Abstract

Globally, health management information systems (HMIS) have been hailed as important tools for health reform (1). However, their implementation has become a major challenge for researchers and practitioners because of the significant proportion of failure of implementation efforts (2; 3). Researchers have attributed this significant failure of HMIS implementation, in part, to the complexity of meeting with and satisfying multiple (poorly understood) logics in the implementation process.

This paper focuses on exploring the multiple logics, including how they may conflict and affect the HMIS implementation process. Particularly, I draw on an institutional logics perspective to analyze empirical findings from an action research project, which involved HMIS implementation in a state government Ministry of Health in (Northern) Nigeria. The analysis highlights the important HMIS institutional logics, where they conflict and how they are resolved.

I argue for an expanded understanding of HMIS implementation that recognizes various institutional logics that participants bring to the implementation process, and how these are inscribed in the decision making process in ways that may be conflicting, and increasing the risk of failure. Furthermore, I propose that the resolution of conflicting logics can be conceptualized as involving deinstitutionalization, changeover resolution or dialectical resolution mechanisms. I conclude by suggesting that HMIS implementation can be improved by implementation strategies that are made based on an understanding of these conflicting logics.

Keywords: Legal and Social issues in Public Health Informatics, developing countries, health management information systems, institutional logics, institutional aspects of information systems, action research, Nigeria, Ministry of Health, change management

Introduction

Health management information systems (HMIS) refer to information systems for health management at district, state, regional and/or national level(s). By implication, they are often government-led and assumedly the foundation for decision-making within health ministries. Globally, they have been hailed as important tools for health reform (1). However, they are yet to live up to expectations because of the significant proportion of failure of implementation efforts (2; 3). Researchers have attributed this significant failure of HMIS implementation, in part, to the complexity of meeting with and satisfying multiple interests and logics in the implementation process (2; 4; 5). Particularly, an emerging body of literature characterizes this situation as that of competing or conflicting institutional logics: a situation where decisions and actions in the implementation process are contested by the different (and sometimes divergent) rationalities or belief systems of the different actors involved (5–7). Accordingly, researchers have indicated the importance of understanding these institutional logics, including how they shape and are embedded in the implementation process, and how they may increase the risk of failure. For example, Chilundo and Aanestad (8) opine that discerning the multiple rationalities that shape implementations is a prerequisite for understanding the implementation process, and a major step towards developing change management strategies to improve it and reduce failures.

This is particularly relevant in the context of developing countries where investments in HMIS implementation draw on already stretched resources. In Nigeria, the empirical context for this paper, the implementation of HMIS is a major concern for the government and its partners, and has been a central component of its public health reform (9). Yet, since its first HMIS implementations in the 1990s, the Nigerian government has continued to struggle with the deployment of information systems to support its public health strategies with limited success (10). However, the recent renewed vigor for HMIS deployments fueled by substantial commitments from international donors and the government’s avowed pursuit of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is creating a situation where an in-depth understanding of HMIS implementation and the institutional logics that shape them are desperately useful if not crucial.

This creates an imperative for hands-on implementation research that can derive lessons that are practically pertinent, contextually relevant, yet theoretically sound such that they can be reused in similar settings (11; 12). Furthermore, the paucity of research in this regard as well as the potential to contribute to the broader sphere of research into institutional logics in information systems implementation add to the strong research motivation for this work.

Empirically, this paper discusses an action research undertaken in Katsina State, Northern Nigeria, with the participation of multiple actors in an HMIS implementation. The implementation provided an opportunity to unravel how conflicting institutional logics may shape an HMIS implementation process. This paper aims to capture and conceptualize these logics and conflicts as well as how they were resolved, and then to suggest implications for practice and research.

The composition of the rest of the paper is as follows: the next section explains the conceptual notion of institutional logics, on which the analytical objectives of the paper lie. Thereafter, the methodology utilized is explained, followed by a description of the context and the findings, interspersed with analytical insights. The paper then presents an analytical summary, after which a discussion on the logics, the conflicts, and the approaches to resolving the conflicts are presented.

Conceptual Framework - Institutional Logics

The theoretical aspects of this paper are founded on an organizational analytic approach based on the concept of institutional logics. Institutional logics refer to belief systems that are carried by a collection of individuals, guiding their actions and giving “meaning to their activities” (13; 20). They “provide the formal and informal rules of action, interaction, and interpretation that guide and constrain decision makers in accomplishing the organization’s tasks” (14). These logics inscribe the “organizing principles” that shape participants’ thinking, influencing both the means and ends of their behavior (15). Thus, institutional actors reproduce logics dominant within their institutional setting (13). Examples of pervasive institutional logics include religious inclinations, marriage preferences, cultures, political ideologies, professional tendencies and ethnically influenced behavior (15; 16). More specifically, and related to our concern, the concept has been applied to understanding information systems implementation in organizations and in a wide variety of domains (6; 17) including the health domain (18–23). These authors describe how institutional logics are embedded within health information systems implementations. Particularly, focus has been on the situation where these logics conflict or compete. For example, Gutierrez and Friedman (23) explain that HMIS project goals and expectations often expose contradictions in the different institutional logics. They argue that HMIS implementation design and planning efforts represent a natural source of contradiction and often involve incompatible perspectives and logics. Similarly, Currie and Guah (20), on analyzing the HMIS in the United Kingdom, describe healthcare as:

“infused with institutional logics emanating from various sectors across the field. Healthcare is politically contentious where societal level logics created by government are embodied in policies and procedures that cascade down from the environment to organizations. Various stakeholders including clinicians, managers, administrators and patients interpret and re-interpret these logics according to the degree to which they affect changes to the perceived or real material resource environment of the institutional actors”.

Currie and Guah (ibid) further argue that “one of the significant challenges facing HMIS implementation is to reconcile competing institutional logics.”

Similarly, Avgerou (21) articulates, in her analysis of an HMIS implementation in Jordan, that the HMIS project had to satisfy two lines of authority with divergent logics - the local bureaucratic structures of the health services, and the USAID (United States Agency for International Development) mission - whose fundamental values and principles about development and organizing were in conflict. She describes:

“These clashed on several issues. Initially, the USAID mission, consistent with its general policy of promoting administrative decentralization, favored a system to address the planning requirements of the 12 governorates (regions) of the country, excluding the central decision makers from the system’s reporting flows. This created friction with the Ministry of Health (MoH), in effect attempting to circumvent technically the current power structures (at the ministry). Second, from the initial conception of the project, the USAID mission wished to focus exclusively on improving the quality of reproductive health services, which is another area of concern and policy for this development agency, (to which the ministry was strongly in disagreement). The aid recipient negotiators of the Ministry of Health shifted the emphasis of the project to primary health care (PHC) instead. Nevertheless, after analysis specifications were drawn and the first prototypes built, a new USAID mission director raised the family planning issue again and asked for the specifications to be changed”

(21).

Avgerou, thus, highlighted two conflicts: one between the logics of decentralization and centralized control; and another involving the scope of intervention between a ‘vertical’ focus on reproductive health (by USAID) and a horizontal broad focus on primary health care (by the ministry).

