 2006 molecular studies (fusion genes AML1-ETO, PML-RARA, CBFβ-MYH11 and MLL–AF4, MLL–AF9, MLL–ENL, as well as FLT3-ITD and WT1 overexpression) have also been performed in Genetic Laboratory of the University Children’s Hospital of Krakow.

Elements of AML-BFM 2004 Interim treatment protocol and classification criteria for risk groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2. According to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) from HLA-identical sibling donor was indicated in all patients of the HR group in the first remission. Children with blasts after the second induction (HAM) or still in aplasia 4 weeks after second induction were qualified for allo-HSCT from an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical unrelated donor.

Supportive care guidelines include the use of prophylactic antifungal medication and co-trimoxazole/trimethoprim against Pneumocystis jiroveci n all patients. We do not use hematopoietic growth factors (such as G-CSF) or antibiotics routinely as a prophylaxis regimen.

Treatment toxicity analysis was not performed because of insufficient data received by the time of preparation of this paper. Patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Complete remission was defined as no more than 5 % of blasts in BM demonstrating normal or only slightly decreased cellularity with signs of regeneration of normal hematopoiesis, regeneration of normal cell production in peripheral blood, lack of blasts in peripheral blood and disappearance of any extramedullary sites.

Treatment failures classified according to criteria proposed by Creutzig et al. [10], included:

Early death—defined as death during the first 42 days from the start of the treatment.

Death in continuous CR—treatment related mortality (TRM), including death after HSCT in the first CR.

Nonresponder—defined as a lack of CR during 6 weeks since the start of the treatment.

Relapses.

For patients who completed consolidation while still having active disease, second-line protocols were recommended.

The results were expressed by means of remission rates, EFS, overall survival (OS), and relapse-free survival (RFS). Survival rates were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. For statistical analyses, STATISTICA, version 10, StatSoft Inc. (2011) software packages were used. The observation was completed on November 30, 2011.

Results of treatment

Treatment results are presented in Tables 4–5 and Figs. 1–7.

Table 4.

Treatment results of patients according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol compared to earlier studies in Poland

| Parameters | AML-PPLLSG 83 | AML-PPLLSG 94 | AML-PPLLSG 98 | AML-BFM 2004 INTERIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983–1994 | 1994–1997 | 1998–2004 | 2005–2011 | |

| [3] | [3] | [9] | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%)e | N (%) | |

| No. of patients | 208 | 83 | 195 | 237 |

| Early death | 46 (22.1) | 12 (15.1) | 16 (8.0) | 11, including in M3-3 and M5-4 (4.2) |

| Blasts day 15 ³ 5 %a | ND | 34/72 (47.2 | 47/182 (25.6 | 56/216 (25.9) |

| Nonresponders | 13 (5.7) | 15 (18.0) | 20 (10.3) | 19 (8.5) |

| CR achieved | 150 (71.4) | 56 (67.5) | 159 (82.0) | 207 (87.3) |

| Death in CCR (including death after SCT in first CR)b | 20 (0) (9.6) | 9 (3) (10.8) | 18 (5) (9.2) | 14 (3) (5.9) |

| Relapse (cumulative incidence) | ND | ND | ND | 36.4 ± 3.7 |

| Secondary malignancies | ND | ND | ND | 0 (0) |

|

Total group pSurvival (5 years) |

33 ± 3 | 38 ± 5 | 53 ± 5 | 63.1 ± 3.3 |

|

Total group pEFS (5 years) |

32 ± 3 | 36 ± 5 | 47 ± 5 | 51.8 ± 3.4 |

| SR pEFS (5 years) | NA | 37 ± 8 | 62 ± 7 | 55.0 ± 6.6 |

| HR pEFS (5 years) | NA | 41 ± 8 | 33 ± 7 | 50.6 ± 4.0 |

AML-BFM acute myeloid leukemia-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster, AML-PPLLSG acute myeloid leukemia-Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group, CR complete remission, CCR continous complete remission, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, NA not applicable, ND non definedaPercentage is given for patients with data (n/total)bThe values in second parenthesis denotes percentage

Table 5.

