Abstract

T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) proteins regulate transcription by recruiting β-catenin and its associated co-regulators. Whether TCF/LEFs also recruit more factors through independent, direct interactions is not well understood. Here we discover Ring Finger Protein 14 (RNF14) as a new binding partner for all TCF/LEF transcription factors. We show that RNF14 positively regulates Wnt signalling in human cancer cells and in an in vivo zebrafish model by binding to target promoters with TCF and stabilizing β-catenin recruitment. RNF14 depletion experiments demonstrate that it is crucial for colon cancer cell survival. Therefore, we have identified a key interacting factor of TCF/β-catenin complexes to regulate Wnt gene transcription.

Keywords: β-catenin, colon cancer, TCF transcription factors, Wnt

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the most prominent cancer linked to misregulated Wnt signalling. Tumorigenesis is usually initiated by a loss-of-function mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene, which encodes a component of the Destruction Complex for β-catenin degradation [1. Thus, in colon cancer cells, Wnt signalling is constitutively active owing to β-catenin accumulation. Accumulated β-catenin translocates to the nucleus and interacts with T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor (TCF/LEF) regulators to activate a gene transcription programme essential for colorectal adenoma formation. Wnt signalling also has critical roles in embryonic development and adult regeneration.

TCF transcription factors recognize specific DNA sequences referred to as Wnt response elements (WREs) with TLE transcription repressor complexes. These complexes are replaced by the co-activator β-catenin on Wnt stimulation or aberrant accumulation, and extensive studies have searched for β-catenin-interacting factors that counteract repressors to understand constitutive gene activation in cancer [2.

β-catenin and its associated factors are recruited by TCF transcription factors that depend on cooperative interactions with other DNA-binding regulators [3. However, owing to difficulties with purification of active TCF proteins, little is known about whether TCFs directly recruit more co-regulators that synergize with β-catenin for gene regulation. Here, we identify Ring Finger Protein 14 (RNF14) as a TCF-interacting co-regulator of Wnt signalling in cell culture and zebrafish models. We show that RNF14 is required for β-catenin association with WREs and that it has a critical role in developmental gene expression and cancer cell survival.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RNF14 associates with TCF transcription factors

To identify TCF-interacting cofactors, we performed a yeast-two-hybrid screen using the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of human TCF1 as bait (Fig 1A). DBD contains the high mobility group box and the nuclear localization sequence. It is the most highly conserved domain among all TCF/LEFs and the only region capable of independent protein folding [4. One group of complementary DNAs repeatedly isolated from the screen encodes RNF14, a highly conserved protein (supplementary Fig S1A online). RNF14 is broadly expressed in human tissues and acts as a transcriptional co-activator of androgen receptor (AR)-mediated signalling through two functional domains: RING and AR-binding (Fig 1A) [5. RNF14 exhibits E3 ubiquitin ligase activities but its target substrates are unknown except for auto-ubiquitination [6. We identified a sequence in the amino terminus with homology to ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs, supplementary Fig S1A online), suggesting that RNF14 binds ubiquitin.

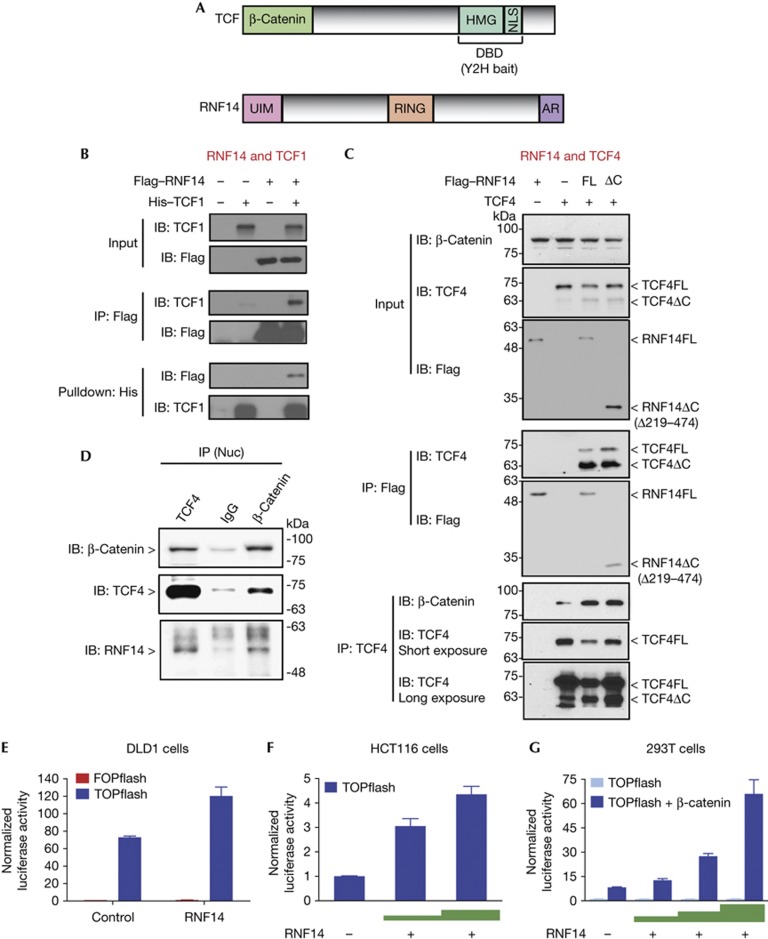

Figure 1.