Recognizing the central role that conflicting logics play in the implementation process, researchers have emphasized the need to understand how to resolve such conflicts. The current understanding is that the resolution of such conflicts usually takes place through a change management process involving deinstitutionalization of one logic and the institutionalization of another (19; 24–27). Deinstitutionalization refers to the process by which institutional logics erode and disappear (25). Sahay et al (19) apply this to describing their work in deinstitutionalizing the logic of paper-based data collection and the institutionalization of a computer-based (electronic processing) logic. However, I argue that conflict resolution in change management processes can also occur without deinstitutionalization or the extermination of one logic. I demonstrate in this paper that the resolution of conflicting logics can occur in an implementation through processes other than deinstitutionalization. I identify two such processes, which I have termed changeover resolution and dialectical resolution. I use changeover resolution to refer to the situation where participants reach a compromise, and then move the project from one dominant logic to another. In other words, changing over dominant logics, yet acknowledging the weakened logic, which becomes recessive but can later be operationalized. On the other hand, I use dialectical resolution to refer to the situation where conflicting logics are resolved through an approach that synthesizes the competing logics into one solution, rather than exterminating one for the other. Here, I adapt the concept of Hegelian dialectics as applied to organizational change i.e. that organizational change occurs through tensions and contradictions, resolved through a synthesis of competing logics (28–33).

In sum, conflicting logics can be resolved through deinstitutionalization, changeover resolution or dialectical resolution. The choice of one depends on the logics involved. Thus, it is important that conflicting logics are identified and understood within projects. However, within HMIS research, there remains a large gap in understanding and identifying institutional logics and the conflicts that may occur between them. This study contributes to filling this gap.

Methodology – The Action Research

The study in this paper focuses on a case of HMIS implementation involving an attempt at introducing and institutionalizing an HMIS software within a Ministry of Health (MoH) with the involvement of many actors. These actors included an international donor funded nongovernmental organization (anonymously referred to as NGO in this paper), a (technical) implementation team, the National and State ministries of health, district health information officers, and health facility workers. The empirical context of this study, as will be described later, is thus a rich one, providing a good setting for studying institutional logics, including how they may shape HMIS implementation.

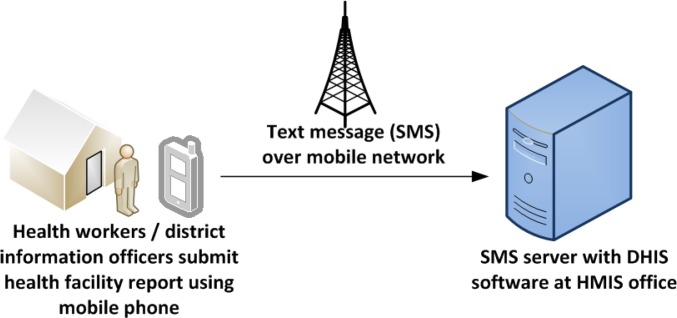

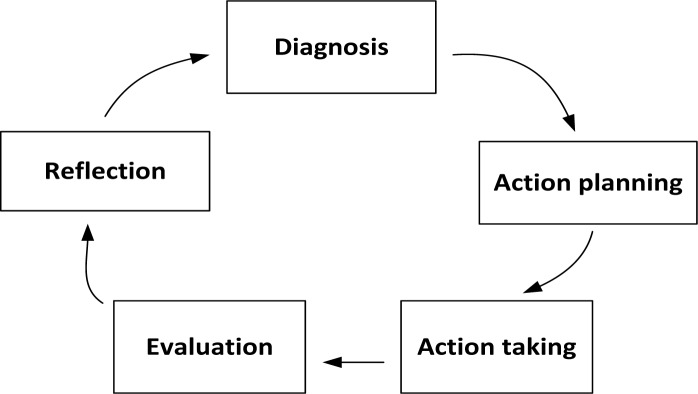

However, studying institutional logics demands an approach that involves being grounded in the context and interacting directly with the logics through active participation with the associated actors. The action research (AR) methodology provides this avenue as it ensures active participation in an organizational change situation while undertaking rigorous theoretically informed research (34; 35). The author was involved as an implementer-researcher within the Health Information Systems Programme (HISP) team, a long-term action research project implementing HMIS in developing countries. AR was applied to this research using the phases described by Susman and Evered (34) - problem diagnosis, action planning, action taking (intervention), evaluation and reflection (see Figure 1 below). In this case though, the phases were not determined beforehand; rather, they evolved and emerged phase after phase, as it was uncertain what the next issues were going to be, or if there would be continued funding for the work. Each phase was decided based on problems and opportunities in the preceding phase, but the implementation and decision-making hinged on the availability of funding, which was intermittent and weak. Thus, planning was piecemeal, rather than following a carefully thought-out ‘grand scheme’. Overall, there were four overlapping implementation1 phases. These phases (also in Table 1 below) include: the establishment of a sentinel system and introducing a computer-based HMIS; strengthening the State HMIS and piloting the mHealth technology; stabilizing/institutionalizing the mHealth technology by hosting internally at the MoH; and finally, migration to Internet-based DHIS2 with remote access through mobile modems.

Figure 1.

Components of an action research phase (34)

Table 1.

Four action research phases carried out in this study.

| Phase 1 - Establishment of sentinels; introducing computer-based HMIS |

| Phase 2 - Strengthening the State HMIS and introducing mobile technology |

| Phase 3 - Stabilizing/institutionalizing the mobile technology by hosting internally at the MoH |

| Phase 4 - Migration to the Internet with remote access through mobile modems |

Data collection

Data collection was ethnographically informed (36; 37) and was done through participant observation (38; 39). The author was involved in all stages of the study, with more involvement in the first three phases. Seven field trips were made between 2008 and 2012, each trip lasting between one and three weeks. Besides the field trips, the implementation work involved numerous phone calls, Skype calls, emails and use of remote login software. Before the study, the author had worked within the MoH in a neighboring state with similar socio-organizational characteristics (language, culture and MoH organizational setup), and had some understanding of the context. Data collection (into field notes) was conducted through activities such as implementation planning meetings with the NGO, discussions with state MoH and district officials; collaborative software customization and configuration activities; field visits to implementation sites; and training and evaluation trips to districts and health facilities.

Data analysis and interpretation

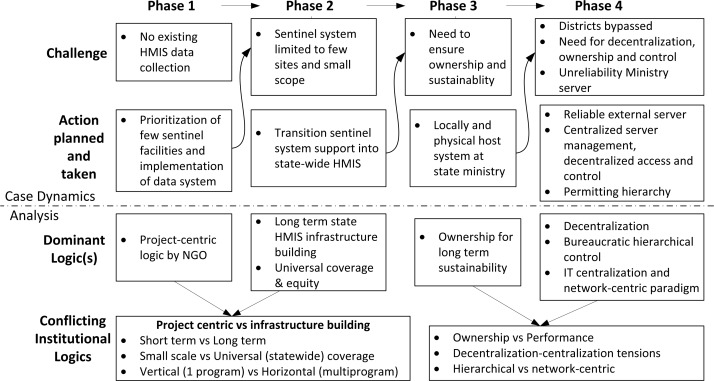

The focus of analysis was on the implementation project, taking it as an organizational field where the actors and their institutional logics play. The collected field notes were analyzed to capture the dominant logics of the different actors in the different phases. Thus data analysis — moving from raw data to interpretation - was based on reiteratively reading and identifying recurring themes from the field data. The data was then transferred to and coded in Nvivo software (40), where case dynamics matrix displays (41) were generated from the institutional logics identified during the reading and rereading process. The notions of institutional logics and its relations were used as a sensitizing device (42), for interpreting meanings and for understanding rationalities behind the dynamics of the implementation process. Nvivo’s support for the framework analysis method (43; 44) was used to generate these displays (see figure 2) and help visualize and identify ‘what was really happening’ in the collected data.

