Abstract

Due to unfavorable lifestyle habits (unhealthy diet and tobacco abuse) the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in western countries is increasing. The GERD-Barrett-Adenocarcinoma sequence currently lacks well-defined diagnostic, progressive, predictive, and prognostic biomarkers (i) providing an appropriate screening method identifying the presence of the disease, (ii) estimating the risk of evolving cancer, that is, the progression from Barrett's esophagus (BE) to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), (iii) predicting the response to therapy, and (iv) indicating an overall survival—prognosis for EAC patients. Based on histomorphological findings, detailed screening and therapeutic guidelines have been elaborated, although epidemiological studies could not support the postulated increasing progression rates of GERD to BE and EAC. Additionally, proposed predictive and prognostic markers are rather heterogeneous by nature, lack substantial proofs, and currently do not allow stratification of GERD patients for progression, outcome, and therapeutic effectiveness in clinical practice. The aim of this paper is to discuss the current knowledge regarding the GERD-BE-EAC sequence mainly focusing on the disputable and ambiguous status of proposed biomarkers to identify promising and reliable markers in order to provide more detailed insights into pathophysiological mechanisms and thus to improve prognostic and predictive therapeutic approaches.

1. Introduction

In western countries, the particular importance of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as a main risk factor for Barrett's esophagus (BE) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) promoted by obesity, hiatus hernia, and tobacco use has increased constantly [1, 2]. Chronic injury of the gastro-esophageal junction by gastric acid or bile juice induces and promotes initially reversible metaplastic changes of the squamous epithelia which is confirmed by endoscopic examination and histomorphology [3–7]. The classical GERD-BE-EAC sequence postulates a stepwise progression over different stages of dysplasia [8, 9]. However, the postulated consecutive sequence during cancerogenesis of BE has not been proven up to now [10]. Reid et al. characterized this issue as “the paradox of Barrett's esophagus,” pointing out that the majority of EACs (95%) arise without prior diagnosis of BE or GERD which possibly indicates that steps of the proposed linear BE-EAC development are skipped. Nevertheless, consequent surveillance of patients with GERD and concomitant BE within well-defined time intervals with biopsy of suspicious lesions may prevent dysplasia—caused by epithelial injuries due to GERD—from developing into invasive cancer.

Although no increase of EAC incidence was postulated in epidemiologic studies, about 5% of patients with GERD and 0.5% with BE developed EAC [2, 11–13].

As dysplasia and adenocarcinoma are diagnosed by pathologists routineously (based on Haematoxylin-Eosin-stained biopsies), the question arises how the “risk progression” of GERD to BE and further to dysplasia and EAC can be evaluated and predicted by prognostic molecular markers and ideally may predict therapeutic success. In this paper, we try to refer to these FAQs and to provide a panel of diagnostic and predictive markers.

2. Definition of GERD, BE, EAC, and Types of Requested Prognostic and Predictive Markers

(i) GERD describes the chronic reflux of gastric acid or bile fluid to the esophagus resulting in metaplastic changes of the normal squamous esophageal tissue to columnar epithelium (BE) (for review, see [5]). The metaplastic changes—assessed by upper endoscopy and histological approval—comprise proximal columnar epithelia with intestinal type goblet cells, the junctional (cardial) subtype with mucous secreting glands and the gastric fundus subtype with parietal and chief cells [7, 14]. Up to now, a uniform definition of Barrett's esophagus (BE) remains controversial (e.g., which type of metaplastic changes qualifies the diagnosis BE?) leading to the striking statement “no goblets, no Barrett's” [4, 5], disregarding that nongoblet elements may also be involved in the malignant transformation of BE assessed by Sucrase-Isomaltase and dipeptidyl peptidase IV protein expression [15].

Whereas the detection of intestinal goblet cells in BE samples is already established by using histochemical staining like Alcian-PAS, the diagnosis of dysplasia in BE remains a great challenge due to inter- and intraobserver variation in histology grading (discussed later); therefore, the incidence of dysplasia inside BE varies from 5, to 10% according to national screening efforts and surveillance programs [16]. While diagnostic criteria of BE with dysplasia are relatively well defined by combining cytological and architectural changes, their prospective validation is still missing (for details, see [17–21]).

Moreover, diagnosis of the progression from BE with dysplasia to invasive EAC becomes sometimes impracticable when biopsies are small and criteria of invasiveness are mimicked by distorted rearrangement of glandular structures caused by ulceration and inflammation. At present, using the grade of dysplasia in BE represents the best biomarker in predicting the progression probability for nondysplastic BE (about 0.5%), low-grade dysplasia in BE (13%), and up to 40% in high-grade dysplasia in BE [22, 23]. Therefore, screening surveillance of BE and dysplasia remains still important to detect precursor lesions of EAC in order to avert the disastrous fate of progressive EAC which is characterized by an overall 5-year survival rate between 3.7% and 15.6% [24].

(ii) Complexity factor “diagnosis”: Several issues in BE as well as in EAC detection are still unsolved. The majority of patients with BE remain undiagnosed [25–28], and/or patients with BE and dysplasia are often mis- or overdiagnosed due to inter- and intra-observer errors [10, 29, 30]. Based on the low progression rate of BE to EAC [11], endoscopic and bioptic surveillance studies could not convey a significant benefit for controlled patients [31]. Therefore, the demand for reliable biomarkers regarding prognosis and prediction of patients with BE without/with dysplasia as well as with EAC still remains indispensable.

(iii) Definition of predictive and prognostic factors (for reviews, see [32–34]): The widely used term “biomarker” represents a marker for physiological or pathological processes or therapeutic response. The clinical characteristics or endpoints (like patient performance status or disease-free period) which should be achieved by these biomarkers as well as methods applied (e.g., genome, transcriptome, proteome, or metabolome) are rather heterogeneous. The term “predictive factor” refers to the use as biomarker for prediction of the statistical probability of disease recurrence, metastasis, or tumor-related death as well as for prediction of specific therapeutic effectiveness.

As recommend by Pepe et al. [35] and McShane et al. [36], different and clearly defined “milestones” must be passed during biomarker development to evaluate their clinical prognostic and predictive potentials: starting with data obtained from experimental cell culture up to retrospective and prospective validation studies resulting in clinical applicability and significant decreasing mortality, and completed by increasing health and cost benefits.

3. “Classical” Genetic and Molecular Alterations in GERD, BE, and EAC

During carcinogenesis of BE to EAC, heterogeneous hallmarks of molecular changes are described in the literature [8, 37, 38].

(a) Genetic abnormalities of BE include loss of genetic information (especially loss of 9p21, 5q, 13q, 17p, and 18q), whereas for progressive disease, a more extensive imbalance including gain of genetic information (especially gain of 2p, 8q, and 20q) is observed. Finally, enhanced chromosomal instability could be found in the progressive lesions of EAC.