Treatment results according to presented features in all children treated in AML-BFM 2004 Interim study

| Factors | No. of total patients | Overall survival ± SE (%) | Event-free survival ± SE (%) | No. of patients with achieved CR (%) | Relapse-free survival ± SE (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 year | p-value | 5 year | p-value | 5 year | p-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 130 | 63.9 ± 4.5 | 0.59 | 54.6 ± 4.6 | 0.24 | 119 | 62.5 ± 4.8 | 0.51 |

| Female | 107 | 62.1 ± 4.9 | 48.5 ± 5.1 | 88 | 65.3 ± 5.8 | |||

| Age at diagnosis (year) | ||||||||

| < 2 | 40 | 57.4 ± 7.8 | 0.47 | 45.7 ± 8.2 | 0.46 | 36 | 58.2 ± 9.2 | 0.36 |

| 2–10 | 62 | 68.5 ± 6.2 | 50.4 ± 6.6 | 53 | 63.7 ± 7.1 | |||

| > 10 | 135 | 62.5 ± 4.5 | 54.3 ± 4.6 | 118 | 65.3 ± 4.9 | |||

| WBC ´ 109 | ||||||||

| < 20 | 121 | 68.6 ± 4.5 | 0.31 | 62.3 ± 4.6 | 0.026 | 110 | 75.9 ± 4.6 | 0.003 |

| 20–100 | 75 | 56.8 ± 6.1 | 40.8 ± 6.2 | 63 | 50.2 ± 7.0 | |||

| > 100 | 41 | 58.4 ± 8.0 | 40.9 ± 8.1 | 34 | 50.6 ± 9.4 | |||

| FAB type | ||||||||

| M0 | 21 | 66.9 ± 11.4 | 0.07 | 63.5 ± 11.3 | 0.16 | 18 | 67.9 ± 12.1 | 0.09 |

| M1 | 32 | 63.3 ± 9.6 | 55.4 ± 9.5 | 28 | 65.2 ± 10.2 | |||

| M2 | 66 | 68.7 ± 6.1 | 52.2 ± 6.3 | 62 | 61.3 ± 6.7 | |||

| M3 | 20 | 74.6 ± 9.8 | 64.0 ± 12.9 | 16 | 82.9 ± 11.3 | |||

| M4 | 48 | 66.2 ± 6.9 | 52.6 ± 7.4 | 43 | 65.6 ± 7.8 | |||

| M5 | 36 | 43.9 ± 8.7 | 31.3 ± 8.4 | 29 | 42.9 ± 10.6 | |||

| M6 + M7 | 14 | 53.8 ± 13.8 | 53.8 ± 13.8 | 11 | 88.9 ± 10.4 | |||

The values in italics denotes close statistical significance

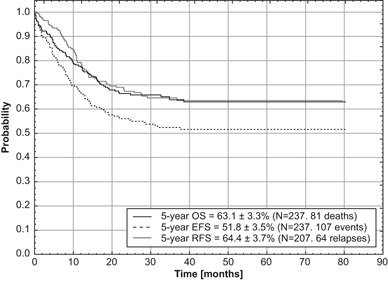

Fig. 1.

Overall survival (OS), event-free survival (EFS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) for a total group of children with acute myeloid leukemia treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

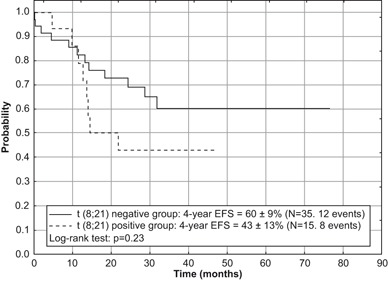

Fig. 7.

Event-free survival (EFS) for children in SR group of acute myeloid leukemia with and without the presence of t(8;21) treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

