Abstract

Polycyclic xanthone natural products are a family of polyketides which are characterized by highly oxygenated, angular hexacyclic frameworks. In the last decade, this novel class of molecules has attracted noticeable attention from the synthetic and biological communities due to emerging reports of their potential use as antitumour agents. The aim of this article is to highlight the most recent developments of this subset of the xanthone family by detailing the innate challenges of the construction of this class of natural products, new synthetic approaches, and pharmacological data.

Introduction

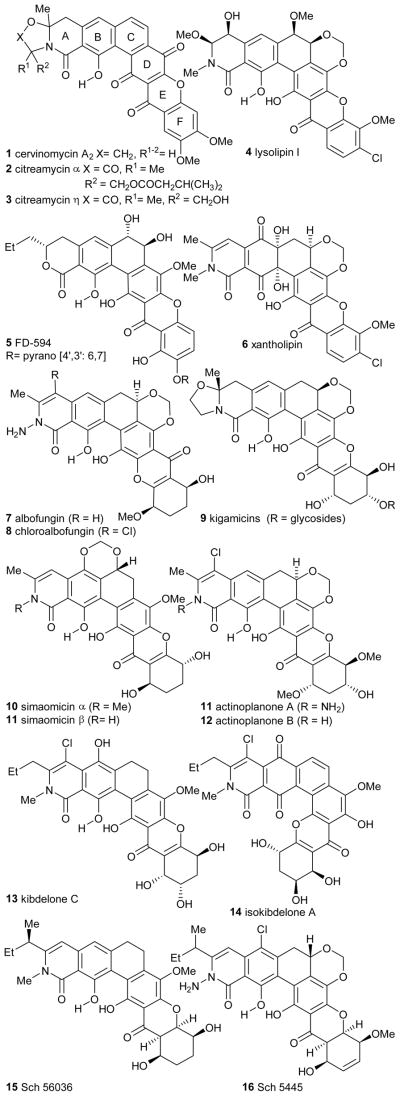

Polycyclic xanthone natural products are a family of polyketides which are characterized by their highly oxygenated angular hexacyclic frameworks (Figure 1). Since the isolation of the first member of this family albofungin1 (7) over forty years ago, this class of molecules has intrigued numerous research groups not only for their unique chemical structures but also their diverse biological activities.1–12 Initially, interest in the polycyclic xanthones was related to their antimicrobial/anticoccidial1–6 activities, as many members showed strong activity towards Gram-positive bacteria. In the last decade, there has been a noticeable increase in reports on both synthetic and pharmacological investigations of this novel class of molecules. This is due to the emerging significance of xanthone and tetrahydroxanthone-containing natural products such as simaomicin α2 (10), kigamycin C8 (9), and kidelones A-C10 (13, 24, 27) as antiproliferative agents.

Figure 1.

Structures of isolated polycyclic xanthones.

Although there have been many reviews13 on xanthone natural products which describe the structural, biochemical, and medicinal properties of this broad family of natural products, there has of yet been an article which consolidates chemistry, new synthetic approaches, and pharmacological data of this smaller subset of the xanthone family. The purpose of this review is to provide an informative overview of these topics and to serve as a point of reference for the advancement of drug discovery, pharmacology, and synthetic approaches towards this novel class of molecules. This article will also focus on the lessons learned from the both the synthetic and biological communities and where the future challenges lie ahead for this family of natural products.

Structure

Polycyclic xanthones are a smaller subset of the xanthone family which possess a highly oxygenated hexacyclic skeleton and typically a cyclic amide which is rare amongst aromatic polyketides.9b Key variations of these molecules include various substituents on the amide nitrogen (e.g. 11–12), the unique B ring quinone/hydroquinone oxidation state as found in the kibdelones/isokibdelones series (e.g. 13–14), saturated or substituted C rings, and variation in the oxidation state in the F-ring which is part of the characteristic xanthone moiety itself (Figure 1). The oxidation state of the xanthone ring can be further subdivided into fully aromatic-, tetrahydro-, and hexahydro-xanthone derivatives (e.g. 1–6, 7–14 and 15–16).

The structures of many of the members of the class were determined by single X-ray crystal structure or analysis of 1D and 2D NMR spectra. In many cases, only the relative stereochemistry was assigned and therefore the absolute stereochemistry required confirmation through chemical synthesis. This was such the case for kibdelone C and led to the total synthesis of the natural enantiomer (+)-kibdelone C by the Porco group14 and (−)-kibdelone C by the Ready group.15 For polycyclic xanthones, it is difficult to predict the absolute stereochemistry of certain chiral centers on the hexacyclic structure since there has been limited reports describing synthetic efforts towards such members of the family (see Synthesis section) and the installation of such centers likely occurs biosynthetically at a late stage.

Numerous biosynthetic studies and isotope-labelling feeding experiments on polycyclic xanthones including the citreamycins (2, 3),6c simaomicin α (10),2b lysolipin I (4),4e FD-594 (5),12b and xantholipin (6)9b have revealed that this family of natural products are derived from a single polyketide chain. Multiple post-polyketide synthesis (PKS) modifications of this chain produce the variety of polycyclic xanthones that are observed in nature. Studies on the isolation and sequencing of the gene cluster of lysolipin I (4)4f suggested that the biosynthetic origin of the xanthone was derived from a “Baeyer-Villiger” type oxidation of a quinone ring. A similar study on FD-594 (5) suggested rather an epoxidation followed by a Baeyer-Villiger oxidation was involved in the formation of the xanthone ring.16

