Abstract

The homeless drop out of treatment relatively frequently. Also, prevalence rates of personality disorders are much higher in the homeless group than in the general population. We hypothesize that when both variables coexist — homelessness and personality disorders — the possibility of treatment drop out grows. The aim of this study was to analyze the hypotheses, that is, to study how the existence of personality disorders affects the evolution of and permanence in treatment. One sample of homeless people in a therapeutic community (N = 89) was studied. The structured clinical interview for the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR) was administered and participants were asked to complete the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II (MCMI-II). Cluster B personality disorders (antisocial, borderline, and narcissistic) avoided permanence in the treatment process while cluster C disorders, as dependent, favored adhesion to the treatment and improved the prognosis. Knowledge of these personality characteristics should be used to advocate for better services to support homeless people and prevent their dropping out before completing treatment.

Keywords: MCMI-II, abandonment, personality disorder, homeless

Homeless people are considered to be at the maximum level of social exclusion in a modern society. Homeless people make up one of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged social groups, living in the city streets and temporarily at shelters because of a chained, sudden, and traumatic rupture from family, social, and labor ties, and homelessness is associated with a low quality of life and with high physical and mental illness rates.1–7

Treatment drop out generates much concern among the working teams. In the case of the homeless, this occurs systematically. The way and mode in which they tackle their life, their lack of personal resources to face the situation, and their inertia, determines treatment abandonment, with higher levels than in other populations.8–10

Studies on withdrawal from treatment in people under addiction treatment have been done11–16 and these have analyzed the comorbidity between dropping out and personality disorders.17 The reviewed literature concludes that the presence of personality disorders makes the prognosis of the subjects more difficult; the presence of an associated psychopathology itself is a bad prognosis.18–20

A lower prevalence of schizophrenia and bipolar and somatic disorders has been found in homeless people21 than in the general population. However, other mental pathologies, such as depression, alcohol and drug consumption, or personality disorders22 have an important influence on the dropping out from treatment in homeless people.23 Moreover, psychosocial aspects, such as the return of contact with the family or a history of use of services for homeless people, seem to have positive influence on the drop out rate.24,25

The working tools we have for these disorders are not likely to appear in clinical guidelines, as effective or probably effective treatments. Outcomes, despite the different techniques that have been used, are limited. Only the dialectic behavioral therapy (in the case of borderline disorder),26 cognitive analytic therapy27 or the exposure techniques (in the case of avoidant/phobic disorder) have shown some effectiveness.28 These days there is some research, in homeless people, on the use of community assertive treatment, with encouraging outcomes.29,30 With respect to complex, state of the art treatments, there is some agreement that the coexistence of other pathologies or “comorbidities” hinders the optimal resolution and treatment of the problem, and this is also true in the case of the personality disorders.31–33

The first objective of this study was to establish if there is a relation between the personality disorders and the rate of drop out from treatment given the high rates of both factors in the homeless. The second objective was to identify the existence of personality disorders favoring social and labor reintegration in the homeless.

One secondary aim was to add to the discussion about the relative importance establishing the most efficient treatments of personality disorders, as this is what mental health professionals have named as the 21st century challenge — because of the difficulty of approaching the patient, because of the poor pharmacological results, and because of the great treatment abandonment rate, in people with this pathology.34–39 The research was designed as a prospective ex post-facto study following Montero’s and León’s proposal.40

Method

Participants

The sample comprised homeless persons (N = 89) who participated in a reintegration process in a public center in Zaragoza city. All participants were men older than 18 years. They were chosen from 97 people who participated in a reintegration process, based on the following criteria: (a) being homeless; (b) voluntary admission at the center; (c) stay in the center longer than 2 months; and (d) remaining long enough to complete the study.

A minimum of 2 months in the center had been established to get some adherence to the treatment. Evaluation was not done for the individuals who dropped out of treatment before 2 months.41

Assessment measures

The data that were recorded were the following:

— Sociodemographic variables: a semistructured interview was carried out, in which data were collected regarding age, marital status, and education.

— Homelessness-related variables: At the initial interview, data from the history were collected regarding the age of onset as a transient, reasons for that fact, and substances consumed.

— Personality variables: the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II42 was used. This was administered to people with more than 2 months in the center, trying to achieve the most truthful answers. The questionnaire consists of 175 questions, with a true or false structure, which are answered in 25–30 minutes. The results provide ranking on ten basic personality scales (schizoid avoidant/phobic, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, aggressive/sadistic, compulsive, passive/aggressive, and self-defeating); three pathological personality scales (schizotypal, borderline, and paranoid); six moderately severe clinical syndromes (anxiety, somatoform disorder, bipolar disorder, dysthymic disorder, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse); and three high severity clinical syndromes (thought disorder, major depression, and delusional disorder).

