Abstract

A major goal of biomedical research has been the identification of molecular mechanisms that can enhance memory. Here we report a novel signaling pathway that regulates the conversion from short- to long-term memory. The mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), which contains the key regulatory protein Rictor (Rapamycin-Insensitive Companion of mTOR), was discovered only recently, and little is known about its physiological role. We show that conditional deletion of rictor in the postnatal murine forebrain greatly reduces mTORC2 activity and selectively impairs both long-term memory (LTM) and the late (but not the early) phase of hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP). Actin polymerization is reduced in the hippocampus of mTORC2-deficient mice and its restoration rescues both L-LTP and LTM. More importantly, a compound that selectively promotes mTORC2 activity converts early-LTP into late-LTP and enhances LTM. These findings indicate that mTORC2 could be a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of cognitive dysfunction.

Keywords: mTOR complexes, actin assembly, spatial memory, fear memory, cognitive enhancer

Introduction

How memories are stored in the brain is a question that has intrigued mankind over many generations. While neuroscientists have already made great strides indentifying key brain regions and relevant neuronal circuits, many questions regarding the specialized molecular and neuronal mechanisms underlying memory formation remain unanswered. Post-translational modifications of synaptic proteins can explain transient changes in synaptic efficacy, such as short-term memory (STM) and the early phase of LTP (E-LTP, lasting 1-3 hours); but new protein synthesis is required for long-lasting ones, such as LTM and the late phase of LTP (L-LTP, lasting several hours)1-7. Changes in actin dynamics that mediate structural changes at synapses are also necessary for L-LTP and for LTM storage8-10. However, relatively little is known about the molecular mechanisms that underlie these processes.

The evolutionarily conserved mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) forms two complexes11-13. The first, mTORC1, consist of mTOR, Raptor and mLST8 (GβL), is sensitive to rapamycin, and is thought to regulate mRNA translation3. Although significant progress has been made in the identification of the mTORC1 pathway and understanding its function in cells and in vivo, much less is known about the second complex, mTORC2. mTORC2 is largely insensitive to rapamycin and contains the core components mTOR, mSIN1, mLST8 and Rictor (Rapamycin-Insensitive Companion of mTOR). Rictor is a defining component of mTORC2 and its interaction with mSIN1 appears to be required for mTORC2 stability and function14. Rictor is associated to membranes and is thought to regulate the actin cytoskeleton, but the precise molecular mechanism behind this effect remains unclear11,12,16. In addition, while little is known about mTORC2’s up-stream regulation, we are beginning to understand its downstream regulation and effectors: mTORC2 phosphorylates AGC kinases at conserved motifs, including Akt at the hydrophobic motif (HM) site (Ser-473), the best characterized read out of mTORC2 activity11,12.

The key component of mTORC2, Rictor, is important for embryonic development as mice lacking rictor die in early embryogenesis15,16. Rictor is highly expressed in the brain, notably in neurons16, and it seems to play a crucial role in various aspects of brain development and function. For example, genetic deletion of rictor in developing neurons disrupts normal brain development, resulting in smaller brains and neurons, as well as increased levels of monoamine transmitters and manifestations of cerebral malfunction suggestive of schizophrenia and anxiety-like behaviors17,18.

Given that i) actin polymerization is critically required for memory consolidation8-10, ii) mTORC2 appears to regulate the actin cytoskeleton11,12,19, and iii) mTORC2’s activity is altered in conditions associated with memory loss, such as aging and several cognitive disorders, including Huntington’s disease, Parkinsonism, Alzheimer-type dementia and Autism Spectrum Disorders20-25, we decided to investigate its potential role in memory formation, specifically in sustained changes in synaptic efficacy (LTP) in hippocampal slices, and in behavioral tests of memory. Our results show that through regulation of actin polymerization, mTORC2 is an essential component of memory consolidation. Briefly, we report here a selective impairment in L-LTP and LTM in mice and flies deficient in TORC2 signaling. Moreover, we have identified the up-stream synaptic events which activate mTORC2 in the brain and unraveled the detail downstream molecular mechanism by which mTORC2 regulates L-LTP and LTM, namely regulation of actin polymerization. Finally, a small molecule activator of mTORC2 and actin polymerization facilitates both L-LTP and LTM, further demonstrating that mTORC2 is a new type of molecular switch that controls the consolidation of a short-term memory process into a long-term one.

Results

Characterization of rictor forebrain-specific knockout (rictor fb-KO) mice

Pharmacological inhibitors of mTORC2 are not available, and mice lacking rictor in the developing brain show abnormal brain development. To circumvent this problem, we conditionally deleted rictor in the postnatal forebrain by crossing “floxed” rictor mice16 with the α subunit of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (αCaMKII)-Cre mice26, generating rictor forebrain-specific knockout mice (rictor fb-KO mice; see Methods and Supplementary Fig. 10). Because the αCaMKII promoter is inactive before birth27, this manipulation diminishes possible developmental defects caused by the loss of rictor.

Rictor fb-KO mice are viable and develop normally. They show neither gross brain abnormalities nor changes in the expression of several synaptic markers (Supplementary Fig. 1). mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 (an established readout of mTORC2 activity11,12) was greatly reduced in CA1 and amygdala (Fig. 1a-b), but was normal in the midbrain (Fig. 1c) of rictor fb-KO mice. By contrast, in mTORC2-deficient mice, mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of S6K1 at Thr389 (a well-established readout of mTORC1 activity28) remained unchanged in CA1, amygdala or midbrain (Fig. 1a-c). Thus, conditional deletion of rictor selectively reduces mTORC2 activity in forebrain neurons.

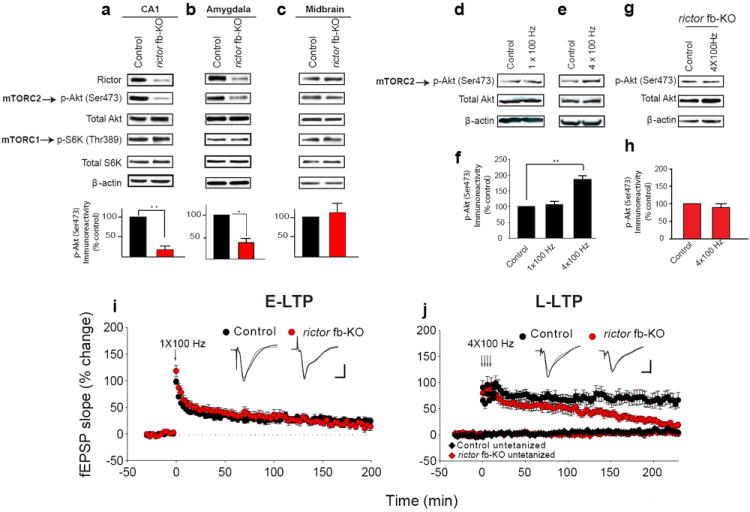

Fig. 1. L-LTP, but not E-LTP, is impaired in mTORC2-deficient slices.