(b) These genetic abnormalities cause consecutive deregulations of their products like tumor suppressor genes (p53 (loss of 17p), p16 (loss of 9p21), fragile histidine triad protein (FHIT), adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) (loss of 5q), retinoblastoma (Rb) (loss of 13q)), cell cycle regulatory factors (cyclin D1 and MDM2 (mouse double minute 2 homolog)), growth factor receptors (EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), TGF-α (transforming growth factor)), c-erbB2 and cell adhesion molecules (E- and P-Cadherin and α- and β-Catenin), as well as proteases (uPA, urokinase-type plasminogen activator) according to the hallmarks of cancer [39]. Additionally, molecular alterations are associated with epigenetic changes such as the methylation and acetylation status as known for APC [40] and p16 [41].

(c) Distinct changes in expression pattern of various miRNAs (microRNA) have been demonstrated in BE or EAC. miRNAs are small regulative noncoding RNA molecules (18–22mer) which inhibit the expression of their target genes on posttranscriptional levels; about 30% of human genes are estimated to be regulated by miRNAs [42].

Using global miRNA expression profiling or in situ hybridization, several miRNAs (miR-143, -199a_3p, -199a_5p, -100, -99a [43], miR-16-2, -30E, and -200a [44]) have been identified whose expression was associated with reduced overall survival in EAC [43, 44]. A more detailed insight into the relevance of different miRNA expression has been provided recently by Leidner et al. [45] in n = 20 EAC samples; next generation sequencing and qRT-PCR identified a total of 26 miRNA that are deregulated in EAC more than 4-fold in >50% of cases compared to normal esophageal squamous tissue. After laser microdissection-based comparison between the steps of BE-EAC-sequence, two miRNAs (miR-31 and -31*) were downregulated in high-grade dysplasia and EAC cases, thus implicating an association with the transition from BE to HGD lesions. Another miRNA (-375) was exclusively down-regulated in EAC, whereas BE and HGD lesions showed normal expression. In a 5-year follow-up study, a different set of miRNAs (miR-192, -194, -196a, and -196b) could be identified in BE samples with progression to EAC compared to patients who did not progress to EAC [46]. The relevance of miRNA-196a as molecular markers associated with the progression from intestinal metaplasia to EAC has also been demonstrated earlier by Luzna et al. [47].

Recently, a link between EMT and miRNA expression in BE or EAC was established in both: Barrett's epithelia and EAC displayed a reduced expression of miRNA-200 family members [108]. These miRNAs take a central position in regulation of the initial step of metastasis by inhibiting the EMT effector transcription factors ZEB-1 and -2 [109].

Taken together, the relevance of miRNA for prognosis and progression of BE and EAC is being unveiled in current research. Final statements require additional studies using independent patient cohort—also with higher case-load—accompanied by functional verification [43, 110].

4. Predictive and Prognostic Factors for GERD, BE, and EAC?

Previous reviews already discussed the importance of biomarkers in this area and proclaimed further investigations thereof in gastroenterological oncology (for review, see Ong et al. [111], Fang et al. [112], and Huang and Hardie [113]). Usually, biomarkers are classified as markers for risk evaluation in patients with GERD to develop EAC or as biomarkers for predictive and prognostic evaluation in patients with diagnosed EAC. Hence, the presented data implicate—and pretend—that we have already reached “the end of the road” with available and significant biomarkers. However, detailed assessment and comparison with other cancers, such as breast, prostate, as well as colorectal [114], reveal them in a rather disillusioning light. Since endoscopic-bioptic surveillance studies yielded no significant benefit for BE patients [31], and prognosis of patients with EAC still is disastrous [24], further intensive experimental and clinical research of (molecular) pathological mechanisms are required urgently.

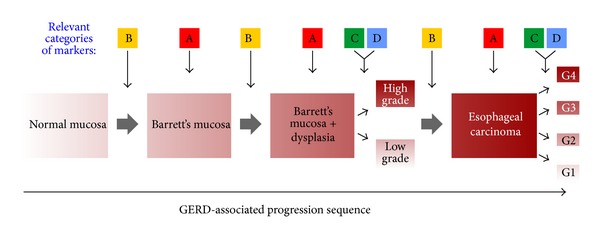

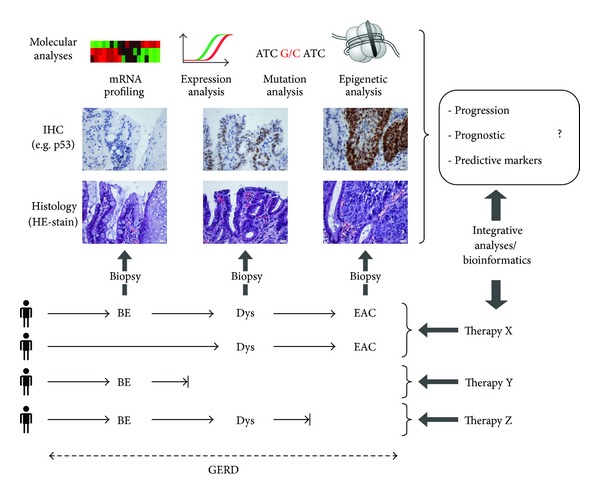

Based on studies regarding potential predictive and prognostic markers within the GERD-BE-EAC sequence, we classified them into four groups (Table 1 and Figure 1) and illustrated a patient-specific disease sequence (Figure 2; for details, see reviews [111–113, 115]): (A) diagnostic biomarkers—indicate the presence of disease, (B) progression biomarkers—indicate the risk of developing cancer, that is, progression from BE to EAC, (C) predictive biomarkers—predict response to therapy, and (D) prognostic biomarkers—indicate overall survival, that is, prognosis for EAC.

Table 1.

Summary of investigated and published biomarkers in the GERD-BE-EAC axis. The categorization is based on four groups according to their potential usage as A = Diagnostic Biomarker indicates the presence of disease, B = Progression Biomarker indicates the risk of developing cancer—progression in BE to EAC, C = Predictive Biomarker predicts response to therapy (CTX, RTX, photodynamic therapy), or D = Prognostic Biomarker indicates overall survival—prognostic in EAC (survival, recurrence).

| Biomarker | Method | Remarks/findings | OR/RR/P value | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A = Diagnostic Biomarker | TFF3 | novel nonendoscopic screening modality in a prospective cohort study |

P = 0.02 (for maximal length of BE) P = 0.009 (for circumferential length of BE) |

[48] | |

| TFF3 | IHC, esophageal cytosponge samples for BE combined with IHC for TFF3 | biomarker to screen asymptomatic patients for BE; TFF3 protein was expressed at the luminal surface of BE (not at normal esophageal or gastric mucosa) |

P < 0.0001 | [49] | |

| Chromosomes 7 and 17 (copy number changes) | ICDA & FISH | chromosomal gains in early stages of BE; valuable adjunct to conventional cytology to detect dysplasia or EAC |

IND/LGD: 75% sensitivity, (76% specificity) HGD/EAC: 85% sensitivity, (84% specificity) |

[50] | |

| 8q24 (C-MYC), 17q12 (HER2), and 20q13 (copy number changes) | FISH | chromosomal gains in early stages of BE; represents a valuable adjunct to conventional cytology to detect dysplasia or EAC |