Figure 2.

shows the architecture of the mobile data collection system.

In the next section, I present the action research narrative phase by phase, combined with analytical insights into the dominant logics. Before this, the organizational context is presented.

Case and Findings

Organizational Context

The Nigerian government has long considered the application of ICT as vital to improving the monitoring and evaluation of its public health system via strengthening the system of data collection from health facilities (9). The availability of timely and accurate data is fundamental to improving decision-making within the public health administration, and would help move the country away from its poor health indices. Nigeria, with a population at 162 million (45), is Africa’s most populous country and among ten countries with the world’s worst public health indices: maternal mortality is as high as 1200 per 100,000 live births in some states, i.e. approximately three hundred times more than the average in, for example, Italy (with 3.9 per 100,000 live births). Similarly, infant mortality is among the world’s highest; for example, the last published figures (2003) had infant mortality as high as 100 deaths per 1000 births, compared to 64 in neighboring Ghana and approximately 4 in developed countries such as Norway and Italy in the same year (46).

Since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999, after three decades of military government and systemic neglect of the health care system, there have been concerted efforts at meeting the Millennium Development Goals (including reducing maternal and child mortality). Consequently, public health care reform has been prioritized. These recent reform efforts have been met with increased international vigor and foreign aid to boost the fight against maternal and child mortality, and have involved a focus on strengthening the public health management information system. This paper is centered on a case where foreign aid channeled through an international donor-funded NGO was applied to strengthen the health data collection system in Katsina State, Northern Nigeria.

Katsina State is one of Nigeria’s 36 states, and lies at its Northern border with Niger republic. With a population of approximately 6 million, it is Nigeria’s fourth most populous state – and sixty percent of the population is rural (47). It has a low GDP per capita; over 70% of the population subsists on under 1USD per day and unemployment is over 25% (48). Katsina State is divided geopolitically into 34 local government areas, hereafter referred to as districts. The state has one of the worst indices for maternal and child health in Nigeria, and is considered by the federal government as an educationally less developed and disadvantaged state (49). Successive governments in Katsina State have continued to invest in primary health care (PHC): recent efforts have been aimed at building and rehabilitating PHC facilities, provision of equipment, and the implementation of mobile ambulance services particularly to the state’s difficult-to-reach and rural geographical areas (50). However, management systems such as HMIS have not received much focus, as priority is given to ‘tangible’ goods like drugs, health personnel, and buildings. This is the case in much of Nigeria, where investing in public health management resources is in tension with providing physical deliverables in a sociopolitical system where the masses are desperate for tangible results from the polity.

The current project was initiated by the NGO whose focus was on working with the Katsina State government and districts to improve the availability of maternal and child health services, as well as strengthen the structures and systems that underlie these services. The goal was to establish an information system that could track, monitor, and evaluate progress as well as help strengthen the capacity of state and local government health departments to plan, make decisions and act, based on health data. In addition, the NGO was interested in quickly establishing a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system to collect data that could be used to demonstrate progress to stakeholders and funders. Thus, there was a project-based quick-fix rationality in the foreground, although there was an implicit understanding of the rationale of strengthening the routine system of data collection in the state. Wary of establishing a new parallel information system, and dedicated to adapting to the development ethos of strengthening the state information infrastructure, the project considered the existing (weak) state HMIS as its point of departure.

The HMIS

The HMIS is responsible for data management and statistics within the health ministry at national, state, and district levels. It was established as a “management tool for informed decision-making at all levels” (10), functioning to assess the state of health of the population, identifying major health problems, and monitoring progress towards stated goals. Data flow was designed to be hierarchical, and in a command-and-control structure that reached from health facilities to districts, to state, and then to the federal level.

However, although administrative positions were set up and staff employed, the HMIS remained dysfunctional. HMIS forms were usually unavailable at health facilities, health workers were not trained on how to fill the forms, and filled forms were not submitted. According to the MoH:

“As a result of neglect and underfunding over the years, the National Health Management Information System suffered a lot of setbacks and could not meet the objectives for which it was set up. It has been defective and hence it is not possible to calculate even the simplest indicators”

(10).

The HISP implementation team was invited by an NGO working in Katsina state to help with HMIS reform and implementation based on the existing national HMIS policy and established guidelines.

Phase 1: Establishing sentinels and strengthening the State HMIS

At the beginning of the project, an initial assessment was done which revealed a weak State HMIS system. The HMIS unit was poorly staffed and existing staff were not computer literate. In addition, there were no dedicated computers for HMIS activities and the paper forms/registers recommended by the federal HMIS were not budgeted for. Altogether, there was no culture of information collection, processing, and use.

Much thought was put into how to approach the task of improving the HMIS from the state level through 34 districts to over a thousand health facilities. With limited resources, a prioritization approach was adopted by the NGO to allow focus on a few selected ‘representative’ facilities while beginning the process of strengthening the routine State HMIS team. An improvised sentinel site monitoring system (SSMS) that could swiftly provide some of the initial information required for the monitoring and evaluation of activities was setup.2

The initial setup phase of the sentinel monitoring system lasted five weeks in April/May 2008 and involved planning meetings with the senior management of the MoH, selection of sites, training sessions, and installation of the HMIS software system at the State MoH. Health facilities with the highest level of utilization by the populace (using estimates of maternal and childcare visits) from each of the state’s five zones were chosen to satisfy both geographical and political representation. The officers-in-charge of the sentinel sites and their respective district health officers were trained on the indicators, sentinel system forms, and the data flow for the sentinel site system. After a series of training, monthly data collection by participating health facilities commenced with the forms, which had six indicators focused on immunization. These forms were submitted to the state HMIS office where they were aggregated and analyzed. Analysis was done using the District Health Information Software version 1.4 (DHIS 1.4). The DHIS 1.4 is a Microsoft Access-based software system for the collection, collation, analysis, and presentation of aggregate statistical data designed for the HMIS. It is a generic tool with a flexible configuration system that allows for easy definition of data collection forms. The choice of the DHIS was based on its adoption by the Federal MoH as the de facto standard for public health information management in Nigeria (51). The introduction and configuration of the system was used to train the State HMIS Team on basic HMIS functions as well as DHIS installation and data entry.

Subsequently, follow-up field visits were made to assess the system while providing on-the-job training for health information officers and technical support. Monitoring visits were made to follow-up on the progress that had been made in strengthening the HMIS and establishing the SSMS. During the visits, on-the-job training was facilitated and technical support was given. However, during follow-up visits, based on feedback from the state government that the project should scale up, 31 new sites were added to the initial 14.

Conflicting Logics - Sentinel Project focus vs. Statewide focus

The focus on sentinels introduced minor tensions. It appeared that while HMIS was systemically weak, the priorities of the NGO required a quick solution. The NGO’s logic of implementing a quick-result-seeking system focused on time-bound results was in slight conflict with the state ministry’s focus on the entire routine HMIS. The state ministry’s logic was to strengthen the HMIS statewide and across all aspects of PHC rather than what they considered a quick fix sentinel system focused on one program (immunization).