Treatment

The treatment for all of the participants was: individual and group cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, and labor instruction courses. The admission at the center was based upon interviews that determined the motivation to undergo a treatment process. The participants performed activities at the center, and labor training was carried out externally at the end of the process. After the admission at the center, the average stay among the ones who completed the treatment was 1 year. The treatment addressed personal aspects, mainly self-help and psychological advice, both individually and in a group. After the end of the process at the center, monitoring was done in an outpatient program, in a halfway house for 6 months, which served as a support for social reintegration.

Procedure

The prior user profile (previous history) was analyzed by a semistructured interview, in which mainly the sociodemographic data and the personal history of homelessness data were collected. The MCMI-II was administered and tabulated by the clinical psychologist of the center. For the purpose of the study, the presence of personality disorder was considered when the score at the base-rate of the MCMI-II was more than 84, according to the most conservative criteria of Wetzler.43

For data processing, the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) program for Windows in its 15.0 version (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used; Unilateral descriptive (maximum, minimum, mean, standard deviation, and/ or frequencies and percentages), and bilateral correlation statistics were performed. The chi square (×2) tests were used for the comparative study, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The mean age was 38.56, with range between 22 and 54 years old (Table 1). It was observed that the 21.3% (N = 19) of the subjects were younger than 30 years, 36.0% (N = 32) were between 30 and 39 years old, 34.8% (N = 31) were between 40 and 49 years old; and 7.9% (N = 7) were older than 50 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic features (N = 89)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean (years) | 38.56 | |

| Rank (years) | 22–54 | |

| <30 years | 19 | 21.3 |

| 30–39 years | 32 | 36.0 |

| 40–49 years | 31 | 34.8 |

| >50 years | 7 | 7.9 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 54 | 60.7 |

| Married | 1 | 1.1 |

| Divorced | 17 | 19.1 |

| Separated | 15 | 16.9 |

| De facto partnership | 2 | 2.2 |

| Education | ||

| No education | 1 | 1.1 |

| School diploma | 30 | 33.7 |

| Obligatory secondary studies | 42 | 47.2 |

| Vocational training | 10 | 11.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 6 | 6.7 |

At the “marital status” section, we observed that 60.7% (N = 54) were single, which did not mean that they had not had previous partners, even, on some occasion, they had non-recognized or without maintenance, biological children. We found that 36.0% of the study subjects had been married, but at the time of treatment, 19.1% (N = 17) were divorced, and 16.9% (N = 15) were separated. Only a 3.3% (N = 3) had a partner at the time of study, and either were married (N = 1) or had a de facto partnership (N = 2). But the main result data was the number of people who had not established a settled relationship with a partner — the 36.0%, one of every three people in the study.

The analyses of the education level revealed a low level of education: 1.1% had not had the minimum schooling; and 33.7% (N = 30) had obtained primary school certificate. A further 47.2% (N = 42) had completed the secondary obligatory education or equivalent, before leaving school, mainly because of their incorporation to the labor market. Just 17.9% had completed studies over the obligatory ones; of these, 11.2% (N = 10) had followed technical professional training, and 6.7% (N = 6) had a secondary school education. No one had reached the university level.

In relation to the age at which they became transient (Table 2), 38.2% started before the age of 20 (N = 34); 32.6 % became transient between 20 and 29 (N = 29); 27% (N = 24) became transient between 30 and 39 and 2.2% (N = 2) were older than 40 years when they went out from home and into the street. The reasons why they went into the street (Table 2) were the following: 27% (N = 24) had addictions and problems with their family of origin, 14.6% (N = 13) reported divorce, 12.4% (N = 11) had labor problems and 9.0% (N = 8) had psychological problems. It was surprising that the family of origin–problems were the main cause of homelessness and showed how early this phenomenon started. One of every four people placed addictions (alcohol, substances, gambling, etc) as their reason for becoming transient. The psychological and labor problems had lower presence as the trigger element for their pathway to the street.

Table 2.

