JSH: In July 2011, the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review [pcodr (http://www.pcodr.ca/)] began accepting submissions by pharmaceutical manufacturers and clinician-based tumour groups to have cancer drugs reimbursed by provincial payers in Canada. Doesn’t Canada already have a body reviewing drugs?

MS: At the national level, there is Health Canada (http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/index-eng.php) that determines whether a drug is safe and effective, and there is the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/english/home.asp?x=1) that sets limits on the prices drug manufacturers can charge to ensure that drug prices are not excessive.

JSH: So why introduce an additional hurdle like pcodr, potentially creating additional delay in getting patients access to the cancer drugs they need?

MS: There are crucial issues that are not addressed until they are reviewed by pcodr—issues that are important not only to physicians but also to people living with cancer and their families as well.

JSH: Like what?

MS: For example, whether a new cancer drug works better than usual care and whether the extra cost seems reasonable.

JSH: So is this why pcodr was established?

MS: The capacity to review both the clinical and economic evidence is limited in Canada. It makes sense to pool resources to provide a national process to review the evidence for new cancer drugs. All Canadians should be able to benefit from the best expertise in the country.

JSH: There is some variation throughout Canada about which oncology drugs are standard care and whether a new drug would constitute a reasonable expenditure. How did pcodr get the provinces to work together in these areas?

MS: In 2007, many of Canada’s provinces participated in the interim Joint Oncology Drug Review. The Review provided evidence-based recommendations for cancer treatments and demonstrated the value that a national collaborative platform can provide to cancer care decision-making. pcodr succeeded the interim Joint Oncology Drug Review and includes the provinces and territories (with the exception of Quebec). In addition, pcodr partners with the provincial cancer agencies, the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health.

JSH: I am concerned about the delay that the pcodr review introduces before patients can access new treatments.

MS: Most cancer-drug budgets are increasing in the double digits, and governments are scrutinizing all new expenditures. If a province or cancer agency doesn’t have access to high-quality information to guide their funding decisions, this can also lead to delays in patient access. Before setting up pcodr, we heard from patients that pcodr needs to be timely in its work. We have tried to reduce the time it takes to review thoroughly the most relevant evidence.

JSH: How?

MS: One way is to allow drug companies to make submissions to pcodrbefore Health Canada has approved their products for sale in Canada. In addition, we focus on transparency. The reasoning behind our recommendations is publically available, which reduces duplication and delay, since the same ground does not need to be covered. All payers have access to the same evidence, which has been reviewed by experts to inform a funding decision.

JSH: So pcodr decides which cancer drugs Canada will pay for?

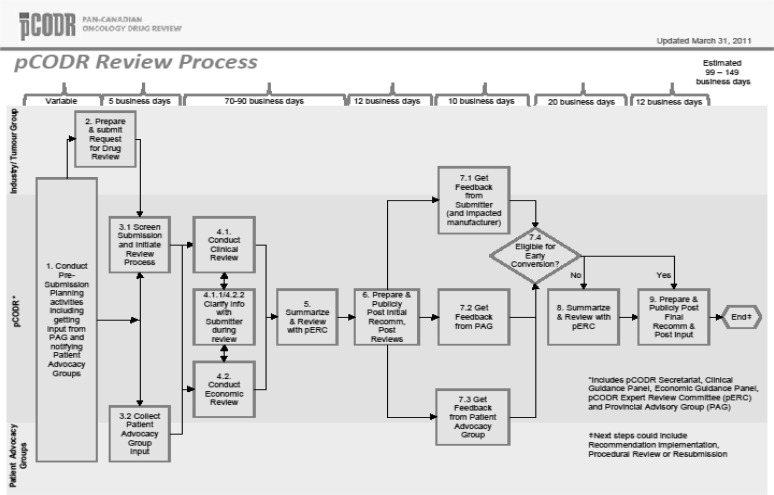

MS: No. pcodr assesses cancer drugs and makes recommendations to the provinces and territories to guide their drug funding decisions (using the process detailed in Figure 1). Most health care funding, including for cancer drugs, is a provincial responsibility. pcodr provides a recommendation based on clinical and economic evidence and patient perspectives; payers such as the provincial ministries of health make their own decisions, based on their own context and budget.