As one of the state ministry’s health managers argued, “the implementation needs to involve all the districts, health facilities and all aspects of the HMIS, and not just collecting immunization data in a few selected sites.” On the other hand, the NGO had concerns about spreading too thin across the state. Yet, it was generally acknowledged that the sentinel system needed to be gradually adapted into a broader statewide routine data system, so that it could be adapted into the state’s broader agenda of universal and equitable coverage.

A district officer involved at this stage also noted:

“While it is appreciated that the sentinel system is important to monitor NGO interventions, the associated data collection, flow, and analysis should be part of an overall strengthening of the monitoring capacity of the district and state, rather than as a vertical NGO immunization-focused activity”.

With further discussions, the focus began to shift towards the state and district. A more extensive evaluation of the HMIS at all levels and in all districts was thought necessary. Thus, the conflict in this phase was an enabler for the next phase.

Phase 2: Expanding Focus from sentinels to strengthening the routine State HMIS, and introducing mobile technology

Following recommendations from the previous phase, an extensive situational analysis was undertaken in the first quarter of 2009 involving the state, district, and health facility levels. It revealed the very low base from which the HMIS had to be developed. The evaluation showed that there was difficulty with distribution of data collection materials to district facilities across the state Moreover, district HMIS staff had a very poor understanding of the required data collection, collation, and analysis techniques. Furthermore, it was difficult to maintain computer systems within the local governments, with their characteristic poor power supply and sometimes-nonexistent budget for HMIS activities. In addition, transportation between the state and the districts was difficult because of bad roads and a challenging terrain, especially to and from the rural areas. Paper forms were largely unavailable as the state had failed to provide them; reports from the facilities were submitted late to the state/district and data quality was untimely and often incomplete; and communication between district officers and the state HMIS office was poor. Sentinel sites did some reporting but using immunization-focused forms.

With improved mobile network coverage in Katsina (as in the rest of Nigeria), an opportunity to use mobile technology to circumvent some of the mentioned data collection challenges was identified. In addition, the NGO decided to expand the work on the SSMS into the statewide routine HMIS. The routine HMIS became the focus of the intervention.

A large-scale program of training of trainers for the HMIS was designed and implemented. HMIS officers from key data-producing organizations in the state such as the State PHC Board, the State’s main hospital, and the districts were included. The focus was on attaining great effect first at the level and then at lower levels. At the same time, a HMIS Mobile pilot was designed with the goal of exploring the possibilities of using mobile phones for the collection of data from the districts and health facilities. The HISP team developed a simple form-based mobile application for collection and transmission of data into the state level DHIS 1.4 instance. In designing the application, mobile network coverage fluctuations typical of such settings were considered. Data were stored on the phone using a basic Java-based Record Management Store (RMS) functionality, allowing data to be forwarded when mobile network reception returned. It allowed for the retrieval of previously filled reports, adapting well into the context of mobile network signal fluctuations. The application utilized only the basic Java functionalities, such that it could be installed on inexpensive low-end phones. All district officers in the 34 districts were provided with the mobile tool, so that they could submit data for facilities in their areas. Data transmission was via SMS. In addition to the 34 districts, 13 facilities were chosen as pilot sites. The participants were trained on the mobile application and the HMIS forms, and the system was piloted the following month (October 2009). As forms were now budgeted for, advocacy to the state to print forms yielded results. The NGO also printed forms for distribution. With the transition in focus from sentinel to the routine HMIS, the national HMIS forms were introduced for the first time in Katsina. This meant that the mobile training also included training on the content of the form. The contents included all major aspects of PHC, as the state wanted to include items on antenatal care, pregnancy outcome, mortality, family planning, immunization, child nutrition, community outreach - in total, 48 data elements.

On evaluation, positive results were found showing that the implemented mobile solution had a good technical adaptation to the data collection challenges. A simple questionnaire administered to evaluate participant acceptance of the mobile application showed that the application was perceived as useful and appropriate. The district officers and the heads of the pilot facilities were enthusiastic and excited about the system. For the first time, data report submissions were timely. In addition, it obviated the need for long travels (sometimes up to six hours) just to submit a paper form. Overall, a major finding was that the application was well received. As one of the state resource persons said, “let us not call this a pilot because it is bringing very useful results and is now part of the system.” One-hundred percent of the district workers and pilot facilities reported that they preferred this way of reporting as it saved time -they did not need to travel to report - and it was more efficient.

Institutional logics at play - Ownership and Sustainability

With this acceptance and adoption by participating facilities, districts and the state levels there was increased interest in the sustainability and ownership of the system. Of concern was that in these first months the mobile (SMS) server for receiving data was still hosted with HISP outside the state. Considering the logic of local ownership and the rationality of strengthening the state’s routine HMIS infrastructure, it was considered appropriate to move the SMS server to the state HMIS office so that all data were locally hosted. As one of the state HMIS officers said, “We need to be able to run this system here and without your assistance, so that when the project ends we can continue to run it.”

It is important to understand the context; this was a region involved in a disagreement few years before over the safety of polio vaccines, pitting community and Islamic leaders against the WHO, UN, UNICEF, and Federal authorities over fears that polio vaccines were a weapon by Western and international powers (52). The dominant logic from the state was that the system needed to be owned and controlled by the state, and that ownership would lead to sustainability (and perhaps more trust in the system). Ownership here was defined as physically hosting the server (at the MoH). However, the logic from the side of the implementers was on concerns with server stability, maintenance and uptime in the ministry. Yet, the NGO and state agreed on the need for the state to host the SMS server locally. The next phase involved navigating the institutional context of the HMIS and exploring how the system could be institutionalized at the state HMIS.

Phase 3: Attempting Ownership and Institutionalization - Mobile server moved to the MoH

The next line of action was to move the server to the state HMIS office as part of an institutionalization effort. The SMS server was transferred to the state HMIS office and the state HMIS officer trained on its use and management. The move of the server to the state MoH was fraught with a number of issues, including: poor and erratic power supply for the server, short storage of SMS by the mobile network companies, work culture issues, poor server care/maintenance and unauthorized tampering/fiddling. These are explained further.

Power supply is a perennial problem in Katsina State. For the project and the ministry hosting the server, this meant running power generators. However, this introduction brought with it a significant amount of new work for the ministry. They had never been expected to have electricity daily. The ministry was unable to maintain power supply for the SMS server as fuel for the generators was unavailable most of the time because of budgeting/funding and logistical issues. To compound the problem, as was discovered subsequently, SMS’s were not stored by the mobile network for longer than 24–72 hours (depending on the network used). Because of this, not putting the server on for at least 72 hours meant a loss of data. In addition, there were work culture issues; it appeared that coming into the office daily for the state HMIS officer was a challenge as the work culture was lax. The challenges with a poor work culture in the Nigerian civil service are well documented elsewhere in literature (53; 54). It also was observed that the server was poorly maintained. The server was tampered with; for example, the SMS modem driver was uninstalled occasionally and improperly reinstalled, or reconfigured for Internet use. Because of these issues, reporting rates fell by 75%. By the seventh month, data reports received were only 25% of the total, of which half were lost because of inadvertent deletions/disruptions by the State HMIS staff.