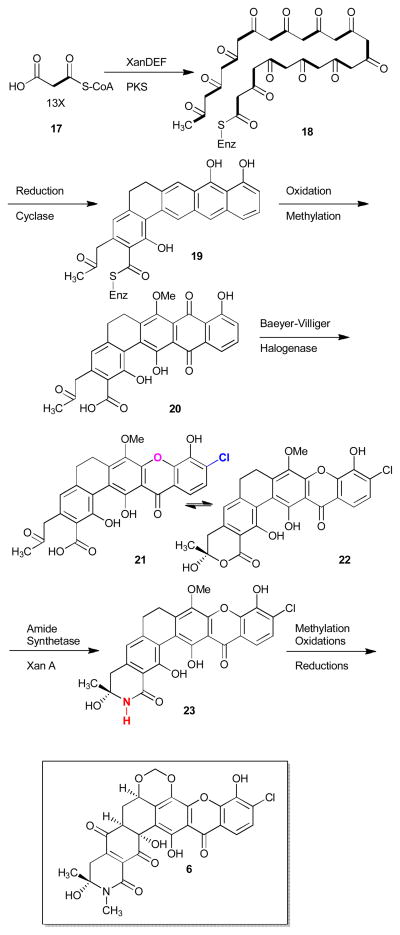

A recent report by You and coworkers9b identified the precise FAD binding post-PKS monoxygenase involved in the Baeyer-Villiger approach to the xanthone ring formation process and various key tailoring steps utilized in polycyclic xanthone biosynthesis such as late amide bond formation via an amide synthetase (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Biosynthesis of xantholipin (6).

The chiral centers of the B/C rings of xantholipin are thought to be derived from enzymatic reduction and oxidation of these rings at the completion of its biosynthesis. The characterization of the biosynthetic pathway of xantholipin allowed not only the understanding of unusual modifications involved in the biosynthesis of polycyclic xanthones but also identified key features of its structure related to its antitumour activity (see Biological Activity section).

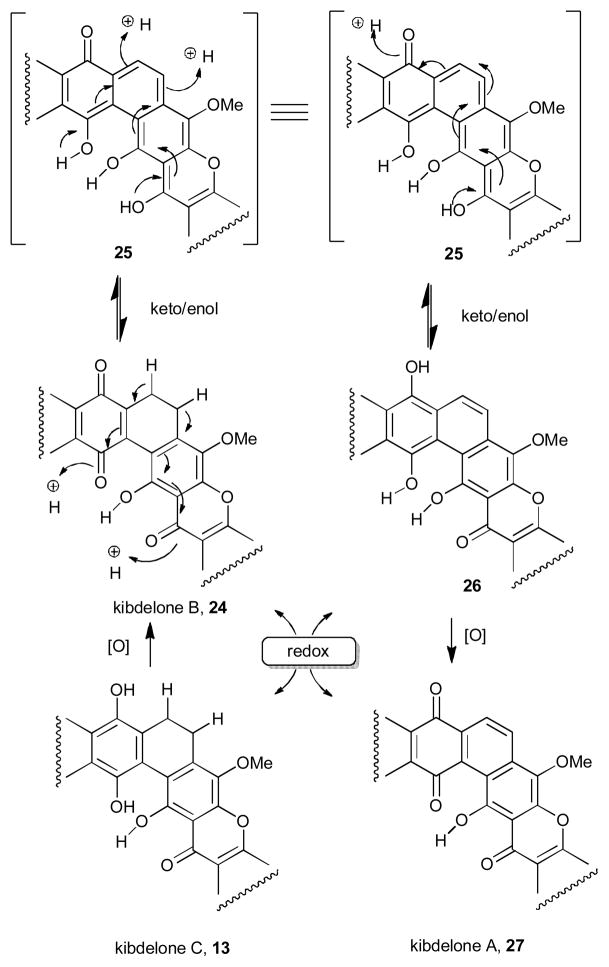

Unique intrinsic structural aspects of certain polycyclic xanthone were also discovered during their characterization. For example, kibdelones B-C and their congeners the isokibdelones B-C (e.g. 13–14), isolated by Capon and co-workers from the rare Australian Kibdelosporangium sp., are known to equilibrate to a mixture of kibdelones A-C (13, 24, 27) under mild conditions (40 °C in MeOH).10–11 It was rationalized that such a mixture could arise through aerobic oxidation, hydroquinone/quinone redox transformations, and methanol-promoted ketoenol tautomerizations using a highly reactive quinone methide (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Equilibration of kibdelone A-C.

There is no evidence given by the authors of any equilibration of the kibdelones to the isokibdelones as the two are thought to arise from an altered biosynthetic sequence. An additional example of a unique structural property is that of FD-594 (5, Figure 1). This natural product possesses solvent-dependent atropisomerism depending on the conformation adopted by the hydroxyls on the C-ring and therefore gives opposite CD-spectra depending on the solvent.17 In chloroform, the hydroxyls on the C ring adopt an equatorial relationship while in methanol or water they adopted a diaxial relationship. It was therefore thought that this difference in conformation gives rise to the observed difference in circular dichroism and could also have biological relevance.

Biological Activity

This class of natural products initially attracted interest in the area of antimicrobial/anticoccidial biological activity, since most members showed strong activity towards Gram-positive bacteria1–6 including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureas and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis.3,8,18 For example, simaomicin α (10), was found to be one of the most potent non-synthetic broad spectrum anticoccidial agents ever reported, requiring just 1 ppm in the diet of chickens.2 Other polycyclic xanthones such as lysolipin I (4) have been shown to inhibit cell-wall biosynthesis and therefore are active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.4a

Recently, there have been numerous reports of polycyclic xanthones showing a wide array of biological activities ranging from potent antifungal activity (Sch 5445, (16))19 to heat shock protein inhibition (xantholipin, (6)).9a Simaomic in α (10), isolated from the culture broth of Actinomadura madurae ssp. simaoensis, was originally reported as an antibiotic and anticoccidial agent.2 In 2009, Koizumi and collaborators showed that nanomolar concentrations of simaomicin α (10) could inhibit the G1 phase of the cell cycle, leading to apoptotic cell death in human tumour cell lines.2 Similarly, FD-594 (5), an antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces sp. TA-0256, was found to both inhibit certain Gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureas 209-Pj, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Bacillus subtilis ATCC 633, and a variety of tumour cell lines (HL-60, P388, L1210, HeLa, A549) with an IC50 which is in the μg/mL range.12