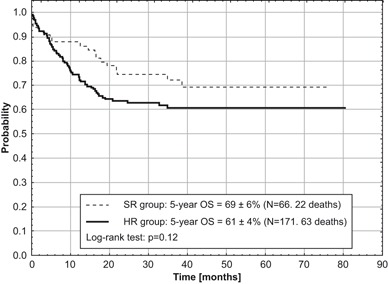

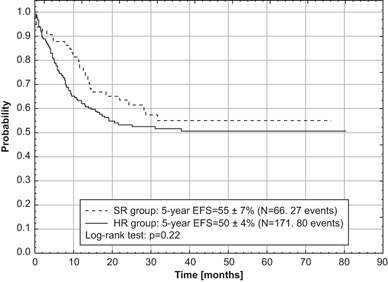

Out of 237 children eligible for evaluation, treated according to AML-BFM Interim 2004, 66 (28 %) were stratified into SR group and 171 (72 %) into HR group. CR was achieved in 207 (88 %) children. Eighty-one children died, 11 before day 42 of the induction therapy (early deaths) and 14 children in remission (3 patients after allo-HCST). Ten CR patients died because of severe infections and one died from CNS toxicity that developed probably after cytarabine. Results of BM aspiration biopsy done on day 15 were available in 216 children with 56 (26 %) demonstrating more than 5 % of blasts in BM. Five year OS, EFS, and RFS for all evaluated children were 63 ± 3, 52 ± 3 and 64 ± 4 %, respectively (Fig. 1). OS and EFS rates were comparable in both risk groups (SR: 69 ± 6 and 55 ± 7 %, respectively, HR: 61 ± 4 and 50 ± 4 %, respectively). However, neither of those results were statistically significant (Figs. 2 and 3). In patients who eventually relapsed, CR lasted from 0.86–46.7 months (median: 10.5 months).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (OS) for two risk groups of children with acute myeloid leukemia treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

Fig. 3.

Even-free survival (EFS) for two risk groups of children with acute myeloid leukemia treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

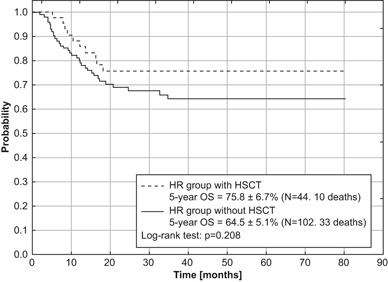

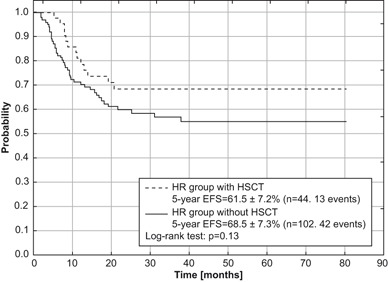

For the entire evaluated group, significant impact of initial WBC count on treatment outcome (EFS and RFS) was demonstrated (p = 0.026 and 0.003, respectively). WBC count is defined as high if it is ³ 20 ´ 109/L, and low if < 20 ´ 109/L. The highest rates of 5-year EFS and RFS were achieved for children with initial WBC count < 20 ´ 109/L. For the entire analyzed group (Table 5), the correlation between types of FAB and OS was close to statistical significance (p = 0.07), and the worst outcome was demonstrated for M5 type (OS = 44 ± 9 %). In the HR group the statistical analysis revealed a significant impact of initial WBC count on RFS (p = 0.021). The highest rate of RFS was seen in children with an initial WBC count of < 20 ´ 109/L. There was no significant impact of FAB types on survival rates in the HR group, however the lowest rates were obtained for M5 type (OS = 43.9 ± 8.7, EFS = 31.3 ± 8.4, RFS = 42.9 ± 10.5). Among 171 children stratified into HR group, HSCT in the first CR was performed in 44. Higher survival rates in these patients were observed in comparison with patients from the HR group without HSCT (Figs. 4 and 5 ). The differences were not statistically significant.

Fig. 4.

Overall survival (OS) for HR group with and without HSCT in first remission treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

Fig. 5.

Event-free survival (EFS) for HR group with and without HSCT in first remission treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

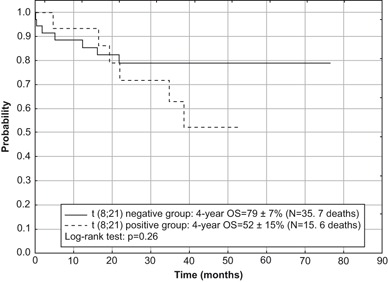

None of the analyzed factors had relevant influence on the survival rates in the SR group. The worse outcome was in patients with translocation t(8;21) (OS = 46 ± 14 %, EFS = 43 ± 13 %, RFS = 46 ± 14 %) in comparison with patients without translocation (OS = 66 ± 9 %, EFS = 60 ± 9 %, RFS = 66 ± 9 %), although differences were not statistically significant (Figs. 6 and 7). In the SR group without t(8;21) only one patient demonstrated an inv(16).