RNF14 binds TCF and positively regulates Wnt signalling in human cells. (A) Domain structures of TCF including the β-catenin-binding domain and the DNA-binding domain, including the high mobility group box and the nuclear localization sequence, marked as yeast-two-hybrid bait. RNF14 domains include the putative ubiquitin-interacting motif, RING and the androgen receptor-binding region. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation and His-tag pull-down assays using HEK293T cells with overexpressed Flag-RNF14 and His-TCF1. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation experiments using anti-Flag or anti-TCF4 antibodies in HEK293T cells overexpressing TCF4 with either full-length (RNF14FL) or C-terminal deleted (RNF14ΔC) Flag-RNF14. Immunoprecipitated TCF4 was present in two forms: full-length (TCF4FL) and C-terminal truncated (TCF4ΔC, supplementary Fig S1B online). (D) Endogenous RNF14 co-immunoprecipitated with TCF4 and β-catenin in nuclear extracts of HCT116 cells. (E) TOPflash luciferase reporter assays in DLD1 cells overexpressing RNF14. FOPflash reporter was used as a negative control. (F,G) TOPflash assays with increasing amounts of RNF14 transfected in HCT116 cells (F) and HEK293T cells overexpressing β-catenin (G). AR, androgen receptor; DBD, DNA-binding domain; His, histidine; HMG, high mobility group; IB, immunoblotting; IP, immunoprecipitation; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; RNF14, Ring Finger Protein 14; TCF, T-cell factor; UIM, ubiquitin-interacting motif.

To confirm interactions between RNF14 and TCFs, co-immunoprecipitation assays were performed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells. TCF1 was detected by immunoprecipitation of Flag-RNF14 with an anti-Flag antibody, and RNF14 was present in a histidine (His)-tagged TCF1 pull-down with cobalt bead separation (Fig 1B). Co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated that RNF14 also interacts with family members TCF4 (Fig 1C), TCF3 and LEF1 (supplementary Fig S1B,C online). Intriguingly, a 10 kDa smaller, truncated isoform of TCF4 associated more strongly with RNF14 than full-length TCF4 (Fig 1C). Western blot analysis with antibodies against either the carboxy or amino terminus of TCF4 showed that the smaller TCF4 polypeptide lacks the C terminus (supplementary Fig S1D online). In addition, a truncated peptide lacking the C-terminal half of RNF14 (Δ219–474, supplementary Fig S1A online) interacts with TCF4, indicating that it is the N-terminal half of RNF14 that mediates binding. RNF14 overexpression led to increased binding of β-catenin to TCF4 (Fig 1C), suggesting that RNF14 stabilizes β-catenin/TCF interactions. We also performed co-immunoprecipitation in HCT116 colon cancer cells. We confirmed binding between endogenous RNF14, TCF4 and β-catenin (Fig 1D). Thus, RNF14 binds all TCF members in a complex with β-catenin.

RNF14 promotes Wnt signalling in colon cancer cells

To test for a role of RNF14 in Wnt signalling, we used a TOPflash luciferase reporter with multimerized WREs driving luciferase expression. DLD1 colon cancer cells have high levels of active Wnt signalling, as shown by an 80-fold activation of TOPflash over a control reporter with mutant WREs (FOPflash; Fig 1E). RNF14 overexpression enhanced reporter activity by 50% (Fig 1E) with a stronger dose-dependent activity in HCT116 cells, which have a lower baseline of Wnt signalling (Fig 1F). Activation of TOPflash in HEK293T cells by overexpression of β-catenin was greatly enhanced by increasing levels of RNF14 (Fig 1G). A co-transfected β-galactosidase control vector in which transcription is driven by a CMV promoter was not significantly affected by RNF14 (supplementary Fig S1E online), suggesting that it is not a general transcriptional co-activator.

To map the TCF-interacting regions of RNF14, we constructed a series of glutathione S-transferase-tagged deletion mutants (supplementary Fig S2A online) for pull-down experiments with a recombinant, His-tagged DBD of TCF1. Deletion of the RING and AR domains in RNF14 did not alter binding to TCF, whereas an N-terminal deletion reduced the interaction (supplementary Fig S2B online). Thus, RNF14 interacts with TCF, at least in part, through its N-terminal half, which contains the putative UIM. However, because the pull-down was performed with recombinant bacterial protein, this is independent of ubiquitin.