a-c) Western blots show selective decrease in Rictor and mTORC2 activity (p-Akt Ser473) in CA1 (a) and amygdala (b) but not in midbrain (c) of rictor fb-KO mice. Below: normalized data (a; n=4 per group, t=9.794, **p<0.01; b; n=5 per group, t=2.976, *p < 0.05, c; n=4 per group, t=0.470, p=0.663). d-e) In CA1 extracts from control mice 30 min post-stimulation mTORC2 activity was consistently increased with four tetanic trains, but not a single train. Hippocampal slices were stimulated at 0.033 Hz (control), tetanized by one train (100 Hz for 1 s; d), or four such trains at 5 min intervals (e). f) Normalized mTORC2 activity (n=5 per group, 1 X 100 Hz: t=0.31, p=0.23; 4 X 100 Hz: t=6.01, **p<0.01). g) In CA1 from rictor fb-KO mice repeated trains failed to increase mTORC2 activity 30 min after stimulation. h) Normalized data (n=5 per group, U=5.00, p=0.151). i) Similar E-LTP was elicited in control (n=9) and rictor fb-KO slices (n=8) (LTP at 30 min: 41 ± 5.6% for controls and 44 ± 5.7% for rictor fb-KO, F(1, 14)=0.130, p=0.724; LTP at 180 min: 23.7 ± 5.3% for controls and 24.7 ± 8.5% for rictor fb-KO, F(1, 15)=0.011, p=0.917). j) L-LTP elicited by four trains in rictor fb-KO slices (n=11) was impaired vs. control slices (n=14; LTP was similar at 30 min, control 72 ± 11.3% and rictor fb-KO 67 ± 13.2%, F(1, 23)=0.811, p=0.368; but at 220 min L-LTP was only 21 ± 10.8% for rictor fb-KO slices vs. 70 ± 14.8% for controls; F(1, 23)=23.4, p<0.01). Superimposed single traces were recorded before and 180 min after tetani (i) or before and 220 min after tetani (j). Calibration: 5 ms, 2 mV.

Deficient mTORC2 activity prevents L-LTP but not E-LTP in rictor fb-KO mice

To investigate the role of mTORC2 in synaptic function, we first showed that mTORC2 is activated in CA1 by either glutamate [via NMDA receptor (NMDAR)] or neurotrophins (Supplementary Fig. 2). Next, to determine whether short-term or long-term changes in synaptic potency alter mTORC2 activity, we compared the effects of one train of tetanic stimulation (100 Hz for 1s), which usually induces only short-lasting E-LTP, with that of four such trains (which typically induce a long-lasting L-LTP)1. Only an L-LTP-inducing stimulation consistently activated mTORC2 in CA1 neurons of control (Fig. 1d-f) but not rictor fb-KO mice (Fig. 1g-h). Hence, mTORC2 is engaged selectively in long-lasting synaptic changes in synaptic strength.

We then examined whether mTORC2 deficiency affects either E-LTP or L-LTP. Whereas a single train of tetanic stimulation generated a similar E-LTP in slices from rictor fb-KO and control littermates (Fig. 1i), four trains elicited a normal L-LTP in control littermates slices, but not in rictor fb-KO slices (Fig. 1j). Several tests showed that the impaired L-LTP in mTORC2-deficient slices cannot be attributed to defective basal synaptic transmission (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, reducing mTORC2 activity prevents the conversion of E-LTP into L-LTP.

Deficient TORC2 activity selectively impairs long-term memory both in mice and flies

Since L-LTP-inducing stimulation increases mTORC2 activity, we then investigated whether mTORC2 is activated as a result of behavioral learning. Contextual fear conditioning, induced by pairing a context (conditioned stimulus; CS) with a foot shock (unconditioned stimulus; US), resulted in sharp temporarily increase in mTORC2 activity and phosphorylation of the p21-activated kinase PAK (a key regulator of actin cytoskeleton dynamics29,30) 15 min after training (Fig. 2a-b). In contrast, the shock-alone (US) and the context-alone (CS) failed to increase mTORC2 activity (Fig. 2c). Thus, hippocampal mTORC2 is selectively activated by behavioral learning (CS+US).

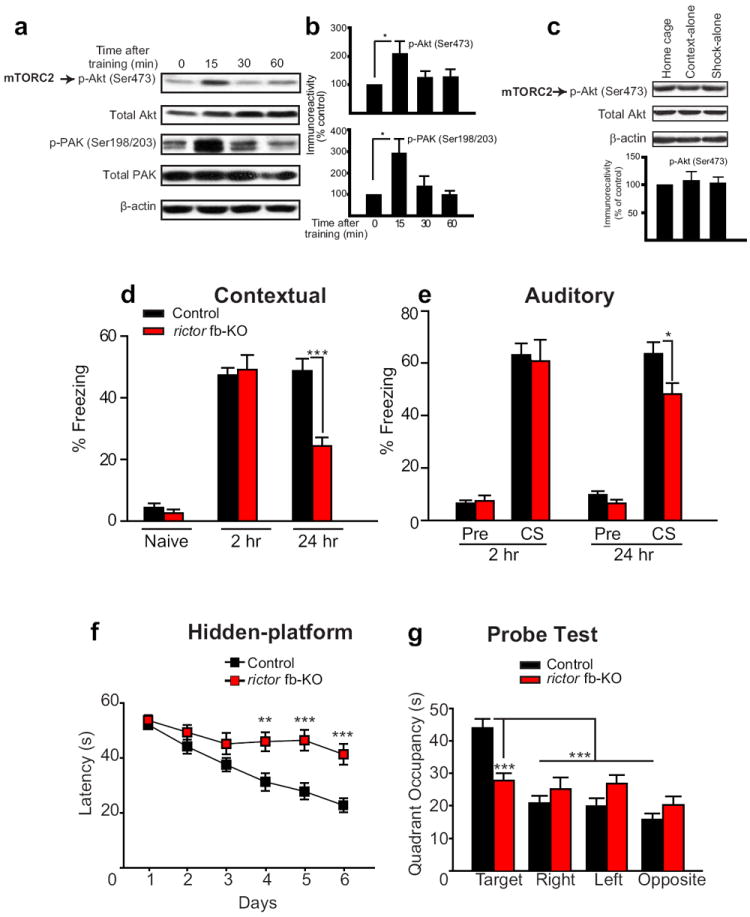

Fig. 2. Long-term, but not short-term, fear memory is impaired in mTORC2-deficient mice.