Homelessness variables (N = 89)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning age | ||

| <20 years | 34 | 38.2 |

| 20–29 years | 29 | 32.6 |

| 30–39 years | 24 | 27.0 |

| 40–49 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| Reason for going into the street | ||

| Divorce | 13 | 14.6 |

| Family of origin–problems | 24 | 27.0 |

| Labor | 11 | 12.4 |

| Addictions | 24 | 27.0 |

| Psychological problems | 8 | 9.0 |

| Other | 9 | 10.1 |

Referring to adherence to treatment (Table 3), there were more people achieving reintegration, 62.9% (N = 56), than who abandoned the program, 37% (N = 33). Among those who reintegrated, we could differentiate: (a) labor reintegration (they found a job); (b) familiar reintegration (return with the family); and (c) social reintegration (perception of a financial benefit). Among those who abandoned the program, we differentiated between: (a) expulsion (because of disruptive behavior with themselves, with others, or with the team or the center); (b) voluntary resignation (the person abandons the treatment voluntarily); (c) not getting through the trial period (abandoned before 2 months in the program at the center); and (d) referral (management with other resources that best suited their needs).

Table 3.

Description of adherence to the treatment (N = 89)

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Reintegration | ||

| Familial | 8 | 9.0 |

| Labor | 46 | 51.7 |

| Social | 2 | 2.2 |

| Abandonment | ||

| Not passing the trial period | 2 | 2.2 |

| Voluntary resignation | 21 | 23.6 |

| Expulsion | 5 | 5.6 |

| Referral | 5 | 5.6 |

| Sum | 89 | 100 |

Referring to the results of the MCMI-II42 (Table 4), it was observed that the Antisocial (25.8%, N = 23), Compulsive (22.5%, N = 20), Dependent (20.2%, N = 18), and Schizoid (19.1%, N = 17) disorders were the ones that obtained the highest scores, considering base rate > 84. We highlighted that there were subjects showing high scores in one or more subscales.

Table 4.

MCMI-II scores (N = 89)

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Presence TP

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||||

| Schizoid | 0 | 117 | 59.98 | 26.543 | 17 | 19.1 |

| Avoidant | 2 | 103 | 50.82 | 29.466 | 12 | 13.5 |

| Dependent | 0 | 108 | 55.70 | 29.933 | 18 | 20.2 |

| histrionic | 5 | 100 | 51.66 | 24.518 | 7 | 79 |

| Narcissistic | 0 | 109 | 56.61 | 24.982 | 8 | 9 |

| Antisocial | 0 | 121 | 65.84 | 28.324 | 23 | 25.8 |

| Aggressive | 0 | 120 | 54.64 | 28.161 | 13 | 14.6 |

| Compulsive | 5 | 120 | 65.82 | 26.168 | 20 | 22.5 |

| Passive | 0 | 103 | 41.93 | 27.971 | 8 | 9 |

| Self-defeating | 0 | 109 | 52.28 | 25.259 | 8 | 9 |

| Schizotypal | 5 | 117 | 55.70 | 25.988 | 14 | 15.7 |

| Borderline | 0 | 112 | 45.47 | 27.686 | 8 | 9 |

| Paranoid | 8 | 118 | 62.43 | 22.869 | 12 | 13.5 |

Abbreviations: MCMI-II, Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II; TP, personality disorders; SD, standard deviation.

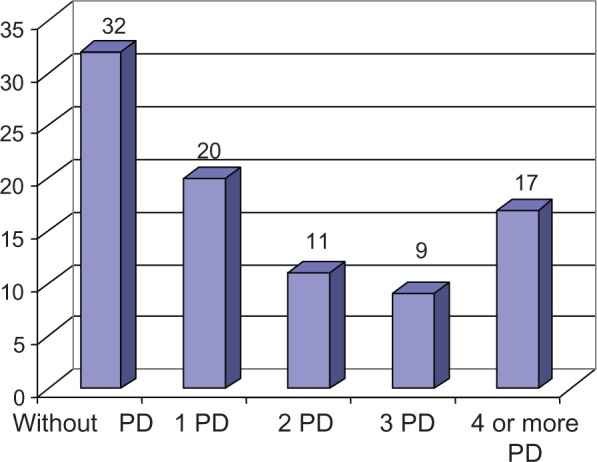

Considering this fact (Figure 1), it was noted that there were subjects in reintegration treatment for the homeless with no personality disorder (36.0% of the cases, N = 32), with one personality disorder (22.5%, N = 20), with two disorders (12.4%; N = 11), with three (10.1%; N = 9), and with four or more personality disorders (19.1%; N = 17).

Figure 1.

Frequency of personality disorders by subject (N = 89).

Abbreviation: PD, personality disorder.

Table 5 shows the means and standard deviations for the different scales of the MCMI-II among the participants who continued or abandoned the treatment process. Among the people who abandoned, higher scores were observed in all the scales, except for the Dependent, Histrionic, and Compulsive, and great differences were highlighted in the Schizoid and Antisocial disorder scales. Nevertheless, only the prognosis for Dependent disorder showed significant difference (P < 0.05).