To assess functions of RNF14 domains in the HEK293T transfection assay, we expressed RNF14 deletion mutants lacking either the N terminus or the RING domain. Neither mutant promoted Wnt signalling efficiently (supplementary Fig S2C,D online), but both mutants were unstable as transiently expressed proteins (supplementary Fig S2C,D online). In contrast, deletion of the AR domain enhanced the ability of RNF14 to promote transcription (supplementary Fig S2E online), showing that its Wnt regulatory role does not involve AR signalling and might even be antagonized by AR. Finally, it has been reported that RNF14 can form a homodimer through its C terminus [7. Indeed, deletion of this region (Δ380–474) dramatically reduced its effects on transcription (supplementary Fig S2E online), suggesting that RNF14 dimerization could be important for regulation of Wnt signalling. This region also has a degenerate, but conserved RING domain (supplementary Fig S1A online), which might serve a regulatory role.

RNF14 promotes Wnt signalling in zebrafish in vivo

Zebrafish Rnf14 is 59% similar in amino-acid sequence to human RNF14 (supplementary Fig S1A online). It is expressed both maternally and zygotically during the first 60 h post fertilization (hpf) (supplementary Fig S2F online). To test if Rnf14 promotes Wnt signalling in vivo, we fused the open reading frame of Rnf14 to that of the red fluorescent protein, mCherry, and microinjected rnf14:mCherry messenger RNA (mRNA) into TOPdGFP transgenic fish embryos. The TOPdGFP reporter line expresses destabilized green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of a promoter with multimerized WREs similar to TOPflash. Regions with high levels of active Wnt signalling show GFP fluorescence in living embryos, which is not visible in this line until after 12 hpf [8. Injection of mCherry and β-catenin mRNA was used as negative and positive controls, respectively. At ∼16 hpf in controls, weak endogenous Wnt activity was detected in the midbrain–hindbrain boundary region (Fig 2A). As shown in two examples, Rnf14 mRNA injections dramatically increased Wnt signalling in this area, similar to that observed with β-catenin mRNA (Fig 2A,B). This increase was not owing to morphological changes in the midbrain, as determined by expression of Otx2 (Fig 2A). Importantly, while injected rnf14:mCherry was present throughout the embryo (Fig 2A), Wnt signalling was only enhanced in specific regions such as the midbrain where Wnt activity is normally detected. There is no apparent, aberrant upregulation of Wnt signalling by overexpressed Rnf14 in other regions. These data demonstrate that Rnf14 is a signal amplifier that relies on endogenous Wnt signals for its action and overexpression itself cannot force ectopic activation.

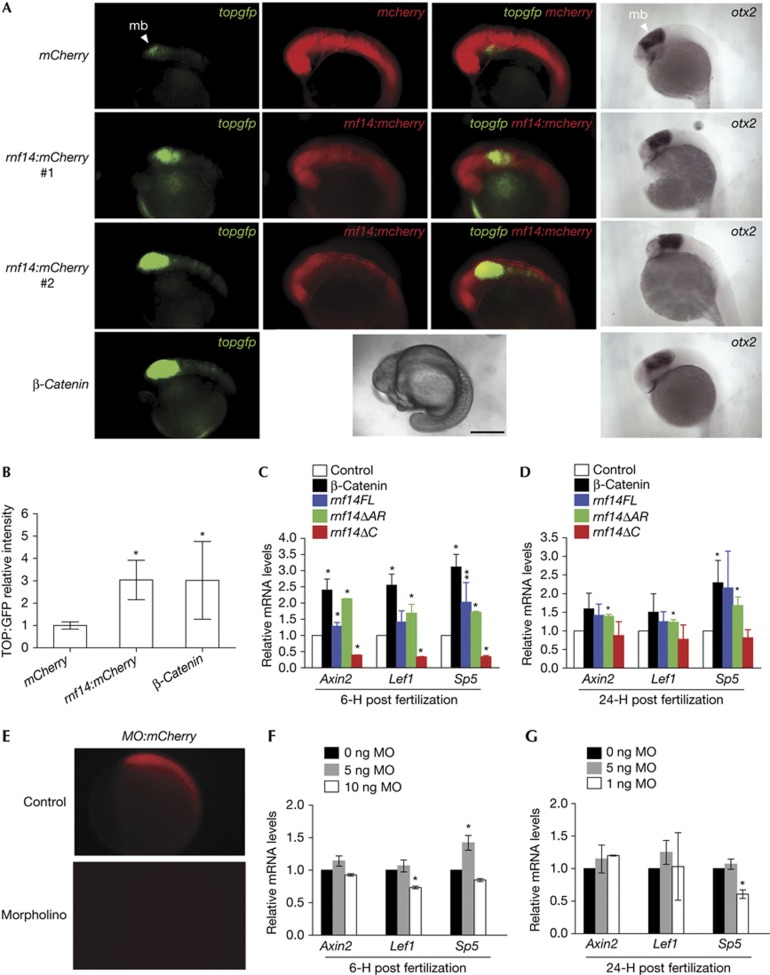

Figure 2.