LGD (50% sensitivity) HGD (82% sensitivity) EAC (100% sensitivity) |

[51] | |

| 17q11.2 (ERBB2) | Southern blotting, microarray analysis | amplified copies of the ERBB2 gene in EAC | 10-fold amplification in 3 of 25 (12%) tumors | [52] | |

| Serum proteomic pattern analysis | mass spectrometry | several limitations due to applied technology | identified 10 of 11 normal's; and 42 of 43 EAC's correctly | [53] | |

|

| |||||

| B = Progression Biomarkers | P53 positivity | IHC | limited efficacy as a single progression biomarker | OR 11.7 (95% CI: 1.93–71.4) | [54] |

| P53 positivity | IHC | positive in 4/31 that regressed, 3/12 that persisted, and 3/5 that progressed to HGD or EAC | RR not available | [55] | |

| DNA content abnormalities | flow cytometry | higher relative risk for EAC in patients with tetraploidy (4N) or aneuploidy (>6%) | tetraploidy: RR 7.5 (95% CI: 4–14) (P < 0.001) aneuploidy: RR 5.0 (95% CI: 2.7–9.4) (P < 0.001) |

[56] | |

| 4N fraction cut point of 6% for cancer risk | RR 11.7 ( 95% CI: 6.2–22) | ||||

| aneuploid DNA contents of 2.7N were predictive of higher cancer risk | RR 9.5 (95% CI: 4.9–18) | ||||

| DNA content abnormalities | flow cytometry | presence of both 4N fraction of 6% and aneuploid DNA content of 2.7N is highly predictive for progression | RR 23 (95% CI: 10–50) | [57] | |

| 17p(p53) LOH associated with higher risk of progression to HGD + EAC | HGD: RR 3.6 (P = 0.02) | ||||

| flow cytometry, PCR | EAC: RR 16 (P < 0.001) | [58] | |||

| combined LOH of 17p and 9p and DNA content abnormalities can best predict progression to EAC | RR 38.7 (95% CI: 10.8–138.5) not clinical applicable | ||||

| LOH of 157p and 9p and DNA content abnormalities | LOH of 17p alone | RR 10.6 (95% CI: 5.2–21.3) | |||

| flow cytometry, PCR | LOH of 9p alone | RR 2.6 (95% CI: 1.1–6.0) | |||

| Aneuploidy alone | RR 8.5 (95% CI: 4.3–17.0) | [59] | |||

| Tetraploidy alone | RR 8.8 (95% CI: 4.3–17.7) | ||||

| mutations of p16 and p53 loci (clonal diversity measurements) | flow cytometry, PCR | significant predictors for EAC progression, not clinical applicable | P = 0.001 | [60] | |

| EGFR | IHC | overexpression in HGD/EAC | 35% of HGD/80% of EAC specimens | [61] | |

| MCM2 | IHC | correlation between degree of dysplasia and level of ectopic luminal surface MCM2 expression | MCM2-positive staining in 42% (19/45) of BE samples |

[62] | |

| Cyclin A | IHC | surface expression of cyclin A in BE samples correlates with the degree of dysplasia | OR 7.5 (95% CI: 1.8–30.7) (P = 0.016) | [63] | |

| Cyclin D1 | IHC | association with increased risk of EAC | OR 6.85 (95% CI: 1.57–29.91) | [64] | |

| hypermethylation of p16 (CDKI2A) | association with increased risk of progression to HGD/EAC | OR 1.74 (95% CI: 1.33–2.2) | |||

| hypermethylation of RUNX3 | association with increased risk of progression to HGD/EAC | OR 1.80 (95% CI: 1.08–2.81) | |||

| hypermethylation of HPP1 | RT-PCR | association with increased risk of progression to HGD/EAC | OR 1.77 (95% CI: 1.06–2.81) | [41] | |

| hypermethylation of p16 and APC | PCR | predictor of progression to HGD/EAC | OR 14.97 (95% CI: 1.73–inf.) | [65] | |

| 8 gene methylation panel | RT-PCR | age dependent; predicts 60.7% of progression to HGD/EAC within 2 yrs | RR not available (90% specificity) | [66] | |

| Gene expression profile | microarray analysis | 64 genes up regulated 110 genes down regulated in EAC |

P = 0.05 | [67] | |

| Cathepsin D, AKR1B10, and AKR1C2 mRNA levels | Western blotting, qRT-PCR | dysregulation predicts progression to HGD/EAC | AKR1C2: ↑ levels in BE (P < 0.05) but ↓ levels in EA (P < 0.05) |

[68] | |

| ICDA | aneuploidy predicts progression to EAC | 60% with LGD; 73% with HGD, and 100% with EAC (total number of samples = 56) | [69] | ||

| DNA abnormalities | ACIS | frequency and severity of aneuploidy predicts progression to EAC | unstable aneuploidy in 95% with EAC | [70] | |

| DICM | relationship between DICM status and progression to HGD/EAC | P < 0.0001 | [71] | ||

| SNP-based genotyping in BE/EAC specimens | flow cytometry, 33K SNP array | copy gains, losses, and LOH increased in frequency and size between early and late stage of disease | P < 0.001 (BE) | [72] | |

|

| |||||

| C = Predictive Biomarkers | p16 allelic loss | FISH | decreased response to photodynamic therapy | OR 0.32 (95% CI: 0.10–0.96) | [73] |

| DNA ploidy abnormalities | ICDA | DNA ploidy as a covariate value for recurrence | HR 6.3 (1.7–23.4) (P < 0.0015) | [74] | |

| HSP27 | IHC | association between low HSP27 expression and no response to neoadjuvante chemotherapy | P = 0.049 and P = 0.032 | [75] | |

| Ephrin B3 receptor | microarray | response prediction in EAC in patients with Ephrin B3 receptor positive versus Ephrin B3 receptor negative | Response rate <50%: 3 (15.8) versus 16 (84.2) (P < 0.001) | [76] | |

| Genetic polymorphisms | qRT-PCR | association between individual single nucleotide polymorphisms and clinical outcomes |

comprehensive panel of genetic polymorphisms on clinical outcomes in 210 esophageal cancer patients | [77] | |

| P21 | IHC | alteration in expression correlated with better CTX-response | P = 0.011 | [78] | |

| P53 | IHC | alteration in expression correlated with better CTX-response | P = 0.011 | [79] | |

| ERCC1 | IHC | ERCC1-positivity predicts CTX-resistance and poor outcome | P < 0.001 | [80] | |

|

| |||||

| D = Prognostic Biomarkers | DCK PAPSS2 SIRT2 TRIM44 |

RT-PCR, IHC |

prognostic 4-gene signature in EAC predicts 5-year survival | 0/4 genes dysregulated: 58% (95% CI: 36%–80%) 1-2/4 genes dysregulated: 26% (95% CI: 20%–32%) 3-4/4 genes dysregulated: 14% (95% CI: 4%–24%) (P = 0.001) |