Fig. 6.

Overall survival (OS) for children in SR group of acute myeloid leukemia with and without the presence of t(8;21) treated according to AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol in Poland

Discussion

Since 1983, PPLLSG has introduced four consecutive unified protocols for the treatment of AML: AML-PPLLSG 83, AML-PPLLSG 94, AML-PPLLSG 98, and AML-BFM 2004 Interim. Therapies based on AML-BFM protocols have led to a gradual increase of the 5-year EFS from less than 15 % before 1983, to 52 % after 2004 (Table 4). Within the last 25 years we observed a progressive increase of OS from 33 to 65 %. Treatment failure rates have decreased gradually, but still remain our major concern. Total early deaths decreased from 22 % in the first period to 4.2 % in the fourth period. Deaths in remission decreased from 10 % in the first and the second period to 5.9 % in a current protocol. Number of non-responders increased between the first and the second period from 6 to 18 %, and then decreased to 8.5 % at present. Observed reductions of early death and treatment-related mortality were achieved by intensification of antileukemic treatment and improvement in supportive care, which also shown in other publications [10–14]. Experience accumulated for over 30 years of using AML-BFM protocols was also of importance.

Some researches in childhood AML have identified several prognostic factors. Nowadays genetic abnormalities and response to treatment are considered the most relevant factors [14–16]. Significance of other factors, such as age, WBC, and FAB type has been not clearly verified yet [17, 18]. In our study, statistical analysis of all patients revealed that differences for both RFS and EFS were significant depending on the initial WBC count and close to statistical significance for the FAB type (Table 5). We also found statistically significant difference in RFS for HR patients depending on the initial WBC (p = 0.021). Thus, more detailed analyses are planned to identify the exact initial leukocyte count and FAB type responsible for a higher risk of treatment failures.

Since 1989, the HSCT has become available in our country, but access to this procedure was very limited till the late 1990s. In AML-BFM 2004 Interim protocol we perform allo-HSCT in patients with unfavorable risk factors. However, the benefit of allo-HSCT as a post-remission consolidation treatment in the first remission of AML in children remains controversial. The significantly lower relapse rate after allo-HSCT is not always followed by improvement of survival [19–23]. In our study, 3 children out of 44 with allo-HSCT in first CR had died because of treatment-related death.

About 80–90 % of children with AML achieve CR with current protocols, although in around 30 % of them there is eventually a relapse [10–14]. Results of therapy for recurrent AML remain poor [24, 25]. We are concerned about the high event rate in children from the SR group (Fig. 3). In this group, lower survival rates were found in patients with translocation t(8;21) in comparison with children without this genetic rearrangement (Figs. 6 and 7), which is consistent with other studies [16]. This observation underlies the upcoming proposal of the AML-BFM Study Group for AML with t(8;21), which involves augmentation of induction therapy by introduction of the HAM cycle.