Table 5.

Comparison of MCMI-II scores according to reintegration and treatment abandonment in the sample

| Personality disorders | Abandonment (N = 33) |

Reintegration (N = 56) |

t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Schizoid | 67.12 | 25.400 | 55.77 | 26.519 | 3.925 |

| Avoidant | 56.21 | 31.012 | 47.64 | 28.317 | 1.772 |

| Dependent | 45.12 | 29.060 | 61.93 | 28.906 | 6.913* |

| Histrionic | 48.21 | 27.418 | 53.70 | 22.651 | 1.039 |

| Narcissistic | 59.30 | 25.656 | 55.02 | 24.671 | 0.608 |

| Antisocial | 72.42 | 26.515 | 61.96 | 28.866 | 2.893 |

| Aggressive | 58.18 | 28.607 | 52.55 | 27.942 | 0.828 |

| Compulsive | 61.76 | 27.830 | 68.21 | 25.085 | 1.268 |

| Passive | 46.85 | 30.046 | 39.04 | 26.524 | 1.632 |

| Self-defeating | 53.33 | 28.805 | 51.66 | 23.173 | 0.090 |

| Schizotypal | 60.88 | 26.408 | 52.64 | 25.480 | 2.112 |

| Borderline | 50.09 | 30.523 | 42.75 | 25.768 | 1.468 |

| Paranoid | 63.21 | 26.609 | 61.96 | 20.597 | 0.061 |

Note: *P < 0.05.

Abbreviation: MCMI-II, Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II.

The prevalence of personality disorders in the homeless is shown in Table 6. Data from other studies with similar samples were compared; they provided data from the general population and from clinical samples.44–46 On the personality limit scale only, the scores of our subjects were below the values of other samples. On the other pathological personality scales, and on the 10 basic scales, the scores obtained by our subjects were higher.

Table 6.

Prevalence of personality disorders in our study and in previous studies

| Personality disorders | General population34 | Echeburúa and Corral (1999)46 | Combaluzier and Pedimielli (2003)45 | Our study (2012) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paranoid | 0.5%–2.5% | 10%–30% | 4.90% | 13.5% |

| Schizoid | 0.5%–4.5% | 1.4%–16% | 4.90% | 19.1% |

| Schizotypal | 3%–5% | 2%–20% | 3.10% | 15.7% |

| Histrionic | 2%–3% | 2%–15% | 3.30% | 7.9% |

| Narcissistic | <1% | 2%–16% | 1.80% | 9.0% |

| Antisocial | 1%–3% | 3%–30% | 18.52% | 25.8% |

| Personality limit | 2%–3% | 10%–40% | 13.21% | 9.0% |

| Avoidant | 0.5%–1% | 10% | 3.20% | 13.5% |

| Dependent | 15% | 2%–22% | 10.41% | 20.2% |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 1% | 3%–10% | 1.10% | 22.5% |

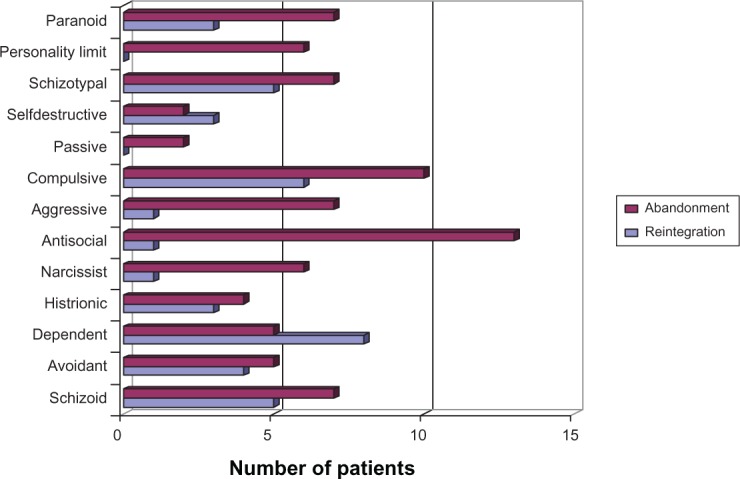

Reintegration and treatment abandonment were compared with respect to the presence of personality disorders (Figure 2). As it can be observed, suffering from an antisocial, aggressive, compulsive or paranoid personality disorder seemed to be related to the treatment abandonment.

Figure 2.

Frequencies of reintegration vs abandonment according to each personality disorder. N = 89.

