Over the past decade, research and clinical interest in the therapeutic effectiveness of exercise after cancer diagnosis has greatly increased.1 Positive findings from the first generation of exercise oncology studies, and growing patient demand led the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) to assemble an expert panel to formulate exercise guidelines for patients with cancer.2 This comment presents a practical approach to screening and prescribing exercise for patients with cancer.

Systematic reviews indicate that exercise is a safe, well-tolerated intervention for patients with curative disease, both during and after adjuvant therapy.3 However, patients with cancer are often older, have a range of comorbid diseases, and receive a diverse range of locoregional and systemic cytotoxic therapies that could increase the risk of exercise-related complications, particularly in sedentary individuals. By incorporating formalised pre-exercise screening into standard practice, oncologists can provide safe and more accurate exercise guidance for patients. A careful history and physical examination of cardiac, pulmonary, neurological, and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms can be used to assess the safety of exercise in patients, or the need for further evaluation. Procedures such as the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire or PARmed-X can facilitate the screening process. Patients at moderate or high-risk and those with a positive initial screen should be referred for a symptom-limited exercise stress testing with electrocardiograph diagnostics.

ACSM guidelines recommend that patients with cancer should participate in at least 150 min of moderate exercise (eg, brisk walking, light swimming) or 75 min per week of vigorous exercise (eg, jogging, running, hard swimming).2 However, this recommendation is a long-term goal and is not advised as an initial prescription for most sedentary patients either during or immediately after cytotoxic therapy. The key to safe and effective exercise prescriptions is individualisation of the programme to patients’ needs. Providing cancer patients with individually tailored exercise prescriptions is challenging given the considerable variation in pathophysiology, therapeutic management, and prognosis between malignancies and individual patients. Nevertheless, individualised prescriptions can be provided in most scenarios if the fundamental principles of exercise prescription are followed: frequency (sessions per week), intensity (how hard per session), time (session duration), and type (exercise modality)—or the F.I.T.T principle.

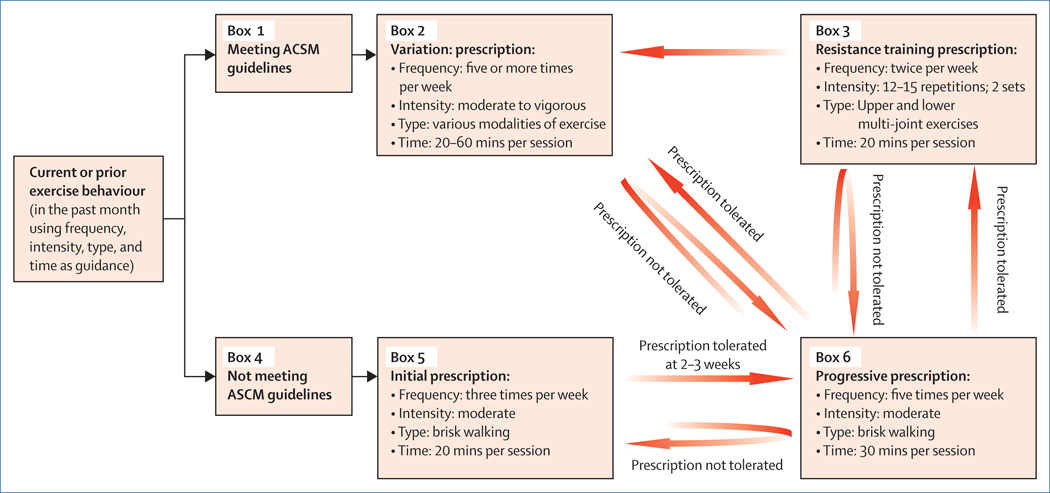

For individualised exercise prescriptions (figure), the first question should focus on present exercise behaviour. Patients who meet the ACSM guidelines can maintain present behaviour, but 150 min of moderate or 75 min of vigorous exercise per week should be the minimal amount of exercise needed to gain health benefits. Increases in exercise beyond these minimal amounts can lead to further health benefits. Such benefits can be achieved by varying the intensity, frequency, duration, and type of exercise every 2–3 weeks to reduce boredom and ensure continuous improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness. For sedentary patients or those who do not meet the ACSM guidelines, the figure presents a progressive exercise prescription that can be discussed in routine clinical visits. Whether one type of exercise is more effective than another at improving exercise tolerance or symptoms in patients with cancer is not known. Walking is often the preferred choice for most patients, although stationary cycling might be more appropriate for older patients and those who have gait or coordination difficulties. Prescription of the appropriate intensity of exercise is challenging. Intensity of exercise can be explained practically to patients with the talk-test whereby moderate exercise is activity during which one can comfortably hold a conversation, and vigorous exercise is defined as activity that precludes comfortable conversation. More accurate methods are available that use ratings for perceived exertion or heart-rate training zones. Such training zones can be calculated with either age-sex-predicted equations or, preferably, heart-rate responses obtained from the exercise stress test. The addition of resistance training to comprehensive exercise prescription is crucial to increase muscle mass and prevent deterioration in all patients with cancer. The decision of when to include resistance training in the exercise prescription depends on the patient’s needs. In patients with cancer or treatment-related cachexia, or in those whose aerobic exercise is contraindicated, resistance training should be the central focus. In other scenarios, however, it might be more appropriate to start resistance training once aerobic training is part of a patient’s habitual activity.

Figure. A general approach to individualised exercise prescriptions4.

Patients who meet the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines (ie, ≥150 min per week of moderate or ≥75 min per week of vigorous exercise [Box 1]) should be encouraged to either maintain (eg, if undergoing therapy) or preferably increase exercise levels, by varying the frequency, intensity, type, and time of exercise every 2–3 weeks (Box 2). Resistance training should be recommended to patients once aerobic training is part of habitual activity (Box 3). Patients who do not follow the ACSM guidelines (Box 4) should be recommended to complete an introductory prescription as described (Box 5). If adequately tolerated, the patient can increase the frequency and duration of exercise until more than 150 min per week of moderate exercise is achieved (Box 6). In patients who maintain exercise behaviour that is consistent with ACSM guidelines for more than 12 weeks, resistance training and exercise variation (Box 2) should be added to the prescription (Box 3). Adapted from reference 4.

In summary, findings indicate that sedentary behaviour and decreased exercise levels are associated with de-conditioning, poor symptom control, and possibly a poor clinical outcome after cancer diagnosis. Exercise tolerance and several patient-reported outcomes can be improved with structured exercise training across a range of oncological settings. Oncology professionals have a considerable influence on the levels of patient exercise5 and we emphasise the importance of exercise counselling with frequent follow-up whenever appropriate. The ASCM exercise guidelines represent a major benchmark in exercise-oncology research and oncology management. The steps that we describe can help oncology professionals to integrate exercise therapy into their practice. Advancements in the field will continue to modify and refine these guidelines to ensure optimum safety and efficiency of exercise for patients with cancer.

Acknowledgments

LWJ was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA143254, CA142566, CA138634, CA133895, CA125458) and funds from George and Susan Beischer. JP is supported by the American Society of Clinical Oncology Foundation, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Greenwall Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jones LW, Peppercorn J. Exercise research: early promise warrants further investment. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:408–410. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. for the American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metkus TS, Jr, Baughman KL, Thompson PD. Exercise prescription and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;121:2601–2604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.903377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, Mackey JR. Effects of an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behaviour in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:105–113. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]