Xantholipin (6) produced by Streptomyces flavogriseus is an antibiotic which was reported in 2002 to have potent cytotoxicity against the leukemia cell line HL60 (IC50 < 0.3 μm) and the oral squamous carcinoma cell line KB (IC50 < 2 nm).9b It was also found to inhibit gene expression of heat shock protein HSP47 which are related to a variety of fibrotic diseases with an IC50 of 0.20 μm.9a In 2012, You and coworkers cloned and sequenced the entire gene cluster of xantholipin (6)9b in order to identify both the biosynthetic pathway and the key structural features related to tumour proliferation inhibition (Scheme 1). They tested xantholipin (6), 20, 21, and doxorubicin, a common anticancer drug, in in vitro cytotoxicity assays. They discovered that 6 was more effective than doxorubicin against lung cancer cell lines (10-fold), colon cancer cell lines (3-fold) and equally as effective against leukemia cell lines. On the other hand, precursors 20 and 21 which do not possess post-PKS modifications such as amide bond and stereogenic centers on the B/C rings were 102- to 103-fold less active. This indicates that such key structural features play an important role in bioactivity.

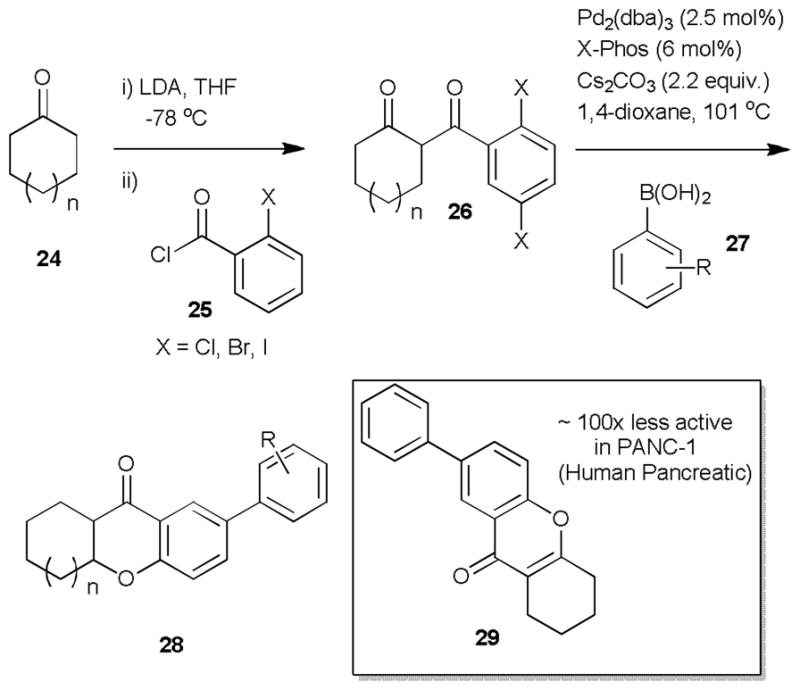

Interestingly, in 2011 Shipman and collaborators20 studied the importance of the 7-substituted tetrahydroxanthone pharmacophore for the biological activity of the kigamicins (9) and other related xanthones such as kibdelones A-C (13, 24, 27), simaomicin α (10), and puniceaside B.21 The kigamicins (9),8 isolated from the culture broth of Amycolatopsis sp. ML630-mF1, have shown significant anticancer properties and have even progressed to human tumour xenograft studies where they showed promising activity towards xenograft models of pancreatic tumours. For their study, Shipman and coworkers synthesized a variety of simplified 7-substituted tetrahydroxanthone using palladium-catalysis to both construct the tetrahydroxanthone ring and introduce substitution at C-7 from simple bromoketone precursors (26) (Scheme 3).20

Scheme 3.

Shipman synthesis of simplified xanthones.

The diketone precursors (26) were constructed using an analogous transformation to Watanabe’s tetrahydroxanthone synthesis using lithium enolates.22 Treatment of diketone 26 with palladium (0), Xphos ligand, and phenyl boronic acids (27) under basic conditions provided tetrahydroxanthones 28 in high yield (60–85%). They then proceeded to establish if the simplified version of the kigamycin pharmacophore, the C-7 substituted tetrahydroxanthones (28), retained antitumour activity against human pancreatic cancer cells (PANC-1) grown in nutrient deprived conditions rather than cells grown in nutrient rich media (“anti-austerity” stategy).23 Since cancer cell tolerance to nutrient-deprived conditions might be an important sign of malignancy, a preferred inhibition of cells in such deprived conditions can be a sign of a novel antitumour property. When comparing synthetic compound 29 to commercially sourced kigamicin C, assays displayed that 29 conserved the “anti-austerity” effect by therefore inhibiting nutrient deprived cancer cell lines 10-times more than nutrient rich cancer cells, but was noticeably less active than kigamicin C (>100 fold). Therefore, the minimum pharmacophore related to these types of polycyclic xanthones necessary to keep activity was thought to be 7-aryl tetrahydroxanthone (28).

Kibdelones A-C (13, 24, 27), isolated by Capon and coworkers in 2007, displayed selective cytotoxicity against a panel of human tumour cell lines and have significant antibacterial and nematocidal activity. 10 Kibdelone C (13), for example, has a GI50 of < 1 nm against a SR (leukemia) tumour cell line and SN12C (renal) cell carcinoma, on the other hand their congeners, the isokibdelones A-C (e.g. 14), were found to be 10 to 200 fold less potent against a variety of tumour cell lines (e.g. isokibdelone A (14) NCI 60 cell-line mean GI50= 30 nM). These two series of natural products possess a common ABCD core with their respective analogs (e.g kibdelone A/isokibdelone A) and diverge in their connectivity to the EF ring (13–14).