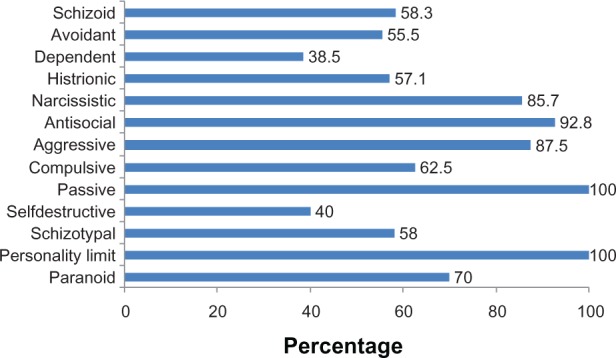

Personality disorders were analyzed in people dropping out of treatment (Figure 3). It was observed that the percentage of abandonment changed in relation to the presence of certain types of personality disorders.

Figure 3.

Percentage of abandonment in persons according to PD. N = 33.

Abbreviation: PD, personality disorder.

Borderline personality disorder or personality limit and passive disorder determined the treatment abandonment in 100% of those patients. Others, such as antisocial personality disorder (92.8%), the aggressive personality disorder (87.5%) and the narcissist personality disorder (85.7%) were poor prognostic factors. On the contrary, the dependent personality disorder and the self destructive (masochistic) disorder, with 38.5% and the 40% respectively, had little specific importance in program abandonment.

Discussion and conclusion

In the study, a high prevalence of personality disorders was observed, well above the epidemiologic data found for the general population.44 Homeless people had great physical deterioration but also and mainly, mental deterioration,47 with pathologies, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder being present.24,35,38,48–51 Likewise, the data corresponds with previous studies with similar characteristics.2,15,23,25,52–54

In the analysis of the sample age, two main facts stand out. On the one hand, the high number of young homeless subjects in the reintegration process; one of every five under study was younger than 30-years-old, which indicated an early beginning in the homelessness phenomenon. On the other hand, the low percentage of persons older than 50 years was surprising — just 7.9%. This could indicate a low interest of this group in the reintegration process due to deterioration suffered during their time on the streets and disenchantment with previous programs.55

In the marital status analysis, the number of people who had not established a settled relationship was remarkable — one of every three. These data were consistent with other studies.56,57

The examination of the relationship between the abandonment of treatment and the personality disorders showed how the personality disorders of the B cluster, also named the dramatic or emotional disorders — antisocial, histrionic, borderline, and narcissistic disorder — presented the worst prognosis.58 This could be due to the presence of interpersonal problems in this group; people with these disorders are defined as poorly socialized subjects, with emotional imbalance and dependency.59–63

The disorders in cluster C: dependent, compulsive, and avoidant personality disorders presented a lower rate of abandonment. Dependent disorder was observed to be a factor for good prognosis because of the high rate of reintegration achieved by the subjects with this disorder.64,65

On the other hand, we could not confirm that the disorders in the cluster A (schizoid, paranoid, and schizotypal) were determinant in the development of the therapeutic process of the person, despite the fact that the abandonment rate in this group was higher than the reintegration rate.

In synthesis, the personality disorders such as borderline, passive, antisocial, aggresive and narcissistic, seemed to have specific importance in the outcomes of treatment processes in homeless people.

People with borderline personality disorder abandoned treatment, in all cases. This could be due to the characteristics of the disorder, which has an irregular pattern of childish reaction and a nonequal development of different abilities, which could increase the chance of showing inconsistent reactions; abandonment could be due to the low thresholds in the neuropsychological and psychochemical systems of these patients, which could also be responsible, in part, for their hyperactivity and their irritability.60,66

Another disorder that was associated with a high abandonment rate was antisocial disorder, which is characterized by a pattern of opposition and resistance attitudes towards the requests in social and labor situations. People with this disorder are irritable and have a low tolerance to frustration, and make continuous claims about their misfortune and contempt for authority figures, which, no doubt, influenced continuance in the reintegration process.67

In the case of narcissistic disorder, abandonment could be related to the disorder characteristics: the arrogant sense of self-worth, the indifference to the welfare of others, and fraudulent and intimidating social ways. Moreover, those with this disorder underestimate others’ rules and opinions, which could make their therapeutic processes difficult.68

Otherwise, we had people with a dependent personality disorder, which seemed to favor remaining in treatment. This personality style, although within the personality styles with interpersonal problems, aims to meet the needs of others; they take a passive position, letting others guide their lives. To protect themselves, dependents are subjugated quickly, hoping to avoid isolation, loneliness, and the horror of abandonment. These circumstances can be increased, in homeless people, by previous experiences.69 These features favored adherence to the treatment processes, where even in the cases of abandonment, participants began, in a short space of time, treatment in other centers.