[81] |

|

p16 loss C-MYC gain |

FISH | association between therapy response status and FISH positivity | P = 0.04 | [82] | |

| ASS expression | microarrays | low expression correlates with lymph node metastasis | P = 0.048 | [83] | |

| microRNA expression profiles | miRNA microarray, qRT-PCR | association with prognosis (e.g. low levels of mir-375 in EAC → worse prognosis) | HR = 0.31 (95% CI: 0.15–0.67) (P < 0.005) | [84] | |

| Genomic alterations | MLPA | reverse association between survival and DNA copy number alterations (>12 aberrations → low mean survival) | P = 0.003 | [85] | |

| Cyclin D1 | FISH, IHC | 2 of 3 genotypes confers to ↓ survival | P = 0.0003 | [86] | |

| IHC | expression = ↓ survival | P = 0.07 | [87] | ||

| EGFR | IHC | ↓ expression = ↓ survival | P = 0.034 | [88] | |

| Ki-67 | IHC | low levels of staining (<10%) = ↓ survival |

P = 0.02 | [89] | |

| Her2/neu | FISH | amplification = ↓ survival | P = 0.03 | [90, 91] | |

| IHC | low levels = ↓ survival | P = 0.03 | [92] | ||

| TGF-α | IHC, ISH | high levels = tumor progression and lymph node metastasis | P = 0.025 and P < 0.05 | [93] | |

| qRT-PCR | overexpression = ↓ survival | P = 0.0255 | [94] | ||

| TGF-β1 | ELISA | high plasma levels = ↓ survival | P = 0.0317 | [95] | |

| APC | RT-PCR | high plasma levels of methylation = ↓ survival |

P = 0.016 | [96] | |

| Bcl-2 | IHC | expression = ↓ survival | P = 0.03 | [97] | |

| IHC, RT-PCR | ↑ expression = ↓ survival, ↑ TN-stage, and recurrence |

P < 0.001, P = 0.008/0.049, and P = 0.01 |

[98] | ||

| IHC | strong staining = ↓ survival | P = 0.03 | [99] | ||

| COX-2 | IHC | strong staining = ↓ survival, distant metastasis, and recurrence | P = 0.002, P = 0.02, and P = 0.05 | [100] | |

| NF-κB | IHC | activated NF-κB = ↓ survival, and ↓ disease free survival |

P = 0.015 and P = 0.010 | [101] | |

| Telomerase | Southern blot analysis, RT-PCR | higher telomere-length ratio = ↓ survival |

RR of death: 3.4 (CI: 1.3–8.9) (P < 0.02) |

[102] | |

| expression = ↓ survival, | P < 0.01 | ||||

| CD105 | angiolymphatic invasion | P < 0.05 | |||

| ↑ lymph node metastasis | P < 0.01 | ||||

| ↑ T-stage | P < 0.001 | ||||

| IHC | ↑ distant metastasis | P < 0.01 | [103] | ||

| ↑ expression = ↓ survival, | P < 0.01 | ||||

| VEGF | angiolymphatic invasion | P < 0.05 | |||

| ↑ lymph node metastasis | P < 0.01 | ||||

| ↑ T-stage | P < 0.01 | ||||

| ↑ distant metastasis | P < 0.01 | ||||

| Cadherin | IHC | ↓ level = ↓ survival | P = 0.05 | [89] | |

| uPA | ELISA | ↑ uPA = ↓ survival | P = 0.0002 | [104] | |

| TIMP | IHC, RT-PCR | ↓ expression = ↓ survival, and ↑ disease stage | P = 0.007 and P = 0.046 | [105] | |

| Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes | IHC, methylation specific PCR | if >50% of gene profile methylated = ↓ survival, and earlier recurrence |

P = 0.05 and P = 0.04 | [106] | |

| MGMT hypermethylation | IHC, methylation specific PCR | correlation with higher tumor differentiation | P = 0.0079 | [107] | |

ACIS: automated cellular imaging system; ASS: argininosuccinate synthase; APC: adenomatous polyposis coli; BE: barrett's esophagus; COX: cyclooxygenase; DCK: deoxycytidine kinase; DICM: digital image cytometry; EAC: esophageal adenocarcinoma; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FISH: fluorescence in-situ-hybridization; ICDA: image cytometric DNA analysis; HSP27: Heat-shock protein 27; IHC: immunohistochemistry; LOH: loss of heterozygosity; PAPSS2: 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; qRT: quantitative reverse transcriptase; MLPA: multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; SIRT2: Sirtuin 2; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; TFF3: Trefoil factor 3; TGF: transforming growth factor; TIMP: tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases; TRIM44: Tripartite motif-containing 44; uPA: urokinase-type plasminogen activator; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 1.

GERD-associated progression for Barrett's esophagus (BE) to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). A–D refer to biomarkers which could be most relevant at the indicated stages of the disease progression (according to Table 1). Therefore A, B, C, and D stand for diagnostic, progressive, predictive, and prognostic biomarkers, respectively.

Figure 2.

Proposed approach for identification of novel biomarkers for the GERD-BE-AEC sequence. Based on theheterogeneous and patient-specific progression sequence from BE to EAC, the figure indicates the disease stages and mandatory (histology, IHC) and supplementary potential methods for investigation of putative biomarkers for progression, prediction, and prognosis. These data possibly result in an evidence-based stratification of patients for various available therapies (X–Z) based on a rational selection and evaluation of specific biomarkers. Abbreviations. Esophageal adenocarcinoma: AEC; dysplasia: Dys; fluorescence in-situ hybridization: FISH; gastro-esophageal reflux disease: GERD; immunohistochemistry: IHC.

4.1. A = Diagnostic Biomarkers—Indicate the Presence of Disease

The conventional approach for detection and diagnosis is the histochemical analysis of endoscopically derived biopsies of the gastro-esophageal junction, albeit the proposed importance of histological subtypes, the gastric fundus, the cardiac subtype, and the metaplastic columnar epithelium with intestinal-type goblet cells remains unclear [116]. The relevance of these factors has been discussed for years, but prospective studies clarifying the prognostic ability of these histological subtypes are currently not available. Additionally, the trefoil factor 3 (TFF3) combined with a noninvasive diagnostic technique has been investigated intensively in otherwise asymptomatic BE patients [48, 49]. Their results are promising, possibly enabling a selective screening of patients; however, these findings require independent validation and assessment before further clinical application.

4.2. B = Progression Biomarkers—Indicate the Risk of Progression from BE to EAC

Similar to the situation for diagnostic biomarkers (A), the most frequently applied progression marker for clinicians and pathologists is the degree of dysplasia in obtained biopsies. Although the inter- and intra-observer error [10, 29, 30] is extremely unsatisfying, studies confirmed that high-grade dysplasia is associated with a 40% higher risk for progression of BE to EAC [22, 23]. Therefore, a primary goal should be the standardization of criteria for dysplasia based on conventional Haematoxylin-Eosin-stained specimens in order to avoid under- and overdiagnosis [10, 29, 30]. Several molecular markers are evaluated too (see Table 1)—the most promising ones according to their statistical robustness (based on OR and RR) are MCM2 expression pattern (highest OR of about 136, whereby the confidence interval is large, reducing the potency of this marker). Loss of heterozygosity on distinct gene loci, especially at 17p, indicates a high progression probability from BE to EAC. The expression pattern of P53 as well as the hypermethylation of p16 and APC suggests high potency, followed by the cell-cycle-associated proteins Cyclin A and D1. These markers were intensively evaluated within retrospective studies but did not succeed the direct transfer to clinical practice, especially due to cost- and time-intensive experimental work. In our experience, the immunohistochemical evaluation of P16 and P53 is well established in pathological diagnostics, whereby the quantification and standardization remains still an unsolved problem.