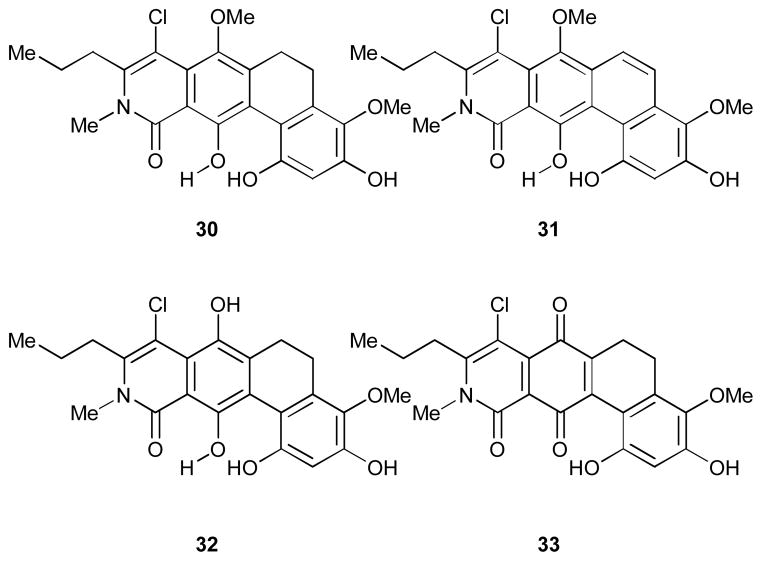

During the course of total synthesis of (+)-kibdelone C,14 the Porco group submitted ABCD core structures of these natural products with varying oxidation states and substitution on the B ring (Figure 2) to the NCI 60-cell screen to evaluate its relevance to the biological activity. The NCI 60-cell screen has cell-lines from the nine distinct tumour types: leukemia, colon, lung, CNS, renal, melanoma, ovarian, breast, and prostate.24 Compounds 30 and 31 were judged to be inactive, with mean cell growth of 82% and 93% of control at 10 μM, respectively. Compounds 32 and 33 passed the criteria for testing in dose-response format, with mean cell growth of 63% and 54%, respectively. In dose-response format, both 32 and 33 bearing the ABCD functionalities of kibdelones/isokibdelone B and C respectively showed mean GI50 values of 4.5 μM, while having no selectivity. The contribution of the E and F rings of these polycyclic xanthone structures are therefore thought to be highly important for biological activity.

Figure 2.

ABCD ring fragments of the kibdelone and isokibdelone submitted to NCI 60-cell lines screening.

Based on the Shipman,20 Porco,14 and You9b structure activity relationship studies, key factors in polycyclic xanthone biological activity are likely related to both the xanthone moiety and the stereogenic centers on the core of the natural products rather than the polyketide framework. Future investigations on simplified fragments of these natural products are necessary to ascertain both the key features related to activity and the mode of action of these natural products.

Synthesis

Prior to 2011, the total synthesis of polycyclic xanthone natural products was limited to fully aromatized targets such as cervinomycin A1 and A2 (1).5d–h Reports of fragment synthesis were also present in the literature for lysolipin I (4)4c and Sch 56036 (15).9b The lack of synthetic reports was potentially due to the more challenging partially saturated polycyclic xanthones for which reliable methods for their construction holds greater challenge.13d