As a main conclusion and guideline for further research, we could consider the personality disorder suffered by the subject as a prognostic factor in his treatment, so reintegration processes and prevention strategies have to be clearly settled taking the subject’s personality as basic element. Processes should be carried out in a different way, creating an individualized therapeutic process, which should favor a greater rate of reintegration in people who have a previous history of marginalization and years on the street, because the personality disorders in each person seem to determine its prognosis. Our results indicated that standard treatment processes were not followed by some people in the sample, and this possibly could be avoided with more individualized work-directed plans in community assertive treatments,52,70,71 and a new way of organizing homeless services.72,73

As weaknesses of the study, we note that although the MCMI-II is a widely used test in clinical settings, this is considered a self-test,74 so it seems necessary, in future research, to use other, complementary tests that address these circumstances.38 Furthermore, although the multiple diagnostic is an iatrogenic phenomenon linked to all personality disorders and a clear sign of the difficulty of classification in these patients,75,76 the MCMI-II seemed to have a tendency to over diagnose, giving a high incidence of personality disorders,52,77 which could have influenced the results found in this study.

However, this should not limit the usefulness of the MCMI-II in determining the possible presence of personality disorders, and it could be used to plan therapeutic aims and treatments, depending on the personality characteristics of the person.78 Contemplation of new therapeutic directions in work with personality disorders could lead to the achievement of optimized and proper treatment.79,80

Moreover, the size of the sample of homeless persons, although relevant from a clinical point of view, was relatively small from a statistical perspective. Therefore, a greater number of similar studies are required in order to identify the specific profile of personality disorders in homeless people.

Finally, evaluation was not finished in those who dropped out of treatment before 2 months, though it looks as though they can be affected by personality disorders to the same or a greater extent than those who stayed in the process.41 Future research should highlight personality disorders in these patients as well.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Cabrera PJ, Malgesini G, López JA. Un Techo y un Futuro: Buenas Prácticas de Intervención Social con Personas sin Hogar [A roof and a future: best practices for social intervention with homeless] Barcelona: Icaria; 2003. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(2):370–376. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irestig R, Burnström K, Wessel M, Linöe N. How are homeless people treated in the healthcare system and other societal institutions? Study of their experiences and trust. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(3):225–231. doi: 10.1177/1403494809357102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leary MR, Twenge JM, Quinlivan E. Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10(2):111–132. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascual JC, Malagón A, Arcega JM, et al. Utilization of psychiatric emergency services by homeless persons in Spain. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salavera C. Personality disorders in homeless people. Rev Int Psicol Ter Psicol. 2009;9(2):275–283. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Bartels JM. Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(1):56–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrera PJ. La Acción Social con Personas sin Hogar en Espana. [The social action homeless in Spain] Madrid: Cáritas; 2000. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rico P, Vega L, Aranguren L. Trastornos psiquiátricos en transeúntes: un estudio epidemiológico en Aranjuez. [Psychiatric disorders in transients: an epidemiological study in Aranjuez] Rev Asoc Esp Neuropsiquiatr. 1994;14(51):633–649. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salavera C, Tricás JM, Lucha O. Personality disorders and psychosocial problems in a group of participants to therapeutic processes for people with severe social disabilities. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuadrado P. Mejora de la calidad de vida en pacientes con baja adherencia al tratamiento. Intervenciones en dependientes del alcohol “Sin Hogar”. Adicciones. 2003;15(4):321–330. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deane FP, Wootton DJ, Hsu CI, Kelly PJ. Predicting dropout in the first 3 months of 12-step residential drug and alcohol treatment in an Australian sample. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(2):216–225. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domínguez AL, Miranda MD, Pedrero EJ, Pérez M, Puerta C. Estudio de las causas de abandono del tratamiento en un centro de atención a drogodependientes. [Study of the causes of treatment discontinuation in a care facility for drug addicts.] Trastor Adict. 2008;10(2):112–120. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koegel P, Burnam MA. Alcoholism among homeless adults in the inner city of Los Angeles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(11):1011–1018. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navas E, Munoz JJ. Características de personalidad en drogodependencias. [Study of the causes of treatment discontinuation in a care facility for drug addicts] Rev Chil Psicol Clin. 2006;1:51–61. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stecker T, McGovern MP, Herr B. An intervention to increase alcohol treatment engagement: a pilot trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(2):161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fassone G, Ivaldi A, Rocchi MT. Drop-out reduction in patients with severe personality disorders: Preliminary results of an integrated treatment model of group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy. Riv Psichiatr. 2003;38(5):241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salavera C, Puyuelo M, Orejudo S. Trastornos de personalidad y edad: Estudio con personas sin hogar. [Personality disorders and age: Studio homeless] An Psicol. 2009;25(2):261–265. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skodol AE. Personality disorders in DSM 5. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:317–344. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vágnerová MM, Csemy L, Marek J. [Personality characteristics of young homeless.] Psychiatrie. 2012;16(1):8–13. Czech. [Google Scholar]