The next plan of action was to increase server stability and security by dedicating the server for use for only the mobile project; restricting use by setting and frequently changing passwords. This prevented unauthorized use by outsiders. Improving the power solution was attempted by advocating for increased funding for fuel (for the HMIS office generator), but this did not yield much because budgeting was done in another division (outside the HMIS) and it was difficult to adapt to exigencies. At that time, the budget for the year had not been signed into law. The lack of a budget by the State HMIS precluded other options such as procuring inverters and/or rechargeable dry cell batteries, using solar panel systems or even acquiring another server to run as a backup, a parallel server or a middle tier gateway. In summary, many of the technical options were not possible and the bureaucratic nature of work did not permit much flexibility around the issues.

As the process of salvaging the situation continued, the period of funding for the mobile project by the NGO elapsed, but the team continued with the training of HMIS staff on data analysis, presentation and use. However, on evaluation, despite issues with the server at the ministry, the project was considered by many users in the facilities, districts and the state as a huge success, because it successfully demonstrated that even in the remotest of places, timely and good quality data collection was possible. Consequently, demands increased from other health organizations in the state for the system to be replicated in their organizations. In addition, the districts requested to host their own servers.

Conflicting Logics

Conflicting logics can be observed here. On one hand was the logic for physical “ownership” and physical control of the server as a requirement for sustainability in the long-term. On the other was the implementation team’s technical rationality for objectively improving the data collection system, irrespective of server location or approach. The choice appeared to be between having an externally hosted system (either within the country or outside the country) that performed well, or having an internally hosted (and MoH owned) system that was dysfunctional or, at best, difficult to maintain.

During the evaluation, a pertinent issue arose. It was considered inappropriate (by the districts) for the pilot facilities to submit data directly to the since the dominant decentralization logic for primary health care held that districts needed to manage and utilize data collected within their communities. Furthermore, it was considered important to strengthen the districts, rather than bypass them when health facilities send data. This came up in discussions with the various districts. As one of the district managers said, “the system is not well structured. No district will accept a system where the health facilities report directly to the, bypassing them”. According to one of the state managers, “It is important for districts to receive and analyze all the data sent from facilities in their geopolitical areas, districts should have their own modem and run the server. They should have more capacity than simply sending data from the mobile.” The districts wanted their own servers so that they could also receive data from the health facilities, after which they would submit summaries to the state. However, with the ministry unable to handle the server, the districts were considered even less capable. It was argued that the districts were unable to maintain their desktop systems let alone handle SMS servers.

This can be seen as a conflict between the logic of bureaucratic hierarchy with the need to maintain the existing power and control structure by the districts, and the efficient but network-centric logic of new networked technologies such as mobile technology. Having a central server where all data were submitted from health facilities leading to bypassing the district level appeared to be in tension with the hierarchical structure of the HMIS institution. This network-centric logic versus hierarchical organization logic is an important one. Additionally, related to this was a conflict between the decentralization and centralization logic. This is because a key rationality in public health is decentralization (68–77), such that modes of work that introduce centralized data collection are likely to encounter some tensions. This was exemplified by the districts asking to host or at least control aspects of the system. These related conflicts set the stage for the next phase, involving centralizing the server but decentralizing control and access.

Phase 4: Resolving Conflicts – Decentralizing Access using Mobile Modems and web-based DHIS2

Based on a review of the aforementioned conflicts, the challenge was framed as questions of balance. For example, how could the system be locally owned yet performing efficiently and reliably? How could the centralized collection system permit decentralized control by the districts? How could the network-centric technology support the strongly hierarchical nature of work within the State HMIS?

The solution proposed was to embed control into the information system such that the server was remotely hosted yet controlled by the states and districts through administrative access, restricted based on their roles and area of coverage. Fortunately, there was a new DHIS system (DHIS version 2), which was Web-based and permitted the districts to access and assess activities from the health facilities that fell under their hierarchy. In addition, at this time the telecommunication companies in Nigeria were in a price war over mobile Internet market dominance. This led to a price crash on mobile Internet modems, making them cheap enough for the NGO and the ministry to consider. The thinking was that being able to situate the server on the Internet (for centralized management) would be desirable to the districts, which all wanted distributed access and control of their hierarchy (for decentralized control).

In line with this, a DHIS2 server was configured and installed for Katsina and mobile Internet modems as well as notebook computers were provided for all of the district health offices. Data forms also were migrated from the DHIS 1.4 (MS Access-based system) to the new Web-based system.

The migration to the Web-based DHIS hosted in the cloud retained the advantages of the mobile system. For example, the issues with the difficulty in transportation that the mobile phones were intended to solve were similarly solved, as data transfers could be possible from the districts through the mobile Internet modems. The new DHIS 2 also came with a built-in mobile Web interface as well as a GPRS-based client. This meant that issues with the SMS short storage could be averted. In addition, it helped to spread the coverage of the HMIS to all the districts (as the mobile did) but also relieved the State HMIS of server maintenance work.

In sum, this approached allowed the resolution of a couple of conflicting logics. The centralization-decentralization tension was resolved by allowing decentralized control within a centrally managed information system. However, the network-centric versus hierarchical organization tension has continued to be a challenge. Nevertheless, a step towards resolving or ameliorating it has been to emphasize the supervision of local health facilities by their districts, using the hosted DHIS. For example, Web reports can be reviewed and approved through data review meetings, and reports printed from the DHIS2 application are forming the foundation for continuing the tradition of the HMIS’ hierarchical workflow. In general, the state and the districts were satisfied with being able to have distributed access to data as well as monitoring and supervising health facilities. This was due to the centralized web-based management and the ease of keeping up with modifications and submission from the different districts and facilities.

However, with the dependence on the Internet by the new Web-based HMIS and the unequal distribution of quality mobile Internet access across the districts, issues of universal coverage and equity were again becoming a concern, especially from the districts with poorer access. Universal coverage and equity are foundational logics in public health, and a key aspect of what defines success within the HMIS context. These emerging conflicts will (again) need to be navigated as the project continues to evolve. Universal and equitable coverage of the state was a motivation for the transition from the sentinel system to the HMIS in earlier phases of the project. Therefore, it appears that it has manifested in another form in this later stage.

Analytical Summary of Findings

The preceding description with analytical insights has followed the evolution of an HMIS implementation within a challenging context, highlighting the interplay between the technological solution, the institutional arrangements and stakeholder perspectives. It has exposed multiple institutional logics including where they conflicted, how they shaped the implementation process, and how they were resolved were possible.

Figure 3 below is a case dynamics matrix (41) showing the challenges and the actions planned and taken in each phase. Included are highlights of the dominant institutional logics and conflicts in each phase of the project.

Figure 3.

Case dynamics matrix showing the dynamics of the case

Discussion

This case has three major analytical findings: Firstly, it revealed the institutional logics that played a role in the HMIS implementation process; secondly, it highlighted how the evolution of the implementation through the action research is fueled by conflicting logics and the drive to resolve them; lastly, it highlighted the approaches for resolving these conflicts. I discuss these three aspects briefly.