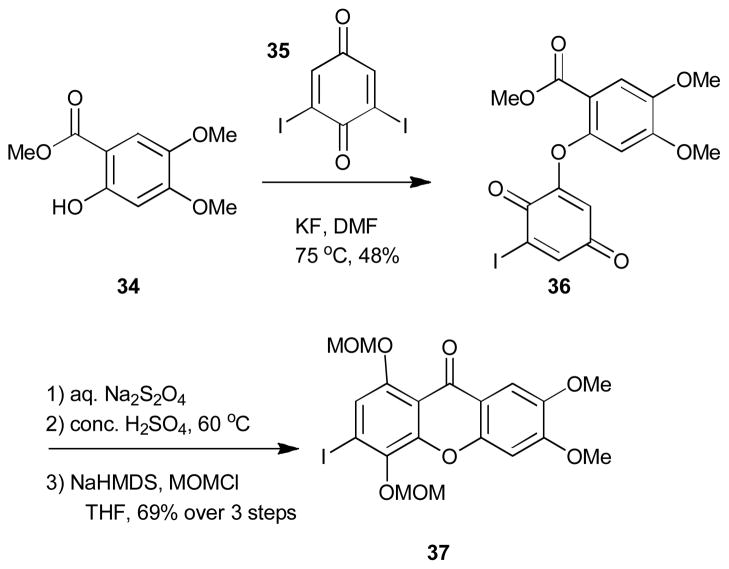

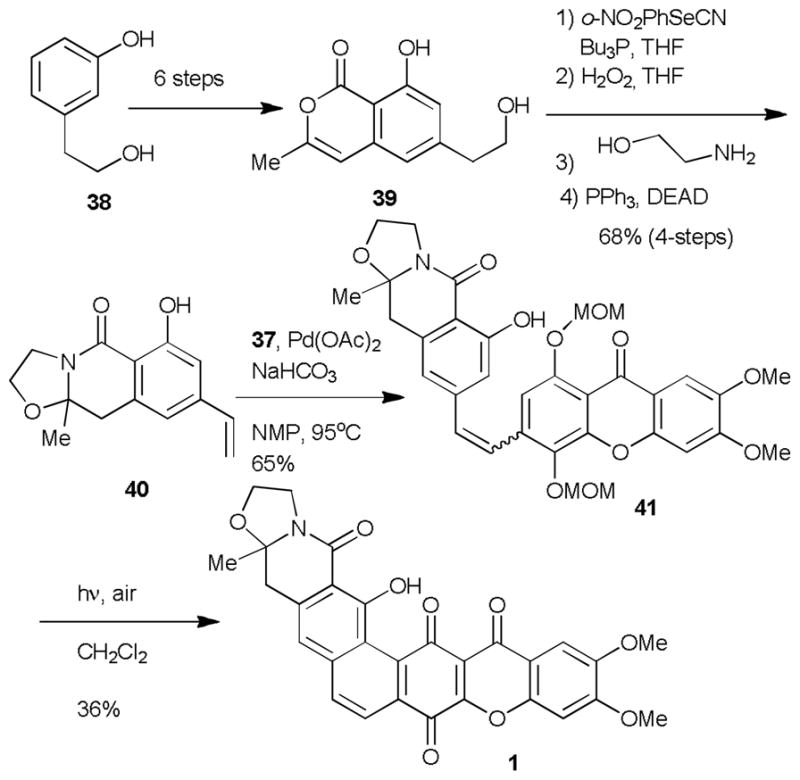

The first total synthesis of cervinomycin A1 and A2 (1) was completed in 1989 by Kelly and is a benchmark approach towards this family of natural products.5d A convergent approached was utilized, where the EFG (37, Scheme 4) and AB (40, Scheme 5) rings were independently synthesized then combined one bond at a time to close down the hexacyclic core of the molecule. The Kelly synthesis was the first hexacyclic xanthone synthesis and utilized an efficient strategy for xanthone formation previously reported by Brassard and coworkers (Scheme 4).25

Scheme 4.

Kelly’s Synthesis of the Xanthone Fragment of cervinomycin A2.

Scheme 5.

Kelly’s Synthesis of the cervinomycin A2.

Synthesis of the requisite AB fragment (40) began by transformation of phenol 38 in six steps to isocoumarin 39. The styrene moiety was then installed in a two-step selenide formation/oxidation sequence and the requisite oxazolidine ring was installed by treatment of isocoumarin 39 with ethanolamine followed Mitsunobu cyclodehydration. The synthesis was then highlighted by an intermolecular Heck reaction between styrene 40 and xanthone 37 followed by photocyclization which provided the fully oxidized ring system of 1 in modest yields. Other approaches by Mehta,5b,e Rao,5f and coworkers towards these targets have also been reported and employ a related two fragment strategy used by Kelly.

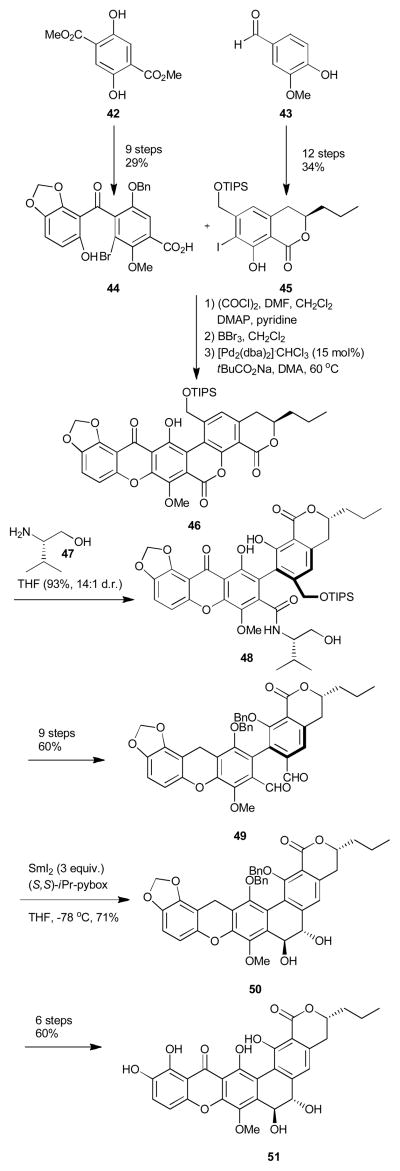

In 2009, Suzuki and coworkers published the stereoselective synthesis of FD-594 aglycon (51, Scheme 6).12c This was the first synthesis of a member of the polycyclic xanthones that contained chirality on its hexacyclic framework. The synthesis was highlighted by a chirality transfer strategy utilizing axially chiral biaryl 49 (Scheme 6). To construct this key intermediate, both the DEF (44) and AB fragments (45) were first independently synthesized and assembled into lactone 46 one bond at a time first through the acyl chloride of 44 and then by palladium cyclization to construct both the xanthone and lactone moiety of 46. A Bringmann-type asymmetric cleavage using (S)-valinol (47) was then utilized to generate chiral biaryl xanthone 48. This compound was then further functionalized in nine steps to xanthene dialdehyde 49. The xanthone moiety revealed to be problematic in the key pinacol cyclization using SmI2 and was therefore removed prior to this key step. The pinacol cyclization occurred in good yield and trans/cis selectivity when pybox ligands such as (S,S)-iPr-pybox or (R,R)-iPr-pybox were utilized as additives with SmI2. The desired hexacyclic core (50) was obtained and then further transformed to FD-594 aglycone (51) in six steps.

Scheme 6.

Suzuki’s synthesis of FD-594 aglycon (51).