4.3. C = Predictive Biomarkers—Predict Response to Therapy

As displayed in Table 1, the number of potential predictive biomarkers is considerably lower than all other categories accompanied by mainly nonsignificant P values. Additionally, biomarkers of category A such as p53 and p16 are also listed in category C, indicating the overall impact of these biomarkers. In sum, the limited number of available and reliable C-markers must be considered as a starting point for inevitable research in the establishment of reliable predictive biomarkers.

4.4. D = Prognostic Biomarkers—Indicate Overall Survival–Prognostic in EAC

It is not surprising that the majority of biomarkers are listed in the last category—displaying the typical survey of hallmarks of cancer [39] reaching from self-sufficiency in growth signals (Cyclin D1, EGFR, Ki-67, Her2/neu, TGF-α), insensitivity to growth inhibitory signals (TGF-β1, APC, P21), evasion of programmed cell death (Bcl-2, COX-2, NF-κB), limitless replicative potential (Telomerase), sustained angiogenesis (CD105, VEGF), invasion and metastasis (Cadherin, uPA, TIMP), tumor differentiation (MGMT), and cancer-related inflammation (NF-κB, COX-2) (see Table 1). Beside their functional heterogeneity, their applicability for prognosis is uncertain. How to use which markers and when? Should we use a panel of markers? The primary and secondary literature currently gives no further advice to solve this problem. Although high levels of significance could be achieved using these biomarkers (P < 0.001), the practicability and efficiency in daily routine is unknown. This observation is supplemented by the fact that the most applicable approach for prognostic stratification in EAC is based on the TNM system using conventional basic clinical and pathological findings of tumor extension as well as local and distant metastasis in lymph nodes and organs [117]. Therefore, intensive statistical analysis of comprehensive sets of EAC samples accompanied by selected biomarkers must be performed using factor or hierarchical cluster analysis to evaluate the best prognostic combination of biomarkers.

To assemble the sometimes confusing data on possible biomarkers (as listed in Table 1) in one point, the histological confirmation of “dysplasia” seems to be unique indicating the “limitation or limited outcome” of our biomarker repertoire (see Table 2). Nevertheless, we should keep in mind that BE is frequently under- and over-diagnosed resulting in huge inter- and intra-observer errors [10, 29, 30], thus demanding for detailed and decisive morphological criteria. From the set of molecular markers, “only” p53, p16, and p21 currently represent applicable biomarkers, especially for progression. Interestingly, growth factors and cell cycle associated factors are relevant for prognosis, but it seems impossible to highlight one exclusively out of the “myriad” of biomarkers [118].

Table 2.

Synopsis of biomarkers in the GERD-BE-EAC axis. According to Table 1, most promising biomarkers are summarized indicating that only dysplasia is involved in all four categories. Dysplasia can be used as diagnostic biomarker as well as to assess the risk of progression to EAC or response to therapy and is associated with poor survival (↓ survival).

| Dysplasia | P53 | P16 | P21 | Growth factors | Cell cycle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A = Diagnostic Biomarker | ✓ | |||||

| B = Progression Biomarker | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| C = Predictive Biomarker | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| D = Prognostic Biomarker | ↓ survival | ✓ | ↓ survival | ↓ survival |

Finally, two major questions arise and are still unsolved: (i) why are proposed biomarkers not (yet) really embedded in clinical routine, and (ii) what impairs the identification of more reliable and significant biomarkers?

First of all, two major limitations are the technical and financial aspects. Special molecular biological techniques require fresh frozen samples; DNA-, RNA-extraction, and nucleic acid amplification as well as subsequent hybridization or sequencing are time-consuming and need special facilities which are, again, cost intensive. Additionally, validation of specific methods to detect genetic and epigenetic alterations is still not completed. In conclusion, costs and practicability of these biomarkers are the limiting factors until now [111].

Possible answers to the second question are that more relevant entities like inflammation or epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (EMT), which have yet not been completely considered, should be integrated in the evaluation-process of biomarkers for GERD, BE and EAC.

The potential role of the localized inflammation in disease prediction and prognosis is currently rather underestimated in experimental and clinical investigations. Generally, it has been shown that inflammation influences cancerogenesis by key mediators including reactive oxygen species (ROS), NF-κB, inflammatory cytokines, prostaglandins, and specific microRNAs (miRNAs) [119]. Poehlmann et al. comprehensively reviewed the role of inflammation on genetic and epigenetic changes in BE and EAC focusing on oxidative stress and the NF-κB-pathway [120]. Beside NF-κB and COX-2 (see Table 1), other transmitters of inflammation like chemokines or cytokines should be investigated as possible biomarkers.

Additionally, the process of EMT with its key players Snail, Twist, and ZEB and their repressed target protein E-Cadherin is essentially linked to development, regeneration, inflammation, and cancerogenesis [121]. Several ontogenic pathways (e.g., WNT-, Hedgehog-, or Notch-signaling) are involved in EMT regulation and have also been associated with pathogenesis of BE to EAC as reviewed by Chen et al. [38]. Furthermore, increased expression of SLUG is associated with progression of EAC by consecutive repression of E-Cadherin indicating a role of EMT in EAC. Therefore, subsequent clinical trials have to be set up to elucidate distinct mechanisms of EMT in the pathogenesis of or as specific biomarkers in BE or EAC [122].

5. Approach and Outlook

The probability to find one single specific biomarker providing all diagnostic, predictive, and prognostic significance in GERD, BE, and/or EAC is rather utopian, and a panel of biomarkers maybe will solve this problem [81, 123, 124]. Upcoming new technologies such as RNA and DNA microarrays, epigenetics, and proteomics in association with bioinformatics give hope to find novel and reliable biomarkers in gastrointestinal tumors and especially for prognosis and prediction of BE and EAC [114]. These technologies may provide insights in this rather complex sequence of GERD-BE-EAC; for instance, Kaz et al. [125] stratified BE and EAC by methylation signatures and molecular subclasses using DNA methylation profiling. Interestingly, the authors found an increase of methylation during disease progression—supporting the postulated GERD-BE-EAC sequence and promoting studies of biomarkers based on epigenetic mechanisms which are specific for particular steps in the pathogenetic sequence. Additionally, miRNA profiling by Ko et al. [126] discovered five miRNAs which are significantly expressed in patients with EAC with and without complete remission after therapeutic interventions, whereby the connection of these interesting data to other prognostic/predictive biomarkers in EAC has not been performed. As mentioned by Jankowski and Odze [114], the new technologies are associated with “specific” limitations; RNA and DNA array techniques are retrospective and are frequently lacking phenotype controls. Epigenetic experimental approaches often showed an overlap of methylation pattern between normal and precancerous tissues with no possibility of discrimination between them. Proteomics is time-consuming and not applicable for daily routine work. This seems also true for bioinformatics' techniques.