RNF14 is a co-activator of Wnt signalling in zebrafish. (A) Embryos at ∼16 hpf, lateral views, anterior to the left. TOPdGFP in green reports active Wnt signalling at the midbrain–hindbrain boundary (mb, arrowhead) in living embryos. Microinjection of mCherry mRNA alone and two representative rnf14:mCherry samples are shown in red, while β-catenin mRNA is not labelled. RNA in situ hybridization showed no change in the pattern of otx2 expression in the corresponding injected embryos (right column). Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of green fluorescence in (A) as relative fluorescence intensity: n=20, mCherry; n=22, Rnf14; n=9, β-catenin. (C,D) qRT-PCR analysis showing mRNA levels of Wnt target genes (axin2, lef1 and sp5) normalized to otx2 levels in the injected embryos (control, β-catenin, rnf14FL, rnf14ΔAR and rnf14ΔC) at 6 hpf (C) and 24 hpf (D). (E) Live imaging of 6-hpf embryos co-injected with 2 ng of Rnf14 MO and mCherry containing MO target sequence. (F,G) qRT-PCR analysis of axin2, lef1 and sp5 mRNA levels normalized to otx2 levels in wild-type embryos injected with 0, 5 ng and 10 ng of MO at 6 hpf (F) and 24 hpf (G). *P<0.05, **P=0.05. AR, androgen receptor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; hpf, hours post fertilization; MO, morpholino oligonucleotide; qRT–PCR, quantitative reverse-transcriptase PCR; RNF14, Ring Finger Protein 14.

We next measured changes in Wnt target gene expression in rnf14-injected embryos both during gastrulation (6 hpf) and at 24 hpf when signalling is strong in the midbrain. We performed quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR for three direct Wnt targets: the Wnt signalling component axin2 and transcription factors sp5 and lef1, which are overexpressed in colon cancer [9, [10. Overexpression of full-length Rnf14 increased levels of Wnt target genes at 6 hpf (Fig 2C). The increase was less significant at 24 hpf (Fig 2D), possibly owing to degradation of injected RNA. A Rnf14 deletion mutant lacking the putative AR domain (zebrafish Rnf14 Δ443–459, supplementary Fig S1A online) enhanced Wnt target gene expression while a larger deletion of the C terminus (Rnf14 Δ219–459) could not upregulate these targets. In fact, at 6 hpf, the C-terminal deletion mutant appeared to have dominant-negative effects on transcription (Fig 2C). These results confirm that the AR interaction domain is not required for Rnf14 actions in Wnt signalling but that other more central regions are necessary.

In addition to overexpression, we used morpholino oligonucleotides (MOs) to knockdown endogenous Rnf14. Co-injection of RNA encoding a mCherry reporter with the 25-nucleotide Rnf14-MO target sequence at its translation start site blocked expression starting at 2 ng MO per embryo (Fig 2E). Increasing doses of MO did not affect Axin2 mRNA levels but reduced lef1 and sp5 at 10 ng per embryo (Fig 2F,G). At this dosage and even higher, no overt morphological defects were observed. These data suggest that either knockdown is inefficient, possibly owing to maternally derived mRNA/protein (supplementary Fig S2F online) deposited before MO injection, or that Rnf14 shares redundant functions with other Rnf14-related genes (zebrafish have a second one with 65% similarity). Collectively, the overexpression and knockdown results indicate that Rnf14 is an important modulator of TCF/β-catenin-mediated transcription in vivo.

RNF14 upregulates Wnt targets in colon cancer cells

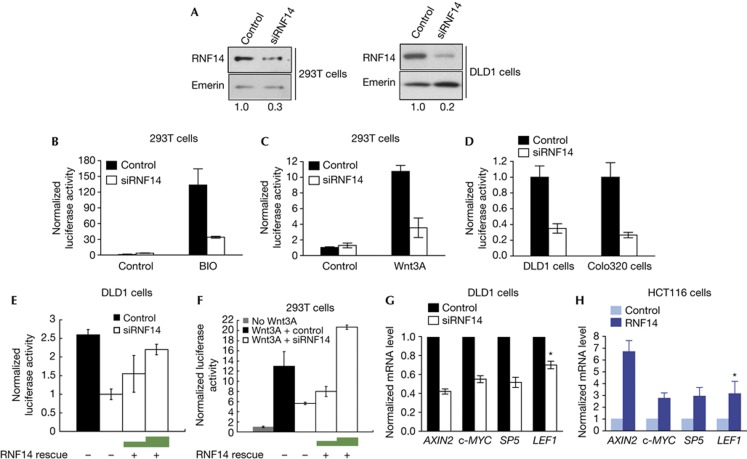

To define requirements for RNF14 in activation of the Wnt pathway in human cells, we used short interfering RNA (siRNA) to knock down expression in HEK293T and DLD1 cells by 70–80% (Fig 3A). We treated HEK293T cells with 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO), a specific inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase 3β, a kinase responsible for β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation. BIO induced Wnt signalling 100-fold and RNF14 depletion reduced this activation by >70% (Fig 3B). In addition, RNF14 knockdown dramatically reduced Wnt3A-induced signalling in HEK293T cells as well as endogenous Wnt activity in colon cancer cells (Fig 3C,D). Overexpression of an siRNA-resistant mutant of RNF14 rescued Wnt activity, confirming siRNA specificity (Fig 3E,F). These results show that RNF14 is required for efficient activation of Wnt signalling in both colon cancer cells with high endogenous Wnt activity and normal cells stimulated by Wnt ligands.