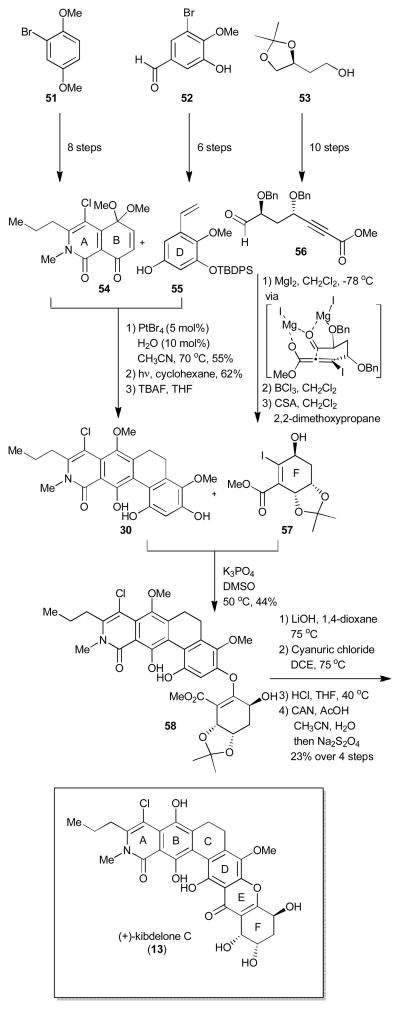

In 2011, both the Porco14 and Ready15 groups published their approaches to kibdelone C (13). These were the first examples of a total synthesis of a member of the polycyclic family which possess a non-aromatic xanthone ring system. For both groups, kibdelone C was approached in three fragments disconnecting at the C and E rings, nevertheless, the chemistry utilized to unite the hexacyclic core was drastically different (Scheme 7 and 8). The Porco group, first synthesized the AB (54) and D rings (55) independently from commercially available starting materials in eight and six steps respectively and then joined them one bond at a time to generate the ABCD (30) ring system of the natural product. The first bond between these two fragments was made using a novel Pt(IV)-catalyzed arylation between quinone monoketal 54 and hydroxystyrene 55. This was the first example of such a biaryl bond formation using sub-stoichiometric amounts of a metal.14b, 25 The C ring was then assembled using 6π-photochemical electrocyclization to yield 57 after cleavage of the silyl protecting group. The group then envisioned the use of an oxa-Michael/retro-Michael Friedel-Crafts annulation sequence to merge the ABCD (57) and F (58) rings into the desired hexacyclic ring-system. The chiral F ring (58) was access through the derivatization of commercially available chiral alcohol (53) in ten steps to ynoate 56 which was further cyclized using a highly diastereoselective intramolecular halo-Michael aldol (8:1) with MgI2 to obtain iodo-cyclohexene 58 once a two-step protecting group manipulation occurred. The protecting groups had to be changed from benzyls to an acetonide due to observed lack of reactivity of the allylic benzyl ether in oxa-Michael reactions. The ABCD ring was then merged to the F-ring using a site selective oxa-Michael reaction to yield vinylogus carbonate 59, a compound which was shown to be sensitive to both acid and heat. To close the tetrahydroxanthone ring, the authors overcame the lability of 59 by utilizing a 2 step mild cyanuric chloride cyclization. The acetonide was removed and the B ring was then oxidatively demethylated/reduced in situ using sodium dithionite to obtain (+)-kibdelone C (13). Such an oxidative/reductive procedure was necessary due to the observed and known nature of both kibdelone B and C to intrinsically interconvert (Scheme 2, Structure section).

Scheme 7.

Porco synthesis of (+)-kibdelone C.

Scheme 8.

Ready synthesis of (−)-kibdelone C.

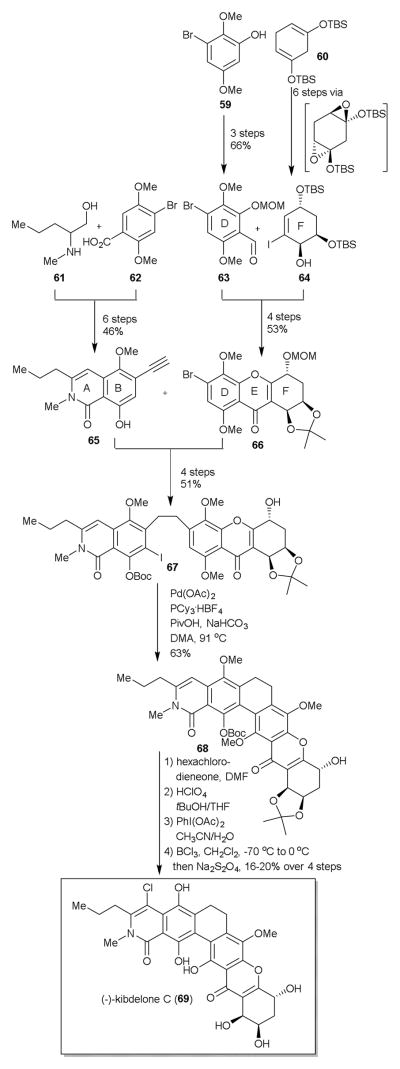

In contrast to the Porco group, the Ready group prepared the AB and DEF rings and then linked them together one bond at a time to form the C ring last (Scheme 8).

They envisioned for their synthetic approach that the final C-ring could be formed through a C-H arylation strategy, while for the F-ring they wanted to exploit the pseudo-C2 symmetry that related the two diols to one another. To establish the desired chirality of the cyclohexene F-ring (65), they utilized Myers methodology.26 The F-ring (65) was synthesized from commercially available bis(silylenol ether) 60 in 6 steps. Generation of the vinyl lithium species of 64 was followed by nucleophilic addition to aldehyde 63, previously synthesized in 3 steps from phenol 59. Dess-Martin oxidation of the derived alcohol followed by perchloric acid treatment in a tert-butanol/acetone mixture produced the acetonide-protected tetrahydroxanthone moiety which was further reprotected with a MOM group to yield 66 (53% yield, four steps). The obtained EFG ring system (66) was then coupled to the AB ring alkynyl system (65), prepared in six steps from amino alcohol 61 and carboxylic acid 62 using a Cu-free Sonogashira coupling. Next, hydrogenation of the newly formed pentacyclic core and Cu-mediated iodination yielded C-H arylation precursor 67. Extensive screening to find optimal conditions (67 to 68, Scheme 8) for the key C-H arylation was critical; ultimately Pd(OAc)2,PCy3.HBF4 with PivOH and NaHCO3 in DMA afforded 68 in 63%. The end-game to the Ready synthesis proved to be challenging with problems related to both installation of the chlorine onto the A ring, deprotection of the functional groups and obtaining the hydroquinone oxidation of the B ring. As was the case for the Porco group, stability issues between kibdelone B and kibdelone C were overcome by doing the final reduction in situ at the last step of the synthesis (see Structure section, Scheme 2). Although the unnatural (−)-enantiomer was prepared due to the initial chosen Shi reagent, one could utilize this approach to the natural enantiomer by using the antipodal Shi catalyst.