a) In Western blots of control dorsal hippocampus, phosphorylation of both Akt at Ser473 and PAK is transiently enhanced 15 min after fear conditioning. b) Normalized data (top, n=6 per condition, t=2.599, *p<0.05; bottom, n=5 per condition, t=2.930, *p<0.05). c) Compared to home-cage mice, either context-alone (CS) or shock-alone (US) failed to increase mTORC2 activity (n=4 per group, F(2,9)=0.127, p=0.882). In the context-alone group (CS) mice were treated identically but were not given foot shocks whereas in the shock alone group (US) mice were given two foot-shocks and were immediately removed from the chamber. d) For contextual fear conditioning, freezing was assessed in control (n=22) and rictor fb-KO mice (n=14) during a 2 min period before conditioning (naïve) and then during a 5 min period at 2hr (STM) and 24 hr (LTM) after a strong training protocol (two pairings of a tone with a 0.7 mA foot-shock, 2s). e) For auditory fear conditioning, freezing was assessed 2 hr and 24 hr after training, for 2 min before the tone presentation (pre-CS) and then during a 3 min period while the tone sounded (CS). Decreased freezing at 24 hr after training indicates deficient fear LTM in rictor fb-KO mice (d, F(1, 34) =20.253, ***p<0.001; e, F(1,34) =4.704, *p<0.05). f-g) Spatial LTM is impaired in rictor fb-KO mice. f) In the hidden-platform version of the Morris water maze, on days 4, 5 and 6 escape latencies were significantly longer for rictor fb-KO mice (F(1,37)=8.585; **p<0.01; F(1,37)=14.651; ***p<0.001, F(1,37)=18.101, ***p<0.001). g) In the probe test on day 7, only control mice showed preference for the target quadrant (control vs. rictor fb-KO mice; F(1,37)=15.554, ***p<0.001; within control group F(3, 96)=28.840, ***p<0.001).

We next studied memory storage in two forms of Pavlovian conditioning, contextual and auditory fear conditioning. Contextual fear conditioning involves both the hippocampus and amygdala whereas auditory fear conditioning, in which the foot shock (US) is paired with a tone (CS), requires only the amygdala31. When mice were subsequently exposed to the same CS, fear responses (“freezing”) were taken as an index of the strength of the CS-US association. Rictor fb-KO mice and control littermates showed similar “freezing” behavior before training (naïve) and 2 hr after training, when their STM was measured (Fig. 2d-e). However, when examined 24 hr after training, both contextual and auditory LTM were significantly impaired in mTORC2-deficient mice (Fig. 2d-e). The less pronounced change in auditory fear LTM vs. contextual fear LTM in rictor fb-KO mice may be explained by the smaller reduction in mTORC2 activity in the amygdala (compare Fig. 1a vs. Fig. 1b). Spatial LTM was also deficient in rictor fb-KO mice when tested in the Morris water maze, where animals use visual cues to find a hidden platform in a circular pool32. Compared to controls, rictor fb-KO mice took significantly longer to find the hidden platform (Fig. 2f), and in the probe test, performed on day 7 in the absence of the platform, they failed to remember the platform location (target quadrant; Fig. 2g). The impaired spatial LTM was probably not caused by deficient visual or motor function since control and rictor fb-KO mice performed similarly when the platform was visible (Supplementary Fig. 4) and showed no significant difference in swimming speed (19.8 ± 0.6 vs. 19.6 ± 0.5 cm/s for control and rictor fb-KO mice). Hence, mTORC2 selectively fosters long-term memory processes.

Because TORC2 is evolutionarily conserved11,12, we also wondered whether its function in memory formation is maintained across the animal phyla. To this end, we studied olfactory memory in wild-type controls (Canton-S) and Drosophila TORC2 (dTORC2)-deficient fruit flies. As expected, in the brain of rictor mutant flies (rictorΔ1)33 dTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif of Drosophila Akt (dAkt) at Ser505 (an established readout of dTORC2 activity34) was greatly reduced (Fig. 3a). As in mammals, LTM in Drosophila is protein-synthesis dependent35 and it is generated after “spaced” training (5 training sessions with a 15-min rest interval between each; Fig. 3b). By contrast, “massed training” (5 training sessions with no rest intervals) fails to elicit LTM but rather induces the anesthesia-resistant, protein-synthesis independent memory (ARM; Fig. 3b)35. Although responses to olfactory stimuli or electric shocks did not differ significantly between rictorΔ1 and control flies (Fig. 3c-e), in rictorΔ1 flies LTM was blocked, whereas the short-lasting ARM was unaffected (Fig. 3f). Thus, both in fruit flies and mice TORC2 promotes LTM storage.

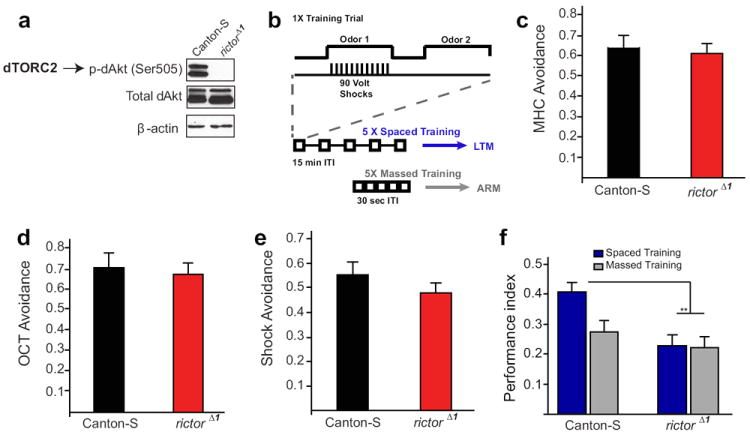

Fig. 3. In TOR2-deficient Drosophila, long-term spaced memory (but not massed) is impaired.

a) Western blotting for p-dAkt (Ser505), total dAkt and β-actin in the brain of control Canton-S and rictorΔ1 mutant flies. b) In olfactory conditioning, a single training trial consists of 12 electric shocks delivered during the presentation of an odor, while a second odor is explicitly unpaired with the shocks. LTM of the conditioned odor is generated when flies are given five such training trials at 15 min intervals (“spaced training”). However, if the five training trials are given with at much shorter (30 sec) intervals (“massed training”) only a shorter-lasting Anesthesia Resistant Memory (ARM) is formed, but not LTM. c-d) WT Canton-S and rictorΔ1 flies did not significantly differ in the avoidance of 0.12% methylcyclohexanol (MCH; c; t=0.47, p=0.647) and 0.2% octanol (OCT; d; t=1.86. p=0.99). e) Both Canton-S and rictorΔ1 flies similarly avoided the T-maze arm with 90V electric shocks (t=1.86, p=0.17). For each sensory control experiment, an “n” was at least 9 for either genotype. Performance index was calculated as described61. f) In Drosophila olfactory memory tests, spaced training-induced LTM was selectively impaired in rictorΔ1 flies (t=4.37, **p<0.01). In contrast, massed training elicited a similar performance in of both Canton-S (controls) and rictorΔ1 flies (t=1.10, p=0.3). Spaced training did not significantly improve the performance of rictorΔ1 mutants over that achieved through massed training protocols (t=019, p=0.85). n=6 for each group.