Figure 3.

RNF14 regulates Wnt target gene expression. (A) Relative protein levels of RNF14 in siRNA-treated HEK293T and DLD1 cells normalized to the internal control emerin (B–D). TOPflash assays in BIO- (B) or Wnt3A (C)-treated HEK293T and colon cancer cells (D) with RNF14 depletion (E,F). TOPflash assays in siRNA-treated DLD1 cells (E) and Wnt3A-stimulated HEK293T cells (F) with increasing overexpression of an siRNA-resistant mutant of RNF14 (RNF14 rescue). (G,H) qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt target genes (AXIN2, c-MYC, SP5 and LEF1) normalized to GAPDH for siRNA-treated DLD1 cells (G) and RNF14-overexpressed HCT116 cells (H). *P<0.05. BIO, 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; RNF14, Ring Finger Protein 14; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

We next tested if RNF14 affects expression of endogenous Wnt target genes, including AXIN2, LEF1, SP5 and the oncogene c-MYC. In DLD1 cells, RNF14 depletion reduced the expression of all these genes by 35–60% (Fig 3G). Conversely, RNF14 overexpression increased expression levels 3–6-fold (Fig 3H). Cyclin D1 (CCND1) is another known Wnt target gene that is reported to be upregulated by RNF14 in human glioblastoma cells [11. However, we only detected a slight increase in CCND1 expression following RNF14 depletion in colon cancer cells (supplementary Fig S2G online). This might reflect cell-type-specific roles for TCFs, which in some cases do not regulate CCND1 transcription, especially in the intestine [12.

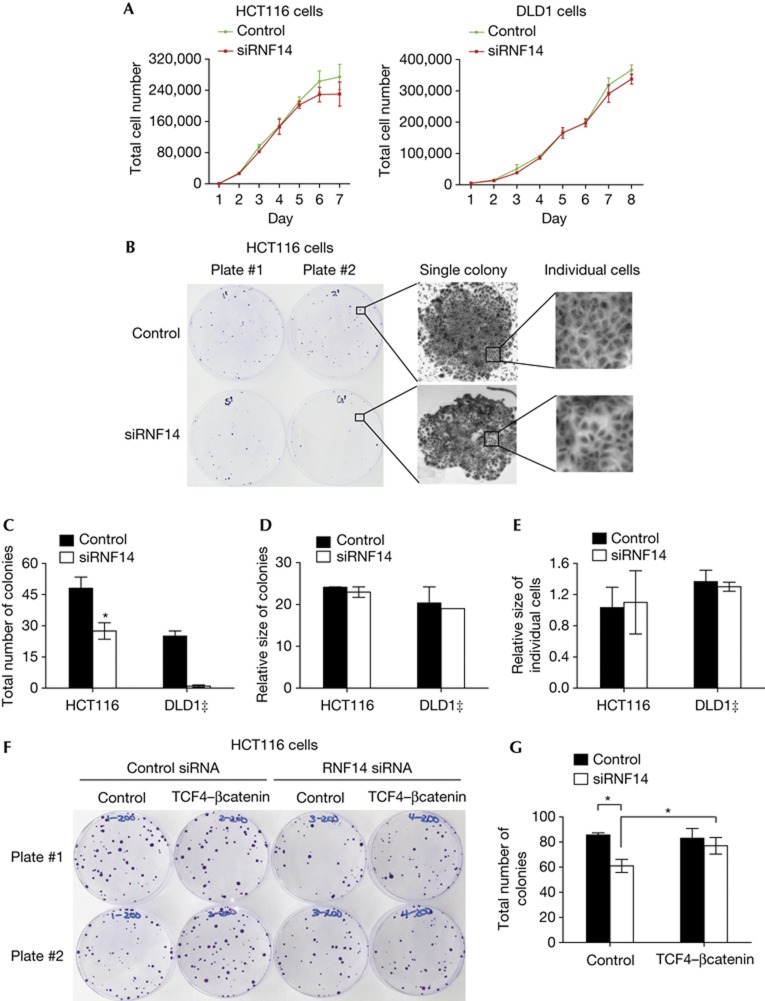

RNF14 is required for colon cancer cell survival

To test if RNF14 has a bona fide functional role in colon cancer cell biology, cell growth assays were performed with depletion of RNF14. Knockdown of RNF14 in HCT116 and DLD1 colon cancer cells caused modest but not statistically significant reduction of cell growth (Fig 4A). To test for survival activities, we plated siRNA-treated cells at low density and followed colony formation from single cells for 10 days. In contrast to the lack of effect on proliferation, RNF14 depletion inhibited colony formation by >40% in HCT116 cells (Fig 4B,C), and the reduction was more pronounced in DLD1 cells (>90%) where more doses of siRNA were supplied during the 10 days (Fig 4C). RNF14 depletion did not affect the average size of colonies or the morphology and size of individual cells (Fig 4B,D). Importantly, colony formation could be rescued by overexpressing a TCF4-β–catenin fusion protein that constitutively activates transcription, implying that the effect of RNF14 depletion is specifically through reduction of TCF/β-catenin-mediated transcription (Fig 4F,G). Therefore, RNF14 is not important for proliferation in vitro but is essential for colon cancer cell survival. From these in vitro studies, we conclude that RNF14 enables TCF/β-catenin to regulate a network of survival-connected Wnt target genes, which might include LEF1 as it is important for survival in other cancers [13.