- 21.North CS, Thompson SJ, Pollio DE, Ricci DA, Smith EM. A diagnostic comparison of homeless and nonhomeless patients in an urban mental health clinic. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(4):236–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00788244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott J. Homelessness and mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:314–324. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conolly AJ, Cobb-Richardson P, Ball SA. Personality disorders in homeless drop-in centre clients. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(6):573–588. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caton CL, Shrout PE, Eagle PF, Opler LA, Felix A, Dominguez B. Risk-factors for homelessness among schizophrenic men — a case control study. Am J Pub Health. 1994;84(2):265–270. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caton CL, Shrout PE, Eagle PF, Opler LA, Felix A. Correlates of codisorders in homeless and never homeless indigent schizophrenic men. Psychol Med. 1994;24(3):681–688. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700027835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linehan MM. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kellet S, Bennett D, Ryle T, Thake A.Cognitive analytic therapy for borderline personality disorder: therapist competence and therapeutic effectiveness in routine practice Clin Psychol PsychoterEpub November232011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hayes C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioural and cognitive therapies. Behav Ther. 2004;35(4):639–665. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coldwell CM, Bender WS. The effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless populations with severe mental illness: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(3):393–399. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fagin L. Management of personality disorders in acute in-patient settings. Part 2: Less-common personality disorders. Adv Psychiatr Treatment. 2004;10:100–106. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feinstein AR. The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease. J Chronic Dis. 1970;23:455–468. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(70)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Donnell C, Cook JM. Cognitive-behavioral therapies for psychological trauma and comorbid substance use disorders. Journal of Chemical Dependence Treatment. 2006;8(2):15–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyrer P. The problem of severity in the classification of personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(3):309–315. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caballo V. Manual para el Tratamiento Cognitivo-Conductual de los Trastornos de Personalidad. [Manual for cognitive-behavioral treatment of personality disorders] Madrid: Siglo XXI; 1998. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller MC. Personality disorders. Med Clin North Am. 2001;85(3):819–837. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gunderson JG, Gabbard GO, editors. Psychotherapy of Personality Disorders Review of Psychiatry. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quiroga E, Errasti JM. Tratamientos psicológicos eficaces para los trastornos de personalidad. [Effective psychological treatments for personality disorders] Psicothema. 2001;13(3):393–406. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubio V, Pérez A. Trastornos de la Personalidad [Personality disorders] Madrid: Elsevier; 2003. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, Trusty ML. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(3):341–348. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montero I, León O. A guide for naming research studies in psychology. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2007;7(3):847–862. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabiner M, Weiner A. Health care for homeless and unstably housed: overcoming barriers. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012;79(5):586–592. doi: 10.1002/msj.21339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Millon T. Spanish . MCMI-II: Inventario Clínico Multiaxial de Millon. 2nd ed. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wetzler S. The Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI): a review. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3):445–464. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loez-Ibor AlinJJ, Valdés Miyar M, American Psychiatric Association . DSM-IV-TR Manual diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales. [Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders] Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2000. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Combaluzier S, Pedinielli JL. Étude de l’impact des troubles mentaux sur les difficultés de réinsertion sociale. [Study of the influence of mental disorders on the problems of social rehabilitation] Ann Med Psychol. 2003;161:31–37. French. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Echeburúa E, Corral P. Avances en el tratamiento cognitivo-conductual de los trastornos de la personalidad. [Advances in cognitive-behavioral treatment of personality disorders] An Modif Cond. 1999;25(102):585–614. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thiesen H, Hesse M. Biological markers of problem drinking in homeless patients. Addic Behav. 2010;35(3):260–262. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ball J, Kearney B, Wilhelm K, Dewhurst-Savellis J, Barton B. Cognitive behaviour therapy and assertion training groups for patients with depression and comorbid personality disorders. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2000;28(1):71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawkins RL, Abrams C. Disappearing acts: the social networks of formerly homeless individuals with co-occurring disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(10):2031–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hayward M, Moran P. Comorbidity of personality disorders and mental illnesses. Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):102–104. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrman H, McGorry P, Bennett P, van Riel R, Singh B. Prevalence of severe mental disorders in disaffiliated and homeless people in inner Melbourne. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(9):1179–1184. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Combaluzier S, Gouvernet B, Bernoussi A. Impact des troubles de la personnalité dans un échantillon de 212 toxicomanes sans domicile fixe [Impact of personality disorders in a sample of 212 homeless drug users] Encephale. 2009;35(5):448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2008.06.009. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salavera C, Puyuelo M, Tricás JM, Lucha O. Comorbilidad de trastornos de personalidad: Estudio en personas sin hogar. [Comorbidity of personality disorders: study homeless] Univ Psychol. 2010;9(2):457–467. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson RG, Hasin D. Psychiatric disorders and treatment among newly homeless young adults with histories of foster care. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(9):906–912. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cabrera PJ. Huéspedes del Aire. Sociología de las Personas sin Hogar en Madrid. [Air guests. sociology of the homeless in Madrid] Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas; 1998. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palepu A, Patterson M, Strehlau V, et al. Daily substance use and mental health symptoms among a cohort of homeless adults in Vancouver, British Columbia J Urban HealthEpub October262012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Munoz M, Vázquez JJ, Panadero S, Vázquez C. Características de las personas sin hogar en Espana: 30 anos de estudios empíricos. [Characteristics of the homeless in Spain: 30 years of empirical studies] Cuad Psiq Com. 2003;3(2):100–116. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Høglend P, Dahl HS, Hersoug AG, Lorentzen S, Perry JC. Long-term effects of transference interpretation in dynamic psychotherapy of personality disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(7):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fagin L. Management of personality disorders in acute in-patient settings. Part 1: Borderline personality disorders. Adv Psychiatr Treatment. 2004;10:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Millon T, Davis RD. Trastornos de la personalidad Más allá del DSM-IV [Personality disorders Beyond DSM-IV] Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 1998. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Millon T, Grossman S, Millon C, Meagher S, Ramnath R. Trastornos de la Personalidad en la Vida Moderna. 2nd ed. Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2006. [Personality disorders in modern life] Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nigg JT, Silk KR, Stavro G, Miller T. Disinhibition and borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17(4):1129–1149. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vazire S, Funder DC. Impulsivity and the self-defeating behavior of narcissists. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2006;10(2):154–165. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rees CS, Anderson RA, Egan SJ. Applying the five-factor model of personality to the exploration of the construct of risk-taking in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2006;34(1):31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nordahl HM, Stiles TC. The specificity of cognitive personality dimensions in Cluster C personality disorders. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2000;28(3):235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Solliday-McRoy C, Campbell TC, Melchert TP, Young TJ, Cisler RA. Neuropsychological functioning of homeless men. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(7):471–478. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000131962.30547.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norton K. Management of difficult personality disorder patients. Adv Psychiatric Treatment. 1996;2:202–210. [Google Scholar]