Deficient actin dynamics and Rac1-GTPase-mediated signaling in CA1 neurons of rictor fb-KO mice

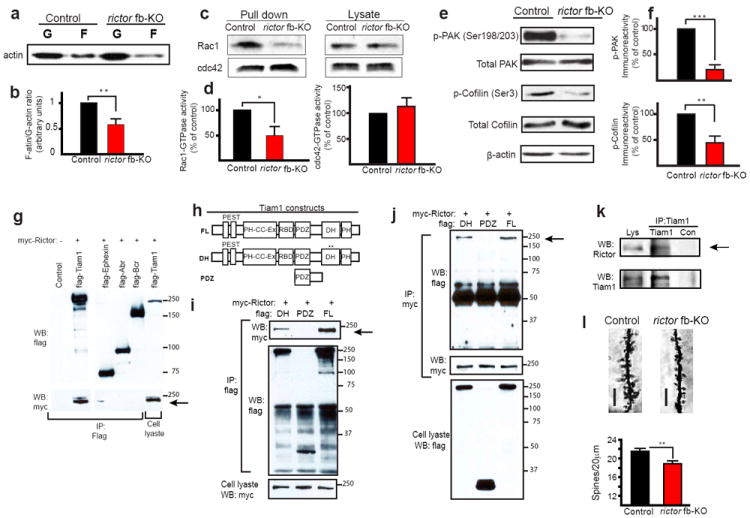

We also probed the molecular mechanism by which mTORC2 regulates L-LTP and LTM by first testing whether mTORC2 deficiency impairs actin dynamics in CA1 neurons in vivo. Actin exists in two forms: monomeric globular actin (G-actin) and polymerized filamentous actin (F-actin) composed of aggregated G-actin. The transition between these two forms is controlled by synaptic activity8,9. The ratio of F-actin to G-actin, which reflects the balance between actin polymerization and depolymerization, was significantly reduced in CA1 of rictor fb-KO mice (Fig. 4a-b). Since Rho-GTPases have been identified as key intracellular signaling molecules that regulate actin dynamics at synapses36, we measured the activity of Rho-GTPases in CA1 of mTORC2-deficient mice. Rac1 (Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1) and Cdc42 (cell division cycle 42), two major Rho GTPases, induce actin polymerization by promoting PAK and Cofilin phosphorylation8. Rac1-GTPase activity (but not Cdc42 activity) and the phosphorylation of PAK and Cofilin were greatly diminished in CA1 neurons of rictor fb-KO mice (Fig. 4c-f). Moreover, we found that the Rac1-specific guanine nucleotide-exchange factor (GEF) Tiam1 links Rictor (mTORC2) to Rac1 signaling (Fig. 4g-k). Finally, dendritic spine density in CA1 pyramidal neurons was significantly reduced in rictor fb-KO mice (Fig. 4l). Thus, in the adult hippocampus, mTORC2 regulates actin dynamics-mediated changes in synaptic potency and architecture.

Fig. 4. Actin dynamics, Rac1-GTPase activity and signaling are impaired in CA1 of rictor fb-KO mice.

a-f) Western blotting shows that the ratio of F-actin/G-actin (a), Rac1-GTPase activities (c), p-PAK and p-Cofilin (e) are much reduced in CA1 of rictor fb-KO mice. Normalized data (b; n=4 per group, t=4.042, **p<0.01; d left; n=4 per group, t=2.762, *p<0.05; d right; n=4 per group, t=0.519, p=0.623; f; p-PAK n=4 per group, t=9.054, ***p<0.001; p-Cofilin n=4 per group, t=4.486, **p<0.01). g) We hypothesized that mTORC2 regulates Rac1-GTPase activity (and signaling) through the recruitment of a specific Rac1-GTPase GEF. To test this hypothesis, we co-transfected HEK293T cells with myc-tagged Rictor and flag-tagged GEFs or GAPs, and then performed co-immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments. myc-Rictor selectively pulled-down flag-Tiam1 (T-cell-lymphoma invasion and metastatis-1), a specific Rac1-GEF that is highly enriched in neurons62. Flag-tagged -Tiam1, -ephexin, -Abr and –Bcr were coexpressed in HEK293T cells with myc-Rictor and anti-flag immunoprecipitates were analyzed by anti-flag (top) and anti-myc (middle) immunoblotting. h) Diagram of the Tiam1 constructs (FL=full length, DH=point mutations in the DH domain; PDZ=deletion mutant encoding only the PDZ domain). Flag-tagged FL, DH or PDZ were co-expressed with myc-tagged Rictor in HEK293T cells. i) Anti-flag immunoprecipitates were analyzed by anti-myc (top) and anti-flag (middle) immunoblots whereas anti-myc immunoprecipitates (j) were analyzed by anti-flag (top) and anti-myc immunoblots (middle). k) Endogenous Tiam1 interacts with endogenous Rictor. Immunoprecipitates of anti-Tiam1 or anti-IgG (control) were prepared from adult hippocampal extracts and analyzed by Rictor (top) and Tiam1 (bottom) immunoblots. Arrows point to the interaction between Tiam1 and Rictor. l) Golgi-impregnation shows that spine density of apical CA1 pyramidal neurons is reduced in rictor fb-KO mice [scale bar 5 μm; n=70 (20-25 neurons/mouse; 3 mice per group), t=2.791, **p<0.01].