Figure 4.

RNF14 is essential for colon cancer cell survival. (A) Cell growth assay of siRNA-treated HCT116 and DLD1 cells (see Methods). (B) Colony formation of 100 siRNA-pre-treated HCT116 cells grown on plastic plates for 10 days. Two representative plates were shown for each condition with magnified images of single colonies, which were further magnified to show cell morphology and size. (C) Clonogenic assays in siRNA-pre-treated HCT116 cells, and DLD1 cells with addition of siRNA in the media as indicated with the double dagger symbol (‡). Total number of colonies (more than 50 cells) was counted. n=9 for each condition. (D) Relative size of colonies was measured using ImageJ software in a blinded manner. n=90 for each condition, n=21 for siRNF14-treated DLD1 cells. (E) Relative size of individual cells was determined by ImageJ. n=180. (F) Colony formation of 200 siRNA-pre-treated HCT116 cells for 14 days. Overexpression of TCF4 and β-catenin fusion protein rescued the reduced colony formation by RNF14 depletion. Two representative plates were shown for each condition. (G) The total number of colonies was counted. n=4, *P<0.05. RNF14, Ring Finger Protein 14; siRNA, short interfering RNA; TCF, T-cell factor.

RNF14 stabilizes β-catenin binding to target promoters

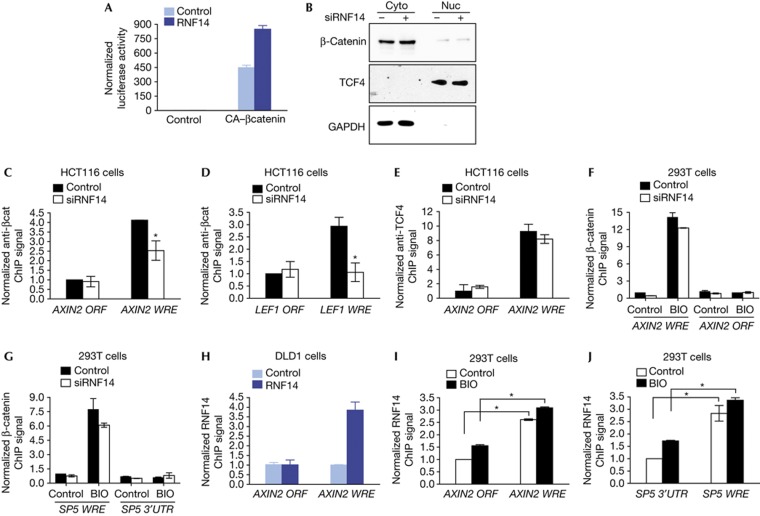

RNF14 has long been known to co-activate transcription with AR; however, the mechanism of its co-activation is still unknown. To define the step at which RNF14 modulates Wnt signalling, we overexpressed a constitutively active, stable form of β-catenin (S33Y) to activate Wnt signalling in HEK293T cells. Co-expression of RNF14 enhanced the activity of S33Y β-catenin (Fig 5A), suggesting that RNF14 can act downstream of β-catenin stabilization. This is further confirmed by the fact that the levels of nuclear β-catenin in DLD1 cells were not affected by RNF14 depletion (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

RNF14 stabilizes β-catenin recruitment at target promoters. (A) TOPflash assays in HEK293T cells transfected with constitutively active (CA)-β-catenin. (B) Levels of nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin in siRNA-treated DLD1 cells with TCF4 and GAPDH as controls. (C–E) ChIP assays in siRNA-treated HCT116 cells for β-catenin enrichment at the WREs of AXIN2 (C) and LEF1 (D), and for binding of TCF4 at the AXIN2 WRE (E). DNA elements within the corresponding ORFs were used as control regions. ChIP signals are normalized to input and values from an IgG ChIP (See Methods). (F,G) ChIP in BIO-treated HEK293T cells with RNF14 depletion for β-catenin enrichment at the WREs of AXIN2 (F) and SP5 (G). An AXIN2 ORF region and the sequence within the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of SP5 are control regions. (H–J) ChIP with an anti-Flag antibody for enrichment of overexpressed Flag-RNF14 at the AXIN2 WRE in DLD1 cells (H) or at the AXIN2 WRE (I) and SP5 WRE (J) in BIO-treated HEK293T cells. *P<0.05. BIO, 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ORFs, open reading frames; RNF14, Ring Finger Protein 14; siRNA, short interfering RNA; TCF, T-cell factor; WREs, Wnt-responsive elements.