The treatment of pediatric AML needs further improvement. Studies on biology of AML are needed to explore genetic abnormalities, which could be aimed for new targeted therapies [15, 26–28]. Introduction of targeted treatment modalities could allow a better stratification of patients, and use of more individualized therapies may lead to further improvements of treatment outcomes. The new treatment protocols for children with AML are expected to improve the treatment results and decrease the late side effect rates [13, 14, 29, 30]. However, further progress in AML therapy seems possible because of continued cooperation of oncology centers within large international study groups.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no actual and potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Cyklis R, Armata J, Dluzniewska A. Preliminary evaluation of the results of treatment of myeloblastic leukemia using the AML-BFM-83 protocol based on data from the Polish group for the treatment of leukemia in children. Pol Tyg Lek. 1988;43:376–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cyklis R, Dluzniewska A, Armata J. Efficacy of AML-BFM-83 regimen in children with acute myeloblastic leukemia. Over 10 year experience of Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group. Acta Hematol Pol. 1996;27:131–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dluzniewska A, Balwierz W, Armata J. Twenty years of Polish experience with three consecutive protocols for treatment of childhood acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:2117–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creutzig U, Ritter J, Schellong G. Identification of two risk groups in childhood acute myelogenous leukemia after therapy intensification in the study AML-BFM-83 as compared with study AML BFM-78. Blood. 1990;75:1932–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dluzniewska A, Balwierz W, Moryl-Bujakowska A. Intermediate doses of cytarabine arabinoside in the treatment of acute non-lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Med Wieku Rozw. 2000;4:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creutzig U, Ritter J, Zimmermann M, for the AML-BFM Study Group Idarubicin improves blast cell clearance during induction therapy in children with AML: results of study AML-BFM 93. Leukemia. 2001;15:348–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiffers J, Huguet F, Stoppa AM. A prospective randomized trial of idarubicin vs daunorubicin in combination chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia of the age group 55–75. Leukemia. 1996;10:389–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells RJ, Arndt CA. New agents for treatment of children with acute myelogenous leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1995;17:225–33. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199508000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dluzniewska A, Balwierz W, Balcerska A. Treatment failure in children with acute myelocytic leukemia: over 25-year experience of Polish pediatric leukemia/lymphoma study group with four consecutive unified treatment protocols for children with acute myelocytic leukemia. Przegl Lek. 2010;67:366–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Reinhardt D. Early deaths and treatment-related mortality in children undergoing therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: analysis of the multicenter clinical trials AML-BFM 93 and AML-BFM 98 . 2004;22:4384–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrahamsson J, Forestier E, Heldrup J. Response-guided induction therapy in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with excellent remission rate. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29:310–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson BES, Webb DKH, Howman AJ. Results of a randomized trial in children with acute myeloid leukaemia: medical research council AML12 trial. Br J Haematol. 2011;155:366–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jastaniah W, Abrar MB, Khattab TM. Improved outcome in pediatric AML due to augmented supportive care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;10:1–3. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaspers GLJ, Zwaan CM. Pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: towards high-quality cure of all patients. Haematologica. 2007;92:1519–32. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coenen EA, Raimondi SC, Harbott J. Prognostic significance of additional cytogenetic aberrations in 733 de novo pediatric 11Q23/MLL-rearranged AML patients: results of an international study. Blood. 2011;117:7102–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-328302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creutzig U, Zimmermann M, Bourquin JP. Second induction with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone: different impact on pediatric AML patients with t(8;21) and with inv(16) Blood. 2011;118:5409–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-364661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creutzig U, Buchner T, Sauerland MC. Significance of age in acute myeloid leukemia patients younger than 30 years. Cancer. 2008;112(3):562–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubnitz JE, Pounds S, Cao X, et al. Treatment outcome in older patients with childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Horan JT, Alonzo TA, Lyman GH. Impact of disease risk on efficacy of matched related bone marrow transplantation for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5797–801. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klingebiel T, Reinhardt D, Bader P. Place of HSCT in treatment of childhood AML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(S):S7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klusmann JH, Reinhardt D, Zimmermann M. The role of matched sibling donor allogeneic stem cell transplantation in pediatric high-risk acute myeloid leukemia: results from the AML-BFM 98 study. Haematologica. 2012;97:21–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.051714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, Hassebroek A. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adolescent and young adults compared with children and older adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:861–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niewerth D, Creutzig U, Bierings MB. A review on allogeneic stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:2205–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorman MF, Ji L, Ko RH. Outcome for children treated for relapsed or refractory acute myelogenous leukemia (rAML): a therapeutic advance in childhood leukemia (TACL) consortium study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:421–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sander A, Zimmermann M, Dworzak M. Consequent and intensified relapse therapy improved survival in pediatric AML: results of relapse treatment in 379 patients of three consecutive AML-BFM trials. Leukemia. 2010;24:1422–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balwierz W, Pietrzyk JJ, Wator G. Genotyping and minimal residual disease study in children with acute myeloid leukemia: preliminary results. Przegl Lek. 2010;67:371–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange BJ, Yang RK, Gan J. Soluble interleukin-2 receptor. Activation in children’s oncology group randomized trial of interleukin-2 therapy for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:398–405. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Dahl G. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: results of the AML02 multi center trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:543–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molgaard-Hansen L, Glosli H, Jahnukainen K. Quality of health in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia treated with chemotherapy only: a NOPHO-AML study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1222–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultz KA, Chen L, Chen Z. Health and risk behaviors in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:157–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]