Restoring actin polymerization rescues the impaired L-LTP and LTM caused by mTORC2 deficiency

If L-LTP is impaired in mTORC2-deficient slices because actin polymerization is abnormally low, increasing the F-actin/G-actin ratio should convert the impaired, short-lasting LTP elicited by four tetanic trains into a normal L-LTP. We therefore predicted that jasplakinolide (JPK), a compound which directly promotes actin polymerization37, should restore the normal function. Indeed, a low concentration of JPK (50 nM), raised the low F-actin/G-actin ratio and restored L-LTP in rictor fb-KO slices (Fig. 5a-b), but had no effect on wild-type (WT) slices (Fig. 5a, c) or on baseline synaptic transmission in rictor fb-KO slices (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In addition, cytochalasin D, an inhibitor of actin polymerization, blocked L-LTP in WT slices (Fig. 5c), but had no effect on the short-lasting LTP evoked either by a single tetanic train in control slices (Supplementary Fig. 5b) or by repeated tetanic stimulation in mTORC2-deficient slices (Fig. 5b). The deficient L-LTP in mTORC2-deficient slices is therefore primarily caused by impaired actin polymerization.

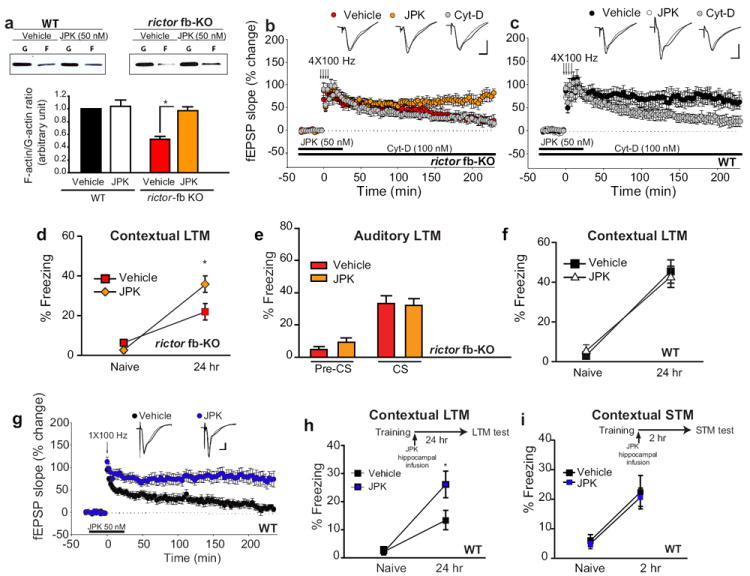

Fig. 5. Restoring actin polymerization rescues the impaired L-LTP and contextual LTM caused by mTORC2 deficiency.

a) Western blots show that jasplakinolide (JPK; 50 nM) increased the low F-actin/G-actin ratio in CA1 slices from rictor fb-KO mice (n=4 per group, t=3.821, *p<0.05) but not in control slices (n=4 per group, t=0.253, p=0.157). b) The same concentration of JPK restored L-LTP in rictor fb-KO slices (n=7 per group, LTP at 30 min, vehicle 67 ± 7.7%, JPK 73 ± 11.3%, H=0.0667, ANOVA on Ranks, p=0.852; LTP at 220 min, vehicle 23 ± 4.9%, JPK 73 ± 12.5%, F(1, 12)=9.81, p<0.01) but had no effect on L-LTP in WT slices (c; n=7 per group, LTP at 30 min: vehicle 74 ± 9.4%, JPK 72 ± 11.4%, F(1, 12)=0.989, p=0.784; LTP at 220 min: vehicle 64 ± 8.7%, JPK 68 ± 14.2%; F(1, 12)=0.010, p=0.921). The actin polymerization inhibitor Cytochalasin-D (Cyt-D; 100 nM) blocked L-LTP in WT slices (c; at 220 min 26 ± 7.8%, F(1,12)=9.215, p<0.01) but had no effect in rictor fb-KO slices (b, at 220 min 21 ± 7.9%, F(1, 13)=0.163, p=0.694). Insets in b and c are superimposed traces recorded before and 220 min after tetani. Calibration: 5 ms, 2 mV. d-e) Bilateral infusion of JPK (50 ng) into the dorsal hippocampus of rictor fb-KO mice (n=8 per group), immediately after a strong training protocol (two pairings of a tone with a 0.7 mA foot-shock, 2s), boosted contextual LTM (d; F(1, 14)=4.827, *p<0.05) but not auditory LTM (e; F(1, 14)=0.0407, p=0.843). Freezing was assessed 24 hr after training, as described in Fig. 2. f) In WT mice (n=8 per group) JPK bilateral infusion (50 ng) had no effect on contextual LTM (F(1, 14)=0.129, p=0.726). g) A single tetanic train elicits only E-LTP in vehicle-treated slices but a sustained L-LTP in JPK-treated slices (n=7 for vehicle, n=8 for JPK; LTP at 180 min: vehicle 19 ± 5.2%, JPK 81 ± 14.5%, ANOVA on Ranks H=10.59; p<0.001). Inset in g are superimposed single traces recorded before and 180 min after tetani. Calibration: 5 ms, 2 mV. h) Intra-hippocampal infusion of JPK immediately after a weak training (a single pairing of a tone with a 1s, 0.7 mA foot-shock) enhanced contextual fear LTM (n=15 for vehicle and n=16 for JPK; F(1, 29)=4.320, *p<0.05) but not contextual fear STM (i, n=9 for vehicle and n=10 for JPK, H=0.00167, ANOVA on Ranks, p=0.967).

To determine whether deficient actin dynamics underlie the impaired LTM in rictor fb-KO mice, we bilaterally infused JPK into the CA1 region (Supplementary Fig. 6), at a low dose (50 ng) that promoted F-actin polymerization only in rictor fb-KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 7a). JPK infused immediately after training boosted contextual LTM (Fig. 5d), but had no comparable effect on hippocampus-independent auditory LTM (Fig. 5e) in rictor fb-KO mice or on contextual LTM in WT mice (Fig. 5f). These pharmacogenetic rescue experiments provide strong evidence that deficient actin dynamics account, at least in part, for the impaired LTM in rictor fb-KO mice.

Direct stimulation of actin polymerization promotes L-LTP and enhances LTM

Given that i) a short-lasting LTP is evoked by either repeated tetanic stimulation in mTORC2-deficient slices (Fig. 1i) or by a single tetanic train in control slices (Fig. 1h) and ii) JPK restored the deficient L-LTP in mTORC2-deficient slices (Fig. 5b), we predicted that JPK would facilitate the induction of L-LTP in control slices. Combining JPK with a weak stimulation, that normally elicits only a short-lasting E-LTP, we found that indeed JPK lowers the threshold for the induction of L-LTP in WT slices (Fig. 5g).

Having shown that boosting actin polymerization converts short-lasting LTP into long-lasting LTP, we next wondered whether this JPK-facilitated L-LTP depended on new protein synthesis. We found that the sustained LTP induced by a single train at 100 Hz in combination with JPK was blocked by the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Furthermore, JPK could not rescue the impaired L-LTP induced by four trains at 100 Hz in the presence of anisomycin (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These data indicate that the actin cytoskeleton-mediated facilitation of L-LTP depends on protein synthesis.