As depicted in Figure 2, every stage of disease demands intensive morphological, genetic, as well as epigenetic analysis and consequently an exorbitant research effort due to the heterogeneity within the GERD-BE-EAC sequence. However, only consistent generating of data from patients with GERD, GERD with BE, GERD with EAC, or GERD with BE and EAC will allow integrative analysis and research, even if this implies that patients with GERD will be under consecutive, perhaps lifelong surveillance. Therefore, consolidation and evaluation of our intensive but partial not coherent findings regarding the “puzzle” of GERD-BE-EAC represent the first steps to discover the best biomarkers for diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Dr. Otto Dietze for his crucial suggestions regarding paper preparation. They apologize to colleagues whose work could only be cited indirectly. This work was supported by the Wissenschaftlicher Verein der Pathologie Salzburg/Austria.

Abbreviations

- ACIS:

Automated cellular imaging system

- ASS:

Argininosuccinate synthase

- APC:

Adenomatous polyposis coli

- BE:

Barret's esophagus

- COX:

Cyclooxygenase

- DCK:

Deoxycytidine kinase

- DICM:

Digital image cytometry

- EAC:

Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- EGFR:

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ELISA:

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- EMT:

Epithelial-mesenchymal-transition

- FHIT:

Fragile histidine triad protein

- FISH:

Fluorescence in-situ-hybridization

- GERD:

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease

- ICDA:

Image cytometric DNA analysis

- HSP27:

Heat-shock protein 27

- IHC:

Immunohistochemistry

- LOH:

Loss of heterozygosity

- PAPSS2:

3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase 2

- PCR:

Polymerase chain reaction

- qRT:

Quantitative reverse transcriptase

- MDM2:

Mouse double minute 2 homolog

- MLPA:

Multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification

- NF-κB:

Nuclear factor kappa B

- Rb:

Retinoblastoma

- SIRT2:

Sirtuin 2

- SNP:

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- TFF3:

Trefoil factor 3,

- TGF:

Transforming growth factor

- TIMP:

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

- TRIM44:

Tripartite motif-containing 44

- uPA:

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator

- VEGF:

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

- 1.Nebel OT, Fornes MF, Castell DO. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux: incidence and precipitating factors. American Journal of Digestive Diseases. 1976;21(11):953–956. doi: 10.1007/BF01071906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, Appelman H, et al. Prediction of Barrett's esophagus among men. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reid BJ. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 1991;20(4):817–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinstein WM, Ippoliti AF. The diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus: goblets, goblets, goblets. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1996;44(1):91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth CL, Thompson KS. Barrett's esophagus: a review of diagnostic criteria, clinical surveillance practices and new developments. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2012;3(3):232–242. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza RF, Krishnan K, Spechler SJ. Acid, Bile, and CDX: the ABCs of making Barrett’s metaplasia. American Journal of Physiology. 2008;295(2):G211–G218. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90250.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Playford RJ. New British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2006;55(4):442–443. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins GJS, Doak SH, Parry JM, D’Souza FR, Griffiths AP, Baxter JN. Genetic pathways involved in the progression of Barrett’s metaplasia to adenocarcinoma. British Journal of Surgery. 2002;89(7):824–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koppert LB, Wijnhoven BPL, Van Dekken H, Tilanus HW, Dinjens WNM. The molecular biology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2005;92(3):169–190. doi: 10.1002/jso.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid BJ, Li X, Galipeau PC, Vaughan TL. Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma: time for a new synthesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10(2):87–101. doi: 10.1038/nrc2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, Sandler RS. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119(2):333–338. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikkema M, de Jonge PJF, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma and mortality in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;8(3):235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haggitt RC. Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. Human Pathology. 1994;25(10):982–993. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, Inadomi JM, Shaheen NJ. American gastroenterological association technical review on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):e18–e52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaves P, Cardoso P, Mendes De Almeida JC, Pereira AD, Leitão CN, Soares J. Non-goblet cell population of Barrett’s esophagus: an immunohistochemical demonstration of intestinal differentiation. Human Pathology. 1999;30(11):1291–1295. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spechler SJ. Barrett’s esophagus. Seminars in Oncology. 1994;21(4):431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Human Pathology. 1983;14(11):931–966. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldblum JR. Barrett’s esophagus and Barrett’s-related dysplasia. Modern Pathology. 2003;16(4):316–324. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000062996.66432.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr H, Upton MP, Orlando RC, et al. Barrett's esophagus: histology and immunohistology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1232:76–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baretton GB, Aust DE. Barrett's esophagus. An update. Pathologe. 2012;33(1):5–16. doi: 10.1007/s00292-011-1541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fléjou JF, Svrcek M. Barrett’s oesophagus—a pathologist’s view. Histopathology. 2007;50(1):3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curvers WL, Ten Kate FJ, Krishnadath KK, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in barrett’s esophagus: overdiagnosed and underestimated. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(7):1523–1530. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wani S, Puli SR, Shaheen NJ, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus after endoscopic ablative therapy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(2):502–513. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coupland VH, Allum W, Blazeby JM, et al. Incidence and survival of oesophageal and gastric cancer in England between 1998 and 2007, a population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2012;12, article 11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlansky B, Dimarino AJ, Jr., Loren D, et al. A survey of oesophageal cancer: pathology, stage and clinical presentation. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;23(5):587–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(2):461–467. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, et al. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(6):1670–1677. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, et al. Barrett’s esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101(1):12–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid BJ, Haggitt RC, Rubin CE, et al. Observer variation in the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Human Pathology. 1988;19(2):166–178. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomery E, Bronner MP, Goldblum JR, et al. Reproducibility of the diagnosis of dysplasia in Barrett esophagus: a reaffirmation. Human Pathology. 2001;32(4):368–378. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.23510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somerville M, Garside R, Pitt M, Stein K. Surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus: is it worthwhile? European Journal of Cancer. 2008;44(4):588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutman S, Kessler LG. The US Food and Drug Administration perspective on cancer biomarker development. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(7):565–571. doi: 10.1038/nrc1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2001;69(3):89–95. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.113989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennan DJ, Kelly C, Rexhepaj E, Dervan PA, Duffy MJ, Gallagher WM. Contribution of DNA and tissue microarray technology to the identification and validation of biomarkers and personalised medicine in breast cancer. Cancer Genomics and Proteomics. 2007;4(3):121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, et al. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93(14):1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumour Marker prognostic studies (REMARK) British Journal of Cancer. 2005;93(4):387–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzgerald RC. Molecular basis of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2006;55(12):1810–1818. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.089144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen H, Fang Y, Tevebaugh W, et al. Molecular mechanisms of Barrett's esophagus. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2011;56(12):3405–3420. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1885-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clément G, Braunschweig R, Pasquier N, Bosman FT, Benhattar J. Methylation of APC, TIMP3, and TERT: a new predictive marker to distinguish Barrett’s oesophagus patients at risk for malignant transformation. Journal of Pathology. 2006;208(1):100–107. doi: 10.1002/path.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulmann K, Sterian A, Berki A, et al. Inactivation of p16, RUNX3, and HPP1 occurs early in Barrett’s-associated neoplastic progression and predicts progression risk. Oncogene. 2005;24(25):4138–4148. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feber A, Xi L, Pennathur A, et al. MicroRNA prognostic signature for nodal metastases and survival in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2011;91(5):1523–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu Y, Correa AM, Hoque A, et al. Prognostic significance of differentially expressed miRNAs in esophageal cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2011;128(1):132–143. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leidner RS, Ravi L, Leahy P, et al. The microRNAs, MiR-31 and MiR-375, as candidate markers in Barrett's esophageal carcinogenesis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51(5):473–479. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Revilla-Nuin B, Parrilla P, Lozano J, et al. Predictive value of MicroRNAs in the progression of Barrett esophagus to adenocarcinoma in a long-term follow-up study. Annals of Surgery. 2012 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826ddba6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luzna P, Gregar J, Uberall I, et al. Changes of microRNAs-192, 196a and 203 correlate with Barrett's esophagus diagnosis and its progression compared to normal healthy individuals. Diagnostic Pathology. 2011;6, article 114 doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadri SR, Lao-Sirieix P, O’Donovan M, et al. Acceptability and accuracy of a non-endoscopic screening test for Barrett’s oesophagus in primary care: cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2010;341 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4372.c4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lao-Sirieix P, Boussioutas A, Kadri SR, et al. Non-endoscopic screening biomarkers for Barrett’s oesophagus: from microarray analysis to the clinic. Gut. 2009;58(11):1451–1459. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.180281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rygiel AM, Milano F, Ten Kate FJ, et al. Assessment of chromosomal gains as compared to DNA content changes is more useful to detect dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus brush cytology specimens. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2008;47(5):396–404. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barr Fritcher EG, Brankley SM, Kipp BR, et al. A comparison of conventional cytology, DNA ploidy analysis, and fluorescence in situ hybridization for the detection of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Human Pathology. 2008;39(8):1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahlberg PS, Jacobson BA, Dahal G, et al. ERBB2 amplifications in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2004;78(5):1790–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammoud ZT, Dobrolecki L, Kesler KA, et al. Diagnosis of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma by Serum Proteomic Pattern. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2007;84(2):384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murray L, Sedo A, Scott M, et al. TP53 and progression from Barrett’s metaplasia to oesophageal adenocarcinoma in a UK population cohort. Gut. 2006;55(10):1390–1397. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.083295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weston AP, Banerjee SK, Sharma P, Tran TM, Richards R, Cherian R. p53 protein overexpression in low grade dysplasia (LGD) in Barrett’s esophagus: immunohistochemical marker predictive of progression. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(5):1355–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reid BJ, Levine DS, Longton G, Blount PL, Rabinovitch PS. Predictors of progression to cancer in Barrett’s esophagus: baseline histology and flow cytometry identify low- and high-risk patient subsets. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95(7):1669–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rabinovitch PS, Longton G, Blount PL, Levine DS, Reid BJ. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus III: baseline flow cytometric variables. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(11):3071–3083. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reid BJ, Prevo LJ, Galipeau PC, et al. Predictors of progression in Barrett’s esophagus II: baseline 17p (p53) loss of heterozygosity identifies a patient subset at increased risk for neoplastic progression. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(10):2839–2848. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galipeau PC, Li X, Blount PL, et al. NSAIDs modulate CDKN2A, TP53, and DNA content risk for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4(2, article e67) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merlo LMF, Shah NA, Li X, et al. A comprehensive survey of clonal diversity measures in Barrett’s esophagus as biomarkers of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Prevention Research. 2010;3(11):1388–1397. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cronin J, McAdam E, Danikas A, et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and may represent a biomarker of histological progression in Barrett’s Esophagus (BE) American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;106(1):46–56. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sirieix PS, O’Donovan M, Brown J, Save V, Coleman N, Fitzgerald RC. Surface expression of minichromosome maintenance proteins provides a novel method for detecting patients at risk for developing adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(7):2560–2566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lao-Sirieix P, Lovat L, Fitzgerald RC. Cyclin A immunocytology as a risk stratification tool for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(2):659–665. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bani-Hani K, Martin IG, Hardie LJ, et al. Prospective study of cyclin D1 overexpression in Barrett’s esophagus: association with increased risk of adenocarcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(16):1316–1321. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang JS, Guo M, Montgomery EA, et al. DNA promoter hypermethylation of p16 and APC predicts neoplastic progression in barrett’s esophagus. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(9):2153–2160. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin Z, Cheng Y, Gu W, et al. A multicenter, double-blinded validation study of methylation biomarkers for progression prediction in Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Research. 2009;69(10):4112–4115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dahlberg PS, Ferrin LF, Grindle SM, Nelson CM, Hoang CD, Jacobson B. Gene expression profiles in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2004;77(3):1008–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breton J, Gage MC, Hay AW, et al. Proteomic screening of a cell line model of esophageal carcinogenesis identifies cathepsin D and aldo-keto reductase 1C2 and 1B10 dysregulation in barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Proteome Research. 2008;7(5):1953–1962. doi: 10.1021/pr7007835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fang M, Lew E, Klein M, Sebo T, Su Y, Goyal R. DNA abnormalities as marker of risk for progression of Barrett’s esophagus to adenocarcinoma: image cytometric DNA analysis in formalin-fixed tissues. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;99(10):1887–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu C, Zhang X, Huang Q, Klein M, Goyal RK. High-fidelity DNA histograms in neoplastic progression in Barrett’s esophagus. Laboratory Investigation. 2007;87(5):466–472. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vogt N, Schönegg R, Gschossmann JM, Borovicka J. Benefit of baseline cytometry for surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2010;24(5):1144–1150. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0741-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li X, Galipeau PC, Sanchez CA, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism-based genome-wide chromosome copy change, loss of heterozygosity, and aneuploidy in Barrett’s esophagus neoplastic progression. Cancer Prevention Research. 2008;1(6):413–423. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prasad GA, Wang KK, Halling KC, et al. Utility of biomarkers in prediction of response to ablative therapy in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(2):370–379. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dunn JM, MacKenzie GD, Oukrif D, et al. Image cytometry accurately detects DNA ploidy abnormalities and predicts late relapse to high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus following photodynamic therapy. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;102(11):1608–1617. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Langer R, Ott K, Specht K, et al. Protein expression profiling in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients indicates association of heat-shock protein 27 expression and chemotherapy response. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14(24):8279–8287. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schauer M, Janssen KP, Rimkus C, et al. Microarray-based response prediction in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(1):330–337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu X, Gu J, Wu TT, et al. Genetic variations in radiation and chemotherapy drug action pathways predict clinical outcomes in esophageal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(23):3789–3798. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heeren PAM, Kloppenberg FWH, Hollema H, Mulder NH, Nap RE, Plukker JTM. Predictive effect of p53 and p21 alteration on chemotherapy response and survival in locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Anticancer Research. 2004;24(4):2579–2583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakashima S, Natsugoe S, Matsumoto M, et al. Expression of p53 and p21 is useful for the prediction of preoperative chemotherapeutic effects in esophageal carcinoma. Anticancer Research. 2000;20(3 B):1933–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim MK, Cho KJ, Kwon GY, et al. ERCC1 predicting chemoradiation resistance and poor outcome in oesophageal cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2008;44(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peters CJ, Rees JRE, Hardwick RH, et al. A 4-gene signature predicts survival of patients with resected adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, junction, and gastric cardia. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):1995.e15–2004.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prasad GA, Wang KK, Halling KC, et al. Correlation of histology with biomarker status after photodynamic therapy in barrett esophagus. Cancer. 2008;113(3):470–476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lagarde SM, Ver Loren Van Themaat PE, Moerland PD, et al. Analysis of gene expression identifies differentially expressed genes and pathways associated with lymphatic dissemination in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2008;15(12):3459–3470. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0165-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mathé EA, Nguyen GH, Bowman ED, et al. MicroRNA expression in squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus: Associations with survival. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(19):6192–6200. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pasello G, Agata S, Bonaldi L, et al. DNA copy number alterations correlate with survival of esophageal adenocarcinoma patients. Modern Pathology. 2009;22(1):58–65. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Izzo JG, Wu TT, Wu X, et al. Cyclin D1 guanine/adenine 870 polymorphism with altered protein expression is associated with genomic instability and aggressive clinical biology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(6):698–707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang KL, Wu TT, In SC, et al. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in esophageal and esophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas: association with poor outcome. Cancer. 2007;109(4):658–667. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Langer R, Von Rahden BHA, Nahrig J, et al. Prognostic significance of expression patterns of c-erbB-2, p53, p16 INK4A, p27KIP1, cyclin D1 and epidermal growth factor receptor in oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a tissue microarray study. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2006;59(6):631–634. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.034298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Falkenback D, Nilbert M, Öberg S, Johansson J. Prognostic value of cell adhesion in esophageal adenocarcinomas. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2008;21(2):97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brien TP, Odze RD, Sheehan CE, McKenna BJ, Ross JS. Her-2/neu gene amplification by FISH predicts poor survival in Barrett’s esophagus-associated adenocarcinoma. Human Pathology. 2000;31(1):35–39. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ross JS, McKenna BJ. The HER-2/neu oncogene in tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Investigation. 2001;19(5):554–568. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aloia TA, Harpole DH, Jr., Reed CE, et al. Tumor marker expression is predictive of survival in patients with esophageal cancer. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2001;72(3):859–866. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02838-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.D’Errico A, Barozzi C, Fiorentino M, et al. Role and new perspectives of transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α) in adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction. British Journal of Cancer. 2000;82(4):865–870. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Von Rahden BHA, Stein HJ, Feith M, et al. Overexpression of TGF-β1 in esophageal (Barrett’s) adenocarcinoma is associated with advanced stage of disease and poor prognosis. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2006;45(10):786–794. doi: 10.1002/mc.20259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fukuchi M, Miyazaki T, Fukai Y, et al. Plasma level of transforming growth factor β1 measured from the azygos vein predicts prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(8):2738–2741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1096-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kawakami K, Brabender J, Lord RV, et al. Hypermethylated APC DNA in plasma and prognosis of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(22):1805–1811. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.22.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Raouf AA, Evoy DA, Carton E, Mulligan E, Griffin MM, Reynolds JV. Loss of Bcl-2 expression in Barrett’s dysplasia and adenocarcinoma is associated with tumor progression and worse survival but not with response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2003;16(1):17–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2003.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bhandari P, Bateman AC, Mehta RL, et al. Prognostic significance of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in patients with surgically resectable adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. BMC Cancer. 2006;6, article 134 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.France M, Drew PA, Dodd T, Watson DI. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression in esophageal adenocarcinoma as a determinant of clinical outcome following esophagectomy. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2004;17(2):136–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Buskens CJ, Van Rees BP, Sivula A, et al. Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase 2 expression in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(7):1800–1807. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Izzo JG, Malhotra U, Wu TT, et al. Association of activated transcription factor nuclear factor κB with chemoradiation resistance and poor outcome in esophageal carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(5):748–754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gertler R, Doll D, Maak M, Feith M, Rosenberg R. Telomere length and telomerase subunits as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in Barrett carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;112(10):2173–2180. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Saad RS, El-Gohary Y, Memari E, Liu YL, Silverman JF. Endoglin (CD105) and vascular endothelial growth factor as prognostic markers in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Human Pathology. 2005;36(9):955–961. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nekarda H, Schlegel P, Schmitt M, et al. Strong prognostic impact of tumor-associated urokinase-type plasminogen activator in completely resected adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Clinical Cancer Research. 1998;4(7):1755–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Darnton SJ, Hardie LJ, Muc RS, Wild CP, Casson AG. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 (TIMP-3) gene is methylated in the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma: loss of expression correlates with poor prognosis. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;115(3):351–358. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brock MV, Gou M, Akiyama Y, et al. Prognostic importance of promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2003;9(8):2912–2919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Baumann S, Keller G, Pühringer F, et al. The prognostic impact of O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter hypermethylation in esophageal adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;119(2):264–268. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smith CM, Michael MZ, Watson DI, et al. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux on microRNA expression, location and function. BMC Gastroenterology. 2013;13(1, article 4) doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nature Cell Biology. 2008;10(5):593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Russo A, Bronte G, Cabibi D, et al. The molecular changes driving the carcinogenesis in Barrett's esophagus: which came first, the chicken or the egg? Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ong CAJ, Lao-Sirieix P, Fitzgerald RC. Biomarkers in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: predictors of progression and prognosis. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;16(45):5669–5681. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Fang D, Das KM, Cao W, et al. Barrett's esophagus: progression to adenocarcinoma and markers. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1232:210–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huang Q, Hardie LJ. Biomarkers in Barrett’s oesophagus. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2010;38(2):343–347. doi: 10.1042/BST0380343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Jankowski JA, Odze RD. Biomarkers in gastroenterology: between hope and hype comes histopathology. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(5):1093–1096. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Varghese S, Lao-Sirieix P, Fitzgerald RC. Identification and clinical implementation of biomarkers for Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(3):435–441. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Riddell RH, Odze RD. Definition of barrett’s esophagus: time for a rethinkis intestinal metaplasia dead. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(10):2588–2594. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. (7th edition) 2010;7 [Google Scholar]