FIGURE 1.

The pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pcodr) Process

JSH: So, it is possible for pcodr to recommend not paying for a drug, but one province might decide to pay for it, and another province might not?

MS: Yes, that could happen. But it may be less likely to happen with the introduction of pcodr, because all provinces are getting the same evidence, and that evidence is reviewed in a high-quality, timely manner.

JSH: Do situations in which provinces don’t follow pcodr’s recommendation represent failure?

MS: No. The provinces designed the pcodr process to help inform them rather than to make decisions. As such, the provinces are a fundamental part of the pcodr process, providing input about how their pcodr can best work for them.

JSH: In other words, the objective of the pcodr process is not to make decisions for health care payers, but instead to gather, evaluate, and summarize the best available clinical and economic evidence?

MS: Right. Based on the evidence review, the pcodr Expert Review Committee (perc) can 1) recommend funding, 2) recommend not funding, or 3) recommend payers consider only if certain conditions are met. Many of perc’s recommendations are from the third category, requiring other factors to be considered by the provinces in their decision-making calculus.

JSH: How do factors other than clinical and economic evidence enter into the pcodr process?

MS: If you are referring to participation by patient groups, there are two distinct opportunities for such participation: 3.2 and 7.3 in Figure 1. Patient groups can provide input and provide feedback in a formal manner. We have had 100% of our submissions receive patient advocacy group input, which means that patients do want and appreciate having a voice in the review process.

JSH: Does anyone pay attention to it?

MS: They have to pay attention to it! For example, perc’s deliberations are based on a deliberative framework that includes 1) clinical benefit, 2) economic evaluation, 3) adoption feasibility, and 4) patient-based values. Reasons for all recommendations must include consideration of 1 through 4. Patient-based values are an important component and can tip the scale.

JSH: Sure, but is it evident whether perc actually considered patient-based values in their deliberations?

MS: Yes ...

JSH: How?

MS: If you go to the pcodr Web site, the status of every review currently under way is posted—from initial meeting to final review. When we complete an official document, that document is posted. We also post the rationale behind every recommendation, including a written discussion specifically about how patient values were considered.

JSH: You post the evidence that was used to support the drug?

MS: Yes.

JSH: And critiques of it?

MS: Yes, and the critiques of the Clinical Guidance Panel and the Economics Guidance Panel and summaries of information submitted by the Provincial Advisory Group and the Patient Advocacy Groups.

JSH: But not the recommendation by perc.

MS: Yes, we post the initial recommendation by perc, with the feedback on it from the submitter, the Provincial Advisory Group, and the Patient Advocacy Groups. At the conclusion of the process, we post publicly the final recommendation from perc.

JSH: It seems as if patient input and transparency are hardwired into the process.

MS: Yes. We think it is important for anyone looking at our recommendations to be able to understand what perc looked at when they made a recommendation, and so the process is designed purposefully to clarify the evidence and other factors we considered.

JSH: What if a patient advocacy group or a manufacturer disagrees with pcodr’s recommendation?

MS: As I mentioned earlier, there is an opportunity to express opinions or to bring forward additional information in the “feedback” stage. Also, it is possible for the manufacturer to make a resubmission with new evidence—for example, perhaps the results of a new trial became available.

JSH: In Canada, non-cancer drugs have their own review process. Why do cancer drugs need a separate process of their own?

MS: Cancer has a strong political dimension to it, and decisions about which drugs to fund can be quite politically and emotionally charged. Cancer therapeutics have also become incredibly complex in the past five years, requiring that highly specialized expertise be actively involved in any review process. Canadian decision-makers set up a separate review process dedicated to cancer. A new process allowed for trying new things.