We then bilaterally-infused JPK or vehicle into CA1 of WT mice immediately after a weak Pavlovian fear conditioning training (a single pairing of a tone with a 1s, 0.7 mA foot-shock). This protocol generated only a relatively weak memory in vehicle-infused mice, as measured 24 hr after training (Fig. 5h). In contrast, in JPK-infused mice the same protocol induced a greatly enhanced contextual fear LTM (Fig. 5h). As expected, JPK had no effect on contextual fear STM (Fig. 5i) or hippocampus-independent auditory fear LTM (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Because JPK acts directly on actin itself by increasing its polymerization37, our data support the idea that actin polymerization is an essential mechanism for the consolidation of L-LTP and LTM.

Selective activation of mTORC2 by A-443654 facilitates L-LTP and enhances LTM

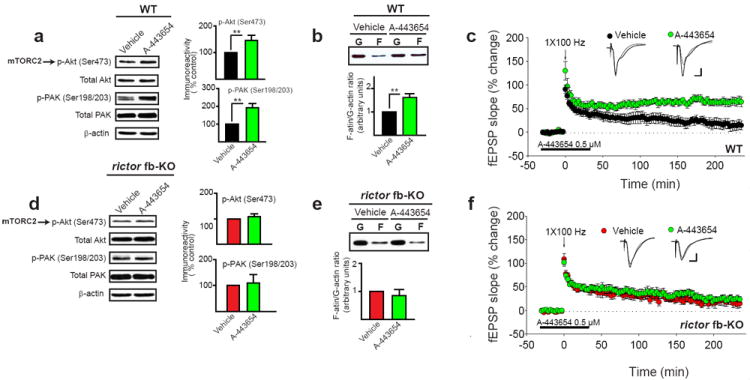

We then reasoned that direct activation of mTORC2 signaling should convert short- to long-lasting memory processes (for both LTP and LTM). To test this hypothesis, we employed a small molecule (A-443654), which increases mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 (independently of mTORC138). We found that A-443654 promoted mTORC2 activity, PAK phosphorylation, as well as actin polymerization in WT slices (Fig. 6a-b), but not in mTORC2-deficient slices (Fig. 6d-e). More importantly, A-443654 converted a short-lasting E-LTP into a sustained L-LTP in WT slices (Fig. 6c), but it failed to do so in rictor fb-KO slices (Fig. 6f). Thus, the facilitated L-LTP induced by combining A-443654 and a single high frequency train is mediated by mTORC2.

Fig. 6. A-443654 promotes mTORC2 activity, actin polymerization and facilitates L-LTP in WT mice but not in mTORC2-deficient mice.

a-b) Treating WT hippocampal slices for 30 min with A-443654 (0.5 μM) increased the activity of both mTORC2 and PAK (a; n=5, U=0.00, **p<0.01; n=4, U=0.00, **p<0.01), as well as the F-actin/G-actin ratio (b; n=5, t=3.995, **p<0.01). c) A-443654 (0.5 μM) converted E-LTP elicited by single tetanic train into a sustained L-LTP in WT slices (n=6 for vehicle, n=8 for A-443654; LTP at 180 min: vehicle 17 ± 10.6%, A-443654 69 ± 7.1%, F(1, 12)=17.870, p<0.001). d-e) A-443654 (0.5 μM) had no effect on mTORC2 and PAK activities (d; n=4, t=0830, p=0.438; n=4; t=0.290, p=0.777) or on actin polymerization in rictor fb-KO slices (e; n=3, t=0.680, p=0.534). f) A-443654 failed to induce L-LTP in rictor fb-KO slices (n=6 for vehicle, n=7 for A-443654; LTP at 180 min: vehicle 24 ± 8.2%, A-443654 28 ± 6.2%, F(1, 11)=2.25, p=0.167). Insets in c and f are superimposed traces recorded before and 180 min after tetani. Calibration: 5 ms, 2 mV.

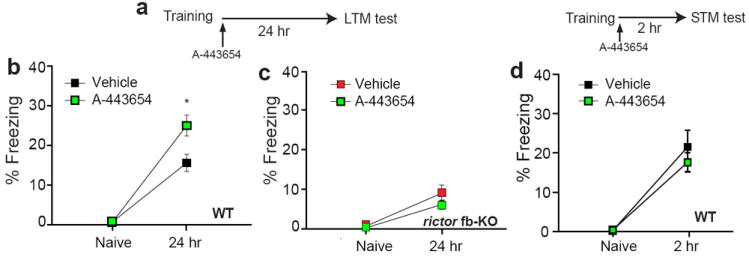

If mTORC2 is involved in learning and memory, acute activation of mTORC2 should also promote LTM. Indeed, in WT mice, an intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection of A-443654 increased the activity of both mTORC2 and PAK in the hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 9). In addition, when WT mice were i.p-injected with either vehicle or A-443654 immediately after a weak Pavlovian fear conditioning training (a single pairing of a tone with a 1s, 0.7 mA foot-shock; Fig. 7a), we found that 24 hr later the A-443654-injected mice froze nearly twice as often as vehicle-injected controls, indicating that their contextual LTM was enhanced (Fig. 7b). By contrast, A-443654 failed to enhance contextual LTM in mTORC2-deficient mice (Fig. 7c), confirming the selectivity of A-443654. The facts that A-443654 was injected post-training and that contextual STM is not altered by A-443654 (Fig. 7d) argue against non-specific responses to fear. Taken together these pharmacogenetic data provide compelling evidence that A-443654’s enhancing effect on synaptic plasticity and behavioral learning is crucially dependent on mTORC2.

Fig. 7. A-443654 selectively enhances LTM in WT mice but not in mTORC2-deficient mice.

a) Diagram of the experimental protocol. b) A single A-443654-injection (2.5 mg/kg i.p.) immediately after a weak training (a single pairing of a tone with a 1s, 0.7 mA foot-shock) enhanced contextual fear LTM in WT mice (n=18 per group; F(1, 34)=6.007, *p<0.05) but not in rictor fb-KO mice (c, n=10 per group; F(1, 18)=1.648, p=0.22). d) Similar freezing at 2 hr reflects normal contextual fear STM in vehicle-injected and A-443654-injected WT mice (n=9 for vehicle and n=10 for A-443654; F(1, 17)=0.6, p=0.449). Freezing was assessed 2hr (d) or 24 hr (a-c) after training, as described in Fig. 2.