- 118.Moyes LH, Going JJ. Still waiting for predictive biomarkers in Barrett's oesophagus. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2011;64(9):742–750. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420(6917):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Poehlmann A, Kuester D, Malfertheiner P, et al. Inflammation and Barrett's carcinogenesis. Pathology, Research and Practice. 2012;208(5):269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kiesslich T, Pichler M, Neureiter D. Epigenetic control of epithelial-mesenchymal-transition in human cancer (Review) Molecular and Clinical Oncology. 2013;1:3–11. doi: 10.3892/mco.2012.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Jethwa P, Naqvi M, Hardy RG, et al. Overexpression of Slug is associated with malignant progression of esophageal adenocarcinoma. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(7):1044–1052. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bird-Lieberman EL, Dunn JM, Coleman HG, et al. Population-based study reveals new risk-stratification biomarker panel for Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(4):927–935. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.El Omar EM, Jankowski J. Genetics of Barrett's: the bigger, the better. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2012;107(9):1342–1345. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kaz AM, Wong CJ, Luo Y, et al. DNA methylation profiling in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma reveals unique methylation signatures and molecular subclasses. Epigenetics. 2011;6(12):1403–1412. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.12.18199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ko MA, Zehong G, Virtanen C, et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of esophageal cancer before and after induction chemoradiotherapy. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2012;94(4):1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]