In colon cancer cells, β-catenin is recruited by TCFs to WREs in target promoters such as AXIN2, SP5 and LEF1. To test for a role of RNF14 in recruitment, we utilized chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays and observed that in HCT116 cells, RNF14 depletion reduced β-catenin enrichment at AXIN2 and LEF1 WREs by 40%–60% (Fig 5C,D). Importantly, although RNF14 directly binds to TCF, it is not required for TCF association with the target site as knockdown had no effect on TCF occupancy (Fig 5E). RNF14 depletion in BIO-treated HEK293T cells led to only modest decreases in β-catenin binding at the AXIN2 and SP5 promoters (Fig 5F,G). GSK3β inhibitors lead to nuclear accumulation of large amounts of β-catenin protein, which rapidly cycles on and off target promoters [14. It is therefore possible that artificially high levels of BIO-stabilized β-catenin overcome the reduction of RNF14 at target promoters. To test if RNF14 occupies WREs with TCF and β-catenin at target promoters, we performed ChIP assays with overexpressed Flag-tagged RNF14 in colon cancer cells (Fig 5H). Similar to TCFs, RNF14 pre-occupies target sites in the absence of Wnt activity (Fig 5I,J), and occupancy does not change when cells are treated with BIO. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that RNF14 occupies WREs and is required for efficient recruitment of β-catenin at Wnt target promoters.

In addition to enhancing β-catenin occupancy at Wnt target genes, RNF14 might provide complex functions in Wnt-regulated transcription as it is an E3 ligase with a putative UIM in its N terminus. Histone H2B monoubiquitination at Lys123 is required for activation of Wnt target genes [15, and we therefore tested whether RNF14 regulates Wnt signalling through modulating H2B ubiquitination in the ‘Wnt-ON’ colon cancer cells. ChIP assays for ubiquitinated H2B in DLD1 cells revealed abundant H2B ubiquitination within the AXIN2 open reading frame (ORF) and in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of SP5 but no ubiquitination was evident around RNF14-occupied WREs (supplementary Fig S2H online). Therefore, RNF14 and H2B ubiquitination are detected at distinct locations. Furthermore, knockdown of RNF14 did not alter the level of ubiquitinated H2B at the ORF and 3′UTR regions (supplementary Fig S2H online), suggesting that while it is an E3 ligase for ubiquitin, it does not affect H2B ubiquitination.

To activate gene expression, TCFs and β-catenin cooperate to create an enhanceosome that excludes corepressors such as TLEs and HDACs, and includes other tissue-specific factors, histone modifiers and extra auxiliary regulators [2. Our findings reveal RNF14 to be a new cofactor that binds to TCFs and co-occupies Wnt target promoters. On its own, RNF14 overexpression cannot induce Wnt signalling. Therefore, RNF14 is a Wnt signal amplifier and not a signal generator; that is, it relies on bona fide Wnt signals or overexpressed β-catenin for its activities. Here, we provide both in vitro and in vivo evidence that RNF14 specifically promotes Wnt signalling through a mechanism of stabilizing available β-catenin to response elements. We favour a mode of active stabilization of β-catenin occupancy rather than an action that destabilizes the interaction between TCFs and TLE corepressors because the HCT116 cells used in our studies do not have any detectable TLE proteins [16.

We also demonstrate that the functional outcome of RNF14 activity is colon cancer cell survival and Wnt target gene regulation during zebrafish development. These findings highlight RNF14 as a therapeutic target for colon cancer and other diseases linked to Wnt signalling. RNF14 itself is an E3 ubiquitin ligase and it will be essential to identify its target substrates and test for those involved in Wnt signalling. There are other ubiquitination-related co-activators recruited to Wnt target genes, including Trabid that deubiquitinates adenomatous polyposis coli [17, and the E3 ubiquitin ligase TBL1 that interacts with β-catenin [18, and the E3 ubiquitin ligase XIAP targets TLE protein [19. The evolving picture is that TCF and β-catenin recruit a group of factors with several connections to ubiquitin-based activities. It will be important to sort out how these activities and interactions use ubiquitin as a ubiquitin network might lie at the core of Wnt target gene regulation.

METHODS

Zebrafish study. Full-length and deleted rnf14-coding sequences fused to mCherry were subcloned into pCS2+. pCS2-β-catenin was a gift from Dr B Gumbiner (University of Virginia). mRNAs were synthesized using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE SP6 kit (Ambion), and 100 pg per embryo was injected at the 1–2 cell stage into TOPdGFP transgenics or wild-type embryos for in situ hybridization. Whole-mount RNA in situ hybridization was performed as previously described [20. The Otx2 probe was synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase. Embryos were mounted on coverslips and images were taken using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope. An antisense MO (Gene Tools Inc.) was designed targeting the translation start site of Rnf14. The target sequence was fused 5′ to mCherry-coding sequences and subcloned into pCS2+ to generate a reporter RNA to test for MO-knockdown efficiency.