Discussion

mTORC2 regulates actin polymerization-dependent long-term in synaptic strength and memory

Changes in actin dynamics are required for long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation8-10. Although changes in synaptic actin dynamics are thought to occur during learning, how the synaptic actin cytoskeleton controls memory storage remains poorly understood. Our findings reveal that the recently discovered mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) bidirectionally controls the actin polymerization that is required for the conversion of a short-term synaptic process (E-LTP, STM) into a long-lasting one (L-LTP, LTM). Specifically, we found that genetic inhibition of mTORC2 activity blocks actin polymerization, actin regulatory signaling (Fig. 4) and selectively suppresses LTM and L-LTP (Fig. 1 and 2). Conversely, activation of mTORC2 by A-443654 promotes actin polymerization, actin signaling and enhanced L-LTP and LTM in WT mice (Fig. 6a-c and Fig. 7a-b) but not in mTORC2-deficient mice (Fig. 6d-f and Fig. 7c).

More importantly, restoring pharmacologically actin polymerization in mTORC2-deficient mice reverses the impaired L-LTP and LTM (Fig. 5b, 5d). We speculate that the stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton in mTORC2-deficient neurons leads to a morphological reorganization of the synapse which, in response to activity, could facilitate the trafficking and insertion of AMPA receptors clustered at the Postsynaptic Density (PSD). Consistent with this notion, structural plasticity was found to be altered in mTORC2-deficient hippocampal neurons (Fig. 4l). Alternatively, the restoration of actin dynamics in mTORC2-deficient synapses could induce a functional rather than a morphological change as AMPA receptors insertion in the hippocampus during LTP might occur independently of changes in spine shape39. Another interesting possibility is that changes in actin remodeling could regulate changes in gene expression at synapses which are required for L-LTP and LTM (see below).

Other lines of evidence further support the hypothesis that mTORC2 promotes long-term changes in synaptic strength by promoting actin polymerization. First, L-LTP induction is associated with an increase in the F-actin/G-actin ratio40-42 as well as with changes in synaptic morphology and actin signaling43. Second, inhibitors of actin polymerization block the late-phase of LTP, leaving the early phase of LTP intact44-46. Consistent with these data, only stimulation that induces a stable L-LTP reliably increases F-actin at spines45. Third, direct activation of actin polymerization by JPK converts E-LTP into L-LTP and enhances LTM (Fig. 5g-h). Fourth, the disruption of actin filaments in CA1 impairs the consolidation of contextual fear LTM47. Fifth, inhibition of actin polymerization and/or actin regulatory protein signaling in the lateral amygdala blocks auditory fear LTM but not STM48,49. Finally, mTORC2 is activated during learning (Fig. 2a-c), but only by protocols that induce late-LTP (Fig. 1d-f).

Temporal and structural aspects of LTP and memory consolidation: protein synthesis vs. actin cytoskeleton polymerization

According to the prevailing view of memory consolidation, LTM is distinguished from STM by its dependence on protein synthesis1-7. Consequently, all the “molecular switches” identified so far are transcription or translation factors that regulate gene expression (from CREB50 to eIF2α51 to Npas452). However, like protein synthesis, mTORC2-mediated actin polymerization determines whether synaptic and memory processes remain transient or become consolidated in the brain. The evolutionary conservation of this new model, indicated by our comparable findings in Drosophila (Fig. 3), also suggests that our findings may be relevant to the study of memory consolidation in higher mammals, including humans.

Whether actin-mediated changes in synaptic strength depend on, or are perhaps triggered by, changes in gene or protein expression is not immediately clear. Nevertheless, a step towards clarifying the link between actin polymerization and protein synthesis during L-LTP is the finding that actin polymerization, triggered by LTP-inducing stimulation, induces the synthesis of the PKMzeta53, a kinase necessary for the maintenance of L-LTP54. In agreement with these data, we found that the JPK-facilitated L-LTP induced by one tetanic train was blocked by anisomycin (Supplementary Fig. 8a). These results support the idea that actin polymerization is up-stream of protein synthesis. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that protein synthesis and actin polymerization are parallel processes during L-LTP and LTM. Another intriguing possibility is that changes in actin polymerization could directly affect changes in gene expression. For example, actin polymerization promotes the shuttling of the myocardin-related transcription factor (MRTF) protein MKL to the nucleus where it interacts with the Serum Response factor (SRF), thus inducing activity-dependent gene expression in neurons55,56. Alternatively, incorporation of G-actin into F-actin filaments could alter local translation at synapses, by modulation the trafficking of ribosomes, translation initiation factors, RNA bindings proteins or even specifics mRNAs57. If so, the facilitated L-LTP induced by promoting actin polymerization should be insensitive to transcriptional inhibitors.

Our results suggest that neurons have evolved a remarkable bimodal strategy that allows them to control L-LTP and LTM storage both temporally (through regulation of protein synthesis) and structurally (through control of actin dynamics). In this respect, given that mTOR regulates two key processes of L-LTP and LTM - namely mTORC1-mediated protein synthesis3,5 and mTORC2-mediated actin cytoskeleton dynamics - we propose that mTOR is a key regulator of memory consolidation, controlling “distinct” aspects, the temporal through mTORC1 and the structural through mTORC2.

Dysregulation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling appears to have a crucial role in memory disorders, such as the cognitive deficit associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Interestingly, the activity of mTORC2 is altered in the brain of ASD-patients harboring mutations in PTEN and/or TSC1/2 (two upstream negative regulators of mTORC1)58,59. In addition, in PTEN and TSC2 ASD-mouse models, prolonged rapamycin treatment in vivo, which indeed ameliorates the ASD-like phenotypes and restores mTORC1 activity, also corrects the abnormal mTORC2 activity23,60. Our new findings that mTORC2 plays a crucial role in memory consolidation raises the intriguing possibility that the neurological dysfunction in ASD is caused by dysregulation of mTORC2 rather than mTORC1 signaling.

In conclusion, our study not only helps to define key basic cellular and molecular mechanisms of physiological learning and memory but it points towards a new therapeutic approach to the treatment of human memory dysfunction in cognitive disorders or even aging, in which mTORC2 activity is known to be abnormally low.

Methods

Methods and supplemental figure legends are available in the online supplementary material of the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Magnuson, I. Dragatsis and K. Tolias who generously provided rictor/floxed mice, αCaMKII-Cre mice and the Tiam1’s constructs, respectively. We also thank A. Placzek and W. Sossin for comments on an early version of the manuscript. This work was supported by funds to M. C-M (NIMH 096816, NINDS 076708, Searle award grant 09-SSP-211 and Whitehall award).