Although there has been great progress since 2009 towards the synthesis of the non-fully aromatic members of the polycyclic xanthone family (e.g. 5, 13), there have been no reports thus far towards members which possess both the challenging partially saturated polycyclic xanthones, such as tetrahydro-, and hexahydro-xanthone derivatives, and chirality on the polycyclic framework. This might be due to the lack of dependable methods for the construction of tetrahydro- and hexahydro-xanthone moieties which possess chirality on the ring system and the synthetic challenge of assembling such a massive hexacyclic ring system with also possess chirality on its polycyclic framework. For example, to functionalize the F-ring of kibdelone C it took 6 steps for the Ready group and 13 steps for the Porco group and in both cases the assembly for the core of the natural product came with unexpected problems and low yields.

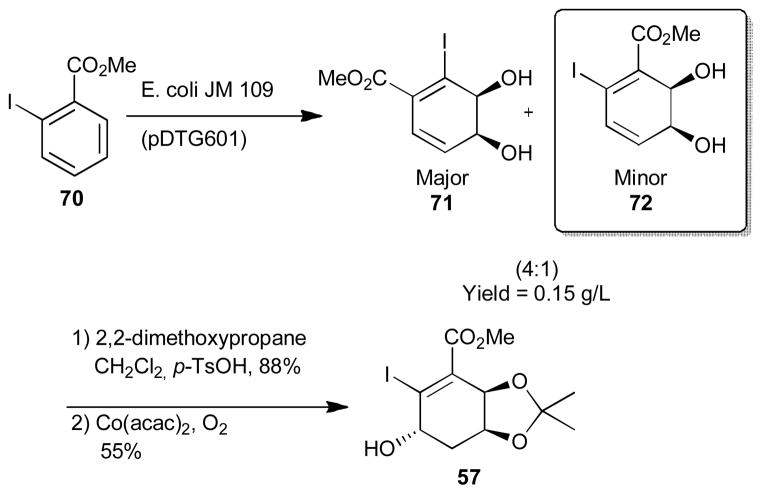

An alternative expeditious route to the F-ring of the kibdelones using microbial dihydroxylation (Scheme 9) was recently published by the Hudliky group.27 Dihydroxylation of methyl 2-iodobenzoate (70) using E.coli JM 109 (pDTG601) gave a mixture of diols 71 and 72 in a 4:1 mixture in a combined yield of 0.15g/L of fermentation broth. The desired minor diol (72) was then protected with an acetonide which was followed by Markonikov hydration using Co(acac)2 which afforded the desired F-ring synthon 57 in only 3 steps. An improved ratio for the enzymatic dihydroxylation using other halogens such as bromine (1:3.5) or fluorine (1:4) methyl benzoates is also possible and was recently reported by the Hudlicky group.28 Such short routes to polyhydroxylated cyclohexene ester fragments which circumvent the challenges of their construction will no doubt facilitate progress towards this family of natural products. However, the assembly of the tetrahydro-and hexahydro-xanthone substructures still remains quite challenging with very few reports on their synthesis.13d

Scheme 9.

Hudlicky’s microbial approach to the F-ring of the kibdelones.

Conclusions

The polycyclic xanthone family has intrigued both the biological and synthetic community for over forty years with their hexacyclic structure and multiple biological activities. In the last decade, increased reports of this novel class of molecules as potential antitumour agents has challenged the synthetic community to circumvent the innate challenges of the construction of this class of natural products and established viable synthetic routes for their synthesis in order to address the growing demand for novel chemotherapeutic agents. This article has showcased both the synthetic and pharmacological challenges and breakthrough for this family of natural products. Further progress towards the synthesis of members which possess both the challenging partially saturated polycyclic xanthones, such as tetrahydro-, and hexahydro-xanthone derivatives, and chirality on the polycyclic framework will no doubt be the subject of future efforts in this area. Future structure activity relationship studies on simplified fragments of the members of this natural product family are also necessary to ascertain both the key features related to activity and the mode of action of these natural products. Ultimately, development of novel methods for the construction of partially saturated xanthones and assembly of the derived hexacyclic structures will enable the synthetic community to access a variety of members of this novel family which will facilitate a greater understanding of this promising class of antitumour agents.

Contributor Information

David L. Sloman, Email: david_sloman@merck.com.

John A. Porco, Jr., Email: porco@bu.edu.

References

- 1.albufungin: Gurevich AI, Karapetyan MG, Kolosov MN, Oaelchenko K, Onoprienko V, Petrenko GI, Popravko SA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972;18:1751–1754.

- 2.simaomicin α: Lee TM, Carter GT, Borders DB. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1989;22:1771–1772.Carter GT, Goodman JJ, Torrey MJ, Borders DB, Gould SJ. J Org Chem. 1989;54:4321–4323.Koizumi Y, Tomoda H, Kumagai A, Zhou X-p, Koyota S, Sugiyama T. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:322–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01033.x.

- 3.actinoplanones: Kobayashi K, Nishin C, Ohya J, Sato S, Mikawa T, Shiobara Y, Kodama M. J Antibiot. 1988;4:741–750. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.741.Kobayashi K, Nishino C, Ohya J, Sato S, Mikawa T, Shiobara Y, Kodama M. J Antibiot. 1988;41:502–511. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.502.

- 4.lysolipins: Drautz H, Keller-Schierlein W, Zaehner H. Arch Microbiol. 1975;106:175–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00446521.Dobler M, Keller-Schierlein W. Helv Chim Acta. 1977;60:177–185. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19770600120.Duthaler RI, Mathies P, Heuberger WC, Scherrer V. Helv Chim Acta. 1984;67:1217–1221.Duthaler RO, Wegmann UH. Helv Chim Acta. 1984;67:1755–1766.Bockholt H, Udvarnoki G, Rohr J. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2064–2069.Lopez P, Hornung A, Welzel K, Unsin C, Wohlleben W, Weber T, Pelzer S. Gene. 2010;461:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.03.016.