JSH: Like what?

MS: pcodr is able to support an infrastructure in which clinical experts throughout Canada come together in disease site teams to review the evidence in their area. In this way, disease-specific evidence is reviewed by experts—for example, breast cancer oncologists review the breast cancer evidence. Not only does this leverage the expertise in the country, but it also creates buy-in among clinicians and patients knowing that the right expertise has been actively involved. The pooling of expertise is especially important in health economics, where these skill sets are dismally scarce in Canada.

JSH: If oncologists are reviewing drugs that affect their own specialty, doesn’t that mean they will always recommend every drug?

MS: The clinical reviewers of a drug on the Clinical Guidance Panel are responsible for evaluating the evidence, not deciding whether the drug represents a good use of public funds. perc then takes the clinical and economics guidance panels’ reports into consideration during their deliberation.

JSH: But still, it is hard to say no to something that is state-of-the-art in other countries.

MS: In general, I believe that Canadian physicians are well placed to lead initiatives that prioritize spending our scarce resources in ways that have the most benefit. Rather than make implicit decisions on treatment depending on who is paying for a treatment, I believe Canadians generally value that these decisions be done transparently. Even in the United States, high profile oncologists such as Bach1 and Fojo and Grady2 are urging their colleagues to recognize the need to take the lead in helping to guide health care spending in a responsible way. The very influential American Society of Clinical Oncology has a position statement about the rising costs of cancer care, which says that “communication with patients about the cost of care is a key component of high-quality care”3.

JSH: Who is on perc?

MS: The perc membership includes oncologists, pharmacists, people with health economics experience, and cancer patient and caregiver members.

JSH: So physicians are not solely making the funding decisions?

MS: Ultimately, the decision about treatment is one that is made between a patient and a physician; however, the decision about whether public funds should be used to pay for expensive treatments is based upon clinical and economic evidence, as well as broader values.

JSH: I guess because the drugs pcodr considers have all been approved by Health Canada, it is possible for patients to pay out of pocket if their treatment is not covered by private insurance or by the public drug program.

MS: Yes, but often drug prices are too high for patients to afford a potential treatment option. And sometimes drug prices are too high for public payers to afford them also.

JSH: I see: The money the Ministry of Health doesn’t spend on one drug can be used to provide more care by funding another treatment. This could lead to cases where public payers may not cover a cancer drug that might work (and might be standard of care in the United States), right?

MS: It’s important to separate out how new a treatment is from whether the treatment is better at improving either length of life or quality of life for cancer patients. I think public payers feel that they must be accountable for the public dollars they spend, and this is really how they can demonstrate that value. Beyond the issue of accountability is sustainability. Researchers at the National Cancer Institute in the United States have calculated that it would cost nearly $440 billion ...

JSH: 440 Billion dollars?! That can’t be true ...

MS: ... Yes. They wrote “We would need $440 billion annually—an amount nearly 100 times the budget of the National Cancer Institute—to extend by 1 year the life of the 550,000 Americans who die of cancer annually. And no one would be cured”2. No health care system in the world can afford this.

JSH: How will pcodr help?

MS: By using experts to review the best clinical and economic evidence and clearly stating pcodr’s recommendations and the reasons for them in a transparent way, pcodr can help to inform difficult decisions in a manner that is both in line with scientific evidence and societal values.

JSH: So, by working together in a pan-Canadian effort to obtain and evaluate the evidence, pcodr makes it easier for decision-makers to make difficult, evidence-informed decisions.

MS: Exactly.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Funding in support of this publication was provided by Cancer Care Ontario; however, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Cancer Care Ontario.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach PB. Limits on Medicare’s ability to control rising spending on cancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:626–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0807774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fojo T, Grady C. How much is life worth: cetuximab, non-small cell lung cancer, and the $440 billion question. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1044–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. on behalf of the American Society of Clinical Oncology American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]