Institutional logics in the HMIS

This study has highlighted institutional logics that are some of the most fundamental logics in HMIS implementation. This claim is substantiated by the fact that previous researchers have highlighted the role and importance of these logics in shaping other cases of HMIS implementation, especially in the context of developing countries. For example, the short term project-centric quick win logic in NGO internationally funded projects has been exemplified and discussed by many researchers (21; 55; 56). Avgerou, for instance, highlights this project-based rationality when she discusses a similar case of international donor-led HMIS implementation in the Jordanian public health sector (21). Other researchers have followed this through from the perspective of sustainability and describe how HMIS projects are driven by the fundamental logic of sustainability (57–62). A dominant logic linked to this is that sustainability can be achieved through local ownership of implemented HMIS systems (63–66). Along the same lines, HMIS implementers and researchers have emphasized the logic of local control extensively discussed as decentralization (56; 67–77). Furthermore, the institutional logic of universal coverage, which we saw as translating to the need for state-wide coverage of the HMIS, is one that has been described as “the single most powerful concept that public health has to offer” (78) and one that requires HMIS to scale (79). Additionally, other HMIS cases have described the institutional logic of rigid bureaucracy and maintaining hierarchical power structures (19). Less reported though has been the logic of network-centric organization (80–83) where network technologies such as Web and mobile-based HMIS disrupt existing power structures because they allow more communication. Overall, using the case, the author exemplifies and identifies what can be considered as foundational logics of which HMIS implementation planners and designers need to be concerned and aware.

Conflicting Logics

Perhaps, even more important to recognize is that fundamentally, these logics sometimes conflict, thereby increasing the risk of implementation failure (2). However, conflicting logics can be a major enabler and driver for organizational change processes (6). The case described here suggests that the challenges and reactions in each phase were motivated by the need to resolve conflicting logics that emerged from the previous phase. In this way, conflicting logics can be seen as enablers and drivers for an implementation’s change process. Identifying the conflicts that arose within the implementation process was a key problem-solving step, as well as an important change management process for the implementation. Thus, I agree with researchers (17; 19; 84) who contend that identifying these logics is a major step towards improving implementations. This case provides examples of conflicting logics that implementers can watch for in HMIS implementation (see Figure 3 above and Table 2 below). These conflicting logics appear consistent with prior research. For example, some researchers (85, 86) have similarly emphasized conflicting institutional logics arising between a project’s short term quick win focus and a long-term infrastructure-building perspective, similar to the issue here between the NGO’s initial quick win focus and the state’s long range focus. The conflict between focusing small scale and going large scale is crystallized in the struggle between running pilot projects that then struggle to scale in line with the goals for universal coverage (3; 87). This was also the situation in the Jordanian HMIS case (21). The third conflict — between focusing on small/vertical scope (one disease) or focusing broadly on the larger primary health system (broad horizontal scope) is also supported in HMIS literature (88–90). The conflict between ownership and performance is one that has been a bane of many HMIS projects in developing countries, such that the goal of local ownership often ruins the objective of performance where the capacity for maintaining the performance is unavailable (91; 92). The other issues from this case on balancing decentralization-centralization (68; 70; 77; 93–96) and the conflict between hierarchical vs. network-centric logics (81; 82; 97) are also important reported HMIS concerns.

Table 2.

Conflicting institutional logics, examples from the case and resolution strategy.

| Conflicting institutional logics | Example from case | Resolution strategy | Type of resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short term vs. long term | Quick win sentinel system vs. long term HMIS building | Transitioned from short term thinking to long term | Transitional resolution |

| Small scale vs. Universal scale | Sentinel system in only 14 facilities vs. statewide HMIS in all districts | Transitioned from sentinel system to statewide HMIS | Transitional resolution |

| Vertical (program) vs. horizontal (whole systems) | Immunization-focused sentinel system vs. HMIS focused on broad scope of primary health care | Transitioned from vertical immunization system to broad HMIS | Transitional resolution |

| Ownership vs. Performance | Locally ‘owned’ and (state) hosted server performed poorly, while externally hosted server performed well | Found a balance: A locally controlled Internet server satisfied both local ownership and gave good performance | Dialectical resolution |

| Hierarchical vs. network-centric | Submissions from facilities over the mobile network bypassed the districts disrupting existing hierarchical structure | Found a balance: Districts have access to data from facilities and have sufficient power to assess/approve data for facilities under them | Dialectical resolution |

| Decentralization-centralization | Centralized state server vs. districts wanting to host their own server and achieve control of health facilities | A balance: Centralized Internet-based server management actually helped decentralize access and control | Dialectical resolution |

Table 2 below is a succinct summary of these conflicting logics and how they were resolved. The resolution strategies are discussed below.

Resolving Conflicting Logics

The third set of analytical findings relate to how conflicting logics were resolved. Understanding the resolution of these conflicts has been a major concern for practitioners and researchers (5; 6; 19; 98; 99) Largely, the existing literature points to deinstitutionalization. However, this paper suggests that there are alternative strategies. Deinstitutionalization refers to the process by which institutional logics erode and disappear (25). Particularly, Sahay et al (19) have used this to explain how the logic of paper use in the Tajikistan HMIS was deinstitutionalized (or removed) through the introduction of computer-based HMIS. In our case, the changeover from the short-term sentinel focus to a broad, ‘universal coverage’-seeking approach involved changing from one dominant logic to another. Rather than describe this as the total removal (deinstitutionalization) of an institutional logic, it appears more appropriate to see it simply as conflict resolution through switching the project from one logic to the other without necessarily destroying the other logic, which, perhaps, continues to exist elsewhere. I have termed this approach to resolving conflicting logics as changeover-resolution. It can be understood better when seen in contrast to another approach I have termed dialectical resolution, which often occurs when resolution occurs not through changeover but by balancing two competing interests. For example, in this case, by centralizing the mobile server management on the Internet (phase 4), the implementation decentralized access to the server, balancing and creatively combining both centralization and decentralization. The conflict was not resolved by changing from one logic to another, but rather by synthesizing both sides and finding a combinational balance. Thus, dialectical resolution involves mindfully balancing between competing logics rather than taking them as if in a black-white dichotomy. A more extensive discussion of dialectics can be gleaned from the literature (28; 30; 33; 100).

An inference for practice is that implementers need to look out for conflicts and build bridges between them. These bridges could take different forms: either a bridge that permits a changeover-resolution, or a bridge that permits the marriage between two sides (dialectical resolution). The third strategy - deinstitutionalization - appears to be an approach to building a bridge to allow crossover, and then burning one side of the bridge in attempt to exterminate one logic. In sum, this paper proposes an understanding of the resolution of conflicting institutional logics as consisting of three possible strategies - deinstitutionalization, changeover resolution (logical switching/transition) and dialectical resolution (see summary in table 3 below).

Table 3.

Three strategies for handling conflicting institutional logics

| Deinstitutionalization (as in Sahay et al. (19)) | Changeover resolution (as proposed in this paper) | Dialectical resolution (as described in this paper) |

|---|---|---|

| When one logic needs to be obliterated, to give way to a new paradigm | When actors need to focus on one logic, and compromise the other (not necessarily obliterate it) | The conflicting logics need to be both adopted and combined within the implementation |

Further Implications

In this section, I summarize the implications of the analysis for HMIS practice and research and outline the contributions made to institutional logics research.

Looking back at the approach and setting of this study, like other context-sensitive studies, generalization from this single case has the risk of being weak or limited. However, as I have shown in the preceding sections with numerous references to previous research, this case is typical of HMIS implementation in developing countries. The findings and the interpretations I have made from this case clearly sit well within the framework of previous studies and the body of literature, and there is substantial support for taking these broadly, in a way reusable and applicable to similar situations. Building on this, the analysis has implications not just for HMIS implementation in Nigeria but also similar contexts where conflicting institutional logics play a role.