Cell growth and clonogenic assays. HCT116 and DLD1 cells were pre-treated with siRNA for 48 h and grown for 1 week with addition of fresh siRNA-containing media every 2 days. Cells were fixed with 50% trichloroacetic acid and stained with 0.4% (w/v) sulphorhodamine B as described [21. Optical density readings were performed at 450 nm with a DTX800 multimode detector (Beckman Coulter). For clonogenic assays, cells were pre-treated with siRNA for 48 h. One hundred cells were placed on 10-cm plastic dishes and grown for 10 days. More siRNA was added to DLD1 cells during the course of the experiment. For the rescue experiment, an expression vector for a TCF4-β–catenin fusion protein was transiently transfected into siRNA-treated HCT116 cells for 48 h to knockdown RNF14. After 24 h, 200 cells were placed on 10-cm dishes and grown for 2 weeks. 0.2% crystal violet was used to fix and stain the cells. Colonies with more than 50 cells were counted. Individual colonies were photographed under a Nikon ECLIPSE TE2000U microscope.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation. ChIP experiments were performed as described previously [22. Four micrograms of anti-β-catenin (BD Bioscience), anti-TCF4 (Cell Signaling), anti-Flag (Sigma) and anti-ubiquitinated histone H2B Lys123 (MediMabs) were used for the β-catenin, TCF4, Flag-RNF14 and ubiquitinated H2B ChIPs, respectively. Quantitative PCR analysis was used to quantify the ChIP DNA. The ChIP signal was subtracted by values of the background IgG ChIP and then normalized to input. Extra methods are listed in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Masunaga, M. Ho, C. Solomon, T. Zhang and I. Gehring for technical assistance. B.W. and M.L.W. were supported by NIH CA096878, CA108697, P30CA062203 and CIRM RB2-01629; S.P. and T.F.S. were supported by NIH R01DE13828.

Author contributions: M.L.W. and B.W. designed the experiments. T.F.S., S.P. and B.W. designed and performed the zebrafish study. B.W. performed the experiments with assistance from W.Z. and N.P.H., M.L.W. and B.W. wrote the manuscript with editorial input from T.F.S.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bienz M, Clevers H (2000) Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell 103: 311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosimann C, Hausmann G, Basler K (2009) β-catenin hits chromatin: regulation of Wnt target gene activation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 276–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Waterman ML (2012) TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: a007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love JJ, Li X, Case DA, Giese K, Grosschedl R, Wright PE (1995) Structural basis for DNA bending by the architectural transcription factor LEF-1. Nature 376: 791–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HY, Yeh S, Fujimoto N, Chang C (1999) Cloning and characterization of human prostate coactivator ARA54, a novel protein that associates with the androgen receptor. J Biol Chem 274: 8570–8576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K et al. (2001) N-Terminally extended human ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) mediate the ubiquitination of RING-finger proteins, ARA54 and RNF8. Eur J Biochem 268: 2725–2732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto H et al. (2001) A dominant-negative mutant of androgen receptor coregulator ARA54 inhibits androgen receptor-mediated prostate cancer growth. J Biol Chem 277: 4609–4617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsky RI, Sheldahl LC, Moon RT (2002) A transgenic Lef1/β-catenin-dependent reporter is expressed in spatially restricted domains throughout zebrafish development. Dev Biol 241: 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Nakamura Y, Obama K, Furukawa Y (2005) Identification of SP5 as a downstream gene of the β-catenin/Tcf pathway and its enhanced expression in human colon cancer. Int J Oncol 27: 1483–1487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovanes K et al. (2001) β-catenin-sensitive isoforms of lymphoid enhancer factor-1 are selectively expressed in colon cancer. Nat Genet 28: 53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi H et al. (2007) ARA54 is involved in transcriptional regulation of the cyclin D1 gene in human cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 28: 1752–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom OJ et al. (2005) Cyclin D1 is not an immediate target of β-catenin following Apc loss in the intestine. J Biol Chem 280: 28463–28467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding C et al. (2007) Notch1 coopts lymphoid enhancer factor 1 for survival of murine T-cell lymphomas. Blood 110: 2650–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA (2006) The APC tumor suppressor counteracts β-catenin activation and H3K4 methylation at Wnt target genes. Genes Dev 20: 586–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan M et al. (2010) Linking H3K79 trimethylation to Wnt signaling through a novel Dot1-containing complex (DotCom). Genes Dev 24: 574–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce L, Pate KT, Waterman ML (2009) Groucho binds two conserved regions of LEF-1for HDAC-dependent repression. BMC Cancer 9: 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H, Hamada F, Schwarz-Romond T, Bienz M (2008) Trabid, a new positive regulator of Wnt-induced transcription with preference for binding and cleaving K63-linked ubiquitin chains. Genes Dev 22: 528–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang C-Y (2008) TBL1-TBLR1 and β-catenin recruit each other to Wnt target-gene promoter for transcription activation and oncogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 10: 160–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson AJ, Wallace HA, Freeman TJ, Beauchamp RD, Lee LA, Lee E (2012) XIAP monoubiquitylates Groucho/TLE to promote canonical Wnt signaling. Mol Cell 45: 619–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B, Schilling TF, Postlethwait JH (1993) Structure of the zebrafish snail1 gene and its expression in wild-type, spadetail and no tail mutant embryos. Development 119: 1205–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehan P et al. (1990) New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst 82: 1107–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W et al. (2009) Specific loss of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation and HP1γ/cohesin binding at D4Z4 repeats is associated with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD). PLoS Genet 5: e10000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.