- 5.cervinomycin A2: Omura S, Nakagawa A, Kushida K, Shimizu H, Lukacs G. J Antibiot. 1987;40:301–308. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.301.Mehta G, Venkateswarlu Y. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1988:1200–1202.Tanka H, Kawakita K, Suzuki H, Nakagawa PS, Omura SJ. J Antibiot. 1989;42:431–439. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.431.Kelly TR, Jagoe CT, Li Q. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:4522–4524.Mehta G, Shah SR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:5195–5198.Rao AV, Yadav JS, Reddy K, Upender V. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:5199–5202.Yadav JS. Pure Appl Chem. 1993;65:1349–1356.Mehta G, Shah SR, Venkateswarlu Y. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:11729–11742.

- 6.citreamycins: Carter GT, Nietsche JA, Williams DR, Borders DB. J Antibiot. 1990;43:504–512. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.43.504.Maiese WM, Lechevalier MP, Lechevalier HA, Korshalla J, Goodman J, Wildey MJ, Kuck N, Greenstein M. J Antibiot. 1989;42:846–851. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.846.Carter GT, Borders DB, Goodman JJ, Ashcroft J, Greenstein M, Maiese WM, Pearce CJ. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1991:2215–2219.

- 7.SCH 56036: Chu M, Truumees I, Mierzwa R, Terracciano J, Patel M, Das PR, Puar MS, Chan TM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7649–7652.Walker ER, Leung SY, Barrett AGM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:6537–6540.

- 8.kigamicin: Kunimoto S, Someno T, Yamazaki Y, Lu J, Esumi H. J Antibiot. 2003;56:1012–1017. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.1012.Someno T, Kunimoto S, Nakamura H, Naganawa H, Ikeda D. J Antibiot. 2005;58:56–60. doi: 10.1038/ja.2005.6.Masuda T, Ohba S, Kawada M, Osono M, Ikeda D, Esumi H, Kunimoto S. J Antibiot. 2006;59:209–214. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.29.

- 9.xantholipin: Terui Y, Yiwen C, Junying L, Ando T, Yamamoto H, Kawamura Y, Tomishima Y, Uchida S, Okazaki T, Munetomo E, Seki T, Yamamoto K, Murakami S, Kawashima A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:5427–5430.Zhang W, Wang L, Kong K, Wang T, Chu Y, Deng Z, You D. Chem Biol. 2012;19:422–432. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.016.

- 10.kibdelones: Ratnayake R, Lacey E, Tennant S, Gill JH, Capon R. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:1610–1619. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601236.

- 11.isokibdelones: Ratnayake R, Lacey E, Tennant S, Gill JH, Capon R. Org Lett. 2006;8:5267–5270. doi: 10.1021/ol062113e.

- 12.FD-594: Qiao Y, Okazaki T, Ando T, Mizoue K, Kondo K, Eguchi T, Kakinuma K. J Antibiot. 1998;51:282–287. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.282.Kondo K, Eguchi T, Kakinuma K, Mizoue K, Qiao Y. J Antibiot. 1998;51:288–295. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.288.Masuo R, Ohmori K, Hintermann L, Yoshida S, Suzuki K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3462–3465. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806338.

- 13.(a) Roberts JC. Chem Rev. 1961;61:591–605. [Google Scholar]; (b) Peres V, Nagem TJ, de Oliviera FF. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:683–710. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pinto M, Sousa E, Nascimento M. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2517–2538. doi: 10.2174/092986705774370691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Masters KS, Bräse S. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3717–3776. doi: 10.1021/cr100446h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Sloman DL, Mitasev B, Scully SS, Beutler JA, Porco JA., Jr Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2511–2515. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sloman DL, Bacon JW, Porco JA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9952–9955. doi: 10.1021/ja203642n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler JR, Wang C, Bian J, Ready JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9956–9959. doi: 10.1021/ja204040k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo F, Yonezawa T, Komatsubar A, Mizoue K, Eguchi T. J Antibiot. 2011;64:123–132. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eguchi T, Kondo K, Kakinuma K, Uekusa H, Ohashi Y, Mizoue K, Qiao YF. J Org Chem. 1999;64:5371–5376. doi: 10.1021/jo982182+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peoples AJ, Zhang Q, Millet WP, Rothfeder MT, Pescatore BC, Madden AA, Ling LL, Moore CM. J Antibiot. 2008;61:457–463. doi: 10.1038/ja.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu M, Truumees I, Mierzwa R, Terracciano J, Patel M, Leonberg D, Kaminski JJ, Das P, Puar MS. J Nat Prod. 1997;60:525–528. doi: 10.1021/np960737v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner PA, Griffin EM, Whatmore JL, Shipman M. Org Lett. 2011;13:1056–1059. doi: 10.1021/ol103103n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du XG, Wang W, Zhang SP, Pu XP, Zhang QY, Ye M, Zhao YY, Wang BR, Khan JA, Guo DA. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:1422–1426. doi: 10.1021/np100008r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Katayama S, Nakashita Y, Yamauchi M. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans I. 1978:726–729. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu J, Kunimoto S, Yamazaki Y, Kaminishi M, Esumi H. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Boyd MR, Paull KD. Drug Dev Res. 1995;34:91–109. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shoemaker RH. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.a) Sartori G, Maggi R, Bigi F, Grandi M. J Org Chem. 1993;58:7271–7273. [Google Scholar]; b) Sartori G, Maggi R, Bigi G, Giacomelli S, Porta C, Arienti A, Bocelli G. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1995:2177–2181. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim SM, Hill N, Myers AG. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5763–5765. doi: 10.1021/ja901283q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Endoma-Arias MAA, Hudlicky T. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:6632–6634. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semak V, Metcalf TA, Endoma-Arias MAA, Mach P, Hudlicky T. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:4407–4416. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25202c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]