Many HMIS implementations, by virtue of involving multiple actors and interests, will involve an interaction of many institutional logics with some conflicting in the implementation process. From a practical perspective, implementers need to take these logics more seriously. The analysis of this case sensitizes us to the role that conflicting institutional logics play by increasing the risk of project failure, when not resolved. This is particularly important as success or failure often is constructed by the actors and through the logic with which they perceive the implementation process. Therefore, it appears that for implementations to be successful, implementers may need to negotiate and navigate the different logics of the participating actors. In cases where these negotiations were not possible e.g. in the cases described by Silva and Hirschheim (101), Avgerou (21) and Kaduruwane (92), the implementation was unsuccessful. In developing countries, especially with limited resources, if we can improve in the negotiation of the conflicting logics that arise in implementations, we may significantly improve the implementation of HMIS, and improve health systems and foster socioeconomic development down the line.

In relation to the foregoing, another implication is that HMIS, and by extension, information system design and development within the context of conflicting logics, may need to be done in ways that support the transition between logics or in ways that support the coexistence of multiple logics. In the case discussed here, the ability to navigate the different logics was partly because of the flexibility of the information system and how it could differentially support multiple, and even conflicting, logics.

In conclusion, through the application of the notion of institutional logics and its related concepts, this paper has extended our understanding of HMIS implementation. The paper has typified the institutional logics involved in HMIS implementation, including where they may conflict. In addition, it has expanded our understanding of mechanisms for resolving implementation conflicts – by proposing the concepts of changeover resolution and dialectical resolution, as an addition to the existing concept of deinstitutionalization. I reckon that these are pertinent contributions, and it may be beneficial for researchers to extend these concepts further and broaden our understanding in other contexts.

While HMIS implementation generally is seen as a difficult and complex process, I believe that understanding the dominant and conflicting logics at play can provide implementers with deep insight into aspects to examine when performing needs and situational analyses, as well as when developing implementation and change management strategies. This paper has already highlighted some of the logics that should be considered – e.g. the need for decentralization, hierarchy and centralization, long-term sustainability, ownership, universal coverage (and scale up) and short-term project focus - and the conflicts that may arise between them. Preempting and planning for these may enhance the prospects of HMIS implementation success, especially in developing country MoH contexts.

Footnotes

Implementation in this paper refers to the processes of action planning, action taking (intervention) and evaluation as described in action research (34, 35)

A sentinel site is a health facility that can provide information considered to be representative of the population’s health indices - serving as a proxy for assessing the health system.

References

- 1.AbouZahr C, Boerma T. Health information systems: the foundations of public health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83(8):578–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heeks R, Mundy D, Salazar A. Understanding success and failure of health care information systems. In: Armoni Adi., editor. Healthcare Information Systems: Challenges of the New Millennium. Idea Group Publishing; 2000. pp. 96–128. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heeks R. Health information systems: Failure, success and improvisation. International journal of medical informatics. 2006;75(2):125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahay S, Monteiro E, Aanestad M. Configurable politics and asymmetric integration: Health e-infrastructures in India. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2009;10(5):399–414. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reay T, Hinings CR. Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies. 2009;30(6):629–652. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornton PH, Ocasio W. Institutional logics. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Sage: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pache AC, Santos F. When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. The Academy of Management Review (AMR) 2010;35(3):455–476. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilundo B, Aanestad M. Negotiating multiple rationalities in the process of integrating the information systems of disease specific health programmes. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries. 2005;(20):2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Ministry of Health. The National Strategic Health Development Plan Framework 2010–2015. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health Planning and Research National Health Management Information System Policy, Programme and Strategic Plan of Action. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avgerou C. The significance of context in information systems and organizational change. Information Systems Journal. 2008;11(1):43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoogah DB. African business research: A review of studies published in the Journal of African Business and a framework for enhancing future studies. Journal of African Business. 2008;9(1):219–255. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott WR, Ruef M, Mendel PJ, Caronna CA. Institutional change and healthcare organizations: From professional dominance to managed care. University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ocasio W. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal. 1998;18(S1):187–206. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedland R, Alford RR. Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In: Powell Walter W, DiMaggio Paul., editors. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis. University of Chicago Press; 1991. pp. 232–266. [Google Scholar]

- 16.North DC. Institutions. The journal of economic perspectives. 1991;5(1):97–112. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes N, Rajão R. Competing institutional logics and sustainable development: the case of geographic information systems in Brazil’s Amazon region. Information Technology for Development. 2011;17(1):4–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeow A, Faraj S. Microprocesses of healthcare technology implementation under competing institutional logics. Proceedings of 2011 International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS2011); Dec 4–7, 2011; Shanghai, China. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahay S, Sæbø JI, Mekonnen SM, Gizaw AA. Interplay of Institutional Logics and Implications for Deinstitutionalization: Case Study of HMIS Implementation in Tajikistan. Information Technologies \& International Development. 2010;6(3):19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Currie WL, Guah MW. Conflicting institutional logics: a national programme for IT in the organisational field of healthcare. Journal of Information Technology. 2007;22(3):235–247. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avgerou C. IT as an institutional actor in developing countries. In: Krishna S, Madon S, editors. The digital challenge: information technology in the development context. Ashgate, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing; 2004. pp. 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koç O, Vurgun L. Managing the Rivalry of Antithetic Institutional Logics: A Qualitative Study in the Scope of Turkish Healthcare Field. 2012;8:157–174. Ekonomik ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, Bahar 2012, Cilt:8, Yıl:8, Sayı:1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutierrez O, Friedman DH. Managing project expectations in human services information systems implementations: The case of homeless management information systems. International Journal of Project Management. 2005;23(7):513–523. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver C. The antecedents of deinstitutionalization. Organization studies. 1992;13(4):563–588. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dacin MT, Dacin PA, Greenwood R, Oliver C, Sahlin K, Suddaby R. Traditions as institutionalized practice: Implications for deinstitutionalization. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. 2008;327:352. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott WR. Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. Great minds in management: The process of theory development. 2005:460–484. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dacin MT, Goodstein J, Scott WR. Institutional theory and institutional change: Introduction to the special research forum. The Academy of Management Journal. 2002;45(1):43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seo MG, Creed WED. Institutional contradictions, praxis, and institutional change: A dialectical perspective. Academy of Management Review. 2002:222–247. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivos EM. Tensions, contradictions, and resistance: An activist’s reflection of the struggles of Latino parents in the public school system. The High School Journal. 2004;87(4):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van de Ven AH, Poole MS. Explaining development and change in organizations. Academy of management review. 1995:510–540. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farjoun M. The dialectics of institutional development in emerging and turbulent fields: The history of pricing conventions in the on-line database industry. Academy of Management Journal. 2002:848–874. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mumby DK. Theorizing resistance in organization studies. A dialectical approach. Management Communication Quarterly. 2005;19(1):19–44. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nordheim S. Implementing an Enterprise System: A dialectic perspective. Aalborg University, The Faculty of Engineering and Science, Information Systems; 2009. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Susman GI, Evered RD. An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative science quarterly. 1978:582–603. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay J, Marshall P. The dual imperatives of action research. Information Technology & People. 2001;14(1):46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herman E, Bentley ME. Manuals for ethnographic data collection: experience and issues. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;35(11):1369–1378. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90040-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartmann T. Evolutionary Software Development to Support Ethnographic Action Research. Computing in Civil Engineering: Proceedings of the 2011 ASCE International Workshop on Computing in Civil Engineering; June 19–22, 2011; Miami, Florida. 2011. p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baskerville RL. Investigating information systems with action research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 1999;2(3):4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jorgensen DL. Participant observation: A methodology for human studies. Sage Publications, Incorporated; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bazeley P. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Sage Publications Limited; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klein HK, Myers MD. A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS quarterly. 1999;23(1):67–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. 2002:305–329. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woodfield K, O’Connor W. “Framework”, Computer-assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software and its Role in Increasing Quality and Transparency in the Analysis of Qualitative Data. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The World Bank World Development Indicators - Nigeria [Internet] 2012. [cited 2012 Nov] Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/country/nigeria.