References

- 1.Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294:1030–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGaugh JL. Memory--a century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–51. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational Control of Long-Lasting Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis HP, Squire LR. Protein synthesis and memory: a review. Psychol Bull. 1984;96:518–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter JD, Klann E. Making synaptic plasticity and memory last: mechanisms of translational regulation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1–11. doi: 10.1101/gad.1735809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SH, Morris RG. Hippocampal-neocortical interactions in memory formation, consolidation, and reconsolidation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2010;61:49–79. C1–4. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Govindarajan A, Tonegawa S. Translational regulatory mechanisms in persistent forms of synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2004;44:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cingolani LA, Goda Y. Actin in action: the interplay between the actin cytoskeleton and synaptic efficacy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:344–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamprecht R, LeDoux J. Structural plasticity and memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:45–54. doi: 10.1038/nrn1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch G, Rex CS, Gall CM. LTP consolidation: substrates, explanatory power, and functional significance. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh WJ, Jacinto E. mTOR complex 2 signaling and functions. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2305–16. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.14.16586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guertin DA, et al. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:859–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiota C, Woo JT, Lindner J, Shelton KD, Magnuson MA. Multiallelic disruption of the rictor gene in mice reveals that mTOR complex 2 is essential for fetal growth and viability. Dev Cell. 2006;11:583–9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carson RP, Fu C, Winzenburger P, Ess KC. Deletion of Rictor in neural progenitor cells reveals contributions of mTORC2 signaling to tuberous sclerosis complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siuta MA, et al. Dysregulation of the norepinephrine transporter sustains cortical hypodopaminergia and schizophrenia-like behaviors in neuronal rictor null mice. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cybulski N, Hall MN. TOR complex 2: a signaling pathway of its own. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:620–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin RJ, et al. Activation of Akt/PKB, increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates and loss and altered distribution of Akt and PTEN are features of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Neurochem. 2005;93:105–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humbert S, et al. The IGF-1/Akt pathway is neuroprotective in Huntington’s disease and involves Huntingtin phosphorylation by Akt. Dev Cell. 2002;2:831–7. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malagelada C, Jin ZH, Greene LA. RTP801 is induced in Parkinson’s disease and mediates neuron death by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation/activation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14363–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3928-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meikle L, et al. Response of a neuronal model of tuberous sclerosis to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors: effects on mTORC1 and Akt signaling lead to improved survival and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5422–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0955-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma A, et al. Dysregulation of mTOR signaling in fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2010;30:694–702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3696-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siarey RJ, et al. Altered signaling pathways underlying abnormal hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1266–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S. CaMKIIalpha-Cre transgene expression and recombination patterns in the mouse brain. Genesis. 2000;26:133–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<133::aid-gene10>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsien JZ, et al. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87:1317–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:307–18. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:633–43. doi: 10.1038/nrm2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris RG, Garrud P, Rawlins JN, O’Keefe J. Place navigation impaired in rats with hippocampal lesions. Nature. 1982;297:681–3. doi: 10.1038/297681a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hietakangas V, Cohen SM. Re-evaluating AKT regulation: role of TOR complex 2 in tissue growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:632–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.416307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tully T, Preat T, Boynton SC, Del Vecchio M. Genetic dissection of consolidated memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:35–47. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holzinger A. Jasplakinolide: an actin-specific reagent that promotes actin polymerization. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;586:71–87. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-376-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han EK, et al. Akt inhibitor A-443654 induces rapid Akt Ser-473 phosphorylation independent of mTORC1 inhibition. Oncogene. 2007;26:5655–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopec CD, Li B, Wei W, Boehm J, Malinow R. Glutamate receptor exocytosis and spine enlargement during chemically induced long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2000–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3918-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukazawa Y, et al. Hippocampal LTP is accompanied by enhanced F-actin content within the dendritic spine that is essential for late LTP maintenance in vivo. Neuron. 2003;38:447–60. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamoto K, Nagai T, Miyawaki A, Hayashi Y. Rapid and persistent modulation of actin dynamics regulates postsynaptic reorganization underlying bidirectional plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1104–12. doi: 10.1038/nn1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen LY, Rex CS, Casale MS, Gall CM, Lynch G. Changes in synaptic morphology accompany actin signaling during LTP. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5363–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0164-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim CH, Lisman JE. A role of actin filament in synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4314–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04314.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kramar EA, Lin B, Rex CS, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrin-driven actin polymerization consolidates long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5579–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krucker T, Siggins GR, Halpain S. Dynamic actin filaments are required for stable long-term potentiation (LTP) in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6856–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100139797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Schrick C, Spiess J, Radulovic J. Distinct roles of hippocampal de novo protein synthesis and actin rearrangement in extinction of contextual fear. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1962–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5112-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamprecht R, Farb CR, LeDoux JE. Fear memory formation involves p190 RhoGAP and ROCK proteins through a GRB2-mediated complex. Neuron. 2002;36:727–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mantzur L, Joels G, Lamprecht R. Actin polymerization in lateral amygdala is essential for fear memory formation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bourtchuladze R, et al. Deficient long-term memory in mice with a targeted mutation of the cAMP-responsive element-binding protein. Cell. 1994;79:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costa-Mattioli M, et al. eIF2alpha phosphorylation bidirectionally regulates the switch from short- to long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2007;129:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramamoorthi K, et al. Npas4 regulates a transcriptional program in CA3 required for contextual memory formation. Science. 2011;334:1669–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1208049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly MT, Crary JF, Sacktor TC. Regulation of protein kinase Mzeta synthesis by multiple kinases in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3439–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5612-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sacktor TC. How does PKMzeta maintain long-term memory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:9–15. doi: 10.1038/nrn2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalita K, Kuzniewska B, Kaczmarek L. MKLs: co-factors of serum response factor (SRF) in neuronal responses. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:1444–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Olson EN, Nordheim A. Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:353–65. doi: 10.1038/nrm2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Horck FP, Holt CE. A cytoskeletal platform for local translation in axons. Sci Signal. 2008;1:pe11. doi: 10.1126/stke.18pe11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ljungberg MC, et al. Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin in cytomegalic neurons of human cortical dysplasia. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:420–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knobbe CB, Trampe-Kieslich A, Reifenberger G. Genetic alteration and expression of the phosphoinositol-3-kinase/Akt pathway genes PIK3CA and PIKE in human glioblastomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:486–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou J, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 suppresses anatomical, cellular, and behavioral abnormalities in neural-specific Pten knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1773–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5685-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferris J, Ge H, Liu L, Roman G. G(o) signaling is required for Drosophila associative learning. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1036–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tolias KF, et al. The Rac1-GEF Tiam1 couples the NMDA receptor to the activity-dependent development of dendritic arbors and spines. Neuron. 2005;45:525–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.