- 68.O’Connell MJ, Kasprow W, Rosenheck RA. Rates and risk factors for homelessness after successful housing in a sample of formerly homeless veterans. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(3):268–275. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Votta E, Manion IG. Factors in the psychological adjustment of homeless adolescent males: the role of coping style. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(7):778–785. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046871.56865.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davidson KM. Cognitive–behavioural therapy for personality disorders. Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dixon L, Weiden P, Torres M, Lehman A. Assertive community treatment and medication compliance in the homeless mentally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(9):1302–1304. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.9.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bateman AW, Tyrer P. Services for personality disorder: organisation for inclusion. Adv Psychiatric Treatm. 2004;10:425–433. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crawford MJ. Services for people with personality disorder. Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):124–128. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aparicio ME, Sánchez MP. Los estilos de personalidad: su medida a través del inventario Millon de estilos de personalidad. [The personality styles: their measure through the Millon Inventory of Personality Styles] An Psicol. 1999;15(2):191–211. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kupfer DJ, Regier DA, First MB. Agenda de Investigación para el DSM-V [Research Agenda for DSM-V] Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2004. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pailhez G, Palomo AL. Multiplicidad diagnóstica en los trastornos de personalidad. [Multiplicity diagnostic personality disorders] Psiquiatr Biol. 2007;14(3):92–97. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zadeh MD, Damavandi AJ. The incidence of personality disorders among substance dependents and non-addicted psychiatric clients. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:781–784. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Othmer SC, Othmer E. DSM-IV-TR: La Entrevista Clínica Tomo 2: El Paciente Difícil [DSM-IV-TR: The clinical interview Volume 2: The difficult patient] Barcelona: Elsevier-Masson; 2003. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parker G, Barrett E. Personality and personality disorder: current issues and directions. Psychol Med. 2000;30(1):1–9. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosenheck R. Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally ill homeless people: the application of research to policy and practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1563–1570. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]