- 46.World Health Organization Global Health Observatory Data Repository [Internet] 2012. [cited 2012 Nov 28] Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/

- 47.National Population Commission . Population Distribution By Sex, State, LGA & Senatorial District. 2006. Census. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Bureau of Statistics. Katsina State Information [Internet] 2012. Available from: http://www.webcitation.org/6CVZt8rpT.

- 49.Department of Economic Planning . Katsina State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (SEEDS); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katsina State Government 2012. Development Focus - Health [Internet] Available from: http://www.webcitation.org/6CVTCjga7.

- 51.Asangansi I, Shaguy J. Complex dynamics in the socio-technical infrastructure: The case of the Nigerian health management information system. Proceedings of the IFIP9.4 10th International Conference on Social Implications of Computers in Developing Countries; Dubai. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Obadare E. A crisis of trust: history, politics, religion and the polio controversy in Northern Nigeria. Patterns of Prejudice. 2005;39(3):265–284. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olowu B. Redesigning African civil service reforms. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 1999;37(01):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olowu D. Bureaucratic morality in Africa. International Political Science Review. 1988;9(3):215–229. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfeiffer J. International NGOs and primary health care in Mozambique: the need for a new model of collaboration. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(4):725–738. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimaro HC, Nhampossa JL. The challenges of sustainability of health information systems in developing countries: comparative case studies of Mozambique and Tanzania. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries. 2004;1(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimaro HC, Nhampossa JL. Analyzing the problem of unsustainable health information systems in less-developed economies: Case studies from Tanzania and Mozambique. Information Technology for Development. 2005;11(3):273–298. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avgerou C. Discourses on ICT and Development. Information Technologies and International Development. 2010;6(3):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coiera E, Hovenga E. Building a sustainable health system. IMIA Yearbook of Medical Informatics. 2007;2(1):11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sander J, Bell P, Rice S. MIS sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa: Three case studies from The Gambia. International. Journal of Education and Development using ICT. 2005;1(3) others. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis JL. Making public health programs last: conceptualizing sustainability. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2004;27(2):121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abu Mourad T, Radi S, Shashaa S, Lionis C, Philalithis A. The Health Management Information System in Primary Health Care: The Palestinian Model. Proceedings of the Saudi Association for Health Informatics (SAHI) 2008 e-Health Conference; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimaro HC. Strategies for developing human resource capacity to support sustainability of ICT based health information systems: a case study from Tanzania. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries. 2006;26(2):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith N, Littlejohns LB, Thompson D. Shaking out the cobwebs: insights into community capacity and its relation to health outcomes. Community Development Journal. 2001;36(1):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dada D. The failure of egovernment in developing countries: A Literature review. Electronic Journal of Information Systsems In Developing Countries. 2006;26(7):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hansen H, Tarp F. Aid effectiveness disputed. Journal of International development. 2000;12(3):375–398. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aqil A, Lippeveld T, Hozumi D. PRISM framework: a paradigm shift for designing, strengthening and evaluating routine health information systems. Health Policy and Planning. 2009;24(3):217–228. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rockart JF, Leventer JS. Centralization vs decentralization of information systems: a critical survey of current literature. 1976;(CISR-23) [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhattacharya J, Ghosh R, Nanda A. Micro Health Centre (uHC) - A cloud-enabled healthcare infrastructure. Journal of Health Informatics in Developing Countries. 2012;6(2) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Heeks R. Centralised vs decentralised management of public information systems: a core-periphery solution. Information Systems for Public Sector Management Working Paper Series by Institute for Development Policy and Management; University of Manchester, UK. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sandiford P, Annett H, Cibulskis R. What can information systems do for primary health care? An international perspective. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;34(10):1077–1087. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90281-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maluka SO, Hurtig AK, Sebastián MS, Shayo E, Byskov J, Kamuzora P. Decentralization and health care prioritization process in Tanzania: From national rhetoric to local reality. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2011;26(2):102–120. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Litvack JI, Ahmad J, Bird RM. Rethinking decentralization in developing countries. World Bank, Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bossert TJ, Beauvais JC. Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: a comparative analysis of decision space. Health Policy and Planning. 2002;17(1):14–31. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bossert T. Analyzing the decentralization of health systems in developing countries: decision space, innovation and performance. Social science & medicine. 1998;47(10):1513–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith M, Madon S, Anifalaje A, Lazarro-Malecela M, Michael E. Integrated health information systems in Tanzania: experience and challenges. The Electronic journal of information systems in developing countries. 2007;33(0) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mutemwa RI. HMIS and decision-making in Zambia: re-thinking information solutions for district health management in decentralized health systems. Health Policy and Planning. 2006;21(1):40–52. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czj003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lagomarsino G, Garabrant A, Adyas A, Muga R, Otoo N. Moving towards universal health coverage: health insurance reforms in nine developing countries in Africa and Asia. The Lancet. 2012;380(9845):933–943. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sahay S, Walsham G. Scaling of health information systems in India: Challenges and approaches. Information Technology for Development. 2006;12(3):185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Podolny JM, Page KL. Network forms of organization. Annual review of sociology. 1998:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abrams S, Mark G. Network-centricity: hindered by hierarchical anchors. Proceedings of the 2007 ACM symposium on Computer-Human interaction for the management of information technology; 2007. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kolodny H, Liu M, Stynne B, Denis H. New technology and the emerging organizational paradigm. Human Relations. 1996;49(12):1457–1487. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Castells M. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Randall J, Munro I. Institutional logics and contradictions: competing and collaborating logics in a forum of medical and voluntary practitioners. Journal of Change Management. 2010;10(1):23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ribes D, Finholt TA. The long now of technology infrastructure: articulating tensions in development. Journal of the Association for Information Systems. 2009;10(5):375–398. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andersen ES, Dysvik A, Vaagaasar AL. Organizational rationality and project management. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business. 2009;2(4):479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Braa J, Hanseth O, Heywood A, Mohammed W, Shaw V. Developing Health Information Systems in Developing Countries: The Flexible Standards Strategy. Management Information Systems Quarterly, Special Issue on IT and Development. 2007;31:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Piotti B, Chilundo B, Sahay S. An Institutional Perspective on Health Sector Reforms and the Process of Reframing Health Information Systems Case Study From Mozambique. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2006;42(1):91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Braa J, Monteiro E, Sahay S. Networks of action: sustainable health information systems across developing countries. MIS Quarterly. 2004;28(3):337–362. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oliveira-Cruz V, Kurowski C, Mills A. Delivery of priority health services: searching for synergies within the vertical versus horizontal debate. Journal of International Development. 2003;15(1):67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scutchfield FD, Knight EA, Kelly AV, Bhandari MW, Vasilescu IP. Local public health agency capacity and its relationship to public health system performance. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2004;10(3):204–215. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]